|

Santa Catarina (ship)

''Santa Catarina'' was a Portuguese merchant ship, a 1500-ton carrack, that was seized by the Dutch East India Company (also known as V.O.C) during February 1603 off Singapore. She was such a rich prize that her sale proceeds increased the capital of the V.O.C by more than 50%. From the large amounts of Ming Chinese porcelain captured in this ship, Chinese pottery became known in Holland as '' Kraakporselein'', or "carrack-porcelain" for many years. The capture of ''Santa Catarina'' At dawn of 25 February 1603 three Dutch ships under the command of Admiral Jacob van Heemskerck spotted the carrack at anchor off the Eastern coast of Singapore. The Portuguese ship, captained by Sebastian Serrão, was travelling from Macau to Malacca, loaded with products from China and Japan, including 1200 bales of Chinese raw silk, worth 2.2 million guilders. The cargo was particularly valuable because it contained several hundred ounces of musk. After a couple of hours of fighting, the Dutch man ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Carrack

A carrack (; ; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal. Evolved from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for European trade from the Mediterranean to the Baltic and quickly found use with the newly found wealth of the trade between Europe and Africa and then the trans-Atlantic trade with the Americas. In their most advanced forms, they were used by the Portuguese for trade between Europe and Asia starting in the late 15th century, before eventually being superseded in the 17th century by the galleon, introduced in the 16th century. In its most developed form, the carrack was a carvel-built ocean-going ship: large enough to be stable in heavy seas, and capacious enough to carry a large cargo and the provisions needed for very long voyages. The later carracks were square-rigged on the foremast and mainmast and lateen- rigged on the mizzenmast. They had a high roun ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, taxation, and the rights and privileges of the nobility and cities. After the initial stages, Philip II of Spain, the sovereign of the Netherlands, deployed his armies and regained control over most of the rebel-held territories. However, widespread mutinies in the Spanish army caused a general uprising. Under the leadership of the exiled William the Silent, the Catholic- and Protestant-dominated provinces sought to establish religious peace while jointly opposing the king's regime with the Pacification of Ghent, but the general rebellion failed to sustain itself. Despite Governor of Spanish Netherlands and General for Spain, the Duke of Parma's steady military and diplomatic successes, the Union of Utrecht ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Monopoly

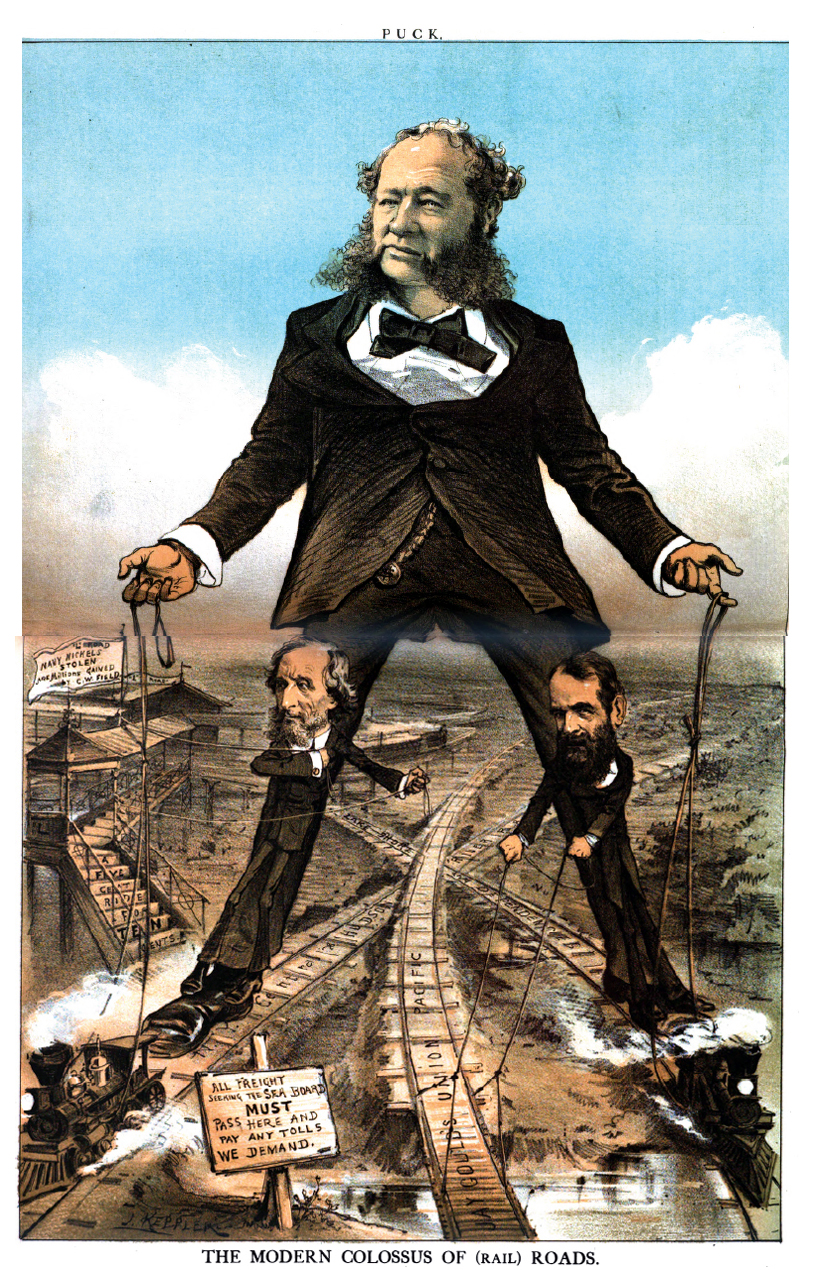

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a specific person or company, enterprise is the only supplier of a particular thing. This contrasts with a monopsony which relates to a single entity's control of a Market (economics), market to purchase a good or service, and with oligopoly and duopoly which consists of a few sellers dominating a market. Monopolies are thus characterized by a lack of economic Competition (economics), competition to produce the good (economics), good or Service (economics), service, a lack of viable substitute goods, and the possibility of a high monopoly price well above the seller's marginal cost that leads to a high monopoly profit. The verb ''monopolise'' or ''monopolize'' refers to the ''process'' by which a company gains the ability to raise ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Free Seas

Freedom of the seas ( la, mare liberum, lit. "free sea") is a principle in the law of the sea. It stresses freedom to navigate the oceans. It also disapproves of war fought in water. The freedom is to be breached only in a necessary international agreement. This principle was one of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points proposed during the First World War. In his speech to the Congress, the president said: The United States' allies Britain and France were opposed to this point, as the United Kingdom was also a considerable naval power at the time. As with Wilson's other points, freedom of the seas was rejected by the German government. Today, the concept of "freedom of the seas" can be found in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea under Article 87(1) which states: "the high seas are open to all states, whether coastal or land-locked". Article 87(1) (a) to (f) gives a non-exhaustive list of freedoms including navigation, overflight, the layin ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mare Clausum

''Mare clausum'' (legal Latin meaning "closed sea") is a term used in international law to mention a sea, ocean or other navigable body of water under the jurisdiction of a state that is closed or not accessible to other states. ''Mare clausum'' is an exception to ''mare liberum'' (Latin for "free sea"), meaning a sea that is open to navigation to ships of all nations. In the generally accepted principle of international waters, oceans, seas, and waters outside national jurisdiction are open to navigation by all and referred to as "high seas" or ''mare liberum''. Portugal and Spain defended a ''Mare clausum'' policy during the age of discovery. This was soon challenged by other European nations. History From 30 BC to 117 AD the Roman Empire came to surround the Mediterranean by controlling most of its coasts. Romans started then to name this sea ''mare nostrum'' (Latin for "our sea"). At those times the period between November and March was considered the most dangerous for na ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

School Of Salamanca

The School of Salamanca ( es, Escuela de Salamanca) is the Renaissance of thought in diverse intellectual areas by Spanish theologians, rooted in the intellectual and pedagogical work of Francisco de Vitoria. From the beginning of the 16th century the traditional Catholic conception of man and of his relation to God and to the world had been assaulted by the rise of humanism, by the Protestant Reformation and by the new geographical discoveries and their consequences. These new problems were addressed by the School of Salamanca. The name refers to the University of Salamanca, where de Vitoria and other members of the school were based. The juridical doctrine of the School of Salamanca represented the end of medieval concepts of law, with a revindication of liberty not habitual in Europe of that time. The natural rights of man came to be, in one form or another, the center of attention, including rights as a corporeal being (right to life, economic rights such as the right to o ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fernando Vázquez De Menchaca

Fernando Vázquez de Menchaca (1512–1569) was a Spanish jurist. Fernando Vázquez de Menchaca was probably born in 1512 in Valladolid. His family members included judges and administrators. He studied law at the universities of Vallodolid and Salamanca, graduating from the latter about 1548. Menchaca held various positions as a judge and bureaucrat, including at the court of Philip II of Spain. Menchaca was a member of the Council of the Indies and the Order of Santiago. He died in 1569 in Seville. He was a hidalgo. In his treatise ''Controversiarum illustrium aliarumque usu frequentium libri tres'' (''Three books of famous and other controversies frequently occurring in practice''), likely first published in Venice in 1564, Menchaca argued that political authority derives from the consent of the governed. Because people form societies by "natural inclination", according to Menchaca, political authority is an aspect of natural law. Menchaca held that persons have natural ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Francisco De Vitoria

Francisco de Vitoria ( – 12 August 1546; also known as Francisco de Victoria) was a Spanish Roman Catholic philosophy, philosopher, theology, theologian, and jurist of Renaissance Spain. He is the founder of the tradition in philosophy known as the School of Salamanca, noted especially for his concept of just war and international law. He has in the past been described by scholars as the "father of international law", along with Alberico Gentili and Hugo Grotius, though some contemporary academics have suggested that such a description is anachronistic, since the concept of postmodern international law did not truly develop until much later. American jurist Arthur Nussbaum noted Vitoria's influence on international law as it pertained to the right to trade overseas. Later this was interpreted as "freedom of commerce". Life Vitoria was born in Burgos or Vitoria-Gasteiz and was raised in Burgos, the son of Pedro de Vitoria, of Alava, and Catalina de Compludo, both of noble fami ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mare Liberum

''Mare Liberum'' (or ''The Freedom of the Seas'') is a book in Latin on international law written by the Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, first published in 1609. In ''The Free Sea'', Grotius formulated the new principle that the sea was international territory and all nations were free to use it for seafaring trade. The disputation was directed towards the Portuguese Mare clausum policy and their claim of monopoly on the East Indian Trade. Grotius wrote the treatise while being a counsel to the Dutch East India Company over the seizing of the Santa Catarina Portuguese carrack issue. The work was assigned to Grotius by the Zeeland Chamber of the Dutch East India Company in 1608. Grotius' argument was that the sea was free to all, and that nobody had the right to deny others access to it. In chapter I, he laid out his objective, which was to demonstrate "briefly and clearly that the Dutch ..have the right to sail to the East Indies", and, also, "to engage in tra ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Natural Law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacted laws of a state or society). According to natural law theory (called jusnaturalism), all people have inherent rights, conferred not by act of legislation but by "God, nature, or reason." Natural law theory can also refer to "theories of ethics, theories of politics, theories of civil law, and theories of religious morality." In the Western tradition, it was anticipated by the pre-Socratics, for example in their search for principles that governed the cosmos and human beings. The concept of natural law was documented in ancient Greek philosophy, including Aristotle, and was referred to in ancient Roman philosophy by Cicero. References to it are also to be found in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, and were later expou ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics. A person who writes polemics, or speaks polemically, is called a ''polemicist''. The word derives , . Polemics often concern questions in religion or politics. A polemical style of writing was common in Ancient Greece, as in the writings of the historian Polybius. Polemic again became common in medieval and early modern times. Since then, famous polemicists have included satirist Jonathan Swift; Italian physicist and mathematician Galileo; French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher Voltaire; Christian anarchist Leo Tolstoy; socialist philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels; novelist George Orwell; playwright George Bernard Shaw; communist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin; psycholinguist Noam Chomsky; social critics Christ ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

.jpg)