|

Lime-ash Floor

Lime-ash floors were an economic form of floor construction from the 15th century to the 19th century, for upper floors in parts of England where limestone or chalk were easily available. They were strong, flexible, and offered heat insulation, good heat and sound insulation. History Lime-ash is the residue found at the bottom of a wood-fired lime kiln, consisting of waste lime and wood ash. These kilns became common in the early 15th century and continued to be used until newer technology replaced them in the late 19th century. Lime-ash could also be made in coal-fired kilns. In areas where gypsum was common they were known as plaster floors. Lime ash was used on the upper floors of yeomen's houses and in great houses such as Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, where the upper surface would be buffed to a fine finish using a mixture of egg-white, curdled milk and isinglass, fish-gelatine. The underside could be left bare or smoothed with a lime-plaster. Alternatively the floor joist coul ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe by the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south. The country covers five-eighths of the island of Great Britain, which lies in the North Atlantic, and includes over 100 smaller islands, such as the Isles of Scilly and the Isle of Wight. The area now called England was first inhabited by modern humans during the Upper Paleolithic period, but takes its name from the Angles, a Germanic tribe deriving its name from the Anglia peninsula, who settled during the 5th and 6th centuries. England became a unified state in the 10th century and has had a significant cultural and legal impact on the wider world since the Age of Discovery, which began during the 15th century. The English language, the Anglican Church, and Engli ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

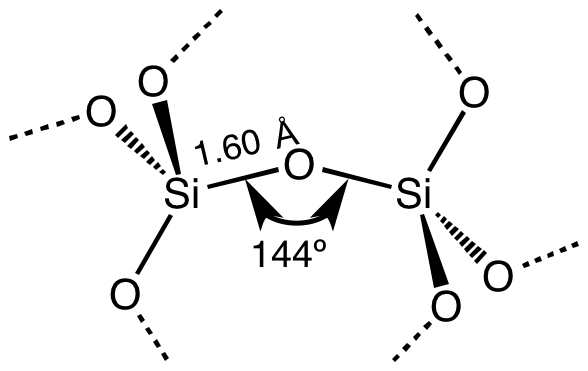

Silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and most abundant families of materials, existing as a compound of several minerals and as a synthetic product. Notable examples include fused quartz, fumed silica, silica gel, opal and aerogels. It is used in structural materials, microelectronics (as an Insulator (electricity), electrical insulator), and as components in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Structure In the majority of silicates, the silicon atom shows tetrahedral coordination geometry, tetrahedral coordination, with four oxygen atoms surrounding a central Si atomsee 3-D Unit Cell. Thus, SiO2 forms 3-dimensional network solids in which each silicon atom is covalently bonded in a tetrahedral manner to 4 oxygen atoms. In contrast, CO2 is a linear ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

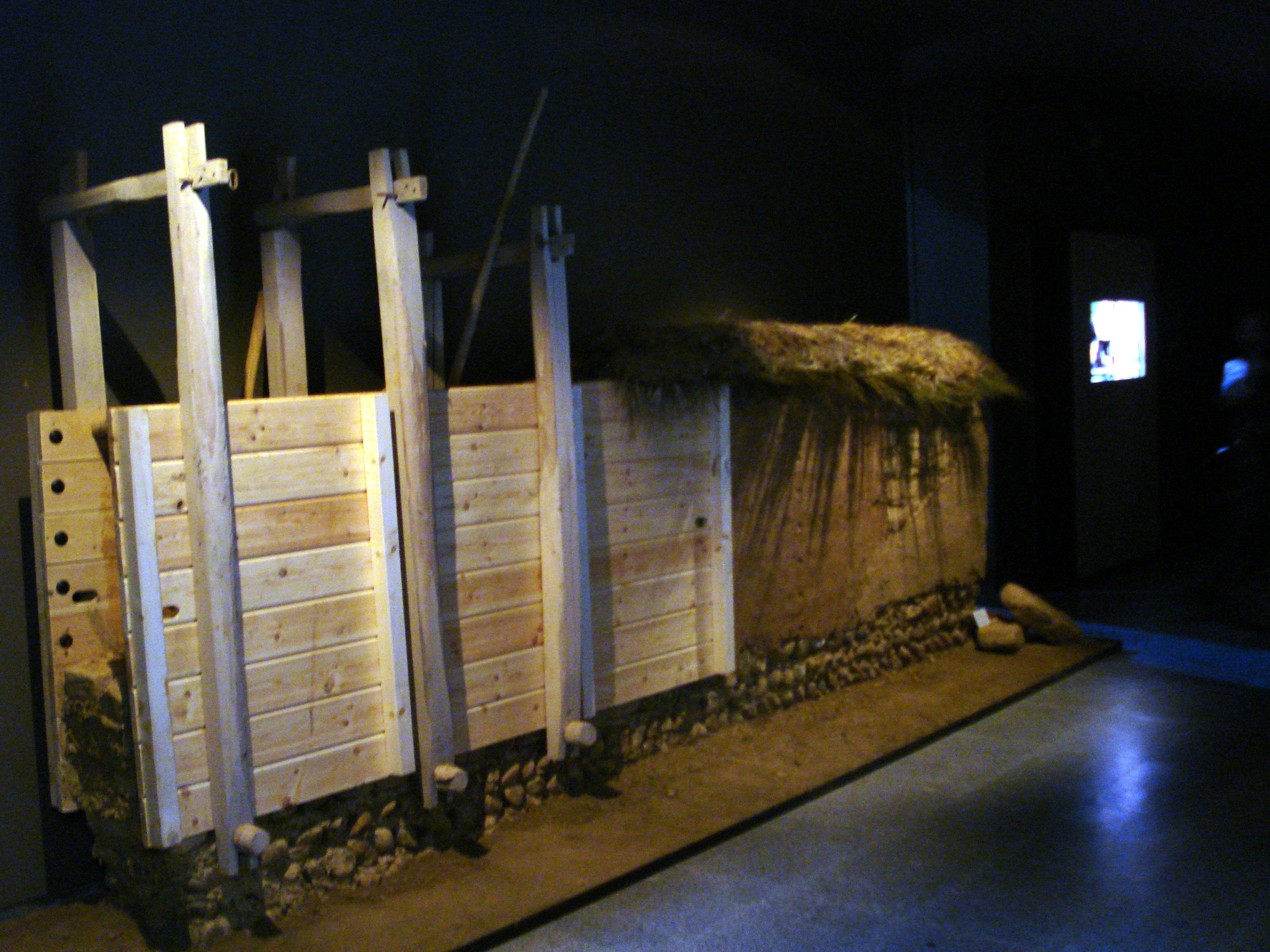

Straw-bale Construction

Straw-bale construction is a building method that uses bales of straw (commonly wheat, rice, rye and oats straw) as structural elements, building insulation, or both. This construction method is commonly used in natural building or "brown" construction projects. Research has shown that straw-bale construction is a sustainable method for building, from the standpoint of both materials and energy needed for heating and cooling. Advantages of straw-bale construction over conventional building systems include the renewable nature of straw, cost, easy availability, naturally fire-retardant and high insulation value. Disadvantages include susceptibility to rot, difficulty of obtaining insurance coverage, and high space requirements for the straw itself. Research has been done using moisture probes placed within the straw wall in which 7 of 8 locations had moisture contents of less than 20%. This is a moisture level that does not aid in the breakdown of the straw. However, proper const ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Rammed Earth

Rammed earth is a technique for constructing foundations, floors, and walls using compacted natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel. It is an ancient method that has been revived recently as a sustainable building method. Under its French name of pisé it is also a material for sculptures, usually small and made in molds. It has been especially used in Central Asia and Tibetan art, and sometimes in China. Edifices formed of rammed earth are on every continent except Antarctica, in a range of environments including temperate, wet, semiarid desert, montane, and tropical regions. The availability of suitable soil and a building design appropriate for local climatic conditions are the factors that favour its use. The French term "pisé de terre" or "terre pisé" was sometimes used in English for architectural uses, especially in the 19th century. The process Making rammed earth involves compacting a damp mixture of subsoil that has suitable proportions ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cob (material)

Cob, cobb, or clom (in Wales) is a natural building material made from subsoil, water, fibrous organic material (typically straw), and sometimes Lime (material), lime. The contents of subsoil vary, and if it does not contain the right mixture, it can be modified with sand or clay. Cob is fireproof, resistant to seismic activity, and uses low-cost materials, although it is very labour intensive. It can be used to create artistic and sculptural forms, and its use has been revived in recent years by the natural building and sustainability movements. In technical building and engineering documents, such as the Uniform Building Code of the western USA, cob may be referred to as "unburned clay masonry," when used in a structural context. It may also be referred to as "aggregate" in non-structural contexts, such as "clay and sand aggregate," or more simply "organic aggregate," such as where cob is a filler between Timber framing, post and beam construction. History and usage ''Cob'' is ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Gainsborough Old Hall

Gainsborough Old Hall in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire is over five hundred years old and one of the best preserved medieval manor houses in England. The hall was built by Sir Thomas Burgh in 1460. The Burghs were rich, flamboyant and powerful. Gainsborough Old Hall was not only their home, but also a demonstration of their wealth and importance. Burgh was a benefactor to Newark Church and also the founder of the Chantry and Alms House at Gainsborough. In 1470, the manor was attacked by Sir Robert Welles over a clash about lands, status, and honour, but it was not severely damaged. In 1484 Thomas entertained King Richard III in his hall. Henry VII intended to raise Thomas to the pre-eminence of a Barony, but no second writ was issued, nor was a patent. In 1510, Thomas Burgh's son, Edward Burgh, 2nd Baron Burgh, was incarcerated at the Old Hall after being declared a lunatic, never having attended the House of Lords. He died in 1528, leaving his eldest son Sir Thomas as head of the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth

Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth (to distinguish it from Woolsthorpe-by-Belvoir in the same county) is a hamlet in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. It is best known as the birthplace of Sir Isaac Newton. Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth is 94 miles (150 km) north of London, northwest of the village of Colsterworth on the A1 one of the UK's primary north–south roads. The A1 is the old Great North Road, on which Colsterworth grew. Woolsthorpe is two to three miles from the county boundary with Leicestershire, and four from Rutland. Woolsthorpe lies in rural surroundings. It sits on Lower Lincolnshire Limestone, below which are the Lower Estuarine Series and the Northampton sand of the Inferior Oolite Series of the Jurassic period. The Northampton Sand here is cemented by iron and in the 20th century the hamlet was almost surrounded by strip mining for iron ore. In 1973 the local quarries closed due to competition from imported iron ore. The same year the G ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Little Morton Hall

Little Moreton Hall, also known as Old Moreton Hall, is a moated half-timbered manor house southwest of Congleton in Cheshire, England. The earliest parts of the house were built for the prosperous Cheshire landowner William Moreton in about 1504–08, and the remainder was constructed in stages by successive generations of the family until about 1610. The building is highly irregular, with three asymmetrical ranges forming a small, rectangular cobbled courtyard. A National Trust guidebook describes Little Moreton Hall as being "lifted straight from a fairy story, a gingerbread house". The house's top-heavy appearance, "like a stranded Noah's Ark", is due to the Long Gallery that runs the length of the south range's upper floor. The house remained in the possession of the Moreton family for almost 450 years, until ownership was transferred to the National Trust in 1938. Little Moreton Hall and its sandstone bridge across the moat are recorded in the National Heritage List for ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Chestnut

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce. The unrelated horse chestnuts (genus ''Aesculus'') are not true chestnuts, but are named for producing nuts of similar appearance that are mildly poisonous to humans. True chestnuts should also not be confused with water chestnuts, which are tubers of an aquatic herbaceous plant in the sedge family Cyperaceae. Other species commonly mistaken for chestnut trees are the chestnut oak ('' Quercus prinus'') and the American beech (''Fagus grandifolia''),Chestnut Tree in chestnuttree.net. both of which are also in the Fagaceae family. |

Winter Wheat

Winter wheat (usually ''Triticum aestivum'') are strains of wheat that are planted in the autumn to germinate and develop into young plants that remain in the vegetative phase during the winter and resume growth in early spring. Classification into spring wheat versus winter wheat is common and traditionally refers to the season during which the crop is grown. For winter wheat, the physiological stage of heading (when the ear first emerges) is delayed until the plant experiences vernalization, a period of 30 to 60 days of cold winter temperatures (0° to 5 °C; 32–41 °F). Winter wheat is usually planted from September to November (in the Northern Hemisphere) and harvested in the summer or early autumn of the next year. In some places (e.g. Chile) a winter-wheat crop fully 'completes' in a year's time before harvest. Winter wheat usually yields more than spring wheat. So-called "facultative" wheat varieties need shorter periods of vernalization time (15–30 days ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Water Reed

Reed is a common name for several tall, grass-like plants of wetlands. Varieties They are all members of the order Poales (in the modern, expanded circumscription), and include: In the grass family, Poaceae * Common reed (''Phragmites australis''), the original species named reed * Giant reed (''Arundo donax''), used for making reeds for musical instruments * Burma reed (''Neyraudia reynaudiana'') * Reed canary-grass (''Phalaris arundinacea'') * Reed sweet-grass (''Glyceria maxima'') * Small-reed (''Calamagrostis'' species) In the sedge family, Cyperaceae * Paper reed or papyrus (''Cyperus papyrus''), the source of the Ancient Egyptian writing material, also used for making boats In the family Typhaceae * Bur-reed (''Sparganium'' species) * Reed-mace (''Typha'' species), also called bulrush or cattail In the family Restionaceae * Cape thatching reed ('' Elegia tectorum''), a restio originating from the South-western Cape, South Africa. * Thatching reed (''Thamnochortus insi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sodium Citrate

Sodium citrate may refer to any of the sodium salts of citric acid (though most commonly the third): * Monosodium citrate * Disodium citrate * Trisodium citrate The three forms of salt are collectively known by the E number E331. Applications Food Sodium citrates are used as acidity regulators in food and drinks, and also as emulsifiers for oils. They enable cheeses to melt without becoming greasy. It reduces the acidity of food as well. Blood clotting inhibitor Sodium citrate is used to prevent donated blood from clotting in storage. It is also used in a laboratory, before an operation, to determine whether a person's blood is too thick and might cause a blood clot, or if the blood is too thin to safely operate. Sodium citrate is used in medical contexts as an alkalinizing agent in place of sodium bicarbonate, to neutralize excess acid in the blood and urine. Metabolic acidosis It has applications for the treatment of metabolic acidosis and chronic kidney disease. Ferr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |