|

Industrial Party Trial

The Industrial Party Trial (November 25 – December 7, 1930) (russian: Процесс Промпартии, Trial of the ''Prompartiya'') was a show trial in which several Soviet scientists and economists were accused and convicted of plotting a coup against the government of the Soviet Union. Nikolai Krylenko, deputy People's Commissar (minister) of Justice, assistant Prosecutor General of the RSFSR and a prominent Bolshevik, prosecuted the case. The presiding judge was Andrey Vyshinsky, later Krylenko's opponent who became notorious as the prosecutor at the Moscow Trials in 1936-1938. The defendants were a group of notable Soviet economists and engineers, including Leonid Ramzin, Peter Osadchy (Пётр Осадчий), Nikolai Charnovsky (Николай Чарновский), Alexander Fedotov (Александр Федотов), Victor Larichev (Виктор Ларичев), Vladimir Ochkin (Владимир Очкин), Ksenofont Sitnin (Ксенофонт Ситнин), ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Industrial Party Trial

The Industrial Party Trial (November 25 – December 7, 1930) (russian: Процесс Промпартии, Trial of the ''Prompartiya'') was a show trial in which several Soviet scientists and economists were accused and convicted of plotting a coup against the government of the Soviet Union. Nikolai Krylenko, deputy People's Commissar (minister) of Justice, assistant Prosecutor General of the RSFSR and a prominent Bolshevik, prosecuted the case. The presiding judge was Andrey Vyshinsky, later Krylenko's opponent who became notorious as the prosecutor at the Moscow Trials in 1936-1938. The defendants were a group of notable Soviet economists and engineers, including Leonid Ramzin, Peter Osadchy (Пётр Осадчий), Nikolai Charnovsky (Николай Чарновский), Alexander Fedotov (Александр Федотов), Victor Larichev (Виктор Ларичев), Vladimir Ochkin (Владимир Очкин), Ksenofont Sitnin (Ксенофонт Ситнин), ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

USSR State Prize

The USSR State Prize (russian: links=no, Государственная премия СССР, Gosudarstvennaya premiya SSSR) was the Soviet Union's state honor. It was established on 9 September 1966. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the prize was followed up by the State Prize of the Russian Federation. The State Stalin Prize ( Государственная Сталинская премия, ''Gosudarstvennaya Stalinskaya premiya''), usually called the Stalin Prize, existed from 1941 to 1954, although some sources give a termination date of 1952. It essentially played the same role; therefore upon the establishment of the USSR State Prize, the diplomas and badges of the recipients of Stalin Prize were changed to that of USSR State Prize. In 1944 and 1945, the last two years of the Second World War, the award ceremonies for the Stalin Prize were not held. Instead, in 1946 the ceremony was held twice: in January for the works created in 1943–1944 and in June for the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

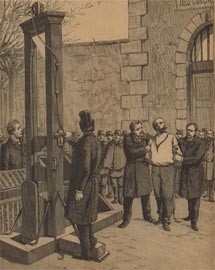

Death Sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that the person is responsible for violating norms that warrant said punishment. The sentence ordering that an offender is to be punished in such a manner is known as a death sentence, and the act of carrying out the sentence is known as an execution. A prisoner who has been sentenced to death and awaits execution is ''condemned'' and is commonly referred to as being "on death row". Crimes that are punishable by death are known as ''capital crimes'', ''capital offences'', or ''capital felonies'', and vary depending on the jurisdiction, but commonly include serious crimes against the person, such as murder, mass murder, aggravated cases of rape (often including child sexual abuse), terrorism, aircraft hijacking, war crimes, crimes against h ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Prompartiya

The Industrial Party Trial (November 25 – December 7, 1930) (russian: Процесс Промпартии, Trial of the ''Prompartiya'') was a show trial in which several Soviet scientists and economists were accused and convicted of plotting a coup against the government of the Soviet Union. Nikolai Krylenko, deputy People's Commissar (minister) of Justice, assistant Prosecutor General of the RSFSR and a prominent Bolshevik, prosecuted the case. The presiding judge was Andrey Vyshinsky, later Krylenko's opponent who became notorious as the prosecutor at the Moscow Trials in 1936-1938. The defendants were a group of notable Soviet economists and engineers, including Leonid Ramzin, Peter Osadchy (Пётр Осадчий), Nikolai Charnovsky (Николай Чарновский), Alexander Fedotov (Александр Федотов), Victor Larichev (Виктор Ларичев), Vladimir Ochkin (Владимир Очкин), Ksenofont Sitnin (Ксенофонт Ситнин), ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pavel Ryabushinsky

Pavel Pavlovich Ryabushinsky (russian: Па́вел Па́влович Рябуши́нский) (17 June 1871, Moscow – 19 July 1924, Cambo-les-Bains), was a Russian entrepreneur and liberal politician. Early life Ryabushinsky was born into the Ryabushinsky dynasty, an Old Believer family that had prospered in the 19th century. His father Mikhail Ryabushinsky was a peasant who moved to Moscow where he adopted the name Ryabushinsky, the name of the settlement where he was born. He was the most successful of Mikhail's three sons. His mother was Evfimia Stepanovna Skvortsova, the daughter of an established Moscow merchant. Like other scions of such merchant families, he had a good education (he spoke French, German, and English) and was anxious both to be accepted into high society and to improve his country. In 1907 he began publishing his own newspaper, '' Utro Rossii'' (The Morning of Russia), to propagate his liberal views. Rebuffed by the Constitutional Democrats, who did ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Shakhty Trial

The Shakhty Trial (russian: Ша́хтинское де́ло) was the first important Soviet show trial since the case of the Socialist Revolutionary Party in 1922. Fifty-three engineers and managers from the North Caucasus town of Shakhty were arrested in 1928 after being accused of conspiring to sabotage the Soviet economy with the former owners of the coal mines. The trial was conducted on May 18, 1928 in House of Trade Unions, Moscow. The Trial In 1928, the local OGPU arrested a group of engineers, including Peter Palchinsky, Nikolai von Meck and A. F. Velichko, in the North Caucasus town of Shakhty, accusing them of conspiring with former owners of coal mines, who were living abroad and barred from the Soviet Union since the Revolution, to sabotage the Soviet economy. The group was charged with a multitude of crimes, including planning the explosions in the mines, buying equipment from foreign companies that was not needed, incorrectly administering labor laws and safety ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Scapegoat

In the Bible, a scapegoat is one of a pair of kid goats that is released into the wilderness, taking with it all sins and impurities, while the other is sacrificed. The concept first appears in the Book of Leviticus, in which a goat is designated to be cast into the desert to carry away the sins of the community. Practices with some similarities to the scapegoat ritual also appear in Ancient Greece and Ebla. Origins Some scholars have argued that the scapegoat ritual can be traced back to Ebla around 2400 BC, from where it spread throughout the ancient Near East. Etymology The word "scapegoat" is an English translation of the Hebrew ( he, עזאזל), which occurs in Leviticus 16:8: The Brown–Driver–Briggs Hebrew Lexicon gives () as a reduplicative intensive of the stem , "remove", hence , "for entire removal". This reading is supported by the Greek Old Testament translation as "the sender away (of sins)". The lexicographer Gesenius takes to mean "averter", wh ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Opportunity Cost

In microeconomic theory, the opportunity cost of a particular activity is the value or benefit given up by engaging in that activity, relative to engaging in an alternative activity. More effective it means if you chose one activity (for example, an investment) you are giving up the opportunity to do a different option. The optimal activity is the one that, net of its opportunity cost, provides the greater return compared to any other activities, net of their opportunity costs. For example, if you buy a car and use it exclusively to transport yourself, you cannot rent it out, whereas if you rent it out you cannot use it to transport yourself. If your cost of transporting yourself without the car is more than what you get for renting out the car, the optimal choice is to use the car yourself. In basic equation form, opportunity cost can be defined as: "Opportunity Cost = (returns on best Forgone Option) - (returns on Chosen Option)." The opportunity cost of mowing one’s own la ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They are sometimes divided into a petty (), middle (), large (), upper (), and ancient () bourgeoisie and collectively designated as "the bourgeoisie". The bourgeoisie in its original sense is intimately linked to the existence of cities, recognized as such by their urban charters (e.g., municipal charters, town privileges, German town law), so there was no bourgeoisie apart from the citizenry of the cities. Rural peasants came under a different legal system. In Marxist philosophy, the bourgeoisie is the social class that came to own the means of production during modern industrialization and whose societal concerns are the value of property and the preservation of capital to ensure the perpetuation of their economic supremacy in society. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the intelligentsia consists of scholars, academics, teachers, journalists, and literary writers. Conceptually, the intelligentsia status class arose in the late 18th century, during the Partitions of Poland (1772–1795). Etymologically, the 19th-century Polish intellectual Bronisław Trentowski coined the term ''inteligencja'' (intellectuals) to identify and describe the university-educated and professionally active social stratum of the patriotic bourgeoisie; men and women whose intellectualism would provide moral and political leadership to Poland in opposing the cultural hegemony of the Russian Empire. In pre–Revolutionary (1917) Russia, the term ''intelligentsiya'' (russian: интеллигенция) identified and described the s ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the country with a newspaper circulation, circulation of 11 million. The newspaper began publication on 5 May 1912 in the Russian Empire, but was already extant abroad in January 1911. It emerged as a leading newspaper of the Soviet Union after the October Revolution. The newspaper was an organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Central Committee of the CPSU between 1912 and 1991. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union ''Pravda'' was sold off by President of Russia, Russian President Boris Yeltsin to a Greek business family in 1996, and the paper came under the control of their private company Pravda International. In 1996, there was an internal dispute between the owners of Pravda International and some of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |