|

Hirudin

Hirudin is a naturally occurring peptide in the salivary glands of blood-sucking leeches (such as ''Hirudo medicinalis'') that has a blood anticoagulant property. This is fundamental for the leeches’ habit of feeding on blood, since it keeps a host's blood flowing after the worm's initial puncture of the skin. Hirudin (MEROPS I14.001) belongs to a superfamily (MEROPS IM) of protease inhibitors that also includes haemadin (MEROPS I14.002) and antistasin (MEROPS I15). Structure During his years in Birmingham and Edinburgh, John Berry Haycraft had been actively engaged in research and published papers on the coagulation of blood, and in 1884, he discovered that the leech secreted a powerful anticoagulant, which he named hirudin, although it was not isolated until the 1950s, nor its structure fully determined until 1976. Full length hirudin is made up of 65 amino acids. These amino acids are organized into a compact N-terminal domain containing three disulfide bonds and a C-termi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Leech

Leeches are segmented parasitic or predatory worms that comprise the subclass Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the oligochaetes, which include the earthworm, and like them have soft, muscular segmented bodies that can lengthen and contract. Both groups are hermaphrodites and have a clitellum, but leeches typically differ from the oligochaetes in having suckers at both ends and in having ring markings that do not correspond with their internal segmentation. The body is muscular and relatively solid, and the coelom, the spacious body cavity found in other annelids, is reduced to small channels. The majority of leeches live in freshwater habitats, while some species can be found in terrestrial or marine environments. The best-known species, such as the medicinal leech, ''Hirudo medicinalis'', are hematophagous, attaching themselves to a host with a sucker and feeding on blood, having first secreted the peptide hirudin to prevent the blood from c ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hirudo Medicinalis

''Hirudo medicinalis'', the European medicinal leech, is one of several species of leeches used as "medicinal leeches". Other species of ''Hirudo'' sometimes also used as medicinal leeches include '' H. orientalis'', ''H. troctina'', and '' H. verbana''. The Asian medicinal leech includes '' Hirudinaria manillensis'', and the North American medicinal leech is '' Macrobdella decora''. Morphology The general morphology of medicinal leeches follows that of most other leeches. Fully mature adults can be up to 20 cm in length, and are green, brown, or greenish-brown with a darker tone on the dorsal side and a lighter ventral side. The dorsal side also has a thin red stripe. These organisms have two suckers, one at each end, called the anterior and posterior suckers. The posterior is used mainly for leverage, whereas the anterior sucker, consisting of the jaw and teeth, is where the feeding takes place. Medicinal leeches have three jaws (tripartite) that resemble saws, on which ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hematophagy

Hematophagy (sometimes spelled haematophagy or hematophagia) is the practice by certain animals of feeding on blood (from the Greek words αἷμα ' "blood" and φαγεῖν ' "to eat"). Since blood is a fluid tissue rich in nutritious proteins and lipids that can be taken without great effort, hematophagy is a preferred form of feeding for many small animals, such as worms and arthropods. Some intestinal nematodes, such as Ancylostomatids, feed on blood extracted from the capillaries of the gut, and about 75 percent of all species of leeches (e.g., ''Hirudo medicinalis'') are hematophagous. The spider Evarcha culicivora feeds indirectly on vertebrate blood by specializing on blood-filled female mosquitoes as their preferred prey. Some fish, such as lampreys and candirus, and mammals, especially the vampire bats, and birds, such as the vampire finches, hood mockingbirds, the Tristan thrush, and oxpeckers also practise hematophagy. Mechanism and evolution These hematophag ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hematophagy

Hematophagy (sometimes spelled haematophagy or hematophagia) is the practice by certain animals of feeding on blood (from the Greek words αἷμα ' "blood" and φαγεῖν ' "to eat"). Since blood is a fluid tissue rich in nutritious proteins and lipids that can be taken without great effort, hematophagy is a preferred form of feeding for many small animals, such as worms and arthropods. Some intestinal nematodes, such as Ancylostomatids, feed on blood extracted from the capillaries of the gut, and about 75 percent of all species of leeches (e.g., ''Hirudo medicinalis'') are hematophagous. The spider Evarcha culicivora feeds indirectly on vertebrate blood by specializing on blood-filled female mosquitoes as their preferred prey. Some fish, such as lampreys and candirus, and mammals, especially the vampire bats, and birds, such as the vampire finches, hood mockingbirds, the Tristan thrush, and oxpeckers also practise hematophagy. Mechanism and evolution These hematophag ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Thrombin

Thrombin (, ''fibrinogenase'', ''thrombase'', ''thrombofort'', ''topical'', ''thrombin-C'', ''tropostasin'', ''activated blood-coagulation factor II'', ''blood-coagulation factor IIa'', ''factor IIa'', ''E thrombin'', ''beta-thrombin'', ''gamma-thrombin'') is a serine protease, an enzyme that, in humans, is encoded by the ''F2'' gene. Prothrombin (coagulation factor II) is proteolytically cleaved to form thrombin in the clotting process. Thrombin in turn acts as a serine protease that converts soluble fibrinogen into insoluble strands of fibrin, as well as catalyzing many other coagulation-related reactions. History After the description of fibrinogen and fibrin, Alexander Schmidt hypothesised the existence of an enzyme that converts fibrinogen into fibrin in 1872. Prothrombin was discovered by Pekelharing in 1894. Physiology Synthesis Thrombin is produced by the enzymatic cleavage of two sites on prothrombin by activated Factor X (Xa). The activity of factor Xa is greatly ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Exosite (biology)

An exosite is a secondary binding site, remote from the active site, on an enzyme or other protein Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo .... This is similar to allosteric sites, but differs in the fact that, in order for an enzyme to be active, its exosite typically must be occupied. Exosites have recently become a topic of increased interest in biomedical research as potential drug targets. References External links * Enzymes Catalysis {{molecular-biology-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

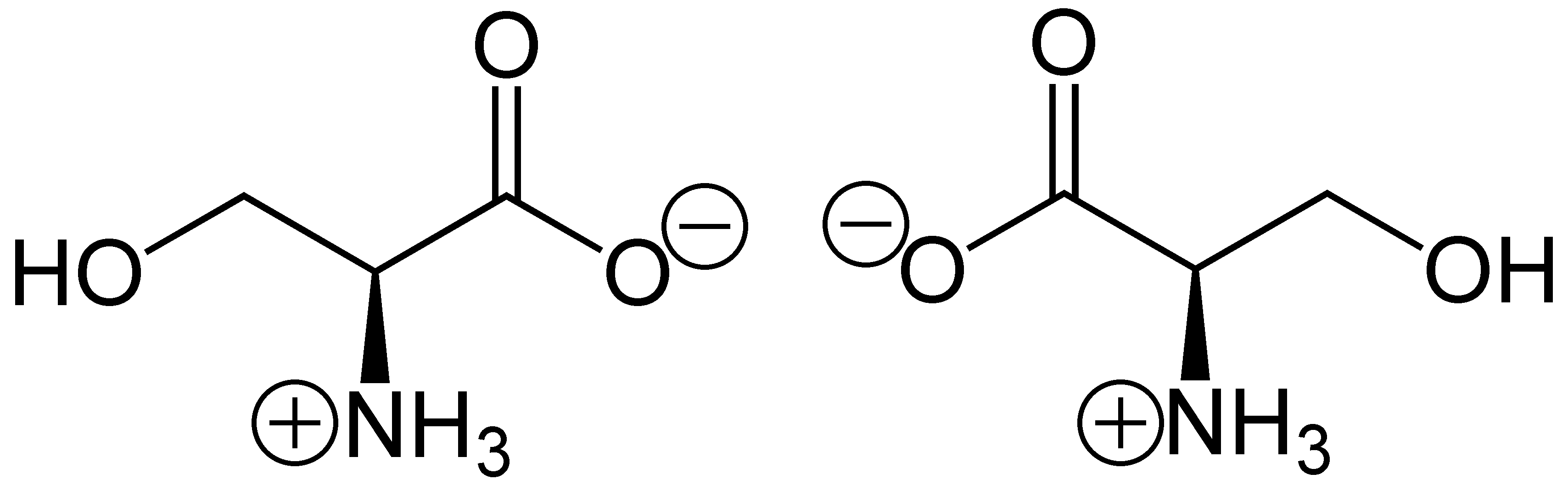

Serine

Serine (symbol Ser or S) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated − form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated − form under biological conditions), and a side chain consisting of a hydroxymethyl group, classifying it as a polar amino acid. It can be synthesized in the human body under normal physiological circumstances, making it a nonessential amino acid. It is encoded by the codons UCU, UCC, UCA, UCG, AGU and AGC. Occurrence This compound is one of the naturally occurring proteinogenic amino acids. Only the L-stereoisomer appears naturally in proteins. It is not essential to the human diet, since it is synthesized in the body from other metabolites, including glycine. Serine was first obtained from silk protein, a particularly rich source, in 1865 by Emil Cramer. Its name is derived from the Latin for silk, ''sericum''. Serine's structure was estab ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Catalytic

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quickly, very small amounts of catalyst often suffice; mixing, surface area, and temperature are important factors in reaction rate. Catalysts generally react with one or more reactants to form intermediates that subsequently give the final reaction product, in the process of regenerating the catalyst. Catalysis may be classified as either homogeneous, whose components are dispersed in the same phase (usually gaseous or liquid) as the reactant, or heterogeneous, whose components are not in the same phase. Enzymes and other biocatalysts are often considered as a third category. Catalysis is ubiquitous in chemical industry of all kinds. Estimates are that 90% of all commercially produced chemical products involve catalysts at some stag ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Electrostatic

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies electric charges at rest (static electricity). Since classical times, it has been known that some materials, such as amber, attract lightweight particles after rubbing. The Greek word for amber, (), was thus the source of the word 'electricity'. Electrostatic phenomena arise from the forces that electric charges exert on each other. Such forces are described by Coulomb's law. Even though electrostatically induced forces seem to be rather weak, some electrostatic forces are relatively large. The force between an electron and a proton, which together make up a hydrogen atom, is about 36 orders of magnitude stronger than the gravitational force acting between them. There are many examples of electrostatic phenomena, from those as simple as the attraction of plastic wrap to one's hand after it is removed from a package, to the apparently spontaneous explosion of grain silos, the damage of electronic components during manufacturi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Anion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convention. The net charge of an ion is not zero because its total number of electrons is unequal to its total number of protons. A cation is a positively charged ion with fewer electrons than protons while an anion is a negatively charged ion with more electrons than protons. Opposite electric charges are pulled towards one another by electrostatic force, so cations and anions attract each other and readily form ionic compounds. Ions consisting of only a single atom are termed atomic or monatomic ions, while two or more atoms form molecular ions or polyatomic ions. In the case of physical ionization in a fluid (gas or liquid), "ion pairs" are created by spontaneous molecule collisions, where each generated pair consists of a free electron and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water. Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thus, prefer other neutral molecules and nonpolar solvents. Because water molecules are polar, hydrophobes do not dissolve well among them. Hydrophobic molecules in water often cluster together, forming micelles. Water on hydrophobic surfaces will exhibit a high contact angle. Examples of hydrophobic molecules include the alkanes, oils, fats, and greasy substances in general. Hydrophobic materials are used for oil removal from water, the management of oil spills, and chemical separation processes to remove non-polar substances from polar compounds. Hydrophobic is often used interchangeably with lipophilic, "fat-loving". However, the two terms are not synonymous. While hydrophobic substances are usually lipophilic, there are exceptions, suc ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Helix

A helix () is a shape like a corkscrew or spiral staircase. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is formed as two intertwined helices, and many proteins have helical substructures, known as alpha helices. The word ''helix'' comes from the Greek word ''ἕλιξ'', "twisted, curved". A "filled-in" helix – for example, a "spiral" (helical) ramp – is a surface called ''helicoid''. Properties and types The ''pitch'' of a helix is the height of one complete helix turn, measured parallel to the axis of the helix. A double helix consists of two (typically congruent) helices with the same axis, differing by a translation along the axis. A circular helix (i.e. one with constant radius) has constant band curvature and constant torsion. A ''conic helix'', also known as a ''conic spiral'', may be defined as a spiral on a conic surface, with the distance to the apex an expo ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |