|

Himantura Walga

''Brevitrygon walga'', the dwarf whipray or mangrove whipray, is a small stingray, a cartilaginous fish in the family Dasyatidae. It is a demersal fish and is found over the continental and insular shelf of the west central Pacific Ocean where it is heavily fished. The IUCN has assessed it as being "near-threatened". Description The dwarf whipray has a maximum length of . The disc width is commonly about . In outline it is oval with a bluntly-pointed snout. The whip-like tail is longer than the body and lacks the skin fold found in some related species. Females have a shorter tail than males, with a bulbous tip, and both sexes have four to six erectile, venomous spines at the base of the tail. The dwarf whipray is a uniform pinkish or beige colour and has been mistaken for a horseshoe crab in turbid water. Distribution and habitat The dwarf whipray is found in the western central Pacific Ocean. Its range extends from Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam to Singapore, Malaysia, the Phi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

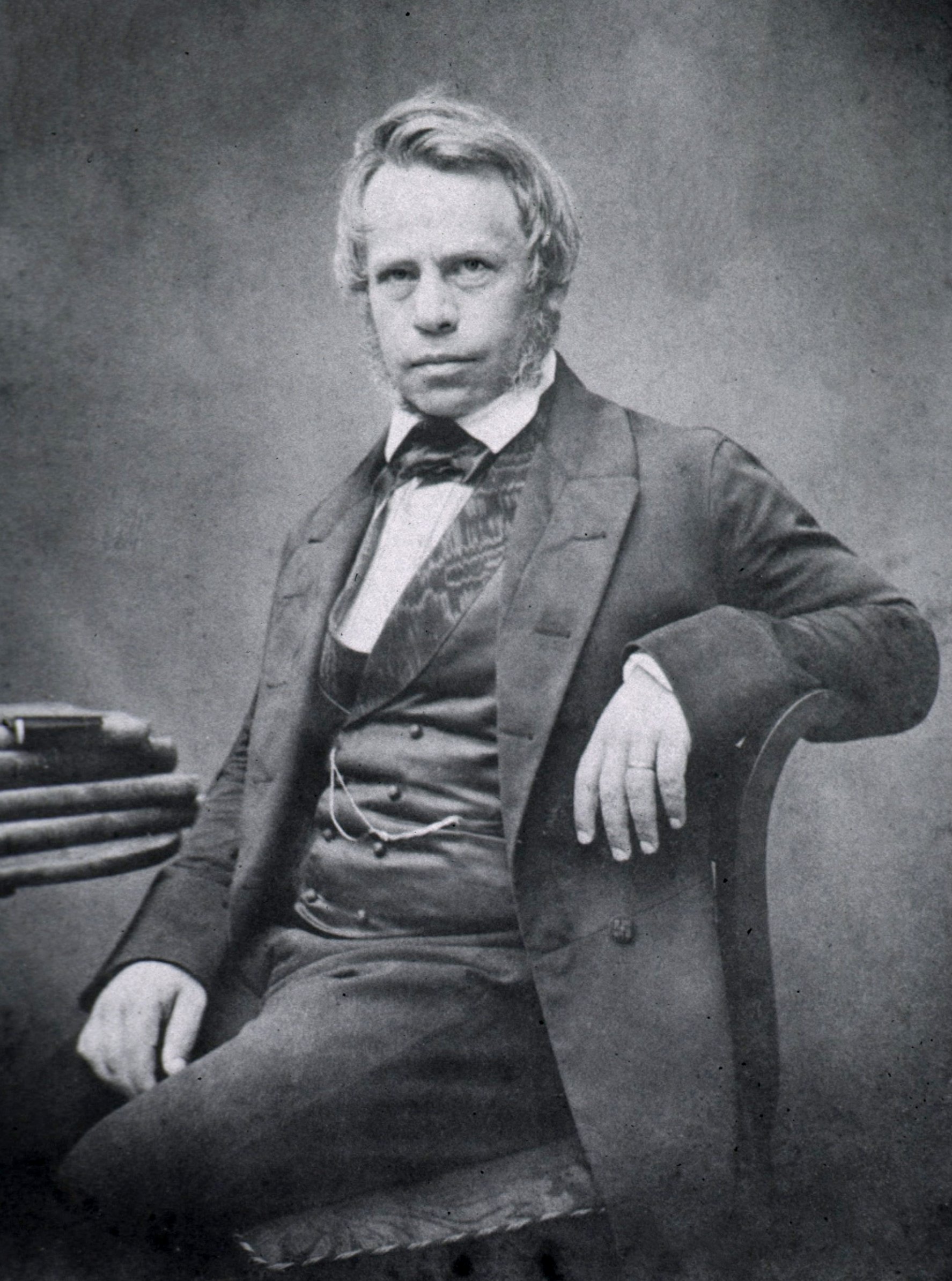

Johannes Peter Müller

Johannes Peter Müller (14 July 1801 – 28 April 1858) was a German physiologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, ichthyology, ichthyologist, and herpetology, herpetologist, known not only for his discoveries but also for his ability to synthesize knowledge. The paramesonephric duct (Müllerian duct) was named in his honor. Life Early years and education Müller was born in Koblenz, Coblenz. He was the son of a poor shoemaker, and was about to be apprenticed to a saddler when his talents attracted the attention of his teacher, and he prepared himself to become a Roman Catholic Priest. During his Secondary school, college course in Koblenz, he devoted himself to the classics and made his own translations of Aristotle. At first, his intention was to become a priest. When he was eighteen, his love for natural science became dominant, and he turned to medicine, entering the University of Bonn in 1819. There he received his Doctor of Medicine, M.D. in 1822. He then studie ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

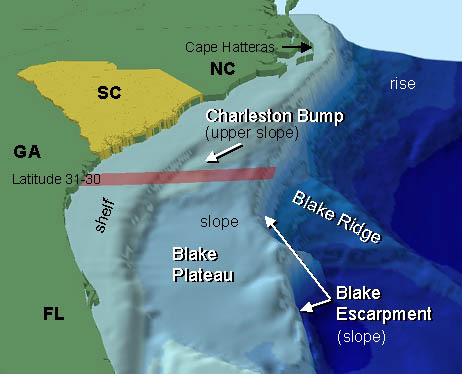

Continental Shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island is known as an ''insular shelf''. The continental margin, between the continental shelf and the abyssal plain, comprises a steep continental slope, surrounded by the flatter continental rise, in which sediment from the continent above cascades down the slope and accumulates as a pile of sediment at the base of the slope. Extending as far as 500 km (310 mi) from the slope, it consists of thick sediments deposited by turbidity currents from the shelf and slope. The continental rise's gradient is intermediate between the gradients of the slope and the shelf. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the name continental shelf was given a legal definition as the stretch of the seabed adjacent to the shores of a par ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fish Of The Indian Ocean

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of living fish species are ray-finned fish, belonging to the class Actinopterygii, with around 99% of those being teleosts. The earliest organisms that can be classified as fish were soft-bodied chordates that first appeared during the Cambrian period. Although they lacked a true spine, they possessed notochords which allowed them to be more agile than their invertebrate counterparts. Fish would continue to evolve through the Paleozoic era, diversifying into a wide variety of forms. Many fish of the Paleozoic developed external armor that protected them from predators. The first fish with jaws appeared in the Silurian period, after which many (such as sharks) became formidable marine predators rather than just the prey of arthropods. Mos ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Brevitrygon

''Brevitrygon'' is a genus of stingrays in the family Dasyatidae from the Indo-Pacific. Its species were formerly contained within the genus ''Himantura''. Species *'' Brevitrygon heterura'' (Bleeker, 1852) *'' Brevitrygon imbricata'' (Bloch & Schneider 1801) (Scaly whipray) *'' Brevitrygon javaensis'' (Last & White, 2013) *'' Brevitrygon walga'' (Müller & Henle Henle can refer to: * Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle, a German physician, pathologist and anatomist (1809–1885) ** Loop of Henle in the kidney, named after Henle *Fritz Henle, a photographer, known as "Mr. Rollei" for his use of the 2.25" square for ..., 1841) (Dwarf whipray) References {{Taxonbar, from=Q26903847 Dasyatidae Taxa named by Bernadette Mabel Manjaji-Matsumoto ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fishing Net

A fishing net is a net used for fishing. Nets are devices made from fibers woven in a grid-like structure. Some fishing nets are also called fish traps, for example fyke nets. Fishing nets are usually meshes formed by knotting a relatively thin thread. Early nets were woven from grasses, flaxes and other fibrous plant material. Later cotton was used. Modern nets are usually made of artificial polyamides like nylon, although nets of organic polyamides such as wool or silk thread were common until recently and are still used. History Fishing nets have been used widely in the past, including by stone age societies. The oldest known fishing net is the net of Antrea, found with other fishing equipment in the Karelian town of Antrea, Finland, in 1913. The net was made from willow, and dates back to 8300 BC. Recently, fishing net sinkers from 27,000 BC were discovered in Korea, making them the oldest fishing implements discovered, to date, in the world. The remnants of another f ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Batoidea

Batoidea is a superorder of cartilaginous fishes, commonly known as rays. They and their close relatives, the sharks, comprise the subclass Elasmobranchii. Rays are the largest group of cartilaginous fishes, with well over 600 species in 26 families. Rays are distinguished by their flattened bodies, enlarged pectoral fins that are fused to the head, and gill slits that are placed on their ventral surfaces. Anatomy Batoids are flat-bodied, and, like sharks, are cartilaginous fish, meaning they have a boneless skeleton made of a tough, elastic cartilage. Most batoids have five ventral slot-like body openings called gill slits that lead from the gills, but the Hexatrygonidae have six. Batoid gill slits lie under the pectoral fins on the underside, whereas a shark's are on the sides of the head. Most batoids have a flat, disk-like body, with the exception of the guitarfishes and sawfishes, while most sharks have a spindle-shaped body. Many species of batoid have developed their pe ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bycatch

Bycatch (or by-catch), in the fishing industry, is a fish or other marine species that is caught unintentionally while fishing for specific species or sizes of wildlife. Bycatch is either the wrong species, the wrong sex, or is undersized or juveniles of the target species. The term "bycatch" is also sometimes used for untargeted catch in other forms of animal harvesting or collecting. Non- marine species (freshwater fish not saltwater fish) that are caught (either intentionally or unintentionally) but regarded as generally "undesirable" are referred to as "rough fish" (mainly US) and " coarse fish" (mainly UK). In 1997, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defined bycatch as "total fishing mortality, excluding that accounted directly by the retained catch of target species". Bycatch contributes to fishery decline and is a mechanism of overfishing for unintentional catch. The average annual bycatch rate of pinnipeds and cetaceans in the US from 199 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Histotrophy

Histotrophy is a form of matrotrophy exhibited by some live-bearing sharks and rays, in which the developing embryo receives additional nutrition from its mother in the form of uterine secretions, known as histotroph (or "uterine milk"). It is one of the three major modes of elasmobranch reproduction encompassed by " aplacental viviparity", and can be contrasted with yolk-sac viviparity (in which the embryo is solely sustained by yolk) and oophagy (in which the embryo feeds on ova). There are two categories of histotrophy: *In mucoid or limited histotrophy, the developing embryo ingests uterine mucus or histotroph as a supplement to the energy supplies provided by its yolk sac. This form of histotrophy is known to occur in the dogfish sharks (Squaliformes) and the electric rays (Torpediniformes), and may be more widespread. *In lipid histotrophy, the developing embryo is supplied with protein and lipid-enriched histotroph through specialized finger-like structures known as trophone ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Gestation Period

In mammals, pregnancy is the period of reproduction during which a female carries one or more live offspring from implantation in the uterus through gestation. It begins when a fertilized zygote implants in the female's uterus, and ends once it leaves the uterus. Fertilization and implantation During copulation, the male inseminates the female. The spermatozoon fertilizes an ovum or various ova in the uterus or fallopian tubes, and this results in one or multiple zygotes. Sometimes, a zygote can be created by humans outside of the animal's body in the artificial process of in-vitro fertilization. After fertilization, the newly formed zygote then begins to divide through mitosis, forming an embryo, which implants in the female's endometrium. At this time, the embryo usually consists of 50 cells. Development After implantation A blastocele is a small cavity on the center of the embryo, and the developing embryonary cells will grow around it. Then, a flat layer cell forms on ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Viviparous

Among animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the parent. This is opposed to oviparity which is a reproductive mode in which females lay developing eggs that complete their development and hatch externally from the mother. The term 'viviparity' and its adjective form 'viviparous' derive from the Latin ''vivus'' meaning "living" and ''pario'' meaning "give birth to". Reproductive mode Five modes of reproduction have been differentiated in animals based on relations between zygote and parents. The five include two nonviviparous modes: ovuliparity, with external fertilisation, and oviparity, with internal fertilisation. In the latter, the female lays zygotes as eggs with a large yolk; this occurs in all birds, most reptiles, and some fishes. These modes are distinguished from viviparity, which covers all the modes that result in live birth: *Histotrophic viviparity: the zygotes develop in the female's oviducts, but find their nutrients by oophagy ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Scaly Whipray

The ''scaly whipray'' or Bengal whipray, (''Brevitrygon imbricata'') is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, found in the tropical Indo-West Pacific oceans from the Red Sea and Mauritius to Indonesia. Its width is up to , and it may reach in total length. The scaly whipray is found in inshore coastal waters, typically in estuarine habitats. Some uncertainty exists over the details of its habitat preference and full range due to confusion with the very similar '' Brevitrygon walga'', and reports from Tonlé Sap ("Great Lake") possibly refer to '' Hemitrygon laosensis''. The disc width of the scaly whipray is equal to its disc length, and the tail is shorter than the body. The ventral surface of the disc is entirely white. Young and adults feed on benthic The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from ancient ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle (; 9 July 1809 – 13 May 1885) was a German physician, pathologist, and anatomist. He is credited with the discovery of the loop of Henle in the kidney. His essay, "On Miasma and Contagia," was an early argument for the germ theory of disease. He was an important figure in the development of modern medicine. Biography Henle was born in Fürth, Bavaria, to Simon and Rachel Diesbach Henle (Hähnlein). He was Jewish. After studying medicine at Heidelberg and at Bonn, where he took his doctor's degree in 1832, he became prosector in anatomy to Johannes Müller at Berlin. During the six years he spent in that position he published a large amount of work, including three anatomical monographs on new species of animals and papers on the structure of the lymphatic system, the distribution of epithelium in the human body, the structure and development of the hair, and the formation of mucus and pus. In 1840, he accepted the chair of anatomy at Zürich an ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

2.jpg)