|

Hexaphenylethane

Hexaphenylethane is a hypothetical organic compound consisting of an ethane core with six phenyl substituents. All attempts at its synthesis have been unsuccessful. The trityl free radical, Ph3C, was originally thought to dimerize to form hexaphenylethane. However, an inspection of the NMR spectrum of this dimer reveals that it is in fact a non-symmetrical species, Gomberg's dimer instead. A substituted derivative of hexaphenylethane, hexakis(3,5-di-''t''-butylphenyl)ethane, has however been prepared. It features a very long central C–C bond at 167 pm (compared to the typical bond length of 154 pm). Attractive London dispersion forces between the ''t''-butyl substituents are believed to be responsible for the stability of this very hindered molecule. See also * Tetraphenylmethane Tetraphenylmethane is an organic compound consisting of a methane core with four phenyl substituents. It was first synthesized by Moses Gomberg in 1898. Synthesis Gomberg's ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Triphenylmethyl Radical

The triphenylmethyl radical (often shorted to trityl radical) is an organic compound with the formula (C6H5)3C. It is a persistent radical. It was the first radical ever to be described in organic chemistry. Because of its accessibility, the trityl radical has been heavily exploited. Preparation and properties It can be prepared by homolysis of triphenylmethyl chloride 1 by a metal like silver or zinc in benzene or diethyl ether. The radical 2 forms a chemical equilibrium with the quinoid-type dimer 3 (Gomberg's dimer). In benzene the concentration of the radical is 2%. Solutions containing the radical are yellow; when the temperature of the solution is raised, the yellow color becomes more intense as the equilibrium is shifted in favor of the radical (in accordance with Le Chatelier's principle). When exposed to air, the radical rapidly oxidizes to the peroxide, and the color of the solution changes from yellow to colorless. Likewise, the radical reacts with iodine to t ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Gomberg's Dimer

Gomberg's dimer is the organic compound with the formula Ph2C=C6H5-CPh3, where Ph = C6H5. It is a yellow solid that is air-stable for hours at room temperature and soluble in organic solvents. The compound achieved fame as the dimer of triphenylmethyl radical, which was prepared by Moses Gomberg in his quest for hexaphenylethane. Its quinoid structure has been determined by X-ray crystallography. The C-C bond that reversibly breaks is rather long at 159.7 picometer The picometre (international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: pm) or picometer ( American spelling) is a unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), equal to , or one trillionth ...s. Synthesis and reactions Gomberg's dimer can be prepared quantitatively by treating trityl bromide with powdered copper or silver: :2Ph3CBr + 2Cu → Ph2C=C6H5-CPh3 + 2CuBr Gomberg's dimer reversibly dissociates to the triphenylmethyl radical in organic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tetraphenylmethane

Tetraphenylmethane is an organic compound consisting of a methane core with four phenyl substituents. It was first synthesized by Moses Gomberg in 1898. Synthesis Gomberg's classical organic synthesis shown below starts by reacting triphenylmethyl bromide 1 with phenylhydrazine 2 to the hydrazine 3. Oxidation with nitrous acid then produces the azo compound 4 from which on heating above the melting point, nitrogen gas evolves with formation of tetraphenylmethane 5.{{cite journal , title = On tetraphenylmethane , first= M. , last=Gomberg , journal = J. Am. Chem. Soc. , year = 1898 , volume = 20 , issue = 10 , pages = 773–780 , doi= 10.1021/ja02072a009, url= https://zenodo.org/record/1428930 : Gomberg was able to distinguish this compound from triphenylmethane ( elemental analysis was not an option given the small differences in the hydrogen fractions of 6.29% and 6.60%) by nitration of 5 with nitric acid to 6. A strong base would be able to abstract th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Organic Compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon- hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The study of the properties, reactions, and syntheses of organic compounds comprise the discipline known as organic chemistry. For historical reasons, a few classes of carbon-containing compounds (e.g., carbonate salts and cyanide salts), along with a few other exceptions (e.g., carbon dioxide, hydrogen cyanide), are not classified as organic compounds and are considered inorganic. Other than those just named, little consensus exists among chemists on precisely which carbon-containing compounds are excluded, making any rigorous definition of an organic compound elusive. Although organic compounds make up only a small percentage of Earth's crust, they are of central importance because all known life is based on organic compounds. Livin ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ethane

Ethane ( , ) is an organic chemical compound with chemical formula . At standard temperature and pressure, ethane is a colorless, odorless gas. Like many hydrocarbons, ethane is isolated on an industrial scale from natural gas and as a petrochemical by-product of petroleum refining. Its chief use is as feedstock for ethylene production. Related compounds may be formed by replacing a hydrogen atom with another functional group; the ethane moiety is called an ethyl group. For example, an ethyl group linked to a hydroxyl group yields ethanol, the alcohol in beverages. History Ethane was first synthesised in 1834 by Michael Faraday, applying electrolysis of a potassium acetate solution. He mistook the hydrocarbon product of this reaction for methane and did not investigate it further. During the period 1847–1849, in an effort to vindicate the radical theory of organic chemistry, Hermann Kolbe and Edward Frankland produced ethane by the reductions of propionitrile ( e ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Phenyl

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic group of atoms with the formula C6 H5, and is often represented by the symbol Ph. Phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as a benzene ring, minus a hydrogen, which may be replaced by some other element or compound to serve as a functional group. Phenyl group has six carbon atoms bonded together in a hexagonal planar ring, five of which are bonded to individual hydrogen atoms, with the remaining carbon bonded to a substituent. Phenyl groups are commonplace in organic chemistry. Although often depicted with alternating double and single bonds, phenyl group is chemically aromatic and has equal bond lengths between carbon atoms in the ring. Nomenclature Usually, a "phenyl group" is synonymous with C6H5− and is represented by the symbol Ph or, archaically, Φ. Benzene is sometimes denoted as PhH. Phenyl groups are generally attached to other atoms or groups. For example, triphenylmethane ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Substituent

A substituent is one or a group of atoms that replaces (one or more) atoms, thereby becoming a moiety in the resultant (new) molecule. (In organic chemistry and biochemistry, the terms ''substituent'' and '' functional group'', as well as '' side chain'' and ''pendant group'', are used almost interchangeably to describe those branches from the parent structure, though certain distinctions are made in polymer chemistry. In polymers, side chains extend from the backbone structure. In proteins, side chains are attached to the alpha carbon atoms of the amino acid backbone.) The suffix ''-yl'' is used when naming organic compounds that contain a single bond replacing one hydrogen; ''-ylidene'' and ''-ylidyne'' are used with double bonds and triple bonds, respectively. In addition, when naming hydrocarbons that contain a substituent, positional numbers are used to indicate which carbon atom the substituent attaches to when such information is needed to distinguish between ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Organic Synthesis

Organic synthesis is a special branch of chemical synthesis and is concerned with the intentional construction of organic compounds. Organic molecules are often more complex than inorganic compounds, and their synthesis has developed into one of the most important branches of organic chemistry. There are several main areas of research within the general area of organic synthesis: '' total synthesis'', '' semisynthesis'', and ''methodology''. Total synthesis A total synthesis is the complete chemical synthesis of complex organic molecules from simple, commercially available petrochemical or natural precursors. Total synthesis may be accomplished either via a linear or convergent approach. In a ''linear'' synthesis—often adequate for simple structures—several steps are performed one after another until the molecule is complete; the chemical compounds made in each step are called synthetic intermediates. Most often, each step in a synthesis refers to a separate ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dimer (chemistry)

A dimer () (''di-'', "two" + ''-mer'', "parts") is an oligomer consisting of two monomers joined by bonds that can be either strong or weak, covalent or intermolecular. Dimers also have significant implications in polymer chemistry, inorganic chemistry, and biochemistry. The term ''homodimer'' is used when the two molecules are identical (e.g. A–A) and ''heterodimer'' when they are not (e.g. A–B). The reverse of dimerization is often called dissociation. When two oppositely charged ions associate into dimers, they are referred to as ''Bjerrum pairs'', after Niels Bjerrum. Noncovalent dimers Anhydrous carboxylic acids form dimers by hydrogen bonding of the acidic hydrogen and the carbonyl oxygen. For example, acetic acid forms a dimer in the gas phase, where the monomer units are held together by hydrogen bonds. Under special conditions, most OH-containing molecules form dimers, e.g. the water dimer. Excimers and exciplexes are excited structures with a short life ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

NMR Spectrum

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, most commonly known as NMR spectroscopy or magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), is a spectroscopic technique to observe local magnetic fields around atomic nuclei. The sample is placed in a magnetic field and the NMR signal is produced by excitation of the nuclei sample with radio waves into nuclear magnetic resonance, which is detected with sensitive radio receivers. The intramolecular magnetic field around an atom in a molecule changes the resonance frequency, thus giving access to details of the electronic structure of a molecule and its individual functional groups. As the fields are unique or highly characteristic to individual compounds, in modern organic chemistry practice, NMR spectroscopy is the definitive method to identify monomolecular organic compounds. The principle of NMR usually involves three sequential steps: # The alignment (polarization) of the magnetic nuclear spins in an applied, constant magnetic field B0. # The p ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

London Dispersion Force

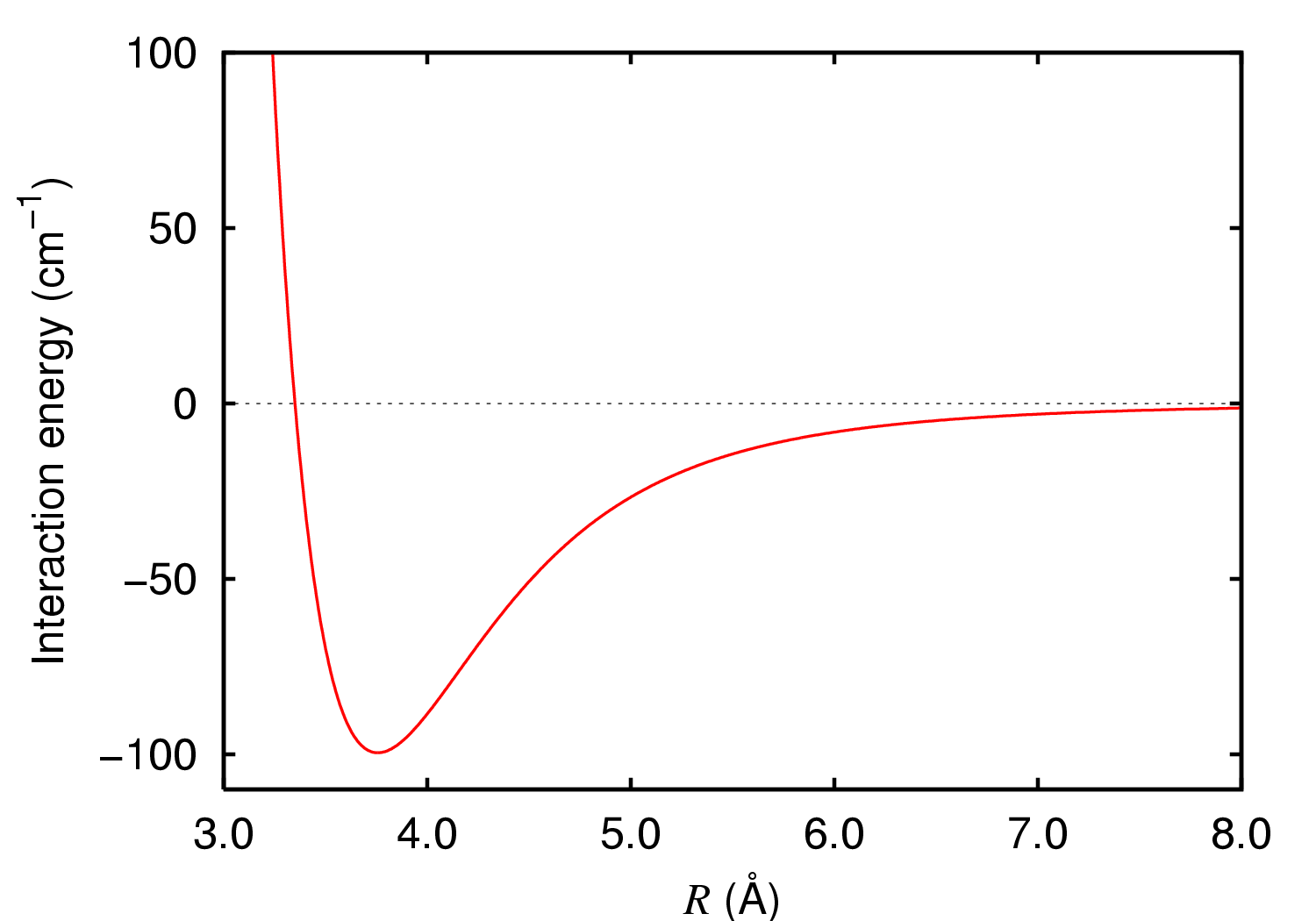

London dispersion forces (LDF, also known as dispersion forces, London forces, instantaneous dipole–induced dipole forces, fluctuating induced dipole bonds or loosely as van der Waals forces) are a type of intermolecular force acting between atoms and molecules that are normally electrically symmetric; that is, the electrons are symmetrically distributed with respect to the nucleus. They are part of the van der Waals forces. The LDF is named after the German physicist Fritz London. They are the weakest intermolecular force. Introduction The electron distribution around an atom or molecule undergoes fluctuations in time. These fluctuations create instantaneous electric fields which are felt by other nearby atoms and molecules, which in turn adjust the spatial distribution of their own electrons. The net effect is that the fluctuations in electron positions in one atom induce a corresponding redistribution of electrons in other atoms, such that the electron motions become corre ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tert-Butyl

In organic chemistry, butyl is a four-carbon alkyl radical or substituent group with general chemical formula , derived from either of the two isomers (''n''-butane and isobutane) of butane. The isomer ''n''-butane can connect in two ways, giving rise to two "-butyl" groups: * If it connects at one of the two terminal carbon atoms, it is normal butyl or ''n''-butyl: (preferred IUPAC name: butyl) * If it connects at one of the non-terminal (internal) carbon atoms, it is secondary butyl or ''sec''-butyl: (preferred IUPAC name: butan-2-yl) The second isomer of butane, isobutane, can also connect in two ways, giving rise to two additional groups: * If it connects at one of the three terminal carbons, it is isobutyl: (preferred IUPAC name: 2-methylpropyl) * If it connects at the central carbon, it is tertiary butyl, ''tert''-butyl or ''t''-butyl: (preferred IUPAC name: ''tert''-butyl) Nomenclature According to IUPAC nomenclature, "isobutyl", "''sec''-butyl", and "''tert'' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |