|

Fugitive Slave Convention

The Fugitive Slave Law Convention was held in Cazenovia, New York, on August 21 and 22, 1850. Madison County, New York, was the abolition headquarters of the country, because of philanthropist and activist Gerrit Smith, who lived in neighboring Peterboro, New York, and called the meeting "in behalf of the New York State Vigilance Committee." A hostile newspaper report refers to the meeting as "Gerrit Smith's Convention". This was one month before the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed by the United States Congress; its passage was a foregone conclusion, and the convention never even discussed how its passage could be prevented. Instead the question was what the existing fugitive slaves were to do, and how their friends could help them. Participants included Frederick Douglass, until recently himself a fugitive slave, the Edmonson sisters, Gerrit Smith, Samuel Joseph May, Theodore Dwight Weld, his wife Angelina Grimké, and others. The convention opened at what the announcement ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ezra Greenleaf Weld (American - Fugitive Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, New York - Google Art Project

Ezra Greenleaf Weld (October 26, 1801 – October 14, 1874), often known simply as "Greenleaf", was a photographer and an operator of a daguerreotype studio in Cazenovia, New York. He and his family were involved with the abolitionist movement. Family Greenleaf was the son of Ludovicus Weld and Elizabeth (Clark) Weld. His brother was Theodore Dwight Weld, one of the most important abolitionists of his era. These Welds are all members of the very notable Weld Family of New England and share ancestry with Tuesday Weld, William Weld, and others. Personal life Weld was born in Hampton, Connecticut, and lived there until 1825 when his family moved to Pompey, New York. He married Mary Ann Parker on August 16, 1827. Mary died on April 30, 1831, soon after giving birth to her second child. After moving to Cazenovia, Ezra remarried to Deborah Richmond Wood on April 12, 1840, and they later had four children. Photography Weld opened his first studio in his home in 1845. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Angelina Grimké

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld (February 20, 1805 – October 26, 1879) was an American abolitionist, political activist, women's rights advocate, and supporter of the women's suffrage movement. She and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were considered the only notable examples of white Southern women abolitionists.Gerda Lerner"The Grimke Sisters and the Struggle Against Race Prejudice" ''The Journal of Negro History'', Vol. 48, No. 4 (October 1963), pp. 277–91. Retrieved September 21, 2016. The sisters lived together as adults, while Angelina was the wife of abolitionist leader Theodore Dwight Weld. Although raised in Charleston, South Carolina, Angelina and Sarah spent their entire adult lives in the North. Angelina's greatest fame was between 1835, when William Lloyd Garrison published a letter of hers in his anti-slavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', and May 1838, when she gave a speech to abolitionists with a hostile, noisy, stone-throwing crowd outside Pennsylvania Ha ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a City (New York), city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, Yonkers, New York, Yonkers, and Rochester, New York, Rochester. At the United States Census 2020, 2020 census, the city's population was 148,620 and its Syracuse metropolitan area, metropolitan area had a population of 662,057. It is the economic and educational hub of Central New York, a region with over one million inhabitants. Syracuse is also well-provided with convention sites, with a Oncenter, downtown convention complex. Syracuse was named after the classical Greek city Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse (''Siracusa'' in Italian), a city on the eastern coast of the Italian island of Sicily. Historically, the city has functioned as a major Crossroads (culture), crossroads over the last two centuries, first between the Erie Canal and its ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Peterboro

Peterboro, located approximately southeast of Syracuse, New York, is a historic hamlet and currently the administrative center for the Town of Smithfield, Madison County, New York, United States. Peterboro has a Post Office, ZIP code 13134. Because of its most famous resident—businessman, philanthropist, and public intellectual Gerrit Smith—Peterboro was before the U.S. Civil War the capital of the U.S. abolition movement. Peterboro was, according to Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, the only place in the country where fugitive slave catchers did not dare show their faces, the only place the New York Anti-Slavery Society could meet (a mob chased it out of Utica), the only place where fugitive slaves ever met as a group—the Fugitive Slave Convention of 1850, held in neighboring Cazenovia because Peterboro was too small for the expected crowd. Abolitionist leaders such as John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and many others were constant guests in Smith's house ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Slave Catchers

In the United States a slave catcher was a person employed to track down and return escaped slaves to their enslavers. The first slave catchers in the Americas were active in European colonies in the West Indies during the sixteenth century. In colonial Virginia and Carolina, slave catchers (as part of the slave patrol system) were recruited by Southern planters beginning in the eighteenth century to return fugitive slaves; the concept quickly spread to the rest of the Thirteen Colonies. After the establishment of the United States, slave catchers continued to be employed in addition to being active in other countries which had not abolished slavery, such as Brazil. The activities of slave catchers from the American South became at the center of a major controversy in the lead up to the American Civil War; the Fugitive Slave Act required those living in the Northern United States to assist slave catchers. Slave catchers in the United States ceased to be active with the ratifi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

John Brown's Raid On Harpers Ferry

John is a common English name and surname: * John (given name) * John (surname) John may also refer to: New Testament Works * Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John * First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John * Second Epistle of John, often shortened to 2 John * Third Epistle of John, often shortened to 3 John People * John the Baptist (died c. AD 30), regarded as a prophet and the forerunner of Jesus Christ * John the Apostle (lived c. AD 30), one of the twelve apostles of Jesus * John the Evangelist, assigned author of the Fourth Gospel, once identified with the Apostle * John of Patmos, also known as John the Divine or John the Revelator, the author of the Book of Revelation, once identified with the Apostle * John the Presbyter, a figure either identified with or distinguished from the Apostle, the Evangelist and John of Patmos Other people with the given name Religious figures * John, father of Andrew the Apostle and Saint Peter * Pope Joh ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Secret Six

The so-called Secret Six, or the Secret Committee of Six, were a group of men who secretly funded the 1859 raid on Harper's Ferry by abolitionist John Brown. Sometimes described as "wealthy," this was true of only two. The other four were in positions of influence, and could, therefore, encourage others to contribute to "the cause." The name "Secret Six" was invented by writers long after Brown's death. The term never appears in the testimony at Brown's trial, in James Redpath's ''The public life of Capt. John Brown'' (1859), or in the ''Memoirs of John Brown'' of Franklin Benjamin Sanborn (1878). The men involved helped Brown as individuals and did not work together or correspond with each other. They were never in the same room at the same time, and in some cases barely knew each other. Background The Secret Six were Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Samuel Gridley Howe, Theodore Parker, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, Gerrit Smith, and George Luther Stearns. All six had been involved ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Daguerrotype

Daguerreotype (; french: daguerréotype) was the first publicly available photographic process; it was widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. "Daguerreotype" also refers to an image created through this process. Invented by Louis Daguerre and introduced worldwide in 1839, the daguerreotype was almost completely superseded by 1860 with new, less expensive processes, such as ambrotype (collodion process), that yield more readily viewable images. There has been a revival of the daguerreotype since the late 20th century by a small number of photographers interested in making artistic use of early photographic processes. To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish; treated it with fumes that made its surface light-sensitive; exposed it in a camera for as long as was judged to be necessary, which could be as little as a few seconds for brightly sunlit subjects or much longer with less intense lighting; made the resulting laten ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ezra Greenleaf Weld

Ezra Greenleaf Weld (October 26, 1801 – October 14, 1874), often known simply as "Greenleaf", was a photographer and an operator of a daguerreotype studio in Cazenovia, New York. He and his family were involved with the abolitionist movement. Family Greenleaf was the son of Ludovicus Weld and Elizabeth (Clark) Weld. His brother was Theodore Dwight Weld, one of the most important abolitionists of his era. These Welds are all members of the very notable Weld Family of New England and share ancestry with Tuesday Weld, William Weld, and others. Personal life Weld was born in Hampton, Connecticut and lived there until 1825 when his family moved to Pompey, New York. He married Mary Ann Parker on August 16, 1827. Mary died on April 30, 1831, soon after giving birth to her second child. After moving to Cazenovia, Ezra remarried to Deborah Richmond Wood on April 12, 1840 and they later had four children. Photography Weld opened his first studio in his home in 1845. In ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Theodore Weld

Theodore Dwight Weld (November 23, 1803 – February 3, 1895) was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 to 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best known for his co-authorship of the authoritative compendium '' American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses'', published in 1839. Harriet Beecher Stowe partly based ''Uncle Tom’s Cabin'' on Weld's text; the latter is regarded as second only to the former in its influence on the antislavery movement. Weld remained dedicated to the abolitionist movement until slavery was ended by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.Columbia 2003 Encyclopedia Article Columbia 2003 Encyclopedia Article According to |

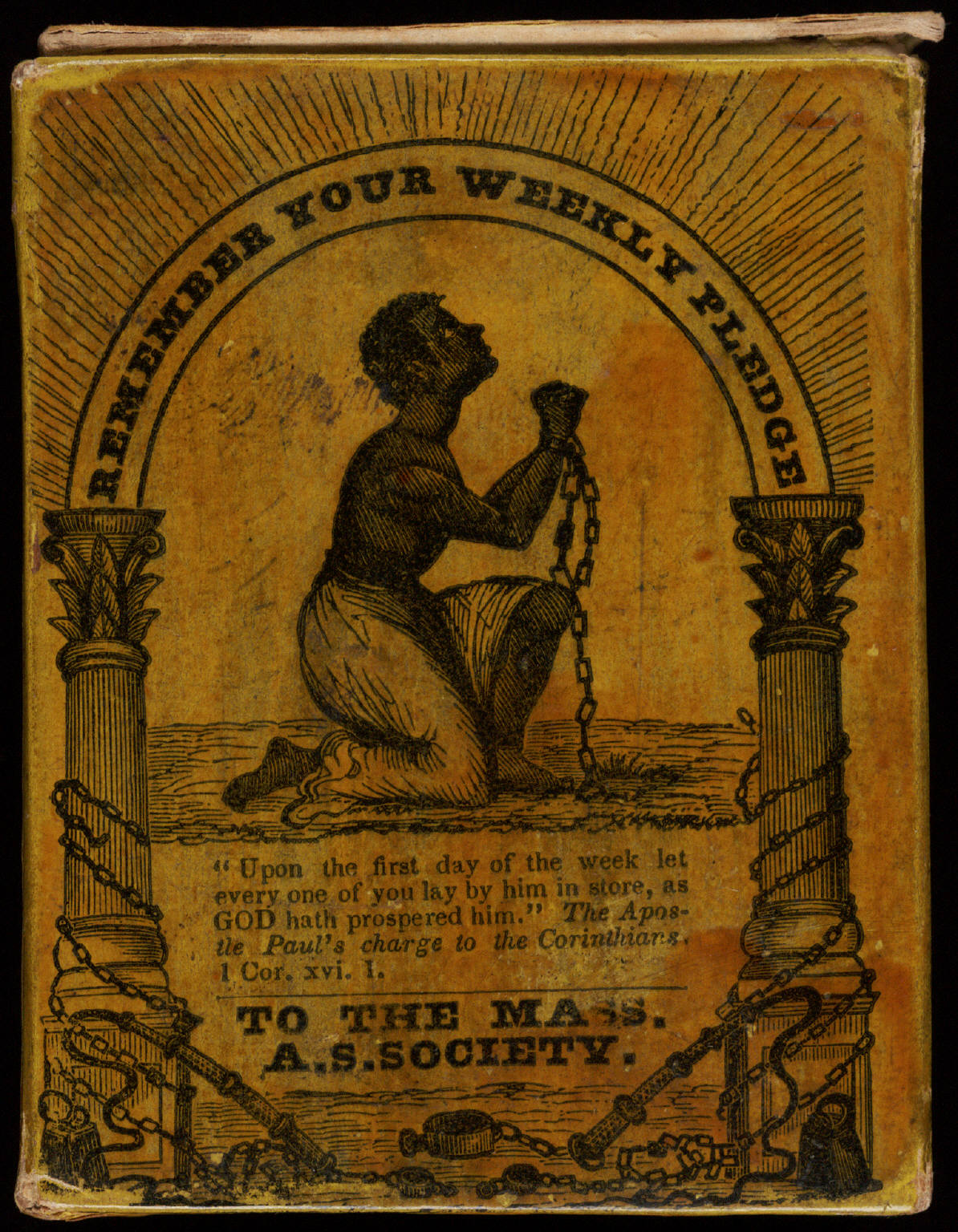

Abolitionism In The United States

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the late colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (ratified 1865). The anti-slavery movement originated during the Age of Enlightenment, focused on ending the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In Colonial America, a few German Quakers issued the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery, which marks the beginning of the American abolitionist movement. Before the Revolutionary War, evangelical colonists were the primary advocates for the opposition to slavery and the slave trade, doing so on humanitarian grounds. James Oglethorpe, the founder of the colony of Georgia, originally tried to prohibit slavery upon its founding, a decision that was eventually reversed. During the Revolutionary era, all states abolished the international sla ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fugitive Slave

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freedom seekers to avoid implying that the slave had committed a crime and that the slaveholder was the injured party. Generally, they tried to reach states or territories where slavery was banned, including Canada, or, until 1821, Spanish Florida. Most slave law tried to control slave travel by requiring them to carry official passes if traveling without a master. Passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increased penalties against runaway slaves and those who aided them. Because of this, some freedom seekers left the United States altogether, traveling to Canada or Mexico. Approximately 100,000 American slaves escaped to freedom. Laws Beginning in 1643, the slave laws were enacted in Colonial America, initially among the New England Co ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |