|

Cell-free Protein Synthesis

Cell-free protein synthesis, also known as ''in vitro'' protein synthesis or CFPS, is the production of protein using biological machinery in a cell-free system, that is, without the use of living cells. The ''in vitro'' protein synthesis environment is not constrained by a cell wall or homeostasis conditions necessary to maintain cell viability. Thus, CFPS enables direct access and control of the translation environment which is advantageous for a number of applications including co-translational solubilisation of membrane proteins, optimisation of protein production, incorporation of non-natural amino acids, selective and site-specific labelling. Due to the open nature of the system, different expression conditions such as pH, redox potentials, temperatures, and chaperones can be screened. Since there is no need to maintain cell viability, toxic proteins can be produced. Introduction Common components of a cell-free reaction include a cell extract, an energy source, a supply of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

In Vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in biology and its subdisciplines are traditionally done in labware such as test tubes, flasks, Petri dishes, and microtiter plates. Studies conducted using components of an organism that have been isolated from their usual biological surroundings permit a more detailed or more convenient analysis than can be done with whole organisms; however, results obtained from ''in vitro'' experiments may not fully or accurately predict the effects on a whole organism. In contrast to ''in vitro'' experiments, ''in vivo'' studies are those conducted in living organisms, including humans, and whole plants. Definition ''In vitro'' ( la, in glass; often not italicized in English usage) studies are conducted using components of an organism that have been isolated fro ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as regulatory sequences (see non-coding DNA), and often a substantial fraction of 'junk' DNA with no evident function. Almost all eukaryotes have mitochondria and a small mitochondrial genome. Algae and plants also contain chloroplasts with a chloroplast genome. The study of the genome is called genomics. The genomes of many organisms have been sequenced and various regions have been annotated. The International Human Genome Project reported the sequence of the genome for ''Homo sapiens'' in 200The Human Genome Project although the initial "finished" sequence was missing 8% of the genome consisting mostly of repetitive sequences. With advancements in technology that could handle sequenci ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

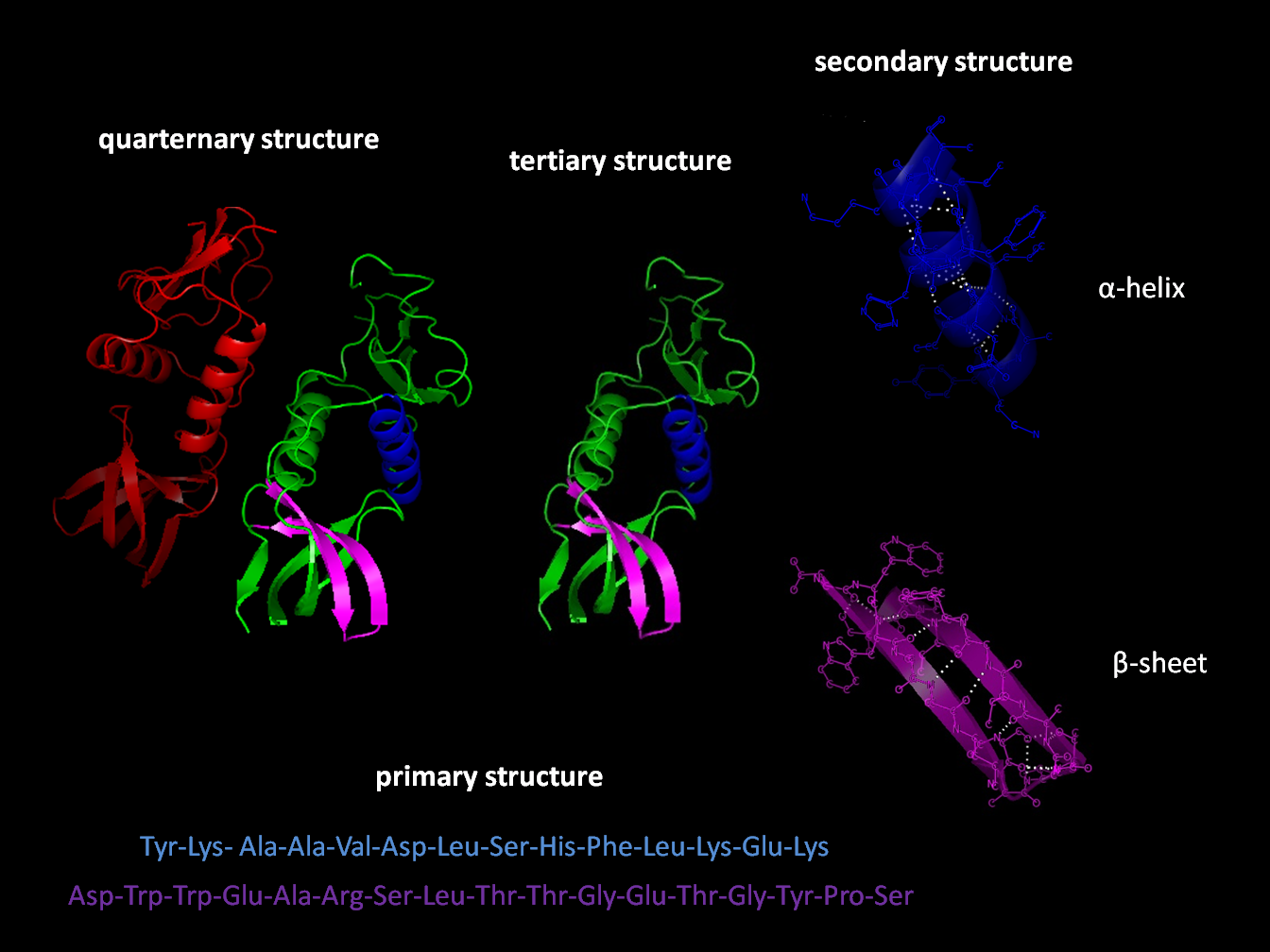

Protein Structure

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers specifically polypeptides formed from sequences of amino acids, the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monomer may also be called a ''residue'' indicating a repeating unit of a polymer. Proteins form by amino acids undergoing condensation reactions, in which the amino acids lose one water molecule per reaction in order to attach to one another with a peptide bond. By convention, a chain under 30 amino acids is often identified as a peptide, rather than a protein. To be able to perform their biological function, proteins fold into one or more specific spatial conformations driven by a number of non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, Van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic packing. To understand the functions of proteins at a molecular level, it is often necessary to determine their three-dimensional structure. This is t ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

In Vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, and plants, as opposed to a tissue extract or dead organism. This is not to be confused with experiments done ''in vitro'' ("within the glass"), i.e., in a laboratory environment using test tubes, Petri dishes, etc. Examples of investigations ''in vivo'' include: the pathogenesis of disease by comparing the effects of bacterial infection with the effects of purified bacterial toxins; the development of non-antibiotics, antiviral drugs, and new drugs generally; and new surgical procedures. Consequently, animal testing and clinical trials are major elements of ''in vivo'' research. ''In vivo'' testing is often employed over ''in vitro'' because it is better suited for observing the overall effects of an experiment on a living subject. In dr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Creatine Phosphate

Phosphocreatine, also known as creatine phosphate (CP) or PCr (Pcr), is a phosphorylated form of creatine that serves as a rapidly mobilizable reserve of high-energy phosphates in skeletal muscle, myocardium and the brain to recycle adenosine triphosphate, the energy currency of the cell. Chemistry In the kidneys, the enzyme AGAT catalyzes the conversion of two amino acids — arginine and glycine — into guanidinoacetate (also called glycocyamine or GAA), which is then transported in the blood to the liver. A methyl group is added to GAA from the amino acid methionine by the enzyme GAMT, forming non-phosphorylated creatine. This is then released into the blood by the liver where it travels mainly to the muscle cells (95% of the body's creatine is in muscles), and to a lesser extent the brain, heart, and pancreas. Once inside the cells it is transformed into phosphocreatine by the enzyme complex creatine kinase. Phosphocreatine is able to donate its phosphate group to convert ad ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Acetyl Phosphate

In organic chemistry, acetyl is a functional group with the chemical formula and the structure . It is sometimes represented by the symbol Ac (not to be confused with the element actinium). In IUPAC nomenclature, acetyl is called ethanoyl, although this term is barely heard. The acetyl group contains a methyl group () single-bonded to a carbonyl (). The carbonyl center of an acyl radical has one nonbonded electron with which it forms a chemical bond to the remainder ''R'' of the molecule. The acetyl moiety is a component of many organic compounds, including acetic acid, the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, acetyl-CoA, acetylcysteine, acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol), and acetylsalicylic acid (also known as aspirin). Acetylation In nature The introduction of an acetyl group into a molecule is called acetylation. In biological organisms, acetyl groups are commonly transferred from acetyl-CoA to other organic molecules. Acetyl-CoA is an intermediate both ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Phosphoenolpyruvic Acid

Phosphoenolpyruvate (2-phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP) is the ester derived from the enol of pyruvate and phosphate. It exists as an anion. PEP is an important intermediate in biochemistry. It has the highest-energy phosphate bond found (−61.9 kJ/mol) in organisms, and is involved in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. In plants, it is also involved in the biosynthesis of various aromatic compounds, and in carbon fixation; in bacteria, it is also used as the source of energy for the phosphotransferase system. In glycolysis PEP is formed by the action of the enzyme enolase on 2-phosphoglyceric acid. Metabolism of PEP to pyruvic acid by pyruvate kinase (PK) generates adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via substrate-level phosphorylation. ATP is one of the major currencies of chemical energy within cells. In gluconeogenesis PEP is formed from the decarboxylation of oxaloacetate and hydrolysis of one guanosine triphosphate molecule. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme phosphoeno ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Incubator (culture)

An incubator is a device used to grow and maintain microbiological cultures or cell cultures. The incubator maintains optimal temperature, humidity and other conditions such as the CO2 and oxygen content of the atmosphere inside. Incubators are essential for much experimental work in cell biology, microbiology and molecular biology and are used to culture both bacterial and eukaryotic cells. An incubator is made up of a chamber with a regulated temperature. Some incubators also regulate humidity, gas composition, or ventilation within that chamber. The simplest incubators are insulated boxes with an adjustable heater, typically going up to 60 to 65 °C (140 to 150 °F), though some can go slightly higher (generally to no more than 100 °C). The most commonly used temperature both for bacteria such as the frequently used E. coli as well as for mammalian cells is approximately 37 °C (99 °F), as these organisms grow well under such conditions. For other organisms used in biologi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Polymerase Chain Reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) to a large enough amount to study in detail. PCR was invented in 1983 by the American biochemist Kary Mullis at Cetus Corporation; Mullis and biochemist Michael Smith (chemist), Michael Smith, who had developed other essential ways of manipulating DNA, were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993. PCR is fundamental to many of the procedures used in genetic testing and research, including analysis of Ancient DNA, ancient samples of DNA and identification of infectious agents. Using PCR, copies of very small amounts of DNA sequences are exponentially amplified in a series of cycles of temperature changes. PCR is now a common and often indispensable technique used in medical laboratory research for a broad variety of applications ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Linear Expression Templates

Linearity is the property of a mathematical relationship (''function'') that can be graphically represented as a straight line. Linearity is closely related to '' proportionality''. Examples in physics include rectilinear motion, the linear relationship of voltage and current in an electrical conductor (Ohm's law), and the relationship of mass and weight. By contrast, more complicated relationships are ''nonlinear''. Generalized for functions in more than one dimension, linearity means the property of a function of being compatible with addition and scaling, also known as the superposition principle. The word linear comes from Latin ''linearis'', "pertaining to or resembling a line". In mathematics In mathematics, a linear map or linear function ''f''(''x'') is a function that satisfies the two properties: * Additivity: . * Homogeneity of degree 1: for all α. These properties are known as the superposition principle. In this definition, ''x'' is not necessarily a real nu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

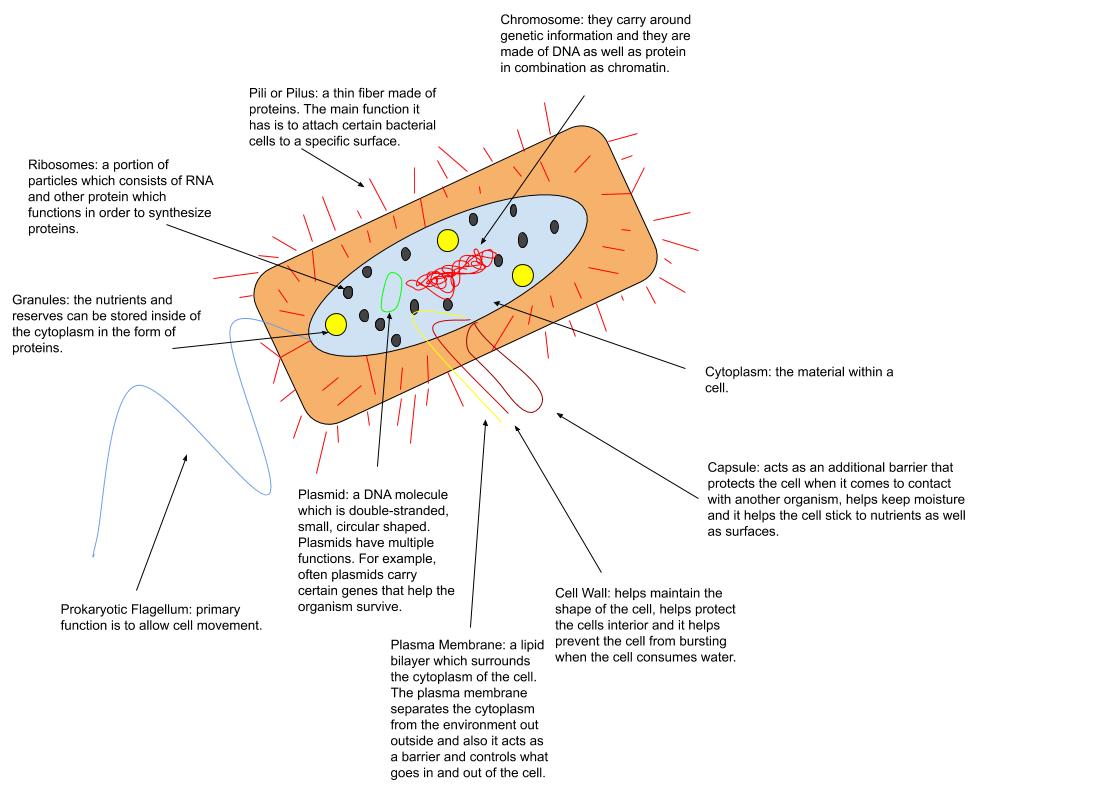

Plasmids

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; however, plasmids are sometimes present in archaea and eukaryotic organisms. In nature, plasmids often carry genes that benefit the survival of the organism and confer selective advantage such as antibiotic resistance. While chromosomes are large and contain all the essential genetic information for living under normal conditions, plasmids are usually very small and contain only additional genes that may be useful in certain situations or conditions. Artificial plasmids are widely used as vectors in molecular cloning, serving to drive the replication of recombinant DNA sequences within host organisms. In the laboratory, plasmids may be introduced into a cell via transformation. Synthetic plasmids are available for procurement over the intern ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nucleases

A nuclease (also archaically known as nucleodepolymerase or polynucleotidase) is an enzyme capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bonds between nucleotides of nucleic acids. Nucleases variously effect single and double stranded breaks in their target molecules. In living organisms, they are essential machinery for many aspects of DNA repair. Defects in certain nucleases can cause genetic instability or immunodeficiency. Nucleases are also extensively used in molecular cloning. There are two primary classifications based on the locus of activity. Exonucleases digest nucleic acids from the ends. Endonucleases act on regions in the ''middle'' of target molecules. They are further subcategorized as deoxyribonucleases and ribonucleases. The former acts on DNA, the latter on RNA. History In the late 1960s, scientists Stuart Linn and Werner Arber isolated examples of the two types of enzymes responsible for phage growth restriction in Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. One of thes ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |