|

Cuprous Oxide

Copper(I) oxide or cuprous oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula Cu2O. It is one of the principal oxides of copper, the other being or copper(II) oxide or cupric oxide (CuO). This red-coloured solid is a component of some antifouling paints. The compound can appear either yellow or red, depending on the size of the particles. Copper(I) oxide is found as the reddish mineral cuprite. Preparation Copper(I) oxide may be produced by several methods. Most straightforwardly, it arises via the oxidation of copper metal: : 4 Cu + O2 → 2 Cu2O Additives such as water and acids affect the rate of this process as well as the further oxidation to copper(II) oxides. It is also produced commercially by reduction of copper(II) solutions with sulfur dioxide. Reactions Aqueous cuprous chloride solutions react with base to give the same material. In all cases, the color is highly sensitive to the procedural details. Formation of copper(I) oxide is the basis of the Fehlin ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cuprite

Cuprite is an oxide mineral composed of copper(I) oxide Cu2O, and is a minor ore of copper. Its dark crystals with red internal reflections are in the isometric system hexoctahedral class, appearing as cubic, octahedral, or dodecahedral forms, or in combinations. Penetration twins frequently occur. In spite of its nice color it is rarely used for jewelry because of its low Mohs hardness of 3.5 to 4. It has a relatively high specific gravity of 6.1, imperfect cleavage and is brittle to conchoidal fracture. The luster is sub-metallic to brilliant adamantine. The "chalcotrichite" (from variety typically shows greatly elongated (parallel to 01 capillary or needle like crystals forms. It is a secondary mineral which forms in the oxidized zone of copper sulfide deposits. It frequently occurs in association with native copper, azurite, chrysocolla, malachite, tenorite and a variety of iron oxide minerals.Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis, 1985, ''Manual of Mineralogy,'' 20th ed. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cuprite

Cuprite is an oxide mineral composed of copper(I) oxide Cu2O, and is a minor ore of copper. Its dark crystals with red internal reflections are in the isometric system hexoctahedral class, appearing as cubic, octahedral, or dodecahedral forms, or in combinations. Penetration twins frequently occur. In spite of its nice color it is rarely used for jewelry because of its low Mohs hardness of 3.5 to 4. It has a relatively high specific gravity of 6.1, imperfect cleavage and is brittle to conchoidal fracture. The luster is sub-metallic to brilliant adamantine. The "chalcotrichite" (from variety typically shows greatly elongated (parallel to 01 capillary or needle like crystals forms. It is a secondary mineral which forms in the oxidized zone of copper sulfide deposits. It frequently occurs in association with native copper, azurite, chrysocolla, malachite, tenorite and a variety of iron oxide minerals.Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis, 1985, ''Manual of Mineralogy,'' 20th ed. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

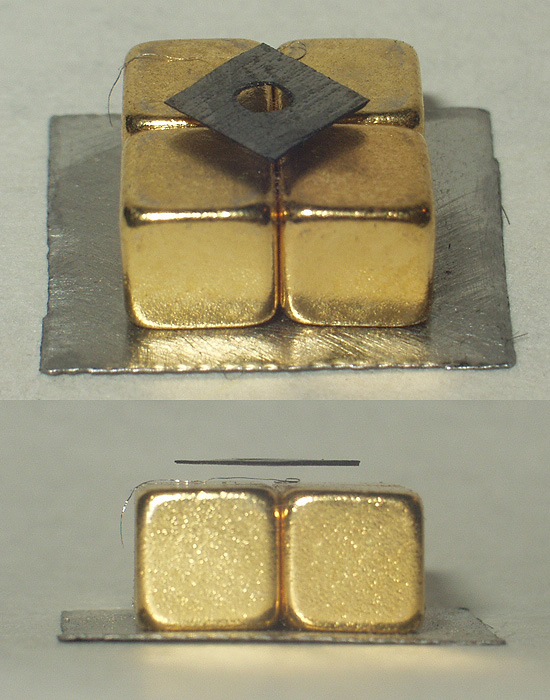

Diamagnetic

Diamagnetic materials are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials are attracted by a magnetic field. Diamagnetism is a quantum mechanical effect that occurs in all materials; when it is the only contribution to the magnetism, the material is called diamagnetic. In paramagnetic and ferromagnetic substances, the weak diamagnetic force is overcome by the attractive force of magnetic dipoles in the material. The magnetic permeability of diamagnetic materials is less than the permeability of vacuum, ''μ''0. In most materials, diamagnetism is a weak effect which can be detected only by sensitive laboratory instruments, but a superconductor acts as a strong diamagnet because it repels a magnetic field entirely from its interior. Diamagnetism was first discovered when Anton Brugmans observed in 1778 that bismuth was repel ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Copper(II) Hydroxide

Copper(II) hydroxide is the hydroxide of copper with the chemical formula of Cu(OH)2. It is a pale greenish blue or bluish green solid. Some forms of copper(II) hydroxide are sold as "stabilized" copper(II) hydroxide, although they likely consist of a mixture of copper(II) carbonate and hydroxide. Cupric hydroxide is a strong base, although its low solubility in water makes this hard to observe directly. Occurrence Copper(II) hydroxide has been known since copper smelting began around 5000 BC although the alchemists were probably the first to manufacture it by mixing solutions of lye (sodium or potassium hydroxide) and blue vitriol (copper(II) sulfate). Sources of both compounds were available in antiquity. It was produced on an industrial scale during the 17th and 18th centuries for use in pigments such as blue verditer and Bremen green. These pigments were used in ceramics and painting. Mineral The mineral of the formula Cu(OH)2 is called spertiniite. Copper(II) hydroxide is ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Red Plague (corrosion)

Red plague is an accelerated corrosion of copper when plated with silver. After storage or use in high-humidity environment, cuprous oxide forms on the surface of the parts. The corrosion is identifiable by presence of patches of brown-red powder deposit on the exposed copper. Red plague is caused by normally occurring electrode potential difference between the copper and silver, leading to galvanic corrosion occurring in pits or breaks in the silver plating. It develops in the presence of moisture and oxygen when the porosity of the silver layer allows them to come in contact with the copper-silver interface. It is an electrochemical corrosion—a copper-silver galvanic cell forms and the copper acts as sacrificial anode A galvanic anode, or sacrificial anode, is the main component of a galvanic cathodic protection system used to protect buried or submerged metal structures from corrosion. They are made from a metal alloy with a more "active" voltage (more n .... In suita ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engineering is the field dedicated to controlling and preventing corrosion. In the most common use of the word, this means electrochemical oxidation of metal in reaction with an oxidant such as oxygen, hydrogen or hydroxide. Rusting, the formation of iron oxides, is a well-known example of electrochemical corrosion. This type of damage typically produces oxide(s) or salt(s) of the original metal and results in a distinctive orange colouration. Corrosion can also occur in materials other than metals, such as ceramics or polymers, although in this context, the term "degradation" is more common. Corrosion degrades the useful properties of materials and structures including strength, appearance and permeability to liquids and gases. Many structural ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. The metal is found in the Earth's crust in the pure, free elemental form ("native silver"), as an alloy with gold and other metals, and in minerals such as argentite and chlorargyrite. Most silver is produced as a byproduct of copper, gold, lead, and zinc Refining (metallurgy), refining. Silver has long been valued as a precious metal. Silver metal is used in many bullion coins, sometimes bimetallism, alongside gold: while it is more abundant than gold, it is much less abundant as a native metal. Its purity is typically measured on a per-mille basis; a 94%-pure alloy is described as "0.940 fine". As one of th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Precipitate

In an aqueous solution, precipitation is the process of transforming a dissolved substance into an insoluble solid from a super-saturated solution. The solid formed is called the precipitate. In case of an inorganic chemical reaction leading to precipitation, the chemical reagent causing the solid to form is called the ''precipitant''. The clear liquid remaining above the precipitated or the centrifuged solid phase is also called the 'supernate' or 'supernatant'. The notion of precipitation can also be extended to other domains of chemistry (organic chemistry and biochemistry) and even be applied to the solid phases (''e.g.'', metallurgy and alloys) when solid impurities segregate from a solid phase. Supersaturation The precipitation of a compound may occur when its concentration exceeds its solubility. This can be due to temperature changes, solvent evaporation, or by mixing solvents. Precipitation occurs more rapidly from a strongly supersaturated solution. The formati ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Alkaline

In chemistry, an alkali (; from ar, القلوي, al-qaly, lit=ashes of the saltwort) is a base (chemistry), basic, ionic compound, ionic salt (chemistry), salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a soluble base has a pH greater than 7.0. The adjective alkaline, and less often, alkalescent, is commonly used in English language, English as a synonym for basic, especially for bases soluble in water. This broad use of the term is likely to have come about because alkalis were the first bases known to obey the acid-base reaction theories#Arrhenius theory, Arrhenius definition of a base, and they are still among the most common bases. Etymology The word "alkali" is derived from Arabic ''al qalīy'' (or ''alkali''), meaning ''the calcined ashes'' (see calcination), referring to the original source of alkaline substances. A water-extract of burned plant ashes, called potash and composed mostly ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double sugars, are molecules made of two bonded monosaccharides; common examples are sucrose (glucose + fructose), lactose (glucose + galactose), and maltose (two molecules of glucose). White sugar is a refined form of sucrose. In the body, compound sugars are hydrolysed into simple sugars. Longer chains of monosaccharides (>2) are not regarded as sugars, and are called oligosaccharides or polysaccharides. Starch is a glucose polymer found in plants, the most abundant source of energy in human food. Some other chemical substances, such as glycerol and sugar alcohols, may have a sweet taste, but are not classified as sugar. Sugars are found in the tissues of most plants. Honey and fruits are abundant natural sources of simple sugars. Suc ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Benedict's Reagent

Benedict's reagent (often called Benedict's qualitative solution or Benedict's solution) is a chemical reagent and complex mixture of sodium carbonate, sodium citrate, and copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate. It is often used in place of Fehling's solution to detect the presence of reducing sugars. The presence of other reducing substances also gives a positive result.Collins Edexcel International GCSEBiology, Student Book () p.42-43 Such tests that use this reagent are called the Benedict's tests. A positive test with Benedict's reagent is shown by a color change from clear blue to brick-red with a precipitate. Generally, Benedict's test detects the presence of aldehydes, alpha-hydroxy-ketones, and hemiacetals, including those that occur in certain ketoses. Thus, although the ketose fructose is not strictly a reducing sugar, it is an alpha-hydroxy-ketone and gives a positive test because the base in the reagent converts it into the aldoses glucose and mannose. Oxidation of the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fehling's Solution

In organic chemistry, Fehling's solution is a chemical reagent used to differentiate between water-soluble carbohydrate and ketone () functional groups, and as a test for reducing sugars and non-reducing sugars, supplementary to the Tollens' reagent test. The test was developed by German chemist Hermann von Fehling in 1849. Laboratory preparation Fehling's solution is prepared by combining two separate solutions: Fehling's A, which is a deep blue aqueous solution of copper(II) sulfate, and Fehling's B, which is a colorless solution of aqueous potassium sodium tartrate (also known as Rochelle salt) made strongly alkali with sodium hydroxide. These two solutions, stable separately, are combined when needed for the test because the copper(II) complex formed by their combination is not stable: it slowly decomposes into copper hydroxide in the alkaline conditions. The active reagent is a tartrate complex of Cu2+, which serves as an oxidizing agent. The tartrate serves as a ligand. Howe ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |