|

Boutonneuse Fever

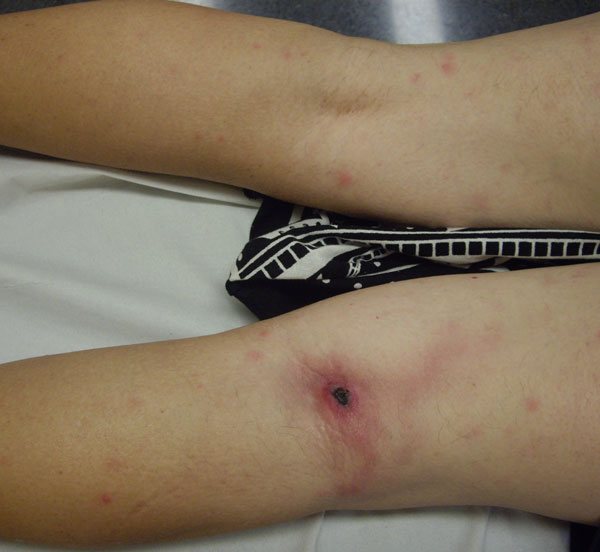

Boutonneuse fever (also called, Mediterranean spotted fever, ''fièvre boutonneuse'', Kenya tick typhus, Indian tick typhus, Marseilles fever, or Astrakhan fever) is a fever as a result of a rickettsial infection caused by the bacterium '' Rickettsia conorii'' and transmitted by the dog tick ''Rhipicephalus sanguineus''. Boutonneuse fever can be seen in many places around the world, although it is endemic in countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. This disease was first described in Tunisia in 1910 by Conor and Bruch and was named ''boutonneuse'' ( French for "spotty") due to its papular skin-rash characteristics. Presentation After an incubation period around seven days, the disease manifests abruptly with chills, high fevers, muscular and articular pains, severe headache, and photophobia. The location of the bite forms a black, ulcerous crust (''tache noire''). Around the fourth day of the illness, a widespread rash appears, first macular and then maculopapular, and sometime ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Eschar

An eschar (; Greek: ''ἐσχάρᾱ'', ''eskhara''; Latin: ''eschara'') is a slough or piece of dead tissue that is cast off from the surface of the skin, particularly after a burn injury, but also seen in gangrene, ulcer, fungal infections, necrotizing spider bite wounds, tick bites associated with spotted fevers and exposure to cutaneous anthrax. The term ‘eschar’ is not interchangeable with ‘scab’. An eschar contains necrotic tissue whereas a scab is composed of dried blood and exudate. Black eschars are most frequently attributed in medicine to cutaneous anthrax (infection by '' Bacillus anthracis''), which may be contracted through herd animal exposure and also from ''Pasteurella multocida'' exposure in cats and rabbits. A newly identified human rickettsial infection, ''R. parkeri'' rickettsiosis, can be differentiated from Rocky Mountain spotted fever by the presence of an eschar at the site of inoculation. Eschar is sometimes called a ''black wound'' becau ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Serologic

Serology is the scientific study of serum and other body fluids. In practice, the term usually refers to the diagnostic identification of antibodies in the serum. Such antibodies are typically formed in response to an infection (against a given microorganism), against other foreign proteins (in response, for example, to a mismatched blood transfusion), or to one's own proteins (in instances of autoimmune disease). In either case, the procedure is simple. Serological tests Serological tests are diagnostic methods that are used to identify antibodies and antigens in a patient's sample. Serological tests may be performed to diagnose infections and autoimmune illnesses, to check if a person has immunity to certain diseases, and in many other situations, such as determining an individual's blood type. Serological tests may also be used in forensic serology to investigate crime scene evidence. Several methods can be used to detect antibodies and antigens, including ELISA, agglutination, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial disease spread by ticks. It typically begins with a fever and headache, which is followed a few days later with the development of a rash. The rash is generally made up of small spots of bleeding and starts on the wrists and ankles. Other symptoms may include muscle pains and vomiting. Long-term complications following recovery may include hearing loss or loss of part of an arm or leg. The disease is caused by ''Rickettsia rickettsii'', a type of bacterium that is primarily spread to humans by American dog ticks, Rocky Mountain wood ticks, and brown dog ticks. Rarely the disease is spread by blood transfusions. Diagnosis in the early stages is difficult. A number of laboratory tests can confirm the diagnosis but treatment should be begun based on symptoms. It is within a group known as spotted fever rickettsiosis, together with ''Rickettsia parkeri'' rickettsiosis, Pacific Coast tick fever, and rickettsialpox. Treatment of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fluoroquinolones

A quinolone antibiotic is a member of a large group of broad-spectrum antibiotic, broad-spectrum bacteriocidals that share a bicyclic molecule, bicyclic core structure related to the substance 4-Quinolone, 4-quinolone. They are used in human and veterinary medicine to treat bacterial infections, as well as in animal husbandry, specifically poultry production. Nearly all quinolone antibiotics in use are fluoroquinolones, which contain a fluorine atom in their chemical structure and are effective against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. One example is ciprofloxacin, one of the most widely used antibiotics worldwide. Medical uses Fluoroquinolones are often used for genitourinary infections and are widely used in the treatment of hospital-acquired infections associated with urinary catheters. In community-acquired infections, they are recommended only when risk factors for multidrug resistance are present or after other antibiotic regimens have failed. However, fo ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Macrolides

The Macrolides are a class of natural products that consist of a large macrocyclic lactone ring to which one or more deoxy sugars, usually cladinose and desosamine, may be attached. The lactone rings are usually 14-, 15-, or 16-membered. Macrolides belong to the polyketide class of natural products. Some macrolides have antibiotic or antifungal activity and are used as pharmaceutical drugs. Rapamycin is also a macrolide and was originally developed as an antifungal, but is now used as an immunosuppressant drug and is being investigated as a potential longevity therapeutic. Macrolides are bacteriostatic in that they suppress or inhibit bacterial growth rather than killing bacteria completely. Definition In general, any macrocyclic lactone having greater than 8-membered rings are candidates for this class. The macrocycle may contain amino nitrogen, amide nitrogen (but should be differentiated from cyclopeptides), an oxazole ring, or a thiazole ring. Benzene rings are exclu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Chloramphenicol

Chloramphenicol is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes use as an eye ointment to treat conjunctivitis. By mouth or by injection into a vein, it is used to treat meningitis, plague, cholera, and typhoid fever. Its use by mouth or by injection is only recommended when safer antibiotics cannot be used. Monitoring both blood levels of the medication and blood cell levels every two days is recommended during treatment. Common side effects include bone marrow suppression, nausea, and diarrhea. The bone marrow suppression may result in death. To reduce the risk of side effects treatment duration should be as short as possible. People with liver or kidney problems may need lower doses. In young children a condition known as gray baby syndrome may occur which results in a swollen stomach and low blood pressure. Its use near the end of pregnancy and during breastfeeding is typically not recommended. Chloramphenicol is a broad-spectrum ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Doxycycline

Doxycycline is a broad-spectrum tetracycline class antibiotic used in the treatment of infections caused by bacteria and certain parasites. It is used to treat bacterial pneumonia, acne, chlamydia infections, Lyme disease, cholera, typhus, and syphilis. It is also used to prevent malaria in combination with quinine. Doxycycline may be taken by mouth or by injection into a vein. Common side effects include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and an increased risk of sunburn. Use during pregnancy is not recommended. Like other agents of the tetracycline class, it either slows or kills bacteria by inhibiting protein production. It kills malaria by targeting a plastid organelle, the apicoplast. Doxycycline was patented in 1957 and came into commercial use in 1967. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. Doxycycline is available as a generic medicine. In 2020, it was the 79th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with m ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tetracycline Antibiotics

Tetracyclines are a group of broad-spectrum antibiotic compounds that have a common basic structure and are either isolated directly from several species of ''Streptomyces'' bacteria or produced semi-synthetically from those isolated compounds. Tetracycline molecules comprise a linear fused tetracyclic nucleus (rings designated A, B, C and D) to which a variety of functional groups are attached. Tetracyclines are named for their four ("tetra-") hydrocarbon rings ("-cycl-") derivation ("-ine"). They are defined as a subclass of polyketides, having an octahydrotetracene-2-carboxamide skeleton and are known as derivative (chemistry), derivatives of polycyclic naphthacene carboxamide. While all tetracyclines have a common structure, they differ from each other by the presence of chloride, methyl, and hydroxyl groups. These chemical modification, modifications do not change their broad antibacterial activity, but do affect pharmacological properties such as half-life and binding to prot ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Immunofluorescence

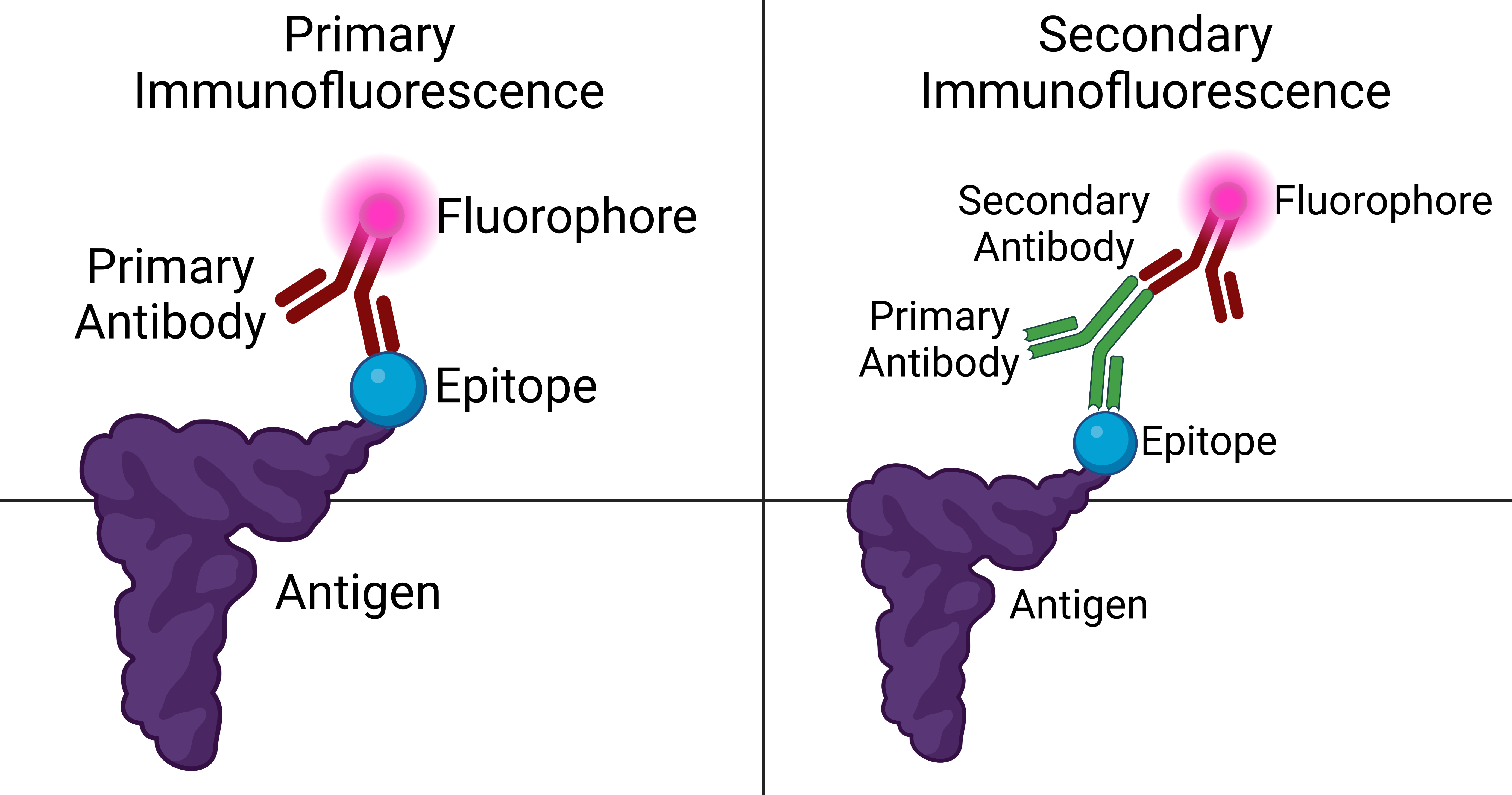

Immunofluorescence is a technique used for light microscopy with a fluorescence microscope and is used primarily on microbiological samples. This technique uses the specificity of antibodies to their antigen to target fluorescent dyes to specific biomolecule targets within a cell, and therefore allows visualization of the distribution of the target molecule through the sample. The specific region an antibody recognizes on an antigen is called an epitope. There have been efforts in epitope mapping since many antibodies can bind the same epitope and levels of binding between antibodies that recognize the same epitope can vary. Additionally, the binding of the fluorophore to the antibody itself cannot interfere with the immunological specificity of the antibody or the binding capacity of its antigen. Immunofluorescence is a widely used example of immunostaining (using antibodies to stain proteins) and is a specific example of immunohistochemistry (the use of the antibody-antigen rel ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay uses a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of a ligand (commonly a protein) in a liquid sample using antibodies directed against the protein to be measured. ELISA has been used as a diagnostic tool in medicine, plant pathology, and biotechnology, as well as a quality control check in various industries. In the most simple form of an ELISA, antigens from the sample to be tested are attached to a surface. Then, a matching antibody is applied over the surface so it can bind the antigen. This antibody is linked to an enzyme and then any unbound antibodies are removed. In the final step, a substance containing the enzyme's substrate is added. If there was binding, the subsequent reaction produces a detectable signal, most commonly a color change. Performing an ELISA involves at least ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Agglutination (biology)

Agglutination is the clumping of particles. The word ''agglutination'' comes from the Latin '' agglutinare'' (glueing to). Agglutination is the process that occurs if an antigen is mixed with its corresponding antibody called isoagglutinin. This term is commonly used in blood grouping. This occurs in biology in two main examples: # The clumping of cells such as bacteria or red blood cells in the presence of an antibody or complement. The antibody or other molecule binds multiple particles and joins them, creating a large complex. This increases the efficacy of microbial elimination by phagocytosis as large clumps of bacteria can be eliminated in one pass, versus the elimination of single microbial antigens. # When people are given blood transfusions of the wrong blood group, the antibodies react with the incorrectly transfused blood group and as a result, the erythrocytes clump up and stick together causing them to agglutinate. The coalescing of small particles that are suspend ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |