|

Bacillus Phage Nf

''Bacillus'' (Latin "stick") is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum ''Bacillota'', with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of other so-shaped bacteria; and the plural ''Bacilli'' is the name of the class of bacteria to which this genus belongs. ''Bacillus'' species can be either obligate aerobes which are dependent on oxygen, or facultative anaerobes which can survive in the absence of oxygen. Cultured ''Bacillus'' species test positive for the enzyme catalase if oxygen has been used or is present. ''Bacillus'' can reduce themselves to oval endospores and can remain in this dormant state for years. The endospore of one species from Morocco is reported to have survived being heated to 420 °C. Endospore formation is usually triggered by a lack of nutrients: the bacterium divides within its cell wall, and one side then engulfs the other. They are not true spores (i.e., not an offspring). Endospore formation ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

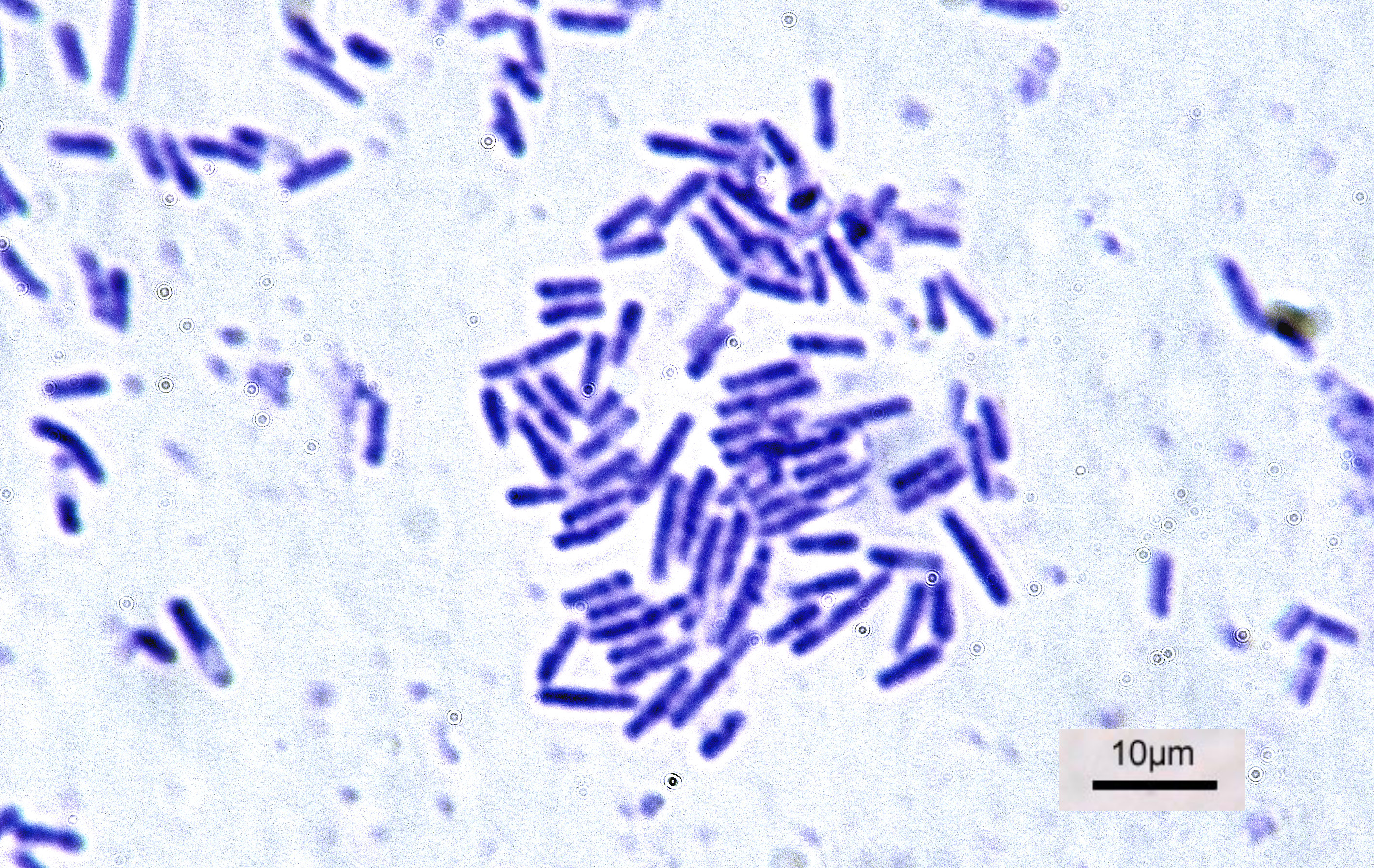

Bacillus Subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'', known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus ''Bacillus'', ''B. subtilis'' is rod-shaped, and can form a tough, protective endospore, allowing it to tolerate extreme environmental conditions. ''B. subtilis'' has historically been classified as an obligate aerobe, though evidence exists that it is a facultative anaerobe. ''B. subtilis'' is considered the best studied Gram-positive bacterium and a model organism to study bacterial chromosome replication and cell differentiation. It is one of the bacterial champions in secreted enzyme production and used on an industrial scale by biotechnology companies. Description ''Bacillus subtilis'' is a Gram-positive bacterium, rod-shaped and catalase-positive. It was originally named ''Vibrio subtilis'' by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, and renamed ''B ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Symbiosis

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasitic. The organisms, each termed a symbiont, must be of different species. In 1879, Heinrich Anton de Bary defined it as "the living together of unlike organisms". The term was subject to a century-long debate about whether it should specifically denote mutualism, as in lichens. Biologists have now abandoned that restriction. Symbiosis can be obligatory, which means that one or more of the symbionts depend on each other for survival, or facultative (optional), when they can generally live independently. Symbiosis is also classified by physical attachment. When symbionts form a single body it is called conjunctive symbiosis, while all other arrangements are called disjunctive symbiosis."symbiosis." Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Surfactin

Surfactin is a very powerful surfactant commonly used as an antibiotic. It is a bacterial cyclic lipopeptide, largely prominent for its exceptional surfactant power. Its amphiphilic properties help this substance to survive in both hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments. It is an antibiotic produced by the Gram-positive endospore-forming bacteria ''Bacillus subtilis''. In the course of various studies of its properties, surfactin was found to exhibit effective characteristics like antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, anti-mycoplasma and hemolytic activities. Structure and Synthesis The structure of the main congener consists of a peptide loop of seven amino acids ( L-glutamic acid, L-leucine, D-leucine, L-valine, L-aspartic acid, D-leucine and L-leucine) and a β-hydroxy fatty acid of variable length, thirteen to fifteen carbon atoms long. The glutamic acid and aspartic acid residues at positions 1 and 5 respectively, give the ring its hydrophilic character, as well as its ne ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Lipopeptide

A lipopeptide is a molecule consisting of a lipid connected to a peptide. They are able to self-assemble into different structures. Many bacteria produced these molecules as a part of their metabolism, especially those of the genus ''Bacillus'', ''Pseudomonas'' and ''Streptomyces''. Certain lipopeptides are used as antibiotics. Other lipopeptides are toll-like receptor agonists. Certain lipopeptides can have strong antifungal and hemolytic activities. It has been demonstrated that their activity is generally linked to interactions with the plasma membrane, and sterol components of the plasma membrane could play a major role in this interaction. It is a general trend that adding a lipid group of a certain length (typically C10–C12) to a lipopeptide will increase its bactericidal activity. Lipopeptides with a higher amount of carbon atoms, for example 14 or 16, in its lipid tail will typically have antibacterial activity as well as anti-fungal activity. Lipopeptide detergents (LPDs ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions. There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are more soluble in hard water, because the polar sulfonate (of detergents) is less likely than the polar carboxylate (of soap) to bind to calcium and other ions found in hard water. Definitions The word ''detergent'' is derived from the Latin adjective ''detergens'', from the verb ''detergere'', meaning to wipe or polish off. Detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions. However, conventionally, detergent is used to mean synthetic cleaning compounds as opposed to ''soap'' (a salt of the natural fatty acid), even though soap is also a detergent in the true sense. In domestic contexts, the term ''detergent'' refers to household cleaning products such as ''laundry detergent'' or '' dish ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Subtilisin

Subtilisin is a protease (a protein-digesting enzyme) initially obtained from ''Bacillus subtilis''. Subtilisins belong to subtilases, a group of serine proteases that – like all serine proteases – initiate the nucleophilic attack on the peptide (amide) bond through a serine residue at the active site. Subtilisins typically have molecular weights 27kDa. They can be obtained from certain types of soil bacteria, for example, ''Bacillus amyloliquefaciens'' from which they are secreted in large amounts. Nomenclature Subtilisin is also commercially known as ''Alcalase®'', ''Endocut-02L'', ''ALK-enzyme'', ''bacillopeptidase'', ''Bacillus subtilis alkaline proteinase bioprase'', ''bioprase AL'', ''colistinase'', ''genenase I'', ''Esperase®'', ''maxatase'', ''protease XXVII'', ''thermoase'', ''superase'', ''subtilisin DY'', ''subtilopeptidase'', ''SP 266'', ''Savinase®'', ''kazusase'', ''protease VIII'', ''protin A 3L'', ''Savinase®'', ''orientase 10B'', ''protease S.'' It ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products. They do this by cleaving the peptide bonds within proteins by hydrolysis, a reaction where water breaks bonds. Proteases are involved in many biological functions, including digestion of ingested proteins, protein catabolism (breakdown of old proteins), and cell signaling. In the absence of functional accelerants, proteolysis would be very slow, taking hundreds of years. Proteases can be found in all forms of life and viruses. They have independently evolved multiple times, and different classes of protease can perform the same reaction by completely different catalytic mechanisms. Hierarchy of proteases Based on catalytic residue Proteases can be classified into seven broad groups: * Serine protease ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Alpha Amylase

α-Amylase is an enzyme (EC 3.2.1.1; systematic name 4-α-D-glucan glucanohydrolase) that hydrolysis, hydrolyses α bonds of large, α-linked polysaccharides, such as starch and glycogen, yielding shorter chains thereof, dextrins, and maltose: :Endohydrolysis of (1→4)-α-D-glucosidic linkages in polysaccharides containing three or more (1→4)-α-linked D-glucose units It is the major form of amylase found in humans and other mammals. It is also present in seeds containing starch as a food reserve, and is secreted by many fungi. It is a member of glycoside hydrolase family 13. In human biology Although found in many tissues, amylase is most prominent in pancreas, pancreatic juice and saliva, each of which has its own isoform of human α-amylase. They behave differently on isoelectric focusing, and can also be separated in testing by using specific monoclonal antibody, monoclonal antibodies. In humans, all amylase isoforms link to chromosome 1p21 (see AMY1A). Salivary a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

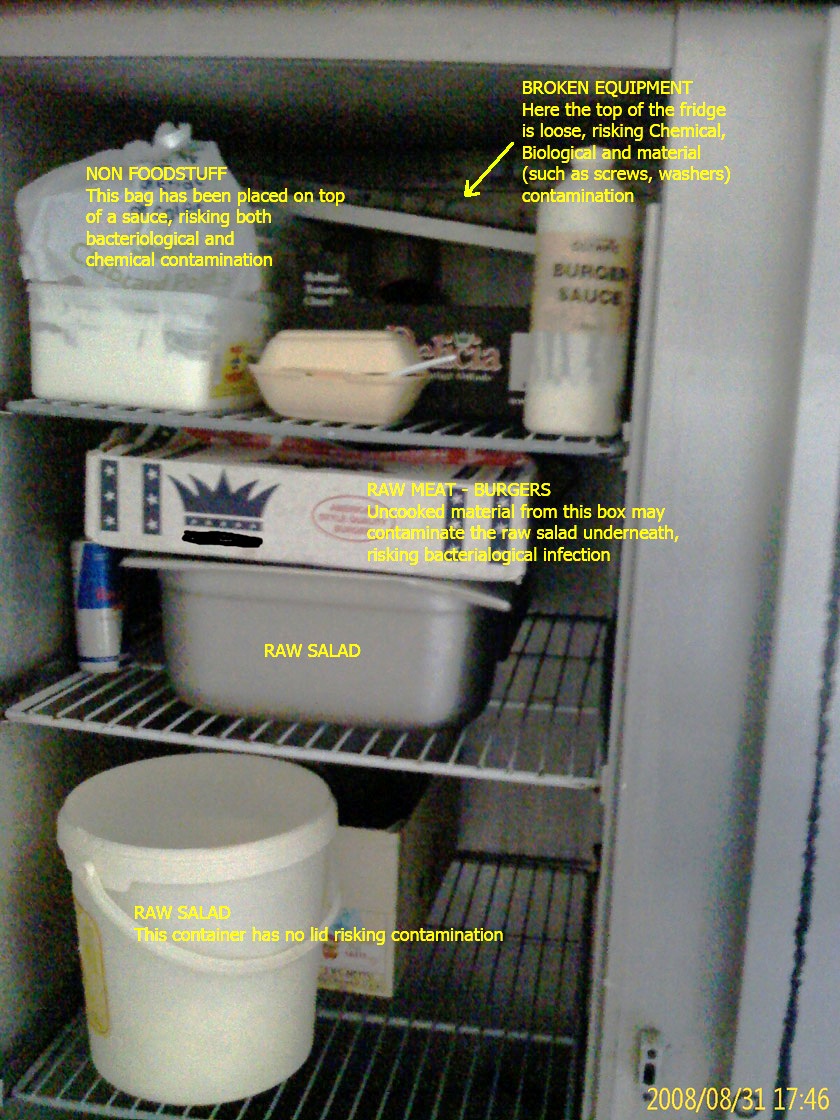

Foodborne Illness

Foodborne illness (also foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the spoilage of contaminated food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites that contaminate food, as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease), and toxins such as aflatoxins in peanuts, poisonous mushrooms, and various species of beans that have not been boiled for at least 10 minutes. Symptoms vary depending on the cause but often include vomiting, fever, and aches, and may include diarrhea. Bouts of vomiting can be repeated with an extended delay in between, because even if infected food was eliminated from the stomach in the first bout, microbes, like bacteria (if applicable), can pass through the stomach into the intestine and begin to multiply. Some types of microbes stay in the intestine. For contaminants requiring an incubation period, symptoms may not manifest for hours to days, depending on the cause and on quantity of consumption. Longer incubation periods tend to c ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacillus Cereus

''Bacillus cereus'' is a Gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium commonly found in soil, food, and marine sponges. The specific name, ''cereus'', meaning "waxy" in Latin, refers to the appearance of colonies grown on blood agar. Some strains are harmful to humans and cause foodborne illness due to their spore-forming nature, while other strains can be beneficial as probiotics for animals, and even exhibit mutualism with certain plants. ''B. cereus'' bacteria may be anaerobes or facultative anaerobes, and like other members of the genus ''Bacillus'', can produce protective endospores. They have a wide range of virulence factors, including phospholipase C, cereulide, sphingomyelinase, metalloproteases, and cytotoxin K, many of which are regulated via quorum sensing. ''B. cereus'' strains exhibit flagellar motility. The ''Bacillus cereus'' group comprises seven closely related species: ''B. cereus'' ''sensu stricto'' (referred to herein as ''B. cereus''), '' B. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The skin form presents with a small blister with surrounding swelling that often turns into a painless ulcer with a black center. The inhalation form presents with fever, chest pain and shortness of breath. The intestinal form presents with diarrhea (which may contain blood), abdominal pains, nausea and vomiting. The injection form presents with fever and an abscess at the site of drug injection. According to the USA's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the first clinical descriptions of cutaneous anthrax were given by Maret in 1752 and Fournier in 1769. Before that anthrax had been described only through historical accounts. The Prussian scientist Robert Koch (1843–1910) was the first to identify ''Bacillus anthracis'' as the bacteri ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacillus Anthracis

''Bacillus anthracis'' is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent ( obligate) pathogen within the genus ''Bacillus''. Its infection is a type of zoonosis, as it is transmitted from animals to humans. It was discovered by a German physician Robert Koch in 1876, and became the first bacterium to be experimentally shown as a pathogen. The discovery was also the first scientific evidence for the germ theory of diseases. ''B. anthracis'' measures about 3 to 5 μm long and 1 to 1.2 μm wide. The reference genome consists of a 5,227,419 bp circular chromosome and two extrachromosomal DNA plasmids, pXO1 and pXO2, of 181,677 and 94,830 bp respectively, which are responsible for the pathogenicity. It forms a protective layer called endospore by which it can remain inactive for many years and suddenly becomes infective under suitable environmental conditions. Because of the resilie ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |