|

Alexander Lavut

Alexander Pavlovich Lavut ( rus, Алекса́ндр Па́влович Лаву́т; 4 July 1929 – 23 June 2013) was a mathematician, dissident and a key figure in the civil rights movement in the Soviet Union. Biography Alexander Lavut was born on 4 July 1929, the son of entrepreneur Pavel Ilyich Lavut (1898–1979), an ebullient figure on the cultural scene of the Soviet 1920s, mentioned in the works of Vladimir Mayakovsky ("that soft-spoken Jew Lavut"). Alexander graduated in 1951 from the Mechanics and Mathematics faculty of Moscow State University. After graduation, he taught at secondary schools in the city, and in Kazakhstan. In 1966–1969, he worked at the Laboratory of Mathematical Geology at Moscow State University. Dissident activities In 1968, like dozens of others, Lavut added his name to an open letter in defense of the poet Alexander Ginzburg. Ginzburg had been arrested as one of the compilers, with Yuri Galanskov, of the ''White Book'' documenting the tr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national republics; in practice, both its government and its economy were highly centralized until its final years. It was a one-party state governed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, with the city of Moscow serving as its capital as well as that of its largest and most populous republic: the Russian SFSR. Other major cities included Leningrad (Russian SFSR), Kiev ( Ukrainian SSR), Minsk ( Byelorussian SSR), Tashkent (Uzbek SSR), Alma-Ata (Kazakh SSR), and Novosibirsk (Russian SFSR). It was the largest country in the world, covering over and spanning eleven time zones. The country's roots lay in the October Revolution of 1917, when the Bolsheviks, under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the Russian Provisional Gove ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

United Nations Commission On Human Rights

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) was a functional commission within the overall framework of the United Nations from 1946 until it was replaced by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2006. It was a subsidiary body of the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), and was also assisted in its work by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNOHCHR). It was the UN's principal mechanism and international forum concerned with the promotion and protection of human rights. On March 15, 2006, the UN General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to replace UNCHR with the UN Human Rights Council. History The UNCHR was established in 1946 by ECOSOC, and was one of the first two "Functional Commissions" set up within the early UN structure (the other being the Commission on the Status of Women). It was a body created under the terms of the United Nations Charter (specifically, under ''Article 68'') to which all UN member states are signatorie ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Khabarovsk

Khabarovsk ( rus, Хабaровск, a=Хабаровск.ogg, r=Habárovsk, p=xɐˈbarəfsk) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative centre of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia,Law #109 located from the China–Russia border, at the confluence of the Amur River, Amur and Ussuri Rivers, about north of Vladivostok. With a Russian Census (2010), 2010 population of 577,441 it is Russia's easternmost city with more than half a million inhabitants. The city was the administrative center of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia from 2002 until December 2018, when Vladivostok took over that role. It is the largest city in the Russian Far East, having overtaken Vladivostok in 2015. It was known as ''Khabarovka'' until 1893. As is typical of the interior of the Russian Far East, Khabarovsk has an #Climate, extreme climate with very strong seasonal swings resulting in strong cold winters and relatively hot and humid summers. History Earliest record ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Butyrka Prison

Butyrskaya prison ( rus, Бутырская тюрьма, r= Butýrskaya tyurmá), usually known simply as Butyrka ( rus, Бутырка, p=bʊˈtɨrkə), is a prison in the Tverskoy District of central Moscow, Russia. In Imperial Russia it served as the central transit prison. During the Soviet Union era (1917-1991) it held many political prisoners. Butyrka remains the largest of Moscow's remand prisons. Overcrowding is an ongoing problem. History The first references to Butyrka prison may be traced back to the 17th century. The current building was erected in 1879 near the Butyrsk gate (, or Butyrskaya zastava) on the site of a prison-fortress which had been built by the architect Matvei Kazakov during the reign of Catherine the Great. The towers of the old fortress once housed the rebellious Streltsy during the reign of Peter I, and later on hundreds of participants of the 1863 January Uprising in Poland. Members of Narodnaya Volya were also prisoners of the Butyrka ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for nuclear disarmament, peace, and human rights. He became renowned as the designer of the Soviet Union's RDS-37, a codename for Soviet development of thermonuclear weapons. Sakharov later became an advocate of civil liberties and civil reforms in the Soviet Union, for which he faced state persecution; these efforts earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. The Sakharov Prize, which is awarded annually by the European Parliament for people and organizations dedicated to human rights and freedoms, is named in his honor. Biography Early life Sakharov was born in Moscow on May 21, 1921. His father was Dmitri Ivanovich Sakharov, a physics professor and an amateur pianist. His father taught at the Second Moscow State University. Andrei's gran ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Moscow Helsinki Group

The Moscow Helsinki Group (also known as the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group, russian: link=no, Московская Хельсинкская группа) is today one of Russia's leading human rights organisations. It was originally set up in 1976 to monitor Soviet compliance with the Helsinki Accords and to report to the West on Soviet human rights abuses. It was forced out of existence in the early 1980s, but revived in 1989 and continues to operate in Russia . However, in late December 2022 the Justice Ministry filed a court order to dissolve the organization. In the 1970s, Moscow Helsinki Group inspired the formation of similar groups in other Warsaw Pact countries and support groups in the West. Within the Soviet Union Helsinki Watch Groups were founded in Ukraine, Lithuania, Georgia and Armenia, as well as in the United States (Helsinki Watch, later Human Rights Watch). Similar initiatives sprung up in countries such as Czechoslovakia with Charter 77. Eventually, the Helsinki ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, in particular the Gulag system. Solzhenitsyn was born into a family that defied the Soviet anti-religious campaign in the 1920s and remained devout members of the Russian Orthodox Church. While still young, Solzhenitsyn lost his faith in Christianity, became an atheist, and embraced Marxism–Leninism. While serving as a captain in the Red Army during World War II, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by the SMERSH and sentenced to eight years in the Gulag and then internal exile for criticizing Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in a private letter. As a result of his experience in prison and the camps, he gradually became a philosophically-minded Eastern Orthodox Christian. As a result of the Khrushchev Thaw, Solzhenitsyn was r ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

The Gulag Archipelago

''The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation'' (russian: Архипелаг ГУЛАГ, ''Arkhipelag GULAG'') is a three-volume non-fiction text written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer and Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. It was first published in 1973, and translated into English and French the following year. It covers life in what is often known as the Gulag, the Soviet forced labour camp system, through a narrative constructed from various sources including reports, interviews, statements, diaries, legal documents, and Solzhenitsyn's own experience as a Gulag prisoner. Following its publication, the book initially circulated in ''samizdat'' underground publication in the Soviet Union until its appearance in the literary journal ''Novy Mir'' in 1989, in which a third of the work was published in three issues. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, ''The Gulag Archipelago'' has been officially published in Russia. Structure As structure ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Political Abuse Of Psychiatry In The Soviet Union

There was systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, based on the interpretation of political opposition or dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent. During the leadership of General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, psychiatry was used to disable and remove from society political opponents ("dissidents") who openly expressed beliefs that contradicted the official dogma. The term "philosophical intoxication", for instance, was widely applied to the mental disorders diagnosed when people disagreed with the country's Communist leaders and, by referring to the writings of the Founding Fathers of Marxism–Leninism—Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin—made them the target of criticism. Article 58-10 of the Stalin-era Criminal Code, "Anti-Soviet agitation", was to a considerable degree preserved in the new 1958 RSFSR Criminal Code as Article 70 "Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda". In 1967, a weaker l ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Anti-Soviet Agitation

Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (ASA) (russian: антисове́тская агита́ция и пропага́нда (АСА)) was a criminal offence in the Soviet Union. To begin with the term was interchangeably used with counter-revolutionary agitation. The latter term was in use immediately after the first Russian Revolution in February 1917. The offence was codified in criminal law in the 1920s, and revised in the 1950s in two articles of the RSFSR Criminal Code. The offence was widely used against Soviet dissidents. Stalin era The new Criminal Codes of the 1920s introduced the offence of ''anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda'' as one of the many forms of counter-revolutionary activity grouped together under Article 58 of the Russian RSFSR Penal Code. The article was put in force on 25 February 1927 and remained in force throughout the period of Stalinism. Article 58:10, "propaganda and agitation that called to overturn or undermining of the Soviet regime", was pu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pyotr Grigorenko

Petro Grigorenko or Petro Hryhorovych Hryhorenko ( uk, Петро́ Григо́рович Григоре́нко, russian: Пётр Григо́рьевич Григоре́нко, link=no, – 21 February 1987) was a high-ranking Soviet Army commander of Ukrainians, Ukrainian descent, who in his fifties became a dissident and a writer, one of the founders of the human rights movement in the Soviet Union. For 16 years, he was a professor of cybernetics at the Frunze Military Academy and chairman of its cybernetic section before joining the ranks of the early dissidents. In the mid-1970s Grigorenko helped to found the Moscow Helsinki Group and the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, before leaving the USSR for medical treatment in the United States. The Soviet government barred his return, and he never again returned to the Soviet Union. In the words of Joseph Alsop, Grigorenko publicly denounced the "totalitarianism that hides behind the mask of so-called Soviet democracy." Early life P ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

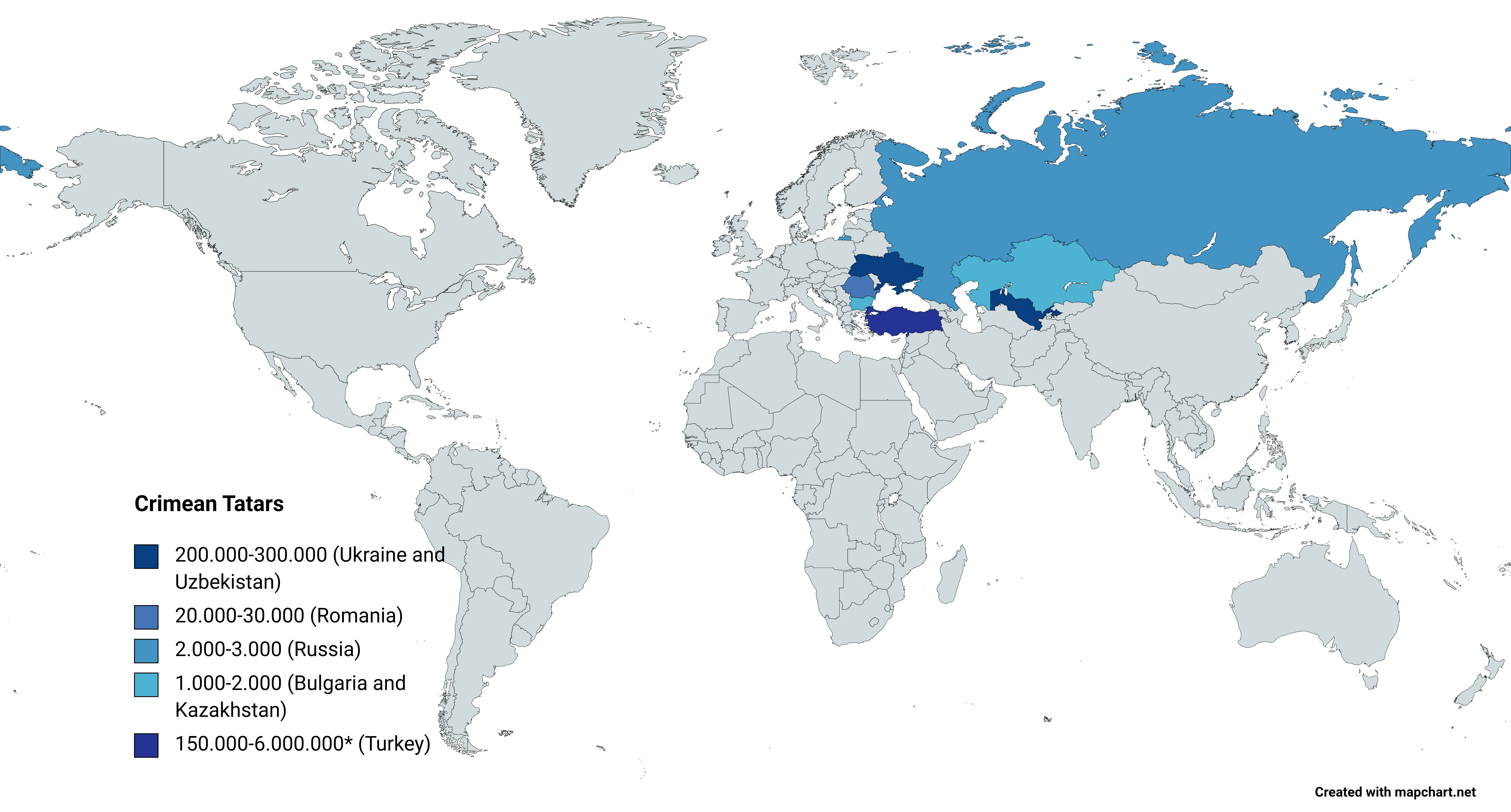

Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg , flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars , image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg , caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace , poptime = , popplace = , region1 = , pop1 = 3,500,000 6,000,000 , ref1 = , region2 = * , pop2 = 248,193 , ref2 = , region3 = , pop3 = 239,000 , ref3 = , region4 = , pop4 = 24,137 , ref4 = , region5 = , pop5 = 2,449 , ref5 = , region7 = , pop7 = 1,803 , ref7 = , region8 = , pop8 = 1,532 , ref8 = , region9 = *() , pop9 = 7,000(500–1,000) , ref9 = , region10 = Total , pop10 = 4.024.114 (or 6.524.11 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

.jpg)