Yup'ik Language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Yupʼik or Yupiaq (sg & pl) and Yupiit or Yupiat (pl), also Central Alaskan Yupʼik, Central Yupʼik, Alaskan Yupʼik ( own name ''Yupʼik'' sg ''Yupiik'' dual ''Yupiit'' pl;

The Yupʼik or Yupiaq (sg & pl) and Yupiit or Yupiat (pl), also Central Alaskan Yupʼik, Central Yupʼik, Alaskan Yupʼik ( own name ''Yupʼik'' sg ''Yupiik'' dual ''Yupiit'' pl;

"Table 16. American Indian and Alaska Native Alone and Alone or in Combination Population by Tribe for Alaska: 2000".

U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000, special tabulation. Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

"Central Alaskan Yupʼik."

''Yupʼik Eskimo Dictionary,'' 2nd edition

Alaska Native Language Center. comes from the Yupʼik word , meaning 'person', plus the postbase (or ), meaning 'real' or 'genuine'; thus, literally means 'real person'.Fienup-Riordan, 1993, p. 10. The ethnographic literature sometimes refers to the Yupʼik people or their language as ''Yuk'' or ''Yuit''. In the Hooper Bay-Chevak and Nunivak dialects of Yupʼik, both the language and the people are given the name . The use of an apostrophe in the name , compared to Siberian , exemplifies Central Yupʼik orthography: "The apostrophe represents gemination r lengtheningof the 'p' sound."Steven A. Jacobson (1984)

''Central Yupʼik and the Schools: A Handbook for Teachers''

. Alaska Native Language Center. Developed by Alaska Department of Education Bilingual/Bicultural Education Programs. Juneau, Alaska, 1984. The following are names given to them by their neighbors. * Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq: (Northern Kodiak), (Southern Kodiak) * Deg Xinag Athabaskan: it. 'downriver people' it. 'coast people' * Holikachuk Athabaskan: it. 'coast people' * Iñupiaq: * Koyukon Athabaskan: it. 'coast people' * Denaʼina Athabaskan: , * Upper Kuskokwim Athabaskan: sg. , pl.

''Alaska Native Land Claims''

The Alaska Native Foundation, Anchorage, Alaska. 2nd edition. Russian Orthodox missionaries went to these islands, where in 1800 priests conducted services in the local language on Kodiak Island, and by 1824 in the Aleutian Islands. An Orthodox priest translated the Holy Scripture and the liturgy into

Navarin Basin sociocultural systems analysis

Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program. Prepared for Bureau of Land Management, Outer Continental Shelf Office, January 1982. The first phase of the Russian period (1745 to 1785) affected only the

''Socioeconomic Review of Alaska's Bristol Bay Region''

Prepared for North Star Group. Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage.

''The Dwellers between: Yupʼik Shamans and Cultural Change in Western Alaska''

Thesis. The University of Montana While the personal experiences of non-natives who visited the Indigenous people of what is now called Alaska formed the basis of early research, by the mid-20th century archaeological excavations in southwestern Alaska allowed scholars to study the effects of foreign trade goods on 19th-century Eskimo material culture. Also, translations of pertinent journals and documents from Russian explorers and the

Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being

'. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

''Conferences of Alaska Native Elders: Our View of Dignified Aging''

Anchorage, Alaska: National Resource Center for American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Elders. December 2004. Traditionally, knowledge was passed down from the elders to the youth through

"The indigenous worldview of Yupiaq culture: its scientific nature and relevance to the practice and teaching of science"

''Journal of Research in Science Teaching'' Vol. 35, #2 A ''naucaqun'' is a lesson or reminder by which the younger generation learns from the experience of the elders. ''Tegganeq'' is derived from the Yupʼik word ''tegge-'' meaning "to be hard; to be tough". Yupʼik discipline is different from Western discipline. The discipline and authority within Yupʼik child-rearing practices have at their core respect for the children. More recently, elders have been invited to attend and present at national conferences and workshops. ''Elders-in-residence'' is a program that involves elders in teaching and curriculum development in a formal educational setting (oftentimes a university), and is intended to influence the content of courses and the way the material is taught.

The Akulmiut: territorial dimensions of a Yupʼik Eskimo society

'. Technical Paper No. 177. Juneau, AK: Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence. Marriages were arranged by parents. Yupʼik societies (regional or socio-territorial groups) were shown to have a band organization characterized by extensive bilaterally structured kinship with multifamily groups aggregating annually.

Traditionally, in the winter the Yupʼik lived in semi-permanent subterranean

Traditionally, in the winter the Yupʼik lived in semi-permanent subterranean  Men's house or Qasgiq (is pronounced as "kaz-geek" and often referred to as ''kashigi, kasgee, kashim, kazhim'', or ''casine'' in the old literature; ''qasgi ~ qasgiq'' sg ''qasgik'' dual ''qasgit'' pl in Yupʼik, ''qaygiq'' sg ''qaygit'' pl in Cupʼik, ''kiiyar'' in Cupʼig; ''qasgimi'' "in the qasgi") is a communal larger sod house. The qasgiq was used and occupied from November through March. The qasgiq housed all adult males in the community and male youth about seven years and older. The women prepared meals in their houses, known as ''ena.'' These were taken to the males in the qasgiq by young women and girls.

The qasgiq served as a school and workshop for young boys, where they could learn the art and craft of

Men's house or Qasgiq (is pronounced as "kaz-geek" and often referred to as ''kashigi, kasgee, kashim, kazhim'', or ''casine'' in the old literature; ''qasgi ~ qasgiq'' sg ''qasgik'' dual ''qasgit'' pl in Yupʼik, ''qaygiq'' sg ''qaygit'' pl in Cupʼik, ''kiiyar'' in Cupʼig; ''qasgimi'' "in the qasgi") is a communal larger sod house. The qasgiq was used and occupied from November through March. The qasgiq housed all adult males in the community and male youth about seven years and older. The women prepared meals in their houses, known as ''ena.'' These were taken to the males in the qasgiq by young women and girls.

The qasgiq served as a school and workshop for young boys, where they could learn the art and craft of

"We are Cupʼit."

Mekoryuk, AK: Nuniwarmiut Piciryarata Tamaryalkuti (Nunivak Cultural Programs). Retrieved on 2004-04-14. * Kusquqvagmiut (Kuskowagamiut), inhabiting the Lower and middle Kuskokwim River.Branson and Troll, 2006, p. xii. Map 3, "Tribal areas, villages and linguistics around 1818, the time of contact." The name derives from ''Kusquqvak'', the Yupʼik name for the Kuskokwim River, possibly meaning "a big thing (river) with a small flow". The Kusquqvagmiut can be further divided into two groups: ** Unegkumiut, inhabiting the Lower Kuskokwim below

The homeland of Yupʼik is the Dfc climate type

The homeland of Yupʼik is the Dfc climate type

Yupʼik (Central Eskimo) Language Guide (and more!), a useful introduction to the Central Eskimo (Yupʼik) Language

World Friendship Publishing, Bethel, Alaska, 2006 Their lands are located in five of the 32

Traditionally,

Traditionally,

Alaska Native Language Center. It is a single well-defined language (now called Yupʼik or Yupʼik and Cupʼik) a

''Alaskan Eskimo Languages population, dialects, and distribution based on 1980 Census''

Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks 1985. Nunivak Island dialect (Cupʼig) is distinct and highly divergent from mainland Yupʼik dialects.

The early schools for Alaska Natives were mostly church-run schools of the Russian Orthodox missions in Russian-controlled Alaska (1799–1867), and, after 1890, the Jesuits and Moravians, allowed the use of the

The early schools for Alaska Natives were mostly church-run schools of the Russian Orthodox missions in Russian-controlled Alaska (1799–1867), and, after 1890, the Jesuits and Moravians, allowed the use of the  17 Yupʼik villages had adopted local elementary bilingual programs by 1973. In the 1980s and 1990s, Yupʼik educators became increasingly networked across village spaces. Between the early 1990s and the run of the century, students in Yupʼik villages, like youth elsewhere became connected to the

17 Yupʼik villages had adopted local elementary bilingual programs by 1973. In the 1980s and 1990s, Yupʼik educators became increasingly networked across village spaces. Between the early 1990s and the run of the century, students in Yupʼik villages, like youth elsewhere became connected to the

Qanemcikarluni Tekitnarqelartuq = One must arrive with a story to tell: Traditional Alaska Native Yupʼik Eskimo Stories in a Culturally Based Math Curriculum

'. ''Journal of American Indian Education'' 46(3): 116–136.

The traditional

The traditional

Yupʼik masks (''kegginaquq'' and ''nepcetaq'' in Yupʼik, ''agayu'' in Cupʼig) are expressive shamanic ritual

Yupʼik masks (''kegginaquq'' and ''nepcetaq'' in Yupʼik, ''agayu'' in Cupʼig) are expressive shamanic ritual

The Milotte Mask Collection

Alaska State Museums Conceps, Second Reprint of Technical Paper Number 2, July 1999 The

Yupʼik dancing (''yuraq'' in Yupʼik) is a traditional form of

Yupʼik dancing (''yuraq'' in Yupʼik) is a traditional form of

"Yupʼik Dance: Old and New"

''The Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement'', Vol. 9, No. 3. pp. 131–149 There are dances for fun, social gatherings, exchange of goods, and thanksgiving. Yupʼik ways of dancing (''yuraryaraq'') embrace six fundamental key entities identified as ''ciuliat'' (ancestors), ''angalkuut'' (shamans), ''cauyaq'' (drum), ''yuaruciyaraq'' (song structures), ''yurarcuutet'' (regalia) and ''yurarvik'' (dance location).Theresa Arevgaq John (2010).

Yuraryararput Kangiit-llu: Our Ways of Dance and Their Meanings

'. University of Alaska Fairbanks. Fairbanks, Alaska. The ''Yuraq'' is used as a generic term for Yupʼik/Cupʼik regular dance. Also, yuraq is concerned with animal behavior and hunting of animals or with the ridicule of individuals (ranging from affectionate teasing to punishing public embarrassment). But, used for inherited dance is ''Yurapik'' or ''Yurapiaq'' (lit. "real dance"). The dancing of their ancestors was banned by Christian missionaries in the late 19th century. After a century, the Cama-i dance festival is a cultural celebration that started in the mid-1980s with the goal to gather dancers from outlying villages to share their music and dances. There are now many groups that perform dances in Alaska. The most popular activity in the Yupʼik-speaking area is rediscovered Yupʼik dancing.

An Eskimo yo-yo or Alaska yo-yo is a traditional two-balled skill toy played and performed by the

An Eskimo yo-yo or Alaska yo-yo is a traditional two-balled skill toy played and performed by the

Keynote Speaker: Christopher (Chris) J. Kiana, M.B.A., MA-RD, Ph.D., candidate

, ''WCSpeakers.com'' (accessed: December 01 2016). The Eskimo yo-yo involves simultaneously swinging two sealskin balls suspended on

Weapon, Toy, or Art? The Eskimo yo-yo as a commodified Arctic bola and marker of cultural Identity

'. University of Alaska Fairbanks. .

Yupʼik

Yupʼik

Muktuk (''mangtak'' in Yukon, Unaliq-Pastuliq, Chevak, ''mangengtak'' in Bristol Bay) is the traditional meal of frozen raw beluga whale skin (dark Epidermis (skin), epidermis) with attached subcutaneous fat (blubber).

Muktuk (''mangtak'' in Yukon, Unaliq-Pastuliq, Chevak, ''mangengtak'' in Bristol Bay) is the traditional meal of frozen raw beluga whale skin (dark Epidermis (skin), epidermis) with attached subcutaneous fat (blubber).

Historically and traditionally, Yupʼik and other all Eskimos traditional religious practices could be very briefly summarised as a form of Shamanism among Eskimo peoples, shamanism based on animism. Aboriginally and in early historic times the Angakkuq, shaman, called as medicine man or medicine woman (''angalkuq'' sg ''angalkuk'' dual ''angalkut'' pl or ''angalkuk'' sg ''angalkuuk'' dual ''angalkuut'' pl in Yupʼik and Cupʼik, ''angalku'' in Cupʼig) was the central figure of Yupʼik religious life and was the middle man between spirits and the humans. The role of the shaman is the primary leader, petitioner, and a trans-mediator between the human and non-human spiritual worlds in association with music, dance, and masks. The shaman's professional responsibility was to enact ancient forms of prayers to request the survival needs of the people. The powerful shaman is called a big shaman (''angarvak'').

Yupʼik shamans directed the making of Yupʼik masks, masks and composed the Yupʼik dancing, dances and music for winter ceremonies. The specified masks depicted survival essentials requested in ceremonies. Shamans often carved the symbolic masks that were vital to many Yupʼik ceremonial dances and these masks represented spirits that the shaman saw during visions.Ahnie Marie Al'aq David Litecky (2011)

Historically and traditionally, Yupʼik and other all Eskimos traditional religious practices could be very briefly summarised as a form of Shamanism among Eskimo peoples, shamanism based on animism. Aboriginally and in early historic times the Angakkuq, shaman, called as medicine man or medicine woman (''angalkuq'' sg ''angalkuk'' dual ''angalkut'' pl or ''angalkuk'' sg ''angalkuuk'' dual ''angalkuut'' pl in Yupʼik and Cupʼik, ''angalku'' in Cupʼig) was the central figure of Yupʼik religious life and was the middle man between spirits and the humans. The role of the shaman is the primary leader, petitioner, and a trans-mediator between the human and non-human spiritual worlds in association with music, dance, and masks. The shaman's professional responsibility was to enact ancient forms of prayers to request the survival needs of the people. The powerful shaman is called a big shaman (''angarvak'').

Yupʼik shamans directed the making of Yupʼik masks, masks and composed the Yupʼik dancing, dances and music for winter ceremonies. The specified masks depicted survival essentials requested in ceremonies. Shamans often carved the symbolic masks that were vital to many Yupʼik ceremonial dances and these masks represented spirits that the shaman saw during visions.Ahnie Marie Al'aq David Litecky (2011)

''The Dwellers Between: Yupʼik Shamans and Cultural Change in Western Alaska''

The University of Montana Shaman masks or plaque masks (''nepcetaq'' sg ''nepcetak'' dual ''nepcetat'' pl) were empowered by shamans and are powerful ceremonial masks represented a shaman's helping spirit (''tuunraq''). Shamans wearing masks of bearded seal, moose, wolf, eagle, beaver, fish, and the north wind were accompanied by drums and music. Legendary animals, monsters, and half-humans: ''amikuk'' (sea monster said to resemble an octopus); ''amlliq'' (monster fish); ''arularaq'' (monster identified as "Bigfoot"); ''cirunelvialuk'' (sea creature); ''cissirpak'' (great worm; ingluilnguq creature that is only half a person); ''inglupgayuk'' (being with half a woman's face); ''irci, irciq'' (creature, half animal and half man); ''itqiirpak'' (big hand from the ocean); ''kun'uniq'' (sea creature with human features seen on pack ice); ''meriiq'' (creature that will suck the blood from one's big toe); ''miluquyuli'' (rock-throwing creature); ''muruayuli'' (creature that sinks into the ground as it walks); ''paalraayak'' (creature that moves underground); ''qamurralek'' (being with a dragging appendage); ''qununiq'' (person who lives in the sea); ''qupurruyuli'' (being with human female face who helps people at sea); ''quq'uyaq'' (polar bear); ''quugaarpak'' (mammoth-like creature that lives underground); ''tengempak'' (giant bird); ''tengmiarpak'' ("Thunderbird (mythology), thunderbird"); ''tiissiq'' (caterpillar-like creature that leaves a scorched trail); ''tumarayuli'' (magical kayak); ''tunturyuaryuk'' (caribou-like creature); ''u͡gayaran'' (giant in Kuskokwim-area folklore); ''ulurrugnaq'' (sea monster said to devour whales); ''uligiayuli'' (ghost said to have a big blanket, which it wraps around children who are out too late at night playing hide-and-seek, it then takes them away); ''yuilriq'' (witch or ghost that walks in the air above the ground and has no liver; a large monster that lives in the mountains and eats people). Legendary humanoids: alirpak little person; ''cingssiik'' (little people having conical hats); ''ciuliaqatuk'' (ancestor identified with the raven); ''egacuayak'' (elf, dwarf); ''kelessiniayaaq'' (little people, said to be spirits of the dead); ''ircenrraq'' ("Little people (mythology), little person" or extraordinary person); ''tukriayuli'' (underground dweller that knocks on the earth's surface).

The Moravian Church is the oldest Protestantism, Protestant denomination in Alaska, and is organized into four provinces in Moravian Church in North America, North America: Northern, Southern, Alaska, and Labrador. The Moravian mission was first founded at Bethel, along the Kuskokwim River in 1885. The mission and reindeer station

The Moravian Church is the oldest Protestantism, Protestant denomination in Alaska, and is organized into four provinces in Moravian Church in North America, North America: Northern, Southern, Alaska, and Labrador. The Moravian mission was first founded at Bethel, along the Kuskokwim River in 1885. The mission and reindeer station

Geographic Dictionary of Alaska

'. Second edition by James McCormick. USGS Bulletin: 299. Washington: Government Printing Office (''Mamterilleq'' literally "site of many caches") or Mumtreklogamute or Mumtrekhlagamute (''Mamterillermiut'' literally "people of Mamterilleq"). In 1885, the Moravian Church established a mission in Bethel, under the leadership of the Kilbucks and John's friend and classmate William H. Weinland (1861–1930) and his wife with carpenter Hans Torgersen. John and Edith Kilbuck, John Henry Kilbuck (1861–1922) and his wife, Edith Margaret Romig (1865–1933), were Moravian missionaries in southwestern Alaska in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.Fienup-Riordan, Ann. (1991). ''The Real People and the Children of Thunder: The Yupʼik Eskimo Encounter With Moravian Missionaries John and Edith Kilbuck''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. John H. Kilbuck was the first Lenape to be ordained as a Moravian minister. They served the Yupʼik, used their language in the Moravian Church in their area, and supported the development of a writing system for Yupʼik. Joseph H. Romig (1872–1951) was a frontier physician and Moravian Church missionary and Edith Margaret's brother, who served as Mayor of Anchorage, Alaska, from 1937 to 1938. Although the resemblances between Yupʼik and Moravian ideology and action may have aided the initial presentation of Christianity, they also masked profound differences in expectation.Fienup-Riordan, Ann. (1990). ''Eskimo Essays: Yupʼik Lives and Howe We See Them''. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. The Society of Jesus is a Christian male Order (religious), religious congregation of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits. In 1888, a Jesuit mission was established on Nelson Island and a year later moved to Akulurak (''Akuluraq'', the former site of St. Mary's Mission) at the mouth of the Yukon River. Segundo Llorente (1906–1989) was a Spanish Jesuit, philosopher, and author who spent 40 years as a missionary among the Yupʼik people in the most remote parts of Alaska. His first mission was at Akulurak. During Christmas Yupʼiks give gifts commemorating the departed.

Samples were collected in 2004 for the Alaska Traditional Diet Project. Prepared by the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. July 19, 2011. Presently, two major problems for the growing population are water and sewage. Water from rivers and lakes is no longer potable as a result of pollution. Wells must be drilled and sewage lagoons built, but there are inherent problems as well. Chamber pots (''qurrun'' in Yupʼik and Cupʼik, ''qerrun'' in Cupʼig) or Bucket toilet, honey buckets with waterless toilets are common in many rural villages in the state of Alaska, such as those in the Bethel area of the Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta. About one-fourth of Alaska's 86,000 Native residents live without running water and use plastic buckets, euphemistically called honey buckets, for toilets.

"Alcohol problems in Alaska Natives: lessons from the Inuit"

''American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research'' 13(1):1–31. As of 2009, about 12% of the deaths among American Indians and Alaska Natives were Alcohol-related death, alcohol-related in the United States overall. Deaths due to alcohol among American Indians are more common in men and among Plains Indians, Northern Plains Indians, but Alaska Natives showed the lowest incidence of death. Existing data do indicate, however, that Alaska Native alcohol-related death rates are almost nine times the national average, and approximately 7% of all Alaska Native deaths are alcohol-related. A 1995-97 study by the Center for Disease Control found that in some continental Amerindian tribes the rate of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder was 1.5 to 2.5 per 1000 live births, more than seven times the national average, while among Alaska natives, the rate of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder was as high as 5.6 per 1000 live births.

"List of resources with contributor: Uyaquq (Helper Neck)".

''UAF: Alaska Native Language Archive''. Accessed 6 Feb 2014.

* Morgan, Lael, ed. (1979). ''Alaska's Native People''. ''Alaska Geographic'' 6(3). Alaska Geographic Society. * Naske, Claus-M. and Herman E. Slotnick. (1987). ''Alaska: A History of the 49th State'', 2nd edition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. * Oswalt, Wendell H. (1967). ''Alaskan Eskimos''. Scranton, PA: Chandler Publishing Company. * Oswalt, Wendell H. (1990). ''Bashful No Longer: An Alaskan Eskimo Ethnohistory, 1778–1988''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. * Pete, Mary. (1993). "Coming to Terms". In Barker, 1993, pp. 8–10. *Irene Reed, Reed, Irene, et al. Yupʼik Eskimo Grammar. Alaska: U of Alaska, 1977. * {{authority control Yupik peoples Alaska Native ethnic groups Native Americans in Alaska Indigenous languages of the North American Subarctic

The Yupʼik or Yupiaq (sg & pl) and Yupiit or Yupiat (pl), also Central Alaskan Yupʼik, Central Yupʼik, Alaskan Yupʼik ( own name ''Yupʼik'' sg ''Yupiik'' dual ''Yupiit'' pl;

The Yupʼik or Yupiaq (sg & pl) and Yupiit or Yupiat (pl), also Central Alaskan Yupʼik, Central Yupʼik, Alaskan Yupʼik ( own name ''Yupʼik'' sg ''Yupiik'' dual ''Yupiit'' pl; Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

: Юпики центральной Аляски), are an Indigenous people of western and southwestern Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

ranging from southern Norton Sound

The Norton Sound ( Inupiaq: ''Imaqpak'') is an inlet of the Bering Sea on the western coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, south of the Seward Peninsula. It is about 240 km (150 mi) long and 200 km (125 mi) wide. The Yukon Riv ...

southwards along the coast of the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta (including living on Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

and Nunivak Islands) and along the northern coast of Bristol Bay

Bristol Bay (, ) is the easternmost arm of the Bering Sea, at 57° to 59° North 157° to 162° West in Southwest Alaska. Bristol Bay is 400 km (250 mi) long and 290 km (180 mi) wide at its mouth. A number of rivers flow in ...

as far east as Nushagak Bay and the northern Alaska Peninsula

The Alaska Peninsula (also called Aleut Peninsula or Aleutian Peninsula, ; Sugpiaq language, Sugpiaq: ''Aluuwiq'', ''Al'uwiq'') is a peninsula extending about to the southwest from the mainland of Alaska and ending in the Aleutian Islands. T ...

at Naknek River and Egegik Bay. They are also known as Cupʼik by the Chevak Cupʼik dialect-speaking people of Chevak and Cupʼig for the Nunivak Cupʼig dialect-speaking people of Nunivak Island.

The Yupiit are the most numerous of the various Alaska Native

Alaska Natives (also known as Native Alaskans, Alaskan Indians, or Indigenous Alaskans) are the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples of Alaska that encompass a diverse arena of cultural and linguistic groups, including the I ...

groups and speak the Central Alaskan Yupʼik language, a member of the Eskimo–Aleut

The Eskaleut ( ), Eskimo–Aleut or Inuit–Yupik–Unangan languages are a language family native to the northern portions of the North American continent, and a small part of northeastern Asia. Languages in the family are indigenous to parts of ...

family of languages. As of the 2010 U.S. Census, the Yupiit population in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

numbered over 34,000 people, of whom over 22,000 lived in Alaska. The vast majority of these live in the seventy or so communities in the traditional Yupʼik territory of western and southwestern Alaska.U.S. Census Bureau. (2004-06-30)"Table 16. American Indian and Alaska Native Alone and Alone or in Combination Population by Tribe for Alaska: 2000".

U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000, special tabulation. Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

Alaska Native Language Center

The Alaska Native Language Center, established in 1972 in Fairbanks, Alaska, is a research center focusing on the research and documentation of the Native languages of Alaska. It publishes grammars, dictionaries, folklore collections and research m ...

. (2001-12-07)"Central Alaskan Yupʼik."

University of Alaska Fairbanks

The University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF or Alaska) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-, National Sea Grant College Program, sea-, and National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program, space-grant research university in ...

. Retrieved on 2014-04-04. The Yupʼik had the greatest number of people who identified with one tribal grouping and no other race (29,000). In that census, nearly half of American Indians and Alaska Natives identified as being of mixed race.

Yupʼik, Cupʼik, and Cupʼig speakers can converse without difficulty, and the regional population is often described using the larger term of ''Yupʼik''. They are one of the four Yupik peoples

The Yupik (; ) are a group of Indigenous or Aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat. Yupik peoples include the following:

* Alutiiq, or Sugp ...

of Alaska and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, closely related to the Sugpiaq ~ Alutiiq (Pacific Yupik) of south-central Alaska, the Siberian Yupik

Siberian Yupiks, or Yuits (), are a Yupik peoples, Yupik people who reside along the coast of the Chukchi Peninsula in the far Russian Far East, northeast of the Russia, Russian Federation and on St. Lawrence Island in Alaska. They speak Si ...

of St. Lawrence Island and Russian Far East, and the Naukan of Russian Far East.

The Yupʼik combine a contemporary and a traditional subsistence lifestyle in a blend unique to the Southwest Alaska

Southwest Alaska is a region of the U.S. state of Alaska. The area is not exactly defined by any governmental administrative region(s); nor does it always have a clear geographic boundary.

Geography

Southwest Alaska includes a huge swath of terr ...

. Today, the Yupʼik generally work and live in western style but still hunt and fish in traditional subsistence ways and gather traditional foods. Most Yupʼik people still speak the native language and bilingual education

In bilingual education, students are taught in two (or more) languages. It is distinct from learning a second language as a subject because both languages are used for instruction in different content areas like math, science, and history. The t ...

has been in force since the 1970s.

The neighbours of the Yupʼik are the Iñupiaq to the north, Aleutized Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq to the south, and Alaskan Athabaskans, such as Yupikized Holikachuk and Deg Hitʼan, non-Yupikized Koyukon and Denaʼina, to the east.

Naming

Originally, the singular form was used in the northern area (Norton Sound,Yukon

Yukon () is a Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada, bordering British Columbia to the south, the Northwest Territories to the east, the Beaufort Sea to the north, and the U.S. state of Alaska to the west. It is Canada’s we ...

, some Nelson Island) while the form was used in the southern area (Kuskokwim, Canineq Kwigillingok, Kipnuk, Kongiganak, Alaska">Kongiganak, and Chefornak, Alaska">Chefornak">Kipnuk, Alaska">Kipnuk, Kongiganak, Alaska">Kongiganak, and Chefornak, Alaska">Chefornak Bristol Bay). Certain places (Chevak, Nunivak, Egegik, Alaska">Egegik) have other forms: , , and .

The form is now used as a common term (though not replacing and ).Jacobson, Steven A. (2012)''Yupʼik Eskimo Dictionary,'' 2nd edition

Alaska Native Language Center. comes from the Yupʼik word , meaning 'person', plus the postbase (or ), meaning 'real' or 'genuine'; thus, literally means 'real person'.Fienup-Riordan, 1993, p. 10. The ethnographic literature sometimes refers to the Yupʼik people or their language as ''Yuk'' or ''Yuit''. In the Hooper Bay-Chevak and Nunivak dialects of Yupʼik, both the language and the people are given the name . The use of an apostrophe in the name , compared to Siberian , exemplifies Central Yupʼik orthography: "The apostrophe represents gemination r lengtheningof the 'p' sound."Steven A. Jacobson (1984)

''Central Yupʼik and the Schools: A Handbook for Teachers''

. Alaska Native Language Center. Developed by Alaska Department of Education Bilingual/Bicultural Education Programs. Juneau, Alaska, 1984. The following are names given to them by their neighbors. * Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq: (Northern Kodiak), (Southern Kodiak) * Deg Xinag Athabaskan: it. 'downriver people' it. 'coast people' * Holikachuk Athabaskan: it. 'coast people' * Iñupiaq: * Koyukon Athabaskan: it. 'coast people' * Denaʼina Athabaskan: , * Upper Kuskokwim Athabaskan: sg. , pl.

History

Origins

The common ancestors of the Yupik and theAleut

Aleuts ( ; (west) or (east) ) are the Indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleuts and the islands are politically divided between the US state of Alaska ...

(as well as various Paleo-Siberian groups) are believed by archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

to have their origin in eastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. Migrating east, they reached the Bering Sea area about 10,000 years ago. Research on blood types

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is comp ...

and linguistics suggests that the ancestors of American Indians reached North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

in waves of migration before the ancestors of the Eskimo and Aleut; there were three major waves of migration from Siberia to the Americas by way of the Bering land bridge

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72° north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of the ...

. This causeway became exposed between 20,000 and 8,000 years ago during periods of glaciation.

By about 3,000 years ago the progenitors of the Yupiit had settled along the coastal areas of what would become western Alaska, with migrations up the coastal rivers—notably the Yukon

Yukon () is a Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada, bordering British Columbia to the south, the Northwest Territories to the east, the Beaufort Sea to the north, and the U.S. state of Alaska to the west. It is Canada’s we ...

and Kuskokwim—around 1400 C.E., eventually reaching as far upriver as Paimiut on the Yukon and Crow Village (''Tulukarugmiut'') on the Kuskokwim.

For centuries, the Yup'ik had fought amongst each other in the Bow and Arrow Wars. According to oral traditions, they may have begun a thousand or 300 years ago, with various different theories as to how the wars begun. Yup'ik tribes constantly raided each other and destroyed villages, These wars ultimately ended in the 1830s and 1840s with the establishment of Russian colonialism.

Before a Russian colonial presence emerged in the area, the Aleut and Yupik spent most of their time sea-hunting animals such as seals, walruses, and sea lions. They used mainly wood, stone, or bone weapons and had limited experience fishing. Families lived together in large groups during the winter and split up into smaller huts during the summer.

Russian colonization

The Russian colonization of the Americas lasted from 1732 to 1867. The Russian Empire supported ships traveling fromSiberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

to America for whaling and fishing expeditions. Gradually the crews established hunting and trading posts

A trading post, trading station, or trading house, also known as a factory in European and colonial contexts, is an establishment or settlement where goods and services could be traded.

Typically a trading post allows people from one geograp ...

of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company in the Aleutian Islands and northern Alaska indigenous settlements. (These were the basis for the Russian-American Company

The Russian-American Company Under the High Patronage of His Imperial Majesty was a state-sponsored chartered company formed largely on the basis of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, United American Company. Emperor Paul I of Russia chartered the c ...

). Approximately half of the fur traders were Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

, such as '' promyshlenniki'' from various European parts of the Russian Empire or from Siberia.

After the Bering expedition in 1741, Russians raced to explore the Aleutian Islands and gain control of its resources. The Indigenous peoples were forced to pay taxes in the form of beaver and seal fur and opted to do so rather than fight the ever-growing stream of Russian hunters.

Grigory Shelikhov

Grigory Ivanovich Shelikhov (Григорий Иванович Шелихов in Russian) (1747, Rylsk, Belgorod Governorate – July 20, 1795 (July 31, 1795 New Style)) was a Russian seafarer, merchant, and fur trader who established a perma ...

led attacks on Kodiak Island

Kodiak Island (, ) is a large island on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, separated from the Alaska mainland by the Shelikof Strait. The largest island in the Kodiak Archipelago, Kodiak Island is the second largest island in the Un ...

against the indigenous Alutiiq

The Alutiiq (pronounced in English; from Promyshlenniki Russian Алеутъ, "Aleut"; plural often "Alutiit"), also called by their ancestral name ( or ; plural often "Sugpiat"), as well as Pacific Eskimo or Pacific Yupik, are a Yupik ...

(Sugpiaqs) in 1784, known as the Awa'uq Massacre. According to some estimates, Russian employees of the trading company killed more than 2,000 Alutiiq. The company then took over control of the island. By the late 1790s, its trading posts had become the centers of permanent settlements of Russian America

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

(1799–1867). Until about 1819, Russian settlement and activity were largely confined to the Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands ( ; ; , "land of the Aleuts"; possibly from the Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', or "island")—also called the Aleut Islands, Aleutic Islands, or, before Alaska Purchase, 1867, the Catherine Archipelago—are a chain ...

, the Pribilof Islands, Kodiak Island

Kodiak Island (, ) is a large island on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, separated from the Alaska mainland by the Shelikof Strait. The largest island in the Kodiak Archipelago, Kodiak Island is the second largest island in the Un ...

, and scattered coastal locations on the mainland.Robert D. rnold (1978)''Alaska Native Land Claims''

The Alaska Native Foundation, Anchorage, Alaska. 2nd edition. Russian Orthodox missionaries went to these islands, where in 1800 priests conducted services in the local language on Kodiak Island, and by 1824 in the Aleutian Islands. An Orthodox priest translated the Holy Scripture and the liturgy into

Tlingit language

The Tlingit language ( ; ' ) is an Indigenous language of the northwestern coast of North America, which is spoken by the Tlingit people of Southeast Alaska and Western Canada and is a branch of the Na-Dene language family. Extensive effor ...

, which was used by other major people of Alaska Natives.

The Russian period, lasting roughly 120 years, can be divided into three 40-year periods: 1745 to 1785, 1785 to 1825, and 1825 to 1865.Ann Fienup-Riordan (1982)Navarin Basin sociocultural systems analysis

Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program. Prepared for Bureau of Land Management, Outer Continental Shelf Office, January 1982. The first phase of the Russian period (1745 to 1785) affected only the

Aleut

Aleuts ( ; (west) or (east) ) are the Indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleuts and the islands are politically divided between the US state of Alaska ...

(Unangan) and Alutiiq

The Alutiiq (pronounced in English; from Promyshlenniki Russian Алеутъ, "Aleut"; plural often "Alutiit"), also called by their ancestral name ( or ; plural often "Sugpiat"), as well as Pacific Eskimo or Pacific Yupik, are a Yupik ...

(Sugpiaq) profoundly. During this period, large sectors of the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

coast were mapped by the English explorer James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

, rather than by the Russians. In 1778, Cook discovered and named Bristol Bay

Bristol Bay (, ) is the easternmost arm of the Bering Sea, at 57° to 59° North 157° to 162° West in Southwest Alaska. Bristol Bay is 400 km (250 mi) long and 290 km (180 mi) wide at its mouth. A number of rivers flow in ...

and then sailed northward around Cape Newenham into Kuskokwim Bay

Kuskokwim Bay is a bay in southwestern Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside ...

.

During the second phase of the Russian period (1785 to 1825), the Shelikhov-Golikov Company and later the Russian-American Company

The Russian-American Company Under the High Patronage of His Imperial Majesty was a state-sponsored chartered company formed largely on the basis of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, United American Company. Emperor Paul I of Russia chartered the c ...

was organized and continued in the exploration of the lucrative north Pacific Ocean sea otter trade. During this time, they exchanged massacres for virtual enslavement and exploitation. The major portion of Alaska remained little known, and the Yupʼik of the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta were not strongly affected. The Russo-American Treaty of 1824 was signed in St. Petersburg between representatives of the Russian Empire and the United States on April 17, 1824, and went into effect on January 12, 1825.

During the last phase of the Russian period (1825 to 1865), the Alaska Natives began to suffer the effects of introduced infectious diseases, to which they had no acquired immunity. In addition, their societies were disrupted by increasing reliance on European trade goods from the permanent Russian trading posts

A trading post, trading station, or trading house, also known as a factory in European and colonial contexts, is an establishment or settlement where goods and services could be traded.

Typically a trading post allows people from one geograp ...

. A third influence was the early Russian Orthodox

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

missionaries, who sought to convert the peoples to their form of Christianity. The missionaries learned native languages, and conducted services in those languages from the early decades of the 19th century. The Treaty of Saint Petersburg of 1825 defined the boundaries between Russian America and British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

claims and possessions in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

.

United States colonization

The United States purchased Alaska from theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

on March 30, 1867. Originally organized as the Department of Alaska (1867–1884), the area was renamed as the District of Alaska

The District of Alaska was the federal government’s designation for Alaska from May 17, 1884, to August 24, 1912, when it became the Territory of Alaska. Previously (1867–1884) it had been known as the Department of Alaska, a military des ...

(1884–1912) and the Territory of Alaska

The Territory of Alaska or Alaska Territory was an Organized incorporated territories of the United States, organized incorporated territory of the United States from August 24, 1912, until Alaska was granted statehood on January 3, 1959. The ...

(1912–1959) before it was admitted to the Union as the State of Alaska (1959–present).

During the Early American Period (1867–1939), the federal government generally neglected the territory, other than using positions in territorial government for political patronage. There was an effort to exploit the natural resources in the years following the purchase of Alaska. Moravian Protestant (1885) and Jesuit Catholic (1888) missions and schools were established along the Kuskokwim and lower Yukon rivers, respectively. The Qasgiq, ceremonial buildings for Yup'ik men, disappeared due to missionary coercion. During the early American period, native languages were forbidden in mission schools, where only English was permitted.

The economy of the islands also took a hit under American ownership. Hutchinson, Cool & Co., an American trading company, took advantage of its position as the only trader in the area and charged the natives as much as possible for its goods. The combination of high costs and low hunting and fishing productivity persisted until the Russo-Japanese war cut off contact with Russia.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was signed into law by U.S. President, President Richard Nixon on December 18, 1971, constituting what is still the largest land claims settlement in United States history. ANCSA was intended to reso ...

(ANCSA) was signed into law on December 18, 1971. The ANCSA is central to both Alaska's history and current Alaska Native economies and political structures.Marie Lowe (2007)''Socioeconomic Review of Alaska's Bristol Bay Region''

Prepared for North Star Group. Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Historiography

Before European contact (until the 1800s), the history of the Yupʼik, like that of otherAlaska Natives

Alaska Natives (also known as Native Alaskans, Alaskan Indians, or Indigenous Alaskans) are the Indigenous peoples of Alaska that encompass a diverse arena of cultural and linguistic groups, including the Iñupiat, Yupik, Aleut, Eyak, Tli ...

, was oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

. Each society or village had storytellers (''qulirarta'') who were known for their memories, and those were the people who told the young about the group's history. Their stories (traditional legends ''qulirat'' and historical narratives ''qanemcit'') express crucial parts of Alaska's earliest history.

The historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

of the Yupʼik ethnohistory

Ethnohistory is the study of cultures and indigenous peoples customs by examining historical records as well as other sources of information on their lives and history. It is also the study of the history of various ethnic groups that may or may ...

, as a part of Eskimology, is slowly emerging. The first academic studies of the Yupʼik tended to generalize all "Eskimo" cultures as homogeneous and changeless.Ahnie Marie Al'aq David Litecky (2011)''The Dwellers between: Yupʼik Shamans and Cultural Change in Western Alaska''

Thesis. The University of Montana While the personal experiences of non-natives who visited the Indigenous people of what is now called Alaska formed the basis of early research, by the mid-20th century archaeological excavations in southwestern Alaska allowed scholars to study the effects of foreign trade goods on 19th-century Eskimo material culture. Also, translations of pertinent journals and documents from Russian explorers and the

Russian-American Company

The Russian-American Company Under the High Patronage of His Imperial Majesty was a state-sponsored chartered company formed largely on the basis of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, United American Company. Emperor Paul I of Russia chartered the c ...

added breadth to the primary source base. The first ethnographic

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

information about the Yupʼik of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta was recorded by the Russian explorer Lieutenant Lavrenty Zagoskin

Lavrenty Alekseyevich Zagoskin (; 21 May 1808 – 22 January 1890) was a Russian naval officer and explorer of Alaska.

Zagoskin was born in 1808 in the Russian district of Penza in a village named Nikolayevka. Even though Nikolayevka was not nea ...

, during his explorations for the Russian-American Company in 1842–1844.

The first academic cultural studies of southwestern Alaskan Indigenous people were developed only in the late 1940s. This was due in part to a dearth of English-language documentation, as well as competition in the field of other subject areas. American anthropologist Margaret Lantis (1906–2006) published ''The Social Culture of the Nunivak Eskimo'' in 1946; it was the first complete description of any Alaskan indigenous group. She began ''Alaskan Eskimo Ceremonialism'' (1947) as a broad study of Alaskan Indigenous people. James W. VanStone (1925–2001), an American cultural anthropologist

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The term s ...

, and Wendell H. Oswalt were among the earliest scholars to undertake significant archaeological research in the Yupʼik region. VanStone demonstrates the ethnographic approach to cultural history in ''Eskimos of the Nushagak River: An Ethnographic History'' (1967). Wendell Oswalt published a comprehensive ethnographic history of the Yukon–Kuskokwim delta region, the longest and most detailed work on Yupʼik history to date in ''Bashful No Longer: An Alaskan Eskimo ethnohistory, 1778–1988'' (1988). Ann Fienup-Riordan (born 1948) began writing extensively about the Yukon-Kuskokwim Indigenous people in the 1980s; she melded Yupʼik voices with traditional anthropology and history in an unprecedented fashion.

The historiography of western Alaska has few Yupʼik scholars contributing writings. Harold Napoleon, an elder of Hooper Bay, presents an interesting premise in his book ''Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being'' (1988). A more scholarly, yet similar, treatment of cultural change can be found in Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley's ''A Yupiaq Worldview: a Pathway to Ecology and Spirit'' (2001), which focuses on the intersection of Western and Yupʼik values.

Yuuyaraq

Yuuyaraq or Way of life (''yuuyaraq'' sg ''yuuyarat'' pl in Yupʼik, ''cuuyaraq'' in Cupʼik, ''cuuyarar'' in Cupig) is the term for the Yupʼik way of life as a human being. The expression encompasses interactions with others, subsistence ortraditional knowledge

Traditional knowledge (TK), indigenous knowledge (IK), folk knowledge, and local knowledge generally refers to knowledge systems embedded in the cultural traditions of regional, indigenous, or local communities.

Traditional knowledge includes ...

, environmental or traditional ecological knowledge

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is a cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans ...

, and understanding

Understanding is a cognitive process related to an abstract or physical object, such as a person, situation, or message whereby one is able to use concepts to model that object.

Understanding is a relation between the knower and an object of u ...

, indigenous psychology, and spiritual balance.

Yuuyaraq defined the correct way of thinking and speaking about all living things, especially the great sea and land mammals on which the Yupʼik relied for food, clothing

Clothing (also known as clothes, garments, dress, apparel, or attire) is any item worn on a human human body, body. Typically, clothing is made of fabrics or textiles, but over time it has included garments made from animal skin and other thin s ...

, shelter, tools, kayaks, and other essentials. These great creatures were sensitive; they were believed able to understand human conversations, and they demanded and received respect. Yuuyaraq prescribed the correct method of hunting and fishing and the correct way of handling all fish and game caught by the hunter in order to honor and appease the spirits and maintain a harmonious relationship with the fish and game. Although unwritten, this way can be compared to Mosaic law

The Law of Moses ( ), also called the Mosaic Law, is the law said to have been revealed to Moses by God. The term primarily refers to the Torah or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible.

Terminology

The Law of Moses or Torah of Moses (Hebr ...

because it governed all aspects of a human being's life.Harold Napoleon (1996). With commentary edited by Eric Madsen. Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being

'. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

Elders

An Alaska Native elder (''tegganeq'' sg ''tegganrek'' dual ''tegganret'' pl in Yupʼik, ''teggneq'' sg ''teggnerek ~ teggenrek'' dual ''teggneret ~ teggenret'' pl in Cupʼik, ''taqnelug'' in Cupʼig) is a respected elder. The elder is defined as an individual who has lived an extended life, maintains a healthy lifestyle, and has a wealth of cultural information and knowledge. The elder has expertise based upon know-how and provides consultation to the community and family when needed.Graves, Kathy (2004)''Conferences of Alaska Native Elders: Our View of Dignified Aging''

Anchorage, Alaska: National Resource Center for American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Elders. December 2004. Traditionally, knowledge was passed down from the elders to the youth through

storytelling

Storytelling is the social and cultural activity of sharing narrative, stories, sometimes with improvisation, theatre, theatrics or embellishment. Every culture has its own narratives, which are shared as a means of entertainment, education, cul ...

. Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley, Delena Norris-Tull, and Roger A. Norris-Tull (1998)"The indigenous worldview of Yupiaq culture: its scientific nature and relevance to the practice and teaching of science"

''Journal of Research in Science Teaching'' Vol. 35, #2 A ''naucaqun'' is a lesson or reminder by which the younger generation learns from the experience of the elders. ''Tegganeq'' is derived from the Yupʼik word ''tegge-'' meaning "to be hard; to be tough". Yupʼik discipline is different from Western discipline. The discipline and authority within Yupʼik child-rearing practices have at their core respect for the children. More recently, elders have been invited to attend and present at national conferences and workshops. ''Elders-in-residence'' is a program that involves elders in teaching and curriculum development in a formal educational setting (oftentimes a university), and is intended to influence the content of courses and the way the material is taught.

Society

Kinship

The Yupʼikkinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

is based on what is formally classified in academia as an Eskimo kinship

Eskimo kinship (or Inuit kinship in Canada) is a category of kinship used to define family organization in anthropology. Identified by Lewis H. Morgan in his 1871 work ''Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family'', the Eskimo syst ...

or lineal kinship. This kinship system is bilateral and a basic social unit consisting of from two to four generations, including parents, offspring, and parents' parents. Kinship terminologies in the Yupʼik societies exhibit a Yuman type of social organization

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and groups. Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, struc ...

with bilateral descent, and Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

cousin terminology. Bilateral descent provides each individual with his or her own unique set of relatives or kindred: some consanguineal members from the father's kin group and some from the mother's, with all four grandparents affiliated equally with the individual. Parallel cousins are referenced by the same terms as siblings, and cross cousins are differentiated.Elisabeth F. Andrews (1989), The Akulmiut: territorial dimensions of a Yupʼik Eskimo society

'. Technical Paper No. 177. Juneau, AK: Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence. Marriages were arranged by parents. Yupʼik societies (regional or socio-territorial groups) were shown to have a band organization characterized by extensive bilaterally structured kinship with multifamily groups aggregating annually.

Community

The Yupʼik created larger settlements in winter to take advantage of group subsistence activities. Villages were organized in certain ways. Cultural rules of kinship served to define relationships among the individuals of the group. Villages ranged in size from just two to more than a dozensod house

The sod house or soddy was a common alternative to the log cabin during frontier settlement of the Great Plains of North America in the 1800s and early 1900s. Primarily used at first for animal shelters, corrals, and fences, they came into use ...

s (''ena'') for women and girls, one (or more in large villages) '' qasgiq'' for men and boys, and warehouse

A warehouse is a building for storing goods. Warehouses are used by manufacturers, importers, exporters, wholesalers, transport businesses, customs, etc. They are usually large plain buildings in industrial parks on the rural–urban fringe, out ...

s.

Leadership

Formerly, social status was attained by successful hunters who could provide food and skins. Successful hunters were recognized as leaders by members of the social group.Tina D. Delapp (1991), "American Eskimos: the Yupʼik and Inupiat." In Joyce Newman Giger (eds.), ''Transcultural nursing: assessment and intervention''. Although there were no formally recognized leaders, informalleadership

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

was practiced by or in the men who held the title ''Nukalpiaq'' ("man in his prime; successful hunter and good provider"). The ''nukalpiaq'', or good provider, was a man of considerable importance in village life. This man was consulted in any affair of importance affecting the village in general, particularly in determining participation in the ''Kevgiq'' and ''Itruka'ar'' ceremonies. He was said to be a major contributor to those ceremonies and provider to orphans and widows.

The position of the ''nukalpiaq'' was not, however, comparable to that of the ''umialik'' (whaling captain) of northern and northwestern Alaska Iñupiaq. The captain had the power to collect the surplus of the village and much of the basic production of individual family members and later redistribute it.

Residence

Traditionally, in the winter the Yupʼik lived in semi-permanent subterranean

Traditionally, in the winter the Yupʼik lived in semi-permanent subterranean house

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air c ...

s, with some for the men and others for the women (with their children). The Yupʼik men lived together in a larger communal house (''qasgiq''), while women and children lived in smaller, different sod house

The sod house or soddy was a common alternative to the log cabin during frontier settlement of the Great Plains of North America in the 1800s and early 1900s. Primarily used at first for animal shelters, corrals, and fences, they came into use ...

s (''ena''). Although the men and women lived separately, they had many interactions. Depending on the village, ''qasgiq'' and ''ena'' were connected by a tunnel. Both qasgiq and ena also served as schools and workshops for young boys and girls. Among the Akulmiut, the residential pattern of separate houses for women and children and a single residence for men and boys persisted until about 1930.

The women's house or Ena ('' a'' sg ''nek'' dual ''net'' pl in Yupʼik, ''ena'' sg ''enet'' pl in Cupʼik, ''ena'' in Cupʼig) was an individual or semi-communal smaller sod house. They looked similar in construction to the qasgiqs but were only about half the size. Women and children lived in houses that served as residences for two to five women and their children. Raising children was the women's responsibility until young boys left the home to join other males in the qasgiq to learn discipline and how to make a living. The ena also served as a school and workshop for young girls, where they could learn the art and craft of skin sewing, food preparation, and other important survival skills.

mask

A mask is an object normally worn on the face, typically for protection, disguise, performance, or entertainment, and often employed for rituals and rites. Masks have been used since antiquity for both ceremonial and practical purposes, ...

making, tool making, and kayak

]

A kayak is a small, narrow human-powered watercraft typically propelled by means of a long, double-bladed paddle. The word ''kayak'' originates from the Inuktitut word '' qajaq'' (). In British English, the kayak is also considered to be ...

construction. It was also a place for learning hunting and fishing skills. At times, the men created a sweatbath, firebath, where hot fires and rocks produced heat to aid in body cleansing. Thus, the qasgiq was a residence, bathhouse, and workshop for all but the youngest male community members who still lived with their mothers. Although there were no formally recognized leaders or offices to be held, men and boys were assigned specific places within the qasgiq that distinguished the rank of males by age and residence. The qasgiq was a ceremonial and spiritual center for the community.

In primary villages, all ceremonies (and Yupʼik dancing) and gatherings (within and between villages among the socio-territorial and neighboring groups) took place in the qasgiq. During the early 20th century, Christian church services were held in the qasgiq before churches were constructed. Virtually all official business, within the group, between groups and villages, and between villagers and non-Yupʼik (such as early missionaries) was conducted in the qasgiq.

The Yupʼik Eskimo did not live in igloo

An igloo (Inuit languages: , Inuktitut syllabics (plural: )), also known as a snow house or snow hut, is a type of shelter built of suitable snow.

Although igloos are often associated with all Inuit, they were traditionally used only by the ...

s or snow houses. But, the northern and northwestern Alaskan Iñupiaq built snow houses for temporary shelter during their winter hunting trips. The word ''iglu'' means "house" in Iñupiaq. This word is the Iñupiaq cognate of the Yupʼik word ''ngel'u'' (" beaver lodge, beaver house"), which it resembled in shape.

Regional groups

Among the Yupʼik of southwestern Alaska, societies (regional or socio-territorial groups), like those of the Iñupiat of northwestern Alaska, were differentiated by territory, speech patterns, clothing details, annual cycles, and ceremonial life. Prior to and during the mid-19th century, the time of Russian exploration and presence in the area, the Yupiit were organized into at least twelve, and perhaps as many as twenty, territorially distinct regional or socio-territorial groups (their native names will generally be found ending in ''-miut'' postbase which signifies "inhabitants of ..." tied together by kinshipFienup-Riordan, 1993, p. 29.Pete, 1993, p. 8.—hence the Yupʼik word ''tungelquqellriit'', meaning "those who share ancestors (are related)".Pete, 1993, p. 8. These groups included: * Unalirmiut (Unaligmiut), inhabiting the Norton Sound area.Fienup-Riordan, 1990, p. 154, "Figure 7.1. Regional groupings for the Yukon-Kuskokwim region, circa 1833."Oswalt, 1967, pp. 5–9. See also Map 2, "Aboriginal Alaskan Eskimo tribes", insert between pp. 6 and 7.Oswalt, 1990, p. ii, "The Kusquqvagmiut area and the surrounding Eskimo and Indian populations" (map). The name derives from the Yupʼik word ''Unaliq'', denoting a Yupʼik from the Norton Sound area, especially the north shore villages of Elim and Golovin and the south shore villages of Unalakleet and St. Michael. Unalirmiut were speakers of the Norton Sound Unaliq subdialect of Yupʼik.Jacobson, 1984. * Pastulirmiut, inhabiting the mouth of the Yukon River. The name derives from ''Pastuliq'', the name of an abandoned village of southernNorton Sound

The Norton Sound ( Inupiaq: ''Imaqpak'') is an inlet of the Bering Sea on the western coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, south of the Seward Peninsula. It is about 240 km (150 mi) long and 200 km (125 mi) wide. The Yukon Riv ...

near the present-day village of Kotlik at one of the mouths of the Yukon River

The Yukon River is a major watercourse of northwestern North America. From its source in British Columbia, it flows through Canada's territory of Yukon (itself named after the river). The lower half of the river continues westward through the U.S ...

. The village name comes from the root ''paste-'' meaning ''to become set in a position'' (for instance, a tree bent by the wind). Pastulirmiut were speakers of the Norton Sound Kotlik subdialect of Yupʼik, and are also called ''pisalriit'' (sing. ''pisalria'') denoting their use of this subdialect in which ''s'' is used in many words where other speakers of Yupʼik use ''y''.

* Kuigpagmiut (Ikogmiut), inhabiting the Lower Yukon River. The name derives from ''Kuigpak'', meaning "big river", the Yupʼik name for the Yukon River

The Yukon River is a major watercourse of northwestern North America. From its source in British Columbia, it flows through Canada's territory of Yukon (itself named after the river). The lower half of the river continues westward through the U.S ...

.

* Marayarmiut (Mararmiut, Maarmiut, Magemiut), inhabiting the Scammon Bay area. The name derives from ''Marayaaq'', the Yupʼik name for Scammon Bay, which in turn derives from ''maraq'', meaning "marshy, muddy lowland". ''Mararmiut'', deriving from the same word, denotes flatland dwellers in general living between the mouth of the Yukon and Nelson Island.

* Askinarmiut, inhabiting the area of the present-day villages of Hooper Bay and Chevak. Askinarmiut is an old name for the village of Hooper Bay. (DCED).

* Qaluyaarmiut (Kaialigamiut, Kayaligmiut), inhabiting Nelson Island. The name derives from ''Qaluyaaq'', the Yupʼik name for Nelson Island, which derives in turn from ''qalu'', meaning "dipnet". In the Qaluuyaaq, there are three villages. Those villages are ''Toksook bay, Nightmute,'' and ''Tununak.''

* Akulmiut, inhabiting the tundra or "Big Lake" area north of the Kuskokwim River. The name denotes people living on the tundra—as opposed to those living along the coastline or major rivers—such as in the present-day villages of Nunapitchuk, Kasigluk, or Atmautluak. The name derives from ''akula'' meaning "midsection", "area between", or "tundra".

* Caninermiut, inhabiting the lower Bering Sea coast on either side of Kuskokwim Bay

Kuskokwim Bay is a bay in southwestern Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside ...

, including the area north of the bay where the modern-day villages of Chefornak, Kipnuk, Kongiganak, Kwigillingok are located and south of the bay where the villages of and Eek and Quinhagak are located (Goodnews Bay?). The name derives from ''canineq'', meaning "lower coast", which derives in turn from the root ''cani'', "area beside".

* Nunivaarmiut (Nuniwarmiut, Nuniwagamiut), inhabiting Nunivak Island. The name derives from ''Nunivaaq'', the name for the island in the General Central dialect of Yupʼik. In the Nunivak dialect of Yupʼik (that is, in Cupʼig), the island's name is ''Nuniwar'' and the people are called ''Nuniwarmiut''.NPT, Inc. (2004-08-24)"We are Cupʼit."

Mekoryuk, AK: Nuniwarmiut Piciryarata Tamaryalkuti (Nunivak Cultural Programs). Retrieved on 2004-04-14. * Kusquqvagmiut (Kuskowagamiut), inhabiting the Lower and middle Kuskokwim River.Branson and Troll, 2006, p. xii. Map 3, "Tribal areas, villages and linguistics around 1818, the time of contact." The name derives from ''Kusquqvak'', the Yupʼik name for the Kuskokwim River, possibly meaning "a big thing (river) with a small flow". The Kusquqvagmiut can be further divided into two groups: ** Unegkumiut, inhabiting the Lower Kuskokwim below

Bethel

Bethel (, "House of El" or "House of God",Bleeker and Widegren, 1988, p. 257. also transliterated ''Beth El'', ''Beth-El'', ''Beit El''; ; ) was an ancient Israelite city and sacred space that is frequently mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

Bet ...

to its mouth in Kuskowkim Bay.Oswalt, 1990, p. 12. The word derives from ''unegkut'', meaning "those downriver"; hence, "downriver people".

** Kiatagmiut, inhabiting inland regions in the upper drainages of the Kuskowkim, Nushagak, Wood

Wood is a structural tissue/material found as xylem in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulosic fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin t ...

, and Kvichak river drainages. The word derives probably from ''kiani'', meaning "inside" or "upriver"; hence, "upriver people". The Kiatagmiut lived inland along the Kuskokwim River drainage from the present location of Bethel

Bethel (, "House of El" or "House of God",Bleeker and Widegren, 1988, p. 257. also transliterated ''Beth El'', ''Beth-El'', ''Beit El''; ; ) was an ancient Israelite city and sacred space that is frequently mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

Bet ...

to present-day Crow Village and the vicinity of the 19th-century Russian outpost Kolmakovskii Redoubt. By the mid-19th century, many Kiatagmiut had migrated to the drainage of the Nushagak River.Oswalt, 1990, pp. 13–14.

* Tuyuryarmiut (Togiagamiut), inhabiting the Togiak River area. The word derives from ''Tuyuryaq'', the Yupʼik name for the village of Togiak.

* Aglurmiut (Aglegmiut), inhabiting the Bristol Bay area along the Lower Nushagak River and the northern Alaska Peninsula. The word derives from ''agluq'', meaning "ridgepole" or "center beam of a structure".

While Yupiit were nomadic, the abundant fish and game of the Y-K Delta and Bering Sea coastal areas permitted for a more settled life than for many of the more northerly Iñupiaq people. Under normal conditions, there was little need for interregional travel, as each regional group had access to enough resources within its own territory to be completely self-sufficient. However, fluctuations in animal populations or weather conditions sometimes necessitated travel and trade between regions.

Economy

Hunting-gathering

The homeland of Yupʼik is the Dfc climate type

The homeland of Yupʼik is the Dfc climate type subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of hemiboreal regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Fennoscandia, Northwestern Russia, Siberia, and the Cair ...

tundra ecosystem. The land is generally flat tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

and wetlands

A wetland is a distinct semi-aquatic ecosystem whose groundcovers are flooded or saturated in water, either permanently, for years or decades, or only seasonally. Flooding results in oxygen-poor ( anoxic) processes taking place, especially ...

. The area covers about 100,000 square miles which are roughly about 1/3 of Alaska.Terryl Miller (2006)Yupʼik (Central Eskimo) Language Guide (and more!), a useful introduction to the Central Eskimo (Yupʼik) Language

World Friendship Publishing, Bethel, Alaska, 2006 Their lands are located in five of the 32

ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) is an ecological and geographic area that exists on multiple different levels, defined by type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of land or water, and c ...

s of Alaska:

Before European contact, the Yupʼik, like other neighboring Indigenous groups, were semi-nomadic hunter-fisher-gatherers who moved seasonally throughout the year within a reasonably well-defined territory to harvest sea and land mammals, fish, bird, berry and other renewable resources. The economy of Yupʼik is a mixed cash-subsistence system, like other modern foraging economies in Alaska. The primary use of wild resources is domestic. Commercial fishing in Alaska and trapping patterns are controlled primarily by external factors.

On the coast, in the past as in the present, to discuss hunting was to begin to define a man. In Yupʼik, the word ''anqun'' (man) comes from the root ''angu-'' (to catch after chasing; to catch something for food) and means, literally, a device for chasing.

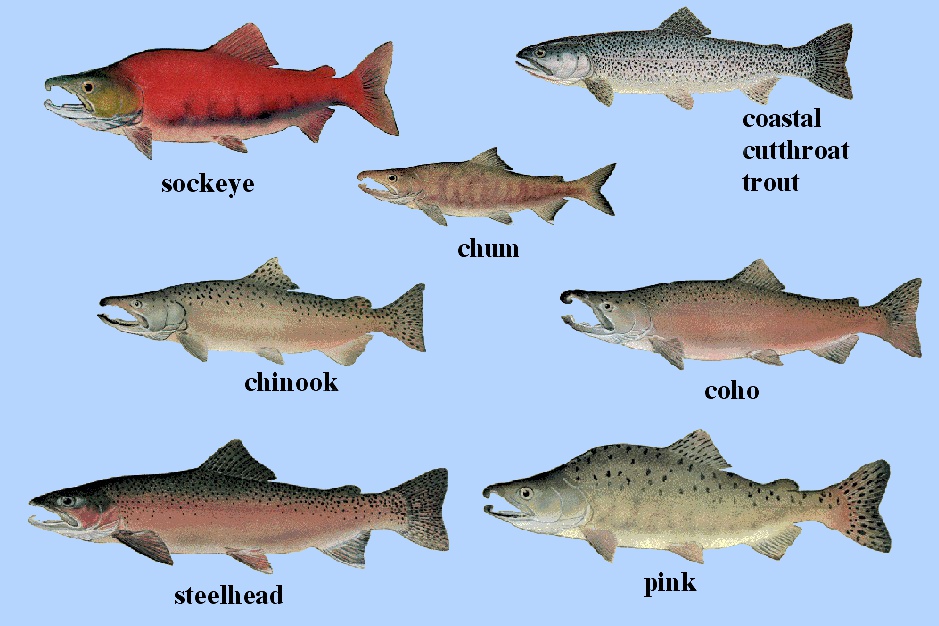

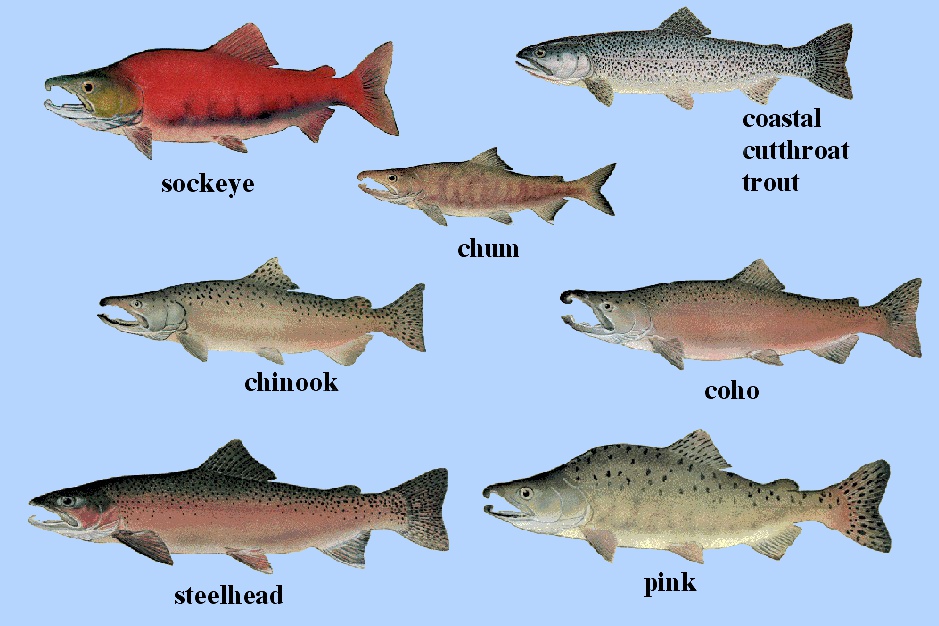

Northwest Alaska is one of the richest Pacific salmon areas in the world, with the world's largest commercial Alaska salmon fishery in Bristol Bay.

Trade

In the Nome Census Area, Brevig Mission, an Iñupiaq community, tended to trade with other Iñupiaq communities to the north: Shishmaref, Kotzebue, and Point Hope. The Yupʼik communities ( Elim, Stebbins and St. Michael), tended to trade with Yupʼik communities to the south: Kotlik, Emmonak, Mountain Village,Pilot Station

A pilot station is an onshore headquarters for maritime pilots, or a place where pilots can be hired from. To get from a pilot station to an approaching ship, pilots need to use fast vessels to arrive in time, i.e. a pilot boat.

History

Histor ...

, St. Mary's of the Kusilvak Census Area.

Transportation

Traditionally,

Traditionally, transportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

was primarily by dog sled

A dog sled or dog sleigh is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow, a practice known as mushing. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for Sled dog racing, dog sl ...

s (land) and kayak

]

A kayak is a small, narrow human-powered watercraft typically propelled by means of a long, double-bladed paddle. The word ''kayak'' originates from the Inuktitut word '' qajaq'' (). In British English, the kayak is also considered to be ...

s (water). Sea mammal hunting and fishing in the Bering Sea region took place from both small narrow closed skin-covered boats called ''kayaks'' and larger broad open skin-covered boats called ''umiaks''. Kayaks were used more frequently than umiaks. Traditionally, kayaking and umiaking served as water transportation and sea hunting. Dog sleds are ideal for land transportation. Pedestrian

A pedestrian is a person traveling on foot, by wheelchair or with other mobility aids. Streets and roads often have a designated footpath for pedestrian traffic, called the '' sidewalk'' in North American English, the ''pavement'' in British En ...