Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of

servants

A domestic worker is a person who works within a residence and performs a variety of household services for an individual, from providing cleaning and household maintenance, or cooking, laundry and ironing, or care for children and elderly d ...

in an

English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in

mid-14th-century England. The 14th century witnessed the rise of the yeoman

longbow archers during the

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

, and the yeoman outlaws celebrated in the

Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary noble outlaw, heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature, theatre, and cinema. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions o ...

ballads. Yeomen joined the English Navy during the Hundred Years' War as

seamen and archers. In the early 15th century, yeoman was the rank of

chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct that developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of ...

between

page

Page most commonly refers to:

* Page (paper), one side of a leaf of paper, as in a book

Page, PAGE, pages, or paging may also refer to:

Roles

* Page (assistance occupation), a professional occupation

* Page (servant), traditionally a young m ...

and

squire. By the late 17th century, yeoman became a rank in the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

for the common seamen who were in charge of ship's stores, such as foodstuffs, gunpowder, and sails.

References to the emerging social stratum of wealthy land-owning commoners began to appear after 1429. In that year, the

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

re-organized the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

into counties and boroughs, with voting rights granted to all

freeholders. The

Electors of Knights of the Shires Act 1429 restricted voting rights to those freeholders whose land value exceeded 40

shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

. These yeomen became a social stratum of commoners below the

landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

, but above the

husbandmen. This stratum later embodied the political and economic ideas of the

English Enlightenment and

Scottish Enlightenment, and transplanted those ideas to

British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

during the

early modern era

The early modern period is a historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There is no exact date ...

.

Numerous yeoman farmers in North America served as citizen soldiers in the

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

during the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. The 19th century saw a revival of interest in the medieval period with

English Romantic literature. The yeoman outlaws of the ballads were refashioned into heroes fighting for justice under the law and the

rights of freeborn Englishmen.

Etymology

The etymology of yeoman is uncertain, for several reasons.

The earliest documented use occurs in

Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

.

There are no known

Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

words which are considered acceptable parent words for yeoman.

Nor are there any readily identifiable

cognates

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

Because language change can have radical effects on both the soun ...

of yeoman in

Anglo-Norman,

Old Frisian

Old Frisian was a West Germanic language spoken between the late 13th century and the end of 16th century. It is the common ancestor of all the modern Frisian languages except for the North Frisian language#Insular North Frisian, Insular North ...

,

Old Dutch

In linguistics, Old Dutch ( Modern Dutch: ') or Old Low Franconian (Modern Dutch: ') is the set of dialects that evolved from Frankish spoken in the Low Countries during the Early Middle Ages, from around the 6th Page 55: "''Uit de zesde eeu ...

,

Old Saxon

Old Saxon (), also known as Old Low German (), was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Eur ...

, or

Middle Low German

Middle Low German is a developmental stage of Low German. It developed from the Old Saxon language in the Middle Ages and has been documented in writing since about 1225–34 (). During the Hanseatic period (from about 1300 to about 1600), Mid ...

.

The four last-named of these languages are

West Germanic languages

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic languages, Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic languages, North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages, East Germ ...

, closely related to Old English at the time they were spoken. Taken together, these facts would indicate that yeoman (1) is a word specific to the

regional dialects found in England; and (2) is nothing similar to any word used in continental Europe.

Another complicating factor for the etymology is that yeoman is a

compound word

In linguistics, a compound is a lexeme (less precisely, a word or Sign language, sign) that consists of more than one Word stem, stem. Compounding, composition or nominal composition is the process of word formation that creates compound lexemes. C ...

made by joining two other words: ''yeo'' + ''man''. Linguists have been perplexed about the origin of ''yeo'' since scholars such as

John Mitchell Kemble and

Joseph Bosworth began the modern linguistic study of Old English in the early to mid 19th century.

Two possible etymologies have been proposed to explain the origin of ''yeo''.

''Oxford English Dictionary''

The ''

Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the principal historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP), a University of Oxford publishing house. The dictionary, which published its first editio ...

'' (OED) has proposed that yeoman is derived from ''yongerman'', which first appeared in a manuscript called ''Pseudo-Cnut's Constitutiones de Foresta''.

Although the manuscript has been demonstrated to be a forgery (it was produced during the reign of

King Henry II of England, rather than during the reign of

King Cnut), it is considered authentic to the 11th and 12th-century

forest laws.

According to the OED,

the manuscript refers to 3 social classes: (1) the

thegn

In later Anglo-Saxon England, a thegn or thane (Latin minister) was an aristocrat who ranked at the third level in lay society, below the king and ealdormen. He had to be a substantial landowner. Thanage refers to the tenure by which lands were ...

(noble) at the top; (2) the tunman (townman) at the bottom; and (3) the lesser thegn in the middle. ''Yongerman'' is considered a

synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

for a lesser thegn. OED suggested that ''yongerman'' is related to ''youngman'', meaning a male youth or young male adult who was in the service of a high-ranking individual or family.

This proposed etymology is that ''youngman'' is in turn related to

Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

''ungmenni'' (youths);

North Frisian ''ongman'' (lad, fellow);

Dutch ''jongeman'' (youngman); and

German ''Jungmann'' (deckhand, ordinary seaman);

cf. also German ''

Junker

Junker (, , , , , , ka, იუნკერი, ) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German , meaning 'young nobleman'Duden; Meaning of Junker, in German/ref> or otherwise 'young lord' (derivation of and ). The term is traditionally ...

'' ⇐ ''jung

rHerr''. This etymology provides a plausible

semantic

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

link from ''yongerman'' to ''youngman'', while at the same time providing most of the earliest definitions of yeoman.

''Chambers Dictionary of Etymology''

The ''Chambers Dictionary of Etymology'' (CDE) is another well-respected scholarly source, as it is published by the same company which produces ''

The Chambers Dictionary

''The Chambers Dictionary'' was first published by William and Robert Chambers as ''Chambers's English Dictionary'' in 1872. It was an expanded version of ''Chambers's Etymological Dictionary'' of 1867, compiled by James Donald. A second editio ...

''. Their proposed etymology reconstructs a possible Old English word, ''*ġēamann'', as the parent of yeoman. (The asterisk or star as the first letter is a linguistic convention to indicate the word has been reconstructed, and is unattested in any surviving record). The reconstructed word is a compound word made from the root word ''ġē'', ''ġēa'' (district, region) + ''mann'' (man). To further strengthen their etymology, CDE compares their reconstructed word to Old Frisian ''gāman'' (villager), and modern

West Frisian ''gea'', ''goa'', Dutch ''gouw'', German ''Gau'' (district, region).

When comparing the simpler and more comprehensive OED etymology with the CDE etymology, modern linguists have expressed dissatisfaction with the CDE version.

Medieval meanings

In the

history of the English language

English language, English is a West Germanic language that originated from North Sea Germanic, Ingvaeonic languages brought to Great Britain, Britain in the mid-5th to 7th centuries AD by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo-Saxon migrants ...

, the earliest recorded usage of yeoman occurs in the

Late Middle English period, and then becoming more widespread in the

Early Modern English

Early Modern English (sometimes abbreviated EModEFor example, or EMnE) or Early New English (ENE) is the stage of the English language from the beginning of the Tudor period to the English Interregnum and Restoration, or from the transit ...

period. The

transition from Middle English to Early Modern English was a gradual process occurring over decades. For the sake of assigning a historical date, OED defines the end of Middle English and the beginning of Early Modern English as occurring in 1500.

The year 1500 marks the end of nearly 200 years of political and economic upheaval in England. The

Hundred Years War, the recurring episodes of the

Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

, and over 32 years of civil war known as the

War of the Roses all contributed to the end of the

Middle Ages in England, and the beginning of the

English Renaissance

The English Renaissance was a Cultural movement, cultural and Art movement, artistic movement in England during the late 15th, 16th and early 17th centuries. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginni ...

. It was during this time that English gradually replaced Norman French as the official language.

The first single-language dictionary of the English language,

Robert Cawdrey's ''

Table Alphabeticall

''A Table Alphabeticall'' is the abbreviated title of the first monolingual dictionary in the English language, created by Robert Cawdrey and first published in London in 1604.

The work is notable for being the first collection of its kind. At ...

'', was published in 1604. The dictionary only included unusual English words, and loan words from foreign languages such as Hebrew, Greek, Latin, or French. Yeoman is not included in this dictionary. This suggests that in 1604, yeoman was a very commonly-used English word.

A more comprehensive, or general dictionary, was published in 1658.

Edward Phillips

Edward Phillips (August 1630 – c. 1696) was an English author.

Life

He was the son of Edward Phillips, of the Crown Office in Chancery, and his wife Anne, only sister of John Milton, the poet. Edward Phillips the younger was born in Stran ...

' ''

The New World of English Words

''The New World of English Words, or, a General Dictionary'' is an English dictionary compiled by Edward Phillips and first published in London in 1658. It was the first folio English dictionary.

Contents

As well as containing common words, th ...

'' contained basic definitions.

Yeoman is included; probably for the first time in an English language dictionary. But only a legal definition was given: (1) a social class immediately below a Gentleman; and (2) a freeborn man who can sell "his own free land in yearly revenue to the summe of 40 shillings Sterling".

The fact that only the legal definition (introduced in the

Electors of Knights of the Shires Act 1429) was given is another suggestion that yeoman was a common word at the time.

Between the 12th century ''Pseudo-Cnut de Foresta'' and ''The New World of English Words'' in 1658, linguists have had to re-construct the meanings of yeoman from the surviving manuscripts. The various meanings of yeoman were apparently widely understood by the document author and his audience, and were not explained in the manuscripts. Linguists have deduced these specific historical meanings based on the context in which yeoman was used within the document itself.

It is these meanings which are described in the following sections.

Household attendant or servant (14th century-present)

Yeoman, as a household servant, is one of the earliest documented uses of the word. During the 14th century, it referred to a servant or attendant in a

royal or noble household, usually one who was of higher rank in the

household hierarchy. This hierarchy reflected the

feudal society in which they lived. Everyone who served a royal or noble household knew their duties, and knew their place. This was especially important when the household staff consisted of both nobles and commoners. There were actually two household hierarchies which existed in parallel. One was the organization based upon the function (

duty

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; , past participle of ; , whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may arise from a system of ethics or morality, e ...

) being performed. The other was based upon whether the person performing the duty was a noble or a commoner.

Similar household duties were grouped into

Household Offices, which were then assigned to one of several Chief Officers. In each Household Office, the servants were organized into a hierarchy, arranged in ranks according to the level of responsibility.

;

Sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

: The highest rank, which reported directly to the Chief Officer and oversaw an individual Household Office. The word was introduced to England by the Normans, and meant an attendant or servant.

; Yeoman

: The middle rank of the Household Office.

; Groom

: The lowest rank of the Household Office. It generally referred to a menial position for a free-born commoner.

The Chief Officers were nobles, but the servant ranks of Sergeant, Yeoman, and Groom

could be filled by either commoners or members of noble families. Any household duties which required close contact with the lord's immediate family, or their rooms, were handled by nobles.

For example, the

Steward oversaw the Offices concerned with household management. Procurement, storage, and preparation of food, waiting at table, and tending to the kitchen gardens, were some of the duties for which the Steward was responsible. Under the Steward during the reign of King Edward III, there were two separate groups of yeomen: ''Yeomen of the King's Chamber'' and ''Yeomen of the Offices''. The first group were members of noble families who waited only on the King, and the second group were commoners who performed similar duties for other household residents and guests in the Great Hall, kitchen, pantry, and other areas.

Yeoman service

Yeoman service (also yeoman's service) is an

idiom

An idiom is a phrase or expression that largely or exclusively carries a Literal and figurative language, figurative or non-literal meaning (linguistic), meaning, rather than making any literal sense. Categorized as formulaic speech, formulaic ...

which means "good, efficient, and useful service" in some cause.

It has the

connotations

A connotation is a commonly understood culture, cultural or emotional association that any given word or phrase carries, in addition to its explicit or Literal and figurative language, literal meaning (philosophy of language), meaning, which is it ...

of the work performed by a faithful servant of the lower ranks, who does whatever it takes to get the job done.

The sense – although not the use – of the idiom can be found in the ''

Gest of Robyn Hode'', dated to about 1500. In the ''First Fitte'' (the first section of the ballad),

Robin gives money to a poor knight to pay his debt to the abbot of St Mary's Abbey. Noticing that the knight was traveling alone, Robin offers him the service of Little John as a yeoman:

Here Robin vouches

for Little John as a yeoman, a faithful servant who will perform whatever duties are required in times of great need.

The phrase ''yeoman's service'' is used by

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

in ''

Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

'' (published in 1601). In act V, scene 2,

Prince Hamlet

Prince Hamlet is the title character and protagonist of William Shakespeare's tragedy ''Hamlet'' (1599–1601). He is the Prince of Denmark, nephew of the usurping King Claudius, Claudius, and son of King Hamlet, the previous King of Denmark. At ...

tells

Horatio how he discovered the king's plot against himself in a commission (document). Hamlet then says he has substituted for the original a commission which he himself wrote:

Hamlet remarks that he "wrote it fair", that is, in elegant, gentlemanly prose; a style of writing which he tried very hard to forget. But in composing the fake commission, Hamlet had to resort to "that learning". He tells Horatio that "it did me yeoman's service", that is, his learning stood him in good stead. ''Standing one in good stead'' is another idiom very similar in meaning to yeoman service.

Note that it was used in the third line of Stanza of the ''Gest of Robyn Hode'' quoted in the paragraph above.

Attendant or assistant to an official (ca 14th–17th centuries)

Marshalsea Court was a court of the English royal household, presided over by the Steward and the

Knight-Marshal. The court kept records from about 1276 until 1611. Unfortunately, only a few survive from the years 1316–59.

[ Some information on the yeomen of the Marshalsea Court can be found in the Household Ordinance of King Edward IV from about 1483. The author of the Ordinance, looking back to the earlier household ordinances of King Edward III wrote: "Our sovereign lord's household is now discharged ... of the Court of Marshalsea, and all his clerks and yeomen." The writer was referring to the transfer of the Marshalsea Court from the royal household.

The Ordinance describe the duties of the Steward of the Household, who was also the Steward of the Court of Marshalsea. The Steward was assigned one chaplain, two squires, and four yeomen as his personal retinue. One yeoman was specifically attached to the Steward's rooms at the Court of Marshalsea "to keep his chamber and stuff". When the Steward was present in Court, he was entitled to a 10-person retinue. Besides the Steward and the Knight-Marshal, two other members of the royal household were empowered to preside: the Treasurer and the Controller. Of the Steward, Treasurer, and the Controller, at least one of them must preside in the Court every day.

]

A chivalric rank

One of the earliest documents which contains yeoman as a chivalric rank is the ''Chronicon Vilodunense'' (''Life of Saint Edith''). Originally written in Latin by Goscelin sometime in the 11th century, it was later translated into the Wiltshire dialect of Middle English about 1420. Part of the manuscript relates a story about the

One of the earliest documents which contains yeoman as a chivalric rank is the ''Chronicon Vilodunense'' (''Life of Saint Edith''). Originally written in Latin by Goscelin sometime in the 11th century, it was later translated into the Wiltshire dialect of Middle English about 1420. Part of the manuscript relates a story about the archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

caught in a storm at sea while on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He prayed to Saint Edith for the storm to subside, and suddenly he saw Saint Edith standing beside him. The Blessed Virgin had sent her, she said, to assure the archbishop he would arrive home safe and sound. Miraculously, the storm stopped. The archbishop kept his vow, and visited St Edith's tomb at Wilton Abbey. There he preached a sermon about the miracle to each man there: knight, squire, yeoman, and page.

Although Wilton Abbey was a Benedictine nunnery

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican Comm ...

, it held its lands from the king by knight service

Knight-service was a form of feudal land tenure under which a knight held a fief or estate of land termed a knight's fee (''fee'' being synonymous with ''fief'') from an overlord conditional on him as a tenant performing military service for his ...

. The Abbess

An abbess (Latin: ''abbatissa'') is the female superior of a community of nuns in an abbey.

Description

In the Catholic Church (both the Latin Church and Eastern Catholic), Eastern Orthodox, Coptic, Lutheran and Anglican abbeys, the mod ...

' knights were her tenants, who in turn held land from the Abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christians, Christian monks and nun ...

by knight service. Usually the abbess fulfilled her duty to the king by scutage

Scutage was a medieval English tax levied on holders of a knight's fee under the feudal land tenure of knight-service. Under feudalism the king, through his vassals, provided land to knights for their support. The knights owed the king militar ...

. But she had knights with King Henry III on his 1223 Welsh campaign, and at the Siege of Bedford Castle

Bedford Castle was a large medieval castle in Bedford, England. Built after 1100 by Henry I of England, Henry I, the castle played a prominent part in both the civil war of the Anarchy and the First Barons' War. The castle was significantly ex ...

the following year. Between 1277 and 1327 she offered knight service at least four times.[

About 50 years later in 1470, another reference to yeomen is made in the Warkworth Chronicle. The scene is King Edward IV's coronation, and the chronicler lists the nobles who received titles from His Majesty. At the end of the list he notes: "And other gentlemen and yeomen he made knights and squires, as they had deserved." (modern spelling) The chronicler makes no further mention of these men.

]

Yeomanry (14th–15th centuries)

An early historical meaning that seems to have disappeared before our modern era is "something pertaining to or characteristic of a yeoman", such as the speech or the dress.[ Robin demands a one penny toll of the Potter, for which the traveler could then proceed unharmed by the outlaw. The Potter refuses to pay. A scuffle ensues, in which the Potter overcomes Robin. The Potter then wants to know whom he has beaten. After hearing Robin's name, the Potter responds (modern translation from glossary notes):

In the first stanza the Potter describes himself as a poor yeoman, whom people say Robin Hood would never stop or waylay (also known as a holdup). It is obvious from the story that the Potter was not dressed in a yeomanly manner, otherwise Robin would have never accosted him. It was not until Robin heard the Potter speak that he recognizes him as a yeoman. Whether he was referring to his direct straightforward manner, or his dialect, or both, is unclear to a 21st-century reader. But it is apparent that the original 15th century audiences knew exactly what ''good yeomanry'' was.

]

Yeoman archer (14th–15th centuries)

The Yeoman Archer is a term applied specifically to English and Welsh military longbow archers (either mounted or on foot) of the 14th–15th centuries. Yeoman archers were commoners; free-born members of the social classes below the

The Yeoman Archer is a term applied specifically to English and Welsh military longbow archers (either mounted or on foot) of the 14th–15th centuries. Yeoman archers were commoners; free-born members of the social classes below the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

and gentry

Gentry (from Old French , from ) are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past. ''Gentry'', in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to Landed property, landed es ...

. They were a product of the English form of feudalism in which the military duty of a knight to his lord (which was implicit in tenure

Tenure is a type of academic appointment that protects its holder from being fired or laid off except for cause, or under extraordinary circumstances such as financial exigency or program discontinuation. Academic tenure originated in the United ...

feudalism) was replaced by paid, short-term service.

The Yeoman Archers were the English Army's response to a chronic manpower problem when trying to field an army on the European continent during the 14th century. Against 27,000 French knights, England could only muster at most 5,000 men-at-arms

A man-at-arms was a soldier of the High Medieval to Renaissance periods who was typically well-versed in the use of arms and served as a fully-armoured heavy cavalryman. A man-at-arms could be a knight, or other nobleman, a member of a kni ...

. With this 5:1 tactical disadvantage, the English needed a strategic advantage.

When Edward I invaded Wales in 1282, he quickly realized the battlefield importance of the opposing Welsh archers. Firing from ambush, they inflicted serious casualties on Edward's army. When Edward invaded Scotland for the second time in 1298, his army consisted mostly of infantry (12,500 of 15,000 men).Battle of Falkirk

The Battle of Falkirk (; ), on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence. Led by Edward I of England, King Edward I of England, the English army defeated the Scottish people, Scots, led by William Wal ...

, the English army archers opened up the Scottish schiltrons with hails of arrows. The Scottish infantrymen fled the battlefield, to be pursued and killed by the English cavalry.[

] In 1333, his grandson, Edward III, undertook his first invasion of Scotland, which culminated with the Battle of Halidon Hill.Battle of Crécy

The Battle of Crécy took place on 26 August 1346 in northern France between a French army commanded by King PhilipVI and an English army led by King Edward III. The French attacked the English while they were traversing northern France ...

was followed by another victory at the Battle of Poitiers

The Battle of Poitiers was fought on 19September 1356 between a Kingdom of France, French army commanded by King John II of France, King JohnII and an Kingdom of England, Anglo-Gascony, Gascon force under Edward the Black Prince, Edward, the ...

, and a final victory at the Siege of Calais. After the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected victory of the vastly outnumbered English troops agains ...

, the Yeoman Archer had become as legendary as his bow. By negating the tactical advantage of large numbers of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

(mounted knights and men-at-arms) with their ability to rapidly fire volleys of arrows, Yeoman Archers are considered part of the Infantry revolution of the 14th century. They could be deployed as "Archers on horse" (mounted archers who could reach the scene quickly, dismount, & set up a firing line) or as "Archers on foot" (foot archers who followed as reinforcements).

Yeoman of the Guard (15th century-present)

On 22 August 1485, near the small village of Stoke Golding, Henry Tudor met

On 22 August 1485, near the small village of Stoke Golding, Henry Tudor met King Richard III

Richard III (2 October 1452 – 22 August 1485) was King of England from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the Plantagenet dynasty and its cadet branch the House of York. His defeat and death at the Battle of Boswor ...

in battle for the Crown of England. The War of the Roses had persisted intermittently for more than 30 years between the rival claimants of the House of York

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York ...

(white rose) and the House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancasterfrom which the house was namedfor his second son Edmund Crouchback in 1267 ...

(red rose). In 1483, Richard, of the House of York, had deposed his young nephew, 12-year old Edward V

Edward V (2 November 1470 – ) was King of England from 9 April to 25 June 1483. He succeeded his father, Edward IV, upon the latter's death. Edward V was never crowned, and his brief reign was dominated by the influence of his uncle and Lord ...

. Henry Tudor, of the House of Lancaster, was the favored candidate to replace Richard.[

Three armies met that day on Bosworth Field: Richard, with his supporters, ]Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The premier non-royal peer, the Duke of Norfolk is additionally the premier duke and earl in the English peerage. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the t ...

and the Earl of Northumberland

The title of Earl of Northumberland has been created several times in the Peerage of England and of Great Britain, succeeding the title Earl of Northumbria. Its most famous holders are the House of Percy (''alias'' Perci), who were the most po ...

; Henry, with his troops under command of the veteran John de Vere, Earl of Oxford; and the troops of Thomas, Lord Stanley. Stanley was a powerful lord in northwest England. But he was stepfather of Henry Tudor, and Richard was holding his son hostage. Stanley's forces remained uncommitted as the battle raged. As Oxford advanced, the troops appeared to leave Henry, his bodyguards, and some French mercenaries isolated. Or so it appeared to Richard. Sensing an opportunity, Richard charged toward Henry. Seeing this, Stanley made his decision, and charged to reinforce Henry. Henry's bodyguards fought bravely to hold off Richard's bodyguards until the arrival of Stanley's troops. During the melee

A melee ( or ) is a confused hand-to-hand combat, hand-to-hand fight among several people. The English term ''melee'' originated circa 1648 from the French word ' (), derived from the Old French ''mesler'', from which '':wikt:medley, medley'' and ...

, Richard's horse became mired in the marsh, and he was killed. Henry had won.[

Henry rewarded his bodyguards by formal establishing the ''Yeomen of the Guard of (the body of) our Lord the King''. The King of England always had bodyguards (''Yeoman of the Crown''). This royal act recognized their bravery and loyalty in doing their duty, and designated them as the first members of a bodyguard to protect the King (or Queen) of England forever. In their first official act on 1 October 1485, fifty members of the Yeoman of the Guard, led by John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, formally escorted Henry Tudor to his coronation ceremony.

]

Yeoman Warder (16th century-present)

The Tower of London was used as permanent royal residence until 1509–10, during the reign of King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

. Henry ordered 12 Yeoman of the Guard to remain as a garrison, indicating that the Tower was still a royal palace. When the Tower no longer served that function, the garrison became warders, and were not permitted to wear the Yeoman of the Guard uniform. During the reign of Henry's son, Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

, the warders were given back the uniform. This was done as a result of petition from the former Lord Protector of the Realm, Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp (150022 January 1552) was an English nobleman and politician who served as Lord Protector of England from 1547 to 1549 during the minority of his nephew King E ...

. Seymour, who was Edward's uncle, had been confined there, and found the warders to be most considerate.

English Navy yeoman (to 1485)

The earliest documented use of yeoman relative to a navy is found in the ''Merchant's Tale of Beryn'': "Why gone the yeomen to boat – Anchors to haul?" The context of the quotation sheds no further light on either yeomen or boats. What is important is the date of the manuscript: between 1450 and 1470.[ This places the ''Merchant's Tale of Beryn'' about the same time as the '' Robin Hood and the Monk'' manuscript, and shortly before the end of the Hundred Years War. To understand the connections between yeoman and the early English navy, it is necessary to examine King Edward III's reign and the beginning of the Hundred Years War.

England did not have a standing navy until the Tudor Navy of ]King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

. Before then, the "King's Ships" were a very small fleet allocated for the King's personal use. During the Hundred Years War, King Edward III actually owned only a few ships. The rest were made available to the King through agreements with his nobles and the various port towns of England. About 25 ships of various sizes were made available to Edward III every year. They ranged from the small Thames sailing barge

A Thames sailing barge is a type of commercial sailing boat once common on the River Thames in London. The flat-bottomed barges, with a shallow draught and leeboards, were perfectly adapted to the Thames Estuary, with its shallow waters and na ...

s (descended from the famous Norman longship

Longships, a type of specialised Viking ship, Scandinavian warships, have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven and documented from at least the fourth century BC. Originally invented and used by th ...

s of the Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidery, embroidered cloth nearly long and tall that depicts the events leading up to the Norman Conquest, Norman Conquest of England in 1066, led by William the Conqueror, William, Duke of Normandy challenging H ...

) which shuttled the royal retinue up and down the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

, to large cogs. Cogs were large merchant ships, with high prow

The bow () is the forward part of the hull (watercraft), hull of a ship or boat, the point that is usually most forward when the vessel is underway. The aft end of the boat is the stern.

Prow may be used as a synonym for bow or it may mean the f ...

s and stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

s, and a single mast with a single square sail. The largest cogs were built to carry sizable wine cask

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids ...

s. The Vintners' Company, in return for their monopoly on the wine trade, had to make their cogs available to the King on demand.

The 1345 ''Household Ordinance of Edward III'' provides a brief summary of the Fleets organized for the Crécy campaign. The South Fleet (which included all English ports south and west of River Thames) consisted of 493 ships with 9,630 mariners. Of these, the ''King's Ships'' (25 ships with 419 mariners), the ports of Dartmouth (31 ships with 757 mariners), Plymouth (26 ships with 603 mariners), and London (25 ships with 602 mariners) were the largest contingents. The North Fleet (which included all English ports north of River Thames) consisted of 217 ships with 4521 mariners. The port of Yarmouth, with 43 ships with 1095 mariners, was the largest contingent. The definition of a mariner is unclear, as is the difference between a mariner and a sailor. The number of mariners given is about twice that needed to man a ship. Edward's warships carried two crews. The second crew was used for night sailing, for providing a crew for prize ships, and for providing more fighting men.

Early in the Hundred Years War, the largest existing merchant ships, such as the cog, were converted to warships with the addition of wooden castles. There were three types of castles:

Early in the Hundred Years War, the largest existing merchant ships, such as the cog, were converted to warships with the addition of wooden castles. There were three types of castles: forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

(at the prow), aftcastle (at the stern), and the topcastle (at the top of the mast). A record from 1335 tells of the vessel ''Trinity'' (200 tons) being converted for war. As new ships were built, the castles became integral with the ship's hull.

As the King was impressing all the big ships and their crews for the war effort, the mayors and merchants of the port towns were retrofitting old ships and building new ones for harbor defense, and patrols to protect coastal ships and fishing boats from enemy ships and pirates.

By this time (mid-14th century), the Captain of the ship was a separate military rank. He was responsible for the defense of the ship. For every 4 mariners aboard the warship, there was 1 man-at-arms and 1 archer who was stationed in the castles. For a vessel the size of the ''Trinity'', which carried about 130 mariners, there were at least 32 men-at-arms and 32 archers.

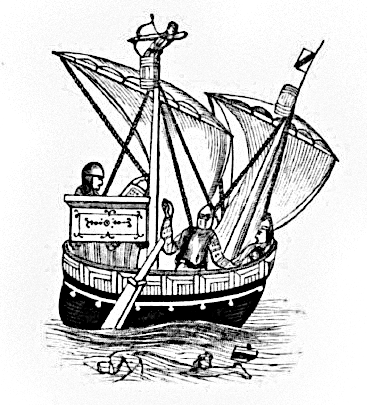

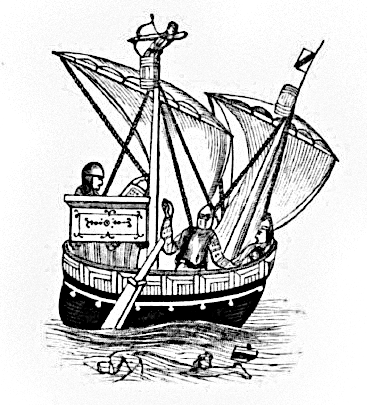

These illuminations from a 14th-century manuscript provide some insight as to how the retrofitted castles were used in battle. The first illustration shows a 2-masted vessel, with a man-at-arms in the retrofitted aftcastle, and an archer in the retrofitted topcastle.

These illuminations from a 14th-century manuscript provide some insight as to how the retrofitted castles were used in battle. The first illustration shows a 2-masted vessel, with a man-at-arms in the retrofitted aftcastle, and an archer in the retrofitted topcastle.

The next illustration shows a battle scene. The tactics included using grappling hooks to position the ships so that the archers on the aftcastles had clear shots into the opposing ship. After raking the deck with arrows, the men-at-arms would swing over to finish the job.

The warship Captain was also responsible for convoying 30 merchant vessels from English ports to the French shore. These vessels carried the troops, horses, food, forage, and whatever else was needed upon landing in France.

The Master (or Master Mariner) was responsible for sailing the vessel. Under him were the Constables (equivalent to today's

The next illustration shows a battle scene. The tactics included using grappling hooks to position the ships so that the archers on the aftcastles had clear shots into the opposing ship. After raking the deck with arrows, the men-at-arms would swing over to finish the job.

The warship Captain was also responsible for convoying 30 merchant vessels from English ports to the French shore. These vessels carried the troops, horses, food, forage, and whatever else was needed upon landing in France.

The Master (or Master Mariner) was responsible for sailing the vessel. Under him were the Constables (equivalent to today's boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, or the third hand on a fishing vessel, is the most senior Naval rating, rate of the deck department and is responsible for the ...

s). One constable oversaw twenty crewmen. Collecting a crew was traditionally the task of the Master. However, with the need for double-crews, the King authorized his Admirals to offer the King's pardon to outlaws and pirates. In 1342, the number of men who responded exceeded the demand. Edward's deputies never had trouble again raising the crews they needed.[ This is reminiscent of the pardons offered by Edward to outlaws of the Robin Hood ballads. Therefore, it is possible that the real answer to "Why gone the yeomen to boat – Anchors to haul?" was a pardon.

Instances of yeoman in a naval context are rare before 1700. In 1509, the Office of Ordnance had a Master, Clerk, and Yeoman.][ In 1608, a House of Lords manuscript mentions a ship's gunner and a yeoman.][(modern spelling) In 1702, actual titles of seamen appear in the '']London Gazette

London is the capital and largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Western Europe, with a population of 14.9 million. London stands on the River Tha ...

'': Yeomen of the Sheets, and Yeomen of the Powder Room.

Social stratum of small freeholders

This review of the yeoman freeholders is divided into three periods: (a) up to 1500; (b) between 1500 and 1600; and (c) between 1600 and 1800. This division corresponds roughly to the historical changes experienced by the freeholders themselves, as well as the shifting contemporary social hierarchies in which they lived. It is also influenced by the availability of sources for each period.

Up to 1500

The parliament of 1327 was a watershed event. For the first time since the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

, an English king was disposed peaceably, and not usurped by military means. Although Edward II had been previously threatened with deposition in 1310 and 1321, all those who attended the parliament of 1327 were aware of the constitutional crisis. The king was imprisoned by his Queen Isabella and her paramour Roger Mortimer after their invasion of England. The Parliament was a legal pretense to confer legitimacy upon their actions. The Lords Temporal

The Lords Temporal are secular members of the House of Lords, the upper house of the British Parliament. These can be either life peers or hereditary peers, although the hereditary right to sit in the House of Lords was abolished for all but n ...

and the Lords Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who sit in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. Up to 26 of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not including retired bish ...

were summoned in the King's name, while the Knights of the Shire

Knight of the shire () was the formal title for a member of parliament (MP) representing a county constituency in the British House of Commons, from its origins in the medieval Parliament of England until the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885 en ...

, Burgesses from the towns, and representatives from the Cinque Ports

The confederation of Cinque Ports ( ) is a historic group of coastal towns in south-east England – predominantly in Kent and Sussex, with one outlier (Brightlingsea) in Essex. The name is Old French, meaning "five harbours", and alludes to ...

were elected to attend. According to Michael Prestwich: "What was necessary was to ensure that every conceivable means of removing the King was adopted, and the procedures combined all possible precedents". Hence, establishing the legitimacy of Edward III was paramount. But it was the Knights of the Shire and Burgesses (hereafter referred to as ''the commons'') who drove the proceedings, both before and after Edward III's coronation.[ Beginning in 1327, the commons became a permanent part of parliament.

] In the 14th century, the name commons did not have its modern meaning of ''common people''. It referred to ''the communities'', which was ''les Communs'' in

In the 14th century, the name commons did not have its modern meaning of ''common people''. It referred to ''the communities'', which was ''les Communs'' in Anglo-Norman French

Anglo-Norman (; ), also known as Anglo-Norman French, was a dialect of Old Norman that was used in England and, to a lesser extent, other places in Great Britain and Ireland during the Anglo-Norman period.

Origin

The term "Anglo-Norman" har ...

. The word meant that those elected to the parliament were representatives of their communities, that is, the shires and the urban areas.clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

as members of the sessions. In 1333, the commons sat together in a single chamber for the first time. About this same time, the commons was evolving into its role of legislating taxation. The king preferred to include taxes on clerical income with the direct taxes on the laity

In religious organizations, the laity () — individually a layperson, layman or laywoman — consists of all Church membership, members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-Ordination, ordained members of religious orders, e ...

. The church hierarchy (archbishops and bishops) considered that no secular authority had the right to enforce tax collection from clerical income in a secular court. Such cases, they thought, should be considered in an of law. In 1340, the bishops negotiated a settlement with the Crown, wherein disputes between the king and clergy over taxation would be heard in ecclesiastical courts at either Canterbury or York. Therefore, there was no longer a need for the proctors to attend the commons. This was an important milestone for the commons. It became a secular assembly, its deliberations unaffected by ecclesiastical concerns. In 1342, the commons reorganized itself as the House of Commons, deliberating separately from the king, nobles and higher clergy of noble status. Each county had two Knights of the Shire as representatives, except for Durham and Cheshire, which were county palatine

In England, Wales and Ireland a county palatine or palatinate was an area ruled by a hereditary nobleman enjoying special authority and autonomy from the rest of a kingdom. The name derives from the Latin adjective ''palātīnus'', "relating t ...

s.

Initially, the Knights of the Shire were selected from among the belted knights.Landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

, but above, say, a husbandman". Often it was hard to distinguish minor landed gentry from the wealthier yeomen, and wealthier husbandmen from the poorer yeomen.

1500–1600

As some yeomen overlapped into the newly emerging gentry through wealth and marriage; others merged with the merchants and professions of the towns through education; some became local officials in the counties; and still others maintained their original identity as farmers.

Yeomen were often constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. ''Constable'' is commonly the rank of an officer within a police service. Other peo ...

s of their parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

, and sometimes chief constables of the district, shire

Shire () is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries. It is generally synonymous with county (such as Cheshire and Worcestershire). British counties are among the oldes ...

or hundred

100 or one hundred (Roman numerals, Roman numeral: C) is the natural number following 99 (number), 99 and preceding 101 (number), 101.

In mathematics

100 is the square of 10 (number), 10 (in scientific notation it is written as 102). The standar ...

. Many yeomen held the positions of bailiff

A bailiff is a manager, overseer or custodian – a legal officer to whom some degree of authority or jurisdiction is given. There are different kinds, and their offices and scope of duties vary.

Another official sometimes referred to as a '' ...

s for the High Sheriff or for the shire or hundred. Other civic duties would include churchwarden, bridge warden, and other warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically ident ...

duties. It was also common for a yeoman to be an overseer for his parish. Yeomen, whether working for a lord, king, shire, knight, district or parish, served in localised or municipal police forces raised by or led by the landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

. Some of these roles, in particular those of constable and bailiff

A bailiff is a manager, overseer or custodian – a legal officer to whom some degree of authority or jurisdiction is given. There are different kinds, and their offices and scope of duties vary.

Another official sometimes referred to as a '' ...

, were carried down through families. Yeomen often filled ranging, roaming, surveying, and policing roles. In districts remoter from landed gentry and burgesses, yeomen held more official power: this is attested in statutes of the reign of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

(reigned 1509–1547), indicating yeomen along with knights and squires as leaders for certain purposes.

Yeoman farmer

In the United States, yeomen were identified in the 18th and 19th centuries as non-slaveholding, small landowning, family farmers. In areas of the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

where land was poor, like East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 coun ...

, the landowning yeomen were typically subsistence farmers

Subsistence agriculture occurs when farmers grow crops on smallholdings to meet the needs of themselves and their families. Subsistence agriculturalists target farm output for survival and for mostly local requirements. Planting decisions occu ...

, but some managed to grow crop

A crop is a plant that can be grown and harvested extensively for profit or subsistence. In other words, a crop is a plant or plant product that is grown for a specific purpose such as food, Fiber, fibre, or fuel.

When plants of the same spe ...

s for market. Whether they engaged in subsistence or commercial agriculture, they controlled far more modest landholdings than those of the planters, typically in the range of 50–200 acres. In the Northern United States, practically all the farm

A farm (also called an agricultural holding) is an area of land that is devoted primarily to agricultural processes with the primary objective of producing food and other crops; it is the basic facility in food production. The name is used fo ...

s were operated by yeoman farmers as family farms.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

was a leading advocate of the yeomen, arguing that the independent farmers formed the basis of republican values. Indeed, Jeffersonian Democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, wh ...

as a political force was largely built around the yeomen. After the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

(1861–1865), organizations of farmers, especially the Grange, formed to organize and enhance the status of the yeoman farmers.[Thomas A. Woods, ''Knights of the Plow: Oliver H. Kelley and the Origins of the Grange in Republican Ideology'' (2002)]

Modern meanings

The Yeomanry

During the 1790s, the threat of French invasion of Great Britain appeared genuine.[ In 1794, The British Volunteer Corps was organized for home defense, composed of local companies of part-time volunteers.][ Their cavalry troops became known as the Yeomanry Cavalry.][ The infantry companies were disbanded by 1813, as the threat of ]Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's invasion evaporated. However, the Yeomanry Cavalry was retained. They were used to quell the food riots of 1794–95 and break up workers' strikes during the 1820s–1840s, as part of their mandate was to maintain the King's Peace. The rise of civilian police forces during this same period (the Metropolitan Police Act 1829

The Metropolitan Police Act 1829 ( 10 Geo. 4. c. 44) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and ...

, the Municipal Corporations Act 1835

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 ( 5 & 6 Will. 4. c. 76), sometimes known as the Municipal Reform Act, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in the incorporated boroughs of England and Wales. The le ...

, and the County Police Act 1839) replaced the Yeomanry Cavalry as an instrument of law enforcement. In 1899, the Yeomanry Cavalry were deployed overseas during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, after a series of devastating British Army defeats. In 1901, the Yeomanry Cavalry formed the nucleus of the new Imperial Yeomanry. Eight years later, the Imperial Yeomanry and the Volunteer Force were combined as the Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry in ...

.[

]

United States Navy

In the modern Navy, a yeoman is an enlisted service member who performs administrative and clerical work.

The Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United Colonies and United States from 1775 to 1785. It was founded on October 13, 1775 by the Continental Congress to fight against British forces and their allies as part of the American Revolutionary ...

was established by the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

in 1775. The legislation called for officers, warrant officers, and enlisted men.[ The roster of enlisted men was left open to each ship captain to fill as he deemed necessary. After the Treaty of Paris, the Navy was considered unnecessary by Congress, and it was disbanded in 1785. The surviving ships were sold off.

The ]US Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally including seven articles, the Constitut ...

(Article I, Section 8, Clause 14) granted the new US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

the power to build and maintain a navy. It wasn't until 1794, when the worsening US relations with Great Britain and France, as well as the continuing attacks by Barbary pirates, forced Congress to appropriate funds to construct 6 frigates

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

. The US naval hierarchy established followed the precedent set by the British Royal Navy. To which the US Navy added Petty Officers, which included the jobs traditionally assigned to naval yeomen. The first US Navy yeomen were ''Yeoman of the Gunroom'' and the ''Captain's Clerk''. Petty officers were appointed by the ship's captain, and served at his pleasure. They did not retain their rank when they moved to another ship.[

As the US Navy transformed from sail to steam, and from wood to steel, the yeoman's duties gradually changed to more administrative tasks. The ''Gunner's Yeoman'' was eliminated in 1838, the ''Boatswain's Yeoman'' in 1864, the ''Engineer's Yeoman'' and the ''Equipment Yeoman'' in 1893. The ''Captain's Clerk'' of 1798 became a Yeoman in 1893.][ Which makes today's Yeoman a descendant of one of the original rates and ratings in the US Navy.

]

Yeomen in Late Middle/Early Modern English literature

Until the 16th century, yeomen were mentioned either as servants in Norman French-speaking aristocratic households, or as members of the English army or navy in the Anglo-Norman kings' military expeditions across the English Channel. It was not until Middle English became England's official language during the 14th century and the new social stratum of yeoman freeholders gained respectability during the 15th century, that the oral ballads repeated by previous generations of English-speaking yeomen were written down and distributed to a wider audience.

The best-known ballads were about the yeoman outlaw Robyn Hode (Robin Hood, in modern spelling). A J Pollard, in his book ''Imagining Robin Hood: The Late Medieval Stories in Historical Context'', proposed that the first Robin Hood was a literary fiction of the 15th and early 16th centuries. This does not mean that Pollard claims that Robin Hood was ''not'' historical. He considers that what modern popular culture ''thinks'' it knows about Robin is actually based upon how previous generations over the last 500 years have viewed him. The historical Robyn Hode was (or were, in the case of there possibly being several men whose exploits were melded into the single individual of the ballads) is of secondary importance to his cultural symbolism for succeeding generations. In his review of Pollard's book,[ Thomas Ohlgren,][ one of the editors of the University of Rochester's ''The Robin Hood Project'',][ agreed with this assessment. Because ''A Gest of Robyn Hode'' is a 16th-century collective memory of a fictional past, it can also be seen as a reflection of the century in which it was written. Following in the footsteps of Pollard and Ohlgren, this section examines some of the literature written in Late Middle English and Early Modern English to explore how the historical Yeoman was slowly transformed by succeeding generations into a legend for their own times.

]

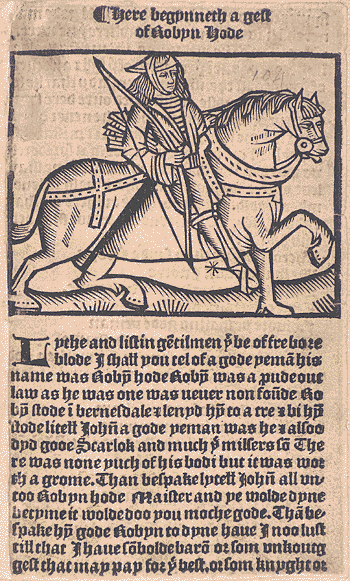

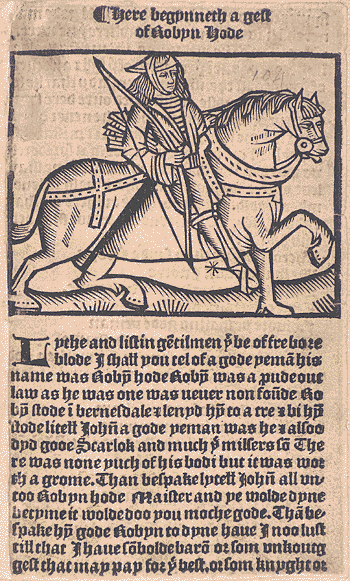

''A Gest of Robyn Hode''

Rhymes ( ballads) of Robin Hood were being sung as early as the 1370s.

Rhymes ( ballads) of Robin Hood were being sung as early as the 1370s. William Langland

William Langland (; ; ) is the presumed author of a work of Middle English alliterative verse generally known as ''Piers Plowman'', an allegory with a complex variety of religious themes. The poem translated the language and concepts of the cl ...

, the author of ''Piers Plowman

''Piers Plowman'' (written 1370–86; possibly ) or ''Visio Willelmi de Petro Ploughman'' (''William's Vision of Piers Plowman'') is a Middle English allegorical narrative poem by William Langland. It is written in un-rhymed, alliterative ...

'', has Sloth say that he does not know his '' Pater Noster'' (Latin for the '' Our Father'' prayer) as perfectly as the priest sings it, but he does know the rhymes of Robin Hood.[ Unfortunately, the rhymes that William Langland heard have not survived. The earliest surviving ballads are '' Robin Hood and the Monk'' (dated to 1450),][ '' Robin Hood and the Potter'' (dated to about 1500),][ and ''A Gest of Robyn Hode''.][

The oldest copies of ''A Gest of Robyn Hode'' are print editions dated between 1510 and 1530.][ These early rhymes are witnesses to a crucial time in English history. The 14th–15th centuries saw the rise of the common people's Middle English over the decline of the aristocrats' ]Norman French

Norman or Norman French (, , Guernésiais: , Jèrriais: ) is a '' langue d'oïl'' spoken in the historical and cultural region of Normandy.

The name "Norman French" is sometimes also used to describe the administrative languages of '' Angl ...

, the military prowess of the yeoman longbowmen during the Hundred Years War (see Yeoman Archers), and the beginnings of a yeoman class (see Social Class of Small Freeholders).

In the ''Gest'', Robin is an outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them. ...

(meaning "outside the law"); someone who was summoned to a law court, but failed to appear. He has gathered around himself a fellowship of "sevenscore men", that is, 140 skilled bowmen. Nevertheless, Robin is the King's Man: "I love no man in all the world/So well as I do my king;". Disguised as a monk carrying the King's Seal, King Edward finally meets Robin, and is invited to a feast. During the archery contest afterwards, Robin suddenly recognizes Edward. He immediately kneels to offer homage, asking for mercy for his men. Edward grants pardon, and invites Robin to court. Robin agrees, and offers his men as a retinue. Note how Robin's behavior fits a commander of men. This entire scene is reminiscent of the contracted indenture offered by Edward III, where pardons were granted for war service (see Yeoman Archers). It is interesting that this historical detail had been preserved in the ''Gest of Robyn Hode''.

These earliest ballads contain clues to the changes in the English social structure which elevated the yeoman to a more powerful and influential level (see A Chivalric Rank). In the box to the left is the opening of ''Robin Hood and the Potter''. (Note that all quotations have modern spelling, and obsolete words have been substituted.) The audience is addressed as "good yeomen", and yeoman Robin is described as possessing the " knightly virtues" of courtesy (good manners), goodness, generosity, and a devotion to the Virgin Mary

Marian devotions are external pious practices directed to the person of Mary, mother of Jesus, by members of certain Christian traditions. They are performed in Catholicism, High Church Lutheranism, Anglo-Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy and Orie ...

. Thomas Ohlgren, a Robin Hood scholar, considers this to be an indication of the social changes the yeomen were undergoing.[ The yeomen may be lower in social rank to the knight, but they see themselves as possessing the traits of the knightly class.

In the box to the right, the opening lines of ''Gest of Robyn Hode'' offer confirmation that yeomen now consider themselves as part of the gentry. The audience is now composed of "gentlemen". Stephen Knight and Thomas Ohlgren suggest that the "Gest" audience was a literate audience interested in political resistance.][ This interpretation appears to be supported by the rise of the new social class of yeoman (see Social Class of Small Freeholders).

]

Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales''

Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' () is a collection of 24 stories written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. The book presents the tales, which are mostly written in verse, as part of a fictional storytelling contest held ...

include several characters described as yeoman, shedding light on the nature of the yeoman in the late 14th century when the work was written.

General Prologue: The Yeoman

In the ''General Prologue'', Chaucer describes The Yeoman as being the only servant The Knight wanted on the pilgrimage. From the way he was dressed, Chaucer supposes he is a

In the ''General Prologue'', Chaucer describes The Yeoman as being the only servant The Knight wanted on the pilgrimage. From the way he was dressed, Chaucer supposes he is a forester

A forester is a person who practises forest management and forestry, the science, art, and profession of managing forests. Foresters engage in a broad range of activities including ecological restoration and management of protected areas. Fores ...

. The man is wearing a green tunic

A tunic is a garment for the torso, usually simple in style, reaching from the shoulders to a length somewhere between the hips and the ankles. It might have arm-sleeves, either short or full-length. Most forms have no fastenings. The name deri ...

and hood. His hair is closely cropped, his face is tanned and weather-beaten, and his horn is slung from a green baldric

A baldric (also baldrick, bawdrick, bauldrick as well as other rare or obsolete variations) is a belt worn over one shoulder that is typically used to carry a weapon (usually a sword) or other implement such as a bugle or drum. The word m ...

. The Yeoman is well-armed. He carries a "mighty bow" in his hand with a sheaf of arrows hung from his belt. Chaucer points out that the peacock feather fletching was well-made. The archer obviously took great care when making his arrows. He also carries a sword, a buckler, and a small dagger. (Note the similarity between this yeoman's accoutrements and those of the ''Yeomen of the King's Crown''.) The forester's final protection is a medal of Saint Christopher

Saint Christopher (, , ; ) is venerated by several Christian denominations. According to these traditions, he was a martyr killed in the reign of the 3rd-century Roman Empire, Roman emperor Decius (), or alternatively under the emperor Maximin ...

, the patron saint of travelers.

Chaucer's description of a forester is based upon his experiences as a deputy forester of North Petherton Park in Somersetshire.

The very first line of The Yeoman's description is the statement the Knight wanted no other servant. Kenneth J Thompson quoted Earle Birney as saying that a forester was the only attendant the Knight needed; he was a "huntsman-forester, knight's bodyguard, squire's attendant, lord's retainer, king's foot-soldier". The forester's job was to protect the ''vert and venison''[ – the deer and the ]Royal forest

A royal forest, occasionally known as a kingswood (), is an area of land with different definitions in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The term ''forest'' in the ordinary modern understanding refers to an area of wooded land; however, the ...

they inhabited. The foresters not only discouraged poaching

Poaching is the illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights.

Poaching was once performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and to supplement meager diets. It was set against the huntin ...

, but provided winter feed, and cared for newly born calves. The medieval English foresters also provided basic woodland management

Forest management is a branch of forestry concerned with overall administrative, legal, economic, and social aspects, as well as scientific and technical aspects, such as silviculture, forest protection, and forest regulation. This includes man ...

by preventing unauthorized grazing, and illegal logging. Another function of the forester was assist the King's Huntsmen in planning the royal hunts. The foresters knew the game animals, and where to find them.

When his lord was campaigning in wartime, the forester was capable of providing additional meat for the lord's table. During the 1358–60 campaign in France, Edward III had 30 falconers on horseback, and 60 couples (or pairs) of hounds.

The Yeoman has his "mighty bow" (most probably a longbow) at the ready, implying he is on duty serving as bodyguard against highwaymen and robbers. He carries a sheaf of arrows under his belt, which implies an arrow bag suspended from his belt.

Chaucer's description of The Yeoman has been interpreted as an iconographic representation of the dutiful servant, diligent and always ready to serve. In other words, the very picture of yeoman service.