Winfield Scott on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

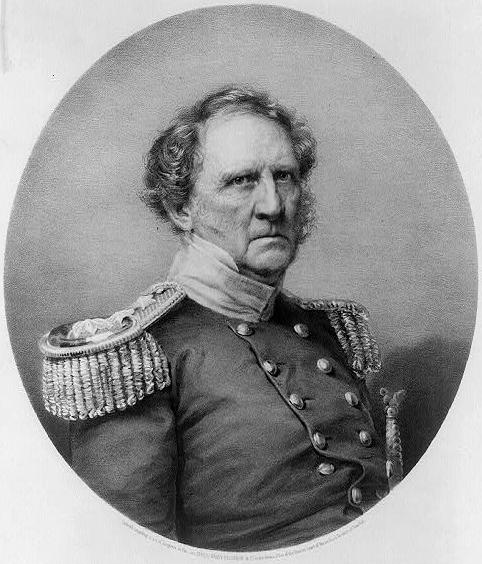

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the

Winfield Scott was born on June 13, 1786, the fifth child of Ann Mason and her husband, William Scott, a planter, veteran of the

Winfield Scott was born on June 13, 1786, the fifth child of Ann Mason and her husband, William Scott, a planter, veteran of the

Tensions between Britain and the United States continued to rise as Britain attacked American shipping, impressed American sailors, and encouraged Native American resistance to American settlement. In July 1812, Congress

Tensions between Britain and the United States continued to rise as Britain attacked American shipping, impressed American sailors, and encouraged Native American resistance to American settlement. In July 1812, Congress  In October 1812, Van Rensselaer's force attacked British forces in the Battle of Queenston Heights. Scott led an artillery bombardment that supported an American crossing of the Niagara River, and he took command of American forces at Queenston after Colonel

In October 1812, Van Rensselaer's force attacked British forces in the Battle of Queenston Heights. Scott led an artillery bombardment that supported an American crossing of the Niagara River, and he took command of American forces at Queenston after Colonel

In March 1817, Scott married Maria DeHart Mayo (1789–1862). She was the daughter of Abigail (

In March 1817, Scott married Maria DeHart Mayo (1789–1862). She was the daughter of Abigail (

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson ordered Scott to

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson ordered Scott to

In the mid-1830s, Scott joined the Whig Party, which was established by opponents of President Jackson. Scott's success in preventing war with Canada under Van Buren confirmed his popularity with the broad public, and in early 1839 newspapers began to mention him as a candidate for the presidential nomination at the 1839 Whig National Convention. By the time of the convention in December 1839, party leader Henry Clay and 1836 presidential candidate

In the mid-1830s, Scott joined the Whig Party, which was established by opponents of President Jackson. Scott's success in preventing war with Canada under Van Buren confirmed his popularity with the broad public, and in early 1839 newspapers began to mention him as a candidate for the presidential nomination at the 1839 Whig National Convention. By the time of the convention in December 1839, party leader Henry Clay and 1836 presidential candidate

On June 25, 1841, Macomb died, and Scott and Gaines were still the two most obvious choices for the position of

On June 25, 1841, Macomb died, and Scott and Gaines were still the two most obvious choices for the position of

Polk and Scott had never liked one another, and their distrust deepened after Polk became president, partly due to Scott's affiliation with the Whig Party. Polk came into office with two major foreign policy goals: the acquisition of Oregon Country, which was under joint American and British rule, and the acquisition of

Polk and Scott had never liked one another, and their distrust deepened after Polk became president, partly due to Scott's affiliation with the Whig Party. Polk came into office with two major foreign policy goals: the acquisition of Oregon Country, which was under joint American and British rule, and the acquisition of

Taylor won several victories against the Mexican army, but Polk eventually came to the conclusion that merely occupying Northern Mexico would not compel Mexico to surrender. Scott drew up an invasion plan that would begin with a naval assault on the

Taylor won several victories against the Mexican army, but Polk eventually came to the conclusion that merely occupying Northern Mexico would not compel Mexico to surrender. Scott drew up an invasion plan that would begin with a naval assault on the

Scott was again a contender for the Whig presidential nomination in the 1848 election. Clay,

Scott was again a contender for the Whig presidential nomination in the 1848 election. Clay,

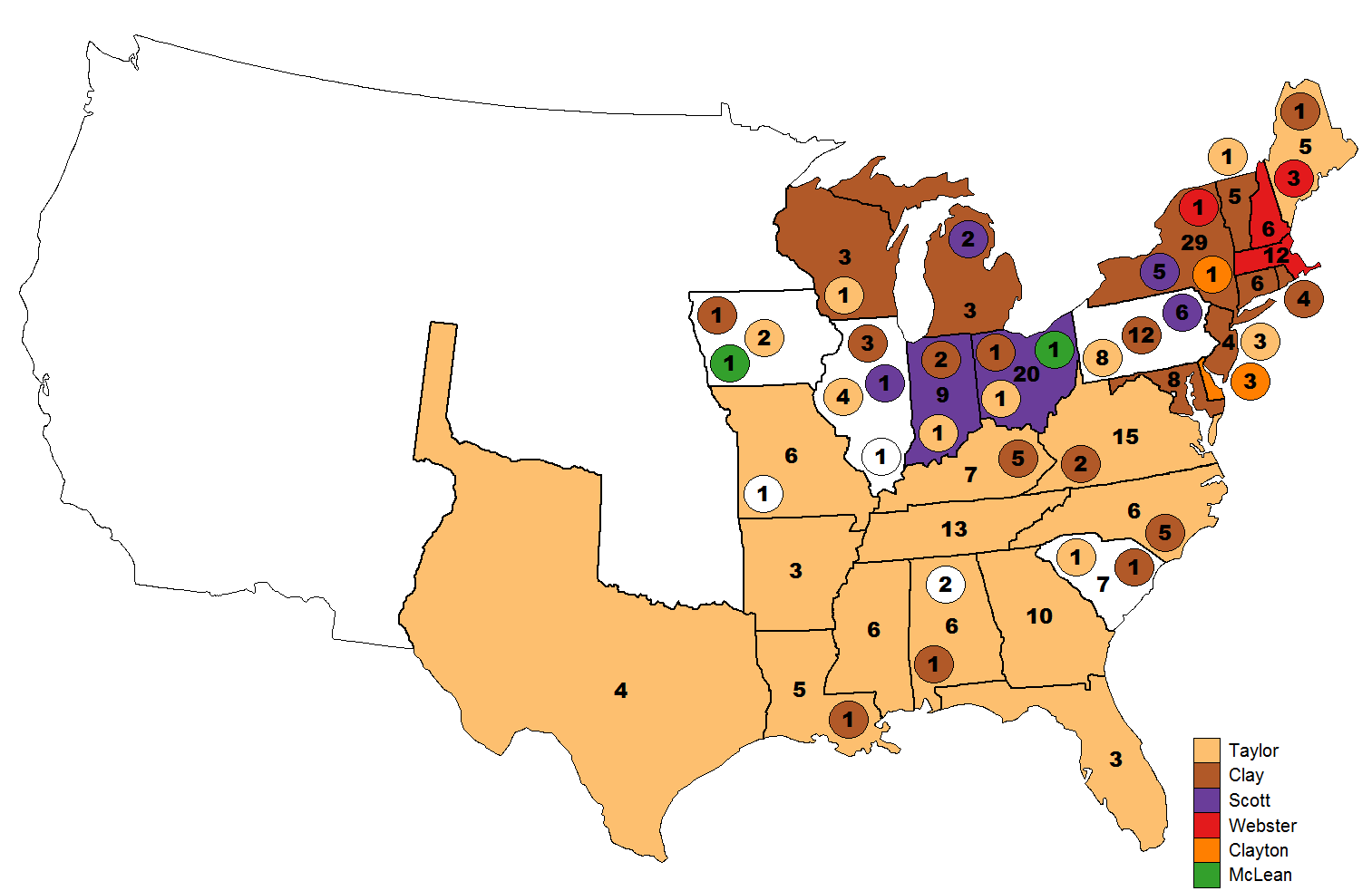

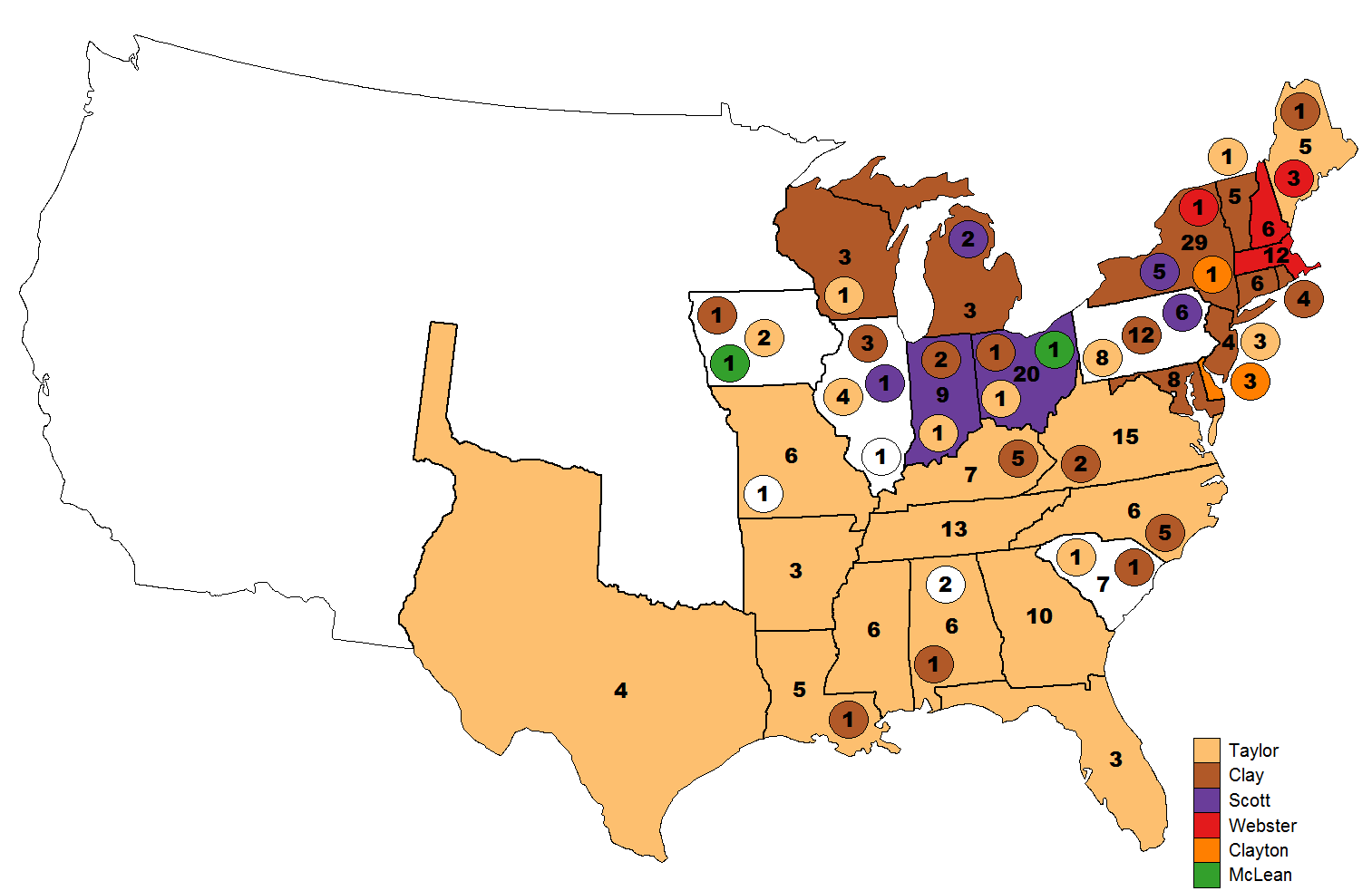

By early 1852, the three leading candidates for the Whig presidential nomination were Scott, who was backed by anti-Compromise Northern Whigs; President Fillmore, the first choice of most Southern Whigs; and Secretary of State Webster, whose support was concentrated in New England. The 1852 Whig National Convention convened on June 16, and Southern delegates won approval of a

By early 1852, the three leading candidates for the Whig presidential nomination were Scott, who was backed by anti-Compromise Northern Whigs; President Fillmore, the first choice of most Southern Whigs; and Secretary of State Webster, whose support was concentrated in New England. The 1852 Whig National Convention convened on June 16, and Southern delegates won approval of a

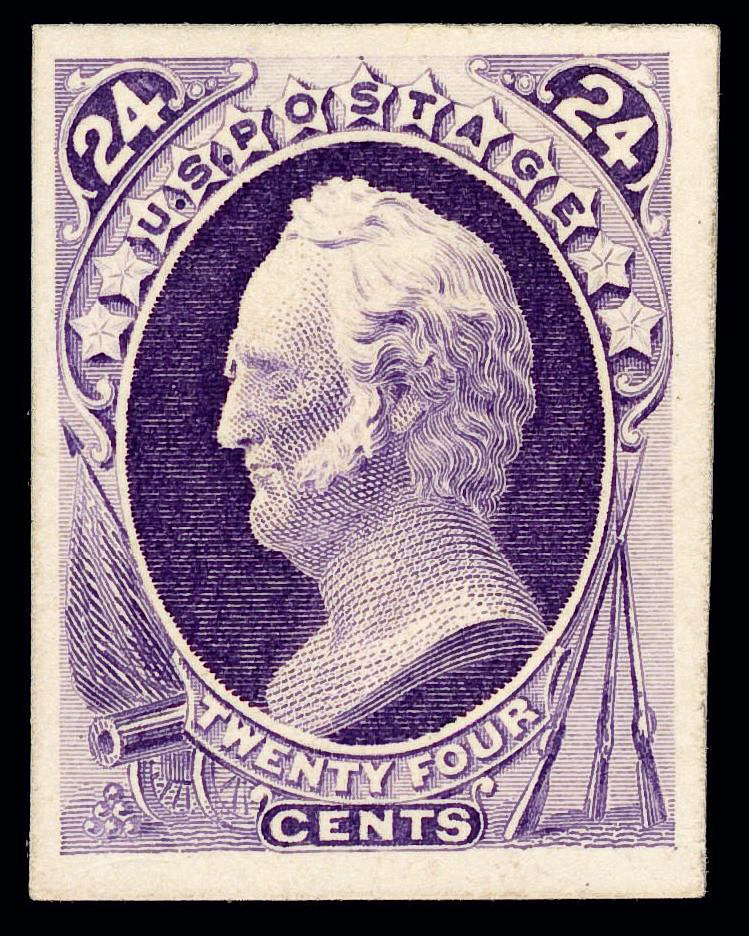

After the 1852 election, Scott continued his duties as the senior officer of the army. He maintained cordial relations with President Pierce but frequently clashed with Pierce's Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, over issues like travel expenses. Despite his defeat in the 1852 presidential election, Scott remained broadly popular, and on Pierce's recommendation, in 1855 Congress passed a resolution promoting Scott to brevet lieutenant general. Scott was the

After the 1852 election, Scott continued his duties as the senior officer of the army. He maintained cordial relations with President Pierce but frequently clashed with Pierce's Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, over issues like travel expenses. Despite his defeat in the 1852 presidential election, Scott remained broadly popular, and on Pierce's recommendation, in 1855 Congress passed a resolution promoting Scott to brevet lieutenant general. Scott was the

By the time Lincoln assumed office, seven states had declared their secession and had seized federal property within their bounds, but the United States retained control of the military installations at Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens. Scott advised evacuating the forts on the grounds that an attempted re-supply would inflame tensions with the South, and that Confederate shore batteries made re-supply impossible. Lincoln rejected the advice and chose to re-supply the forts; although Scott accepted the orders, his resistance to the re-supply mission, along with poor health, undermined his status within the administration. Nonetheless, he remained a key military adviser and administrator. On April 12, Confederate forces began an attack on Fort Sumter, forcing its surrender the following day. On April 15, Lincoln declared that a state of rebellion existed and called up tens of thousands of militiamen. On the advice of Scott, Lincoln offered Robert E. Lee command of the

By the time Lincoln assumed office, seven states had declared their secession and had seized federal property within their bounds, but the United States retained control of the military installations at Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens. Scott advised evacuating the forts on the grounds that an attempted re-supply would inflame tensions with the South, and that Confederate shore batteries made re-supply impossible. Lincoln rejected the advice and chose to re-supply the forts; although Scott accepted the orders, his resistance to the re-supply mission, along with poor health, undermined his status within the administration. Nonetheless, he remained a key military adviser and administrator. On April 12, Confederate forces began an attack on Fort Sumter, forcing its surrender the following day. On April 15, Lincoln declared that a state of rebellion existed and called up tens of thousands of militiamen. On the advice of Scott, Lincoln offered Robert E. Lee command of the  Scott took charge of molding Union military personnel into a cohesive fighting force. Lincoln rejected Scott's proposal to build up the regular army, and the administration would largely rely on volunteers to fight the war. Scott developed a strategy, later known as the

Scott took charge of molding Union military personnel into a cohesive fighting force. Lincoln rejected Scott's proposal to build up the regular army, and the administration would largely rely on volunteers to fight the war. Scott developed a strategy, later known as the

Scott grew very heavy in his last years of service, and was unable to mount a horse or walk more than a few paces without stopping to rest. He was often in ill health, and suffered from

Scott grew very heavy in his last years of service, and was unable to mount a horse or walk more than a few paces without stopping to rest. He was often in ill health, and suffered from

Scott holds the record for the greatest length of active service as general in the U.S. Army, as well as the longest tenure as the army's chief officer. Steven Malanga of ''

Scott holds the record for the greatest length of active service as general in the U.S. Army, as well as the longest tenure as the army's chief officer. Steven Malanga of ''

Scott has been memorialized in numerous ways.

Scott has been memorialized in numerous ways.

Vol. II

an

Vol. III

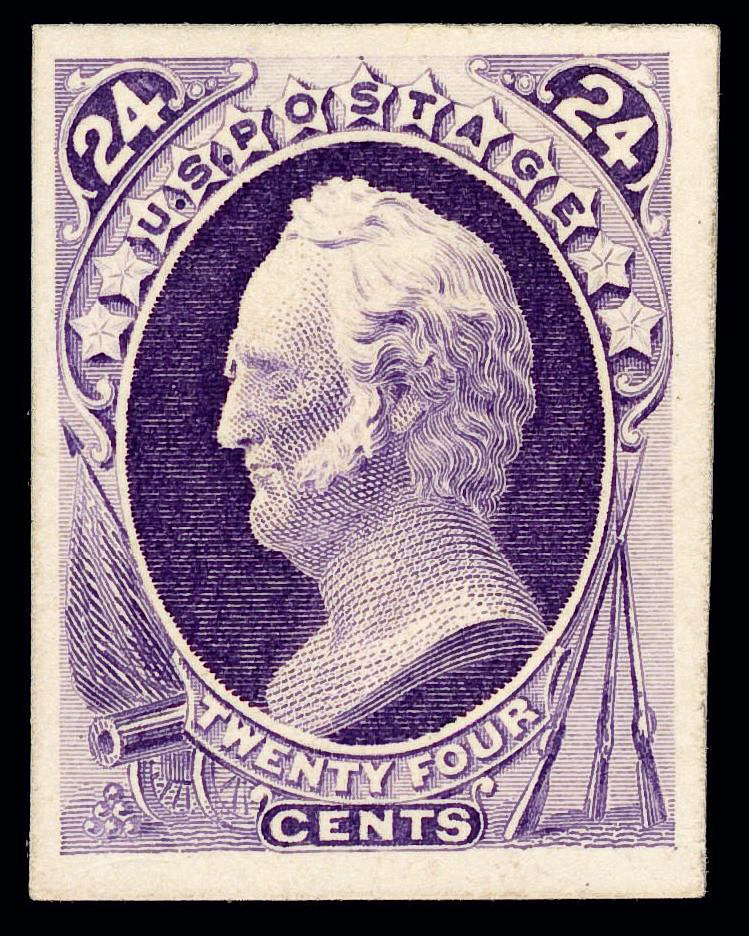

Portrait of General Winfield Scott (1786-1866)

at

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, the early stages of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

and conflicts

Conflict may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Conflict'' (1921 film), an American silent film directed by Stuart Paton

* ''Conflict'' (1936 film), an American boxing film starring John Wayne

* ''Conflict'' (1937 film) ...

with Native Americans. Scott was the Whig Party's presidential nominee in the 1852 election, but was defeated by Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Franklin Pierce. He was known as Old Fuss and Feathers for his insistence on proper military etiquette, as well as the Grand Old Man of the Army for his many years of service.

Scott was born near Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Econ ...

, in 1786. After training as a lawyer and brief militia service, he joined the army in 1808 as a captain of the light artillery. In the War of 1812, Scott served on the Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

front, taking part in the Battle of Queenston Heights and the Battle of Fort George, and was promoted to brigadier general in early 1814. He served with distinction in the Battle of Chippawa, but was badly wounded in the subsequent Battle of Lundy's Lane. After the conclusion of the war, Scott was assigned to command army forces in a district containing much of the Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

, and he and his family made their home near New York City. During the 1830s, Scott negotiated an end to the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", crosse ...

, took part in the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans and ...

and the Creek War of 1836

The Creek War of 1836, also known as the Second Creek War or Creek Alabama Uprising, was a conflict in Alabama at the time of Indian Removal between the Muscogee Creek people and non-native land speculators and squatters.

Although the Creek ...

, and presided over the forced removal of the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

. Scott also helped to avert war with Britain, defusing tensions arising from the Patriot War

The Patriot War was a conflict along the Canada–United States border in which bands of raiders attacked the British colony of Upper Canada more than a dozen times between December 1837 and December 1838. This so-called war was not a conflic ...

and the Aroostook War

The Aroostook War (sometimes called the Pork and Beans WarLe Duc, Thomas (1947). The Maine Frontier and the Northeastern Boundary Controversy. ''The American Historical Review'' Vol. 53, No. 1 (Oct., 1947), pp. 30–41), or the Madawaska War, wa ...

.

In 1841, Scott became the Commanding General of the United States Army

The Commanding General of the United States Army was the title given to the service chief and highest-ranking officer of the United States Army (and its predecessor the Continental Army), prior to the establishment of the Chief of Staff of the ...

, beating out his rival Edmund P. Gaines

Edmund Pendleton Gaines (March 20, 1777 – June 6, 1849) was a career United States Army officer who served for nearly fifty years, and attained the rank of major general by brevet. He was one of the Army's senior commanders during its format ...

for the position. After the outbreak of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

in 1846, Scott was relegated to an administrative role, but in 1847 he led a campaign against the Mexican capital of Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

. After capturing the port city of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, he defeated Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

's armies at the Battles of Cerro Gordo, Contreras, and Churubusco. He then captured Mexico City, after which he maintained order in the Mexican capital and indirectly helped envoy Nicholas Trist

Nicholas Philip Trist (June 2, 1800 – February 11, 1874) was an American lawyer, diplomat, planter, and businessman. Even though he was dismissed by President James K. Polk as the negotiator with the Mexican government, he negotiated the Treat ...

negotiate the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

, which brought an end to the war.

Scott unsuccessfully sought the Whig presidential nomination three times, in 1840, 1844, and 1848. He finally won it in 1852, when the party was already dying off. The Whigs were badly divided over the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

, and Franklin Pierce won a decisive victory over his former commander. Nonetheless, Scott remained popular among the public, and in 1855 he received a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

promotion to the rank of lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

, becoming the first U.S. Army officer to hold that rank since George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

. In 1859 he peacefully solved the conflict of the Pig War, ending the last one in a long series of British-American border conflicts. Despite being a Virginia native, Scott stayed loyal to the Union when the Civil War broke out and served as an important adviser to President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

during the opening stages of the war. He developed a strategy known as the Anaconda Plan

The Anaconda Plan is the name applied to a strategy outlined by the Union Army for suppressing the Confederacy at the beginning of the American Civil War. Proposed by Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, the plan emphasized a Union blockade ...

, but retired in late 1861 after Lincoln increasingly relied on General George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

for military advice and leadership. In retirement, he lived in West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

, where he died on May 29, 1866. Scott's military talent was highly regarded by contemporaries, and historians generally consider him to be one of the most accomplished generals in U.S. history.

Early life

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, and officer in the Dinwiddie County militia. At the time, the Scott family resided at Laurel Hill, a plantation near Petersburg, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. Ann Mason Scott was the daughter of Daniel Mason and Elizabeth Winfield, and Scott's parents chose his maternal grandmother's surname for his first name. Scott's paternal grandfather, James Scott, had migrated from Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

after the defeat of Charles Edward Stuart's forces in the Battle of Culloden. Scott's father died when Scott was six years old; his mother did not remarry. She raised Scott, his older brother James, and their sisters Mary, Rebecca, Elizabeth, and Martha until her death in 1803. Although Scott's family held considerable wealth, most of the family fortune went to James, who inherited the plantation. At six feet, five inches tall and 230 pounds, with a hardy constitution, in his prime Scott was a physically large and imposing figure.

Scott's education included attendance at schools run by James Hargrave and James Ogilvie. In 1805, Scott began attending the College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William III ...

, but he soon left in order to study law in the office of attorney David Robinson. His contemporaries in Robinson's office included Thomas Ruffin

Thomas Ruffin (1787–1870) was an American jurist and justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court from 1829 to 1852 and again from 1858 to 1859. He was chief justice of that Court from 1833 to 1852.

Biography

Thomas Ruffin was born on November ...

. While apprenticing under Robinson, Scott attended the trial of Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

, who had been accused of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

for his role in events now known as the Burr conspiracy

The Burr conspiracy was a plot alleged to have been planned by Aaron Burr in the years during and after his term as Vice President of the United States under US President Thomas Jefferson. According to the accusations against Burr, he attempted to ...

. During the trial, Scott developed a negative opinion of the Senior Officer of the United States Army

The Commanding General of the United States Army was the title given to the service chief and highest-ranking officer of the United States Army (and its predecessor the Continental Army), prior to the establishment of the Chief of Staff of the ...

, General James Wilkinson, as the result of Wilkinson's efforts to minimize his complicity in Burr's actions by providing forged evidence and false, self-serving testimony.

Scott was admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in 1806, and practiced in Dinwiddie. In 1807, Scott gained his initial military experience as a corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non ...

of cavalry in the Virginia Militia, serving in the midst of the ''Chesapeake–Leopard'' affair. Scott led a detachment that captured eight British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

sailors who had attempted to land in order to purchase provisions. Virginia authorities did not approve of this action, fearing it might spark a wider conflict, and they soon ordered the release of the prisoners. Later that year, Scott attempted to establish a legal practice in South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, but was unable to obtain a law license because he did not meet the state's one-year residency requirement.

Early career, 1807–1815

First years in the army

In early 1808, PresidentThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

asked Congress to authorize an expansion of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

after the British announced an escalation of their naval blockade of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, thereby threatening American shipping. Scott convinced family friend William Branch Giles

William Branch Giles (August 12, 1762December 4, 1830; the ''g'' is pronounced like a ''j'') was an American statesman, long-term Senator from Virginia, and the 24th Governor of Virginia. He served in the House of Representatives from 1790 to 1 ...

to help him obtain a commission in the newly expanded army. In May 1808, shortly before his twenty-second birthday, Scott was commissioned as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the light artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

. Tasked with recruiting a company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of people, whether Natural person, natural, Legal person, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common p ...

, he raised his troops from the Petersburg and Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

areas, and then traveled with his unit to New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

to join their Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

. Scott was deeply disturbed by what he viewed as the unprofessionalism of the army, which at the time consisted of just 2,700 officers and men. He later wrote that "the old officers had, very generally, sunk into either sloth, ignorance, or habits of intemperate drinking."

He soon clashed with his commander, General James Wilkinson, over Wilkinson's refusal to follow the orders of Secretary of War William Eustis

William Eustis (June 10, 1753 – February 6, 1825) was an early American physician, politician, and statesman from Massachusetts. Trained in medicine, he served as a military surgeon during the American Revolutionary War, notably at the Bat ...

to remove troops from an unhealthy bivouac site. Wilkinson owned the site, and while the poor location caused several illnesses and deaths among his soldiers, Wilkinson refused to relocate them because he personally profited. In addition, staying near New Orleans enabled Wilkinson to pursue his private business interests and continue the courtship of Celestine Trudeau, whom he later married.

Scott briefly resigned his commission over his dissatisfaction with Wilkinson, but before his resignation had been accepted, he withdrew it and returned to the army. In January 1810, Scott was convicted in a court-martial, partly for making disrespectful comments about Wilkinson's integrity, and partly because of a $50 shortage in the $400 account he had been provided to conduct recruiting duty in Virginia after being commissioned. With respect to the money, the court-martial members concluded that Scott had not been intentionally dishonest, but had failed to keep accurate records. His commission was suspended for one year. After the trial, Scott fought a duel with William Upshaw, an army medical officer and Wilkinson friend whom Scott blamed for initiating the court-martial. Each fired at the other, but both emerged unharmed.

After the duel, Scott returned to Virginia, where he spent the year studying military tactics and strategy, and practicing law in partnership with Benjamin Watkins Leigh

Benjamin Watkins Leigh (June 18, 1781February 2, 1849) was an American lawyer and politician from Richmond, Virginia. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates and represented Virginia in the United States Senate.

Early and family life

Benja ...

. Meanwhile, Wilkinson was removed from command for insubordination, and was succeeded by General Wade Hampton Wade Hampton may refer to the following people:

People

* Wade Hampton I (1752–1835), American soldier in Revolutionary War and War of 1812 and U.S. congressman

*Wade Hampton II (1791–1858), American plantation owner and soldier in War of 1812

* ...

. The rousing reception Scott received from his army peers as he began his suspension led him to believe that most officers approved of his anti-Wilkinson comments, at least tacitly; their high opinion of him, coupled with Leigh's counsel to remain in the army, convinced Scott to resume his military career once his suspension had been served. He rejoined the army in Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-sma ...

, where one of his first duties was to serve as judge advocate (prosecutor) in the court-martial of Colonel Thomas Humphrey Cushing.

War of 1812

declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, i ...

against Britain. After the declaration of war, Scott was promoted to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

and assigned as second-in-command of the 2d Artillery, serving under George Izard

George Izard (October 21, 1776 – November 22, 1828) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served as the second governor of Arkansas Territory from 1825 to 1828. He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 18 ...

. While Izard continued to recruit soldiers, Scott led two companies north to join General Stephen Van Rensselaer's militia force, which was preparing for an invasion of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

made the invasion the central part of his administration's war strategy in 1812, as he sought to capture Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

and thereby take control of the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

and cut off Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

from Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

. The invasion would begin with an attack on the town of Queenston

Queenston is a compact rural community and unincorporated place north of Niagara Falls in the Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada. It is bordered by Highway 405 to the south and the Niagara River to the east; its location at the eponym ...

, which was just across the Niagara River from Lewiston, New York

Lewiston is a town in Niagara County, New York, United States. The population was 15,944 at the 2020 census. The town and its contained village are named after Morgan Lewis, a governor of New York.

The Town of Lewiston is on the western bord ...

.

In October 1812, Van Rensselaer's force attacked British forces in the Battle of Queenston Heights. Scott led an artillery bombardment that supported an American crossing of the Niagara River, and he took command of American forces at Queenston after Colonel

In October 1812, Van Rensselaer's force attacked British forces in the Battle of Queenston Heights. Scott led an artillery bombardment that supported an American crossing of the Niagara River, and he took command of American forces at Queenston after Colonel Solomon Van Rensselaer

Solomon van Vechten van Rensselaer (August 9, 1774 – April 23, 1852) was a United States representative from the state of New York, a lieutenant colonel during the War of 1812, and postmaster of Albany for 17 years.

Early life

Solomon van ...

was badly wounded. Shortly after Scott took command, a British column under Roger Hale Sheaffe arrived. Sheaffe's numerically superior force compelled an American retreat, ultimately forcing Scott to surrender after reinforcements from the militia failed to materialize. As a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

, Scott was treated hospitably by the British, although two Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

* Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

* Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been ...

leaders nearly killed him while he was in British custody. As part of a prisoner exchange, Scott was released in late November; upon his return to the United States, he was promoted to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

and appointed to command the 2d Artillery. He also became the chief of staff to Henry Dearborn

Henry Dearborn (February 23, 1751 – June 6, 1829) was an American military officer and politician. In the Revolutionary War, he served under Benedict Arnold in his expedition to Quebec, of which his journal provides an important record ...

, who was the senior general of the army and personally led operations against Canada in the area around Lake Ontario.

Dearborn assigned Scott to lead an attack against Fort George, which commanded a strategic position on the Niagara River. With help from naval commanders Isaac Chauncey

Isaac Chauncey (February 20, 1772 – January 27, 1840) was an American naval officer in the United States Navy who served in the Quasi-War, The Barbary Wars and the War of 1812. In the latter part of his naval career he was President of th ...

and Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry (August 23, 1785 – August 23, 1819) was an American naval commander, born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The best-known and most prominent member

of the Perry family naval dynasty, he was the son of Sarah Wallace A ...

, Scott landed American forces behind the fort, forcing its surrender. Scott was widely praised for his conduct in the battle, although he was personally disappointed that the bulk of the British garrison escaped capture. As part of another campaign to capture Montreal, Scott forced the British to withdrawal from Hoople Creek in November 1813. Despite this success, the campaign fell apart after the American defeat at the Battle of Crysler's Farm

The Battle of Crysler's Farm, also known as the Battle of Crysler's Field, was fought on 11 November 1813, during the War of 1812 (the name ''Chrysler's Farm'' is sometimes used for the engagement, but ''Crysler'' is the proper spelling). A Brit ...

, and after Wilkinson (who had taken command of the front in August) and Hampton failed to cooperate on a strategy to take Montreal. With the failure of the campaign, President Madison and Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr.

John Armstrong Jr. (November 25, 1758April 1, 1843) was an American soldier, diplomat and statesman who was a delegate to the Continental Congress, U.S. Senator from New York, and United States Secretary of War under President James Madison. A me ...

relieved Wilkinson and some other senior officers of their battlefield commands. They were replaced with younger officers such as Scott, Izard, and Jacob Brown

Jacob Jennings Brown (May 9, 1775 – February 24, 1828) was known for his victories as an American army officer in the War of 1812, where he reached the rank of general. His successes on the northern border during that war made him a national ...

. In early 1814, Scott was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

and was assigned to lead a regiment under Brown.

In mid-1814, Scott took part in another invasion of Canada, which began with a crossing of the Niagara River under Brown's command. Scott was instrumental in the American success at the Battle of Chippawa, which took place on July 5, 1814. Though the battle was regarded as inconclusive from the strategic point of view because the British army remained intact, it was seen as an important moral victory. It was "the first real success attained by American troops against British regulars."

Later in July 1814, a scouting expedition led by Scott was ambushed, beginning the Battle of Lundy's Lane. Scott's brigade was decimated after General Gordon Drummond

General Sir Gordon Drummond, GCB (27 September 1772 – 10 October 1854) was a Canadian-born British Army officer and the first official to command the military and the civil government of Canada. As Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, Dr ...

arrived with British reinforcements, and he was placed in the reserve in the second phase of the battle. He was later badly wounded while seeking a place to commit his reserve forces. Scott believed that Brown's decision to refrain from fully committing his strength at the outset of this battle resulted in the destruction of Scott's brigade and a high number of unnecessary deaths. The battle ended inconclusively after General Brown ordered his army to withdraw, effectively bringing an end to the invasion. Scott spent the next months convalescing under the supervision of military doctors and physician Philip Syng Physick.

Scott's performance at the Battle of Chippawa had earned him national recognition. He was promoted to the brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

and awarded a Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress. It is Congress's highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions by individuals or institutions. The congressional pract ...

. In October 1814, Scott was appointed commander of American forces in Maryland and northern Virginia, taking command in the aftermath of the Burning of Washington

The Burning of Washington was a British invasion of Washington City (now Washington, D.C.), the capital of the United States, during the Chesapeake Campaign of the War of 1812. It is the only time since the American Revolutionary War that a ...

. The War of 1812 came to an effective end in February 1815, after news of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

(which had been signed in December 1814) reached the United States.

In 1815, Scott was admitted to the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati as an honorary member, in recognition of his service in the War of 1812. Scott's Society of the Cincinnati insignia, made by silversmiths Thomas Fletcher and Sidney Gardiner of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, was a one-of-a-kind, solid gold eagle measuring nearly three inches in height. It is one of the most unique military society insignias ever produced. There are no known portraits or photographs of Scott wearing the insignia, which is now in the collection of the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

Museum.

Family

In March 1817, Scott married Maria DeHart Mayo (1789–1862). She was the daughter of Abigail (

In March 1817, Scott married Maria DeHart Mayo (1789–1862). She was the daughter of Abigail (née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

DeHart) Mayo and Colonel John Mayo, a wealthy engineer and businessman who came from a distinguished family in Virginia. Scott and his family lived in Elizabethtown, New Jersey Elizabeth Township, also called Elizabethtown, was a township that existed in Essex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, from 1664 until 1855.

The area was initially part of the Elizabethtown Tract, purchased from the Lenape on October 28, 16 ...

for most of the next thirty years. Beginning in the late 1830s, Maria spent much of her time in Europe because of a bronchial condition, and she died in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in 1862. They were the parents of seven children, five daughters and two sons:

* Maria Mayo Scott (1818–1833), who died as a teenager.

* John Mayo Scott (1819–1820), who died young.

* Virginia Scott (1821–1845), who became Sister Mary Emanuel of the Georgetown convent of Visitation nuns.

* Edward Winfield Scott (1823–1827), who died young.

* Cornelia Winfield Scott (1825–1885), who married Colonel Henry Lee Scott (1814–1886) (no relation), Winfield Scott's aide-de-camp and Inspector General of the Army.

* Adeline Camilla Scott (1831–1882), who married Goold Hoyt (1818–1883), a New York City businessman.

* Marcella Scott (1834–1909), who married Charles Carroll MacTavish (1818–1868), the grandson of Richard Caton

Richard Caton (1842, Bradford – 1926), of Liverpool, England, was a British physician, physiologist and Lord Mayor of Liverpool who was crucial in discovering the electrical nature of the brain and laid the groundwork for Hans Berger to disco ...

and a member of Maryland's prominent Carroll family

O'Carroll ( ga, Ó Cearbhaill), also known as simply Carroll, Carrol or Carrell, is a Gaelic Irish clan which is the most prominent sept of the Ciannachta (also known as Clan Cian). Their genealogies claim that they are kindred with the Eógana ...

.

Mid-career, 1815–1841

Post-war years

With the conclusion of the War of 1812, Scott served on a board charged with demobilizing the army and determining who would continue to serve in the officer corps.Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

and Brown were selected as the army's two major generals, while Alexander Macomb, Edmund P. Gaines

Edmund Pendleton Gaines (March 20, 1777 – June 6, 1849) was a career United States Army officer who served for nearly fifty years, and attained the rank of major general by brevet. He was one of the Army's senior commanders during its format ...

, Scott, and Eleazer Wheelock Ripley

Eleazer Wheelock Ripley (April 15, 1782 – March 2, 1839) was an American soldier and politician. He fought in the War of 1812, eventually rising to the rank of brigadier general, and later served as a U.S. Representative from Louisiana, f ...

would serve as the army's four brigadier generals. Jackson became commander of the army's Southern Division, Brown became commander of the army's Northern Division, and the brigadier generals were assigned leadership of departments within the divisions. Scott obtained a leave of absence to study warfare in Europe, though to his disappointment, he reached Europe only after Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

. Upon his return to the United States in May 1816, he was assigned to command army forces in parts of the Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

. He made his headquarters in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

and became an active part of the city's social life. He earned the nickname "Old Fuss and Feathers" for his insistence on proper military bearing, courtesy, appearance and discipline. In 1835, Scott wrote ''Infantry Tactics, Or, Rules for the Exercise and Maneuvre of the United States Infantry'', a three-volume work that served as the standard drill manual for the United States Army until 1855.

Scott developed a rivalry with Jackson after the latter took offense to a comment Scott had made at a private dinner in New York, though they later reconciled. He also continued a bitter feud with Gaines that centered over which of them had seniority, as both hoped to eventually succeed the ailing Brown. In 1821, Congress reorganized the army, leaving Brown as the sole major general and Scott and Gaines as the lone brigadier generals; Macomb accepted demotion to colonel and appointment as the chief of engineers, while Ripley and Jackson both left the army. After Brown died in 1828, President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

passed over both Scott and Gaines due to their feuding, instead appointing Macomb as the senior general in the army. Scott was outraged at the appointment and asked to be relieved of his commission, but he ultimately backed down.

Black Hawk War and Nullification Crisis

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson ordered Scott to

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson ordered Scott to Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

to take command of a conflict known as the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", crosse ...

. By the time Scott arrived in Illinois, the conflict had come to a close with the army's victory at the Battle of Bad Axe

The Bad Axe Massacre was a massacre of Sauk (Sac) and Fox Indians by United States Army regulars and militia that occurred on August 1–2, 1832. This final scene of the Black Hawk War took place near present-day Victory, Wisconsin in the Uni ...

. Scott and Governor John Reynolds concluded the Black Hawk Purchase

The Black Hawk Purchase, also known as the Forty-Mile Strip or Scott's Purchase, extended along the West side of the Mississippi River from the north boundary of Missouri North to the Upper Iowa River in the northeast corner of Iowa. It was fif ...

with Chief Keokuk and other Native American leaders, opening up much of present-day Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

to settlement by whites. Later in 1832, Jackson placed Scott in charge of army preparations for a potential conflict arising from the Nullification Crisis. Scott traveled to Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, the center of the nullification movement, where he strengthened federal forts but also sought to cultivate public opinion away from secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

. Ultimately, the crisis came to an end in early 1833 with the passage of the Tariff of 1833

The Tariff of 1833 (also known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, ch. 55, ), enacted on March 2, 1833, was proposed by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was ...

.

Indian Removal

President Jackson initiated a policy ofIndian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

, forcibly relocating Native Americans to the west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. Some Native Americans moved peacefully, but others, including many Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

s, forcibly resisted. In December 1835, the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans and ...

broke out after the Dade massacre

The Dade battle (often called the Dade massacre) was an 1835 military defeat for the United States Army. The U.S. was attempting to force the Seminoles to move away from their land in Florida and relocate to Indian Territory (in what would becom ...

, in which a group of Seminoles ambushed and massacred a U.S. Army company in Central Florida

Central Florida is a region of the U.S. state of Florida. Different sources give different definitions for the region, but as its name implies it is usually said to comprise the central part of the state, including the Tampa Bay area and the Gr ...

. President Jackson ordered Scott to personally take command of operations against the Seminole, and Scott arrived in Florida by February 1836. After several months of inconclusive campaigning, he was ordered to the border of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

to put down a Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsCreek War of 1836

The Creek War of 1836, also known as the Second Creek War or Creek Alabama Uprising, was a conflict in Alabama at the time of Indian Removal between the Muscogee Creek people and non-native land speculators and squatters.

Although the Creek ...

. American forces under Scott, General Thomas Jesup

Thomas Sidney Jesup (December 16, 1788 – June 10, 1860) was a United States Army officer known as the "Father of the Modern Quartermaster Corps". His 52-year (1808–1860) military career was one of the longest in the history of the United St ...

, and Alabama Governor Clement Comer Clay

Clement Comer Clay (December 17, 1789 – September 6, 1866) was the eighth Governor of the U.S. state of Alabama from 1835 to 1837. An attorney, judge and politician, he also was elected to the state legislature, as well as to the House of Repr ...

quickly defeated the Muscogee. Scott's actions in the campaigns against the Seminole and the Muscogee received criticism from some subordinates and civilians, and President Jackson initiated a Court of Inquiry that investigated both Scott and Gaines. The court cleared Scott of misconduct but reprimanded him for the language he used in criticizing Gaines in official communications. The court was critical of Gaines' actions during the campaign, though it did not accuse him of misconduct or incompetence. It also criticized the language he used to defend himself, both publicly and to the court.

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, a personal friend of Scott's, assumed the presidency in 1837, and Van Buren continued Jackson's policy of Indian removal. In April 1838, Van Buren placed Scott in command of the removal of Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

from the Southeastern United States. Some of Scott's associates tried to dissuade Scott from taking command of what they viewed as an immoral mission, but Scott accepted his orders. After almost all of the Cherokee refused to voluntarily relocate, Scott drew up careful plans in an attempt to ensure that his soldiers forcibly, but humanely, relocated the Cherokee. Nonetheless, the Cherokee endured abuse from Scott's soldiers; one account described soldiers driving the Cherokee "like cattle, through rivers, allowing them no time to take off their shoes and stockings. In mid-1838, Scott agreed to Chief John Ross's plan to let the Cherokee lead their own movement west, and he awarded a contract to the Cherokee Council to complete the removal. Scott was strongly criticized by many Southerners, including Jackson, for awarding the contract to Ross rather than continuing the removal under his own auspices Scott accompanied one Cherokee group as an observer, traveling with them from Athens, Tennessee

Athens is the county seat of McMinn County, Tennessee, United States and the principal city of the Athens Micropolitan Statistical Area has a population of 53,569. The city is located almost equidistantly between the major cities of Knoxville an ...

to Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the List of muni ...

, where he was ordered to the Canada–United States border

The border between Canada and the United States is the longest international border in the world. The terrestrial boundary (including boundaries in the Great Lakes, Atlantic, and Pacific coasts) is long. The land border has two sections: Can ...

.

Tensions with the United Kingdom

In late 1837, the so-called "Patriot War

The Patriot War was a conflict along the Canada–United States border in which bands of raiders attacked the British colony of Upper Canada more than a dozen times between December 1837 and December 1838. This so-called war was not a conflic ...

" broke out along the Canadian border as some Americans sought to support the Rebellions of 1837–1838

The Rebellions of 1837–1838 (french: Les rébellions de 1837), were two armed uprisings that took place in Lower and Upper Canada in 1837 and 1838. Both rebellions were motivated by frustrations with lack of political reform. A key shared g ...

in Canada. Tensions further escalated due to an incident known as the Caroline affair

The ''Caroline'' affair (also known as the ''Caroline'' case) was a diplomatic crisis beginning in 1837 involving the United States, the UK, and the Canadian independence movement. The modest military incident has taken grand international l ...

, in which Canadian forces burned a steamboat that had been used to deliver supplies to rebel forces. President Van Buren dispatched Scott to Western New York

Western New York (WNY) is the westernmost region of the U.S. state of New York. The eastern boundary of the region is not consistently defined by state agencies or those who call themselves "Western New Yorkers". Almost all sources agree WNY i ...

to prevent unauthorized border crossings and prevent the outbreak of a war between the United States and the United Kingdom. Still popular in the area due to his service in the War of 1812, Scott issued public appeals, asking Americans to refrain from supporting the Canadian rebels. In late 1838, a new crisis known as the Aroostook War

The Aroostook War (sometimes called the Pork and Beans WarLe Duc, Thomas (1947). The Maine Frontier and the Northeastern Boundary Controversy. ''The American Historical Review'' Vol. 53, No. 1 (Oct., 1947), pp. 30–41), or the Madawaska War, wa ...

broke out over a dispute regarding the border between Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

and Canada, which had not been conclusively settled in previous treaties between Britain and the United States. Scott was tasked with preventing the conflict from escalating into a war. After winning the support of Governor John Fairfield

John Fairfield (January 30, 1797December 24, 1847) was an attorney and politician from Maine. He served as a U.S. Congressman, governor and U.S. Senator.

was born in Pepperellborough, Massachusetts (now Saco, Maine) and attended the school ...

and other Maine leaders, Scott negotiated a truce with John Harvey John Harvey may refer to:

People Academics

* John Harvey (astrologer) (1564–1592), English astrologer and physician

* John Harvey (architectural historian) (1911–1997), British architectural historian, who wrote on English Gothic architecture ...

, who commanded British forces in the area.

Presidential election of 1840

In the mid-1830s, Scott joined the Whig Party, which was established by opponents of President Jackson. Scott's success in preventing war with Canada under Van Buren confirmed his popularity with the broad public, and in early 1839 newspapers began to mention him as a candidate for the presidential nomination at the 1839 Whig National Convention. By the time of the convention in December 1839, party leader Henry Clay and 1836 presidential candidate

In the mid-1830s, Scott joined the Whig Party, which was established by opponents of President Jackson. Scott's success in preventing war with Canada under Van Buren confirmed his popularity with the broad public, and in early 1839 newspapers began to mention him as a candidate for the presidential nomination at the 1839 Whig National Convention. By the time of the convention in December 1839, party leader Henry Clay and 1836 presidential candidate William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

had emerged as the two front-runners, but Scott loomed as a potential compromise candidate if the convention deadlocked. After several ballots, the convention nominated Harrison for president. Harrison went on to defeat Van Buren in the 1840 presidential election, but he died just one month into his term and was succeeded by Vice President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president in 1841. He was elected vice president on the 1840 Whig tick ...

.

Commanding General, 1841–1861

Service under Tyler

On June 25, 1841, Macomb died, and Scott and Gaines were still the two most obvious choices for the position of

On June 25, 1841, Macomb died, and Scott and Gaines were still the two most obvious choices for the position of Commanding General of the United States Army

The Commanding General of the United States Army was the title given to the service chief and highest-ranking officer of the United States Army (and its predecessor the Continental Army), prior to the establishment of the Chief of Staff of the ...

. Secretary of War John Bell recommended Scott, and President Tyler approved; Scott was also promoted to the rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

. According to biographer John Eisenhower

John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower (August 3, 1922 – December 21, 2013) was a United States Army officer, diplomat, and military historian. He was a son of President Dwight D. Eisenhower and First Lady Mamie Eisenhower. His military career sp ...

, the office of commanding general had, since its establishment in 1821, been an "innocuous and artificial office ... its occupant had been given little control over the staff, and even worse, his advice was seldom sought by his civilian superiors." Macomb had largely been outside of the chain-of-command, and senior commanders like Gaines, Scott, and Quartermaster General Thomas Jesup reported directly to the Secretary of War. Despite Scott's efforts to invigorate the office, he enjoyed little influence with President Tyler, who quickly became alienated from most of the rest of the Whig Party after taking office. Some Whigs, including Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

of Pennsylvania, favored Scott as the Whig candidate in the 1844 presidential election, but Clay quickly emerged as the prohibitive front-runner for the Whig nomination. Clay won the 1844 Whig nomination, but he was defeated in the general election by Democrat James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

. Polk's campaign centered on his support for the annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas ( es, República de Tejas) was a sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846, that bordered Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840 (another breakaway republic from Mex ...

, which had gained independence from Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

in 1836. After Polk won the election, Congress passed legislation enabling the annexation of Texas, and Texas gained statehood in 1845.

Mexican–American War

Early war

Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

, a Mexican province. The United States nearly went to war with Britain over Oregon, but the two powers ultimately agreed to partition

Partition may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Disk partitioning, the division of a hard disk drive

* Memory partition, a subdivision of a computer's memory, usually for use by a single job

Software

* Partition (database), the division of a ...

Oregon Country at the 49th parallel north. The Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

broke out in April 1846 after U.S. forces under the command of Brigadier General Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

clashed with Mexican forces north of the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

in a region claimed by both Mexico and Texas. Polk, Secretary of War William L. Marcy, and Scott agreed on a strategy in which the U.S. would capture Northern Mexico

Northern Mexico ( es, el Norte de México ), commonly referred as , is an informal term for the northern cultural and geographical area in Mexico. Depending on the source, it contains some or all of the states of Baja California, Baja California ...

and then pursue a favorable peace settlement. While Taylor led the army in Northern Mexico, Scott presided over the expansion of the army, ensuring that new soldiers were properly supplied and organized.

Invasion of Central Mexico

Taylor won several victories against the Mexican army, but Polk eventually came to the conclusion that merely occupying Northern Mexico would not compel Mexico to surrender. Scott drew up an invasion plan that would begin with a naval assault on the

Taylor won several victories against the Mexican army, but Polk eventually came to the conclusion that merely occupying Northern Mexico would not compel Mexico to surrender. Scott drew up an invasion plan that would begin with a naval assault on the Gulf

A gulf is a large inlet from the ocean into the landmass, typically with a narrower opening than a bay, but that is not observable in all geographic areas so named. The term gulf was traditionally used for large highly-indented navigable bodies ...

port of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

and end with the capture of Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

. With Congress unwilling to establish the rank of lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

for Democratic Senator Thomas Hart Benton, Polk reluctantly turned to Scott to command the invasion. Among those who joined the campaign were several officers who would later distinguish themselves in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, including Major Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia secede ...

, Captain Robert E. Lee, and Lieutenants Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, George G. Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

, and P. G. T. Beauregard. While Scott prepared the invasion, Taylor inflicted what the U.S. characterized as a crushing defeat on the army of Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

at the Battle of Buena Vista

The Battle of Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847), known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between the US invading forces, l ...

. In the encounter known in Mexico as the Battle of La Angostura, Santa Anna brought U.S. forces to near collapse, capturing cannons and flags, and returned to Mexico City, leaving U.S. forces on the field. Santa Anna left to put down a minor insurrection, and recruited a new army.

According to biographer John Eisenhower, the invasion of Mexico through Veracruz was "up to that time the most ambitious amphibious expedition in human history." The operation commenced on March 9, 1847 with the Siege of Veracruz

The Battle of Veracruz was a 20-day siege of the key Mexican beachhead seaport of Veracruz during the Mexican–American War. Lasting from March 9–29, 1847, it began with the first large-scale amphibious assault conducted by United States ...