Wedding Of Princess Elizabeth And Frederick V Of The Palatinate on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The wedding of Princess Elizabeth (1596–1662), daughter of

The wedding of Princess Elizabeth (1596–1662), daughter of

The treasurer of the navy

The treasurer of the navy

The marriage took place on Sunday 14 February 1613 in the chapel of

The marriage took place on Sunday 14 February 1613 in the chapel of

De Guiana, Carmen Epicum

'. In the poem Chapman outlines a female and Elizabethan England that would be a sibling and a mother to Guiana in "a golden world". A marshal attending the performers and audience, "Baughan", was probably the usher of Anne of Denmark, who had previously fought with Edward Herbert over a hair ribbon worn by a maid of honour, Mary Middlemore. A drawing by

There was some controversy over the continued entertainment of Frederick and the expense. On 24 February Anne of Denmark, with Frederick and Elizabeth, attended the christening of the daughter of the Countess of Salisbury. The next day the luxurious coach that Frederick had ordered in Paris arrived. The coach became the responsibility of her Scottish Master of Horse Andrew Keith. Keith later got into a fight at Heidelberg.

On 10 April

There was some controversy over the continued entertainment of Frederick and the expense. On 24 February Anne of Denmark, with Frederick and Elizabeth, attended the christening of the daughter of the Countess of Salisbury. The next day the luxurious coach that Frederick had ordered in Paris arrived. The coach became the responsibility of her Scottish Master of Horse Andrew Keith. Keith later got into a fight at Heidelberg.

On 10 April

Maria Shmygol, 'A Representation of Algiers in Early Modern London', Medieval and Early Modern Orients

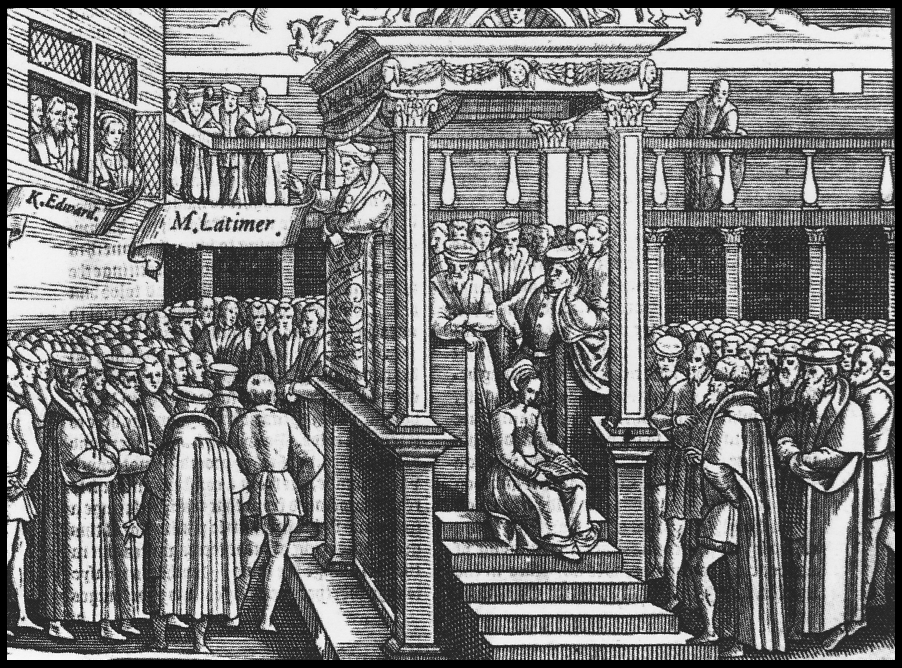

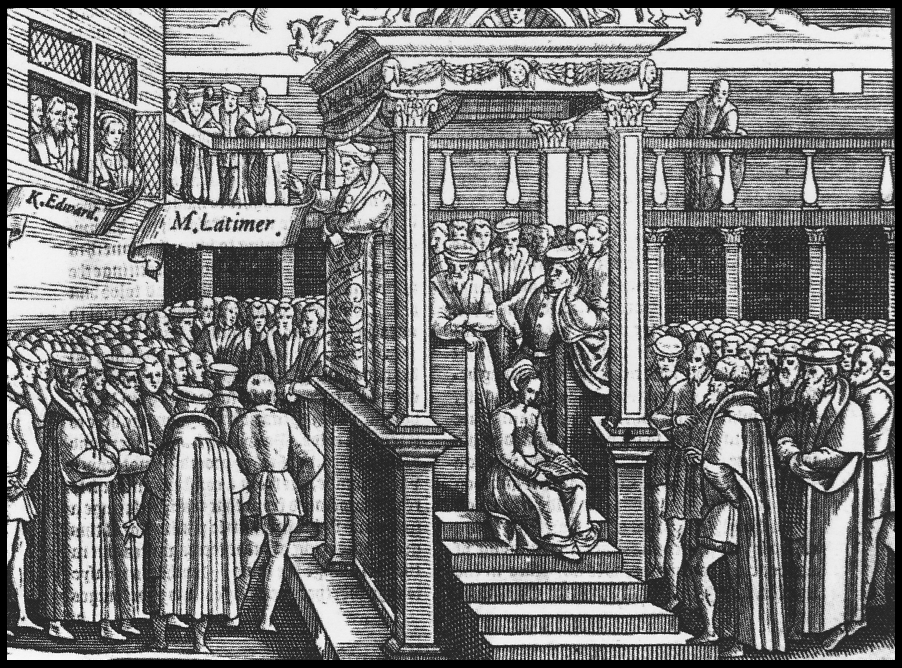

Engraving of the Wedding Procession, attributed to Abraham Hogenberg, Met

Silver gilt commemorative medal with portraits of Elizabeth & Frederick, British Museum

Embarkation at Margate of the Elector Palatine and Princess Elizabeth, Adam Willaerts, RCT

Richard Cavendish, The Marriage of the Winter Queen, History Today

A royal wedding for Valentine's Day, 1613, History of Parliament

Ruth Selman, Royal weddings in history: a Stuart Valentine, The National Archives

Campion's ''The Lord's Masque'', 1613, British Library

'The Winter Queen' Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, V&A

The 1613 Marriage Journey of Elizabeth Stuart, Stanford University Spatial History Project

Court of James VI and I 1613 in England

The wedding of Princess Elizabeth (1596–1662), daughter of

The wedding of Princess Elizabeth (1596–1662), daughter of James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

, and Frederick V of the Palatinate

Frederick V (german: link=no, Friedrich; 26 August 1596 – 29 November 1632) was the Elector Palatine of the Rhine in the Holy Roman Empire from 1610 to 1623, and reigned as King of Bohemia from 1619 to 1620. He was forced to abdicate both r ...

(1596–1632) was celebrated in London in February 1613. There were fireworks, masques (small, choreography-based plays), tournaments, and a mock-sea battle or naumachia

The naumachia (in Latin , from the Ancient Greek /, literally "naval combat") in the Ancient Roman world referred to both the staging of naval battles as mass entertainment, and the basin or building in which this took place.

Early

The fir ...

. Preparations involved the construction of a "Marriage room", a hall adjacent to the 1607 Banqueting House

In English architecture, mainly from the Tudor period onwards, a banqueting house is a separate pavilion-like building reached through the gardens from the main residence, whose use is purely for entertaining, especially eating. Or it may be b ...

at Whitehall Palace

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

. The events were described in various contemporary pamphlets and letters.

Arrival of the Count Palatine

Frederick arrived atGravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Ro ...

on 16 October 1612. He was met by Lewes Lewknor

Sir Lewes Lewknor (c.1560–1627) was an English courtier, M.P., writer, soldier, and Judge who served as Master of the Ceremonies to King James I of England. M.P. for Midhurst in 1597 and for Bridgnorth 1604–10. His career has been descri ...

, the master of ceremonies, and he decided to come to London by river. The Duke of Lennox

The title Duke of Lennox has been created several times in the peerage of Scotland, for Clan Stewart of Darnley. The dukedom, named for the district of Lennox in Dumbarton, was first created in 1581, and had formerly been the Earldom of Lenno ...

brought him to the water gate of Whitehall Palace

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

where he met Prince Charles, known as the Duke of York. He went into the newly built Banqueting Hall (or rather a new adjacent hall, the banqueting house had been built in 1607) to meet King James. They spoke in French, as it seems Elizabeth did not speak much German, and Frederick did not speak much English. Frederick kissed the hem of Elizabeth's dress. The King took him to his bedchamber and gave him a ring. He was lodged at Essex House. His companions included two counts of the House of Nassau

The House of Nassau is a diversified aristocratic dynasty in Europe. It is named after the lordship associated with Nassau Castle, located in present-day Nassau, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. The lords of Nassau were originally titled "Count ...

, with Count John of Nassau or John Albrecht of Solms, and Henry, Prince of Nassau.

According to popular opinion, Elizabeth's mother Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

had not been keen on the marriage, and believed that Elizabeth was marrying below her station, but after meeting him, "was much pleased with him". He was said not to enjoy tennis or riding, but only his conversations with Princess Elizabeth. He changed his lodging to the late Lord Treasurer's house, apparently Salisbury House on the Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

.Thomas Birch

Thomas Birch (23 November 17059 January 1766) was an English historian.

Life

He was the son of Joseph Birch, a coffee-mill maker, and was born at Clerkenwell.

He preferred study to business but, as his parents were Quakers, he did not go to t ...

& Folkestone Williams, ''Court and Times of James the First'', vol. 1 (London, 1848), pp. 198 (has Great Chamber rather than Banqueting House, while Foscarini said the hall was that used for dances), p. 201: Henry Ellis, ''Original Letters'', 3rd series vol. 4 (London, 1846), pp. 170–3.

Elizabeth's wardrobe was updated with silks and satin from Baptist Hicks

Baptist Hicks, 1st Viscount Campden (1551 – 18 October 1629) was an English cloth merchant and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1621 and 1628. King James I knighted Hicks in 1603 and in 1620 he was created a baronet.

He w ...

and Thomas Woodward, gold lace from Christopher Weever, and John Spence made her whalebone "bodies" and farthingale

A farthingale is one of several structures used under Western European women's clothing in the 16th and 17th centuries to support the skirts in the desired shape and enlarge the lower half of the body. It originated in Spain in the fifteenth c ...

s. This was noted by the Venetian ambassador Antonio Foscarini

Antonio Foscarini (c. 1570 in Venice – April 22, 1622) belonged to the Venetian nobility and was Venetian ambassador to Paris and later to London. He was the third son of Nicolò di Alvise of the family branch of San Polo and Maria Barbarigo di ...

as an adornment to her great natural beauty. David Murray, a Scottish poet in the household of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales (19 February 1594 – 6 November 1612), was the eldest son and heir apparent of James VI and I, King of England and Scotland; and his wife Anne of Denmark. His name derives from his grandfathers: Henry Stuar ...

, organised the embroidery of the wedding gown. William Brothericke, an embroiderer, made hangings for the bride-chamber. A fool at court, Archibald Armstrong

Archibald Armstrong (died March 1672), court jester, called "Archy", was a native of Cumberland, and according to tradition first distinguished himself as a sheep thief; afterwards he entered the service of James VI, with whom he became a favourit ...

, was bought a crimson velvet coat with gold lace to wear at the wedding.

Prince Henry, heir to the throne, died due to fever on 6 November 1612. The wedding was postponed in a period of mourning and grief. His death also affected the entertainments at the wedding in February, as the themes of masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A masque ...

s were invested with the political aspirations of their patrons. Henry and Elizabeth's plans for masques were abandoned or modified.

Frederick joined King James in the country at Royston and Theobalds

Theobalds House (also known as Theobalds Palace) in the parish of Cheshunt in the English county of Hertfordshire, was a significant stately home and (later) royal palace of the 16th and early 17th centuries. Set in extensive parkland, it was a r ...

. Elizabeth obtained one of her late brother's night gowns. Frederick's cook brought her a pike dressed in the German fashion. King James came back from the country and played cards with Elizabeth at Whitehall, almost every night (lost stakes are recorded in her accounts). Some courtiers now thought Elizabeth should not marry and leave England. There were rumours that since the death of Prince Henry a Scottish faction at court advocated a marriage with the Marquess of Hamilton instead. This alternative could ensure the future of the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

as the Hamiltons also had a place in the royal succession.

January 1613

The marriage contract was finalized, and in a ceremony at Whitehall on St John's Day, 27 December, Frederick took Elizabeth's hand in her bedchamber and led her to the King in the Banqueting Hall, where they kneeled on a Turkish carpet and received his blessing and then the Archbishop of Canterbury's. The letter writer John Chamberlain heard that the contracts were read out byThomas Lake

Sir Thomas Lake PC (1567 – 17 September 1630) was Secretary of State to James I of England. He was a Member of Parliament between 1593 and 1626.

Thomas Lake was baptised in Southampton on 11 October 1567, the son of Almeric Lake, a minor cus ...

, but the poor quality of the translations made the guests laugh out loud. Frederick was in purple velvet trimmed with gold, Elizabeth wore mourning black satin with silver lace, with a cloak of black "semé velvet" (sprinkled with silver flowers or crosslets) trimmed with gold lace, and a plume of white feathers in her attire. White feathers were immediately adopted by fashionable London. Her mother, Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

, was absent, suffering from painful gout.Edmund Sawyer, ''Memorials of Affairs of State from the Papers of Ralph Winwood'', 3 (London, 1725), p. 421: Green & Lomas, ''Elizabeth, Electress Palatine and Queen of Bohemia'' (London, 1909), pp. 45–6, citing TNA SP 81/12/73: Nichols, ''Progresses'', 2 (London, 1828), pp. 513–5: Maria Hayward, ''Stuart Style'' (Yale, 2020), p. 88. After the ceremony Frederick and Prince Charles went back to wearing mourning clothes.

A Scottish courtier Viscount Fenton sent the news that the couple were now "assured" to his kinsman in Stirling, adding, "The marriage is appointed to be on Saint Valentine's day and by mere accident". King James gave orders that the court should prepare their costume for the day, and not wear mourning clothes for Henry.

Frederick gave New Year's Day gifts including medals with his portrait to the women of Elizabeth's household including Theodosia Harington

Theodosia Harington, Lady Dudley (died 1649) was an English aristocrat who was abandoned by her husband, but maintained connections at court through her extensive family networks.

Early life

She was the eighth daughter of Sir James Harington of ...

. There were jewels bought in Germany, for Elizabeth "2 most rich pendant diamonds, and 2 most rich orientall pearles", a pair of earrings, which she wore in the following days, and more jewels for Anne of Denmark's gentlewomen and maids of honour, King James told Frederick not to overreach himself with gifts for all his servants.Allen B. Hinds, ''HMC Downshire'', vol. 4 (London, 1940), pp. 2, 8: Green & Lomas, ''Elizabeth, Electress Palatine and Queen of Bohemia'' (London, 1909), p. 46-7 citing TNA SP 12/81/141.

Frederick ordered more gifts from Paris, including caskets of jewels, and a particularly fabulous coach for Elizabeth covered inside and out with embroidered velvet. French courtiers, and even the Queen of France

This is a list of the women who were queens or empresses as wives of French monarchs from the 843 Treaty of Verdun, which gave rise to West Francia, until 1870, when the Third Republic was declared.

Living wives of reigning monarchs technica ...

visited the workshop to see it, as if it were "a precious monument". On 7 February Frederick was made a knight of the Order of Garter in St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

. Elizabeth went to stay at St James' Palace. They were both sixteen years old when they married.

Ambassadors attempted to gain advantage over rival diplomats by securing invitations to the feasts and masques. It was noted that the wife of the ambassador of the Archduke of Savoy visited Somerset House and danced before the queen. Anne of Denmark was said to have warmed to Frederick, caressed him, and had ordered new livery clothes for her household. As the wedding drew near the City raised a volunteer guard of 500 musketeers.

James Nisbet and Edinburgh's gift to Princess Elizabeth

The city of Edinburgh sent a gift of 10,000merks

The merk is a long-obsolete Scottish silver coin. Originally the same word as a money mark of silver, the merk was in circulation at the end of the 16th century and in the 17th century. It was originally valued at 13 shillings 4 pence (exactly ...

, as promised at Elizabeth's baptism in November 1596. James Nisbet was sent to London with the cash. He presented her with a diamond necklace on the day of the wedding and the money three days later. A detailed account of his expenses survives. He had a new suit of clothes made in Edinburgh, and hired a horse from John Kinloch on 5 February. When he arrived in London he had a new taffeta cloak made up. He went to court to meet John Murray of the king's bedchamber. The King sent word that Nisbet should buy a jewel, "a carquan of diamonds of great value", to give to Elizabeth on the morning of the wedding as she waited in the gallery at Whitehall before going in procession to the Chapel Royal.

Nisbet found his linen "overlayers" to be unfashionable in London, and following strong hints about clothes and pleasing the king, he ordered new clothes to wear at the wedding in the same style as John Murray's. Robert Jousie

Robert Jousie (or Joussie or Jowsie or Jossie; died 1626) was a Scottish merchant, financier, and courtier.

Life

Jousie was a cloth merchant based in Edinburgh with a house on the High Street or Royal Mile. He became an exclusive supplier of fa ...

, a Scottish merchant and courtier who had relocated to London helped him. Patrick Black, formerly a tailor to Prince Henry, made him a suit of "villouris raze" with satin and Milan passments and a velvet cloak. A ''ras'' fabric was a velvet with a short nap. The outfit included a castor hat and a satin piccadill

A piccadill or pickadill is a large broad collar of cut-work lace that became fashionable in the late 16th century and early 17th century. The term is also used for the stiffened supporter or supportasse used to hold such a collar in place.

Th ...

.Marguerite Wood, ''Extracts from the Burgh Records of Edinburgh, 1604–1626'' (Edinburgh, 1931), p. 362.

Nisbet watched the fireworks from the Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

. He had his hair cut on Friday 12 February. On Saturday he bought the necklace for Elizabeth costing £815 sterling and watched the sea-fight. On Sunday he paid half a crown to book a place to watch the wedding processions, (after giving Elizabeth her jewel). On Saturday he saw the "masquerade". He lodged in King Street, socialised with Scots in London and saw four comedies. On 29 February Nisbet went to Newmarket to say his goodbye to King James. Elizabeth sent a thank-you letter to the Provost of Edinburgh

The Right Honourable Lord Provost of Edinburgh is the convener of the City of Edinburgh local authority, who is elected by the city council and serves not only as the chair of that body, but as a figurehead for the entire city, ex officio the ...

, James Nisbet's father-in-law Sir John Arnot

John Arnot of Birswick (Orkney) (1530–1616) was a 16th-century Scottish merchant and landowner who served as Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1587 to 1591 and from 1608 to death. He was Deputy Treasurer to King James VI.

Career

He was born ...

on 24 February.Marguerite Wood, ''Extracts from the Burgh Records of Edinburgh, 1604–1626'' (Edinburgh, 1931), pp. 357, 363–69.

The Lord Mayor and aldermen of London gave a chain of oriental pearls worth £2000, presented to Elizabeth by the Recorder of London

The Recorder of London is an ancient legal office in the City of London. The Recorder of London is the senior circuit judge at the Central Criminal Court (the Old Bailey), hearing trials of criminal offences. The Recorder is appointed by the Cr ...

, Henry Montagu

Henry Montagu, 1st Earl of Manchester (7 November 1642) was an English judge, politician and peer.

Life

He was the 3rd son of Edward Montagu of Boughton and grandson of Sir Edward Montagu, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench from 1539 to ...

, possibly at the same time as Edinburgh's gift.

Fireworks and sea-battles

The fireworks on Thursday 11 February were the work of John Nodes, Thomas Butler, William Betts, and William Fishenden, royal gunners. The theme was loosely based on the allegory in the first book ofEdmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

's ''The Faerie Queen

''The Faerie Queene'' is an English epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books IIII were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IVVI. ''The Faerie Queene'' is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and over 4,000 sta ...

'', a work of 1590 celebrating the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

. The costs were administered by Roger Dalison

Sir Roger Dalison, 1st Baronet (or Sir Roger Dallison or Dallyson) (c.1562 – 1620), of Laughton, Lincolnshire was an English courtier, Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance and Member of Parliament.

Career

He was the eldest son of William Dalison ...

, Lieutenant of the Royal Ordnance. The displays were mostly built on barges on the Thames, with a "fort and haven of Algiers" on land for the sea-battle, all intended to be visible from Whitehall Palace. There was a long gallery at Whitehall known as the river gallery, leading to Princess Mary's Lodging, with several large windows on to the river. There had been a comparable spectacle on the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

in May 1610, ''London's Love to Prince Henry

''London's Love to Prince Henry'' (31 May 1610), was a pageant on the River Thames organised by the city of London for the investiture of Prince Henry as Prince of Wales.

This pageant was performed on the Thames between Chelsea and Whitehall. I ...

''.

The poet John Taylor, known as the Water Poet, published an account of the "Fire and Water Triumphs" on Saturday, as ''Heaven's Blessing and Earth's Joy''. His publication includes lists of fireworks attributed to the each of the royal gunners.Nichols, ''Progresses'', 2 (London, 1828), pp. 527–35. The fireworks illustrated a theme or device, involving Lady Lucida, Queen of the Amazons, who spurned the love of the magician Mango, a "Tartarian". Mango had captured Lucida and her Amazons and imprisoned them in a pavilion, watched over by a dragon. Saint George, after feasting with Lucida, was ready to effect her rescue. The fireworks began, with fiery balls shooting into the air around the pavilion. A deer hunt with dogs appeared around the pavilion, and then "artificial men" spitting flame. As the whole pavilion went up in flames, Saint George rode over a bridge to the dragon's tower, the enchanted "Tower of Brumond". The next part of the action was devised by Thomas Butler. Saint George killed the dragon on the bridge, only to awaken a sleeping giant. The giant was vanquished and told Saint George that a drink from a sacred fountain was the only way to conquer Mango. The magician travelled to the castle using an invisible flying devil, and rockets started firing from the castle. Saint George captured Mango and his conjuring sceptre (wand) and tied him to a pillar.

Then followed a further firework display, credited to John Tindall, of an assault by three ships on the Castle of Envy on an island in the Sea of Disquiet. The castle was said to be built on a mount of adders, snakes, toads, serpents, and scorpions, all emitting fire. This description may have brought to mind a garden feature of Somerset House

Somerset House is a large Neoclassical complex situated on the south side of the Strand in central London, overlooking the River Thames, just east of Waterloo Bridge. The Georgian era quadrangle was built on the site of a Tudor palace ("O ...

designed for Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

by Salomon de Caus

Salomon de Caus (1576, Dieppe – 1626, Paris) was a French Huguenot engineer, once (falsely) credited with the development of the steam engine.

Biography

Caus was the elder brother of Isaac de Caus. Being a Huguenot, Caus spent his life moving a ...

, a Mount Parnassus carved with mussels and snails. This performance was not a complete success, John Chamberlain wrote, "the fireworks were reasonably well performed, all save the last castle of fire, which bred most expectation, and had most devices, but when it came to execution had worst success".

Sea-fight on the Thames

The treasurer of the navy

The treasurer of the navy Robert Mansell

Sir Robert Mansell (1573–1656) was an admiral of the English Royal Navy and a Member of Parliament (MP), mostly for Welsh constituencies. His name was sometimes given as Sir Robert Mansfield and Sir Robert Maunsell.

Early life

Mansel was a ...

was granted funds for "the naval fight to be had upon the river of Thames, for the more magnificent and royal solemnizing of the marriage of the Lady Elizabeth". Chamberlain calls Mansell the "Chief Commander" of the show, which was partly the work of the naval architect Phineas Pett

Phineas Pett (1 November 1570 – August 1647) was a shipwright and First Resident Commissioner of Chatham Dockyard and a member of the Pett dynasty. Phineas left a memoir of his activities which is preserved in the British Library and was publi ...

. The battle took place on the afternoon of Saturday 13 February between Lambeth Steps and Temple stairs, with a cordon or boom of tethered boats reserving a free passage for ordinary Thames traffic. King James, Anne of Denmark, and the royal party were seated on the privy stairs at Whitehall.

The show represented a battle between Christian and Turkish ships, including a Venetian argosy or caravel

The caravel (Portuguese: , ) is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing win ...

captained by Phineas Pett, near a Turkish harbour and castle of Argeir of Algiers built at Stangate at Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

. The castle was armed with 22 cannon. A Turkish watchtower at Lambeth was set on fire. After an English victory, captives in Turkish costume (red jackets with blue sleeves) were brought by the English admiral to Whitehall, where Robert Mansell presented them to the Earl of Nottingham who took them to King James.

John Taylor thought the action resembled the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

or the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

. John Chamberlain thought the event had fallen far short of expectation, and King James and the royals took no delight in the mere shooting of guns. Phineas Pett later wrote that he was in more danger on the Venetian argosy, which he had converted from an old pinnace

Pinnace may refer to:

* Pinnace (ship's boat), a small vessel used as a tender to larger vessels among other things

* Full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth c ...

, ''The Spy'', than if he had been on active sea-service. Several soldiers and sailors or workmen had been seriously injured, and plans for a second day were abandoned.

A royal debt of £693 for the "naval fight" was still unpaid three years later.

Wedding at Whitehall

The marriage took place on Sunday 14 February 1613 in the chapel of

The marriage took place on Sunday 14 February 1613 in the chapel of Whitehall Palace

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

, which was decorated with tapestry depicting the "Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its messag ...

". The tapestry had been bought by Henry VIII in 1542 and used to hang Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

at the coronation of Elizabeth I

The coronation of Elizabeth I as Queen of England and Ireland took place at Westminster Abbey, London, on 15 January 1559. Elizabeth I had ascended the throne at the age of 25 upon the death of her half-sister, Mary I, on 17 November 1558. Mary ...

.

A processional route was established around the palace so that the wedding party could be seen by more people. For the benefit of spectators around the palace and in adjacent buildings, a scaffold with a raised walkway crossed an open courtyard by the Preaching Place. King James went from the Privy Chamber through the Presence Chamber and Guard Chamber, and the new Banqueting House (or Marriage-Room), down stairs by the court gate, along the temporary walk-way, "a raised gallery conspicuous to all", to the Great Chamber and Lobby to the Closet, and down stairs to the Royal Chapel. Frederick went from the Banqueting Hall, and then Elizabeth, preceded by her tutor or guardian Lord Harington.

John Chamberlain was able to glimpse the procession from a pre-booked window of the Whitehall Jewel House or Revel's House. He saw the bride go from the stairs at the gallery by the Preaching Place onto the "terrace" or walkway, which he described as "a long stage or gallery which ran along the court into the hall". He thought King James was "somewhat strangely attired in a cap and feather, with a Spanish cape and a long stocking". He also noted that the daughters of the Earl of Northumberland

The title of Earl of Northumberland has been created several times in the Peerage of England and of Great Britain, succeeding the title Earl of Northumbria. Its most famous holders are the House of Percy (''alias'' Perci), who were the most po ...

and the Catholic Lord Montagu were very well dressed, a public show of loyalty when the groom was a leading Protestant prince.McClure, ''Letters of John Chamberlain'', vol. 1 (Philadelphia, 1939), pp. 423–5, 427, citing SP 14/72/46: Michael Questier, ''Catholicism and Community in Early Modern England'' (Cambridge, 2006), p. 383: Maria Hayward

Maria Hayward is an English historian of costume and early modern Britain.

She is a professor of history at the University of Southampton

, mottoeng = The Heights Yield to Endeavour

, type = Public researc ...

, ''Stuart Style'' (Yale, 2020), p. 82.

Elizabeth wore an imperial crown (but not with closed arches) set with diamonds and pearls, shining on her amber hair, let down to her waist, and dressed with rolls of gold spangles, pearls, precious stone and diamonds. Her white gown was richly embroidered by the workshop of Edward Hillyard. 14 or 15 (likely 16) ladies dressed in white satin like the bride held her train. Some accounts say the white costume was made of cloth of silver.

Her mother's page Piero Hugon brought a jewel for her to wear. The Venetian ambassador Foscarini noted that Elizabeth was wearing a diamond necklace, probably the one bought by James Nisbet. He wrote that there were 8 daughters of earls on either side of her train. Anne of Denmark, dressed in white satin, had a great number of pear-shaped pearls in her hair, and was ablaze with diamonds. Her jewels were thought to be worth £400,000. The hairstyles of the queen and her daughter were represented accordingly in a contemporary engraving of the wedding procession. Roger Wilbraham

Sir Roger Wilbraham (4 November 1553 – 31 July 1616) was a prominent English lawyer who served as Solicitor-General for Ireland under Elizabeth I and held a number of positions at court under James I, including Master of Requests and survey ...

wrote, "the Court abounding in jewels and embroidery beyond custom or reason: God grant money to pay debts". According to a surviving record, the wedding of Elizabeth and Frederick, cost £93,293 pounds in total, which equates to approximately £9,131,518 today.

The Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

officiated. Elizabeth was nervous during the ceremony and could not help laughing. Afterwards the guests drank spiced hippocras

Hippocras ( ca, Pimentes de clareya; lat, vīnum Hippocraticum), sometimes spelled hipocras or hypocras, is a drink made from wine mixed with sugar and spices, usually including cinnamon, and possibly heated. After steeping the spices in the ...

wine. Dinner for the bride and bridegroom with the ambassadors was served in the new purpose-built room, which was hung with tapestry depicting the defeat of the Spanish Armada.

The event was celebrated in John Donne

John Donne ( ; 22 January 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under royal patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's ...

's ''Epithalamion, or Mariage Song on the Lady Elizabeth, and Count Palatine being married on St Valentines Day''.

:Hail Bishop Valentine, whose day this is,

::All the air is thy diocese,

::And all the chirping choristers

:And other birds are thy parishioners

... ...

::The feast, with gluttonous delays,

:Is eaten, and too long their meat they praise,

:The masquers come late, and I think, will stay,

:Like fairies, till the cock crow them away.

:Alas, did not antiquity assign

:A night, as well as day, to thee, O Valentine?

In Donne's ''Epithalamium'', Elizabeth and Frederick were two phoenixs who became one.

Frederick and Elizabeth were called to become prominent Protestant leaders in Europe, and much of the literature performed at the reception carried religious overtones. Literature celebrated the union as "a triumph over the evil of popery". Elizabeth and Frederick were both "zealous Protestants", and the public called upon Frederick to be a leader among the Protestants. Much of the poetry recited at the wedding reception emphasized these political and religious desires, and Frederick was encouraged to become the next great Protestant leader, one that would unite European Protestant countries and bring an end to the Roman Catholic influence.

Three masques at Whitehall

Stars and Statues: The Lord's Masque

After the wedding, on 14 February, a masque byThomas Campion

Thomas Campion (sometimes spelled Campian; 12 February 1567 – 1 March 1620) was an English composer, poet, and physician. He was born in London, educated at Cambridge, studied law in Gray's inn. He wrote over a hundred lute songs, masques ...

was presented in the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace. The patron of ''The Masque of Lords and Honourable Maids'', as John Finet

Sir John Finet or Finett (1571–1641) was the English Master of the Ceremonies in the Stuart court.

Early life

Finet was a son of Robert Finet (d. 1582) of Soulton, near Dover, Kent. His mother was Alice, daughter and coheiress of John Wenloc ...

named it, was Lord Knollys. A woodland scene in the lower part of the stage was revealed, and Orpheus and Mania had a dialogue. Mania and her twelve companion "franticks" danced a "mad measure" and left the stage to Entheus, a distracted poet. He spoke with Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with Jaso ...

, and Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus (; , , possibly meaning " forethought")Smith"Prometheus". is a Titan god of fire. Prometheus is best known for defying the gods by stealing fire from them and giving it to humanity in the form of technology, kn ...

was revealed in the upper part of the stage, with eight masquers dressed as stars on moving clouds designed by Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

.Nichols, ''Progresses'', vol. 2 (London, 1828), pp. 551, 554–7. There was a song, imploring the stars to come on down:

:Large grow their beams, their near approach afford them so

:By nature sights that pleasing are, can not too amply show;

:Oh might these flames in human shapes descend to grace this place,

:How lovely would their presence be, their forms how full of grace!

Sixteen fiery pages with torches danced below, and then waited to attend the male masque star dancers. As these masquers descended in a cloud, the woodland scene changed to reveal four silver women, dancers turned to stone by Jove, in niches built according to the canons of classical architecture but gilded and set with jewels. The statues came to life, and the niches were replenished with another four women, who came to life. The masquers danced two dances together, then drew the bride and groom to dance with them. The scene changed to a classical perspective with gold statues of the couple, and a central obelisk which served as Sybilla's needle. Sybilla delivered her message in Latin, prophesying Elizabeth's imperial destiny in the union of British and German peoples.

Campion's ''Lord's Masque'' was published in 1616. One song from Campion's masque, "Woo her and win her" was separately published with its music, including the lines:

:Woo her and win her, he that can, Each woman hath two lovers;

:So she must take and leave a man, Till time more grace discovers;

:Courtship and music suit with love, They both are works of passion;

:Happy is he whose words can move, Yet sweet notes help persuasion.

Opinions on the performance were mixed. The ambassador Foscarini thought the masque was very beautiful and he was impressed by Inigo Jones' mechanism to make the stars dance. John Chamberlain was not invited to the ''Lord's Masque'', but heard "no great commendation". A wardrobe account includes several items for this masque, costumes for five masquers with speaking parts were made by Thomas Watson.

Further celebrations included the performances of ''The Memorable Masque of the Middle Temple and Lincoln's Inn

''The Memorable Masque of the Middle Temple and Lincoln's Inn'' was a Literature in English#Jacobean literature, Jacobean era masque, written by George Chapman, and with costumes, sets, and stage effects designed by Inigo Jones. It was performed ...

'' by George Chapman

George Chapman (Hitchin, Hertfordshire, – London, 12 May 1634) was an English dramatist, translator and poet. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman has been speculated to be the Rival Poet of Shak ...

, and ''The Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray's Inn

''The Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray's Inn'', also known as, ''The Masque of the Olympic Knights'', is an English masque created in the Jacobean period. It was written by Francis Beaumont and is known to have been performed on 20 February ...

'' by Francis Beaumont. The Temple and the Inns were associations of lawyers in London who trained the sons of aristocrats. Beaumont's masque was set up in the Banqueting Hall but delayed till the 20 February. Chamberlain wrote that entry to these events was not allowed to ladies wearing a farthingale

A farthingale is one of several structures used under Western European women's clothing in the 16th and 17th centuries to support the skirts in the desired shape and enlarge the lower half of the body. It originated in Spain in the fifteenth c ...

, to gain space. Both the Banqueting Hall and the Great Hall already had more scaffolds and temporary seating than usual. Twelve farthingales had been supplied by Robert Hughes for attendants at the wedding, six of taffeta and six of damask with wire and silk, and John Spens made five farthingales of changing taffeta for masque dancers.

Tournament: Running at the Ring

On Monday 15 February there was a tournament of tilting and running at the ring at Whitehall. Anne of Denmark, Elizabeth, and aristocratic women watched from the Banqueting House. King James rode first. The task was the lift a hoop with a spear or lance. Prince Charles did particularly well. The performances of expert riders were appreciated for taking the ring with "much strangeness".Colonialism as entertainment

Chapman's ''Memorable Masque'' was performed in the Great Hall of Whitehall Palace on 15 February. The roof of the hall and its cupola can be seen inWenceslaus Hollar

Wenceslaus Hollar (23 July 1607 – 25 March 1677) was a prolific and accomplished Bohemian graphic artist of the 17th century, who spent much of his life in England. He is known to German speakers as ; and to Czech speakers as . He is particu ...

's engraving of the palace. The masquers arrived in procession and King James made them go around the tilt yard for the benefit of the royal audience. The ''Memorable Masque'' was produced for the Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court – Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have ...

by Edward Phelips Edward Phelips may refer to:

* Sir Edward Phelips (speaker) (c. 1555/60–1614), English lawyer and politician, Speaker of the English House of Common and subsequently Master of the Rolls

* Sir Edward Phelips Jr. (1638–1699), English landowner a ...

, the Master of the Rolls

The Keeper or Master of the Rolls and Records of the Chancery of England, known as the Master of the Rolls, is the President of the Court of Appeal (England and Wales)#Civil Division, Civil Division of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales a ...

and Richard Martin, a lawyer who worked for the Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

, with Christopher Brooke

Christopher Brooke (died 1628) was an English poet, lawyer and politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons between 1604 and 1626.

Life

He was the son of Robert Brooke (16th century MP), Robert Brooke, a rich merchan ...

, and the Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

, Henry Hobart of Blickling

Blickling is a village and civil parish in the Broadland district of Norfolk, England, about north-west of Aylsham. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 136 and covers , falling to 113 at the 2011 Census. Since the 17th century t ...

. Edward Phelips paid Inigo Jones £110 for his work on the masque.

Prince Henry had been George Chapman's patron, and was interested in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, and a settlement Henricus

The "Citie of Henricus"—also known as Henricopolis, Henrico Town or Henrico—was a settlement in Virginia founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1611 as an alternative to the swampy and dangerous area around the original English settlement at Jamest ...

had been named in his honour. Phelips had been Henry's chancellor and was a director of the Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

. Martin Butler detects in the masque the kind of colonial ambition which Henry had preferred, but King James would avoid for its potential for conflict with Spain. Possibly, George Chapman and Francis Beaumont had been preferred as authors in 1612 by Prince Henry, looking for writers sympathetic to his ideals.

The masque represented Virginian peoples on the stage, and introduced the theme of gold mining from Guiana

The Guianas, sometimes called by the Spanish loan-word ''Guayanas'' (''Las Guayanas''), is a region in north-eastern South America which includes the following three territories:

* French Guiana, an overseas department and region of France

* ...

based on the voyages of Walter Ralegh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebellion ...

. Chapman had responded to the promise of Guiana's gold and imperial venture in 1596 with a poem, De Guiana, Carmen Epicum

'. In the poem Chapman outlines a female and Elizabethan England that would be a sibling and a mother to Guiana in "a golden world". A marshal attending the performers and audience, "Baughan", was probably the usher of Anne of Denmark, who had previously fought with Edward Herbert over a hair ribbon worn by a maid of honour, Mary Middlemore. A drawing by

Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

for a torchbearer at the masque, held at Chatsworth, shows a man wearing a feathered head dress, derived partly from a woodcut of Cesare Vecellio

Cesare Vecellio (c. 1521 – c. 1601) was an Italian engraver and painter of the Renaissance, active in Venice.

He was the cousin of the painter Titian. Like Titian, he was born in Cadore in the Veneto. He accompanied Titian to Augsburg in 1548, ...

.

The procession to the palace was led by 50 gentlemen, followed by mock-baboons, actors in Neapolitan suits and great ruffs. The musicians arrived in triumphal cars adorned with mask-heads, festoons, and scrolls. They were dressed as "Virginean priests" with "strange hoods of feathers and scallops about their necks" and "turbans, stuck with several-coloured feathers". The masquers were dressed in "Indian habits" as "Virginian Princes". Their feathers and head attires were bought from a haberdasher, Robert Johns. They wore olive-coloured masks, and their hair was "black and large waving down to their shoulders". Each horse was attended by two "Moores", African servants, who were dressed as Indian slaves. Foscarini wrote that there were 100 Africans, dressed in the blue and gold costume of Indian slaves.

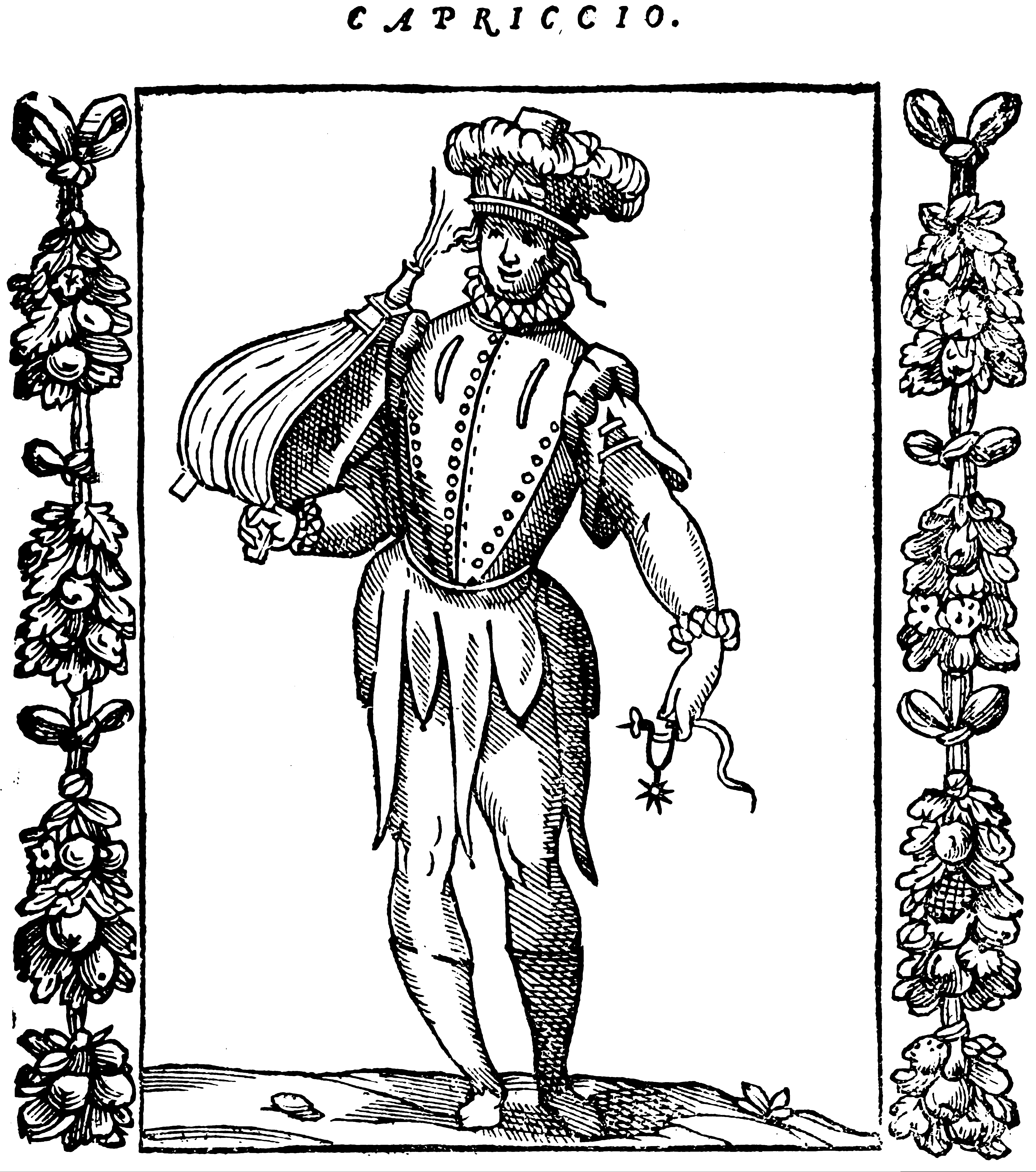

The scene in the hall, designed by Inigo Jones, was a rock with winding staircases visibly veined with gold. On one side was a silver temple of fame, on the other a grove with a vast hollow tree, the resort of baboons. Plutus the deity of wealth spoke, and the rock opened. The Priests sang and a gold mine was revealed. Plutus compared rocks to flinty-hearted ladies. The wit Capriccio entered with bellows, metallurgy in mind, and to swell his head, an image from an emblem

An emblem is an abstract or representational pictorial image that represents a concept, like a moral truth, or an allegory, or a person, like a king or saint.

Emblems vs. symbols

Although the words ''emblem'' and '' symbol'' are often use ...

of Cesare Ripa

Cesare Ripa (c. 1555, Perugia – Rome) was an Italian iconographer who worked for Cardinal Anton Maria Salviati as a cook and butler.

Life

Little is known about his life. He was born of humble origin in Perugia about 1555. The exact date o ...

. He spoke of an island in the South sea, Paena, perhaps Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

although Virginia was commonly called an "isle". Plutus challenged him for stealing from his mine. A troop of baboons entered and danced, then returned to the tree. Honor called forth the Virgin Knights, and so twelve masquers appeared, the "Virginian Princes". The final song was ''A Hymne to Hymen, for the most time-fitted Nuptials of our thrice gracious Princess Elizabeth''.

The masque advocates the religious conversion of the Virginians before the extraction of mineral wealth. "King James and all his company were exceedingly pleased, and especially with their dancing", so Chamberlain heard, and the King praised the Masters of the Inns, "and strokes", or gives "thanks to", "the Master of the Rolls and Dick Martin, who were chief doers and undertakers".

Olympic Knights

Student lawyers at the Inns wrote to their parents for money to contribute to the masques at the wedding.Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

was responsible for Beaumont's masque. The masquers approached the palace on the river (twice, because the exhausted King dismissed them the first time). The Olympic Games were staged for the marriage of Thames and Rhine, on Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (; el, Όλυμπος, Ólympos, also , ) is the highest mountain in Greece. It is part of the Olympus massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located in the Olympus Range on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia, be ...

. Once again, statues encased in gold and silver were returned to life. The next scene was a country May dance with servants and baboons. Then the upper part of the mountain was revealed with two pavilions bedecked with the armoury of fifteen Olympian knights. The knights came down the mountain, danced, and when a song invited each of them to catch a nymph, they danced with ladies from the audience.

On 21 February there was a banquet in a new dining room adjacent to the Whitehall Banqueting House, over the North Terrace. The bill was paid by the Lords who had failed at the running of the ring, each contributing £30. Chamberlain called the venue the new Marriage-Room, which was suitable for dining and dancing. He said the masquers from the Inns of Court were invited (perhaps they dined in Banqueting House). On 22 February King James left London for Theobalds

Theobalds House (also known as Theobalds Palace) in the parish of Cheshunt in the English county of Hertfordshire, was a significant stately home and (later) royal palace of the 16th and early 17th centuries. Set in extensive parkland, it was a r ...

. Anne of Denmark went to Greenwich Palace

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

on 26 February. Charles and the Elector went to Cambridge, and Newmarket where the royal lodging started to subside while James was in bed.

Nothing more was heard of a masque planned by Elizabeth and her entourage, to involve herself and fifteen maidens, mentioned by Antonio Foscarini in October 1612, and probably abandoned after the death of Prince Henry. An account of the festivals published in Heidelberg omits Beaumont's masque and quotes instead in French from what must be Prince Henry's planned masque. This entertainment is now known as the ''Masque of Truth''. It would have been more overtly religious than the others, featuring the union of the world with England in reformed Protestant faith. The Queen of Africa would have been presented to truth personified, Alethiea.

The master of court ceremony, John Finet

Sir John Finet or Finett (1571–1641) was the English Master of the Ceremonies in the Stuart court.

Early life

Finet was a son of Robert Finet (d. 1582) of Soulton, near Dover, Kent. His mother was Alice, daughter and coheiress of John Wenloc ...

later published his observations, which detail the complicated struggles between ambassadors for precedence. He noted a confrontation between the French ambassador's wife and the Scottish Countess of Nottingham, who already enjoyed a reputation for international incidents. As the ambassador's wife was directed to a place at dinner deemed inappropriate by the Countess, she grasped her hand and would not let her go all through the meal.

Departure

There was some controversy over the continued entertainment of Frederick and the expense. On 24 February Anne of Denmark, with Frederick and Elizabeth, attended the christening of the daughter of the Countess of Salisbury. The next day the luxurious coach that Frederick had ordered in Paris arrived. The coach became the responsibility of her Scottish Master of Horse Andrew Keith. Keith later got into a fight at Heidelberg.

On 10 April

There was some controversy over the continued entertainment of Frederick and the expense. On 24 February Anne of Denmark, with Frederick and Elizabeth, attended the christening of the daughter of the Countess of Salisbury. The next day the luxurious coach that Frederick had ordered in Paris arrived. The coach became the responsibility of her Scottish Master of Horse Andrew Keith. Keith later got into a fight at Heidelberg.

On 10 April Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

and Elizabeth travelled from Whitehall to Greenwich, and then to Rochester

Rochester may refer to:

Places Australia

* Rochester, Victoria

Canada

* Rochester, Alberta

United Kingdom

*Rochester, Kent

** City of Rochester-upon-Medway (1982–1998), district council area

** History of Rochester, Kent

** HM Prison ...

. The voyage was delayed, and she went with Prince Charles to Canterbury for a week. Charles returned to London, and Elizabeth and Frederick went to Margate

Margate is a seaside resort, seaside town on the north coast of Kent in south-east England. The town is estimated to be 1.5 miles long, north-east of Canterbury and includes Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay, UK, Palm Bay and Westbrook, Kent, ...

. They sailed on the 26 April on '' The Prince Royal''. Elizabeth left England accompanied by Lady Harington, the Countess of Arundel, and Anne Dudley

Anne Jennifer Dudley (née Beckingham; born 7 May 1956) is an English composer, keyboardist, conductor and pop musician. She was the first BBC Concert Orchestra's Composer in Association in 2001. She has worked in the classical and pop genr ...

as chief lady of honour. James Sandilands was her Master of Household. The other English ships, under the command of the Earl of Nottingham, were ''The Anne Royall'', '' The Repulse'', '' The Red Lion'', '' The Phoenix'', ''The Assurance'', and ''The Disdain'', with the frigate ''Primrose'' two smaller pinnaces ''The George'', a transporter, and ''The Charles''. There were five merchant ships, the ''Triall'', ''William'', ''Dorcas'', and ''Joan''.

The size of Elizabeth's household in Germany had been agreed in October, with 49 posts, but she took many more companions. The whole party numbered 675. A list of her companions includes " Mr Pettye" and "Mr Johnes", Inigo Jones, among the followers of the Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The ...

. Musicians included Richard Gibbons and the harp player Daniel Callander.

Her jeweller Jacob Harderet also made the trip to Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

. Elizabeth had obtained a number of jewels and had to write to Sir Julius Caesar

Sir Julius Caesar (1557/155818 April 1636) was an English lawyer, judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1589 and 1622. He was also known as Julius Adelmare.

Early life and education

Caesar was born near ...

to pay the bill for jewels and rings given as presents at her leave taking in England. She reminded him of the demands of royal etiquette, "You do know that is fitting for my quality at the time of my parting from my natural country to leave some small remembrance of me amongst my affectionate friends, but that any thing employed for my use should remain unpaid doth not well become my quality".

Soon after Elizabeth's departure, Anne of Denmark went to Bath, and at Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

on 4 June was entertained by another representation of a battle with a Turkish galley.

In May the actor-manager John Heminges

John Heminges (bapt. 25 November 1566 – 10 October 1630) was an actor in the King's Men, the playing company for which William Shakespeare wrote. Along with Henry Condell, he was an editor of the First Folio, the collected plays of Shakespeare ...

was paid by the Lord Treasurer for putting on fourteen plays including ''Much Ado About Nothing

''Much Ado About Nothing'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599.See textual notes to ''Much Ado About Nothing'' in ''The Norton Shakespeare'' ( W. W. Norton & Company, 1997 ) p. 1387 The play ...

'' for Elizabeth, Frederick, and Charles at Whitehall. The dates of these performances were not recorded. It is sometimes stated that ''Much Ado About Nothing'' was performed on or near the wedding day, but there is no evidence for this. The other plays at Whitehall mentioned in Heminges' warrant were; ''The Knot of Fools'', ''The Maid's Tragedy'', ''The Merry Devil of Edmonton

''The Merry Devil of Edmonton'' is an Elizabethan-era stage play; a comedy about a magician, Peter Fabell, nicknamed the Merry Devil. It was at one point attributed to William Shakespeare, but is now considered part of the Shakespeare Apocrypha ...

'', '' The Tempest'', ''A King and No King

''A King and No King'' is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher and first published in 1619. It has traditionally been among the most highly praised and popular works in the canon of Fletcher ...

'', ''The Twins Tragedy'', ''The Winter's Tale

''The Winter's Tale'' is a play by William Shakespeare originally published in the First Folio of 1623. Although it was grouped among the comedies, many modern editors have relabelled the play as one of Shakespeare's late romances. Some criti ...

'', ''Sir John Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff is a fictional character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare and is eulogised in a fourth. His significance as a fully developed character is primarily formed in the plays ''Henry IV, Part 1'' and '' Part 2'', wh ...

'', '' The Moor of Venice'', ''The Nobleman'', '' Caesar's Tragedy'', and '' Love Lies a Bleeding''.

Journey to Heidelberg

The fleet arrived at Ostend on 27 April 1613. Maurice, Prince of Orange,Manuel, Hereditary Prince of Portugal

Manuel of Portugal (c. 1568–22 June 1638) was the illegitimate son of António, Prior of Crato, pretender to the Portuguese throne during the 1580 Portuguese succession crisis. He secretly married in 1597 Countess Emilia of Nassau, daughter o ...

, and Henry of Nassau joined them from Vlissingen

Vlissingen (; zea, label=Zeelandic, Vlissienge), historically known in English as Flushing, is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and a city in the southwestern Netherlands on the former island of Walcheren. With its strategic l ...

. The couple were rowed ashore the next day. Princess Elizabeth's female attendants on her arrival at Vlissingen on 29 April 1613 were listed as the Countess of Arundel, Lady Harington, Theodosia, Lady Cecil, Mistress Anne Dudley, Mistress Elizabeth Dudley, Mistress Apsley, and Mistress (Mary) Mayerne.

Vlissingen and Middleburg

Arrangements for the reception of the royal party at Vlissingen andMiddelburg Middelburg may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Europe

* Middelburg, Zeeland, the capital city of the province of Zeeland, southwestern Netherlands

** Roman Catholic Diocese of Middelburg, a former Catholic diocese with its see in the Zeeland ...

were made by the soldier John Throckmorton.William Shaw & G. Dyfnallt Owen, ''HMC 77 Manuscripts of the Viscount De L'Isle'', vol. 5 (London, 1962), pp. 97–108. He was concerned over the details of their arrival by water and landing from "long boats", and found that suitable long boats for such a ceremony were not available. He reported the disappointment of an official, James de Maldere, President of Zeeland

, nl, Ik worstel en kom boven("I struggle and emerge")

, anthem = "Zeeuws volkslied"("Zeelandic Anthem")

, image_map = Zeeland in the Netherlands.svg

, map_alt =

, m ...

, who did not receive a gift from Elizabeth. Throckmorton advised Viscount Lisle

The title of Viscount Lisle has been created six times in the Peerage of England. The first creation, on 30 October 1451, was for John Talbot, 1st Baron Lisle. Upon the death of his son Thomas at the Battle of Nibley Green in 1470, the viscoun ...

to send a jewel or ring with Elizabeth's portrait. Throckmorton's wife Dorothy joined Elizabeth on the journey to Heidelberg.

The Hague

Frederick left forThe Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

. Elizabeth went to Middelburg, then Dort and Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

and rejoined Frederick at The Hague. On 8 May Frederick went ahead to Heidelberg. She received gifts from the States General The word States-General, or Estates-General, may refer to:

Currently in use

* Estates-General on the Situation and Future of the French Language in Quebec, the name of a commission set up by the government of Quebec on June 29, 2000

* States Gener ...

of jewellery, linen, Chinese lacquer

''Toxicodendron vernicifluum'' (formerly ''Rhus verniciflua''), also known by the common name Chinese lacquer tree, is an Asian tree species of genus ''Toxicodendron'' native to China and the Indian subcontinent, and cultivated in regions of C ...

furniture for a cabinet room, and two suites of tapestry woven at the workshop of François Spierincx.

Elizabeth, after a few days went to Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration wit ...

and Haarlem

Haarlem (; predecessor of ''Harlem'' in English) is a city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is the capital of the province of North Holland. Haarlem is situated at the northern edge of the Randstad, one of the most populated metropoli ...

where the city authorities presented her with a cradle and baby-linen. At Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

she was welcomed at an arch depicting Thetis and she was given gold plate. Next she went to Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city and a List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, pro ...

, then Rhenen

Rhenen () is a municipality and a city in the central Netherlands.

The municipality also includes the villages of Achterberg, Remmerden, Elst and Laareind. The town lies at a geographically interesting location, namely on the southernmost par ...

and Arnhem

Arnhem ( or ; german: Arnheim; South Guelderish: ''Èrnem'') is a city and municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands about 55 km south east of Utrecht. It is the capital of the province of Gelderland, located on both banks of ...

. On 20 May she reached Emmerich am Rhein

Emmerich am Rhein ( Low Rhenish and nl, Emmerik) is a city and municipality in the northwest of the German federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The city has a harbour and a quay at the Rhine. In terms of local government organization, it is ...

and then went to Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

, Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

, and Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr r ...

. A report of her journey mentions the seven hills of the Siebengebirge

The (), occasionally Sieben Mountains or Seven Mountains, are a hill range of the German Central Uplands on the east bank of the Middle Rhine, southeast of Bonn.

Description

The area, located in the municipalities of Bad Honnef and König ...

, and a legend that the Devil walks in a castle there, "and holds his Infernal Revels". A story about a castle near Koblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian language, Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman Empire, Roman mili ...

, where a medieval bishop was eaten was by rats, was also included.

Rhine voyage

After a picnic she boarded a luxurious boat on the Rhine, and atBacharach

Bacharach (, also known as ''Bacharach am Rhein'') is a town in the Mainz-Bingen district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' of Rhein-Nahe, whose seat is in Bingen am Rhein, although that town is not withi ...

Frederick joined her. They arrived at Gaulsheim in the Palatinate on 3 June. Here Elizabeth found she had to give gifts to companions now returning to England, and she obtained jewels on credit from Jacob Harderet. At Oppenheim

Oppenheim () is a town in the Mainz-Bingen district of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. The town is a well-known wine center, being the home of the German Winegrowing Museum, and is particularly known for the wines from the Oppenheimer Krötenbru ...

, they took carriages to Frankenthal

Frankenthal (Pfalz) ( pfl, Frongedahl) is a town in southwestern Germany, in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate.

History

Frankenthal was first mentioned in 772. In 1119 an Augustinian monastery was built here, the ruins of which — known, af ...

, where there was a ceremony of Royal Entry. The townspeople dressed as "Turks, Poles, & Switzers" and at night there was a candlelit show of Solomon and Queen of Sheba. The following night's entertainment was the Siege of Troy. Frederick rode on ahead to Heidelberg in order to welcome his bride. Elizabeth arrived on 7 June to a week of elaborate court festival.Green & Lomas (1909), pp. 68–85.

On 13 June there was a tournament of "mad fellows with tubs set on their heads, apparelled all in straw, and sitting on horse back", and the next day the Duke of Lennox, the Earl and Countess of Arundel, and others departed.Edmund Howes, ''Annales, or Generall Chronicle of England'' (London, 1615), p. 923.

References

{{ReflistExternal links

Maria Shmygol, 'A Representation of Algiers in Early Modern London', Medieval and Early Modern Orients

Engraving of the Wedding Procession, attributed to Abraham Hogenberg, Met

Silver gilt commemorative medal with portraits of Elizabeth & Frederick, British Museum

Embarkation at Margate of the Elector Palatine and Princess Elizabeth, Adam Willaerts, RCT

Richard Cavendish, The Marriage of the Winter Queen, History Today

A royal wedding for Valentine's Day, 1613, History of Parliament

Ruth Selman, Royal weddings in history: a Stuart Valentine, The National Archives

Campion's ''The Lord's Masque'', 1613, British Library

'The Winter Queen' Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, V&A

The 1613 Marriage Journey of Elizabeth Stuart, Stanford University Spatial History Project

Court of James VI and I 1613 in England

Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

History of colonialism

Cultural appropriation

English Renaissance plays

1613 plays

Masques

Whitehall