World Museum, Liverpool on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

World Museum is a large

The physical sciences collection of World Museum was built after the devastation caused by the incendiary fire of 1941. The collection has expanded, in part, due to transfers from the Decorative Arts Department, Regional History Department,

The physical sciences collection of World Museum was built after the devastation caused by the incendiary fire of 1941. The collection has expanded, in part, due to transfers from the Decorative Arts Department, Regional History Department,

The Mummy room

The Mummy room

Egypt Exploration Society

, the British School of Archaeology in Egypt, and the Egyptian Research Account between 1884 and 1914. It was further developed through links with the Institute of Archaeology a

Liverpool University

and important collections came to the museum from the excavations of

The reserve collection includes animals from famous naturalists such as

The reserve collection includes animals from famous naturalists such as  There also specimens of several extinct species housed in the museum, including the Liverpool pigeon, the

There also specimens of several extinct species housed in the museum, including the Liverpool pigeon, the

World MuseumLiverpool Planetarium

{{authority control 1853 establishments in England National Museums Liverpool Archaeological museums in England Natural history museums in England Planetaria in the United Kingdom Museums in Liverpool Egyptological collections in England Museums of ancient Rome in the United Kingdom Museums of ancient Greece in the United Kingdom Numismatic museums in the United Kingdom Geology museums in England Insectariums Science museums in England Museums established in 1853 Neoclassical architecture in Liverpool

museum

A museum is an institution dedicated to displaying or Preservation (library and archive), preserving culturally or scientifically significant objects. Many museums have exhibitions of these objects on public display, and some have private colle ...

in Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, England which has extensive collections covering archaeology, ethnology and the natural and physical sciences. Special attractions include the Natural History Centre and a planetarium. Entry to the museum is free. The museum is part of National Museums Liverpool

National Museums Liverpool, formerly National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, comprises several museums and art galleries in and around Liverpool in Merseyside, England. All the museums and galleries in the group have free admission. The mu ...

.

History

The current museum is unconnected to the Liverpool Museum of William Bullock, who operated a museum in his house on Church Street, Liverpool, between 1795 and 1809, before he moved it to London. The museum was originally started as the Derby Museum as it comprised the 13th Earl of Derby'snatural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

collection. It opened in 1851, sharing two rooms on Duke Street with a library. However, the museum proved extremely popular and a new, purpose-built building was required.

Land for the new building, on a street then known as Shaw's Brow (now William Brown Street

William Brown Street in Liverpool, England, is a road that is remarkable for its concentration of public buildings. It is sometimes referred to as the "Cultural Quarter".

Originally known as ''Shaw's Brow'', a coaching road east from the city, ...

), opposite St George's Hall, was donated by a local MP and wealthy merchant, Sir William Brown, as was much of the funding for the building which would be known as the William Brown Library and Museum

The William Brown Library and Museum is a Grade II* listed building situated on the historic William Brown Street in Liverpool, England. The building currently houses part of the World Museum Liverpool and Liverpool Central Library.

The Will ...

. Around 400,000 people attended the opening of the new building in 1860.

Reports detailing the museum's activities and acquisitions were presented to the committee of the borough, city and corporation of Liverpool annually.

In the late 19th century, the museum's collection was beginning to outgrow its building so a competition was launched to design a combined extension to the museum and college of technology. The competition was won by Edward William Mountford

Edward William Mountford (22 September 1855 – 7 February 1908) was an English architect, noted for his Edwardian Baroque architecture, Edwardian Baroque style, who designed a number of town halls – Sheffield, Battersea and Lancaster – as ...

and the College of Technology and Museum Extension

The College of Technology and Museum Extension on Byrom Street in Liverpool, England, was built between 1896 and 1909, the architect was Edward William Mountford. The building was constructed to provide a new College of Technology and an exten ...

opened in 1901.

Liverpool, being one of the UK's major ports, was heavily damaged by German bombing during the blitz

Blitz, German for "lightning", may refer to:

Military uses

*Blitzkrieg, blitz campaign, or blitz, a type of military campaign

*The Blitz, the German aerial campaign against Britain in the Second World War

*, several ships of the Prussian, Imperia ...

. While much of the museum's collection was moved to less vulnerable locations during the war, the museum building was struck by German firebombs and suffered heavy damage. Parts of the museum only began to reopen fifteen years later. One of the exhibits destroyed in 1941 was the little yawl

A yawl is a type of boat. The term has several meanings. It can apply to the rig (or sailplan), to the hull type or to the use which the vessel is put.

As a rig, a yawl is a two masted, fore and aft rigged sailing vessel with the mizzen mast ...

''City of Ragusa

''City of Ragusa'' of Liverpool was a yawl (in 19th-century terms), owned by Nikola Primorac, which twice crossed the Atlantic in the early days of 19th-century small-boat ocean-adventuring. She carried the former alternative name of Dubrovnik, ...

'', which twice crossed the Atlantic in 1870 and 1871 with a crew of two men.

The museum underwent a £35 million refurbishment in 2005 in order to double the size of the display spaces and make more of the collections accessible for visitors. A central entrance hall and six-storey atrium were created as part of the work. Major new galleries included "World Cultures", the "Bug House" and the "Weston Discovery Centre". On reopening the museum's name was changed again to World Museum.

Collections and exhibits

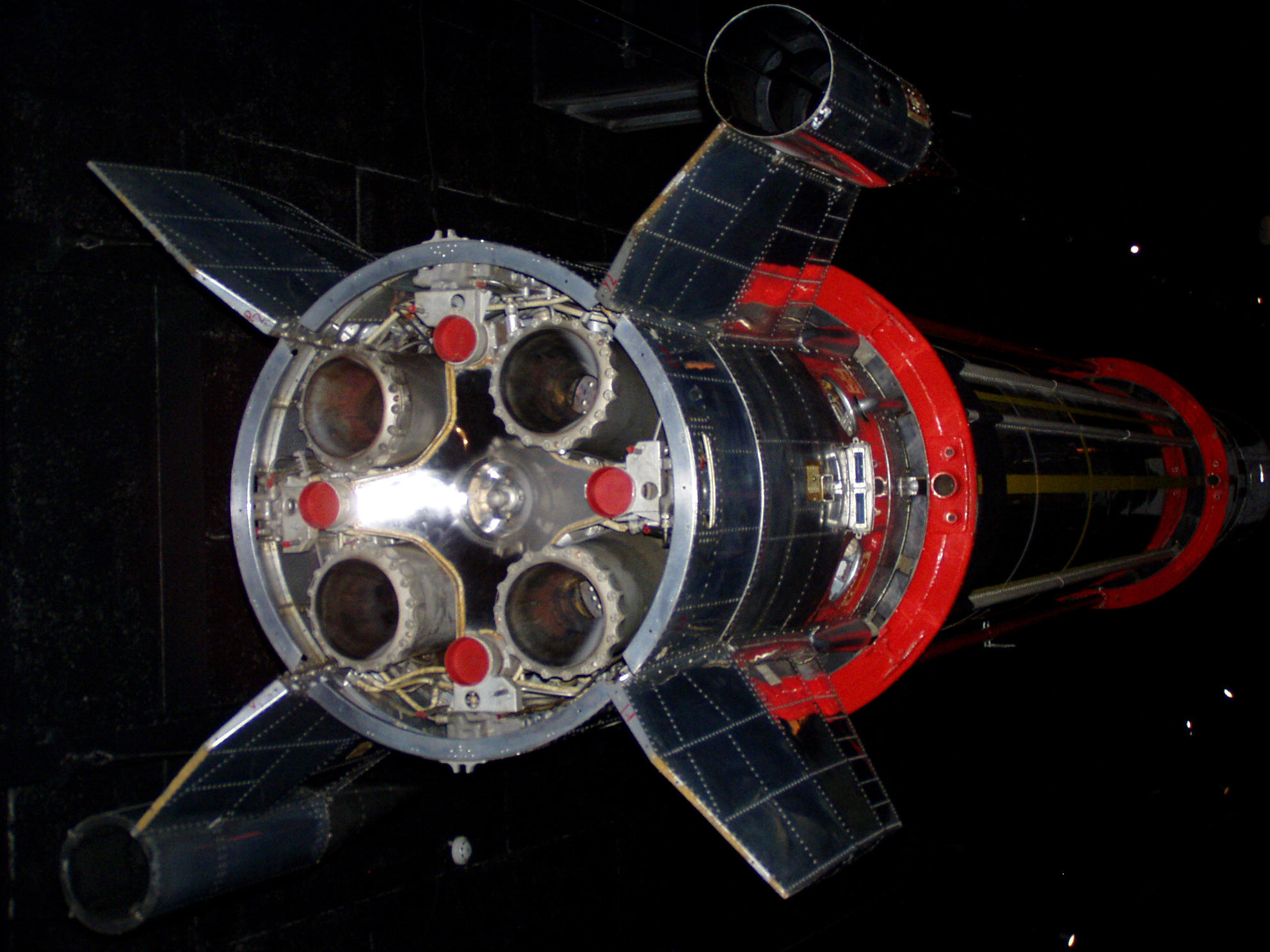

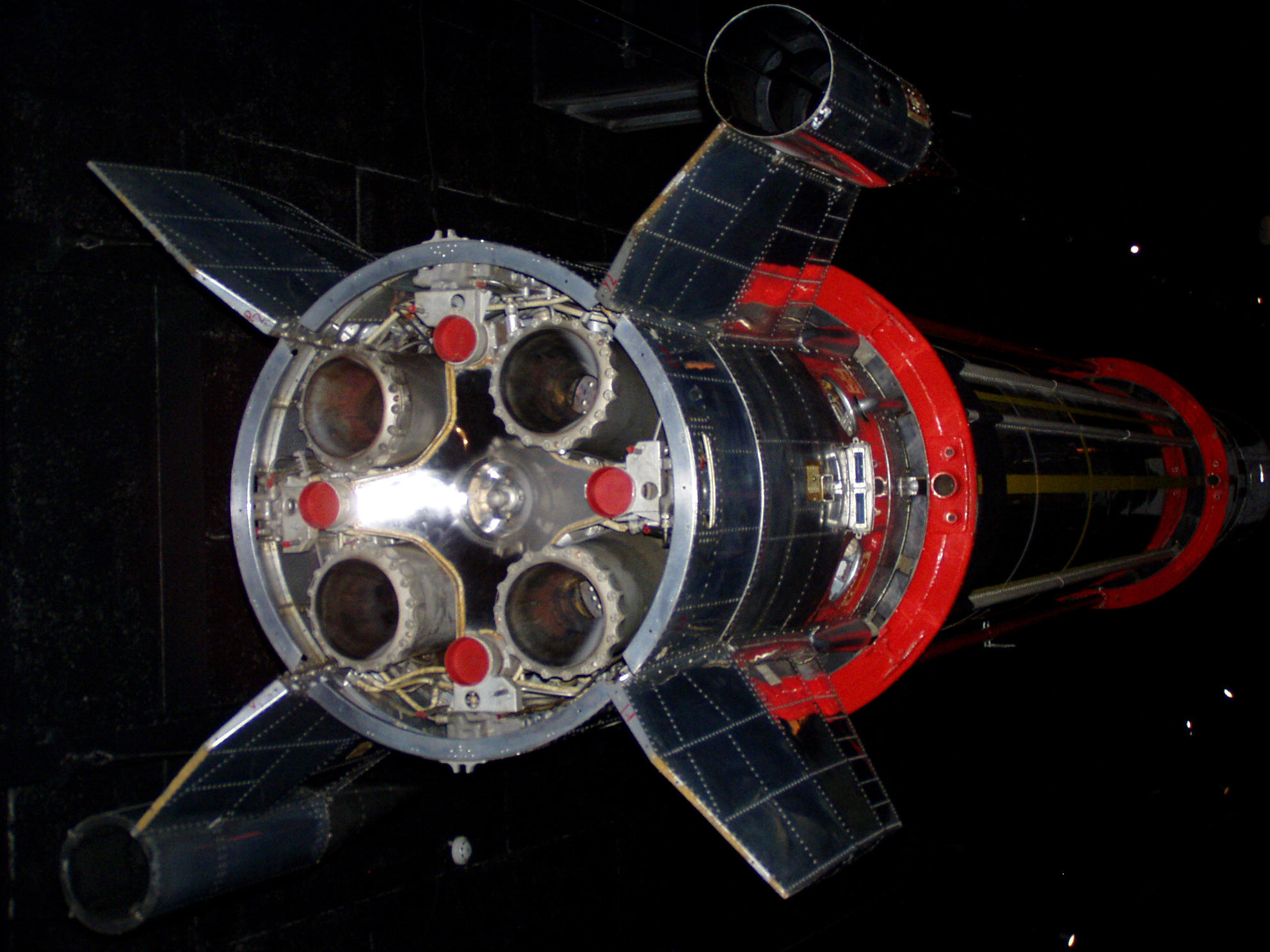

Astronomy, space and time

The physical sciences collection of World Museum was built after the devastation caused by the incendiary fire of 1941. The collection has expanded, in part, due to transfers from the Decorative Arts Department, Regional History Department,

The physical sciences collection of World Museum was built after the devastation caused by the incendiary fire of 1941. The collection has expanded, in part, due to transfers from the Decorative Arts Department, Regional History Department, Walker Art Gallery

The Walker Art Gallery is an art gallery in Liverpool, which houses one of the largest art collections in England outside London. It is part of the National Museums Liverpool group.

History

The Walker Art Gallery's collection dates from 1819 ...

and the Prescot Museum. The collection also contains several significant collections from the Liverpool Royal Institution, Bidston Observatory, later the Proudman Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, and the Physics Department of the University of Liverpool.

Collections such as these are often made up of items of a singular type designed for a particular experiment such as DELPHI or LEP at CERN

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN (; ; ), is an intergovernmental organization that operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Established in 1954, it is based in Meyrin, western suburb of Gene ...

– the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or the Equatorium

An equatorium (plural, equatoria) is an astronomy, astronomical Mechanical calculator, calculating instrument. It can be used for finding the positions of the Moon, Sun, and planets without arithmetic operations, using a geometrical model to re ...

, a post-Copernican planetary calculator made to special order in the early 17th century. As a consequence the collection is small but contains a number of significant items.

Planetarium

World Museum is home to aplanetarium

A planetarium (: planetariums or planetaria) is a theatre built primarily for presenting educational and entertaining shows about astronomy and the night sky, or for training in celestial navigation.

A dominant feature of most planetariums is ...

. The planetarium, said to be the first planetarium in the UK outside of London, opened in 1970 and has 62 seats. It currently attracts about 90,000 people per year. Shows cover various aspects of space science, including the Solar System and space exploration; there are also special children's shows.

Human history

The Mummy room

The Mummy room

Archaeology and Egyptology

The archaeological collection includes many fine British objects, including the Anglo-Saxon Kingston brooch andLiudhard medalet

The Liudhard medalet is a gold Anglo-Saxon coin or small medal found sometime before 1844 near St Martin's Church in Canterbury, England. It was part of the Canterbury-St Martin's hoard of six items. The coin, along with other items found with ...

, with other objects from the Canterbury-St Martin's hoard

The Canterbury-St Martin's hoard is a coin-hoard dating from the 6th century, found in the 19th century at Canterbury, Kent. The group, in the World Museum, Liverpool, consists of eight items, including three gold coins mounted with suspensio ...

.

The Egyptian antiquities collection contains approximately 15,000 objects from Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

and is the most important single component of the Antiquities department's collections. The chronological range of the collection spans from the Prehistoric to the Islamic Period with the largest archaeological site collections being Abydos, Amarna

Amarna (; ) is an extensive ancient Egyptian archaeological site containing the ruins of Akhetaten, the capital city during the late Eighteenth Dynasty. The city was established in 1346 BC, built at the direction of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, and a ...

, Beni Hasan

Beni Hasan (also written as Bani Hasan, or also Beni-Hassan) () is an ancient Egyptian cemetery. It is located approximately to the south of modern-day Minya in the region known as Middle Egypt, the area between Asyut and Memphis.Baines, John ...

, Esna

Esna ( , or ; ''Snē'' from ''tꜣ-snt''; ''Latópolis'' or (''Pólis Látōn'') or (''Lattōn''); Latin: ''Lato'') is a city of Egypt. It is located on the west bank of the Nile some south of Luxor. The city was formerly part of the ...

and Meroe.

Over 5,000 Egyptian antiquities were donated to the museum in 1867 by Joseph Mayer (1803–1886), a local goldsmith and antiquarian. Mayer purchased collections from Joseph Sams of Darlington (which contained material from the Henry Salt sale in 1835), Lord Valentia, Bram Hertz, the Reverend Henry Stobart, and the heirs of the Rev. Bryan Faussett

Bryan Faussett (30 October 1720 – 20 February 1776) was an English antiquary. Faussett formed a collection that was rich in Anglo-Saxon objects of personal adornment, such as pendants, brooches, beads and buckles. He discovered the Kingston B ...

. Mayer had displayed his collection in his own ‘Egyptian Museum’ in Liverpool with a purpose of giving citizens who were unable to visit the British Museum in London some idea of the achievements of the Egyptian civilization. On the strength of this substantial donation other people began to donate Egyptian material to the museum, and by the later years of the 19th century the museum had a substantial collection that Amelia Edwards

Amelia Ann Blanford Edwards (7 June 1831 – 15 April 1892), also known as Amelia B. Edwards, was an English novelist, journalist, traveller and Egyptologist. Her literary successes included the ghost story ''The Phantom Coach'' (1864), the nov ...

described as being the most important collection of Egyptian antiquities in England next to the contents of the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

.

The quality of the Mayer donation is high and there are some outstanding items, but with a few exceptions the entire collection is unprovenanced. The collection was systematically enhanced through subscription to excavations in Egypt. Altogether the museum subscribed to 25 excavations carried out by the Egypt Exploration Fund

The Egypt Exploration Society (EES) is a British non-profit organization founded in 1882 for the purpose of financing and facilitating the exploration of significant archeological sites in Egypt and Sudan, founded by writer Amelia Edwards and coin ...

(noEgypt Exploration Society

, the British School of Archaeology in Egypt, and the Egyptian Research Account between 1884 and 1914. It was further developed through links with the Institute of Archaeology a

Liverpool University

and important collections came to the museum from the excavations of

John Garstang

John Garstang (5 May 1876 – 12 September 1956) was a British archaeologist of the Ancient Near East, especially Egypt, Sudan, Anatolia and the southern Levant. He was the younger brother of Professor Walter Garstang, FRS, a marine biol ...

who was honorary reader in Egyptian archaeology at Liverpool University, 1902–1907, and Professor of Methods and Practice of Archaeology, 1907–1941. The museum has always had a close relationship with the university; in the early 1920s Percy Newberry

Percy Edward Newberry (23 April 1869 – 7 August 1949) was a British Egyptologist.

Biography

Percy Newberry was born in Islington, London on 23 April 1869. His parents were Caroline () and Henry James Newberry, a woollen warehouseman. Newbe ...

, Brunner Professor of Egyptology Brunner may refer to:

Places

* Brunner, New Zealand

* Lake Brunner, New Zealand

* Brunner Mine, New Zealand

* Brunner, Houston, United States

* Brunner (crater), lunar crater

Other uses

* Brunner (surname)

* Brunner the Bounty Hunter, a character ...

, and his successor T. Eric Peet, catalogued the collection, assisted with the rearrangement of the displays, and produced a handbook and guide to the Egyptian collection (1st ed., 1923).

In May 1941, at the height of the Liverpool Blitz

The Liverpool Blitz was the The Blitz, heavy and sustained bombing of the British city of Liverpool and its surrounding area, during the Second World War by the Nazi Germany, German ''Luftwaffe''.

Liverpool was the most heavily bombed area o ...

, a bomb fell on the museum, which was burnt to a shell. Large parts of the collection had been removed at the outbreak of the war, but much remained on display or in store and many artefacts were destroyed. What remained was quite inaccessible and it was not until 1976 that a permanent Egypt gallery was opened in the rebuilt museum. Following the war the museum actively augmented the collection through collecting of new material from excavations in Egypt and Sudan and the purchase of other museum collections. In 1947 and 1949 the material from Garstang's excavations at Meroe came to the museum, and in 1955 Liverpool University placed substantial amounts from its own collections within the museum, including many items from Beni Hasan and Abydos. In 1956 the museum purchased almost the entire non-British collections of the Norwich Castle Museum

Norwich Castle is a medieval royal fortification in the city of Norwich, in the English county of Norfolk. William the Conqueror (1066–1087) ordered its construction in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England. The castle was used as a ...

. This included EES excavated material from Amarna and other sites, botanical remains from Kahun and the private collection of Sir Henry Rider Haggard

Sir Henry Rider Haggard (; 22 June 1856 – 14 May 1925) was an English writer of adventure fiction romances set in exotic locations, predominantly Africa, and a pioneer of the lost world literary genre. He was also involved in land reform t ...

. In 1973 the collection was increased further by the acquisition of part of the Sir Henry Wellcome Collection, and by the bequest of Colonel J. R. Danson in 1976, which included more material from Amarna and from Garstang's excavations at Abydos.

Postwar a limited Egyptian gallery was opened in 1976 before being expanded in 2008. The gallery between September 2015 and April 2017 to allow it to be improved and expanded.

A handy lavishly illustrated guide to the collection is available: ''Gifts of the Nile'' (London: HMSO, 1995).

Ethnology

Theethnology

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).

Sci ...

collection at World Museum ranks among the top six collections in the country. The four main areas represented are: Africa, the Americas, Oceania and Asia. The exhibition includes interactive

Across the many fields concerned with interactivity, including information science, computer science, human-computer interaction, communication, and industrial design, there is little agreement over the meaning of the term "interactivity", but mo ...

displays.

Natural history

In the Natural World area can be seen a range of exhibits, including live colonies of insects and historiczoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

and botanical

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

exhibits. Visitors can examine the collections up close in the award-winning Clore Natural History Centre, where there are interactive displays.

World Museum's natural history collection is divided into the Botany, Entomology and other Invertebrates, Geology and Vertebrate Zoology collections.

Vertebrate zoology

The13th Earl of Derby

Edward Smith-Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby (21 April 1775 – 30 June 1851), styled Lord Stanley from 1776 to 1832, and Baron Stanley of Bickerstaffe from 1832–4, was an English politician, peer, landowner, builder, farmer, art collector and na ...

founded the original museum with a major donation of zoological specimens in 1851, including many rare and 'type

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* ...

' specimens, the ones that act as standards for the species, animals that died in the Knowsley menagerie, and specimens purchased at major sales (e.g. Leverian collection

The Leverian collection was a natural history and ethnographic collection assembled by Ashton Lever. It was noted for the content it acquired from the voyages of Captain James Cook. For three decades it was displayed in London, being broken up ...

). The vertebrate zoology collection was vastly increased with the purchase of Canon Henry Baker Tristram's collection of birds in 1896.

The reserve collection includes animals from famous naturalists such as

The reserve collection includes animals from famous naturalists such as Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

, John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin, April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was a French-American Autodidacticism, self-trained artist, natural history, naturalist, and ornithology, ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornitho ...

, William Thomas March, John Whitehead and Stamford Raffles

Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (5 July 1781 – 5 July 1826) was a British Colonial Office, colonial official who served as the List of governors of the Dutch East Indies, governor of the Dutch East Indies between 1811 and 1816 and lieut ...

, transfers from other museums (Selangor Museum

Selangor ( ; ), also known by the Arabic honorific Darul Ehsan, or "Abode of Sincerity", is one of the 13 states of Malaysia. It is on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia and is bordered by Perak to the north, Pahang to the east, Negeri Sembi ...

, India Museum

The India Museum was a London museum of India-related exhibits, established in 1801. It was closed in 1879 and its collection dispersed, part of it later forming a section in the South Kensington Museum.

History

The museum, of the East India Co ...

), circuses (Barnum and Bailey

The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, also known as the Ringling Bros. Circus, Ringling Bros., the Barnum & Bailey Circus, Barnum & Bailey, or simply Ringling, is an American traveling circus company billed as The Greatest Show on Earth ...

) and zoos (Southport Zoological Gardens, Chester Zoo

Chester Zoo is a zoo in Upton-by-Chester, Cheshire, England. Chester Zoo was opened in 1931 by George Mottershead and his family. The zoo is one of the UK's largest zoos at and the zoo has a total land holding of approximately .

Chester Zoo ...

); and collections from the museum's expeditions.

There also specimens of several extinct species housed in the museum, including the Liverpool pigeon, the

There also specimens of several extinct species housed in the museum, including the Liverpool pigeon, the great auk

The great auk (''Pinguinus impennis''), also known as the penguin or garefowl, is an Extinction, extinct species of flightless bird, flightless auk, alcid that first appeared around 400,000 years ago and Bird extinction, became extinct in the ...

(an egg), the Falkland Islands wolf

The Falkland Islands wolf (''Dusicyon australis'') was the only native land mammal of the Falkland Islands. This endemic canid became extinct in 1876, the first known canid to have become extinct in historical times.

Traditionally, it had been ...

, the South Island piopio

The South Island piopio (''Turnagra capensis'') also known as the New Zealand thrush, is an extinct species of passerine bird of the family Oriolidae. Milford Sound in the South Island of New Zealand is known as Piopiotahi in te reo Māori.

...

, the Lord Howe swamphen, the Passenger pigeon

The passenger pigeon or wild pigeon (''Ectopistes migratorius'') is an bird extinction, extinct species of Columbidae, pigeon that was endemic to North America. Its common name is derived from the French word ''passager'', meaning "passing by" ...

, the dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinction, extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest relative was the also-extinct and flightles ...

, the Pink-headed duck

The pink-headed duck (''Rhodonessa caryophyllacea'') is a large diving duck that was once found in parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, Gangetic plains of India, Nepal, parts of Maharashtra, Bangladesh and in the riverine swamps of Myanmar but has b ...

, the Norfolk kākā

The Norfolk kākā (''Nestor productus'') is an extinct species of large parrot, belonging to the parrot family Nestoridae. The birds were about 38 cm long, with mostly olive-brown upperparts, reddish-orange cheeks and throat, straw-colour ...

, the Stephens Island wren, the Bushwren

The bushwren (''Xenicus longipes''), also known as the in the Māori language, is an extinct species of diminutive and nearly flightless bird that was endemic to New Zealand. It had three subspecies on each of the major islands of New Zealand, ...

, the Carolina Parakeet

The Carolina parakeet (''Conuropsis carolinensis''), or Carolina conure, is an extinct species of small green neotropical parrot with a bright yellow head, reddish orange face, and pale beak that was native to the Eastern, Midwest, and Plains ...

, the Cuban Macaw

The Cuban macaw or Cuban red macaw (''Ara tricolor'') is an extinct species of macaw native to the main island of Cuba and the nearby Isla de la Juventud. It became extinct in the late 19th century. Its relationship with other macaws in its genu ...

, the long-tailed hopping mouse

The long-tailed hopping mouse (''Notomys longicaudatus'') is an extinct species of rodent in the family Muridae. It was found only in Australia. It is known from a handful of specimens, the last of which was collected in 1901 or possibly 1902. It ...

and the thylacine

The thylacine (; binomial name ''Thylacinus cynocephalus''), also commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, was a carnivorous marsupial that was native to the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmani ...

.

The museum had extensive public galleries containing vertebrate taxidermy specimens, but these were lost when during the air raids of May 1941 the building was completely destroyed by fire. Some mammal specimens from the original 13th Earl of Derby

Edward Smith-Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby (21 April 1775 – 30 June 1851), styled Lord Stanley from 1776 to 1832, and Baron Stanley of Bickerstaffe from 1832–4, was an English politician, peer, landowner, builder, farmer, art collector and na ...

collection did survive, along with most of the cabinet bird skins. The galleries featured an exhibition of British mammals, amphibians and reptiles, with several cases imaged in 1932.

The British Birds Gallery featured 131 cases, with several cases imaged between 1914 and 1932. These were the work of taxidermist Mr. J. W. Cutmore who would later produce a series of well-known dioramas at Norwich Museum.

The current natural history gallery is called ''Endangered Planet'' and features a limited number of taxidermy

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body by mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word ''taxidermy'' describes the proces ...

vertebrates in four diorama representing biomes

A biome () is a distinct geographical region with specific climate, vegetation, and animal life. It consists of a biological community (ecology), community that has formed in response to its physical environment and regional climate. In 1935, Art ...

, savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) biome and ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach th ...

, tropical rainforest

Tropical rainforests are dense and warm rainforests with high rainfall typically found between 10° north and south of the Equator. They are a subset of the tropical forest biome that occurs roughly within the 28° latitudes (in the torrid zo ...

, taiga

Taiga or tayga ( ; , ), also known as boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces, and larches. The taiga, or boreal forest, is the world's largest land biome. In North A ...

, tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

. The gallery can be visited virtually.

Botany

The museum's collections have grown considerably since then and now also include important botanical specimens dating back over 200 years, which represent most of Britain and Ireland's native flora. The museum had a gallery of economic botany which was destroyed during the air raids of May 1941.Geology

The time tunnel gallery displays a series of models across geological time. The geological collection at World Museum contains over 40,000 fossils as well as extensive rock and mineral collections. Each of these exhibits show information about the origins, structure and history of the planet earth. Founded in 1858, only seven years after the museum's establishment, much of the original collection was destroyed during the Second World War. The post-war collections have expanded considerably, thanks in part to the acquisition of several significant museum and university collections. The largest of these was theUniversity of Liverpool

The University of Liverpool (abbreviated UOL) is a Public university, public research university in Liverpool, England. Founded in 1881 as University College Liverpool, Victoria University (United Kingdom), Victoria University, it received Ro ...

's geological collection that includes some 6,600 fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

specimens. The collection covers the following areas: palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

, rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wale ...

s and

minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): M ...

.

Facial recognition system

Facial recognition technology, widespread in China, was used at Liverpool's World Museum, during the China's First Emperor and the Terracotta Warriors exhibition. The museum claimed the scanning equipment was used on the advice of local police (Merseyside Police

Merseyside Police is the territorial police force responsible for policing Merseyside in North West England. The service area is 647 square kilometres with a population of around 1.5 million. As of September 2017 the service has 3,484 police o ...

), not the Chinese lenders. In a statement, the director of Big Brother Watch

Big Brother Watch is a non-party British civil liberties and privacy campaigning organisation. It was launched in 2009 by founding director Alex Deane to campaign against state surveillance and threats to civil liberties. It was founded by Ma ...

, Silkie Carlo, said that the "authoritarian surveillance tool is rarely seen outside of China."

Notes and references

External links

World Museum

{{authority control 1853 establishments in England National Museums Liverpool Archaeological museums in England Natural history museums in England Planetaria in the United Kingdom Museums in Liverpool Egyptological collections in England Museums of ancient Rome in the United Kingdom Museums of ancient Greece in the United Kingdom Numismatic museums in the United Kingdom Geology museums in England Insectariums Science museums in England Museums established in 1853 Neoclassical architecture in Liverpool