word form on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

Introduction – 2 Syntax and morphosyntax: some basic notions

' in Dufter, Andreas, and Stark, Elisabeth (eds., 2017)

Manual of Romance Morphosyntax and Syntax

', Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG the term is also used to underline the fact that syntax and morphology are interrelated.Van Valin, R. D., van Valin Jr, R. D., van Valin Jr, R. D., LaPolla, R. J., & LaPolla, R. J. (1997)

Syntax: Structure, meaning, and function

', p.2, Cambridge University Press. The study of morphosyntax concerns itself with inflection and paradigms, and some approaches to morphosyntax exclude from its domain the phenomena of word formation, compounding, and derivation. Within morphosyntax fall the study of agreement and

In morpheme-based morphology, word forms are analyzed as arrangements of

In morpheme-based morphology, word forms are analyzed as arrangements of

Lecture 7 Morphology

in Linguistics 001 by Mark Liberman, ling.upenn.edu

Intro to Linguistics – Morphology

by Jirka Hana, ufal.mff.cuni.cz

by Stephen R. Anderson, part of Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, cowgill.ling.yale.edu

Introduction to Linguistic Theory – Morphology: The Words of Language

by Adam Szczegielniak, scholar.harvard.edu

LIGN120: Introduction to Morphology

by Farrell Ackerman and Henry Beecher, grammar.ucsd.edu

by P. J. Hancox, cs.bham.ac.uk {{Authority control Linguistics terminology Grammar

linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

, morphology is the study of word

A word is a basic element of language that carries semantics, meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible. Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguist ...

s, including the principles by which they are formed, and how they relate to one another within a language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

. Most approaches to morphology investigate the structure of words in terms of morpheme

A morpheme is any of the smallest meaningful constituents within a linguistic expression and particularly within a word. Many words are themselves standalone morphemes, while other words contain multiple morphemes; in linguistic terminology, this ...

s, which are the smallest units in a language with some independent meaning. Morphemes include root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

s that can exist as words by themselves, but also categories such as affix

In linguistics, an affix is a morpheme that is attached to a word stem to form a new word or word form. The main two categories are Morphological derivation, derivational and inflectional affixes. Derivational affixes, such as ''un-'', ''-ation' ...

es that can only appear as part of a larger word. For example, in English the root ''catch'' and the suffix ''-ing'' are both morphemes; ''catch'' may appear as its own word, or it may be combined with ''-ing'' to form the new word ''catching''. Morphology also analyzes how words behave as parts of speech, and how they may be inflected

In linguistic Morphology (linguistics), morphology, inflection (less commonly, inflexion) is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical category, grammatical categories such as grammatical tense, ...

to express grammatical categories including number

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

, tense, and aspect. Concepts such as productivity

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production proce ...

are concerned with how speakers create words in specific contexts, which evolves over the history of a language.

The basic fields of linguistics broadly focus on language structure at different "scales". Morphology is considered to operate at a scale larger than phonology

Phonology (formerly also phonemics or phonematics: "phonemics ''n.'' 'obsolescent''1. Any procedure for identifying the phonemes of a language from a corpus of data. 2. (formerly also phonematics) A former synonym for phonology, often pre ...

, which investigates the categories of speech sounds that are distinguished within a spoken language, and thus may constitute the difference between a morpheme and another. Conversely, syntax

In linguistics, syntax ( ) is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituenc ...

is concerned with the next-largest scale, and studies how words in turn form phrases and sentences. Morphological typology

Morphological typology is a linguistic typology, way of classifying the languages of the world that groups languages according to their common Morphology (linguistics), morphological structures. The field organizes languages on the basis of how ...

is a distinct field that categorises languages based on the morphological features they exhibit.

History

The history of ancient Indian morphological analysis dates back to the linguistPāṇini

(; , ) was a Sanskrit grammarian, logician, philologist, and revered scholar in ancient India during the mid-1st millennium BCE, dated variously by most scholars between the 6th–5th and 4th century BCE.

The historical facts of his life ar ...

, who formulated the 3,959 rules of Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

morphology in the text ''Aṣṭādhyāyī

The (; ) is a grammar text that describes a form of the Sanskrit language.

Authored by the ancient Sanskrit scholar Pāṇini and dated to around 6th c. bce, 6-5th c.BCE and 4th c.BCE, it describes the language as current in his time, specifica ...

'' by using a constituency grammar. The Greco-Roman grammatical tradition also engaged in morphological analysis. Studies in Arabic morphology, including the ''Marāḥ Al-Arwāḥ'' of Aḥmad b. 'Alī Mas'ūd, date back to at least 1200 CE.

The term "morphology" was introduced into linguistics by August Schleicher

August Schleicher (; 19 February 1821 – 6 December 1868) was a German linguist. Schleicher studied the Proto-Indo-European language and devised theories concerning historical linguistics. His great work was ''A Compendium of the Comparative Gr ...

in 1859.

Fundamental concepts

Lexemes and word-forms

The term "word" has no well-defined meaning. Instead, two related terms are used in morphology:lexeme

A lexeme () is a unit of lexical meaning that underlies a set of words that are related through inflection. It is a basic abstract unit of meaning, a unit of morphological analysis in linguistics that roughly corresponds to a set of forms ta ...

and word-form. Generally, a lexeme is a set of inflected word-forms that is often represented with the citation form

In morphology and lexicography, a lemma (: lemmas or lemmata) is the canonical form, dictionary form, or citation form of a set of word forms. In English, for example, ''break'', ''breaks'', ''broke'', ''broken'' and ''breaking'' are forms of the ...

in small capitals. For instance, the lexeme contains the word-forms ''eat, eats, eaten,'' and ''ate''. ''Eat'' and ''eats'' are thus considered different word-forms belonging to the same lexeme . ''Eat'' and ''Eater'', on the other hand, are different lexemes, as they refer to two different concepts.

Prosodic word vs. morphological word

Here are examples from other languages of the failure of a single phonological word to coincide with a single morphological word form. InLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, one way to express the concept of 'NOUN-PHRASE1 and NOUN-PHRASE2' (as in "apples and oranges") is to suffix '-que' to the second noun phrase: "apples oranges-and". An extreme level of the theoretical quandary posed by some phonological words is provided by the Kwak'wala language. In Kwak'wala, as in a great many other languages, meaning relations between nouns, including possession and "semantic case", are formulated by affixes, instead of by independent "words". The three-word English phrase, "with his club", in which 'with' identifies its dependent noun phrase as an instrument and 'his' denotes a possession relation, would consist of two words or even one word in many languages. Unlike most other languages, Kwak'wala semantic affixes phonologically attach not to the lexeme they pertain to semantically but to the preceding lexeme. Consider the following example (in Kwak'wala, sentences begin with what corresponds to an English verb):

That is, to a speaker of Kwak'wala, the sentence does not contain the "words" 'him-the-otter' or 'with-his-club' Instead, the markers -''i-da'' (PIVOT-'the'), referring to "man", attaches not to the noun ''bəgwanəma'' ("man") but to the verb; the markers -''χ-a'' (ACCUSATIVE-'the'), referring to ''otter'', attach to ''bəgwanəma'' instead of to ''q'asa'' ('otter'), etc. In other words, a speaker of Kwak'wala does not perceive the sentence to consist of these phonological words:

A central publication on this topic is the volume edited by Dixon and Aikhenvald (2002), examining the mismatch between prosodic-phonological and grammatical definitions of "word" in various Amazonian, Australian Aboriginal, Caucasian, Eskimo, Indo-European, Native North American, West African, and sign languages. Apparently, a wide variety of languages make use of the hybrid linguistic unit clitic

In morphology and syntax, a clitic ( , backformed from Greek "leaning" or "enclitic"Crystal, David. ''A First Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics''. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1980. Print.) is a morpheme that has syntactic characteristics of a ...

, possessing the grammatical features of independent words but the prosodic

In linguistics, prosody () is the study of elements of speech, including intonation (linguistics), intonation, stress (linguistics), stress, Rhythm (linguistics), rhythm and loudness, that occur simultaneously with individual phonetic segments: v ...

-phonological lack of freedom of bound morpheme

In linguistics, a bound morpheme is a morpheme (the elementary unit of morphosyntax) that can appear only as part of a larger expression, while a free morpheme (or unbound morpheme) is one that can stand alone. A bound morpheme is a type of bound f ...

s. The intermediate status of clitics poses a considerable challenge to linguistic theory.

Inflection vs. word formation

Given the notion of a lexeme, it is possible to distinguish two kinds of morphological rules. Some morphological rules relate to different forms of the same lexeme, but other rules relate to different lexemes. Rules of the first kind areinflection

In linguistic Morphology (linguistics), morphology, inflection (less commonly, inflexion) is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical category, grammatical categories such as grammatical tense, ...

al rules, but those of the second kind are rules of word formation. The generation of the English plural ''dogs'' from ''dog'' is an inflectional rule, and compound phrases and words like ''dog catcher'' or ''dishwasher'' are examples of word formation. Informally, word formation rules form "new" words (more accurately, new lexemes), and inflection rules yield variant forms of the "same" word (lexeme).

The distinction between inflection and word formation is not at all clear-cut. There are many examples for which linguists fail to agree whether a given rule is inflection or word formation. The next section will attempt to clarify the distinction.

Word formation includes a process in which one combines two complete words, but inflection allows the combination of a suffix with a verb to change the latter's form to that of the subject of the sentence. For example: in the present indefinite, 'go' is used with subject I/we/you/they and plural nouns, but third-person singular pronouns (he/she/it) and singular nouns causes 'goes' to be used. The '-es' is therefore an inflectional marker that is used to match with its subject. A further difference is that in word formation, the resultant word may differ from its source word's grammatical category, but in the process of inflection, the word never changes its grammatical category.

Types of word formation

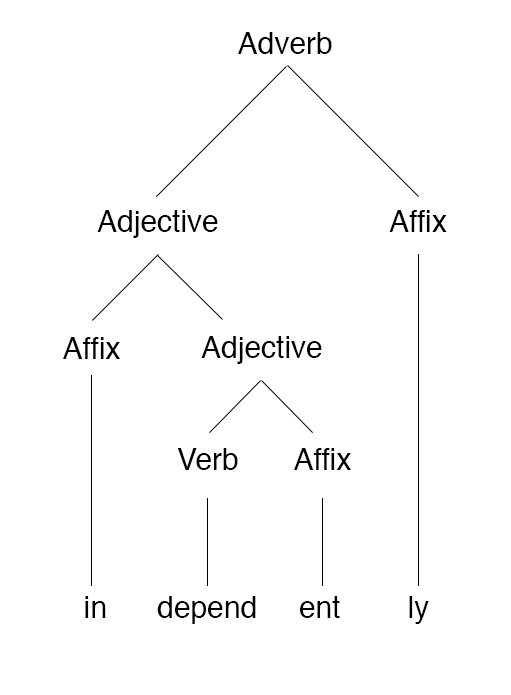

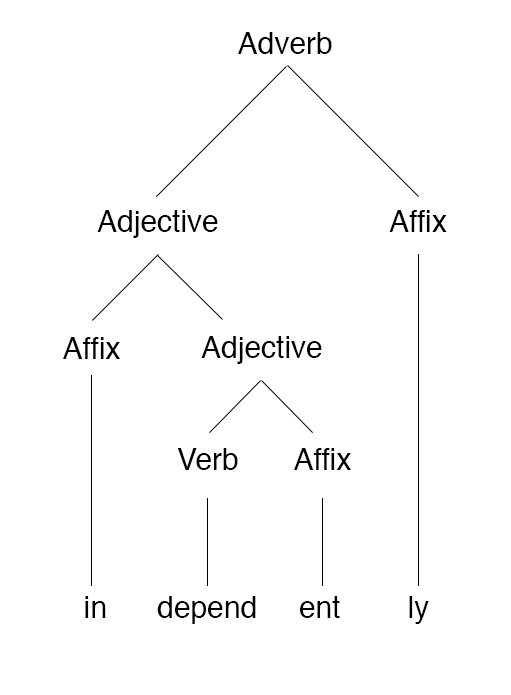

There is a further distinction between two primary kinds of morphological word formation: derivation and compounding. The latter is a process of word formation that involves combining complete word forms into a single compound form. ''Dog catcher'', therefore, is a compound, as both ''dog'' and ''catcher'' are complete word forms in their own right but are subsequently treated as parts of one form. Derivation involves affixing bound (non-independent) forms to existing lexemes, but the addition of the affix derives a new lexeme. The word ''independent'', for example, is derived from the word ''dependent'' by using the prefix ''in-'', and ''dependent'' itself is derived from the verb ''depend''. There is also word formation in the processes of clipping in which a portion of a word is removed to create a new one, blending in which two parts of different words are blended into one, acronyms in which each letter of the new word represents a specific word in the representation (NATO forNorth Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental transnational military alliance of 32 member states—30 European and 2 North American. Established in the aftermat ...

), borrowing in which words from one language are taken and used in another, and coinage in which a new word is created to represent a new object or concept.

Paradigms and morphosyntax

A linguisticparadigm

In science and philosophy, a paradigm ( ) is a distinct set of concepts or thought patterns, including theories, research methods, postulates, and standards for what constitute legitimate contributions to a field. The word ''paradigm'' is Ancient ...

is the complete set of related word forms associated with a given lexeme. The familiar examples of paradigms are the conjugations of verbs and the declensions

In linguistics, declension (verb: ''to wikt:decline#Verb, decline'') is the changing of the form of a word, generally to express its syntactic function in the sentence by way of an inflection. Declension may apply to nouns, pronouns, adjectives, ...

of nouns. Also, arranging the word forms of a lexeme into tables, by classifying them according to shared inflectional categories such as tense, aspect, mood, number

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

, gender

Gender is the range of social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man (or boy), woman (or girl), or third gender. Although gender often corresponds to sex, a transgender person may identify with a gender other tha ...

or case, organizes such. For example, the personal pronouns in English can be organized into tables by using the categories of person

A person (: people or persons, depending on context) is a being who has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations suc ...

(first, second, third); number (singular vs. plural); gender (masculine, feminine, neuter); and case (nominative, oblique, genitive).

The inflectional categories used to group word forms into paradigms cannot be chosen arbitrarily but must be categories that are relevant to stating the syntactic rules of the language. Person and number are categories that can be used to define paradigms in English because the language has grammatical agreement rules, which require the verb in a sentence to appear in an inflectional form that matches the person and number of the subject. Therefore, the syntactic rules of English care about the difference between ''dog'' and ''dogs'' because the choice between both forms determines the form of the verb that is used. However, no syntactic rule shows the difference between ''dog'' and ''dog catcher'', or ''dependent'' and ''independent''. The first two are nouns, and the other two are adjectives.

An important difference between inflection and word formation is that inflected word forms of lexemes are organized into paradigms that are defined by the requirements of syntactic rules, and there are no corresponding syntactic rules for word formation.

The relationship between syntax and morphology, as well as how they interact, is called "morphosyntax";

Dufter and Stark (2017) Introduction – 2 Syntax and morphosyntax: some basic notions

' in Dufter, Andreas, and Stark, Elisabeth (eds., 2017)

Manual of Romance Morphosyntax and Syntax

', Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG the term is also used to underline the fact that syntax and morphology are interrelated.Van Valin, R. D., van Valin Jr, R. D., van Valin Jr, R. D., LaPolla, R. J., & LaPolla, R. J. (1997)

Syntax: Structure, meaning, and function

', p.2, Cambridge University Press. The study of morphosyntax concerns itself with inflection and paradigms, and some approaches to morphosyntax exclude from its domain the phenomena of word formation, compounding, and derivation. Within morphosyntax fall the study of agreement and

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

.

Allomorphy

Above, morphological rules are described as analogies between word forms: ''dog'' is to ''dogs'' as ''cat'' is to ''cats'' and ''dish'' is to ''dishes''. In this case, the analogy applies both to the form of the words and to their meaning. In each pair, the first word means "one of X", and the second "two or more of X", and the difference is always the plural form ''-s'' (or ''-es'') affixed to the second word, which signals the key distinction between singular and plural entities. One of the largest sources of complexity in morphology is that the one-to-one correspondence between meaning and form scarcely applies to every case in the language. In English, there are word form pairs like ''ox/oxen'', ''goose/geese'', and ''sheep/sheep'' whose difference between the singular and the plural is signaled in a way that departs from the regular pattern or is not signaled at all. Even cases regarded as regular, such as ''-s'', are not so simple; the ''-s'' in ''dogs'' is not pronounced the same way as the ''-s'' in ''cats'', and in plurals such as ''dishes'', a vowel is added before the ''-s''. Those cases, in which the same distinction is effected by alternative forms of a "word", constituteallomorph

In linguistics, an allomorph is a variant phonetic form of a morpheme, or in other words, a unit of meaning that varies in sound and spelling without changing the meaning. The term ''allomorph'' describes the realization of phonological variatio ...

y.

Phonological rules constrain the sounds that can appear next to each other in a language, and morphological rules, when applied blindly, would often violate phonological rules by resulting in sound sequences that are prohibited in the language in question. For example, to form the plural of ''dish'' by simply appending an ''-s'' to the end of the word would result in the form , which is not permitted by the phonotactics

Phonotactics (from Ancient Greek 'voice, sound' and 'having to do with arranging') is a branch of phonology that deals with restrictions in a language on the permissible combinations of phonemes. Phonotactics defines permissible syllable struc ...

of English. To "rescue" the word, a vowel sound is inserted between the root and the plural marker, and results. Similar rules apply to the pronunciation of the ''-s'' in ''dogs'' and ''cats'': it depends on the quality (voiced vs. unvoiced) of the final preceding phoneme

A phoneme () is any set of similar Phone (phonetics), speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible Phonetics, phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word fr ...

.

Lexical morphology

Lexical morphology is the branch of morphology that deals with thelexicon

A lexicon (plural: lexicons, rarely lexica) is the vocabulary of a language or branch of knowledge (such as nautical or medical). In linguistics, a lexicon is a language's inventory of lexemes. The word ''lexicon'' derives from Greek word () ...

that, morphologically conceived, is the collection of lexeme

A lexeme () is a unit of lexical meaning that underlies a set of words that are related through inflection. It is a basic abstract unit of meaning, a unit of morphological analysis in linguistics that roughly corresponds to a set of forms ta ...

s in a language. As such, it concerns itself primarily with word formation: derivation and compounding.

Models

There are three principal approaches to morphology and each tries to capture the distinctions above in different ways: * Morpheme-based morphology, which makes use of an item-and-arrangement approach. * Lexeme-based morphology, which normally makes use of an item-and-process approach. * Word-based morphology, which normally makes use of a word-and-paradigm approach. While the associations indicated between the concepts in each item in that list are very strong, they are not absolute.Morpheme-based morphology

In morpheme-based morphology, word forms are analyzed as arrangements of

In morpheme-based morphology, word forms are analyzed as arrangements of morpheme

A morpheme is any of the smallest meaningful constituents within a linguistic expression and particularly within a word. Many words are themselves standalone morphemes, while other words contain multiple morphemes; in linguistic terminology, this ...

s. A morpheme is defined as the minimal meaningful unit of a language. In a word such as ''independently'', the morphemes are said to be ''in-'', ''de-'', ''pend'', ''-ent'', and ''-ly''; ''pend'' is the (bound) root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

and the other morphemes are, in this case, derivational affixes. In words such as ''dogs'', ''dog'' is the root and the ''-s'' is an inflectional morpheme. In its simplest and most naïve form, this way of analyzing word forms, called "item-and-arrangement", treats words as if they were made of morphemes put after each other (" concatenated") like beads on a string. More recent and sophisticated approaches, such as distributed morphology, seek to maintain the idea of the morpheme while accommodating non-concatenated, analogical, and other processes that have proven problematic for item-and-arrangement theories and similar approaches.

Morpheme-based morphology presumes three basic axioms:

* Baudouin's "single morpheme" hypothesis: Roots and affixes have the same status as morphemes.

* Bloomfield's "sign base" morpheme hypothesis: As morphemes, they are dualistic signs, since they have both (phonological) form and meaning.

* Bloomfield's "lexical morpheme" hypothesis: morphemes, affixes and roots alike are stored in the lexicon.

Morpheme-based morphology comes in two flavours, one Bloomfieldian and one Hockettian. For Bloomfield, the morpheme was the minimal form with meaning, but did not have meaning itself. For Hockett, morphemes are "meaning elements", not "form elements". For him, there is a morpheme plural using allomorphs such as ''-s'', ''-en'' and ''-ren''. Within much morpheme-based morphological theory, the two views are mixed in unsystematic ways so a writer may refer to "the morpheme plural" and "the morpheme ''-s''" in the same sentence.

Lexeme-based morphology

Lexeme-based morphology usually takes what is called an item-and-process approach. Instead of analyzing a word form as a set of morphemes arranged in sequence, a word form is said to be the result of applying rules that alter a word-form or stem in order to produce a new one. An inflectional rule takes a stem, changes it as is required by the rule, and outputs a word form; a derivational rule takes a stem, changes it as per its own requirements, and outputs a derived stem; a compounding rule takes word forms, and similarly outputs a compound stem.Word-based morphology

Word-based morphology is (usually) a word-and-paradigm approach. The theory takes paradigms as a central notion. Instead of stating rules to combine morphemes into word forms or to generate word forms from stems, word-based morphology states generalizations that hold between the forms of inflectional paradigms. The major point behind this approach is that many such generalizations are hard to state with either of the other approaches. Word-and-paradigm approaches are also well-suited to capturing purely morphological phenomena, such as morphomes. Examples to show the effectiveness of word-based approaches are usually drawn from fusional languages, where a given "piece" of a word, which a morpheme-based theory would call an inflectional morpheme, corresponds to a combination of grammatical categories, for example, "third-person plural". Morpheme-based theories usually have no problems with this situation since one says that a given morpheme has two categories. Item-and-process theories, on the other hand, often break down in cases like these because they all too often assume that there will be two separate rules here, one for third person, and the other for plural, but the distinction between them turns out to be artificial. The approaches treat these as whole words that are related to each other by analogical rules. Words can be categorized based on the pattern they fit into. This applies both to existing words and to new ones. Application of a pattern different from the one that has been used historically can give rise to a new word, such as ''older'' replacing ''elder'' (where ''older'' follows the normal pattern of adjectival comparatives) and ''cows'' replacing ''kine'' (where ''cows'' fits the regular pattern of plural formation).Morphological typology

In the 19th century, philologists devised a now classic classification of languages according to their morphology. Some languages are isolating, and have little to no morphology; others are agglutinative whose words tend to have many easily separable morphemes (such asTurkic languages

The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic langua ...

); others yet are inflectional or fusional because their inflectional morphemes are "fused" together (like some Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

such as Pashto

Pashto ( , ; , ) is an eastern Iranian language in the Indo-European language family, natively spoken in northwestern Pakistan and southern and eastern Afghanistan. It has official status in Afghanistan and the Pakistani province of Khyb ...

and Russian). That leads to one bound morpheme conveying multiple pieces of information. A standard example of an isolating language is Chinese. An agglutinative language is Turkish (and practically all Turkic languages). Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and Greek are prototypical inflectional or fusional languages.

It is clear that this classification is not at all clearcut, and many languages (Latin and Greek among them) do not neatly fit any one of these types, and some fit in more than one way. A continuum of complex morphology of language may be adopted.

The three models of morphology stem from attempts to analyze languages that more or less match different categories in this typology. The item-and-arrangement approach fits very naturally with agglutinative languages. The item-and-process and word-and-paradigm approaches usually address fusional languages.

As there is very little fusion involved in word formation, classical typology mostly applies to inflectional morphology. Depending on the preferred way of expressing non-inflectional notions, languages may be classified as synthetic (using word formation) or analytic (using syntactic phrases).

Examples

Pingelapese is a Micronesian language spoken on the Pingelap atoll and on two of the eastern Caroline Islands, called the high island of Pohnpei. Similar to other languages, words in Pingelapese can take different forms to add to or even change its meaning. Verbal suffixes are morphemes added at the end of a word to change its form. Prefixes are those that are added at the front. For example, the Pingelapese suffix –''kin'' means 'with' or 'at.' It is added at the end of a verb. :''ius'' = to use → ''ius-kin'' = to use with : = to be good → = to be good at ''sa-'' is an example of a verbal prefix. It is added to the beginning of a word and means 'not.' : = to be correct → = to be incorrect There are also directional suffixes that when added to the root word give the listener a better idea of where the subject is headed. The verb ''alu'' means to walk. A directional suffix can be used to give more detail. :''-da'' = 'up' → ''aluh-da'' = to walk up :''-d''i = 'down' → ''aluh-di'' = to walk down :''-eng'' = 'away from speaker and listener' → ''aluh-eng'' = to walk away Directional suffixes are not limited to motion verbs. When added to non-motion verbs, their meanings are a figurative one. The following table gives some examples of directional suffixes and their possible meanings.See also

* Morphome (linguistics) * Morphological richnessFootnotes

References

Further reading

* * . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Lecture 7 Morphology

in Linguistics 001 by Mark Liberman, ling.upenn.edu

Intro to Linguistics – Morphology

by Jirka Hana, ufal.mff.cuni.cz

by Stephen R. Anderson, part of Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, cowgill.ling.yale.edu

Introduction to Linguistic Theory – Morphology: The Words of Language

by Adam Szczegielniak, scholar.harvard.edu

LIGN120: Introduction to Morphology

by Farrell Ackerman and Henry Beecher, grammar.ucsd.edu

by P. J. Hancox, cs.bham.ac.uk {{Authority control Linguistics terminology Grammar