Wampanoag Tribal Council Of Gay Head, Inc. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Wampanoag, also rendered Wôpanâak, are a

The Wampanoag originally spoke Wôpanâak, a dialect of the

The Wampanoag originally spoke Wôpanâak, a dialect of the

Contacts between the Wampanoag and colonists began in the 16th century when European merchant vessels and fishing boats traveled along the coast of

Contacts between the Wampanoag and colonists began in the 16th century when European merchant vessels and fishing boats traveled along the coast of  After 1632, the Plymouth Colony was outnumbered by the growing Puritans settlements around Boston. The colonists expanded westward into the

After 1632, the Plymouth Colony was outnumbered by the growing Puritans settlements around Boston. The colonists expanded westward into the

Individual towns and regions had differing expectations for Indian conversions. In most of Eliot's mainland praying towns, religious converts were also expected to follow colonial laws and manners and to adopt the material trappings of colonial life. Eliot and other ministers relied on praise and rewards for those who conformed, rather than punishing those who did not. The Christian Indian settlements of

Individual towns and regions had differing expectations for Indian conversions. In most of Eliot's mainland praying towns, religious converts were also expected to follow colonial laws and manners and to adopt the material trappings of colonial life. Eliot and other ministers relied on praise and rewards for those who conformed, rather than punishing those who did not. The Christian Indian settlements of

Massasoit was among those Indians who adopted colonial customs. He asked the legislators in Plymouth near the end of his life to give both of his sons English names. The older son

Massasoit was among those Indians who adopted colonial customs. He asked the legislators in Plymouth near the end of his life to give both of his sons English names. The older son

Native American people

Native Americans (also called American Indians, First Americans, or Indigenous Americans) are the Indigenous peoples of the United States, particularly of the lower 48 states and Alaska. They may also include any Americans whose origins lie ...

of the Northeastern Woodlands currently based in southeastern Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

and formerly parts of eastern Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

.Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. 171. Their historical territory includes the islands of Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the U.S. state of Massachusetts, lying just south of Cape Cod. It is known for being a popular, affluent summer colony, and includes the smaller peninsula Chappaquiddick Isla ...

and Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck Island, Tuckernuck and Muskeget Island, Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and Co ...

.

Today, two Wampanoag tribes are federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes are legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United States.

:

* Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe (formerly Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Tribal Council, Inc.) is one of two federally recognized tribes of Wampanoag people in Massachusetts. Recognized in 2007, they are headquartered in Mashpee, Massachusetts, Mashpee on ...

* Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) (Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project – "Fun with words" https://www.wlrp.org/fun-with-words) is a federally recognized tribe of Wampanoag people based in the town of Aquinnah on the southwest ti ...

.

Herring Pond Tribe is a historical Wampanoag Tribe located in Plymouth and Bourne, Massachusetts

The Wampanoag language

The Massachusett language is an Algonquian language of the Algic language family that was formerly spoken by several peoples of eastern coastal and southeastern Massachusetts. In its revived form, it is spoken in four Wampanoag communities. ...

, also known as Massachusett

The Massachusett are a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for "At the Great Hill," referring to the Blue Hills ...

, is a Southern New England Algonquian

The Eastern Algonquian languages constitute a subgroup of the Algonquian languages. Prior to European contact, Eastern Algonquian consisted of at least 17 languages, whose speakers collectively occupied the Atlantic coast of North America and adj ...

language.

Prior to English contact in the 17th century, the Wampanoag numbered as many as 40,000 people living across 67 villages composing the Wampanoag Nation. These villages covered the territory along the east coast as far as Wessagusset (today called Weymouth), all of what is now Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer months. The ...

and the islands of Natocket and Noepe (now called Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck Island, Tuckernuck and Muskeget Island, Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and Co ...

and Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the U.S. state of Massachusetts, lying just south of Cape Cod. It is known for being a popular, affluent summer colony, and includes the smaller peninsula Chappaquiddick Isla ...

), and southeast as far as Pokanocket (now Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

and Warren

Warren most commonly refers to:

* Warren (burrow), a network dug by rabbits

* Warren (name), a given name and a surname, including lists of persons so named

Warren may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Warren (biogeographic region)

* War ...

, Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

). The Wampanoag lived on this land for over 12,000 years.

From 1615 to 1619, a leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a blood infection caused by the bacterium ''Leptospira'' that can infect humans, dogs, rodents and many other wild and domesticated animals. Signs and symptoms can range from none to mild (headaches, Myalgia, muscle pains, a ...

epidemic carried by rodents arriving in European ships dramatically reduced the population of the Wampanoag and neighboring tribes. Indigenous deaths from the epidemic facilitated the European invasion and colonization of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

. More than 50 years later, Wampanoag Chief Sachem Metacom

Metacomet (c. 1638 in Massachusetts – August 12, 1676), also known as Pometacom, Metacom, and by his adopted English name King Philip,King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1678 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodland ...

(1675–1676) against the colonists. The war resulted in the death of 40 percent of the surviving Wampanoag. The English sold many Wampanoag men into slavery in Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

, the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

, or on plantations and farms run by colonists in New England.

Today, Wampanoag people continue to live in historical homelands and maintain central aspects of their culture while adapting to changing socioeconomic

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

needs. Oral traditions, ceremonies, song and dance, social gatherings, and hunting and fishing remain important traditional ways of life to the Wampanoag. In 2015, the federal government declared 150 acres of land in Mashpee and 170 acres of land in Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England. It is a market town and has a Minster (church), minster church. Its population in 2011 was 64,621. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century priory, monastic foundation, owned by the ...

as the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe (formerly Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Tribal Council, Inc.) is one of two federally recognized tribes of Wampanoag people in Massachusetts. Recognized in 2007, they are headquartered in Mashpee, Massachusetts, Mashpee on ...

’s initial reservation, on which the Tribe can exercise its full tribal sovereignty rights. The Mashpee tribe currently has approximately 3,200 enrolled citizens. The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head

The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) (Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project – "Fun with words" https://www.wlrp.org/fun-with-words) is a federally recognized tribe of Wampanoag people based in the town of Aquinnah on the southwest tip ...

currently has 901 enrolled citizens. Early 21st-century population estimates indicated a total of 4,500 Wampanoag descendants.

Wampanoag activists have been reviving the Wampanoag language; Mashpee High School

Mashpee Middle-High School is a public high school located in Mashpee, Massachusetts, United States. It is located at the intersection of Old Barnstable Road and Route 151, has an approximate enrollment of 700 students in grades 7–12 and is t ...

began a course in 2018 teaching the language.

Name

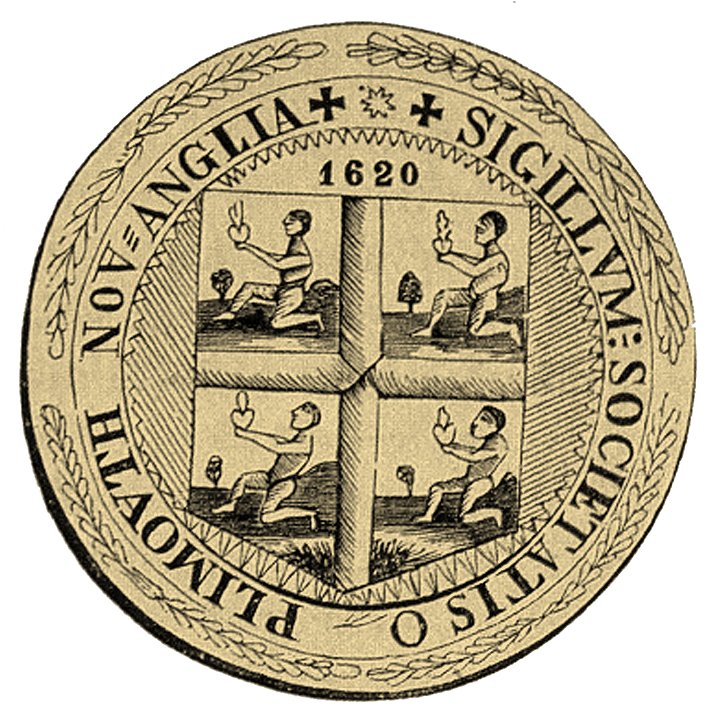

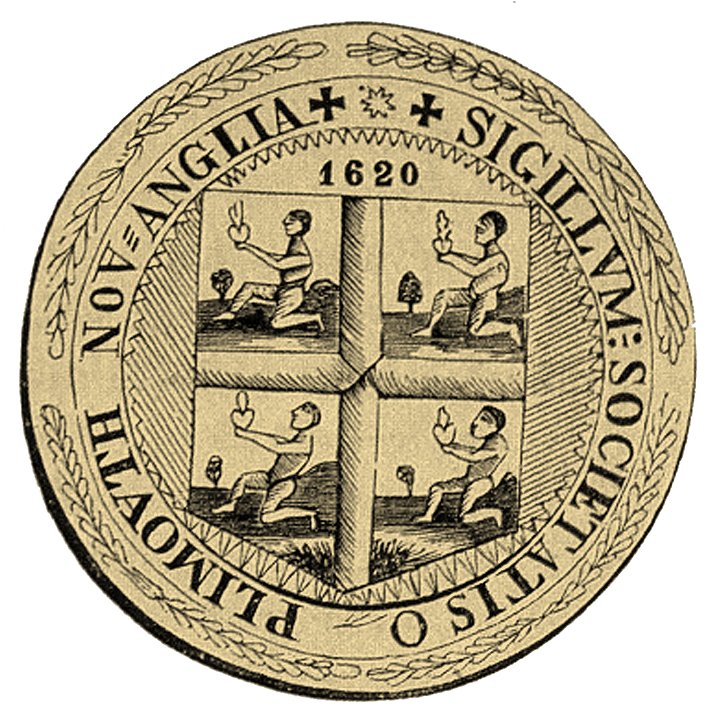

''Wampanoag'' probably derives from ''Wapanoos'', first documented onAdriaen Block

Adriaen Courtsen Block (c. 1567 – 27 April 1627) was a Dutch private trader, privateer, and ship's captain who is best known for exploring the coastal and river valley areas between present-day New Jersey and Massachusetts during four voyages ...

's 1614 map, which was the earliest European representation of the Wampanoag territory. The Wampanoag translate this word to "People of the First Light." Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a History of New England, New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the sixth President of Harvard University, President of Harvard College (la ...

first recorded it in 1676 to describe the alliance of tribes who fought against the English in King Philip's War.

In 1616, John Smith referred to one of the Wampanoag tribes as the Pokanoket

The Pokanoket (also spelled PakanokickKathleen J. Bragdon, ''Native People of Southern New England, 1500–1650'', page 21) are a group of Wampanoag people and the village governed by Massasoit (c. 1581–1661), chief sachem of the Wampanoag pe ...

. The earliest colonial records and reports used ''Pokanoket'' as the name of the tribe whose leaders (the Massasoit Ousemequin until 1661, his son Wamsutta from 1661 to 1662, and Metacomet from 1662 to 1676) led the Wampanoag confederation at the time the English began settling southeastern New England. The Pokanoket were based at Sowams, near where Warren, Rhode Island

Warren is a town in Bristol County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 11,147 at the 2020 census.

History

Warren was the site of the Pokanoket Indian settlement of Sowams located on a peninsula within the Pokanoket region. The reg ...

, developed and on the peninsula where Bristol, Rhode Island, arose after King Philip's War. The Seat of Metacomet, or King Philip's seat, at Mount Hope Bay

Mount Hope Bay is a tidal estuary located at the mouth of the Taunton River on the Massachusetts and Rhode Island border. It is an arm of Narragansett Bay. The bay is named after Mount Hope, a small hill located on its western shore in what is ...

in Bristol, Rhode Island became the political center from which Metacomet began King Philip's War, the first intertribal war of Native American resistance to English settlement in North America.

Wampanoag groups and locations

List

Culture

The Wampanoag people were semi-sedentary (that is, partially nomadic), with seasonal movements between sites in southernNew England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. The men often traveled far north and south along the Eastern seaboard for seasonal fishing expeditions, and sometimes stayed in those distant locations for weeks and months at a time. The women cultivated varieties of the " three sisters" (maize, climbing beans, and squash) as the staples of their diet, supplemented by fish and game caught by the men. Each community had authority over a well-defined territory from which the people derived their livelihood through a seasonal round of fishing, planting, harvesting, and hunting. Southern New England was populated by various tribes, so hunting grounds had strictly defined boundaries.

The Wampanoag had a matrilineal

Matrilineality, at times called matriliny, is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which people identify with their matriline, their mother's lineage, and which can involve the inheritan ...

system, like other Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands include Native American tribes and First Nation bands residing in or originating from a cultural area encompassing the northeastern and Midwest United States and southeastern Canada. It is part ...

, in which women owned property, and hereditary status was passed through the maternal line. They were also matrifocal

A matrifocal family structure is one where mothers head families, and fathers play a less important role in the home and in bringing up children.

Definition

In 1956, the concept of the matrifocal family was introduced to the study of Caribbean ...

; when a young couple married, they lived with the woman's family. Women elders could approve selection of chiefs or sachem

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Alg ...

s. Men acted in most of the political roles for relations with other bands and tribes, as well as warfare. Women passed plots of land to their female descendants, regardless of their marital status.

The production of food among the Wampanoag was similar to that of many American Indian societies, and food habits were divided along gender lines. Men and women had specific tasks. Women played an active role in many of the stages of food production and processing, so they had important socio-political, economic, and spiritual roles in their communities.''Handbook of North American Indians.'' Wampanoag men were mainly responsible for hunting and fishing, while women took care of farming and gathering wild fruits, nuts, berries, and shellfish. Women were responsible for up to 75 percent of all food production in Wampanoag societies.

The Wampanoag were organized into a confederation in which a head sachem

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Alg ...

presided over a number of other sachems. The colonists often referred to him as "king", but the position of a sachem differed in many ways from a king. They were selected by women elders and were bound to consult their own councilors within their tribe, as well as any of the "petty sachems" in the region. They were also responsible for arranging trade privileges, as well as protecting their allies in exchange for material tribute. Both women and men could hold the position of sachem, and women were sometimes chosen over close male relatives.

Pre-marital sexual experimentation was accepted, although the Wampanoag expected fidelity within unions after marriage. Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

(1603–1683) said that "single fornication they count no sin, but after Marriage... they count it heinous for either of them to be false." Polygamy

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

was practiced among the Wampanoag, although monogamy was the norm. Some elite men could take several wives for political or social reasons, and multiple wives were a symbol of wealth. Women were the producers and distributors of corn and other food products. Marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children (if any), and b ...

and conjugal unions were not as important as ties of clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

and kinship.

Language and revival

The Wampanoag originally spoke Wôpanâak, a dialect of the

The Wampanoag originally spoke Wôpanâak, a dialect of the Massachusett language

The Massachusett language is an Algonquian languages, Algonquian language of the Algic languages, Algic language family that was formerly spoken by several peoples of eastern coastal and southeastern Massachusetts. In its revived form, it is s ...

, which belongs to the Algonquian languages

The Algonquian languages ( ; also Algonkian) are a family of Indigenous languages of the Americas and most of the languages in the Algic language family are included in the group. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from ...

family. The first Bible published in America was a 1663 translation into Wampanoag by missionary John Eliot. He created an orthography

An orthography is a set of convention (norm), conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, punctuation, Word#Word boundaries, word boundaries, capitalization, hyphenation, and Emphasis (typography), emphasis.

Most national ...

, which he taught to the Wampanoag. Many became literate, using Wampanoag for letters, deeds, and historic documents.

The rapid decline of Wampanoag speakers began after the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. Neal Salisbury and Colin G. Calloway suggest that New England Indian communities suffered from gender imbalances at this time due to premature male deaths, especially due to warfare and their work in the hazardous trades of whaling and shipping. They posit that many Wampanoag women married outside their linguistic groups, making it difficult for them to maintain the various Wampanoag dialects.

Jessie Little Doe Baird

Jessie Little Doe Baird (also Jessie Little Doe Fermino, born 18 November 1963) is a linguist known for her efforts to revive the Wampanoag (Wôpanâak) language. She is the co-founder of the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project.

She lives i ...

, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, founded the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project

Jessie Little Doe Baird (also Jessie Little Doe Fermino, born 18 November 1963) is a linguist known for her efforts to revive the Wampanoag (Wôpanâak) language. She is the co-founder of the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project.

She lives i ...

in 1993. They have taught some children, who have become the first speakers of Wôpanâak in more than a century. The project is training teachers to reach more children and to develop a curriculum for a ''Wôpanâak''-based school. Baird has developed a 10,000-word Wôpanâak-English dictionary by consulting archival Wôpanâak documents and using linguistic methods to reconstruct

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

unattested words. For this project she was awarded a $500,000.00 grant from the Macarthur Fellows in 2010. She has also produced a grammar, collections of stories, and other books. Mashpee High School

Mashpee Middle-High School is a public high school located in Mashpee, Massachusetts, United States. It is located at the intersection of Old Barnstable Road and Route 151, has an approximate enrollment of 700 students in grades 7–12 and is t ...

began a course in 2018 teaching the language.Sources:

*

*

*

*

History

Contacts between the Wampanoag and colonists began in the 16th century when European merchant vessels and fishing boats traveled along the coast of

Contacts between the Wampanoag and colonists began in the 16th century when European merchant vessels and fishing boats traveled along the coast of New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. In 1524, Giovanni de Verrazano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , ; often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1491–1528) was an Italian (Republic of Florence, Florentine) Exploration, explorer of North America, who led most of his later expeditions, including the one to America, in ...

contacted various tribes such as the Wampanoag and the Narragansett in modern day Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

. Captain Thomas Hunt captured several Wampanoag in 1614 and sold them in Spain as slaves. A Patuxet

The Patuxet were a Native American band of the Wampanoag tribal confederation. They lived primarily in and around modern-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, and were among the first Native Americans encountered by European settlers in the region in the ...

named Tisquantum

Tisquantum (; 1585 (±10 years?) – November 30, 1622 O.S.), more commonly known as Squanto (), was a member of the Patuxet tribe of Wampanoags, best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in Southern New Eng ...

(or Squanto

Tisquantum (; 1585 (±10 years?) – November 30, 1622 Old Style, O.S.), more commonly known as Squanto (), was a member of the Patuxet tribe of Wampanoags, best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in Southe ...

) was kidnapped by Spanish monks who attempted to convert him before setting him free. He accompanied an expedition to Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

as an interpreter, then made his way back to his homeland in 1619, only to

discover that the entire Patuxet tribe had died in an epidemic.''Die Welt der Indianer.''

In 1620, the Pilgrims arrived in Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, and Tisquantum and other Wampanoag taught them how to cultivate the varieties of corn, squash, and beans (the Three Sisters) that flourished in New England, as well as how to catch and process fish and collect seafood. They enabled the Pilgrims to survive their first winters, and Squanto lived with them and acted as a middleman between them and ''Massasoit

Massasoit Sachem ( ) or Ousamequin (1661)"Native People" (page), "Massasoit (Ousamequin) Sachem" (section),''MayflowerFamilies.com'', web pag was the sachem or leader of the Wampanoag confederacy. ''Massasoit'' means ''Great Sachem''. Although ...

'', the Wampanoag sachem

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Alg ...

. In ''Mourt's Relation

The booklet ''Mourt's Relation'' (full title: ''A Relation or Journal of the Beginning and Proceedings of the English Plantation Settled at Plimoth in New England'') was written between November 1620 and November 1621, and describes in detail wha ...

,'' initial contact between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag was recorded as beginning in the Spring of 1621.

The Wampanoag suffered from an epidemic between 1616 and 1619, long thought to be smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

introduced by contact with Europeans. However, a 2010 study suggests that the epidemic was leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a blood infection caused by the bacterium ''Leptospira'' that can infect humans, dogs, rodents and many other wild and domesticated animals. Signs and symptoms can range from none to mild (headaches, Myalgia, muscle pains, a ...

, introduced by rat reservoirs on European ships. The groups most devastated by the illness were those who had traded heavily with the French and the disease was likely a virgin soil epidemic

In epidemiology, a virgin soil epidemic is an epidemic in which populations that previously were in isolation from a pathogen are immunologically unprepared upon contact with the novel pathogen. Virgin soil epidemics have occurred with European ...

. Alfred Crosby

Alfred Worcester Crosby Jr. (January 15, 1931 – March 14, 2018) was a professor of History, Geography, and American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, and University of Helsinki. He was the author of books including '' The Columbian ...

has estimated population losses to be as high as 90 percent among the Massachusett

The Massachusett are a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for "At the Great Hill," referring to the Blue Hills ...

and mainland Pokanoket

The Pokanoket (also spelled PakanokickKathleen J. Bragdon, ''Native People of Southern New England, 1500–1650'', page 21) are a group of Wampanoag people and the village governed by Massasoit (c. 1581–1661), chief sachem of the Wampanoag pe ...

.

Since the late 20th century, the event celebrated as the first Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in October and November in the United States, Canada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Germany. It is also observed in the Australian territory ...

has been debated in the United States. Many American Indians and historians argue against the romanticized story of the Wampanoag celebrating together with the colonists. Some say that there is no documentation of such an event. One primary account of the 1621 event was written by a firsthand observer.

Massasoit became gravely ill in the winter of 1623, but he was nursed back to health by the colonists. In 1632, the Narragansetts

The Narragansett people are an Algonquian American Indian tribe from Rhode Island. Today, Narragansett people are enrolled in the federally recognized Narragansett Indian Tribe. They gained federal recognition in 1983.

The tribe was nearly la ...

attacked Massasoit's village in Sowam, but the colonists helped the Wampanoag to drive them back.

After 1632, the Plymouth Colony was outnumbered by the growing Puritans settlements around Boston. The colonists expanded westward into the

After 1632, the Plymouth Colony was outnumbered by the growing Puritans settlements around Boston. The colonists expanded westward into the Connecticut River Valley

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges into Long Isl ...

. In 1638, they destroyed the powerful Pequot

The Pequot ( ) are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut includin ...

Confederation. In 1643, the Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Indigenous people originally based in what is now southeastern Connecticut in the United States. They are part of the Eastern Algonquian linguistic and cultural family and historically shared close ties with the neighboring ...

s defeated the Narragansetts in a war with support from the colonists, and they became the dominant tribe in southern New England.

Conversion to Christianity

After 1650, John Eliot and other Puritan missionaries sought to convert local tribes to Christianity, and those that converted settled in 14Praying towns

Praying towns were settlements established by British colonization of the Americas, English colonial governments in New England from 1646 to 1675 in an effort to convert local Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans to Christianit ...

. Eliot and his colleagues hoped that the Indians would adopt practices such as monogamous marriage, agriculture, and jurisprudence. The high levels of epidemics among the Indians may have motivated some conversions. Salisbury suggests that the survivors suffered a type of spiritual crisis because their medical and religious leaders had been unable to prevent the epidemic losses.

Individual towns and regions had differing expectations for Indian conversions. In most of Eliot's mainland praying towns, religious converts were also expected to follow colonial laws and manners and to adopt the material trappings of colonial life. Eliot and other ministers relied on praise and rewards for those who conformed, rather than punishing those who did not. The Christian Indian settlements of

Individual towns and regions had differing expectations for Indian conversions. In most of Eliot's mainland praying towns, religious converts were also expected to follow colonial laws and manners and to adopt the material trappings of colonial life. Eliot and other ministers relied on praise and rewards for those who conformed, rather than punishing those who did not. The Christian Indian settlements of Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the U.S. state of Massachusetts, lying just south of Cape Cod. It is known for being a popular, affluent summer colony, and includes the smaller peninsula Chappaquiddick Isla ...

were noted for a great deal of sharing and mixing between Wampanoag and colonial ways of life. Wampanoag converts often continued their traditional practices in dress, hairstyle, and governance. The Martha's Vineyard converts were not required to attend church and they often maintained traditional cultural practices, such as mourning rituals.

The Wampanoag women were more likely to convert to Christianity than the men. Experience Mayhew

Experience Mayhew (1673–1758) was a New England missionary to the Wampanoag Indians on Martha's Vineyard and adjacent islands. He is the author of Massachusett Psalter (a rare book like the Bay Psalm Book and Eliot Indian Bible).

Experience wa ...

said that "it seems to be a Truth with respect to our Indians, so far as my knowledge of them extend, that there have been, and are a greater number of their Women appearing pious than of the men among them" in his text "Indian Converts". The frequency of female conversion created a problem for missionaries, who wanted to establish patriarchal family and societal structures among them. Women had control of property, and inheritance and descent passed through their line, including hereditary leadership for men. Wampanoag women on Martha's Vineyard were the spiritual leaders of their households. In general, English ministers agreed that it was preferable for women to subvert the patriarchal model and assume a dominant spiritual role than it was for their husbands to remain unconverted. Experience Mayhew asked, "How can those Wives answer it unto God who do not Use their utmost Endeavors to Perswade and oblige their husbands to maintain Prayer in their families?" In some cases, Wampanoag women converts accepted changed gender roles under colonial custom, while others practiced their traditional roles of shared power as Christians.

Metacomet (King Philip)

Massasoit was among those Indians who adopted colonial customs. He asked the legislators in Plymouth near the end of his life to give both of his sons English names. The older son

Massasoit was among those Indians who adopted colonial customs. He asked the legislators in Plymouth near the end of his life to give both of his sons English names. The older son Wamsutta

Wamsutta ( 16341662), known to the New England colonists as Alexander, was the eldest son of Massasoit (meaning Great Leader) Ousa Mequin of the Pokanoket within the Wampanoag nation, and the brother of Metacomet (or Metacom).

Life

Wamsutta was ...

was given the name Alexander, and his younger brother Metacom

Metacomet (c. 1638 in Massachusetts – August 12, 1676), also known as Pometacom, Metacom, and by his adopted English name King Philip,Wampanoag History

/ref> Under Philip's leadership, the relationship changed dramatically between the Wampanoag and the colonists. Philip believed that the ever-increasing colonists would eventually take over everything — not only land, but also their culture, their way of life, and their religion — so he decided to limit the further expansion of colonial settlements. The Wampanoag numbered only 1,000, and Philip began to visit other tribes to build alliances among those who also wanted to push out the colonists. At that time, the population colonists in southern New England was already more than double that of the Indians, at 35,000 to 15,000. In 1671, Philip was called to

An Indian Deed relating to the Petition of Reuben Cognehew

presented a provision established by a representative of the community named Quatchatisset establishing that the allotment would " for ever not to be sold or given or alienated from them is descendantsor any part of these lands." Property deeds in 1671 recorded this area known as the Mashpee Plantation as consisting of around 55 square miles of land. The area was integrated into the district of Mashpee in 1763. In 1788 after the

Today, there are two

Today, there are two

The

The

"Moby-Dick"

chapter 27. ''The

''Colonial Intimacies: Indian Marriage in Early New England''.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000. * * Salisbury, Neal. ''Manitou and Providence''. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1982. * Leach, Douglas Edward. ''Flintlock and Tomahawk''. New York: W. W. Norton. , 1958. * Ronda, James P. "Generations of Faith: The Christian Indians of Martha's Vineyard." ''William and Mary Quarterly'' 38, 1981. . . * Salisbury, Neal. ''Introduction to The Sovereignty and Goodness of God by Mary Rowlandson''. Boston: Bedford Books, 1997. * Salisbury, Neal. ''Manitou and Providence''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982. * Salisbury, Neal, and Colin G. Calloway, eds. ''Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience''. Vol. 71 of Publications of the

Indian Converts Collection

* Silverman, David. ''Faith and Boundaries: Colonists, Christianity, and Community Among the Wampanoag Indians of Martha's Vineyard, 1600–1871''. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. . * Waters, Kate, and Kendall, Russ. ''Tapenum's Day: A Wampanoag Indian Boy in Pilgrim Times''. New York: Scholastic, 1996. .

INDIGENOUS LAND OWNERSHIP IN 17TH CENTURY MISSION COMMUNITIES: A SURVIVAL STORY FROM SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND

A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Taylor J. Kirsch

The History of Martha's Vineyard, Dukes County, Massachusetts, in three volumes, Volume I.

Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project

Plimoth Plantation

living history

Listening to Wampanoag Voices: Beyond 1620

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology {{DEFAULTSORT:Wampanoag Algonquian ethnonyms Algonquian peoples Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands King Philip's War Martha's Vineyard Nantucket, Massachusetts Native American history of Massachusetts Native American history of Rhode Island Native American tribes in Massachusetts Native American tribes in Rhode Island Plymouth Colony

/ref> Under Philip's leadership, the relationship changed dramatically between the Wampanoag and the colonists. Philip believed that the ever-increasing colonists would eventually take over everything — not only land, but also their culture, their way of life, and their religion — so he decided to limit the further expansion of colonial settlements. The Wampanoag numbered only 1,000, and Philip began to visit other tribes to build alliances among those who also wanted to push out the colonists. At that time, the population colonists in southern New England was already more than double that of the Indians, at 35,000 to 15,000. In 1671, Philip was called to

Taunton, Massachusetts

Taunton is a city in and the county seat of Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. Taunton is situated on the Taunton River, which winds its way through the city on its way to Mount Hope Bay, to the south. As of the 2020 United States ...

, where he listened to the accusations of the colonists and signed an agreement that required the Wampanoag to give up their firearms. To be on the safe side, he did not take part in the subsequent dinner. His men never delivered their weapons.

Philip gradually gained the Nipmuck

The Nipmuc or Nipmuck people are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who historically spoke an Eastern Algonquian language, probably the Loup language. Their historic territory Nippenet, meaning 'the freshwater pond place', is i ...

, Pocomtuc

The Pocomtuc (also Pocomtuck, Pocumtuc, Pocumtuck, or Deerfield Indians) were a Native American tribe historically inhabiting western areas of Massachusetts.

Settlements

Their territory was concentrated around the confluence of the Deerfield ...

, and Narragansett as allies, and the beginning of the uprising was first planned for the spring of 1676. In March 1675, however, John Sassamon

John Sassamon, also known as Wussausmon (), was a Massachusett man who lived in New England during the colonial era. He converted to Christianity and became a praying Indian, helping to serve as an interpreter to New England colonists. In Janu ...

was murdered. Sassamon was a Christian Indian raised in Natick, one of the praying towns. He was educated at Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate education, undergraduate college of Harvard University, a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Part of the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Scienc ...

and had served as a scribe, interpreter, and counselor to Philip and the Wampanoag. But, a week before his death, Sassamon reported to Plymouth governor Josiah Winslow

Josiah Winslow ( in Plymouth Colony – 1680 in Marshfield, Plymouth Colony) was the 13th Governor of Plymouth Colony. In records of the time, historians also name him Josias Winslow, and modern writers have carried that name forward. He was b ...

that Philip was planning a war against the colonists.

Sassamon was found dead under the ice of Assawompsett Pond a week later. A Christian Indian accused three Wampanoag warriors of his murder. The colonists took the three captive and hanged them in June 1675 after a trial by a jury of 12 colonists and six Christian Indians. This execution, combined with rumors that the colonists wanted to capture Philip, was a catalyst for war. Philip called a council of war on Mount Hope. Most Wampanoag wanted to follow him, except the Nauset

The Nauset people, sometimes referred to as the Cape Cod Indians, were a Native American tribe who lived in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. They lived east of Bass River and lands occupied by their closely related neighbors, the Wampanoag.

Although th ...

on Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer months. The ...

and the small groups on the offshore islands. Allies included the Nipmuc, Pocomtuc, some Pennacook

The Pennacook, also known by the names Penacook and Pennacock, were Algonquian Indigenous people who lived in what is now Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and southern Maine. They were not a united tribe but a network of politically and culturally ...

, and eastern Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pred ...

from farther north. The Narragansett remained neutral at the beginning of the war.

King Philip's War

On June 20, 1675, some Wampanoag attacked colonists inSwansea, Massachusetts

Swansea is a town in Bristol County in southeastern Massachusetts, United States.

It is located at the mouth of the Taunton River, just west of Fall River, south of Boston, and southeast of Providence, Rhode Island. The population was 17,14 ...

, and laid siege to the town. Five days later, they destroyed it completely, leading to King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1678 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodland ...

. The united tribes in southern New England attacked 52 of 90 colonial settlements and partially burned them down.

At the outbreak of the war, many Indians offered to fight with the colonists against King Philip and his allies, serving as warriors, scouts, advisers, and spies. Mistrust and hostility eventually caused the colonists to discontinue Indian assistance, even though they were invaluable in the war. The Massachusetts government moved many Christian Indians to Deer Island in Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, located adjacent to Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the Northeastern United States.

History 17th century

Since its dis ...

, in part to protect the "

praying Indians" from vigilantes, but also as a precautionary measure to prevent rebellion and sedition from them. Mary Rowlandson

Mary Rowlandson, née White, later Mary Talcott (c. 1637January 5, 1711), was a colonial American woman who was captured by Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans in 1676 during King Philip's War and held for 11 weeks before being ...

's ''The Sovereignty and Goodness of God'' is an account of her months of captivity by the Wampanoag during King Philip's War in which she expressed shock at the cruelties from Christian Indians.

From Massachusetts, the war spread to other parts of New England. The Kennebec, Pigwacket (Pequawket

The Pequawket were a Native American band of Abenaki people. In the 18th century, they lived in New Hampshire and Maine.

Territory

The Pequawket lived near the headwaters of the Saco River and near what is now Carroll County, New Hampshire a ...

s), and Arosaguntacook from Maine joined in the war against the colonists. The Narragansetts of Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

gave up their neutrality after the colonists attacked one of their fortified villages. The Narragansetts lost more than 600 people and 20 sachems in the battle which became known as the "Great Swamp Massacre

The Great Swamp Massacre or the Great Swamp Fight was a crucial battle fought during King Philip's War between the colonial militia of New England and the Narragansett people in December 1675. It was fought near the villages of Kingston and We ...

". Their leader Canonchet was able to flee and led a large group of Narragansett warriors west to join King Philip's warriors.

The war turned against Philip in the spring of 1676, following a winter of hunger and deprivation. The colonial troops set out after Canonchet and took him captive. After a firing squad executed him, colonists quartered his corpse and sent his head to Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. The city, located in Hartford County, Connecticut, Hartford County, had a population of 121,054 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ce ...

, where it was set on public display.

During the summer months, Philip escaped from his pursuers and went to a hideout on Mount Hope in Rhode Island. Colonial forces attacked in August, killing and capturing 173 Wampanoags. Philip barely escaped capture, but his wife and their nine-year-old son were captured and put on a ship at Plymouth. They were then sold as slaves in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

. On August 12, 1676, colonial troops surrounded Philip's camp, and soon shot and killed him.

Consequences of the war

With the death of Metacomet and most of their leaders, the Wampanoags were nearly exterminated; only about 400 survived the war. The Narragansetts andNipmuck

The Nipmuc or Nipmuck people are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who historically spoke an Eastern Algonquian language, probably the Loup language. Their historic territory Nippenet, meaning 'the freshwater pond place', is i ...

s suffered similar rates of losses, and many small tribes in southern New England were finished. In addition, many Wampanoag were sold into slavery. Male captives were generally sold to slave traders and transported to the West Indies, Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, or the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

. The colonists used the women and children as slaves or indentured servants in New England, depending on the colony. Massachusetts resettled the remaining Wampanoags in Natick

Natick ( ) is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is near the center of the MetroWest region of Massachusetts, with a population of 37,006 at the 2020 census. west of Boston, Natick is part of the Greater Boston area. ...

, Wamesit, Punkapoag, and Hassanamesit, four of the original 14 praying towns. These were the only ones to be resettled after the war. Overall, approximately 5,000 Indians (40 percent of their population) and 2,500 colonists (5 percent) were killed in King Philip's War.

18th to 20th century

Mashpee

The exception to relocation was the coastal islands' Wampanoag groups, who had stayed neutral through the war. The colonists forced the Wampanoag of the mainland to resettle with the Saconnet (Sekonnet), or with theNauset

The Nauset people, sometimes referred to as the Cape Cod Indians, were a Native American tribe who lived in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. They lived east of Bass River and lands occupied by their closely related neighbors, the Wampanoag.

Although th ...

into the praying towns in Barnstable County. Mashpee is the largest Indian reservation

An American Indian reservation is an area of land land tenure, held and governed by a List of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States#Description, U.S. federal government-recognized Native American tribal nation, whose gov ...

set aside in Massachusetts, and is located on Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer months. The ...

. In 1660, the colonists allotted the natives about there, and beginning in 1665 they had self-government, adopting an English-style court of law and trials. Mashpee sachems Wepquish and Tookenchosin declared in 1665 that this land would not be able to be sold to non-Mashpee without the unanimous consent of the tribe, writing "We freely give these lands forementioned unto the South Sea Indians and their children forever: and not to be sold or given away from them by anyone without all their consents thereunto.An Indian Deed relating to the Petition of Reuben Cognehew

presented a provision established by a representative of the community named Quatchatisset establishing that the allotment would " for ever not to be sold or given or alienated from them is descendantsor any part of these lands." Property deeds in 1671 recorded this area known as the Mashpee Plantation as consisting of around 55 square miles of land. The area was integrated into the district of Mashpee in 1763. In 1788 after the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, the state revoked the Wampanoag ability to self-govern, considering it a failure. It appointed a supervisory committee consisting of five European-American members, with no Wampanoag. In 1834, the state returned a certain degree of self-government to the First Nations People, and although the First Nations People were far from autonomous, they continued in this manner. To support assimilation, in 1842 the state violated the Nonintercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act (also known as the Indian Intercourse Act or the Indian Nonintercourse Act) is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the United States Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set boundaries of ...

when it illegally allocated plots from of their communal , to be distributed in parcels to each household for subsistence farming, although New England communities were adopting other types of economies. The state passed laws to try to control white encroachment on the reservation; some stole wood from its forests. A large region, once rich in wood, fish, and game, it was considered highly desirable by the whites. With competition between whites and the Wampanoag, conflicts were more frequent than for more isolated native settlements elsewhere in the state. In 1870, each member of the Mashpee tribe over the age of 18 was granted 60 acres of land for private ownership, effectively dismantling the thousands of acres of common tribal lands, and by 1871, non-Mashpee land ownership of the choicest portions of land purchased from impoverished Mashpee, leading to significant loss of Mashpee land ownership.

Wampanoag on Martha's Vineyard

On Martha's Vineyard in the 18th and 19th centuries, there were three reservations— Chappaquiddick, Christiantown andGay Head

Aquinnah ( ; ) is a town located on the western end of Martha's Vineyard island, Massachusetts, United States. From 1870 to 1997, the town was incorporated as Gay Head. At the 2020 U.S. census, the population was 439. Aquinnah is known for its b ...

. The Chappaquiddick Reservation was part of a small island of the same name and was located on the eastern point of that island. As the result of the sale of land in 1789, the natives lost valuable areas, and the remaining land was distributed among the Indian residents in 1810. In 1823 the laws were changed, in order to hinder those trying to get rid of the natives and to implement a visible beginning of a civic organization. Around 1849, they owned of infertile land, and many of the residents moved to nearby Edgartown

Edgartown is a town on the island of Martha's Vineyard in Dukes County, Massachusetts, United States, for which it is the county seat. The town's population was 5,168 at the 2020 census.

It was once a major whaling port, with historic houses ...

, so that they could practice a trade and obtain some civil rights.''Handbook of North American Indians.'' Chapter: Indians of Southern New England and Long Island, late period, pp. 178.

Christiantown was originally a praying town on the northwest side of Martha's Vineyard, northwest of Tisbury. In 1849 the reservation still consisted of , of which all but 10 were distributed among the residents. The land, kept under community ownership, yielded very few crops and the tribe members left it to get paying jobs in the cities. Wampanoag oral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information from

people, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people who pa ...

tells that Christiantown was wiped out in 1888 by a smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

epidemic.

The third reservation on Martha's Vineyard was constructed in 1711 by the New England Company

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England (also known as the New England Company or Company for Propagation of the Gospel in New England and the parts adjacent in America) is a British charitable organization created to promote ...

(founded in 1649) to Christianize the natives. They bought land for the Gay Head natives who had lived there since before 1642. There was considerable dispute about how the land should be cultivated, as the colony had leased the better sections to the whites at low interest. The original goal of creating an undisturbed center for missionary work was quickly forgotten. The state finally created a reservation on a peninsula on the western point of Martha's Vineyard and named it Gay Head. This region was connected to the main island by an isthmus; it enabled the isolation desired by the Wampanoag. In 1849 they had there, of which 500 acres were distributed among the tribe members. The rest was communal property. In contrast to the other reservation groups, the tribe had no guardian or headman. When they needed advice on legal questions, they asked the guardian of the Chappaquiddick Reservation, but other matters they handled themselves. The band used usufruct

Usufruct () is a limited real right (or ''in rem'' right) found in civil law and mixed jurisdictions that unites the two property interests of ''usus'' and ''fructus'':

* ''Usus'' (''use'', as in usage of or access to) is the right to use or en ...

title, meaning that members had no legal claim to their land and allowed the tribal members free rein over their choice of land, as well as over cultivation and building, in order to make their ownership clear. They did not allow whites to settle on their land. They made strict laws regulating membership in the tribe. As a result, they were able to strengthen the groups' ties to each other, and they did not lose their tribal identity until long after other groups had lost theirs.

The Wampanoag on Nantucket Island

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined cou ...

were almost completely destroyed by an unknown plague in 1763; the last Nantucket Wampanoag died in 1855.

Sachems of the Wampanoag

Current status

Today, there are two

Today, there are two federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes are legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United States.

Wampanoag tribes and one state-recognized

State-recognized tribes in the United States are Native American tribes or heritage groups that do not meet the criteria for federally recognized Indian tribes but have been recognized by state government through laws, governor's executive orders ...

Wampanoag tribe. The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe (formerly Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Tribal Council, Inc.) is one of two federally recognized tribes of Wampanoag people in Massachusetts. Recognized in 2007, they are headquartered in Mashpee, Massachusetts, Mashpee on ...

has about 3,200 enrolled citizens in 2023. The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) (Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project – "Fun with words" https://www.wlrp.org/fun-with-words) is a federally recognized tribe of Wampanoag people based in the town of Aquinnah on the southwest ti ...

had 1,364 enrolled tribal citizens in 2019. The state-recognized Herring Pond Tribe has not posted their citizen records.

Some genealogy experts testified that some of the tribes did not demonstrate the required continuity since historic times. For instance, in his testimony to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the historian Francis Hutchins said that the Mashpee "were not an Indian tribe in the years 1666, 1680, 1763, 1790, 1834, 1870, and 1970, or at any time between 1666 and 1970."Day 36, 130–140. In his opinion, an Indian tribe was "an entity composed of persons of American Indian descent, which entity possesses distinct political, legal, cultural attributes, which attributes have descended directly from aboriginal precursors." Without accounting for cultural change, adaptation, and the effects of non-Indian society, Hutchins argued the Mashpee were not an Indian tribe historically because they adopted Christianity and non-Indian forms of dress and appearance, and chose to remain in Massachusetts as "second-class" citizens rather than emigrating westward (note: to Indian Territory) to "resume tribal existence." Hutchins also noted that they intermarried with non-Indians to create a "non-white" or "colored" community. Hutchins appeared to require unchanged culture, including maintenance of a traditional religion and essentially total social autonomy from non-Indian society."

A project titled "Massachusetts Native Peoples and the Social Contract: A Reassessment for Our Times" began in 2015 to serve as an updated report on the cultural, linguistic, and economic state of Wampanoag peoples, including those from federally and non-federally recognized tribes.

Federally recognized Wampanoag tribes

Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

TheMashpee Wampanoag Tribe

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe (formerly Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Tribal Council, Inc.) is one of two federally recognized tribes of Wampanoag people in Massachusetts. Recognized in 2007, they are headquartered in Mashpee, Massachusetts, Mashpee on ...

consists of more than 1,400 enrolled members who must meet defined membership requirements including lineage, community involvement and reside within 20 miles of Mashpee. Since 1924 they have held an annual powwow

A powwow (also pow wow or pow-wow) is a gathering with dances held by many Native Americans in the United States, Native American and First Nations in Canada, First Nations communities. Inaugurated in 1923, powwows today are an opportunity fo ...

at the beginning of July in Mashpee. This first powwow was held at the New Light Baptist Church, at the time called Pondville Church, in Pondville, Massachusetts. The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Council was established in 1972 under the leadership of its first president, Russell "Fast Turtle" Peters. In 1974 the Council petitioned the Bureau of Indian Affairs for recognition. In 1976 the tribe sued the Town of Mashpee for the return of ancestral homelands. The case was lost but the tribe continued to pursue federal recognition for three decades.

In 2000 the Mashpee Wampanoag council was headed by chairman Glenn Marshall. Marshall led the group until 2007 when it was disclosed that he had a prior conviction for rape, had lied about having a military record and was under investigation associated for improprieties associated with the tribe's casino lobbying efforts. Marshall was succeeded by tribal council vice- chair Shawn Hendricks. He held the position until Marshall pleaded guilty in 2009 to federal charges of embezzling, wire fraud, mail fraud, tax evasion and election finance law violations. He steered tens of thousands of dollars in illegal campaign contributions to politicians through the tribe's hired lobbyist Jack Abramoff

Jack Allan Abramoff (; born February 28, 1959) is an American lobbyist, businessman, film producer, writer, and convicted criminal. He was at the center of an extensive federal corruption investigation, which resulted in his conviction and 21 ...

, who was convicted of numerous charges in a much larger scheme. Following the arrests of Abramoff and Marshall, the newly recognized Mashpee Tribe led by new chair Shawn Hendricks, continued to work with Abramoff lobbyist colleague Kevin A. Ring

Kevin A. Ring (born October 19, 1970) is a former American attorney and congressional staffer; he served Republicans in both the House and the Senate, including U.S. Representative John T. Doolittle (R-CA). He also served as a counsel on the Sena ...

pursuing their Indian gaming-related interests. Ring was subsequently convicted on corruption charges linked to his work for the Mashpee band. Tribal elders who had sought access to the tribal council records detailing the council's involvement in this scandal via a complaint filed in Barnstable Municipal Court were shunned by the council and banned them from the tribe for seven years.

In 2009 the tribe elected council member Cedric Cromwell to the position of council chair and president. Cromwell ran a campaign based on reforms and distancing himself from the previous chairmen, even though he had served as a councilor for the prior six years during which the Marshall and Abramoff scandals took place – including voting for the shunning of tribe members who tried to investigate. A challenge to Cromwell's election by defeated candidates following allegations of tampering with voting and enrollment records was filed with the Tribal Court, and Cromwell's administration has been hampered by a series of protest by Elders over casino-related finances.

The Mashpee Wampanoag tribal offices are located in Mashpee on Cape Cod. After decades of legal disputes, the Mashpee Wampanoag obtained provisional recognition as an Indian tribe from the Bureau of Indian Affairs in April 2006, and official Federal recognition in February 2007.

Tribal members own some land, as well as land held in common by Wampanoag descendants at both Chapaquddick and Christiantown. Descendants have also purchased land in Middleborough, Massachusetts

Middleborough is a town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 24,405 as of 2023. The census-designated place of Middleborough Center, Massachusetts, Middleborough Center corresponds to the main village and commercia ...

, upon which the tribe under Glenn A. Marshall's leadership had lobbied to build a casino

A casino is a facility for gambling. Casinos are often built near or combined with hotels, resorts, restaurants, retail shops, cruise ships, and other tourist attractions. Some casinos also host live entertainment, such as stand-up comedy, conce ...

. The tribe has moved its plans to Taunton, Massachusetts

Taunton is a city in and the county seat of Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. Taunton is situated on the Taunton River, which winds its way through the city on its way to Mount Hope Bay, to the south. As of the 2020 United States ...

, but their territorial rights have been challenged by the Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe of the Pokanoket Nation

The Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe of the Pokanoket Nation is one of several cultural heritage organizations of individuals who identify as descendants of the Wampanoag people in Rhode Island. They formed a nonprofit organization, the Pocasset Pokanok ...

, an organization not recognized as a tribe.

But Indian gaming operations are regulated by the National Indian Gaming Commission

The National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC; ) is a United States federal regulatory agency within the Department of the Interior. Congress established the agency pursuant to the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988.

The commission is the only ...

established by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (, ''et seq.'') is a 1988 United States federal law that establishes the jurisdictional framework that governs Indian gaming. There was no federal gaming structure before this act. The stated purposes of the ...

. It contains a general prohibition against gaming on lands acquired into trust after October 17, 1988. The tribe's attempts to gain approvals have been met with legal and government approval challenges.

The Wampanoag Tribe's plan as of 2011 had agreement for financing by the Malaysian Genting Group

The Genting Group is headquartered in Wisma Genting in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The Group comprises the holding company Genting Berhad (), its listed subsidiaries Genting Malaysia Berhad (), Genting Plantations Berhad (), Genting Singapore Plc () ...

and has the political support of Massachusetts Senator John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician, and diplomat who served as the 68th United States secretary of state from 2013 to 2017 in the Presidency of Barack Obama#Administration, administration of Barac ...

, Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick

Deval Laurdine Patrick (born July 31, 1956) is an American politician who served as the 71st governor of Massachusetts from 2007 to 2015. He was the first African Americans, African-American Governor of Massachusetts and the first Democratic Pa ...

, and former Massachusetts Congressman Bill Delahunt

William David Delahunt (; July 18, 1941March 30, 2024) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in the U.S. House of Representatives representing from 1997 to 2011. Delahunt did not ...

, who is working as a lobbyist to represent the casino project. Both Kerry and Delahunt received campaign contributions from the Wampanoag Tribe in transactions authorized by Glenn Marshall as part of the Abramoff lobbying scandal.

In November 2011, the Massachusetts legislature passed a law to license up to three sites for gaming resort casinos and one for a slot machine parlor. The Wampanoag are given a "headstart" to develop plans for a casino in southeastern part of the state.

A December 2021 ruling from the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation ...

gives the Mashpee Wampanoag "substantial control" over 320 acres on Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer months. The ...

. The Obama administration

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. Obama, a Democrat from Illinois, took office following his victory over Republican nomine ...

had put the land in federal trust, but the Trump administration Presidency of Donald Trump may refer to:

* First presidency of Donald Trump, the United States presidential administration from 2017 to 2021

* Second presidency of Donald Trump, the United States presidential administration since 2025

See also

* ...

reversed that decision. A federal judge blocked that action and the federal government appealed, but the Biden administration

Joe Biden's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 46th president of the United States began with Inauguration of Joe Biden, his inauguration on January 20, 2021, and ended on January 20, 2025. Biden, a member of the Democr ...

dropped the appeal.

Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

The

The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) (Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project – "Fun with words" https://www.wlrp.org/fun-with-words) is a federally recognized tribe of Wampanoag people based in the town of Aquinnah on the southwest ti ...

are headquartered in Aquinnah, Massachusetts

Aquinnah ( ; ) is a town located on the western end of Martha's Vineyard island, Massachusetts, United States. From 1870 to 1997, the town was incorporated as Gay Head. At the 2020 U.S. census, the population was 439. Aquinnah is known for its b ...

. ''Aquinnah'' translates as "land under the hill". They are the only Wampanoag tribe to have a formal land-in-trust reservation, which is located on Martha's Vineyard. Their reservation consists of and is located on the outermost southwest part of the island. In 1972, Aquinnah Wampanoag descendants formed the Wampanoag Tribal Council of Gay Head, Inc., to achieve self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

and federal recognition. The Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States List of United States federal agencies, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

recognized the tribe in 1987. The tribe has 1,121 enrolled citizens.

Gladys Widdiss

Gladys A. Widdiss (October 26, 1914 – June 13, 2012) was an American tribal elder, Wampanoag historian and potter. Widdis served as the President of the Aquinnah Wampanoag of Gay Head from 1978 until 1987. She then served as the vice chairman of ...

, an Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal historian and potter, served as the President of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head from 1978 to 1987. The Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head won federal recognition from the United States government during her tenure. Under Widdis, the Aquinnah Wampanoag also acquired the Herring Creek, the Gay Head Cliffs

Aquinnah ( ; ) is a New England town, town located on the western end of Martha's Vineyard island, Massachusetts, United States. From 1870 to 1997, the town was incorporated as Gay Head. At the 2020 U.S. census, the population was 439. Aquinnah ...

, and the cranberry bogs surrounding Gay Head (now called Aquinnah) during her presidency.

The Aquinnah Wampanoag are led by tribal council chair Cheryl Andrews-Maltais, who was elected to the post in November 2007. In 2010, Andrews-Maltais put forward plans for the development of an Aquinnah reservation casino, which was met with opposition by state and local officials.

State-recognized tribe

TheHerring Pond Wampanoag Tribe

The Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe is a state-recognized tribe and nonprofit organization in Massachusetts. The members of the tribe are descendants of Wampanoag people. They are based in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Their nonprofit organization is nam ...

is a state-recognized tribe based in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey

Maura Tracy Healey (born February 8, 1971) is an American lawyer and politician serving as the 73rd governor of Massachusetts since 2023. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, she served as Massachusetts Attorney Ge ...

granted them state-recognition on November 19, 2024 through Executive Order 637.

Cultural heritage groups

Numerousorganizations that self-identify as Native American tribes

These organizations, located within the United States, self-identify as Native American tribes, heritage groups, or descendant communities, but they are not federally recognized or state-recognized as Native American tribes. The U.S. Governmental ...

identify as Wampanoag. The Massachusetts' Commission on Indian Affairs works with some of these organizations.

Some groups have submitted letters of intent to petition for federal acknowledgment, but none have actively petitioned for federal acknowledgment. Unrecognized groups who identify as being of Wampanoag descent include:

# Assawompsett-Nemasket Band of Wampanoags

# Assonet Band of Wampanoags

# Chappaquiddick Wampanoag Tribe, South Yarmouth, MA (Letter of Intent to Petition 05/21/2007)

# Massachuset-Ponkapoag Tribal Council, Holliston, MA

# Nova Scotia Wampanoag Council, Clark's Harbour, NS

# Pocasset Wampanoag Indian Tribe, Great Falls, MA. (Letter of Intent to Petition 1/23/1995)

# Seaconke Wampanoag Tribe

The Seaconke Wampanoag Tribe is one of several cultural heritage organizations of individuals who identify as descendants of the Wampanoag people in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. Multiple nonprofit organizations were formed to represent the Seac ...