Vasil Levski on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vasil Levski ( bg, Васил Левски, spelled in old Bulgarian orthography as , ), born Vasil Ivanov Kunchev (; 18 July 1837 – 18 February 1873), was a Bulgarian revolutionary who is, today, a national hero of

Fellow revolutionary Panayot Hitov later described the adult Levski as being of medium height and having an agile, wiry appearance—with light, greyish-blue eyes, blond hair, and a small moustache. He added that Levski abstained from smoking and drinking. Hitov's memories of Levski's appearance are supported by Levski's contemporaries, revolutionary and writer Lyuben Karavelov and teacher Ivan Furnadzhiev. The only differences are that Karavelov claimed Levski was tall rather than of medium height, while Furnadzhiev noted that his moustache was light brown and his eyes appeared hazel.

Levski began his education at a school in Karlovo, studying homespun tailoring as a local craftsman's apprentice. In 1855, Levski's uncle Basil—archimandrite and envoy of the Hilandar monastery—took him to

Fellow revolutionary Panayot Hitov later described the adult Levski as being of medium height and having an agile, wiry appearance—with light, greyish-blue eyes, blond hair, and a small moustache. He added that Levski abstained from smoking and drinking. Hitov's memories of Levski's appearance are supported by Levski's contemporaries, revolutionary and writer Lyuben Karavelov and teacher Ivan Furnadzhiev. The only differences are that Karavelov claimed Levski was tall rather than of medium height, while Furnadzhiev noted that his moustache was light brown and his eyes appeared hazel.

Levski began his education at a school in Karlovo, studying homespun tailoring as a local craftsman's apprentice. In 1855, Levski's uncle Basil—archimandrite and envoy of the Hilandar monastery—took him to

In the spring of 1863, Levski returned to Bulgarian lands after a brief stay in

In the spring of 1863, Levski returned to Bulgarian lands after a brief stay in

In Serbia, the government was again favourable towards the Bulgarian revolutionaries' aspirations and allowed them to establish in Belgrade the Second Bulgarian Legion, an organisation similar to its predecessor and its goals. Levski was a prominent member of the Legion, but between February and April 1868 he suffered from a gastric condition that required surgery. Bedridden, he could not participate in the Legion's training. After the Legion was again disbanded under political pressure, Levski attempted to reunite with his compatriots, but was arrested in Zaječar and briefly imprisoned. Upon his release he went to Romania, where

In Serbia, the government was again favourable towards the Bulgarian revolutionaries' aspirations and allowed them to establish in Belgrade the Second Bulgarian Legion, an organisation similar to its predecessor and its goals. Levski was a prominent member of the Legion, but between February and April 1868 he suffered from a gastric condition that required surgery. Bedridden, he could not participate in the Legion's training. After the Legion was again disbanded under political pressure, Levski attempted to reunite with his compatriots, but was arrested in Zaječar and briefly imprisoned. Upon his release he went to Romania, where

From late August 1869 to May the following year, Levski was active in the Romanian capital Bucharest. He was in contact with revolutionary writer and journalist Lyuben Karavelov, whose participation in the foundation of the

From late August 1869 to May the following year, Levski was active in the Romanian capital Bucharest. He was in contact with revolutionary writer and journalist Lyuben Karavelov, whose participation in the foundation of the

Apocryphal and semi-legendary anecdotal stories surround the creation of Levski's Internal Revolutionary Organisation. Persecuted by the Ottoman authorities who offered 500

Apocryphal and semi-legendary anecdotal stories surround the creation of Levski's Internal Revolutionary Organisation. Persecuted by the Ottoman authorities who offered 500

Realising that he was in danger, Levski decided to flee to Romania, where he would meet Karavelov and discuss these events. First, however, he had to collect important documentation from the committee archive in Lovech, which would constitute important evidence if seized by the Ottomans. He stayed at the nearby village inn in

Realising that he was in danger, Levski decided to flee to Romania, where he would meet Karavelov and discuss these events. First, however, he had to collect important documentation from the committee archive in Lovech, which would constitute important evidence if seized by the Ottomans. He stayed at the nearby village inn in

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...

. Dubbed the ''Apostle of Freedom'', Levski ideologised and strategised a revolutionary movement to liberate Bulgaria from Ottoman rule. Levski founded the Internal Revolutionary Organisation, and sought to foment a nationwide uprising through a network of secret regional committees.

Born in the Sub-Balkan town of Karlovo to middle-class parents, Levski became an Orthodox monk

The degrees of Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic monasticism are the stages an Eastern Orthodox monk or nun passes through in their religious vocation.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the process of becoming a monk or nun is intentionally sl ...

before emigrating to join the two Bulgarian Legions in Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hung ...

and other Bulgarian revolutionary groups. Abroad, he acquired the nickname ''Levski'' ("Lionlike"). After working as a teacher in Bulgarian lands, he propagated his views and developed the concept of his Bulgaria-based revolutionary organisation, an innovative idea that superseded the foreign-based detachment strategy of the past. In Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

, Levski helped institute the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee, composed of Bulgarian expatriates. During his tours of Bulgaria, Levski established a wide network of insurrectionary committees. Ottoman authorities, however, captured him at an inn near Lovech and executed him by hanging in Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. ...

.

Levski looked beyond the act of liberation and envisioned a Bulgarian republic of ethnic and religious equality, largely reflecting the liberal ideas of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

and contemporary Western society. He said, "We will be free in complete liberty where the Bulgarian lives: in Bulgaria, Thrace, Macedonia; people of whatever ethnicity live in this heaven of ours, they will be equal in rights to the Bulgarian in everything." Levski held that all religious and ethnic groups live in a free Bulgaria enjoy equal rights., ''170 години''. He is commemorated with monuments in Bulgaria and Serbia, and numerous national institutions bear his name. In 2007, he topped a nationwide television poll as the all-time greatest Bulgarian.

Historical background

The 19th-century Ottoman Empire's economic hardships prompted its personification as the " sick man of Europe". Thereforms

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

planned by the sultans faced insuperable difficulties. Bulgarian nationalism gradually emerged during the mid-19th century with the economic upsurge of Bulgarian merchants and craftsmen, the development of Bulgarian-funded popular education, the struggle for an autonomous Bulgarian Church

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church ( bg, Българска православна църква, translit=Balgarska pravoslavna tsarkva), legally the Patriarchate of Bulgaria ( bg, Българска патриаршия, links=no, translit=Balgarsk ...

and political actions towards the formation of a separate Bulgarian state. The First and Second Serbian Uprisings had laid the foundation of an autonomous Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hung ...

during the late 1810s, and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

had been established as an independent state in 1832, in the wake of the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted ...

. However, support for gaining independence through an armed struggle against the Ottomans was not universal. Revolutionary sentiment was concentrated largely among the more educated and urban sectors of the populace. There was less support for an organized revolt among the peasantry and the wealthier merchants and traders, who feared that Ottoman reprisals would jeopardize economic stability and widespread rural land ownership.

Biography

Early life, education and monkhood

Vasil Levski was born Vasil Ivanov Kunchev on, 18 July, 1837, in the town of Karlovo, within the Ottoman Empire's European province ofRumelia

Rumelia ( ota, روم ايلى, Rum İli; tr, Rumeli; el, Ρωμυλία), etymologically "Land of the Romans", at the time meaning Eastern Orthodox Christians and more specifically Christians from the Byzantine rite, was the name of a hi ...

. He was the namesake of his maternal uncle, Archimandrite

The title archimandrite ( gr, ἀρχιμανδρίτης, archimandritēs), used in Eastern Christianity, originally referred to a superior abbot ('' hegumenos'', gr, ἡγούμενος, present participle of the verb meaning "to lead") wh ...

(superior abbot) Vasil (Василий, ''Vasiliy''). Levski's parents, Ivan Kunchev and Gina Kuncheva (née Karaivanova), came from a family of clergy and craftsmen and were members of the emerging Bulgarian middle class. An eminent but struggling local craftsman, Ivan Kunchev died in 1844. Levski had two younger brothers, Hristo and Petar, and an older sister, Yana; another sister, Maria, died during childhood.

Stara Zagora

Stara Zagora ( bg, Стара Загора, ) is the sixth-largest city in Bulgaria, and the administrative capital of the homonymous Stara Zagora Province.

Name

The name comes from the Slavic root ''star'' ("old") and the name of the medieva ...

, where he attended school and worked as Basil's servant. Afterward, Levski joined a clerical training course. On 7 December 1858, he became an Orthodox monk in the Sopot

Sopot is a seaside resort city in Pomerelia on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea in northern Poland, with a population of approximately 40,000. It is located in Pomeranian Voivodeship, and has the status of the county, being the smallest c ...

monastery under the religious name Ignatius (Игнатий, ''Ignatiy'') and was promoted in 1859 to hierodeacon A hierodeacon (Greek: Ἱεροδιάκονος, ''Ierodiákonos''; Slavonic: ''Ierodiakón''), sometimes translated "deacon-monk", in Eastern Orthodox Christianity is a monk who has been ordained a deacon (or deacon who has been tonsured monk). Th ...

, which later inspired one of Levski's informal nicknames, ''The Deacon'' (Дякона, ''Dyakona'').

First Bulgarian Legion and educational work

Inspired by Georgi Sava Rakovski's revolutionary ideas, Levski left for theSerbian

Serbian may refer to:

* someone or something related to Serbia, a country in Southeastern Europe

* someone or something related to the Serbs, a South Slavic people

* Serbian language

* Serbian names

See also

*

*

* Old Serbian (disambiguat ...

capital Belgrade during the spring of 1862. In Belgrade, Rakovski had been assembling the First Bulgarian Legion )

, war= National awakening of Bulgaria

, image=

, caption=The standard of the Bulgarian Legion

, active=1862–1868

, ideology= Bulgarian nationalism

, leaders= Georgi Sava Rakovski

, groups=

, headquarters=Belgrade, Serbia

, area=

, size=

, parto ...

, a military detachment formed by Bulgarian volunteers and revolutionary workers seeking the overthrow of Ottoman rule. Abandoning his service as a monk, Levski enlisted as a volunteer. At the time, relations between the Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their ...

and their Ottoman suzerains were tense. During the Battle of Belgrade in which Turkish forces entered the city, Levski and the Legion distinguished themselves in repelling them.

Further militant conflicts in Belgrade were eventually resolved diplomatically, and the First Bulgarian Legion was disbanded under Ottoman pressure on 12 September 1862. His courage during training and fighting earned him his nickname Levski ("Lionlike"). After the legion's disbandment, Levski joined Ilyo Voyvoda's detachment at Kragujevac, but returned to Rakovski in Belgrade after discovering that Ilyo's plans to invade Bulgaria had failed.

In the spring of 1863, Levski returned to Bulgarian lands after a brief stay in

In the spring of 1863, Levski returned to Bulgarian lands after a brief stay in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

. His uncle Basil reported him as a rebel to the Ottoman authorities, and Levski was imprisoned in Plovdiv

Plovdiv ( bg, Пловдив, ), is the second-largest city in Bulgaria, standing on the banks of the Maritsa river in the historical region of Thrace. It has a population of 346,893 and 675,000 in the greater metropolitan area. Plovdiv is the c ...

for three months, but released due to the help of the doctor R. Petrov and the Russian vice-consul Nayden Gerov., ''170 години''. On Easter 1864, Levski officially relinquished his religious office. From May 1864 until March 1866, he worked as a teacher in Voynyagovo

Voynyagovo ( bg, Войнягово) is a village in central southern Bulgaria, part of Karlovo Municipality, Plovdiv Province. As of 2008, it has a population of 1,260. The village lies in the Sredna Gora mountains, above sea level.

History

...

near Karlovo; while there, he supported and gave shelter to persecuted Bulgarians and organised patriotic groups among the population. His activity caused suspicion among the Ottoman authorities, and he was forced to move. From the spring of 1866 to the spring of 1867, he taught in Enikyoy and Kongas, two Northern Dobruja villages near Tulcea

Tulcea (; also known by other alternative names) is a city in Northern Dobruja, Romania. It is the administrative center of Tulcea County, and had a population of 73,707 . One village, Tudor Vladimirescu, is administered by the city.

Names

T ...

.

Hitov's detachment and Second Bulgarian Legion

In November 1866, Levski visited Rakovski in Iaşi. Two revolutionary bands led by Panayot Hitov and Filip Totyu had been inciting the Bulgarian diaspora community in Romania to invade Bulgaria and organise anti-Ottoman resistance. On the recommendation of Rakovski, Vasil Levski was selected as the standard-bearer of Hitov's detachment. In April 1867, the band crossed theDanube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , ...

at Tutrakan, moved through the Ludogorie region and reached the Balkan Mountains. After skirmishing, the band fled to Serbia through Pirot

Pirot ( sr-cyr, Пирот) is a city and the administrative center of the Pirot District in southeastern Serbia. According to 2011 census, the urban area of the city has a population of 38,785, while the population of the city administrative are ...

in August.

In Serbia, the government was again favourable towards the Bulgarian revolutionaries' aspirations and allowed them to establish in Belgrade the Second Bulgarian Legion, an organisation similar to its predecessor and its goals. Levski was a prominent member of the Legion, but between February and April 1868 he suffered from a gastric condition that required surgery. Bedridden, he could not participate in the Legion's training. After the Legion was again disbanded under political pressure, Levski attempted to reunite with his compatriots, but was arrested in Zaječar and briefly imprisoned. Upon his release he went to Romania, where

In Serbia, the government was again favourable towards the Bulgarian revolutionaries' aspirations and allowed them to establish in Belgrade the Second Bulgarian Legion, an organisation similar to its predecessor and its goals. Levski was a prominent member of the Legion, but between February and April 1868 he suffered from a gastric condition that required surgery. Bedridden, he could not participate in the Legion's training. After the Legion was again disbanded under political pressure, Levski attempted to reunite with his compatriots, but was arrested in Zaječar and briefly imprisoned. Upon his release he went to Romania, where Hadzhi Dimitar

Dimitar Nikolov Asenov ( bg, Димитър Николов Асенов ; 10 May 1840 – 10 August 1868), better known as Hadzhi Dimitar ( ), was one of the most prominent Bulgarian voivode and revolutionaries working for the Liberation of Bul ...

and Stefan Karadzha were mobilising revolutionary detachments. For various reasons, including his stomach problems and strategic differences, Levski did not participate. In the winter of 1868, he became acquainted with poet and revolutionary Hristo Botev and lived with him in an abandoned windmill near Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north ...

.

Bulgarian tours and work in Romania

Rejecting the emigrant detachment strategy for internal propaganda, Levski undertook his first tour of the Bulgarian lands to engage all layers of Bulgarian society for a successful revolution. On 11 December 1868, he travelled by steamship from Turnu Măgurele toIstanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

, the starting point of a trek that lasted until 24 February 1869, when Levski returned to Romania. During this canvassing and reconnaissance mission, Levski is thought to have visited Plovdiv, Perushtitsa, Karlovo, Sopot, Kazanlak, Sliven, Tarnovo, Lovech, Pleven

Pleven ( bg, Плèвен ) is the seventh most populous city in Bulgaria. Located in the northern part of the country, it is the administrative centre of Pleven Province, as well as of the subordinate Pleven municipality. It is the biggest ...

and Nikopol, establishing links with local patriots.

After a two-month stay in Bucharest, Vasil Levski returned to Bulgaria for a second tour, lasting from 1 May to 26 August 1869. On this tour he carried proclamations printed in Romania by the political figure Ivan Kasabov. They legitimised Levski as the representative of a Bulgarian provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

. Vasil Levski travelled to Nikopol, Pleven, Karlovo, Plovdiv, Pazardzhik, Perushtitsa, Stara Zagora, Chirpan

Chirpan ( bg, Чирпан, ) is a town on the Tekirska River in Stara Zagora Province of south-central Bulgaria. It is the administrative centre of the homonymous Chirpan Municipality. As of 2021, the town had a population of 13,391 down fr ...

, Sliven, Lovech, Tarnovo, Gabrovo, Sevlievo and Tryavna. According to some researchers, Levski established the earliest of his secret committees during this tour, but those assumptions are based on uncertain data.

From late August 1869 to May the following year, Levski was active in the Romanian capital Bucharest. He was in contact with revolutionary writer and journalist Lyuben Karavelov, whose participation in the foundation of the

From late August 1869 to May the following year, Levski was active in the Romanian capital Bucharest. He was in contact with revolutionary writer and journalist Lyuben Karavelov, whose participation in the foundation of the Bulgarian Literary Society

The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (abbreviated BAS; bg, Българска академия на науките, ''Balgarska akademiya na naukite'', abbreviated ''БАН'') is the National Academy of Bulgaria, established in 1869.

The Academy ...

Levski approved in writing. Karavelov's publications gathered a number of followers and initiated the foundation of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC), a centralised revolutionary diasporic organisation that included Levski as a founding member and statute drafter. In disagreement over planning, Levski departed from Bucharest in the spring of 1870 and began to put into action his concept of an internal revolutionary network.

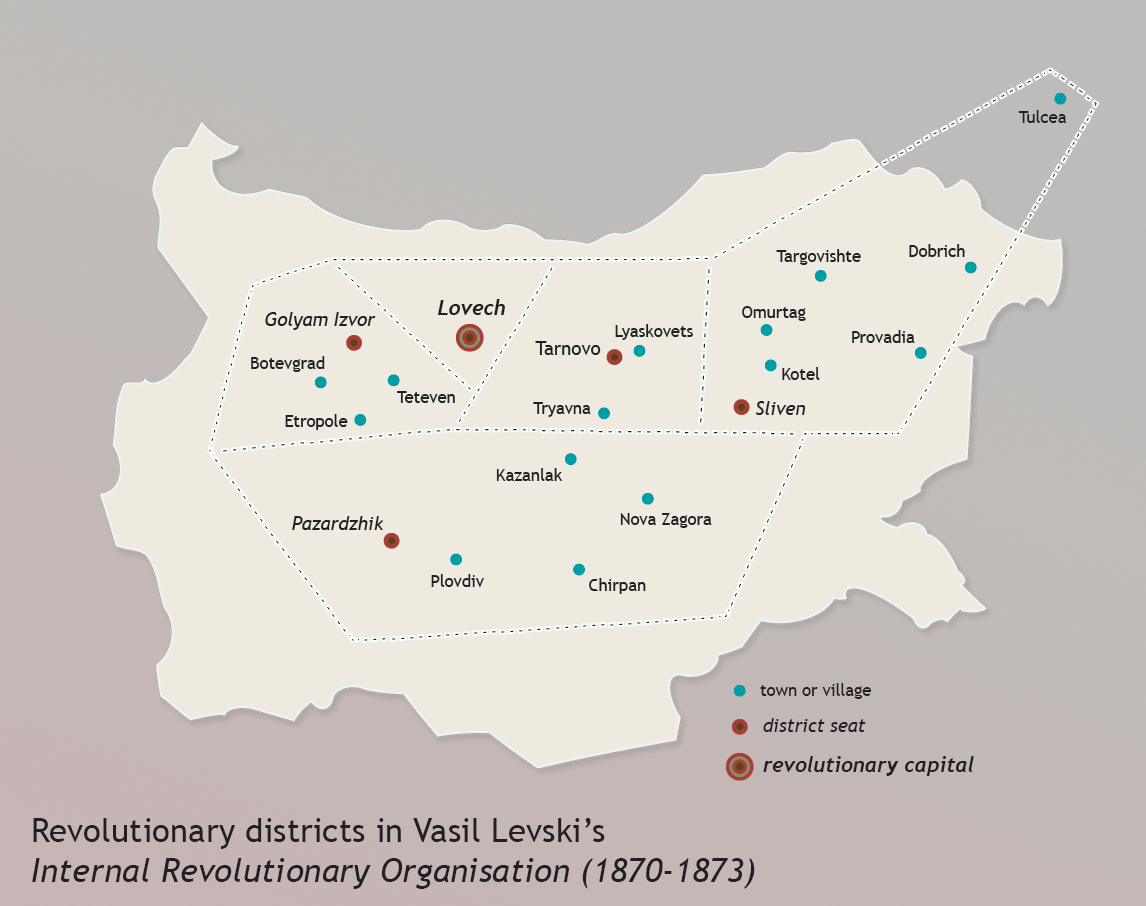

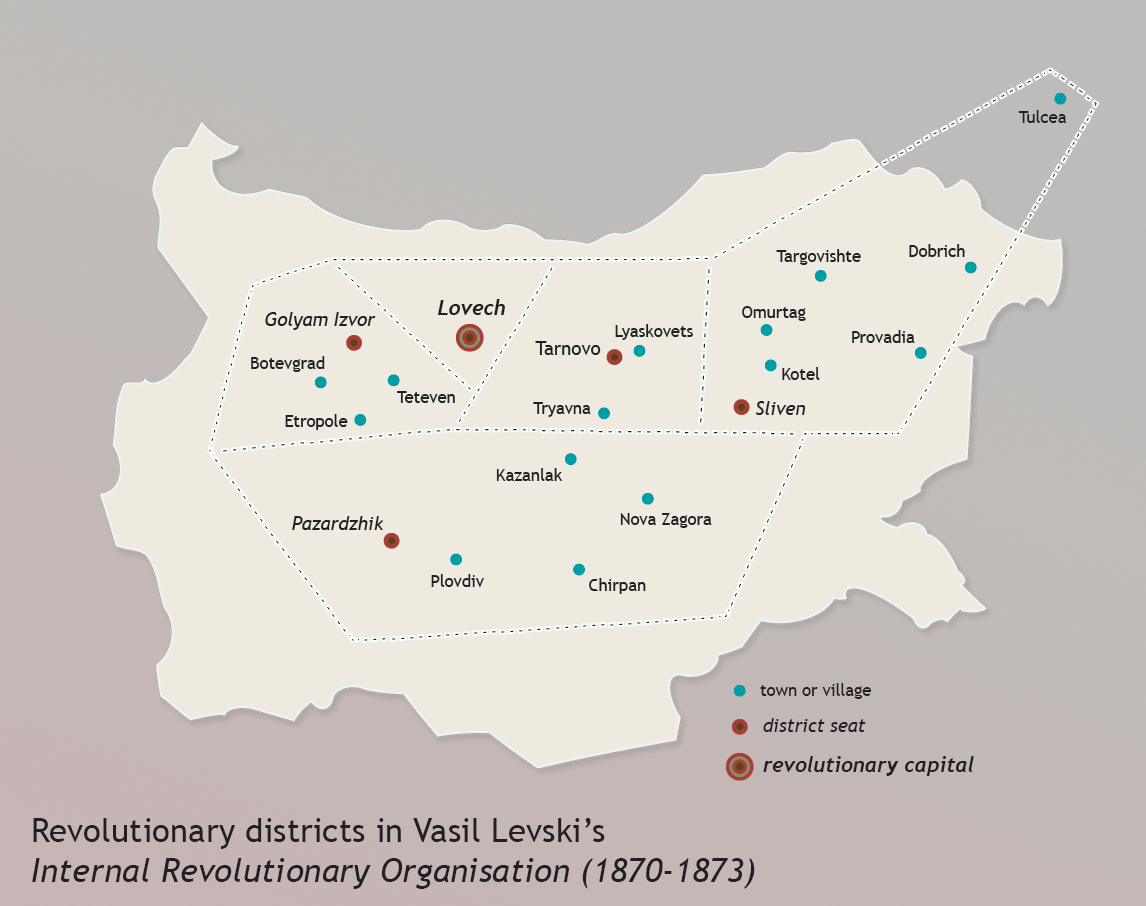

Creation of the Internal Revolutionary Organisation

Despite insufficient documentation of Levski's activities in 1870, it is known that he spent a year and a half establishing a wide network of secret committees in Bulgarian cities and villages. The network, the Internal Revolutionary Organisation (IRO), was centred around the Lovech Central Committee, also called "BRCC in Bulgaria" or the "provisional government". The goal of the committees was to prepare for a coordinated uprising. The network of committees was at its densest in the central Bulgarian regions, particularly around Sofia, Plovdiv and Stara Zagora. Revolutionary committees were also established in some parts ofMacedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

, Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; bg, Добруджа, Dobrudzha or ''Dobrudža''; ro, Dobrogea, or ; tr, Dobruca) is a historical region in the Balkans that has been divided since the 19th century between the territories of Bulgaria and Romania. I ...

and Strandzha and around the more peripheral urban centres Kyustendil, Vratsa and Vidin. IRO committees purchased armaments and organised detachments of volunteers. According to one study, the organisation had just over 1,000 members in the early 1870s. Most members were intellectuals and traders, though all layers of Bulgarian society were represented.

Individuals obtained IRO membership in secrecy: the initiation ritual involved a formal oath of allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to a monarch or a country. In modern republics, oaths are sworn to the country in general, or to the country's constitution. Fo ...

over the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

or a Christian cross, a gun and a knife; treason was punishable by death, and secret police monitored each member's activities. Through clandestine channels of reliable people, relations were maintained with the revolutionary diasporic community. The internal correspondence employed encryption

In cryptography, encryption is the process of encoding information. This process converts the original representation of the information, known as plaintext, into an alternative form known as ciphertext. Ideally, only authorized parties can dec ...

, conventional signs, and fake personal and committee names. Although Levski himself headed the organisation, he shared administrative responsibilities with assistants such as monk-turned-revolutionary Matey Preobrazhenski, the adventurous Dimitar Obshti

Dimitar Obshti ( bg, Димитър Общи) was a 19th-century Bulgarian revolutionary, who fought for the liberation of Bulgaria, Serbia and Crete from the Ottoman Empire, as well as for the '' Risorgimento'' of Italy.

Biography

Obshti ...

, and the young Angel Kanchev.

Apocryphal and semi-legendary anecdotal stories surround the creation of Levski's Internal Revolutionary Organisation. Persecuted by the Ottoman authorities who offered 500

Apocryphal and semi-legendary anecdotal stories surround the creation of Levski's Internal Revolutionary Organisation. Persecuted by the Ottoman authorities who offered 500 Turkish lira

The lira ( tr, Türk lirası; sign: ₺; ISO 4217 code: TRY; abbreviation: TL) is the official currency of Turkey and Northern Cyprus. One lira is divided into one hundred ''kuruş''.

History

Ottoman lira (1844–1923)

The lira, along wit ...

s for his death and 1000 for his capture, Levski resorted to disguises to evade arrest during his travels. For example, he is known to have dyed his hair and to have worn a variety of national costumes. In the autumn of 1871, Levski and Angel Kanchev published the ''Instruction of the Workers for the Liberation of the Bulgarian People'', a BRCC draft statute containing ideological, organisational and penal sections. It was sent out to the local committees and to the diasporic community for discussion. The political and organisational experience that Levski amassed is evident in his correspondence dating from 1871 to 1872; at the time, his views on the revolution had clearly matured.

As IRO expanded, it coordinated its activities more with the Bucharest-based BRCC. On Levski's initiative, a general assembly was called between 29 April and 4 May 1872. At the assembly, the delegates approved a programme and a statute, elected Lyuben Karavelov as the organisation's leader and authorised Levski as the BRCC executive body's only legitimate representative in the Bulgarian lands. After attending the assembly, Levski returned to Bulgaria and reorganised IRO's internal structure in accordance with BRCC's recommendations. Thus, the Lovech Central Committee was reduced to a regular local committee, and the first region-wide revolutionary centres were founded. The lack of funds, however, precipitated the organisation into a crisis, and Levski's one-man judgements on important strategic and tactical matters were increasingly questioned.

Capture and execution

In that situation, Levski's assistant Dimitar Obshti robbed an Ottoman postal convoy in the Arabakonak pass on 22 September 1872, without approval from Levski or the leadership of the movement. While the robbery was successful and provided IRO with 125,000 groschen, Obshti and the other perpetrators were soon arrested. The preliminary investigation and trial revealed the revolutionary organisation's size and its close relations with BRCC. Obshti and other prisoners made a full confession and revealed Levski's leading role. Realising that he was in danger, Levski decided to flee to Romania, where he would meet Karavelov and discuss these events. First, however, he had to collect important documentation from the committee archive in Lovech, which would constitute important evidence if seized by the Ottomans. He stayed at the nearby village inn in

Realising that he was in danger, Levski decided to flee to Romania, where he would meet Karavelov and discuss these events. First, however, he had to collect important documentation from the committee archive in Lovech, which would constitute important evidence if seized by the Ottomans. He stayed at the nearby village inn in Kakrina

Kakrina ( bg, Къкрина) is a village in central northern Bulgaria, part of Lovech Municipality, Lovech Province. It lies in the central Fore-Balkan Mountains, at an altitude of . As of 2008, it has a population of 298.

Kakrina is mainly fam ...

, where he was surprised and arrested on the morning of 27 December 1872. Starting with the writings of Lyuben Karavelov, the most accepted version has been that a priest named Krastyo Nikiforov betrayed Levski to the police. This theory has been disputed by the researchers Ivan Panchovski and Vasil Boyanov for lack of evidence.

Initially taken to Tarnovo for interrogation, Levski was sent to Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. ...

on 4 January. There, he was taken to trial. While he acknowledged his identity, he did not reveal his accomplices or details related to his organisation, taking full blame. Ottoman authorities sentenced Levski to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on 18 February 1873 in Sofia, where the Monument to Vasil Levski now stands. The location of Levski's grave is uncertain, but in the 1980s, writer Nikolay Haytov campaigned for the Church of St. Petka of the Saddlers as Levski's burial place, which the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences concluded as possible yet unverifiable.

Levski's death intensified the crisis in the Bulgarian revolutionary movement, and most IRO committees soon disintegrated. Nevertheless, five years after Levski's hanging, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 secured the liberation of Bulgaria from Ottoman rule in the wake of the April Uprising

The April Uprising ( bg, Априлско въстание, Aprilsko vastanie) was an insurrection organised by the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire from April to May 1876. The regular Ottoman Army and irregular bashi-bazouk units brutally ...

of 1876. The Treaty of San Stefano of 3 March 1878 established the Bulgarian state as an autonomous Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria ( bg, Княжество България, Knyazhestvo Balgariya) was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War e ...

under ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

'' Ottoman suzerainty.

Revolutionary theory and ideas

At the end of the 1860s, Levski developed a revolutionary theory that saw the Bulgarian liberation movement as an armed uprising of all Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire. The insurrection was to be prepared, controlled and coordinated internally by a central revolutionary organisation, which was to include local revolutionary commit