Thomas Swann on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Swann (February 3, 1809 – July 24, 1883) was an American lawyer and

Swann returned to Alexandria after his father's death in 1840, but also continued as a railroad lawyer. Between 1837 and 1843 he was the assistant to

Swann returned to Alexandria after his father's death in 1840, but also continued as a railroad lawyer. Between 1837 and 1843 he was the assistant to

Thomson Francis Mason and Thomas Swann Families papers

at the

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

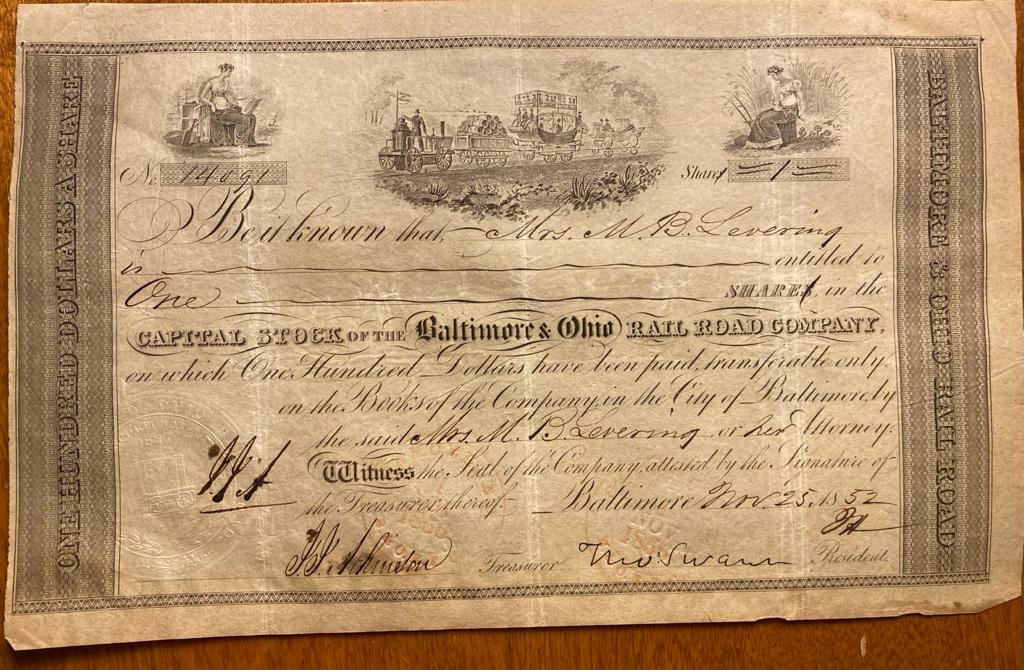

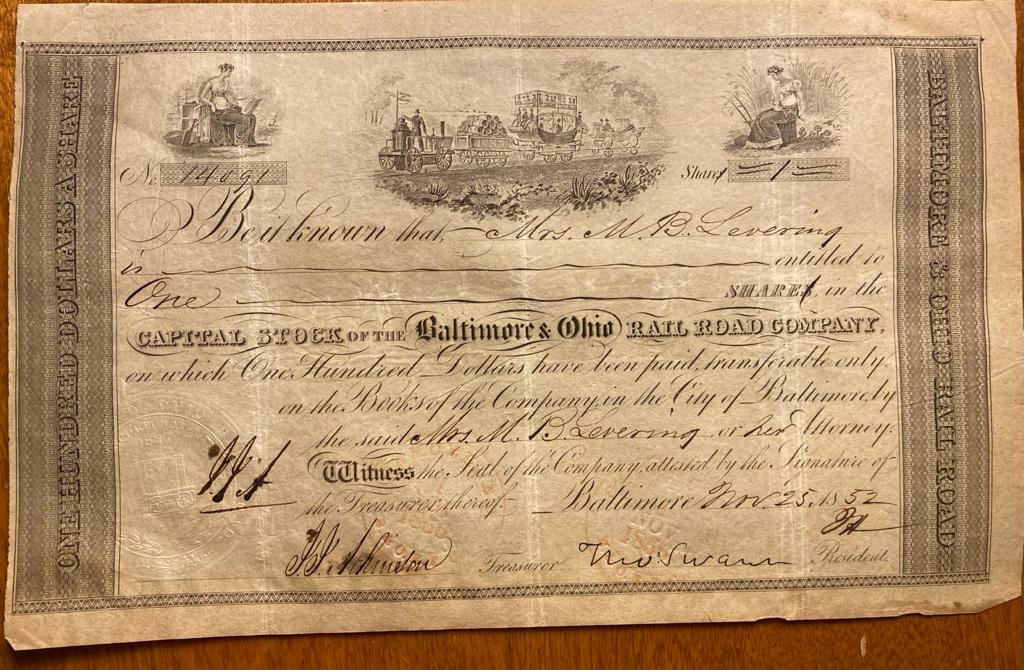

who also was President of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

as it completed track to Wheeling and gained access to the Ohio River Valley. Initially a Know-Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

, and later a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, Swann served as the 19th Mayor of Baltimore

The mayor of Baltimore is the head of the executive branch of the government of the City of Baltimore, Maryland. The Mayor has the duty to enforce city laws, and the power to either approve or veto bills, ordinances, or resolutions passed by the ...

(1856–1860), later as the 33rd Governor of Maryland

The Governor of the State of Maryland is the head of government of Maryland, and is the commander-in-chief of the state's National Guard units. The Governor is the highest-ranking official in the state and has a broad range of appointive powers ...

(1866–1869), and subsequently as U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

("Congressman") from Maryland's 3rd congressional district

Maryland's 3rd congressional district comprises portions of Baltimore, Howard, Montgomery, and Anne Arundel counties, as well as a significant part of the independent city of Baltimore. The seat is currently represented by John Sarbanes, a Dem ...

and then 4th congressional district (1869–1879), representing the Baltimore area.

Early life and career

Swann was born inAlexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in the northern region of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Downto ...

, the fourth son born by the former Jane Byrd Page, a member of one of the First Families of Virginia

First Families of Virginia (FFV) were those families in Colonial Virginia who were socially prominent and wealthy, but not necessarily the earliest settlers. They descended from English colonists who primarily settled at Jamestown, Williamsburg ...

. His mother died three years later after a difficult childbirth. His attorney father, Thomas Swann

Thomas Swann (February 3, 1809 – July 24, 1883) was an American lawyer and Politics of the United States, politician who also was President of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as it completed track to Wheeling, West Virginia, Wheeling and gaine ...

, had served in the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-numbe ...

and with political connections to William Wirt and other Virginia lawyers in the national government, would become United States Attorney for the District of Columbia

The United States Attorney for the District of Columbia (USADC) is the United States Attorney responsible for representing the federal government in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. The U.S. Attorney's Office for the ...

during this man's childhood. Although two of his brothers died between 1825 and 1829, Swann's elder brother Wilson Cary Swann (1806-1876) was educated with him and later rose to prominence as a physician, philanthropist, and social reformer in Philadelphia.

The Swann brothers attended Columbian College (now George Washington University

, mottoeng = "God is Our Trust"

, established =

, type = Private federally chartered research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.8 billion (2022)

, preside ...

) in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, then the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

at Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen Cha ...

. Thomas Jr. studied Ancient and modern languages and mathematics, but was also disciplined for disorderly conduct in 1825 and questioned in a gambling scandal the following year, which may have led him to enroll in a class in moral philosophy from prominent Virginia lawyer George Tucker. He also studied law under his father's guidance.

Career

A Democrat, in 1833 and possibly through his father's connections, Swann secured an appointment from PresidentAndrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

as secretary of the United States Commission to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

(Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and a ...

- later Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

). Also admitted to the Virginia bar, he began following his father's career path by winning election to the Alexandria City council in 1833.

In 1834, Swann married an heiress and moved to Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, where his father's lawyer friend William Wirt had settled, and where Swann later became a railroad lawyer. His bride's British born father, John Sherlock, left a sizeable estate which included interests in French and Neopolitan spoliation claims, as well as 6000 acres of Pennsylvania land, 150 ounces of silver plate, 300 bottles of madeira, plus stock in the Bank of the United States, three Baltimore banks, two turnpikes, a canal in York, Pennsylvania and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

(which had been incorporated in 1827 and in completed track to Harper's Ferry by 1834). His wife's uncle, Robert Gilmor, secured them entry into Baltimore society, although his father experienced financial difficulties after the Panic of 1836 so young Thomas bought 600 to 700 acres of land and the Morven Park plantation home from his father, noting that his father's nemesis Nicholas Biddle likewise was forced to sell property to his sons after the panic. In 1840 the elder Thomas Swann died and this man inherited Morven Park, sixty slaves and his father's law library, and over the next years gradually purchased the rest of what had been his father's land. Meanwhile, this Thomas Swann and his family lived on Franklin Street in Baltimore, and used his late father's Virginia property Morven Park as their summer retreat.

Swann returned to Alexandria after his father's death in 1840, but also continued as a railroad lawyer. Between 1837 and 1843 he was the assistant to

Swann returned to Alexandria after his father's death in 1840, but also continued as a railroad lawyer. Between 1837 and 1843 he was the assistant to Louis McLane

Louis McLane (May 28, 1786 – October 7, 1857) was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, in New Castle County, Delaware, and Baltimore, Maryland. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, a member of the Federalist Party and later th ...

, a veteran politician who served as the railroad's president. In 1844 Swann became Alexandria' tobacco inspector, an important responsibility in that port city which also had railroad ties both to Richmond, and (via a separate station) to Baltimore. In 1846-1847, Swann was the B7O's lobbyist in Richmond, for the franchise the railroad had secured in 1827 was expiring, and its extension through western Virginia was opposed by the powerful political interests of the James River and Kanawha Canal Company. Swann secured the extension on March 6, 1847, the railroad began building to Wheeling, and by October 1848, Swann's large stockholdings in and services to the B&O led to his election as a director, and when McLane retired, he succeeded him as the railroad's president. bY 1850, Swann raised funds in Europe to enable the B&O's extension to the Ohio River, continuing in that position until resigning in 1853. He was chosen as president of the Northwestern Virginia Railroad.

Mayor of Baltimore

1856 election

Swann was first electedMayor of Baltimore

The mayor of Baltimore is the head of the executive branch of the government of the City of Baltimore, Maryland. The Mayor has the duty to enforce city laws, and the power to either approve or veto bills, ordinances, or resolutions passed by the ...

in 1856 as a member of the "Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

" movement (also known as the " American Party") in one of the bloodiest and corrupt elections in state history. He supposedly defeated Democratic challenger Robert Clinton Wright by over a thousand votes.

Many believed that once slavery was abolished in Maryland, African Americans would begin a mass emigration to a new state. As white soldiers returned from Southern battlefields, they came home to find that not only were their slaves gone, but soil exhaustion was causing tobacco crops in southern Maryland to fail. With a growing number of disaffected white men, Swann embarked on a campaign of "Redemption" and "restoring to Maryland a white man's government".

Additionally, Swann enacted a law that encouraged white fisherman to harass black fisherman when he signed into law the state's first ever "Oyster Code":

"And be it acted, that all owners and masters of canoes, boats, or vessels licensed under this article, being White Men, are hereby constituted officers of this state for the purpose of arresting and taking before any judge or Justice of the Peace, any persons who may be engaged in violating any provisions of this article. Furthermore, all such owners and masters are hereby vested with the power to summon posse comitatus

The ''posse comitatus'' (from the Latin for "power of the county/community/guard"), frequently shortened to posse, is in common law a group of people mobilized by the conservator of peace – typically a reeve, sheriff, chief, or another speci ...

to aid in such arrest.""Archives of Maryland, Volume 0384, Page 0178 - Supplement to the Maryland Code, Containing the Acts of the General Assembly, Passed at the Sessions of 1861, 1861-62, 1864, 1865, 1866, and 1867."

Although Maryland was still a "slave state" at the time, the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

did not apply to it, because it was a non-Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

state, having officially remained in the Union; President Lincoln feared that ending slavery there at the height of the Civil War would cause Maryland to leave the Union. Hence, ending slavery there required a state-level referendum. When slavery there was abolished with the adoption of the third Maryland Constitution of 1864

The Maryland Constitution of 1864 was the third of the four constitutions which have governed the U.S. state of Maryland. A controversial product of the Civil War and in effect only until 1867, when the state's present constitution was adopted, ...

, Lincoln's fears were not realized; the war finished without Maryland ever defecting to the Confederacy, although many men from southern Maryland counties and the "Eastern Shore" did fight on the side of the Confederacy.

During the mid-1850s, public order in Baltimore City had often been threatened by the election of candidates of the "Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

" movement which became known as the " American Party". In October 1856 the "Know Nothing" previous incumbent Mayor Samuel Hinks

Samuel Hinks (May 1, 1815 – November 30, 1887) was Mayor of Baltimore, Maryland, from 1854 to 1856. He was a member of the Know Nothing party. He was succeeded in 1856 by fellow Know Nothing Thomas Swann.

Early life

Samuel Hinks was born ...

was pressed by Baltimoreans to order the Maryland State Militia in readiness to maintain order during the mayoral and municipal elections, as violence was anticipated. Hinks duly gave State Militia general George H. Steuart the order, but he soon rescinded it. As a result, violence broke out on polling day, with shots exchanged by competing mobs. In the 2nd and 8th Wards several citizens were killed, and many wounded. In the 6th ward artillery was used, and a pitched battle fought on Orleans Street in East Baltimore/Jonestown

The Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, better known by its informal name "Jonestown", was a remote settlement in Guyana established by the Peoples Temple, a U.S.–based cult under the leadership of Jim Jones. Jonestown became internationall ...

/Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

neighborhoods between "Know Nothings" and rival Democrats, raging for several hours. The result of the election, in which voter fraud was widespread, was a victory for Swann by around 9,000 votes.

1857 election

In 1857, fearing similar violence at the upcoming elections, Governor Thomas W. Ligon ordered commanding General George H. Steuart of the Maryland State Militia to hold theFirst Light Division, Maryland Volunteers

The First Light Division of Maryland Volunteers was a militia unit based in Baltimore and formed in around 1841. Its commander was the militia general George H. Steuart. Elements of the division participated in the suppression of John Brown's rai ...

in readiness. Swann's ally, fellow UVa Unionist and Know-Nothing Congressman Henry Winter Davis criticized Ligon's action both for subverting local authority and as an attempt to swing the election to the Democrats. Mayor Swann, this time running for re-election, successfully argued for a compromise measure involving special police forces to prevent disorder, and Steuart's militia were stood down. This time, although there was less violence than in 1856, the results of the vote were again compromised, and the "Know-Nothings

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

" took many state offices in the heavily disputed balloting.

1858 election

He was re-elected in 1858, again with widespread violence prevalent, and won by over 19,000 votes due to a large amount of voter intimidation. There were a great deal ofinternal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

and urban modernizations during Swann's tenure as mayor. The long-time colonial-era various in-fighting problems and competitive volunteer independent firefighting companies since 1763 (under a loose confederation of the "Baltimore City United Fire Department" of 1835) were replaced in 1858 with paid professional firefighters with the organization of the modern current Baltimore City Fire Department

The Baltimore City Fire Department (BCFD) provides fire protection and emergency medical services to the city of Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1797 and established in 1859, the Baltimore City Fire Department covers an area of o ...

, and were given steam-powered fire engines and a better emergency telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

alarm system. His office also oversaw the creation of the horse-drawn streetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport are ...

system in Baltimore replacing the older omnibuses, the purchase from the Col. Nicholas Rogers estate and creation of the large tract for Druid Hill Park

Druid Hill Park is a urban park in northwest Baltimore, Maryland. Its boundaries are marked by Druid Park Drive (north), Swann Drive and Reisterstown Road (west and south), and the Jones Falls Expressway / Interstate 83 (east).Jones Falls

The Jones Falls is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 stream in Maryland. It is impounded to create Lake Roland before running through the city of Baltim ...

. Following the municipal purchase of the former private Baltimore Water Company, (since 1804), saw the replacement of its old wooden pipes and aging inadequate infrastructure with the beginnings of two water-sewage construction projects along the upper Jones Falls

The Jones Falls is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 stream in Maryland. It is impounded to create Lake Roland before running through the city of Baltim ...

. Following was the major public works project of the construction of the dam at the new Lake Roland Reservoir along with the organization of a new city water board and extension of new waterworks service into new outlying areas of the growing metropolis. The "Basin" ( Baltimore Inner Harbor) was dredged at 20 feet depth during his term as governor, and several new schools were added to the city. The former constables and "City Night Watch" system from 1784 were replaced by a newly organized Baltimore City Police Department

The Baltimore Police Department (BPD) is the municipal police department of the city of Baltimore, Maryland. Dating back to 1784, the BPD, consisting of 2,935 employees in 2020, is organized into nine districts covering of land and of waterway ...

under then modern principles was established and given new uniforms, weapons and training (later placed under supervision and appointment powers of the governor in 1860 to the 1990s). To provide better street lighting, the offices of Superindendents of Lamps with the then existing gas system was created.

Violence was greatly prevalent during Swann's term as mayor, especially during election campaigns. Then Maryland Governor Thomas W. Ligon sought Swann's assistance to try to avoid "Know Nothing" riots during the 1856 Presidential elections, but little was resolved during the meeting, and continued riots ensued during the night of the election wounding and killing many. Ligon criticized Swann for not taking the necessary precautions, recalling the event as partisans "engaged; arms of all kinds were employed; and bloodshed, wounds, and death, stained the record of the day, and added another page of dishonor to the annals of the distracted city". This continued to contribute to Baltimore's oft-stated ignoble reputation and nickname of "Mobtown", acquired since the anti-war riots of 1812. Gov. Ligon did not cooperate with Mayor Swann during the state elections of 1857, and immediately imposed martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

upon Baltimore City before election day had begun. Swann was angered, and insisted this was not necessary, but, recalling the events one year earlier, Ligon refused to lift the martial law status.

Governor of Maryland

In 1860, Swann left the American Party, which dissolved, and joined the merged war-time Union Party. In 1864, he was unanimously nominated as the 33rdGovernor of Maryland

The Governor of the State of Maryland is the head of government of Maryland, and is the commander-in-chief of the state's National Guard units. The Governor is the highest-ranking official in the state and has a broad range of appointive powers ...

during its nomination convention. He won election with lieutenant-governor running mate Christopher C. Cox by over 9,000 votes. The only governor elected under the Maryland Constitution of 1864

The Maryland Constitution of 1864 was the third of the four constitutions which have governed the U.S. state of Maryland. A controversial product of the Civil War and in effect only until 1867, when the state's present constitution was adopted, ...

, Swann took the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Such ...

on January 11, 1865, but did not enter into the duties of the office until one year later (under that constitution, the governor chosen in the November 1864 election could not assume the office until the completion of the term of his predecessor, Augustus W. Bradford, in January 1866); he served until January 1869. In his inaugural address, he encouraged reunion in the State following the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, and voiced his opposition to slavery, deeming it "a stumbling block in the way of uradvancement".

Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

of Maryland criticized Swann for supporting the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

policies of Democratic and 17th President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, and refusing to adopt their proposals. He eventually parted with the Republicans and joined the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

during his term as governor. He had strongly opposed requiring the "ironclad" loyalty oath and registration laws promoted by the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

for former Confederates in the state.

In 1867, the General Assembly of Maryland

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives and the lower chamber ...

nominated Swann to succeed John A. J. Creswell

John Andrew Jackson Creswell (November 18, 1828December 23, 1891) was an American politician and abolitionist from Maryland, who served as United States Representative, United States Senator, and as Postmaster General of the United States appo ...

to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

. But, Radical Republicans had gained control of the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

in 1867, and refused to allow Swann admission to the Senate because he had switched parties. The Democrats in Maryland began to fear that, if Swann left, the Maryland lieutenant governor, a Radical Republican, might place Maryland under a military, Reconstruction government and temporarily disfranchise whites who had served in the Confederacy. Also, they did not want to lose reforms made by Swann with other voting rights. Rather than fight the Radicals in Congress to gain a seat, Swann was convinced by Democrats to remain as governor and turn down the Senate seat.

Swann supported internal improvements to state infrastructure, especially after the war, and he is credited with greatly improving the facilities at the Baltimore Port and Harbor. He also encouraged immigration, and the immediate emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchis ...

of slaves following the War. By 1860, 49% of blacks in Maryland were already free, giving them a substantial position and economic strength in the years following the war.

U.S. Congressional career and final years

In 1868, Swann was elected to Congress fromMaryland's 3rd congressional district

Maryland's 3rd congressional district comprises portions of Baltimore, Howard, Montgomery, and Anne Arundel counties, as well as a significant part of the independent city of Baltimore. The seat is currently represented by John Sarbanes, a Dem ...

, gaining re-election and serving until 1873. With redistricting changes, he was elected in 1873 from Maryland's 4th congressional district

Maryland's 4th congressional district comprises portions of Prince George's County and Anne Arundel County. The seat is represented by Anthony Brown, a Democrat.

The district includes most of the majority-black precincts on the Maryland side o ...

, serving three terms until 1879. In the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

, Swann was chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs (Forty-fourth and Forty-fifth Congresses).

Personal life

Swann married twice. In 1843, his first wife, the former Elizabeth Gilmer Sherlock (1814-1876), bore a daughter, Elizabeth Gilmer Swann, who was their only child to reach adulthood. In 1878, the widower married Josephine Ward Thomson, daughter of Representative ("Congressman") Aaron Ward and widow of U.S. SenatorJohn Renshaw Thomson

John Renshaw Thomson (September 25, 1800September 12, 1862) was an American merchant and politician from New Jersey.

Life

Thomson was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the son of Edward Thomson (1771-1853) and Ann Renshaw (1773-1842). His fath ...

, but they had no children.

Death and legacy

Swann died on his estate, " Morven Park", nearLeesburg, Virginia

Leesburg is a town in the state of Virginia, and the county seat of Loudoun County. Settlement in the area began around 1740, which is named for the Lee family, early leaders of the town and ancestors of Robert E. Lee. Located in the far northea ...

. He is interred in the landmark Green Mount Cemetery

Green Mount Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Established on March 15, 1838, and dedicated on July 13, 1839, it is noted for the large number of historical figures interred in its grounds as well as many ...

(southeast of Maryland Route 45

Maryland Route 45 (MD 45) is a state highway in the U.S. state of Maryland. Known for most of its length as York Road, the state highway runs from U.S. Route 1 (US 1) and US 40 Truck in Baltimore north to the Pennsylvania state line in Mary ...

and East North Avenue) of Baltimore. In eulogy, the influential ''" The Sun"'' newspaper of Baltimore criticized his early political errors, but credited him as "a great mayor, conferring inestimable benefits on the city he governed; not only was he a wise and beneficent governor to the oppressed portion of the citizens of the State, but he was one of the most useful and influential Congressmen this State or city ever had." Some of his family's papers are held by the University of Maryland library.

Swann Park, off of South Hanover Street (Maryland Route 2

Maryland Route 2 (MD 2) is the longest state highway in the U.S. state of Maryland. The route runs from Solomons Island in Calvert County north to an intersection with U.S. Route 1 (US 1)/ US 40 Truck ( North Avenue) in Baltimore. The route ...

) in the South Baltimore/Spring Gardens area, adjacent to the eastern waterfront of Middle Branch (Smith and Ridgley's Coves) of the Patapsco River

The Patapsco River mainstem is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 river in central Maryland that flows into the Chesapeake Bay. The river's tidal port ...

is named for him and also serves as an occasional athletic home for the former Southern High School (now Digital Harbor High School

Digital Harbor High School is a magnet high school located in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Occupying the campus of the former Southern High School, it is currently one of two secondary schools and a comprehensive high school that special ...

). Nearby are large monumental gas storage tanks for the Baltimore Gas and Electric Company.

In Virginia, both his childhood home, now called the "Swann-Daingerfield House" and Morven Park still exist (although expanded by later owners) and have been listed on the National Register for Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

since the 1970s. In addition, Alexandria named "Swann Avenue" near the former Potomac Railroad Yards, after him or the family.

References

* * * * *External links

Thomson Francis Mason and Thomas Swann Families papers

at the

University of Maryland Libraries

The University of Maryland Libraries is the largest university library in the Washington, D.C. - Baltimore area. The university's library system includes eight libraries: six are located on the College Park campus, while the Severn Library, an of ...

Further reading

* Describes Swann's career in the American Party in the 1850s. * Details the relationship between American Party politicians and the rowdy clubs affiliated with them in Baltimore during Swann's tenure as mayor. It includes a great deal of information on Swann and his accomplishments in office. , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Swann, Thomas 1809 births 1883 deaths Governors of Maryland Mayors of Baltimore History of slavery in Maryland Politicians from Baltimore Baltimore and Ohio Railroad people Maryland Know Nothings 19th-century American railroad executives Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Maryland Republican Party governors of Maryland Columbian College of Arts and Sciences alumni 19th-century American politicians People from Leesburg, Virginia Page family of Virginia