Thomas Dudley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

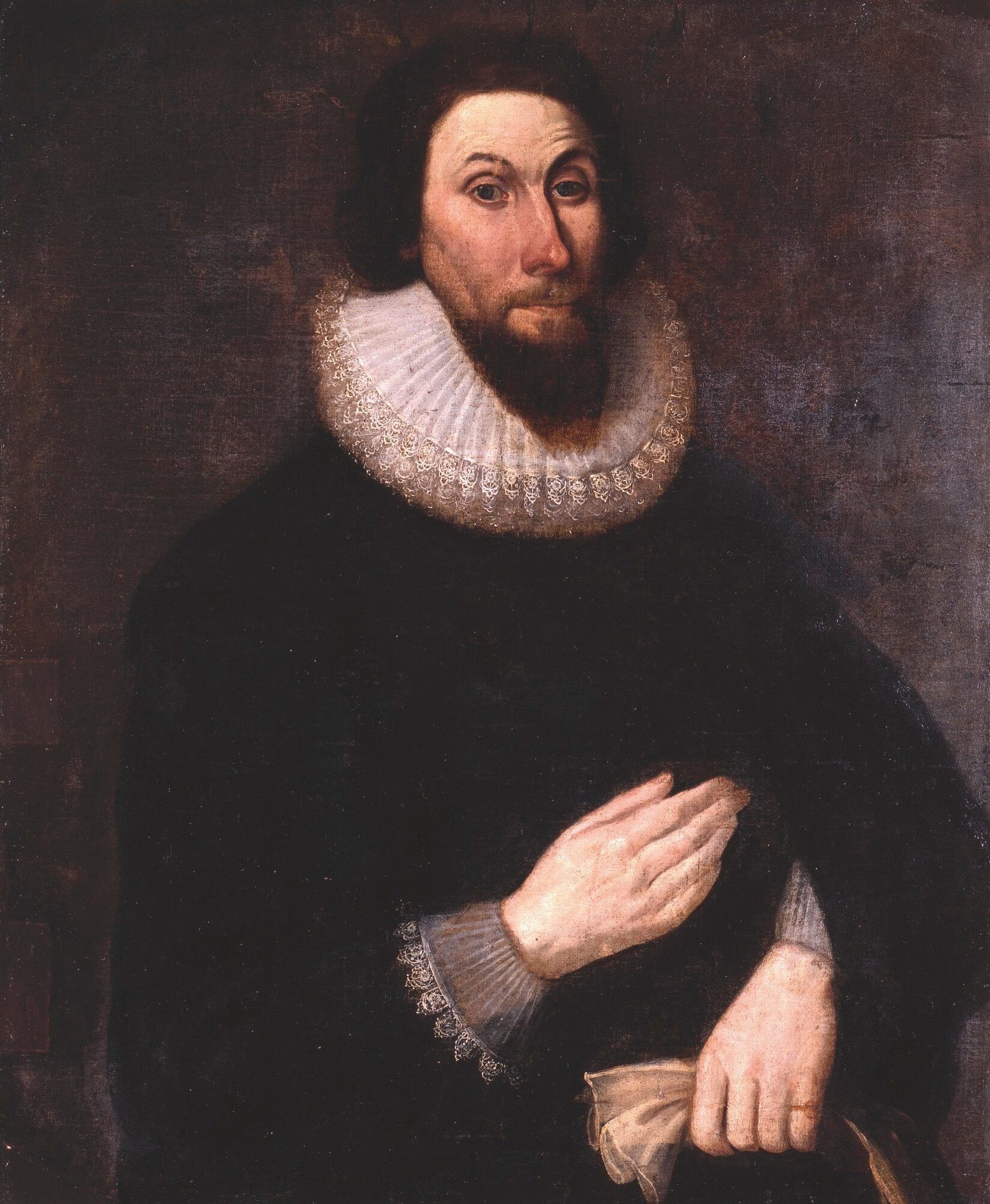

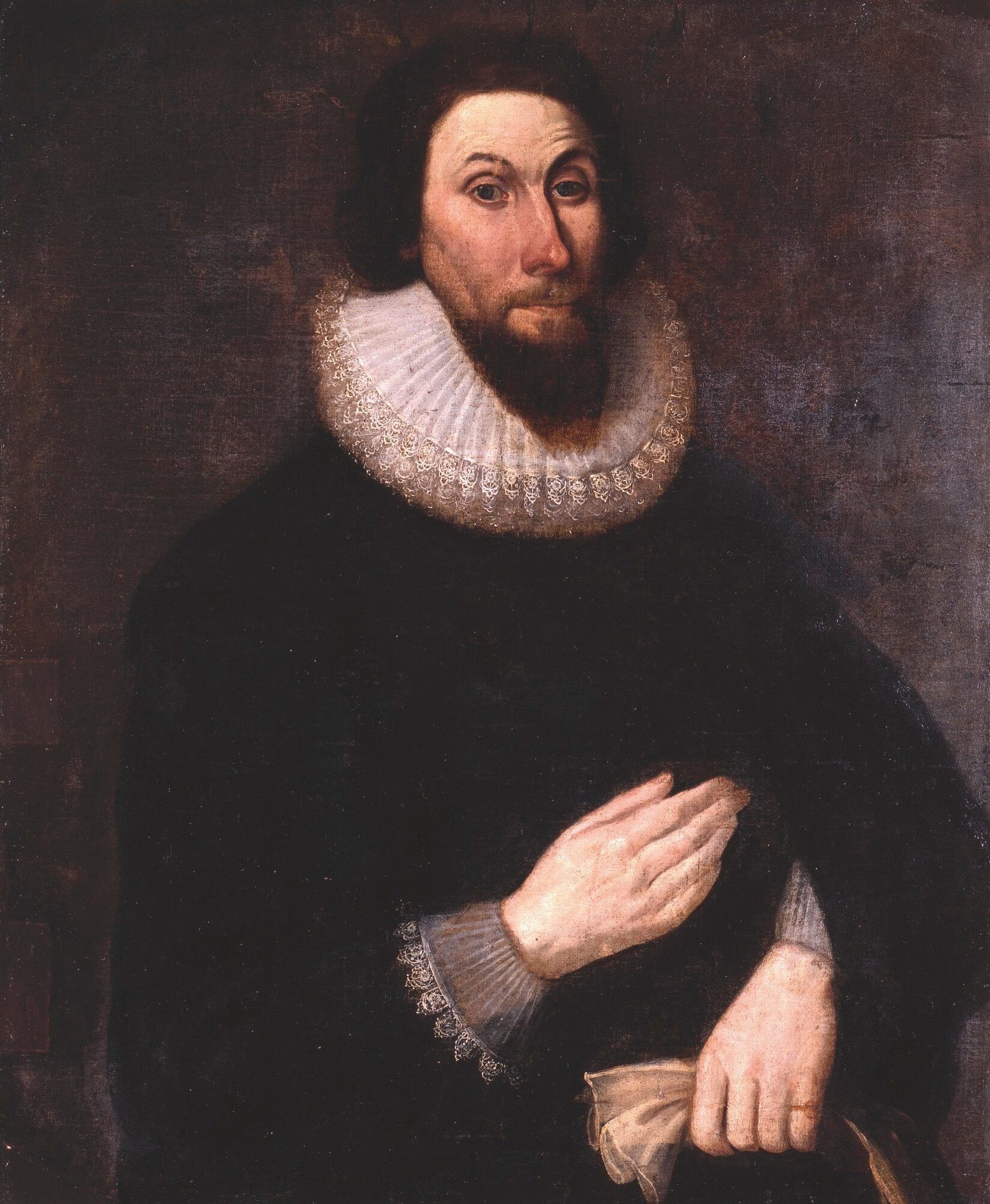

Thomas Dudley (12 October 157631 July 1653) was a

Thomas Dudley was born in

Thomas Dudley was born in

In the spring of 1631 the leadership agreed to establish the colony's capital at Newtowne (near present-day

In the spring of 1631 the leadership agreed to establish the colony's capital at Newtowne (near present-day

In 1635, and for the four following years, Dudley was elected either as deputy governor or as a member of the council of assistants. The governor in 1636 was Henry Vane, and the colony was split over the actions of

In 1635, and for the four following years, Dudley was elected either as deputy governor or as a member of the council of assistants. The governor in 1636 was Henry Vane, and the colony was split over the actions of

In 1649 Dudley was appointed once again to serve as a commissioner and president of the

In 1649 Dudley was appointed once again to serve as a commissioner and president of the

"The Mystery of Thomas Dudley's Paternal Ancestors"

H. Allen Curtis

The Eagle Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dudley, Thomas 1576 births 1653 deaths Colonial governors of Massachusetts Lieutenant Governors of colonial Massachusetts Harvard University people New England Puritanism Politicians from Boston People from West Northamptonshire District American Puritans Dudley family, Thomas 16th-century English people 17th-century English people People from colonial Boston Kingdom of England emigrants to Massachusetts Bay Colony Burials in Boston People from Cambridge, Massachusetts

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

colonial magistrate who served several terms as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

. Dudley was the chief founder of Newtowne, later Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, and built the town's first home. He provided land and funds to establish the Roxbury Latin School

The Roxbury Latin School is a private boys' day school that was founded in 1645 in the town of Roxbury (now a neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts) by the Rev. John Eliot under a charter received from King Charles I of England. It bills ...

, and signed Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

's new charter during his 1650 term as governor. Dudley was a devout Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

who was opposed to religious views not conforming with his. In this he was more rigid than other early Massachusetts leaders like John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

, but less confrontational than John Endecott

John Endecott (also spelled Endicott; before 1600 – 15 March 1664/1665), regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He serv ...

.

The son of a military man who died when he was young, Dudley saw military service himself during the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estim ...

, and then acquired some legal training before entering the service of his likely kinsman the Earl of Lincoln. Along with other Puritans in Lincoln's circle, Dudley helped organize the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, sailing with Winthrop in 1630. Although he served only four one-year terms as governor of the colony, he was regularly in other positions of authority.

Dudley's daughter Anne Bradstreet

Anne Bradstreet ( née Dudley; March 8, 1612 – September 16, 1672) was the most prominent of early English poets of North America and first writer in England's North American colonies to be published. She is the first Puritan figure in ...

(1612–1672) was a prominent early American poet. One of the gates of Harvard Yard

Harvard Yard, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is the oldest part of the Harvard University campus, its historic center and modern crossroads. It contains most of the freshman dormitories, Harvard's most important libraries, Memorial Church, sever ...

, which existed from 1915 to 1947, was named in his honor, and Harvard's Dudley House is named for the family, as is the town of Dudley, Massachusetts

Dudley is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 11,921 at the 2020 census.

History

Dudley was first settled in 1714 and was officially incorporated in 1732. The town was named for landholders Paul and Will ...

.

Early years

Yardley Hastings

Yardley Hastings is a village and civil parish in the English county of Northamptonshire. It is located south-east of the county town of Northampton and is skirted on its south side by the main A428 road to Bedford.

History

The village's name ...

, a village near Northampton, England

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

, on 12 October 1576, to Roger

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ( ...

and Susanna (Thorne) Dudley.Anderson, p. 584 The family has long asserted connections to the Sutton-Dudleys of Dudley Castle

Dudley Castle is a ruined fortification in the town of Dudley, West Midlands, England. Originally a wooden motte and bailey castle built soon after the Norman Conquest, it was rebuilt as a stone fortification during the twelfth century but su ...

(Duke of Northumberland

Duke of Northumberland is a noble title that has been created three times in English and British history, twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of Great Britain. The current holder of this title is Ralph Percy, 12th Duke ...

, Earls of Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined with Leamington Spa and Whi ...

and Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

, Viscounts Lisle, and Barons Dudley); there is a similarity in their coats of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its wh ...

,Jones, pp. 3–10 but association beyond probable common ancestry has not yet been conclusively demonstrated.Anderson, p. 585 Roger Dudley, a captain in the English army, was apparently killed in battle. It was for some time believed he was killed in the 1590 Battle of Ivry

The Battle of Ivry was fought on 14 March 1590, during the French Wars of Religion. The battle was a decisive victory for Henry IV of France, leading French royal and English forces against the Catholic League by the Duc de Mayenne and Spanis ...

,Jones, p. 3 but Susanna Dudley is known already to have been widowed by 1588. The 1586 battle of Zutphen

The Battle of Zutphen was fought on 22 September 1586, near the village of Warnsveld and the town of Zutphen, the Netherlands, during the Eighty Years' War. It was fought between the forces of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, aided ...

has also been suggested as the occasion of Roger Dudley's death.Richardson et al, p. 280

Like many other young men of good birth Thomas Dudley became a page

Page most commonly refers to:

* Page (paper), one side of a leaf of paper, as in a book

Page, PAGE, pages, or paging may also refer to:

Roles

* Page (assistance occupation), a professional occupation

* Page (servant), traditionally a young m ...

, in his case in the household of William, Baron Compton at nearby Castle Ashby

Castle Ashby is the name of a civil parish, an estate village and an English country house in rural Northamptonshire. Historically the village was set up to service the needs of Castle Ashby House, the seat of the Marquess of Northampton. The v ...

. Later he raised a company of men following a call to arms by Queen Elizabeth, and served in the English army led by Sir Arthur Savage fighting with King Henry IV of France during the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estim ...

. He fought the Spanish at the Siege of Amiens

The siege of Amiens (French: Siège d'Amiens) was a siege and battle fought during the Franco-Spanish War (1595–1598), as part of both the French Wars of Religion and the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604), between 13 May and 25 September 1597.Jacq ...

in 1597 which in September surrendered and was the final action of the war.

After he was discharged from his military service, Dudley returned to Northamptonshire.Jones, p. 24 He then entered the service of Sir Augustine Nicolls, a relative of his mother's, as a clerk. Nicolls, a lawyer and later a judge, was recognized for his honesty at a time when many judges were susceptible to bribery

Bribery is the Offer and acceptance, offering, Gift, giving, Offer and acceptance, receiving, or Solicitation, soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty. With reg ...

and other malfeasance. He was also sympathetic to the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

cause; the exposure to legal affairs and Nicolls' religious views probably had a significant influence on Dudley. After Nicolls' sudden death in 1616, Dudley took a position with Theophilus Clinton, 4th Earl of Lincoln

Theophilus Clinton, 4th Earl of Lincoln, KB (1599 – 21 May 1667), styled Lord Clinton until 1619, was an opponent of Charles I during and preceding the English Civil War.

Family

The eldest son of the 3rd Earl of Lincoln and Elizabeth Knyve ...

, serving as a steward responsible for managing some of the earl's estates. Although there is a likely blood connection, the reason for the appointment may be that Dudley's soldier grandfather Henry had served under Edward Clinton, 1st Earl of Lincoln

Edward Fiennes, or Clinton, 1st Earl of Lincoln KG (151216 January 1584/85) was an English landowner, peer, and Lord High Admiral. He rendered valuable service to four of the Tudor monarchs.

Family

Edward Clinton, or Fiennes, was born a ...

. The earl's estate in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

was a center of Nonconformist

Nonconformity or nonconformism may refer to:

Culture and society

* Insubordination, the act of willfully disobeying an order of one's superior

*Dissent, a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or entity

** ...

thought, and Dudley was already recognized for his Puritan virtues by the time he entered the earl's service. According to Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting H ...

's biography of Dudley, he successfully disentangled a legacy of financial difficulties bequeathed to the earl, and the earl consequently came to depend on Dudley for financial advice. Dudley's services were not entirely pecuniary in nature: he is also said to have had an important role in securing the engagement of Clinton to Lord Saye's daughter. In 1622, Dudley acquired the assistance of Simon Bradstreet

Simon Bradstreet (baptized March 18, 1603/4In the Julian calendar, then in use in England, the year began on March 25. To avoid confusion with dates in the Gregorian calendar, then in use in other parts of Europe, dates between January and Ma ...

who was eventually drawn to Dudley's daughter Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

. The two were married six years later, when she was 16.

Dudley was briefly out of Lincoln's service between about 1624 and 1628. During this time he lived with his growing family in Boston, Lincolnshire

Boston is a market town and inland port in the borough of the same name in the county of Lincolnshire, England. Boston is north of London, north-east of Peterborough, east of Nottingham, south-east of Lincoln, south-southeast of Hull ...

, where he likely was a parishioner at St Botolph's Church, where John Cotton preached. The Dudleys were known to be back on Lincoln's estate in 1628, when his daughter Anne came down with smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and was treated there.

Massachusetts Bay Colony

In 1628 Dudley and other Puritans decided to form theMassachusetts Bay Company

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, with a view toward establishing a Puritan colony in North America. Dudley's name does not appear on the land grant issued to the company that year, but he was almost certainly involved in the formative stages of the company, whose investors and supporters included many individuals in the Earl of Lincoln's circle. The company sent a small group of colonists led by John Endecott

John Endecott (also spelled Endicott; before 1600 – 15 March 1664/1665), regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He serv ...

to begin building a settlement, called Salem, on the shores of Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

; a second group was sent in 1629.Hurd, p. vii The company acquired a royal charter in April 1629, and later that year made the critical decision to transport the charter and the company's corporate governance to the colony. The Cambridge Agreement The Cambridge Agreement''T ...

, which enabled the emigrating shareholders to buy out those that remained behind, may have been written by Dudley. In October 1629 John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

was elected governor, and John Humphrey was chosen as his deputy. However, as the fleet was preparing to sail in March 1630, Humphrey decided he would not leave England immediately, and Dudley was chosen as deputy governor in his place.

Dudley and his family sailed for the New World on the ''Arbella

''Arbella'' or ''Arabella'' was the flagship of the Winthrop Fleet on which Governor John Winthrop, other members of the Company (including William Gager), and Puritan emigrants transported themselves and the Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Co ...

'', the flagship of the Winthrop Fleet

The Winthrop Fleet was a group of 11 ships led by John Winthrop out of a total of 16 funded by the Massachusetts Bay Company which together carried between 700 and 1,000 Puritans plus livestock and provisions from England to New England over the ...

, on 8 April 1630 and arrived in Salem Harbour on 12 June. Finding conditions at Salem inadequate for establishing a larger colony, Winthrop and Dudley led forays into the Charles River

The Charles River ( Massachusett: ''Quinobequin)'' (sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles) is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton to Boston along a highly meandering route, that doubles b ...

watershed, but were apparently unable to immediately agree on a site for the capital. With limited time to establish themselves, and concerns over rumors of potential hostile French action, the leaders decided to distribute the colonists in several places in order to avoid presenting a single target for hostilities. The Dudleys probably spent the winter of 1630–31 in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, which was where the leadership chose to stay after its first choice, Charlestown, was found to have inadequate water. A letter Dudley wrote to the Countess of Lincoln in March 1631 narrated the first year's experience of the colonists that arrived in Winthrop's fleet in an intimate tone befitting a son or suitor as much as a servant. It appeared in print for the first time in a 1696 compilation of early colonial documents by Joshua Scottow.

Founding of Cambridge

Harvard Square

Harvard Square is a triangular plaza at the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue, Brattle Street and John F. Kennedy Street near the center of Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. The term "Harvard Square" is also used to delineate the busin ...

in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

), and the town was surveyed and laid out. Dudley, Simon Bradstreet, and others built their houses there, but to Dudley's anger, Winthrop decided to build in Boston. This decision caused a rift between Dudley and Winthrop; it was serious enough that in 1632 Dudley resigned his posts and considered returning to England. After the intercession of others, the two reconciled and Dudley retracted his resignations. Winthrop reported that " er after they kept peace and good correspondency in love and friendship."Moore, p. 284 During the dispute, Dudley also harshly questioned Winthrop's authority as governor for a number of actions done without consulting his council of assistants. Dudley's differences with Winthrop came to the fore again in January 1636, when other magistrates orchestrated a series of accusations that Winthrop had been overly lenient in his judicial decisions.

In 1632 Dudley, at his own expense, erected a palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a fence or defensive wall made from iron or wooden stakes, or tree trunks, and used as a defensive structure or enclosure. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymology

''Palisade' ...

around Newtowne (which was renamed Cambridge in 1636) that enclosed of land, principally as a defense against wild animals and Indian raids. The colony agreed to reimburse him by imposing taxes upon all of the area communities. The meetings occasioned by this need are among the first instances of a truly representative government

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a types of democracy, type of democracy where elected people Representation (politics), represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern liberal democr ...

in North America, when each town chose two representatives to advise the governor on the subject. This principle was extended to govern the colony as a whole in 1634, the year Dudley was first elected governor. During this term the colony established a committee to oversee military affairs and to manage the colony's munitions.

The colony came under legal threat in 1632, when Sir Ferdinando Gorges

Sir Ferdinando Gorges ( – 24 May 1647) was a naval and military commander and governor of the important port of Plymouth in England. He was involved in Essex's Rebellion against the Queen, but escaped punishment by testifying against the m ...

, attempting to revive an earlier claim to the territory, raised issues of the colony's charter and governance with the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

of King Charles I. When the colony's governing magistrates drafted a response to the charges raised by Gorges, Dudley was alone in opposing language referring to the king as his "sacred majesty", and to bishops of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

as "Reverend Bishops". Although a ''quo warranto

In law, especially English and American common law, ''quo warranto'' (Medieval Latin for "by what warrant?") is a prerogative writ requiring the person to whom it is directed to show what authority they have for exercising some right, power, or ...

'' writ was issued in 1635 calling for the charter to be returned to England, the king's financial straits prevented it from being served, and the issue eventually died out.

Anne Hutchinson affair

In 1635, and for the four following years, Dudley was elected either as deputy governor or as a member of the council of assistants. The governor in 1636 was Henry Vane, and the colony was split over the actions of

In 1635, and for the four following years, Dudley was elected either as deputy governor or as a member of the council of assistants. The governor in 1636 was Henry Vane, and the colony was split over the actions of Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (née Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her ...

. She had come to the colony in 1634, and began preaching a "covenant of grace" following her mentor, John Cotton, while most of the colony's leadership, including Dudley, Winthrop, and most of the ministers, espoused a more Legalist view ("covenant of works"). This split divided the colony, since Vane and Cotton supported her. At the end of this colonial strife, called the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

, Hutchinson was banished from the colony, and a number of her followers left the colony as a consequence. She settled in Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

, where Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

, also ''persona non-grata

In diplomacy, a ' (Latin: "person not welcome", plural: ') is a status applied by a host country to foreign diplomats to remove their protection of diplomatic immunity from arrest and other types of prosecution.

Diplomacy

Under Article 9 of the ...

'' in Massachusetts over theological differences, offered her shelter. Dudley's role in the affair is unclear, but historians supportive of Hutchinson's cause argue that he was a significant force in her banishment, and that he was unhappy that the colony did not adopt a more rigid stance or ban more of her followers.

Vane was turned out of office in 1637 over the Hutchinson affair and his insistence on flying the English flag

The flag of England is the national flag of England, a constituent country of the United Kingdom. It is derived from Saint George's Cross (heraldic blazon: ''Argent, a cross gules''). The association of the red cross as an emblem of England ...

over the colony's fort; many Puritans felt that the Cross of St George

The Cross of Saint George (russian: Георгиевский крест, Georgiyevskiy krest) is a state decoration of the Russian Federation. It was initially established by Imperial Russia where it was officially known as the Decoration of ...

on the flag was a symbol of popery

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

and was thus anathema to them. Vane was replaced by Winthrop, who then served three terms. According to Winthrop, concerns over the length of his service led to Dudley's election as governor in 1640.

Although Dudley and Winthrop clashed with each other on a number of issues, they agreed on the banning of Hutchinson, and their relationship had some significant positive elements. In 1638 Dudley and Winthrop were each granted a tract of land "about six miles from Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

, northward".Jones, p. 251 Reportedly, Winthrop and Dudley went to the area together to survey the land and select their parcels. Winthrop, then governor, graciously deferred to Dudley, then deputy governor, to make the first choice of land. Dudley's land became Billerica

Billerica (, ) is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 42,119 according to the 2020 census. It takes its name from the town of Billericay in Essex, England.

History

In the early 1630s, a Praying India ...

, and Winthrop's Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

. The place where the two properties met was marked by two large stones, each carved with the owner's name; Winthrop described the spot as the "'Two Brothers Two Brothers may refer to:

Films

* ''Two Brothers'' (1929 film), a 1929 German silent film, directed by Mikhail Dubson

* ''Two Brothers'' (2004 film), a 2004 French-British film, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud

* ''The Two Brothers'' (film), a ...

', in remembrance that they were brothers by their children's marriage".

Other political activities

During Dudley's term of office in 1640, many new laws were passed. This led to the introduction the following year of theMassachusetts Body of Liberties

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties was the first legal code established in New England, compiled by Puritan minister Nathaniel Ward. The laws were established by the Massachusetts General Court in 1641. The Body of Liberties begins by establishin ...

, a document that contains guarantees that were later placed in the United States Bill of Rights

The United States Bill of Rights comprises the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. Proposed following the often bitter 1787–88 debate over the ratification of the Constitution and written to address the objections rais ...

. During this term he joined moderates, including John Winthrop, in opposing attempts by the local clergy to take a more prominent and explicit role in the colony's governance. When he was again governor in 1645 the colony threatened war against the expansionist Narragansetts

The Narragansett people are an Algonquian American Indian tribe from Rhode Island. Today, Narragansett people are enrolled in the federally recognized Narragansett Indian Tribe. They gained federal recognition in 1983.

The tribe was nearly lan ...

, who had been making war against the English-allied Mohegans

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the east ...

. This prompted the Narragansett leader Miantonomi

Miantonomoh (1600? – August 1643), also spelled Miantonomo, Miantonomah or Miantonomi, was a chief of the Narragansett people of New England Indians.

Biography

He was a nephew of the Narragansett grand sachem, Canonicus (died 1647), with whom h ...

to sign a peace agreement with the New England colonies which lasted until King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

broke out 30 years later. Dudley also presided over the acquittal of John Winthrop in a trial held that year; Winthrop had been charged with abuses of his power as a magistrate by residents of Hingham the previous year.

In 1649 Dudley was appointed once again to serve as a commissioner and president of the

In 1649 Dudley was appointed once again to serve as a commissioner and president of the New England Confederation

The United Colonies of New England, commonly known as the New England Confederation, was a confederal alliance of the New England colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Saybrook (Connecticut), and New Haven formed in May 1643. Its primary purp ...

, an umbrella organization established by most of the New England colonies to address issues of common interest; however, he was ill (and aging, at 73), and consequently unable to discharge his duties in that office. Despite the illness, Dudley was elected governor for the fourth and last time in 1650. The most notable acts during this term were the issuance of a new charter for Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

, and the judicial decision to burn ''The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption'', a book by Springfield resident William Pynchon

William Pynchon (October 11, 1590 – October 29, 1662) was an English colonist and fur trader in North America best known as the founder of Springfield, Massachusetts, USA. He was also a colonial treasurer, original patentee of the Massachu ...

that expounded on religious views heretical to the ruling Puritans. Pynchon was called upon to retract his views, but he chose to return to England instead of facing the magistrates.

During most of his years in Massachusetts, when not governor, Dudley served as either deputy governor or as one of the colony's commissioners to the New England Confederation. He also served as a magistrate in the colonial courts,Hurd, p. x and sat on committees that drafted the laws of the colony. His views were conservative, but he was not as strident in them as John Endecott

John Endecott (also spelled Endicott; before 1600 – 15 March 1664/1665), regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He serv ...

. Endecott notoriously defaced the English flag

The flag of England is the national flag of England, a constituent country of the United Kingdom. It is derived from Saint George's Cross (heraldic blazon: ''Argent, a cross gules''). The association of the red cross as an emblem of England ...

in 1632, an act for which he was censured and deprived of office for one year. Dudley sided with the moderate faction on the issue, which believed the flag's depiction of the Cross of St George had by then been reduced to a symbol of nationalism.

Nathaniel Morton

Capt. Nathaniel Morton (christened 161629 June 1685) was a Separatist settler of Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, where he served for most of his life as Plymouth's secretary under his uncle, Governor William Bradford. Morton wrote an account of ...

, an early chronicler of the Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the British America, first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the pa ...

, wrote of Dudley, "His zeal to order appeared in contriving good laws, and faithfully executing them upon criminal offenders, heretics, and underminers of true religion. He had a piercing judgment to discover the wolf, though clothed with a sheepskin."Moore, p. 292 Early Massachusetts historian James Savage wrote of Dudley that " hardness in public, and rigidity in private life, are too observable in his character". In a more modern historical view, Francis Bremer observes that Dudley was "more precise and rigid than the moderate Winthrop in his approach to the issues facing the colonists".

Founding of Harvard and Roxbury Latin

In 1637 the colony established a committee "to take order for a new college at Newtown".Jones, p. 243 The committee consisted of most of the colony's elders, including Dudley. In 1638, John Harvard, a childless colonist, bequeathed to the colony his library and half of his estate as a contribution to the college, which was consequently named in his honor. The college charter was first issued in 1642, and a second charter was issued in 1650, signed by then-Governor Thomas Dudley, who also served for many years as one of the college's overseers. Harvard University's Dudley House, now only an administrative unit located in Lehman Hall after the actual house was torn down, is named in honor of the Dudley family.Harvard Yard

Harvard Yard, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is the oldest part of the Harvard University campus, its historic center and modern crossroads. It contains most of the freshman dormitories, Harvard's most important libraries, Memorial Church, sever ...

once had a Dudley Gate bearing words written by his daughter Anne;Morison, p. 195 it was torn down in the 1940s to make way for construction of Lamont Library

Lamont Library, in the southeast corner of Harvard Yard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, houses the Harvard Library's primary undergraduate collection in humanities and social sciences. It was the first library in the United States specifically plann ...

. A fragment remains in Dudley Garden, behind Lamont Library, including a lengthy inscription in stone.

In 1643, Reverend John Eliot established a school at Roxbury. Dudley, who was then living in Roxbury, gave significant donations of both land and money to the school, which survives to this day as the Roxbury Latin School

The Roxbury Latin School is a private boys' day school that was founded in 1645 in the town of Roxbury (now a neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts) by the Rev. John Eliot under a charter received from King Charles I of England. It bills ...

.

Family and legacy

Dudley married Dorothy Yorke in 1603, and with her had five or six children. Samuel, the first, also came to the New World, and married Winthrop's daughter Mary in 1633, the first of several alliances of the Dudley-Winthrop family. He later served as the pastor inExeter, New Hampshire

Exeter is a town in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 16,049 at the 2020 census, up from 14,306 at the 2010 census. Exeter was the county seat until 1997, when county offices were moved to neighboring Brentwood. ...

. Daughter Anne married Simon Bradstreet

Simon Bradstreet (baptized March 18, 1603/4In the Julian calendar, then in use in England, the year began on March 25. To avoid confusion with dates in the Gregorian calendar, then in use in other parts of Europe, dates between January and Ma ...

, and became the first poet published in North America. Patience, Dudley's third child, married colonial militia officer Daniel Denison (colonist), Daniel Denison. The fourth child, Sarah, married Benjamin Keayne, a militia officer. This union was an unhappy one, and resulted in the first reported instance of divorce in the colony; Keayne returned to England and repudiated the marriage. Although no formal divorce proceedings are known, Sarah eventually married again, to Job Judkins, by whom she bore five children. Mercy, the last of his children with Dorothy, married minister John Woodbridge.

Dudley may have had another son, though most historians seem to think the evidence is too slim. A “Thomas Dudley” was awarded degrees from Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, in 1626 and 1630, and some historians have argued this is a son of Dudley. Also, Dudley was referred to as “Thomas Dudley Senior” on a lone occasion in 1637.

Dorothy Yorke died 27 December 1643 at 61 years of age, and was remembered by her daughter Anne in a poem:

Dudley married his second wife, the widow Katherine (Deighton) Hackburne, descendant of the noble Berkeley, Lygon and Beauchamp families, in 1644. She is also a direct descendant of eleven of the twenty-five barons who acted as sureties for John, King of England, John Lackland on the Magna Carta. They had three children, Deborah, Joseph Dudley, Joseph, and Paul. Joseph served as governor of the Dominion of New England and of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Paul (not to be confused with Joseph's son Paul Dudley (jurist), Paul, who served as provincial attorney general) was for a time the colony's register of probate.Moore, pp. 295–296

In 1636 Dudley moved from Cambridge to Ipswich, Massachusetts, Ipswich, and in 1639 moved to Roxbury. He died in Roxbury on 31 July 1653, and was buried in the Eliot Burying Ground there. Dudley, Massachusetts

Dudley is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 11,921 at the 2020 census.

History

Dudley was first settled in 1714 and was officially incorporated in 1732. The town was named for landholders Paul and Will ...

is named for his grandsons Paul and William, who were its first proprietors.

The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation owns a parcel of land in Billerica called Governor Thomas Dudley Park. The "Two Brothers" rocks are located in the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Bedford, in an area that has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Two Brothers Rocks-Dudley Road Historic District.

Dudley Square

Dudley Square in Boston's Roxbury neighborhood was named after Dudley. Proponents of an effort to rename the square noted that Dudley was "a leading politician in 1641", when the colony became the first to legally sanction slavery. Conversely, Byron Rushing, former president of the African Meeting House, Museum of African American History in Boston, stated, “I’ve really searched, and I’ve found no evidence that Dudley ever owned slaves." A non-binding advisory question was added to the 5 November 2019, municipal ballot for all Boston residents asking, "Do you support the renaming/changing of the name of Dudley Square to Nubian Square?" Election night results show that the question was defeated. Mayor of Boston Marty Walsh subsequently announced that the question had "passed in the surrounding areas" near the square, and could be considered further by the city's Public Improvement Commission. On 19 December 2019, the Public Improvement Commission unanimously approved changing the name of Dudley Square to Nubian Square. Dudley station was renamed Nubian station in June 2020.Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

"The Mystery of Thomas Dudley's Paternal Ancestors"

H. Allen Curtis

The Eagle Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dudley, Thomas 1576 births 1653 deaths Colonial governors of Massachusetts Lieutenant Governors of colonial Massachusetts Harvard University people New England Puritanism Politicians from Boston People from West Northamptonshire District American Puritans Dudley family, Thomas 16th-century English people 17th-century English people People from colonial Boston Kingdom of England emigrants to Massachusetts Bay Colony Burials in Boston People from Cambridge, Massachusetts