Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

's tenure as the

33rd president of the United States

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been

vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

for only days when he succeeded to the presidency. Truman, a

Democrat from

Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, ran for and won a full four-year term in the

1948 presidential election, in which he narrowly defeated

Republican nominee

Thomas E. Dewey and

Dixiecrat

The States' Rights Democratic Party (whose members are often called the Dixiecrats), also colloquially referred to as the Dixiecrat Party, was a short-lived segregationist, States' Rights, and old southern democratic political party in the ...

nominee

Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902 – June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Before his 49 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South ...

. Although exempted from the newly ratified

Twenty-second Amendment

The Twenty-second Amendment (Amendment XXII) to the United States Constitution limits the number of times a person can be elected to the office of President of the United States to two terms, and sets additional eligibility conditions for presi ...

was not retroactive to previous terms he had served, Truman withdrew his bid for a second full term in the

1952 presidential election because of his low popularity. He was succeeded by Republican

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

.

Truman's presidency was a turning point in foreign affairs, as the United States engaged in an internationalist foreign policy and renounced

isolationism

Isolationism is a term used to refer to a political philosophy advocating a foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality an ...

. During his first year in office, Truman approved the

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

and subsequently accepted the

surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was Hirohito surrender broadcast, announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally Japanese Instrument of Surrender, signed on 2 September 1945, End of World War II in Asia, ending ...

, which marked the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. In the

aftermath of World War II

The aftermath of World War II saw the rise of two global superpowers, the United States (U.S.) and the Soviet Union (U.S.S.R.). The aftermath of World War II was also defined by the rising threat of nuclear warfare, the creation and implementati ...

, he helped establish the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

and other post-war institutions. Relations with the Soviet Union declined after 1945, and by 1947 the two countries had entered a long period of tension and war preparation known as the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, during which a hot fighting war with Moscow was avoided. Truman broke with Roosevelt's prior vice president

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was the 33rd vice president of the United States, serving from 1941 to 1945, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He served as the 11th U.S. secretary of agriculture and the 10th U.S ...

, who called for friendship with Moscow and ran as the presidential candidate of

Progressive Party in 1948. In 1947, Truman promulgated the

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

, which called for the United States to prevent the spread of

Communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

through foreign aid to Greece and Turkey. In 1948 the Republican-controlled Congress approved the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

, a massive financial aid package designed to rebuild Western Europe. In 1949, the Truman administration designed and presided over the creation of

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

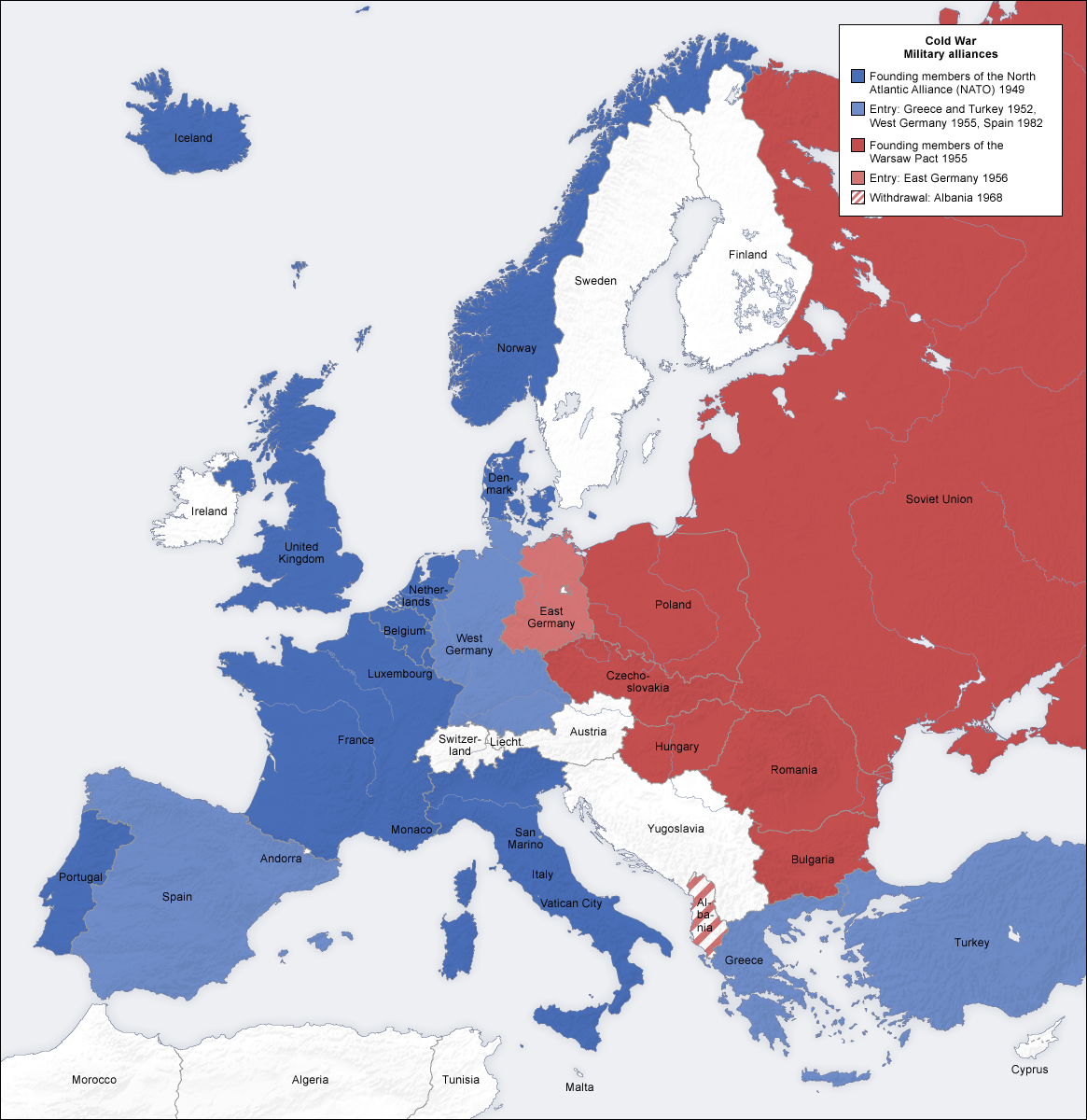

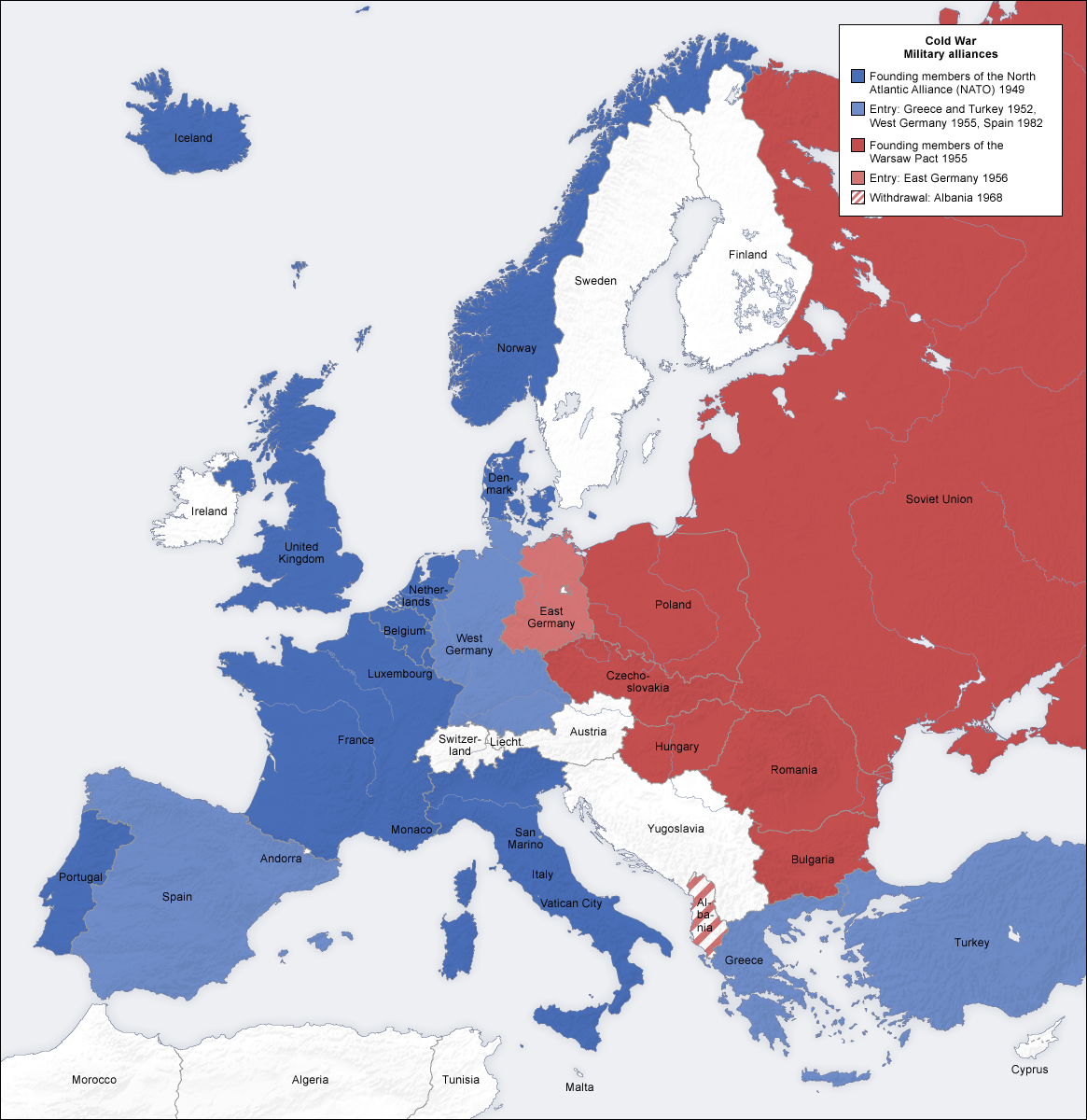

, a military alliance of Western countries designed to prevent the further westward expansion of Soviet power.

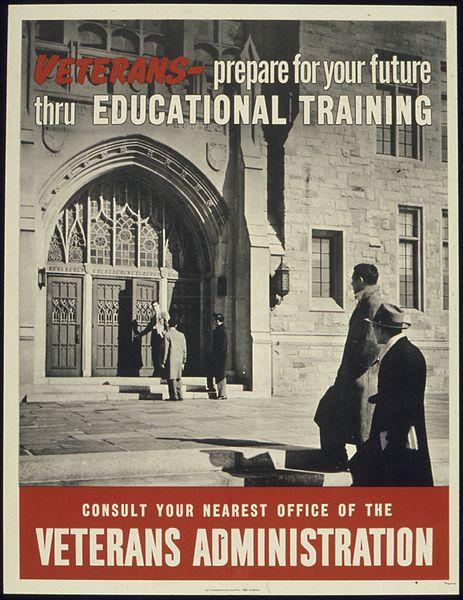

Truman proposed an ambitious domestic liberal agenda known as the

Fair Deal. However, nearly all his initiatives were blocked by the

conservative coalition

The conservative coalition, founded in 1937, was an unofficial alliance of members of the United States Congress which brought together the conservative wings of the Republican and Democratic parties to oppose President Franklin Delano Rooseve ...

of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats. Republicans took control of Congress in the 1946 elections after the

strike wave of 1945–46

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

. Truman suffered another major defeat by the conservative coalition when the 80th Congress passed the

Taft–Hartley Act

The Labor Management Relations Act, 1947, better known as the Taft–Hartley Act, is a Law of the United States, United States federal law that restricts the activities and power of trade union, labor unions. It was enacted by the 80th United S ...

into law over his veto. It reversed some of the pro-labor union legislation that was central to the New Deal. When

Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate majority le ...

, the conservative Republican senator, unexpectedly supported the

Housing Act of 1949

The American Housing Act of 1949 () was a landmark, sweeping expansion of the federal role in mortgage insurance and issuance and the construction of public housing. It was part of President of the United States, President Harry Truman's program ...

, Truman achieved one new liberal program. Truman took a strong stance on civil rights, ordering equal rights in the military to the disgust of the white politicians in the Deep South. They supported a "

Dixiecrat

The States' Rights Democratic Party (whose members are often called the Dixiecrats), also colloquially referred to as the Dixiecrat Party, was a short-lived segregationist, States' Rights, and old southern democratic political party in the ...

" third-party candidate,

Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902 – June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Before his 49 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South ...

, in 1948. Truman later pushed for the integration of the military in the 1950s. During his presidency, fears of Soviet espionage led to a

Red Scare

A Red Scare is a form of moral panic provoked by fear of the rise of left-wing ideologies in a society, especially communism and socialism. Historically, red scares have led to mass political persecution, scapegoating, and the ousting of thos ...

; Truman denounced those who made unfounded accusations of Soviet sympathies, but also purged left-wing federal employees who refused to disavow Communism.

When Communist

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

invaded

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

in 1950, Truman sent U.S. troops to prevent the fall of South Korea. After initial successes, however, the war settled into a stalemate that lasted throughout the final years of Truman's presidency. Truman left office as one of the most unpopular presidents of the twentieth century, mainly due to the Korean War and his then controversial decision to

dismiss General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

, resulting in a huge loss of support. In the 1952 presidential election, Eisenhower successfully campaigned against what he denounced as Truman's failures: "Korea, Communism and Corruption". Nonetheless, Truman retained a strong reputation among scholars, and his public reputation eventually recovered in the 1960s. In polls of historians and political scientists, Truman is generally

ranked as one of the ten greatest presidents.

Accession

President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

sought re-election in the

1944 presidential election. Roosevelt personally favored either incumbent Vice President

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was the 33rd vice president of the United States, serving from 1941 to 1945, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He served as the 11th U.S. secretary of agriculture and the 10th U.S ...

or

James F. Byrnes as his running mate. However, Wallace was unpopular among conservatives in the

Democratic Party. Byrnes, an ex-Catholic, was opposed by many liberals and Catholics. At the behest of party leaders, Roosevelt agreed to run with Truman, who was acceptable to all factions of the party, and Truman was nominated for vice president at the

1944 Democratic National Convention.

Democrats retained control of Congress and the presidency in the

1944 elections, and Truman took office as vice president in January 1945. He had no major role in the administration and was not informed of key developments, such as the atomic bomb. On April 12, 1945, Truman was urgently summoned to the White House, where he was met by

Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

, who informed him that the President was dead. Shocked, Truman asked Mrs. Roosevelt, "Is there anything I can do for you?", to which she replied: "Is there anything ''we'' can do for ''you''? For you are the one in trouble now." The day after assuming office Truman spoke to reporters: "Boys, if you ever pray, pray for me now. I don't know if you fellas ever had a load of hay fall on you, but when they told me what happened yesterday, I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me." Bipartisan favorable opinion gave the new president a honeymoon.

Administration

Truman delegated a great deal of authority to his cabinet officials, only insisting that he give the final formal approval to all decisions. After getting rid of the Roosevelt holdovers, the cabinet members were mostly old confidants. The White House was badly understaffed with no more than a dozen aides; they could barely keep up with the heavy work flow of a greatly expanded executive department. Truman acted as his own chief of staff, as well as his own liaison with Congress—a body he already knew very well. Less important matters he delegated to his Special Counsels,

Samuel Rosenman in 1945–46,

Clark Clifford in 1946 to 1950 and

Charles S. Murphy in 1950 to 1953. He was not well prepared to deal with the press. Filled with latent anger about all the setbacks in his career, he bitterly mistrusted the journalists, seeing them as enemies laying in wait for his next careless miscue. Truman was a very hard worker, often to the point of exhaustion, which left him testy and on the verge of appearing unpresidential. He discussed major issue in depth with cabinet and other advisors, such as the atom bomb, the Truman Plan, the Korean war, or the dismissal of General MacArthur. He mastered the details of the federal budget as well as anyone. Truman's myopia made it hard to read a typescript, and he was poor at prepared addresses. However, his visible anger made him an effective stump speaker, denouncing his enemies as his supporters hollered back at him, “Give Em Hell, Harry!”

At first Truman asked all the members of Roosevelt's cabinet to remain in place for the time being, but by the end of 1946 only one Roosevelt appointee, Secretary of the Navy

James Forrestal

James Vincent Forrestal (February 15, 1892 – May 22, 1949) was the last Cabinet (government), cabinet-level United States Secretary of the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense.

Forrestal came from a very strict middle-cla ...

, remained.

Fred M. Vinson

Frederick Moore Vinson (January 22, 1890 – September 8, 1953) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 13th chief justice of the United States from 1946 until his death in 1953. Vinson was one of the few Americans to have ser ...

succeeded Treasury Secretary

Henry Morgenthau Jr. in July 1945. Truman appointed Vinson to the Supreme Court in 1946 and

John Wesley Snyder was named as the Treasury Secretary. Truman quickly replaced Secretary of State

Edward Stettinius Jr. with James F. Byrnes, an old friend from Senate days. However Byrnes soon lost Truman's trust with his conciliatory policy towards Moscow in late 1945, and he was replaced by former General

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

in January 1947. Undersecretary of State

Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

was the main force in foreign affairs along with a group of advisers known as the "

Wise Men," Marshall emerged as the face of Truman's foreign policy.

In 1947, Forrestal became the first

Secretary of Defense, overseeing all branches of the

United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

. A mental breakdown sent him into retirement in 1949, and he was replaced successively by

Louis A. Johnson, Marshall, and finally

Robert A. Lovett

Robert Abercrombie Lovett (September 14, 1895May 7, 1986) was an American politician who served as the fourth United States Secretary of Defense, having been promoted to this position from Deputy Secretary of Defense. He served in the cabinet of ...

. Acheson was Secretary of State 1949–1953. Truman often appointed longtime personal friends, sometimes to positions well beyond their competence. Such friends included Vinson, Snyder, and military aide

Harry H. Vaughan. Outside of the cabinet,

Clark Clifford and

John R. Steelman were staffers who handled lesser matters while Truman acted as his own chief off staff on big issues.

Vice presidency

The office of vice president remained vacant during Truman's first ( partial) term, as the Constitution then had no provision for filling a vacancy prior to the 1967 ratification of the

Twenty-fifth Amendment. Until the passage of the

Presidential Succession Act

The United States Presidential Succession Act is a federal statute establishing the presidential line of succession. Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the United States Constitution authorizes Congress to enact such a statute:

Congress ha ...

of 1947, the Secretary of State was next in the

presidential line of succession. After the passage of the act in July 1947, the

Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

became the next-in-line. During different points of Truman's first term, Secretary of State Stettinius, Secretary of State Byrnes, Secretary of State Marshall, Speaker

Joseph Martin, and Speaker

Sam Rayburn

Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn (January 6, 1882 – November 16, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 43rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a three-time House speaker, former House majority leader, two-time ...

would have succeeded to the presidency if Truman left office.

Alben Barkley

Alben William Barkley (; November 24, 1877 – April 30, 1956) was the 35th vice president of the United States serving from 1949 to 1953 under President Harry S. Truman. In 1905, he was elected to local offices and in 1912 as a U.S. rep ...

served as Truman's running mate in the 1948 election, and became vice president during Truman's second term. Truman included him in Cabinet deliberations.

Judicial appointments

Truman made four appointments to the

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

. After the retirement of

Owen Roberts in 1945, Truman appointed Republican Senator

Harold Hitz Burton of Ohio to the Supreme Court. Roberts was the lone remaining justice on the Supreme Court who had not been appointed or elevated to the position of

chief justice by Roosevelt, and Truman believed it was important to nominate a Republican to succeed Roberts. Chief Justice

Harlan F. Stone died in 1946, and Truman appointed Secretary of the Treasury Fred M. Vinson as Stone's successor. Two vacancies arose in 1949 due to deaths of

Frank Murphy and

Wiley Blount Rutledge

Wiley Blount Rutledge Jr. (July 20, 1894 – September 10, 1949) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1943 to 1949. The ninth and final justice appointed by President Franklin ...

. Truman appointed Attorney General

Tom C. Clark

Thomas Campbell Clark (September 23, 1899June 13, 1977) was an American lawyer who served as the 59th United States Attorney General, United States attorney general from 1945 to 1949 and as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United St ...

to succeed Murphy and federal appellate judge

Sherman Minton

Sherman "Shay" Minton (October 20, 1890 – April 9, 1965) was an American politician and jurist who served as a U.S. senator from Indiana and later became an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States; he was a member of the ...

to succeed Rutledge. Vinson served for just seven years before his death in 1953, while Minton resigned from the Supreme Court in 1956. Burton served until 1958, often joining the conservative bloc led by

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

. Clark served until 1967, emerging as an important swing vote on the

Vinson Court

The Vinson Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1946 to 1953, when Fred M. Vinson served as Chief Justice of the United States. Vinson succeeded Harlan F. Stone as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and Vinson served ...

and the

Warren Court

The Warren Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1953 to 1969 when Earl Warren served as the chief justice. The Warren Court is often considered the most liberal court in U.S. history.

The Warren Cou ...

. In addition to his Supreme Court appointments, Truman also appointed 27 judges to the

courts of appeals and 101 judges to

federal district courts.

End of World War II

By April 1945, the

Allied Powers were close to defeating

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, but

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

remained a formidable adversary in the

Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

. As vice president, Truman had been uninformed about major initiatives relating to the war, including the top-secret

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, which was about to test the world's first atomic bomb.

[Barton J. Bernstein, "Roosevelt, Truman, and the atomic bomb, 1941–1945: a reinterpretation." ''Political Science Quarterly'' 90.1 (1975): 23–69.] Although Truman was told briefly on the afternoon of April 12 that the Allies had a new, highly destructive weapon, it was not until April 25 that Secretary of War

Henry Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and Demo ...

told him the details of the atomic bomb, which was almost ready. Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, ending the war in Europe. Truman's attention turned to the Pacific, where he hoped to end the war as quickly, and with as little expense in lives or government funds, as possible.

With the end of the war drawing near, Truman flew to Berlin for the

Potsdam Conference, to meet with Soviet leader

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

and British leader

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

regarding the

post-war order. Several major decisions were made at the Potsdam Conference: Germany would be divided into four occupation zones (among the three powers and

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

), Germany's border was to be shifted west to the

Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

, a Soviet-backed

group

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic iden ...

was recognized as the legitimate government of Poland, and

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

was to be partitioned at the 16th parallel. The Soviet Union also agreed to

launch an invasion of Japanese-held

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

. While at the Potsdam Conference, Truman was informed that the

Trinity test

Trinity was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. MWT (11:29:21 GMT) on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was of an implosion-design plutonium bomb, or "gadg ...

of the first atomic bomb on July 16 had been successful. He hinted to Stalin that the U.S. was about to use a new kind of weapon against the Japanese. Though this was the first time the Soviets had been officially given information about the atomic bomb, Stalin was already aware of the bomb project, having learned about it through

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

long before Truman did.

In August 1945, the Japanese government ignored surrender demands as specified in the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, ...

. With the support of most of his aides, Truman approved the schedule of the military's plans to

drop atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

and

Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

. Hiroshima was bombed on August 6, and Nagasaki three days later, leaving approximately 135,000 dead; another 130,000 would die from radiation sickness and other bomb-related illnesses in the following five years. After the Soviet Union

invaded Manchuria, Japan

agreed to surrender on August 10 on the sole condition that Emperor

Hirohito

, Posthumous name, posthumously honored as , was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigni ...

would not be forced to abdicate; after some internal debate, the Truman administration accepted these terms of surrender.

The decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

provoked long-running debates. Supporters of the bombings argue that, given the tenacious Japanese defense of the outlying islands, the bombings saved hundreds of thousands of lives that would have been lost

invading mainland Japan. After leaving office, Truman told a journalist that the atomic bombing "was done to save 125,000 youngsters on the American side and 125,000 on the Japanese side from getting killed and that is what it did. It probably also saved a half million youngsters on both sides from being maimed for life." Truman was also motivated by a desire to end the war before the Soviet Union could invade Japanese-held territories and set up Communist governments. Critics, such as Allied commander and Truman's successor Dwight D. Eisenhower, have argued that the use of nuclear weapons was unnecessary, given that conventional tactics such as firebombing and blockade might induce Japan's surrender without the need for such weapons.

Foreign affairs

Truman's chief advisors came from the State Department, especially

Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

. The main issues of the

United States foreign policy during include:

* Final stages of World War II included the problem of defeating Japan with minimal American casualties. Truman asked Moscow to invade from the north, and decided to drop two atomic bombs.

* Post-war Reconstruction: Following the end of World War II, Truman faced the task of rebuilding Europe and Japan. He implemented the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

to provide economic aid to Europe and Washington supervised the reconstruction of Japan.

* Formation of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

: Truman played a key role in the formation of the United Nations, which was established in 1945 to promote international cooperation and prevent another world war. Because of the Soviet veto, it was ineffective in most major disputes.

*

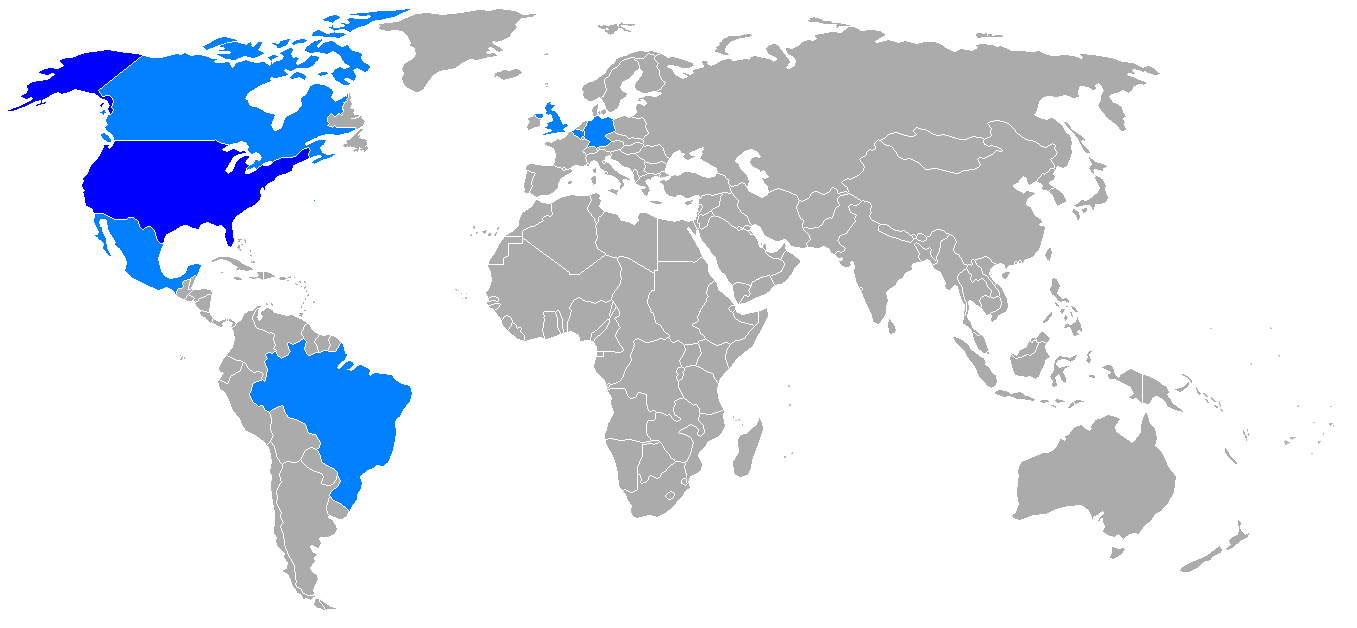

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

: Truman led the nation into the Cold War in 1947, a period of heightened tensions and rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. Truman helped form the

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

military alliance. He implemented the policy of

containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

, which aimed to stop the spread of communism and limit Soviet influence around the world.

*

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

: In 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea, leading to a bloody conflict that lasted until 1953. Truman authorized U.S. military intervention in the conflict, which led to a protracted and costly war. He rejected the advice of General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

, and fired him in 1951.

*

Nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

: Truman made the decision to build the hydrogen bomb. He oversaw the development of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and the start of the nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union, which had far-reaching implications for U.S. foreign policy.

Postwar international order

United Nations

In his last years in office Roosevelt had promoted several major initiatives to reshape the postwar politics and economy, and avoid the mistakes of 1919. Chief among those organizations was the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, an intergovernmental organization similar to the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

that was designed to help ensure international cooperation. When Truman took office, delegates were about to meet at the

United Nations Conference on International Organization

The United Nations Conference on International Organization (UNCIO), commonly known as the San Francisco Conference, was a convention of delegates from 50 Allies of World War II, Allied nations that took place from 25 April 1945 to 26 June 194 ...

in San Francisco. As a

Wilsonian

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of United States President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending Wor ...

internationalist, Truman strongly supported the creation of the United Nations, and he signed the

United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the United Nations System, UN system, including its United Nations System#Six ...

at the San Francisco Conference. Truman did not repeat

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's partisan attempt to ratify the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

in 1919. Instead he cooperated closely with Senator

Arthur H. Vandenberg and other Republican leaders to ensure ratification. Cooperation with Vandenberg, a leading figure on the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for authorizing and overseeing foreign a ...

, proved crucial for Truman's foreign policy, especially after Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1946 elections. Construction of the

United Nations headquarters

The headquarters of the United Nations (UN) is on of grounds in the Turtle Bay, Manhattan, Turtle Bay neighborhood of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It borders First Avenue (Manhattan), First Avenue to the west, 42nd Street (Manhattan), 42nd ...

in New York City was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and completed in 1952.

Trade and low tariffs

In 1934, Congress had passed the

Reciprocal Tariff Act

The Reciprocal Tariff Act (enacted June 12, 1934, ch. 474, , ) provided for the negotiation of tariff agreements between the United States and separate nations, particularly Latin American countries. The Act served as an institutional reform int ...

, giving the president an unprecedented amount of authority in setting

tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

rates. The act allowed for the creation of reciprocal agreements in which the U.S. and other countries mutually agreed to lower tariff rates.

Despite significant opposition from those who favored higher tariffs, Truman was able to win legislative extension of the reciprocity program, and his administration reached numerous bilateral agreements that lowered trade barriers. The Truman administration also sought to further lower global tariff rates by engaging in multilateral trade negotiations, and the State Department proposed the establishment of the

International Trade Organization

The International Trade Organization (ITO) was the proposed name for an international institution for the regulation of trade.

Led by the United States in collaboration with allies, the effort to form the organization from 1945 to 1948, with the ...

(ITO). The ITO was designed to have broad powers to regulate trade among member countries, and its charter was approved by the United Nations in 1948. However, the ITO's broad powers engendered opposition in Congress, and Truman declined to send the charter to the Senate for ratification. In the course of creating the ITO, the U.S. and 22 other countries signed the

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a legal agreement between many countries, whose overall purpose was to promote international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers such as tariffs or quotas. According to its p ...

(GATT), a set of principles governing trade policy. Under the terms of the agreement, each country agreed to reduce overall tariff rates and to treat each co-signatory as a "

most favoured nation

In international economic relations and international politics, most favoured nation (MFN) is a status or level of treatment accorded by one state to another in international trade. The term means the country which is the recipient of this treatme ...

," meaning that no non-signatory country could benefit from more advantageous tariff rates. Due to a combination of the Reciprocal Tariff Act, the GATT, and inflation, U.S. tariff rates fell dramatically between the passage of the

Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act in 1930 and the end of the Truman administration in 1953.

European refugees

World War II left millions of refugees displaced in Europe, especially former prisoners and forced laborers in Germany. Truman took a leadership role in meeting the challenge. He backed the new

International Refugee Organization (IRO), a temporary international organization that helped resettle refugees. The United States also funded temporary camps and admitted large numbers of refugees as permanent residents. Truman obtained ample funding from Congress for the

Displaced Persons Act of 1948, which allowed many of the

displaced people of World War II to immigrate into the United States. Of the approximately one million people resettled by the IRO, more than 400,000 settled in the United States. The most contentious issue facing the IRO was the resettlement of European Jews, many of whom, with the support of Truman, were allowed to immigrate to British-controlled

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

. The administration also helped create a new category of refugee, the "escapee," at the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The American Escapee Program began in 1952 to help the flight and relocation of political refugees from communism in Eastern Europe. The motivation for the refugee and escapee programs was twofold: humanitarianism, and use as a political weapon against inhumane communism. Truman also set up a Presidential Displaced Person Commission, which people such as Harry N. Rosenfield and Walter Bierlinger served on.

Atomic energy and nuclear weapons

In March 1946, at an optimistic moment for postwar cooperation, the administration released the

Acheson-Lilienthal Report, which proposed that all nations voluntarily abstain from constructing nuclear weapons. As part of the proposal, the U.S. would dismantle its nuclear program once all other countries agreed not to develop or otherwise acquire nuclear weapons. Fearing that Congress would reject the proposal, Truman turned to the well-connected

Bernard Baruch

Bernard Mannes Baruch (August 19, 1870 – June 20, 1965) was an American financier and statesman.

After amassing a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange, he impressed President Woodrow Wilson by managing the nation's economic mobilization in W ...

to represent the U.S. position to the United Nations. The

Baruch Plan

The Baruch Plan was a proposal put forward by the United States government on 14 June 1946 to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC) during its first meeting. Bernard Baruch wrote the bulk of the proposal, based on the March 1946 Ac ...

, largely based on the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, was not adopted due to opposition from Congress and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union would

develop its own nuclear arsenal, testing a nuclear weapon for the first time in August 1949.

The

United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

, directed by

David E. Lilienthal until 1950, was in charge of designing and building nuclear weapons under a policy of full civilian control. The U.S. had only 9 atomic bombs in 1946, but the stockpile grew to 650 by 1951. Lilienthal wanted to give high priority to peaceful uses for

nuclear technology

Nuclear technology is technology that involves the nuclear reactions of atomic nucleus, atomic nuclei. Among the notable nuclear technologies are nuclear reactors, nuclear medicine and nuclear weapons. It is also used, among other things, in s ...

, especially

nuclear power plant

A nuclear power plant (NPP), also known as a nuclear power station (NPS), nuclear generating station (NGS) or atomic power station (APS) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power st ...

s, but coal was cheap and the power industry was largely uninterested in building

nuclear power plant

A nuclear power plant (NPP), also known as a nuclear power station (NPS), nuclear generating station (NGS) or atomic power station (APS) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power st ...

s during the Truman administration. Construction of the first nuclear plant would not begin until 1954.

The Soviet Union's successful test of an atomic bomb in 1949 triggered an intense debate over whether the United States should proceed with development of the much more powerful

hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

.

There was opposition to the idea from many in the scientific community and from some government officials, but Truman believed that the Soviet Union would likely develop the weapon itself and was unwilling to allow the Soviets to have such an advantage. Thus in early 1950, Truman made the decision to go forward with the H-bomb.

[Paul Y. Hammond, ''NSC-68: Prologue to Rearmament'', pp. 290–292, in Warner R. Schilling, Paul Y. Hammond, and Glenn H. Snyder, ''Strategy, Politics, and Defense Budgets'' (Columbia University Press, 1962).] The

first test of thermonuclear weaponry was conducted by the United States in 1952; the Soviet Union would perform

its own thermonuclear test in August 1953.

Beginning of the Cold War, 1945–1949

Escalating tensions, 1945–1946

The Second World War dramatically upended the international system, as formerly-powerful nations like Germany, France, Japan, and even the USSR and Britain had been devastated. At the end of the war, only the United States and the Soviet Union had the ability to exercise influence, and a bipolar international power structure replaced the multipolar structure of the

Interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

. On taking office, Truman privately viewed the Soviet Union as a "police government pure and simple," but he was initially reluctant to take a hard-line towards it, as he hoped to work with Stalin the

aftermath of Second World War. Truman's suspicions deepened as the Soviets consolidated their

control in Eastern Europe throughout 1945, and the February 1946 announcement of the Soviet

five-year plan further strained relations as it called for the continuing build-up of the Soviet military. At the December 1945

Moscow Conference, Secretary of State Byrnes agreed to recognize the pro-Soviet governments in the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, while the Soviet leadership accepted U.S. leadership in the

occupation of Japan

Japan was occupied and administered by the Allies of World War II from the surrender of the Empire of Japan on September 2, 1945, at the war's end until the Treaty of San Francisco took effect on April 28, 1952. The occupation, led by the ...

. U.S. concessions at the conference angered other members of the Truman administration, including Truman himself. By the beginning of 1946, it had become clear to Truman that Britain and the United States would have little influence in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe.

Henry Wallace, Eleanor Roosevelt, and many other prominent New Dealers continued to hope for cooperative relations with the Soviet Union. Some liberals, like

Reinhold Niebuhr

Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr (June 21, 1892 – June 1, 1971) was an American Reformed theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics and public affairs, and professor at Union Theological Seminary for more than 30 years. Niebuhr was one of Ameri ...

, distrusted the Soviet Union but believed that the United States should not try to counter Soviet influence in Eastern Europe, which the Soviets saw as their "strategic security belt." Partly because of this sentiment, Truman was reluctant to fully break with the Soviet Union in early 1946, but he took an increasingly hard line towards the Soviet Union throughout the year. He privately approved of Winston Churchill's March 1946 "

Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

" speech, which urged the United States to take the lead of an anti-Soviet alliance, though he did not publicly endorse it.

Throughout 1946, tensions arose between the United States and the Soviet Union in places like

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, which the Soviets had partly occupied during World War II. Pressure from the U.S. and the United Nations finally forced the withdrawal of Soviet soldiers.

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

also emerged as a point of contention, as the Soviet Union demanded joint control over the

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

and the

Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

, key straits that controlled movement between the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

and the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

. The U.S. forcefully opposed this proposed alteration to the 1936

Montreux Convention, which had granted Turkey sole control over the straits, and Truman dispatched a fleet to the Eastern Mediterranean to show his administration's commitment to the region. Moscow and Washington also argued over Germany, which had been divided into

four occupation zones. In the September 1946

Stuttgart speech, Secretary of State Byrnes announced that the United States would no longer seek reparations from Germany and would support the establishment of a democratic state. The United States, France, and Britain agreed to combine their occupation zones, eventually forming

West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

. In East Asia, Truman denied the Soviet request to reunify

Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

, and refused to allow the Soviets (or any other country) a role in the post-war occupation of Japan.

By September 1946, Truman was convinced that the Soviet Union sought world domination and that cooperation was futile. He adopted a policy of

containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

, based on a

1946 cable by diplomat

George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

. Containment, a policy of preventing the further expansion of Soviet influence, represented a middle-ground position between friendly

detente (as represented by Wallace), and aggressive

rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing a change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, ...

to regain territory already lost to Communism, as would be adopted in 1981 by

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

. Kennan's doctrine was based on the notion that the Soviet Union was led by an uncompromising totalitarian regime, and that the Soviets were primarily responsible for escalating tensions. Wallace, who had been appointed Secretary of Commerce after the 1944 election, resigned from the cabinet in September 1946 due to Truman's hardening stance towards the Soviet Union.

Truman Doctrine

In the first major step in implementing containment, Truman extended money to

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and Turkey to prevent the spread of Soviet-aligned governments. Prior to 1947, the U.S. had largely ignored Greece, which had an anti-communist government, because it was under British influence. Since 1944, the British had assisted the Greek government against a left-wing insurgency, but in early 1947 the British informed the United States that they could no longer afford to intervene in Greece. At the urging of Acheson, who warned that the fall of Greece could lead to the expansion of Soviet influence throughout Europe, Truman requested that Congress grant an unprecedented $400 million aid package to Greece and Turkey. In a March 1947 speech before a joint session of Congress, Truman articulated the

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

, which called for the United States to support "free people who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures." Overcoming those who opposed U.S. involvement in Greek affairs, as well those who feared that the aid would weaken post-war cooperation, Truman won bipartisan approval of the aid package. The congressional vote represented a permanent break with the

non-interventionism

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is commonly understood as "a foreign policy of political or military non-involvement in foreign relations or in other countries' internal affairs". This is based on the grounds that a state should not inter ...

that had characterized U.S. foreign policy prior to World War II.

The United States supported the government against the communists in the

Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War () took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communism, Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels decl ...

, but did not send any military force. The insurgency was defeated in 1949. Stalin and

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

n leader

Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslavia, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 unti ...

both provided aid to the insurgents, but a dispute over the aid led to the start of

a split in the Communist bloc. American military and economic aid to Turkey also proved effective, and Turkey avoided a civil war. The Truman administration also provided aid to the Italian government in advance of the

1948 general election. The aid package, combined with a covert CIA operation, anti-Communist mobilization by the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, and pressure from prominent Italian-Americans, helped to ensure a Communist defeat in the election. The initiatives of the Truman Doctrine solidified the post-war division between the United States and the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union responded by tightening its control over Eastern Europe. Countries aligned with the Soviet Union became known as the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

, while the U.S. and its allies became known as the

Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Capitalist Bloc, the Freedom Bloc, the Free Bloc, and the American Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War (1947–1991). While ...

.

Military reorganization and budgets

Learning from wartime organizational problems, the Truman administration reorganized the military and intelligence establishment to provide for more centralized control and reduce rivalries. The

National Security Act of 1947

The National Security Act of 1947 (Act of Congress, Pub.L.]80-253 61 United States Statutes at Large, Stat.]495 enacted July 26, 1947) was a law enacting major restructuring of the Federal government of the United States, United States governmen ...

combined and reorganized all military forces by merging the

United States Department of War, Department of War and the

Department of the Navy into the

National Military Establishment

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD, or DOD) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government charged with coordinating and supervising the six U.S. armed services: the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, Space Force, t ...

(which was later renamed as the

Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD, or DOD) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government charged with coordinating and supervising the six U.S. armed services: the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, Space Force, ...

). The law also created the

U.S. Air Force, the

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

(CIA), and the

National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

(NSC). The CIA and the NSC were designed to be non-military, advisory bodies that would increase U.S. preparation against foreign threats without assuming the domestic functions of the

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

. The National Security Act institutionalized the

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

, which had been established on a temporary basis during World War II. The Joint Chiefs of Staff took charge of all military action, and the Secretary of Defense became the chief presidential adviser on military matter. In 1952, Truman secretly consolidated and empowered the cryptologic elements of the United States by creating the

National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is an intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the director of national intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collection, and proces ...

(NSA). Truman and Marshall also sought to require one year of military service for all young men, but this proposal failed as it never won more than modest support among members of Congress.

Truman had hoped that the National Security Act would minimize interservice rivalries, but each branch retained considerable autonomy and battles over the military budgets and other issues continued. In 1949, Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson announced that he would cancel a so-called "

supercarrier," which many in the navy saw as an important part of the service's future. The cancellation sparked a crisis known as the "

Revolt of the Admirals", when a number of retired and active-duty admirals publicly disagreed with the Truman administration's emphasis on less expensive

strategic atomic bombs delivered by the air force. During congressional hearings, public opinion shifted strongly against the navy, which ultimately kept control of marine aviation but lost control over strategic bombing. Military budgets following the hearings prioritized the development of air force heavy bomber designs, and the United States accumulated a combat ready force of over 1,000 long-range strategic bombers capable of supporting nuclear mission scenarios.

Following the end of World War II, Truman gave a low priority to defense budgets—he was interested in curtailing military expenditures and had priorities he wanted to address with domestic spending. From the beginning, he assumed that the American monopoly on the atomic bomb was adequate protection against any and all external threats. Military spending plunged from 39 percent of GNP in 1945 to only 5 percent in 1948, but defense expenditures overall were still eight times higher in constant dollars than they had been before the war.

[Warner R. Schilling, ''The Politics of National Defense: Fiscal 1950'', pp. 29–30, in Warner R. Schilling, Paul Y. Hammond, and Glenn H. Snyder, ''Strategy, Politics, and Defense Budgets'' (Columbia University Press, 1962).] The number of military personnel fell from just over 3 million in 1946 to approximately 1.6 million in 1947, although again the number of military personnel was still nearly five times larger than that of U.S. military in 1939. These jumps were considerably larger than had taken place before and after the

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

or before and after

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, indicating that something fundamental had changed regarding American defense posture.

Paired with the aforementioned decision to go ahead with the H-bomb, Truman ordered a review of U.S. military policies as they related to foreign policy planning.

The National Security Council drafted

NSC 68, which called for a major expansion of the U.S. defense budget, increased aid to U.S. allies, and a more aggressive posture in the Cold War. Despite increasing Cold War tensions, Truman dismissed the document, as he was unwilling to commit to higher defense spending. The

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

convinced Truman of the necessity for higher defense spending, and such spending would soar between 1949 and 1953.

Marshall Plan

The United States had terminated the war-time

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (),3,000 Hurricanes and >4,000 other aircraft)

* 28 naval vessels:

** 1 Battleship. (HMS Royal Sovereign (05), HMS Royal Sovereign)

* ...

program in August 1945, but it continue a program of loans to Britain. Furthermore, the U.S. sent massive shipments of food to Europe in the years immediately following the end of the war. With the goal of stemming the spread of Communism and increasing trade between the U.S. and Europe, the Truman administration devised the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

, which sought to rejuvenate the devastated economies of Western Europe. To fund the Marshall Plan, Truman asked Congress to approve an unprecedented, multi-year, $25 billion appropriation.

Congress, under the control of conservative Republicans, agreed to fund the program for multiple reasons. The conservative isolationist wing of the Republican Party, led by Senator

Kenneth S. Wherry, argued that the Marshall Plan would be "a wasteful 'operation rat-hole'". Wherry held that it made no sense to oppose communism by supporting the socialist governments in Western Europe and that American goods would reach Russia and increase its war potential. Wherry was outmaneuvered by the emerging internationalist wing in the Republican Party, led by Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg. With support from Republican Senator

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (July 5, 1902 – February 27, 1985) was an American diplomat and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate and served as United States Ambassador to the United Nations in the administration of Pre ...

, Vandenberg admitted there was no certainty that the plan would succeed, but said it would halt economic chaos, sustain Western civilization, and stop further Soviet expansion. Both houses of Congress approved of the initial appropriation, known as the Foreign Assistance Act, by large majorities, and Truman signed the act into law in April 1948. Congress would eventually allocate $12.4 billion in aid over the four years of the plan.

In addition to aid, the Marshall Plan also focused on efficiency along the lines of American industry and removing tariffs and trade barriers. Though the United States allowed each recipient to develop its own plan for the aid, it set several rules and guidelines on the use of the funding. Governments were required to exclude Communists, socialist policies were discouraged, and balanced budgets were favored. Additionally, the United States conditioned aid to the French and British on their acceptance of the reindustrialization of Germany and support for

European integration

European integration is the process of political, legal, social, regional and economic integration of states wholly or partially in Europe, or nearby. European integration has primarily but not exclusively come about through the European Union ...

. To avoid exacerbating tensions, the U.S. invited the Soviet Union to become a recipient in the program, but set terms that Stalin was likely to reject. The Soviet Union refused to consider joining the program and vetoed participation by its own satellites. The Soviets set up their own program for aid, the

Molotov Plan

The Molotov Plan was the system created by the Soviet Union in order to provide aid to rebuild the countries in Eastern Europe that were politically and economically aligned to the Soviet Union. It was called the "Brother Plan" in the Soviet Unio ...

, and the competing plans resulted in reduced trade between the Eastern bloc and the Western bloc.

The Marshall Plan helped European economies recover in the late 1940s and early 1950s. By 1952, industrial productivity had increased by 35 percent compared to 1938 levels. The Marshall Plan also provided critical psychological reassurance to many Europeans, restoring optimism to a war-torn continent. Though European countries did not adopt American economic structures and ideas to the degree hoped for by some Americans, they remained firmly rooted in

mixed economic systems. The European integration process led to the creation of the

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

, which eventually formed the basis of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

.

Berlin airlift

In reaction to Western moves aimed at reindustrializing their German occupation zones, Stalin ordered a blockade of the Western-held sectors of

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, which was deep in the Soviet occupation zone. Stalin hoped to prevent the creation of a western German state aligned with the U.S., or, failing that, to consolidate control over eastern Germany. After the blockade began on June 24, 1948, the commander of the American occupation zone in Germany, General

Lucius D. Clay, proposed sending a large armored column across the Soviet zone to

West Berlin

West Berlin ( or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin from 1948 until 1990, during the Cold War. Although West Berlin lacked any sovereignty and was under military occupation until German reunification in 1 ...

with instructions to defend itself if it were stopped or attacked. Truman believed this would entail an unacceptable risk of war, and instead approved

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union from 1922 to 1940 and ...

's plan to supply the blockaded city by air. On June 25, the Allies initiated the

Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, roa ...

, a campaign that delivered food and other supplies, such as coal, using military aircraft on a massive scale. Nothing like it had ever been attempted before, and no single nation had the capability, either logistically or materially, to accomplish it. The airlift worked, and ground access was again granted on May 11, 1949. The Berlin Airlift was one of Truman's great foreign policy successes, and it significantly aided his election campaign in 1948.

NATO

Rising tensions with the Soviets, along with the Soviet veto of numerous United Nations Resolutions, convinced Truman, Senator Vandenberg, and other American leaders of the necessity of creating a defensive alliance devoted to collective security. In 1949, the United States, Canada, and several European countries signed the

North Atlantic Treaty

The North Atlantic Treaty, also known as the Washington Treaty, forms the legal basis of, and is implemented by, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The treaty was signed in Washington, D.C., on 4 April 1949.

Background

The treat ...

, creating a trans-Atlantic military alliance and committing the United States to its first permanent alliance since the

1778 Treaty of Alliance with

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...