Thornton Wilder on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

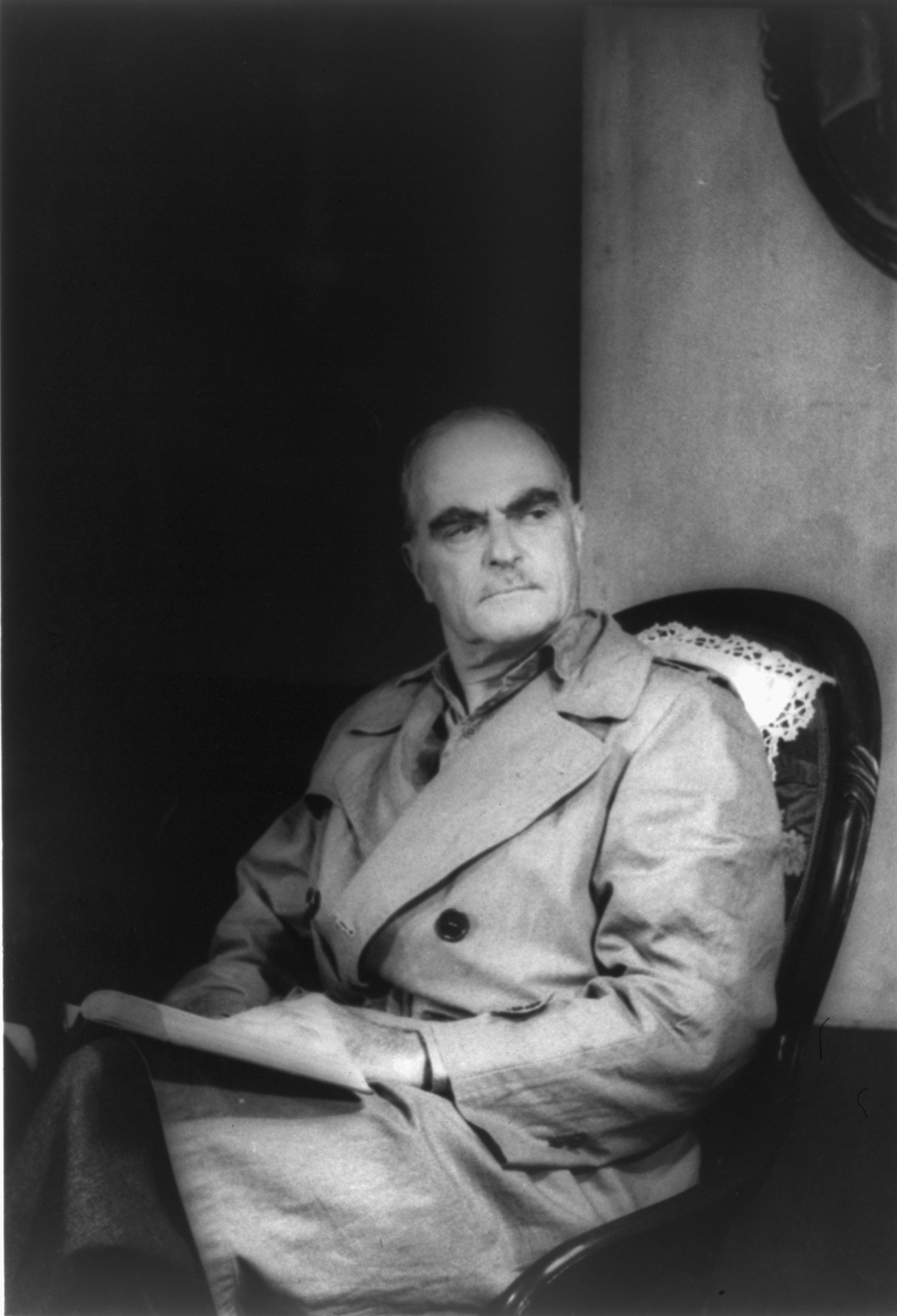

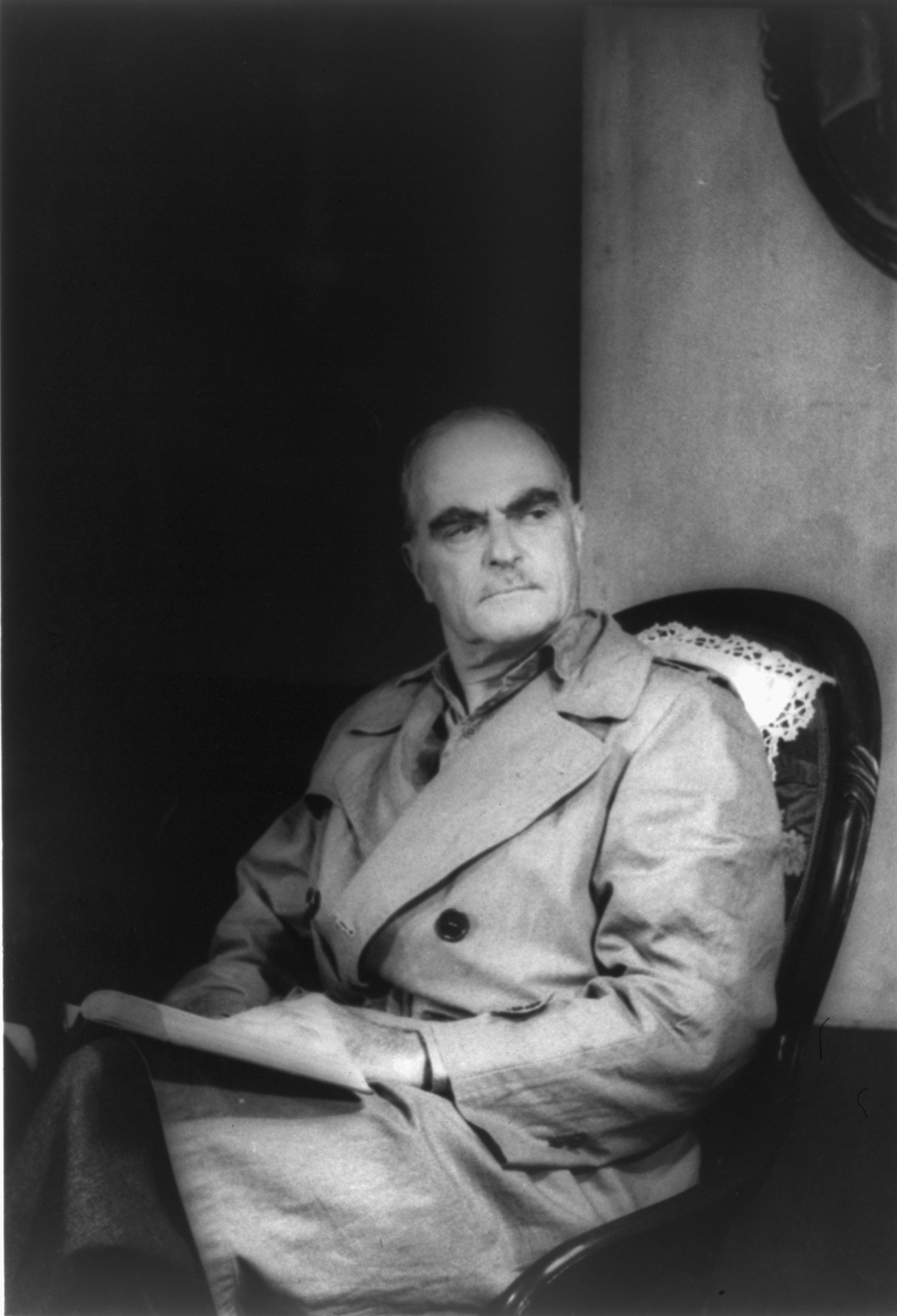

Thornton Niven Wilder (April 17, 1897 – December 7, 1975) was an American playwright and novelist. He won three Pulitzer Prizes — for the novel ''

Wilder was born in

Wilder was born in

Wilder began writing plays while at the Thacher School in Ojai, California, where he did not fit in and was teased by classmates as overly

Wilder began writing plays while at the Thacher School in Ojai, California, where he did not fit in and was teased by classmates as overly

''The Cabala''

was published in 1926. In 1927, '' Wilder wrote '' Our Town'', a popular play (and later film) set in fictional Grover's Corners, New Hampshire. It was inspired in part by Dante's ''Purgatorio'' and in part by his friend

Wilder wrote '' Our Town'', a popular play (and later film) set in fictional Grover's Corners, New Hampshire. It was inspired in part by Dante's ''Purgatorio'' and in part by his friend  In 1938, Max Reinhardt directed a Broadway production of '' The Merchant of Yonkers'', which Wilder had adapted from

In 1938, Max Reinhardt directed a Broadway production of '' The Merchant of Yonkers'', which Wilder had adapted from  In 1954, Tyrone Guthrie encouraged Wilder to rework ''The Merchant of Yonkers'' into '' The Matchmaker''. This time the play opened in 1955 and enjoyed a healthy Broadway run of 486 performances with Ruth Gordon in the title role, winning a

In 1954, Tyrone Guthrie encouraged Wilder to rework ''The Merchant of Yonkers'' into '' The Matchmaker''. This time the play opened in 1955 and enjoyed a healthy Broadway run of 486 performances with Ruth Gordon in the title role, winning a

''Past winners & finalists by category''. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved March 28, 2012. * '' The Merchant of Yonkers'' (1938) * '' The Skin of Our Teeth'' (1942)—won the Pulitzer Prize * '' The Matchmaker'' (1954)—revised from ''The Merchant of Yonkers'' * ''The Alcestiad: Or, a Life in the Sun'' (1955) * ''Childhood'' (1960) * ''Infancy'' (1960) * ''Plays for Bleecker Street'' (1962) * ''The Collected Short Plays of Thornton Wilder Volume I'' (1997): ** ''

The Thornton Wilder Society

* * * Retrieved on May 18, 2009 *

Thornton Wilder Collection

at the

Biography from The Thornton Wilder Society

* Thornton Wilder Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. * Thornton Wilder Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Finding aid to Thornton Wilder letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.Guide to the Thornton Wilder Papers 1939–1968

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wilder, Thornton 1897 births 1975 deaths 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights 20th-century American novelists American Congregationalists American male novelists United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II Berkeley High School (Berkeley, California) alumni Harvard Divinity School faculty National Book Award winners Oberlin College alumni Writers from Madison, Wisconsin People from Ojai, California Princeton University alumni Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) United States Army Air Forces officers University of Chicago faculty Yale University alumni MacDowell Colony fellows United States Army colonels American male dramatists and playwrights Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients 20th-century American male writers The Thacher School alumni Novelists from California Novelists from Illinois Novelists from Massachusetts People from Maple Bluff, Wisconsin Christian novelists Military personnel from California

The Bridge of San Luis Rey

''The Bridge of San Luis Rey'' is American author Thornton Wilder's second novel. It was first published in 1927 to worldwide acclaim. The novel won the Pulitzer Prize in 1928, and was the best-selling work of fiction that year.

Premise

''The B ...

'' and for the plays '' Our Town'' and '' The Skin of Our Teeth'' — and a U.S. National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The N ...

for the novel '' The Eighth Day''.

Early years and family

Wilder was born in

Wilder was born in Madison, Wisconsin

Madison is the county seat of Dane County, Wisconsin, Dane County and the capital city of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census the population was 269,840, making it the second-largest city in Wisconsin b ...

, the son of Amos Parker Wilder

Amos Parker Wilder (February 15, 1862 – July 2, 1936) was an American journalist and diplomat who served as United States Consul General to Hong Kong and Shanghai in the early 20th century.

Early life and education

Wilder was born on September ...

, a newspaper editor and later a U.S. diplomat, and Isabella Thornton Niven.

Wilder had four siblings as well as a twin who was stillborn. All of the surviving Wilder children spent part of their childhood in China when their father was stationed in Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

and Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

as U.S. Consul General. Thornton's older brother, Amos Niven Wilder, became Hollis Professor of Divinity at the Harvard Divinity School

Harvard Divinity School (HDS) is one of the constituent schools of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school's mission is to educate its students either in the academic study of religion or for leadership roles in religion, go ...

. He was a noted poet and was instrumental in developing the field of theopoetics. Their sister Isabel Wilder

Isabel Wilder (January 13, 1900 in Madison, Wisconsin – February 27, 1995 in Hamden, Connecticut)Charlotte Wilder

Charlotte Wilder (Aug 28, 1898 – May 26, 1980 Brattleboro, Vermont) was an American poet and academic who worked in the Federal Writers Project.

Wilder published poetry in '' The Nation'' and ''Poetry Magazine''. She also published poetr ...

, a poet, and Janet Wilder Dakin

Janet Wilder Dakin (June 3, 1910 – October 7, 1994), was an American philanthropist and zoologist, known for her animal advocacy and environmental work.

Biography

Janet Frances Wilder was born in China, the daughter of Isabella Niven and Am ...

, a zoologist.

Education

Wilder began writing plays while at the Thacher School in Ojai, California, where he did not fit in and was teased by classmates as overly

Wilder began writing plays while at the Thacher School in Ojai, California, where he did not fit in and was teased by classmates as overly intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator o ...

. According to a classmate, "We left him alone, just left him alone. And he would retire at the library, his hideaway, learning to distance himself from humiliation and indifference." His family lived for a time in China, where his sister Janet was born in 1910. He attended the English China Inland Mission Chefoo School

The Chefoo School (), also known as Protestant Collegiate School or China Inland Mission School, was a Christian boarding school established in 1881 by the China Inland Mission—under James Hudson Taylor—at Chefoo (Yantai), in Shandong ...

at Yantai

Yantai, formerly known as Chefoo, is a coastal prefecture-level city on the Shandong Peninsula in northeastern Shandong province of People's Republic of China. Lying on the southern coast of the Bohai Strait, Yantai borders Qingdao on the ...

but returned with his mother and siblings to California in 1912 because of the unstable political conditions in China at the time. Thornton graduated from Berkeley High School in 1915.

After having served a three-month enlistment in the Army's Coast Artillery Corps at Fort Adams, Rhode Island, in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

(rising to the rank of corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non- ...

), he attended Oberlin College before earning his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1920 at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

, where he refined his writing skills as a member of the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity, a literary society. He earned his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. ...

degree in French literature from Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the n ...

in 1926.

Career

After graduating, Wilder went to Italy and studiedarchaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts ...

and Italian (1920–21) as part of an eight-month residency at The American Academy in Rome

The American Academy in Rome is a research and arts institution located on the Gianicolo (Janiculum Hill) in Rome.

The academy is a member of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers.

History

In 1893, a group of American architects, ...

, and then taught French at the Lawrenceville School in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, beginning in 1921. His first novel''The Cabala''

was published in 1926. In 1927, ''

The Bridge of San Luis Rey

''The Bridge of San Luis Rey'' is American author Thornton Wilder's second novel. It was first published in 1927 to worldwide acclaim. The novel won the Pulitzer Prize in 1928, and was the best-selling work of fiction that year.

Premise

''The B ...

'' brought him commercial success and his first Pulitzer Prize (1928). He resigned from the Lawrenceville School in 1928. From 1930 to 1937 he taught at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, during which time he published his translation of André Obey's own adaptation of the tale "Le Viol de Lucrece" (1931) under the title "Lucrece" (Longmans Green, 1933). In Chicago, he became famous as a lecturer and was chronicled on the celebrity pages. In 1938 he won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for his play '' Our Town'', and he won the prize again in 1943 for his play '' The Skin of Our Teeth''.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

saw Wilder rise to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Air Force Intelligence, first in Africa, then in Italy until 1945. He received several awards for his military service.The American Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight ...

and Bronze Star, ''Chevalier'' of the ''Legion d'Honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

'' from France, and an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

(MBE) from Britain. He went on to be a visiting professor at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, where he served for a year as the Charles Eliot Norton professor. Though he considered himself a teacher first and a writer second, he continued to write all his life, receiving the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1957 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963. In 1968 he won the National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The N ...

for his novel ''The Eighth Day''.

Proficient in four languages, Wilder translated plays by André Obey

André Obey (; 8 May 1892 at Douai, France – 11 April 1975 at Montsoreau, near the river Loire) was a prominent French playwright during the inter-war years, and into the 1950s.

He began as a novelist and produced an autobiographical novel abou ...

and Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialist, existentialism (and Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter ...

. He wrote the libretti of two operas, ''The Long Christmas Dinner

''The Long Christmas Dinner'' is a play in one act written by American novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder in 1931. In its first published form, it was included in the volume ''The Long Christmas Dinner and Other Plays in One Act''.

Chara ...

'', composed by Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the '' ...

, and ''The Alcestiad'', composed by Louise Talma

Louise Juliette Talma (October 31, 1906August 13, 1996) was an American composer, academic, and pianist. After studies in New York and in France, piano with Isidor Philipp and composition with Nadia Boulanger, she focused on composition from 193 ...

and based on his own play. Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

, whom he admired, asked him to write the screenplay of his thriller ''Shadow of a Doubt

''Shadow of a Doubt'' is a 1943 American psychological thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, and starring Teresa Wright and Joseph Cotten. Written by Thornton Wilder, Sally Benson, and Alma Reville, the film was nominated for an Ac ...

'', and he completed a first draft for the film.

''The Bridge of San Luis Rey'' (1927) tells the story of several unrelated people who happen to be on a bridge in Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

when it collapses, killing them. Philosophically, the book explores the question of why unfortunate events occur to people who seem "innocent" or "undeserving". It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1928, and in 1998 it was selected by the editorial board of the American Modern Library as one of the 100 best novels of the twentieth century. The book was quoted by British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern ...

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of the ...

during the memorial service for victims of the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

in 2001. Since then its popularity has grown enormously. The book is the progenitor of the modern disaster epic in literature and film-making

Filmmaking (film production) is the process by which a motion picture is produced. Filmmaking involves a number of complex and discrete stages, starting with an initial story, idea, or commission. It then continues through screenwriting, castin ...

, where a single disaster intertwines the victims, whose lives are then explored by means of flashbacks to events before the disaster.

Wilder wrote '' Our Town'', a popular play (and later film) set in fictional Grover's Corners, New Hampshire. It was inspired in part by Dante's ''Purgatorio'' and in part by his friend

Wilder wrote '' Our Town'', a popular play (and later film) set in fictional Grover's Corners, New Hampshire. It was inspired in part by Dante's ''Purgatorio'' and in part by his friend Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West (Pittsburgh), Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, Calif ...

's novel ''The Making of Americans''. Wilder suffered from writer's block while writing the final act. ''Our Town'' employs a choric narrator called the Stage Manager and a minimalist set to underscore the human experience. Wilder himself played the Stage Manager on Broadway for two weeks and later in summer stock productions. Following the daily lives of the Gibbs and Webb families, as well as the other inhabitants of Grover's Corners, the play illustrates the importance of the universality of the simple, yet meaningful lives of all people in the world in order to demonstrate the value of appreciating life. The play won the 1938 Pulitzer Prize.

In 1938, Max Reinhardt directed a Broadway production of '' The Merchant of Yonkers'', which Wilder had adapted from

In 1938, Max Reinhardt directed a Broadway production of '' The Merchant of Yonkers'', which Wilder had adapted from Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n playwright Johann Nestroy's ''Einen Jux will er sich machen

''Einen Jux will er sich machen'' (1842) (''He Will Go on a Spree'' or ''He'll Have Himself a Good Time''), is a three-act musical play, designated as a Posse mit Gesang ("farce with singing"), by Austrian playwright Johann Nestroy. It was adap ...

'' (1842). It was a failure, closing after 39 performances.

His play '' The Skin of Our Teeth'' opened in New York on November 18, 1942, featuring Fredric March

Fredric March (born Ernest Frederick McIntyre Bickel; August 31, 1897 – April 14, 1975) was an American actor, regarded as one of Hollywood's most celebrated, versatile stars of the 1930s and 1940s.Obituary '' Variety'', April 16, 1975, ...

and Tallulah Bankhead. Again, the themes are familiar – the timeless human condition; history as progressive, cyclical, or entropic; literature, philosophy, and religion as the touchstones of civilization. Three acts dramatize the travails of the Antrobus family, allegorizing the alternate history of mankind. It was claimed by Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson, authors of '' A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake'', that much of the play was the result of unacknowledged borrowing from James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the Modernism, modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important ...

's last work. Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson published a pair of reviews-cum-denunciations entitled "The Skin of ''Whose'' Teeth?" in the '' Saturday Review'' immediately after the play's debut; these created a huge uproar at the time. Campbell's reprints the reviews and discusses the controversy.

In his novel '' The Ides of March'' (1948), Wilder reconstructed the characters and events leading to, and culminating in, the assassination of Julius Caesar. He had met Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialist, existentialism (and Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter ...

on a U.S. lecture tour after the war, and was under the influence of existentialism

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning

Meaning most comm ...

, although rejecting its atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

implications.

In 1954, Tyrone Guthrie encouraged Wilder to rework ''The Merchant of Yonkers'' into '' The Matchmaker''. This time the play opened in 1955 and enjoyed a healthy Broadway run of 486 performances with Ruth Gordon in the title role, winning a

In 1954, Tyrone Guthrie encouraged Wilder to rework ''The Merchant of Yonkers'' into '' The Matchmaker''. This time the play opened in 1955 and enjoyed a healthy Broadway run of 486 performances with Ruth Gordon in the title role, winning a Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual ce ...

for Guthrie, its director. It became the basis for the hit 1964 musical '' Hello, Dolly!'', with a book by Michael Stewart and score by Jerry Herman.

In 1960, Wilder was awarded the first ever Edward MacDowell Medal by The MacDowell Colony for outstanding contributions to American culture.

In 1962 and 1963, Wilder lived twenty months in the small town of Douglas, Arizona

Douglas is a city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States that lies in the north-west to south-east running Sulpher Springs Valley. Douglas has a border crossing with Mexico at Agua Prieta and a history of mining.

The population was 16,531 ...

, apart from family and friends. There he started his longest novel, ''The Eighth Day'', which went on to win the National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The N ...

. According to Harold Augenbraum in 2009, it "attack dthe big questions head on, ... mbeddedin the story of small-town America".

His last novel, '' Theophilus North'', was published in 1973, and made into the film '' Mr. North'' in 1988.

The Library of America republished all of Wilder's plays in 2007, together with some of his writings on the theater and the screenplay of ''Shadow of a Doubt''. In 2009, a second volume was released, containing his first five novels, six early stories, and four essays on fiction. Finally, the third and final volume in the Library of America series on Wilder was released in 2011, containing his last two novels ''The Eighth Day'' and ''Theophilus North'', as well as four autobiographical sketches.

Personal life

Six years after Wilder’s death, Samuel Steward wrote in his autobiography that he had sexual relations with him. In 1937,Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West (Pittsburgh), Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, Calif ...

had given Steward, then a college professor, a letter of introduction to Wilder. According to Steward, Alice B. Toklas

Alice Babette Toklas (April 30, 1877 – March 7, 1967) was an American-born member of the Parisian avant-garde of the early 20th century, and the life partner of American writer Gertrude Stein.

Early life

Alice B. Toklas was born in San F ...

told him that Wilder liked him and that Wilder had reported he was having trouble starting the third act of ''Our Town'' until he and Steward walked around Zürich all night in the rain and the next day wrote the whole act, opening with a crowd in a rainy cemetery. Penelope Niven disputes Steward's claim of a relationship with Wilder and, based on Wilder's correspondence, says Wilder started work on the third act of ''Our Town'' and completed it several months later, and all of this happened before his first meeting with Samuel Steward.

Robert Gottlieb, reviewing Penelope Niven's work in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issue ...

'' in 2013, claimed Wilder had become infatuated by a man, not identified by Gottlieb, and Wilder’s feeling were not reciprocated. Gottlieb asserted that "Niven ties herself in knots in her discussion of Wilder’s confusing sexuality" and that "His interest in women was unshakably nonsexual." He takes Steward's view that Wilder was a latent homosexual but never comfortable with sex.

Wilder had a wide circle of friends, including writers Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Zelda Fitzgerald, Toklas, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialist, existentialism (and Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter ...

, and Stein; actress Ruth Gordon; fighter Gene Tunney; and socialite Sibyl, Lady Colefax.

Death

From the earnings of ''The Bridge of San Luis Rey'', in 1930 Wilder built a house for his family in Hamden, Connecticut. His sister Isabel lived there for the rest of her life. This became his home base, although he traveled extensively and lived away for significant periods. He died in this house on December 7, 1975, ofheart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, ...

. He was interred at Mount Carmel Cemetery, Hamden, Connecticut.

Bibliography

Plays

* ''The Trumpet Shall Sound'' (1926) * ''The Angel That Troubled the Waters and Other Plays'' (1928): **"Nascuntur Poetae" **"Proserpina and the Devil" **"Fanny Otcott" **"Brother Fire" **"The Penny That Beauty Spent" **"The Angel on the Ship" **"The Message and Jehanne" **"Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came" **"Centaurs" **"Leviathan" **"And the Sea Shall Give Up Its Dead" **"The Servant's Name Was Malchus" **"Mozart and the Gray Steward" **"Hast Thou Considered My Servant Job?" **"The Flight Into Egypt" **"The Angel That Troubled the Waters" * ''The Long Christmas Dinner and Other Plays in One Act'' (1931): ** ''The Long Christmas Dinner

''The Long Christmas Dinner'' is a play in one act written by American novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder in 1931. In its first published form, it was included in the volume ''The Long Christmas Dinner and Other Plays in One Act''.

Chara ...

''

** ''Queens of France''

** ''Pullman Car Hiawatha''

** ''Love and How to Cure It''

** ''Such Things Only Happen in Books''

** '' The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden''

* '' Our Town'' (1938)—won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama"Drama"''Past winners & finalists by category''. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved March 28, 2012. * '' The Merchant of Yonkers'' (1938) * '' The Skin of Our Teeth'' (1942)—won the Pulitzer Prize * '' The Matchmaker'' (1954)—revised from ''The Merchant of Yonkers'' * ''The Alcestiad: Or, a Life in the Sun'' (1955) * ''Childhood'' (1960) * ''Infancy'' (1960) * ''Plays for Bleecker Street'' (1962) * ''The Collected Short Plays of Thornton Wilder Volume I'' (1997): ** ''

The Long Christmas Dinner

''The Long Christmas Dinner'' is a play in one act written by American novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder in 1931. In its first published form, it was included in the volume ''The Long Christmas Dinner and Other Plays in One Act''.

Chara ...

''

** ''Queens of France''

** ''Pullman Car Hiawatha''

** ''Love and How to Cure It''

** ''Such Things Only Happen in Books''

** '' The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden''

** ''The Drunken Sisters''

** ''Bernice''

** ''The Wreck on the Five-Twenty-Five''

** ''A Ringing of Doorbells''

** ''In Shakespeare and the Bible''

** ''Someone from Assisi''

** ''Cement Hands''

** ''Infancy''

** ''Childhood''

** ''Youth''

** ''The Rivers Under the Earth''

** ''Our Town''

Films

* ''Shadow of a Doubt

''Shadow of a Doubt'' is a 1943 American psychological thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, and starring Teresa Wright and Joseph Cotten. Written by Thornton Wilder, Sally Benson, and Alma Reville, the film was nominated for an Ac ...

'' (1943)

Novels

* ''The Cabala'' (1926) * ''The Bridge of San Luis Rey

''The Bridge of San Luis Rey'' is American author Thornton Wilder's second novel. It was first published in 1927 to worldwide acclaim. The novel won the Pulitzer Prize in 1928, and was the best-selling work of fiction that year.

Premise

''The B ...

'' (1927)—won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published durin ...

* ''The Woman of Andros

''The Woman of Andros'' is a 1930 novel by Thornton Wilder. Inspired by ''Andria'', a comedy by Terence, it was the third-best selling book in the United States in 1930.

The novel is set on the fictional Greek island of Brynos in the pre-Chr ...

'' (1930)—based on '' Andria'', a comedy by Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

* ''Heaven's My Destination'' (1935)

* '' Ides of March'' (1948)

* '' The Eighth Day'' (1967)—won the National Book Award for Fiction (With an essay by Harold Augenbraum from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.)

* '' Theophilus North'' (1973)—reprinted as ''Mr. North'' following the appearance of the film of the same name

Collections

* * *Further reading

* Gallagher-Ross, Jacob. 2018. "Theaters of the Everyday". Evanston: Northwestern University Press. . * * Kennedy, Harold J. 1978. "No Pickle, No Performance. An Irreverent Theatrical Excursion from Tallulah to Travolta". Doubleday & Co.Notes

References

External links

*The Thornton Wilder Society

* * * Retrieved on May 18, 2009 *

Thornton Wilder Collection

at the

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pu ...

*

Biography from The Thornton Wilder Society

* Thornton Wilder Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. * Thornton Wilder Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Finding aid to Thornton Wilder letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wilder, Thornton 1897 births 1975 deaths 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights 20th-century American novelists American Congregationalists American male novelists United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II Berkeley High School (Berkeley, California) alumni Harvard Divinity School faculty National Book Award winners Oberlin College alumni Writers from Madison, Wisconsin People from Ojai, California Princeton University alumni Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) United States Army Air Forces officers University of Chicago faculty Yale University alumni MacDowell Colony fellows United States Army colonels American male dramatists and playwrights Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients 20th-century American male writers The Thacher School alumni Novelists from California Novelists from Illinois Novelists from Massachusetts People from Maple Bluff, Wisconsin Christian novelists Military personnel from California