Thomas Hines on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Henry Hines (October 8, 1838 – January 23, 1898) was a

In June 1863, Hines led an invasion into Indiana with 25 Confederates posing as a U.S. unit in pursuit of deserters. Their goal was to see if the local

In June 1863, Hines led an invasion into Indiana with 25 Confederates posing as a U.S. unit in pursuit of deserters. Their goal was to see if the local

After his time on the Kentucky Court of Appeals, Hines returned to practicing law in

After his time on the Kentucky Court of Appeals, Hines returned to practicing law in

Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

cavalryman who was known for his espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

activities during the last two years of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

A native of Butler County, Kentucky

Butler County is a county located in the US state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 12,371. Its county seat is Morgantown. The county was formed in 1810, becoming Kentucky's 53rd county. Butler County is included in the ...

, he initially worked as a grammar instructor, mainly at the Masonic University of La Grange, Kentucky

La Grange is a home rule-class city in Oldham County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 10,067 at the time of the 2020 U.S. census. It is the seat of its county. A unique feature of the city is the CSX Transportation street-ru ...

. During the first year of the war, he was a field officer, initiating several raids. He was an assistant to John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan (June 1, 1825September 4, 1864) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War. In April 1862, he raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, fought at Shiloh, and then launched a costly raid in Kentucky, which encouraged Br ...

, doing a preparatory raid ( Hines' Raid) in advance of Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid (also the Calico Raid or Great Raid of 1863) was a diversionary incursion by Confederate States Army, Confederate cavalry into the Union (American Civil War), Union states of Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia during the A ...

through the states of Indiana and Ohio, and after being captured with Morgan, organized their escape from the Ohio Penitentiary

The Ohio Penitentiary, also known as the Ohio State Penitentiary, was a prison operated from 1834 to 1984 in downtown Columbus, Ohio, in what is now known as the Arena District. The state had built a small prison in Columbus in 1813, but as th ...

. He was then granted secret authorisation, following the Dahlgren Affair

The Dahlgren affair was an incident during the American Civil War which stemmed from a failed Union raid on the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia in March 1864. Brigadier General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick and Colonel Ulric Dahlgren led an a ...

, by Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

and his cabinet to unleash total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all (including civilian-associated) resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilises all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare ov ...

behind Union lines. From a secret base at Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

in Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada () was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Queb ...

, Hines oversaw Confederate Secret Service

The Confederate Secret Service refers to any of a number of official and semi-official secret service organizations and operations performed by the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. Some of the organizations were directe ...

covert operation

A covert operation or undercover operation is a military or police operation involving a covert agent or troops acting under an assumed cover to conceal the identity of the party responsible.

US law

Under US law, the Central Intelligence A ...

s with Copperhead Democrat leaders Harrison H. Dodd and Clement Vallandigham

Clement Laird Vallandigham ( ; July 29, 1820 – June 17, 1871) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the leader of the Copperhead (politics), Copperhead faction of Opposition to the American Civil War, anti-war History of the Unit ...

for arson

Arson is the act of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, watercr ...

, state terrorism

State terrorism is terrorism conducted by a state against its own citizens or another state's citizens.

It contrasts with '' state-sponsored terrorism'', in which a violent non-state actor conducts an act of terror under sponsorship of a state. ...

, guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

, and pro-Confederate regime change

Regime change is the partly forcible or coercive replacement of one government regime with another. Regime change may replace all or part of the state's most critical leadership system, administrative apparatus, or bureaucracy. Regime change may ...

uprisings by the paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

Order of the Sons of Liberty against pro-Union governors throughout the Old Northwest

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

.

Hines made narrow, unlikely escapes on several occasions during the war. At one point, he concealed himself in a mattress that was being used at the time; on another occasion, he was confused for the actor and assassin John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

, a dangerous case of mistaken identity that forced him to flee Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

in April 1865 by holding a ferry captain at gunpoint. Union agents viewed Hines as the man they most needed to apprehend, but apart from the time he served at the Ohio Penitentiary in late 1863, he was never captured.

After the war, once it was safe for him to return to his native Kentucky, he settled down with much of his family in Bowling Green

A bowling green is a finely laid, close-mown and rolled stretch of turf for playing the game of bowls.

Before 1830, when Edwin Beard Budding of Thrupp, near Stroud, UK, invented the lawnmower, lawns were often kept cropped by grazing sheep ...

. He started practicing law, which led him to serve on the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illino ...

, eventually becoming its chief justice. Later, he practiced law in Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It is a list of Kentucky cities, home rule-class city and the county seat, seat of Franklin County, Kentucky, Franklin County in the Upland Sou ...

, until he died in 1898, keeping many of the secrets of Confederate espionage from public knowledge.

Early life

Hines was born inButler County, Kentucky

Butler County is a county located in the US state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 12,371. Its county seat is Morgantown. The county was formed in 1810, becoming Kentucky's 53rd county. Butler County is included in the ...

, on October 8, 1838, to Judge Warren W. and Sarah Carson Hines and was raised in Warren County, Kentucky

Warren County is a county located in the south central portion of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 134,554, making it the fifth-most populous county in Kentucky. The county seat is Bowling Green. Warren ...

. While his education was largely informal, he spent some time in common schools. He was tall, and weighed a mere . With his slender build, Hines was described as rather benign in appearance, and a friend observed that he had a voice resembling a "refined woman". He was said to love women, music, and horses fondly.

He became an adjunct professor at the Masonic University, a school established by the Grand Lodge of Kentucky

The Grand Lodge of Kentucky is one of two state organizations that supervise Masonic lodges in the state of Kentucky. It was established in 1800.

The Grand Lodge of Virginia (GLVA) established Lexington Lodge #25, the first Masonic lodge west o ...

Freemasons

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

for teaching the orphans of Kentucky Masons in La Grange in 1859. He was the principal of its grammar school, but with the advent of the war, he joined the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the Military forces of the Confederate States, military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) duri ...

in September 1861.

American Civil War

Early war experiences

Hines joined the Confederate army, as did at least eleven cousins.Horan, p. 4. Hines initially led "Buckner's Guides", which were attached toAlbert Sidney Johnston

General officer, General Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) was an American military officer who served as a general officer in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States ...

's command, as his fellow guides recognized his "coolness and leadership". In November 1861, he was given a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

's commission. On December 31, 1861, he led a successful mission to Borah's Ferry, Kentucky, to attack a Union outpost there.

The Guides were disbanded in January 1862 after the Confederate government of Kentucky

The Confederate government of Kentucky was a government-in-exile, shadow government established for the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Kentucky by a self-constituted group of Confederate States of America, Confederate sympathizer ...

fled Bowling Green; Hines did not want to fight anywhere except in Kentucky. He traveled to Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, and missed the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the American Civil War fought on April 6–7, 1862. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater of the ...

as a result. In April, Hines decided to join Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan (June 1, 1825September 4, 1864) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War. In April 1862, he raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, fought at Shiloh, and then launched a costly raid in Kentucky, which encouraged Br ...

, and he re-enlisted in the army as a private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

in the 9th Kentucky Cavalry in May 1862. Morgan commissioned Hines as a captain on June 10, 1862. Afterward, Hines spent most of his time conducting espionage in Kentucky. Dressed in civilian clothes, he usually operated alone to avoid drawing attention to himself, not wanting to be executed as a spy.

Hines made special trips to see loved ones on his forays in Kentucky. Often, it was to visit Nancy Sproule, his childhood sweetheart and future bride, in Brown's Lock, near Bowling Green. On other occasions, he visited his parents in Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city coterminous with and the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census the city's population was 322,570, making it the List of ...

. In both places, U.S. authorities attempted to capture Hines, but he always escaped, even after his father had been captured and his mother was sick in bed.

1863

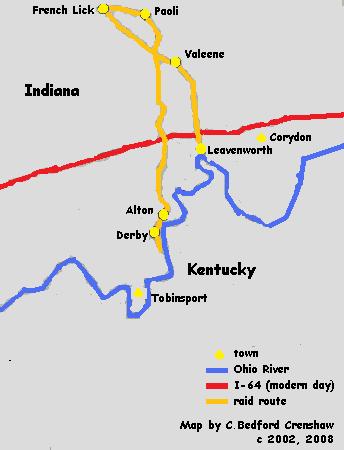

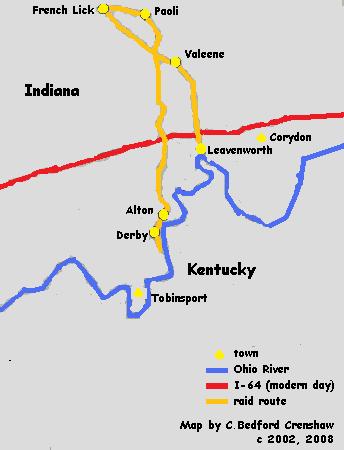

In June 1863, Hines led an invasion into Indiana with 25 Confederates posing as a U.S. unit in pursuit of deserters. Their goal was to see if the local

In June 1863, Hines led an invasion into Indiana with 25 Confederates posing as a U.S. unit in pursuit of deserters. Their goal was to see if the local Copperheads

Copperhead may refer to:

Snakes

* ''Agkistrodon contortrix'', or eastern copperhead, a venomous pit viper species found in parts of North America

* '' Agkistrodon laticinctus'', or broad-banded copperhead, a pit viper species found in the southe ...

would support the invasion that John Hunt Morgan planned for July 1863. Traveling through Kentucky for eight days to obtain supplies for their mission, they crossed the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

to enter Indiana, near the village of Derby

Derby ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area on the River Derwent, Derbyshire, River Derwent in Derbyshire, England. Derbyshire is named after Derby, which was its original co ...

, on June 18, 1863. Hines visited the local Copperhead leader, Dr. William A. Bowles, in French Lick

French Lick is a town in French Lick Township, Orange County, Indiana, United States. The population was 1,722 at the time of the 2020 census.

History

French Lick was originally a French trading post built near a spring and salt lick. A for ...

, and learned that there would be no formal support for Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid (also the Calico Raid or Great Raid of 1863) was a diversionary incursion by Confederate States Army, Confederate cavalry into the Union (American Civil War), Union states of Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia during the A ...

. On his way back to Kentucky, Hines and his men were discovered in Valeene, Indiana, leading to a minor skirmish near Leavenworth, Indiana

Leavenworth is a town in Jennings Township, Crawford County, Indiana, along the Ohio River. The 2010 US Census recorded a population of 238 persons.

History

Foundation and early settlement

Leavenworth was laid out in 1818 in a horseshoe s ...

, on Little Blue Island. Hines abandoned his men, swimming across the Ohio River under gunfire.

After wandering around Kentucky for a week, Hines rejoined Morgan at Brandenburg, Kentucky

Brandenburg is a home rural-class city on the Ohio River in Meade County, Kentucky, in the United States. The city is southwest of Louisville. It is the seat of its county. The population was 2,894 at the 2020 census.

History

Brandenburg ...

. Colonel Basil W. Duke made a disparaging comment in his memoirs about how Hines appeared on the Brandenburg riverfront, saying Hines was "apparently the most listless inoffensive youth that was ever imposed upon"; despite being Morgan's second-in-command, Duke was usually not told of all the espionage Hines was carrying out, causing some to believe that Hines and Duke did not like each other, which was not the case.

It was due to Hines that the riverboats ''Alice Dean

PS ''Alice Dean'', which had a capacity of 880 tons, was a side-wheel, wooden-hulled packet steamer. It was launched from Cincinnati, Ohio, United States, in 1863, running a scheduled route between Cincinnati and Memphis, Tennessee. Its captain w ...

'' and the '' John T. McCombs'' were captured to transport Morgan's 2000+ men force across the Ohio River. Hines' reports encouraged Morgan to be rough with anyone posing as a Confederate sympathizer in Indiana, as Morgan had been relying on support from sympathizers in Indiana to be successful in his raid. Hines stayed with Morgan until the end of the raid and was with John Hunt Morgan during their imprisonment as prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

, first at Johnson's Island

Johnson's Island is a island in Sandusky Bay, located on the coast of Lake Erie, from the city of Sandusky, Ohio. It was the site of a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederate officers captured during the American Civil War. Initially, ...

, and later at the Ohio Penitentiary just outside downtown Columbus, Ohio

Columbus (, ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Ohio, most populous city of the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 United States census, 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the List of United States ...

.

Escape

Hines discovered a way to escape from the Ohio Penitentiary. He had been reading the novel ''Les Misérables

''Les Misérables'' (, ) is a 19th-century French literature, French Epic (genre), epic historical fiction, historical novel by Victor Hugo, first published on 31 March 1862, that is considered one of the greatest novels of the 19th century. '' ...

'' and was said to be inspired by Jean Valjean

Jean Valjean () is the protagonist of Victor Hugo's 1862 novel ''Les Misérables''. The story depicts the character's struggle to lead a normal life and redeem himself after serving a 19-year-long prison sentence for stealing bread to feed his ...

and Valjean's escapes through the passages underneath Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. Hines noticed how dry the lower prison cells felt and how they were lacking in mold

A mold () or mould () is one of the structures that certain fungus, fungi can form. The dust-like, colored appearance of molds is due to the formation of Spore#Fungi, spores containing Secondary metabolite#Fungal secondary metabolites, fungal ...

, even though sunlight never shined there. This caused him to believe that escape by tunneling down was possible. After discovering an air chamber underneath them, which he had deduced, Hines began the tunneling effort. The tunnel was only eighteen inches wide, just large enough for him to enter the four-foot by four-foot air chamber surrounded by heavy masonry. As Hines and the six others who accompanied Hines and John Hunt Morgan worked on the tunnel, a thin crust of dirt was used to hide the tunnel from the prison officials. They tunneled for six weeks, with the tunnel's exit coming between the inner and the outer prison walls, near a coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

pile. On the day of escape, November 26, 1863, Morgan switched cells with his brother, Richard Morgan. The day was chosen as a new Union military commander was coming to Columbus, and Morgan knew the prison cells would be inspected then. Together, after the daily midnight inspection, Hines, John Hunt Morgan, and five captains under Morgan's command used the tunnel to escape. Aided by the fact that the prison sentries sought shelter from the raging storm occurring at the time, the Confederate officers climbed the wall effortlessly, using metal hooks to effect their escape.

Hines left a note for "Warden N. Merion, the Faithful, the Vigilant" that read, "Castle Merion, Cell No. 20. November 27, 1863. Commencement, November 4, 1863. Conclusion, November 20, 1863. Hours for labor per day, three. Tools, two small knives. ''La patience est amere, mais son fruit est doux.'' By order of my six honorable confederates." Those left behind were strip searched and moved to different cells in the Ohio State Penitentiary. Two of the officers who escaped with Hines and Morgan, Ralph Sheldon and Samuel Taylor, were captured four days later in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

. Still, the other three (Captain Jacob Bennett, Captain L. D. Hockersmith, and Captain Augustus Magee) escaped to Canada and the Confederacy.

Hines led John Hunt Morgan back to Confederate lines. First, they arrived at the train station in downtown Columbus, where they bought tickets to Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

. The duo jumped off the train before it entered the Cincinnati train station. They continued to evade capture in Cincinnati, staying for one night at the Ben Johnson House in Bardstown, Kentucky

Bardstown is a list of Kentucky cities, home rule-class city in Nelson County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 13,567 in the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is the list of counties in Kentucky, county seat of Nelson Count ...

. In Tennessee, Hines diverted the Union troops' attention away from Morgan and was himself recaptured and sentenced to death by hanging. He escaped that night by telling stories to the soldier in charge of him and subdued him when given the chance. A few days later, he again escaped U.S. soldiers who intended to hang him.

Northwest Conspiracy

Hines traveled toRichmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, after his escape in January 1864. He convinced Confederate President

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the unrecognized breakaway Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and commander-in-chief of the Confederate Ar ...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

of a plan to instill mass panic in the northern states by freeing prisoners and systematic arson

Arson is the act of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, watercr ...

in the larger U.S. cities. Impressed by Hines' plan and wishing to retaliate for the Dahlgren affair

The Dahlgren affair was an incident during the American Civil War which stemmed from a failed Union raid on the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia in March 1864. Brigadier General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick and Colonel Ulric Dahlgren led an a ...

, Davis agreed to back him. Davis urged Hines to tell Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin and Secretary of War James Seddon

James Alexander Seddon (July 13, 1815 – August 19, 1880) was an American lawyer and politician who served two terms as a Representative in the United States Congress, as a member of the Democratic Party. Seddon was appointed Confederate ...

his plan. Both men agreed to the project and encouraged Hines to proceed, with the only hesitation by Davis, Benjamin, and Sheldon being the potentially damaging effect on public opinion of the exposure of such a plan, including what Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire, officially the French Empire, was the government of France from 1852 to 1870. It was established on 2 December 1852 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, president of France under the French Second Republic, who proclaimed hi ...

would think of Hines' actions.

Hines thought entering the Union from Canada would be easier and traveled there during the winter. Hines led the Northwest Conspiracy

Thomas Henry Hines (October 8, 1838 – January 23, 1898) was a Confederate States of America, Confederate cavalryman who was known for his espionage activities during the last two years of the American Civil War.

A native of Butler County, ...

from Canada in the fall of 1864. Colonel Benjamin Anderson was involved in the plot, along with other Confederate soldiers. It was hoped that Hines and his men would be able to free the Confederate prisoners held at Camp Douglas in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

.Horan, pp. 192-93.

Hines led sixty men from Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

, Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

, on August 25, 1864. They arrived during the Democratic Party National Convention in Chicago that year. The Copperheads had told Hines to wait until that time, as they said that 50,000 Copperheads would be there for the event. However, encountering Copperhead hesitation to assist Hines and his force, and with U.S. authorities knowledgeable of the plot, Hines and his men were forced to flee Chicago on August 30, 1864. Many men thought Anderson may have been a double agent, forcing him to leave the group. A second attempt to free the Camp Douglas Confederate prisoners occurred during the United States Presidential Election of 1864, but that plan was also foiled.

In the same year, he tried to free Confederate prisoners of war by recruiting former members of Morgan's Raiders who had escaped to Canada, including John Hunt Morgan's telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

er George "Lightning" Ellsworth, who was a native of Canada. On his last day in Chicago, Hines had to avoid discovery by U.S. soldiers inspecting the home he was hiding in by crawling into a mattress upon which the homeowner's wife lay ill with delirium. The soldiers inspected the house he was in and even checked to see if Hines was lying on the bed, but they did not discover Hines in the mattress. The soldiers established a guard by the door of the house. Visitors were encouraged to visit the sick woman as it rained the next day. The soldiers never looked at the faces under the umbrellas, so Hines sneaked out of the house and left Chicago.

Late war

In October 1864, Hines again went to Cincinnati after crossing covertly through Indiana, where U.S. troops sought him again. This time, with the help of friends whose home he hid in, Hines concealed himself in an old closet obscured by mortar and red bricks, where he avoided detection by the troops who inspected the house. Hines learned there that his beloved Nancy Sproule was in an Ohioconvent

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

. He decided to "spirit" her from it. On November 10, 1864, at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Covington, Kentucky

Covington is a list of cities in Kentucky, home rule-class city in Kenton County, Kentucky, United States. It is located at the confluence of the Ohio River, Ohio and Licking River (Kentucky), Licking rivers, across from Cincinnati to the north ...

, they were married, despite her father's wishes to wait until the war was over due to Hines' wartime activities. They spent a week's honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds after their wedding to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase in a couple ...

in Kentucky, after which Hines returned to his clandestine activities in Canada.

Two days after Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was shot by John Wilkes Booth while attending the play '' Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. Shot in the head as he watched the play, L ...

, on April 16, 1865, Hines was in Detroit, Michigan, when he was mistaken for John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

, who was then the subject of a massive search. After finding himself in a fight, Hines jumped several fences and made his way to Detroit's wharf

A wharf ( or wharfs), quay ( , also ), staith, or staithe is a structure on the shore of a harbour or on the bank of a river or canal where ships may dock to load and unload cargo or passengers. Such a structure includes one or more Berth (mo ...

. He waited for a ferryboat

A ferry is a boat or ship that transports passengers, and occasionally vehicles and cargo, across a body of water. A small passenger ferry with multiple stops, like those in Venice, Italy, is sometimes referred to as a water taxi or water bus.

...

to empty its passengers and then forced the captain at gunpoint to take him across the Detroit River

The Detroit River is an List of international river borders, international river in North America. The river, which forms part of the border between the U.S. state of Michigan and the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ont ...

to Canada. On arrival, Hines apologized to the captain and gave him five dollars. Hines' exploit led to the mistaken rumor that Booth had escaped into Canada.

Later life

After he fled Detroit, Hines went toToronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

, where several other former Confederates lived. He did not expect to return to the United States, so he sent for his wife, Nancy. In Toronto, he studied law with General John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American politician who served as the 14th vice president of the United States, with President James Buchanan, from 1857 to 1861. Assuming office at the age of 36, Breckinrid ...

, a former Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

. Once U.S. President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

declared a pardon for most former Confederates, Hines returned to Detroit to sign a loyalty oath to the United States on July 20, 1865. However, knowing that U.S. officials in Kentucky would consider him an exception to the pardon, he remained in Canada until May 1866.

After sending his wife to Kentucky, where their first child was born, Hines began living in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

, passing the bar exam on June 12, 1866, with high honors. During his stay in Memphis, he edited the '' Daily Appeal''. Hines moved to Bowling Green, Kentucky

Bowling Green is a city in Warren County, Kentucky, United States, and its county seat. Its population was 72,294 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in Kentucky, third-most populous city in the stat ...

, in 1867, where many of his family lived and practiced law. Basil W. Duke appointed Hines a colonel in the Soldiers of the Red Cross. Hines later became the County Judge for Warren County, Kentucky

Warren County is a county located in the south central portion of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 134,554, making it the fifth-most populous county in Kentucky. The county seat is Bowling Green. Warren ...

.

Hines was elected to the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illino ...

in 1878 and served there until 1886. From 1884 to 1886, he served as Chief Justice. He was said to be "exceptionally free from all judicial bias." Hines was a witness to the assassination of fellow judge John Milton Elliott

John Milton Elliott (May 16, 1820 – March 26, 1879) was an American lawyer, politician, and judge from Prestonsburg, Kentucky. He was assassinated by a fellow judge. Elliott represented Kentucky in the United States House of Representatives from ...

on March 26, 1879, while the two were leaving the Kentucky State House, by Colonel Thomas Buford, a judge from Henry County, Kentucky

Henry County is a county located in the north central portion of the U.S. state of Kentucky bordering the Kentucky River. As of the 2020 census, the population was 15,678. Its county seat is New Castle, but its largest city is Eminence. T ...

. Buford, enraged by Elliott's failure to rule in favor of his late sister in a property dispute, shot Elliott with a double-barreled twelve-gauge shotgun

A shotgun (also known as a scattergun, peppergun, or historically as a fowling piece) is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed to shoot a straight-walled cartridge (firearms), cartridge known as a shotshell, which discharges numerous small ...

filled with buckshot

A shotgun cartridge, shotshell, or shell is a type of rimmed, cylindrical (straight-walled) ammunition used specifically in shotguns. It is typically loaded with numerous small, spherical sub-projectiles called shot. Shotguns typically use a ...

after Hines had turned and walked away from Elliott. Hines inspected the body as Buford surrendered to a deputy sheriff who had come to investigate the turmoil.

After his time on the Kentucky Court of Appeals, Hines returned to practicing law in

After his time on the Kentucky Court of Appeals, Hines returned to practicing law in Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It is a list of Kentucky cities, home rule-class city and the county seat, seat of Franklin County, Kentucky, Franklin County in the Upland Sou ...

. In 1886, Hines began writing four articles discussing the Northwest Conspiracy for Basil W. Duke's '' Southern Bivouac'' magazine. The magazine espoused the Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, known simply as the Lost Cause, is an American pseudohistory, pseudohistorical and historical negationist myth that argues the cause of the Confederate States of America, Confederate States during the America ...

but was less adversarial than similar Neo-Confederate

Neo-Confederates are groups and individuals who portray the Confederate States of America and its actions during the American Civil War in a positive light. The League of the South (formed in 1994), the Sons of Confederate Veterans (formed 1896 ...

magazines, gaining a larger Northern readership than similar journals. The first of the articles was printed in the December 1886 issue. However, after consulting with Jefferson Davis at Davis' home in Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, Hines did not name anybody on the Northern side who assisted in the conspiracy. After writing the first article, Hines was attacked for not being more forthcoming regarding all the participants from both newspapers' reviewers (particularly from the ''Louisville Times

''The Louisville Times'' was a newspaper that was published in Louisville, Kentucky. It was founded in 1884 by Walter N. Haldeman, as the afternoon counterpart to ''The Courier-Journal'', the dominant morning newspaper in Louisville and the common ...

)'' and Southern readers, which discouraged Hines from publishing any more accounts of the Northwest Conspiracy.

Hines died in 1898 in Frankfort and was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Bowling Green, Kentucky, in the Hines series of plots. Also among the Hines family plots is the grave site of Duncan Hines

Duncan Hines (March 26, 1880 – March 15, 1959) was an American author and food critic known for his restaurant ratings for travelers. He is best known today for the brand of food products that bears his name.

Early life, family and education

...

, a second cousin twice removed.

Misinformation

Historical markers concerning Hines' deeds have occasionally included mistaken information. The historical marker placed by the Indiana Civil War Centennial Commission in 1963 in the vicinity of Derby, Perry County, Indiana, to memorialize Hines' entry into Indiana states that Hines invaded Indiana in 1862, although he did so in 1863. In addition, a marker by the Confederate Monument of Bowling Green in Bowling Green's Fairview Cemetery says that Hines died before he could go to the dedication ceremony in 1876 when, in reality, he died in 1898 and is buried a few hundred feet away.Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * - Historical Article about Thomas Hines. {{DEFAULTSORT:Hines, Thomas 1838 births 1898 deaths 19th-century Kentucky state court judges American arsonists American escapees American Civil War prisoners of war held by the United States American Civil War spies Escapees from United States military detention Confederate States Army officers Judges of the Kentucky Court of Appeals People from Butler County, Kentucky People from Warren County, Kentucky People of Kentucky in the American Civil War