The Troubles In Ulster (1920–1922) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Troubles in Ulster of the 1920s was a period of conflict in the Irish province of

The Troubles in Ulster of the 1920s was a period of conflict in the Irish province of

In the early 20th century, all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. A majority of Ireland's people were

In the early 20th century, all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. A majority of Ireland's people were

In the 1920s, temporary

In the 1920s, temporary

In response to the expulsions of Catholic workers in Belfast and requirements for employment (political loyalty tests and the requirement to sign loyalty declarations to the British Government), northern Sinn Féin members called for the

In response to the expulsions of Catholic workers in Belfast and requirements for employment (political loyalty tests and the requirement to sign loyalty declarations to the British Government), northern Sinn Féin members called for the

Sectarian attacks also occurred in

Sectarian attacks also occurred in

In spring 1922,

In spring 1922,

"Partition at 100: IRA's Northern Offensive of May 1922 was doomed to disastrous failure"

''

During the Northern Offensive, there were clashes between the IRA and British forces in an area known as the 'Belleek-Pettigo salient'.Barton, Brian (1976). "Northern Ireland, 1920–25", in ''A New History of Ireland Volume VII''. Oxford University Press, p. 180 This was a triangular area of land in

During the Northern Offensive, there were clashes between the IRA and British forces in an area known as the 'Belleek-Pettigo salient'.Barton, Brian (1976). "Northern Ireland, 1920–25", in ''A New History of Ireland Volume VII''. Oxford University Press, p. 180 This was a triangular area of land in

https://jstor.org/stable/community.29825522 . Accessed 7 Feb. 2025.

* Lawlor, Pearse (2009), ''The Burnings 1920,'' Mercier Press

* MacEoin, Uinseann, (1981), ''Survivors'', Argenta Publications

* McCarthy, Pat, (2015),''The Irish Revolution, 1912–23'', Four Courts Press, Dublin,

* McNally Jack, (1987), ''Morally Good, Politically Bad'', Andersontown News Publications

* Phoenix, Eamon, (1994), ''Northern Nationalism'' Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast

* Thorne, Kathleen, (2014), ''Echoes of Their Footsteps, The Irish Civil War 1922–1924'', Generation Organization, Newberg, OR,

{{DEFAULTSORT:The Troubles in Northern Ireland (1920-1922)

Military history of Belfast

History of Ireland (1801–1923)

Irish War of Independence

Irish nationalism

Unionism in Ireland

Riots and civil disorder in Northern Ireland

Riots and civil disorder in Belfast

Attacks on buildings and structures in Belfast

The Troubles (Northern Ireland)

Sectarian violence

Catholic–Protestant sectarian violence

Anti-Catholicism in Northern Ireland

1920s in Ireland

1920s crimes in Northern Ireland

20th-century military history of the United Kingdom

Irish republicanism

The Troubles in Ulster of the 1920s was a period of conflict in the Irish province of

The Troubles in Ulster of the 1920s was a period of conflict in the Irish province of Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

, from June 1920 until June 1922, during and after the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

and the partition of Ireland

The Partition of Ireland () was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland (the area today known as the R ...

(and specifically of Ulster). In Ulster, it was mainly a communal conflict between unionists, who wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, and nationalists

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, Id ...

, who backed Irish independence: the unionists were mainly Ulster Protestants

Ulster Protestants are an ethnoreligious group in the Provinces of Ireland, Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about 43.5% of the population. Most Ulster Protestantism in Ireland, Protestants are descendants of settlers who arrived fr ...

and the nationalists were mainly Irish Catholics

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

. During this period, more than 500 people were killed in Belfast alone, 500 interned and 23,000 people were made homeless in the city, while approximately 50,000 people fled the province due to intimidation. Most of the victims were Nationalists (73%) with civilians being far more likely to be killed compared to the military, police or paramilitaries.

During the Irish War of Independence, the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various Resistance movement, resistance organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dominantly Catholic and dedicated to anti-imperiali ...

(IRA) attacked British security forces throughout the island; loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

often attacked the Catholic community in retaliation. In July 1920, they drove 8,000 mostly Catholic workers out of the Belfast shipyards sparking sectarian violence

Sectarian violence or sectarian strife is a form of communal violence which is inspired by sectarianism, that is, discrimination, hatred or prejudice between different sects of a particular mode of an ideology or different sects of a religion wi ...

in the city. That summer, violence also erupted in Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry, is the second-largest City status in the United Kingdom, city in Northern Ireland, and the fifth-largest on the island of Ireland. Located in County Londonderry, the city now covers both banks of the River Fo ...

, leaving twenty people dead, and there were mass burnings of Catholic property and expulsions of Catholics from their homes in Dromore, Lisburn

Lisburn ( ; ) is a city in Northern Ireland. It is southwest of Belfast city centre, on the River Lagan, which forms the boundary between County Antrim and County Down. First laid out in the 17th century by English and Welsh settlers, with t ...

and Banbridge

Banbridge ( ) is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies on the River Bann and the A1 road and is named after a bridge built over the Bann in 1712. It is in the civil parish of Seapatrick and the historic barony of Iveagh Upper ...

.

Conflict continued intermittently for two years, mostly in Belfast, which saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence

Communal violence is a form of violence that is perpetrated across ethnic or communal lines, where the violent parties feel solidarity for their respective groups and victims are chosen based upon group membership. The term includes conflicts, ri ...

between Protestants and Catholics. Almost 1,000 homes and businesses were destroyed and thousands of people were forced out of mixed neighborhoods. The British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

was deployed and the Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military Military reserve, reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, short ...

(USC) (or Specials) were formed to help the regular police – the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the island was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom. A sep ...

(RIC). The USC was almost wholly Protestant. Members of both police forces were involved in carrying out reprisal attacks on Catholics. The self-declared Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( or ) was a Revolutionary republic, revolutionary state that Irish Declaration of Independence, declared its independence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdict ...

approved the 'Belfast Boycott' of unionist-owned businesses and banks in the city. It was enforced by the IRA, who halted trains and lorries and destroyed goods.

In May 1921, the Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 5. c. 67) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bi ...

came into force, dividing the island between two administrations: Southern Ireland (consisting of the 26 southern and western counties, including three Ulster counties) and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

(consisting of the remaining six counties of the province). A truce between the beligerents began on 11 July 1921, ending the fighting in most of Ireland. It was preceded by Belfast's Bloody Sunday, a day of violence in which twenty people were killed. In early 1922, there was a resurgence of sectarian violence in Belfast, including the McMahon killings

The McMahon killings or the McMahon murders occurred on 24 March 1922 when six Catholic civilians were shot dead at the home of the McMahon family in Belfast, Northern Ireland. A group of police officers broke into their house at night and sho ...

and the Arnon Street killings

The Arnon Street killings, also referred to as the Arnon Street murders or the Arnon Street massacre, took place on 1 April 1922 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Six Roman Catholicism, Catholic civilian men and boys, three in Arnon Street, were s ...

. In May 1922 the IRA launched their Northern Offensive. There were clashes near the new Irish border

Irish commonly refers to:

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the island and the sovereign state

***Erse (disambiguatio ...

, at Clones and the Pettigo

Pettigo, also spelt Pettigoe ( ; ), is a small village and townland on the border of County Donegal, Republic of Ireland, and County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It is bisected by the Termon River, which is part of the border between the Repu ...

/ Belleek area. Also in May 1922, the new government of Northern Ireland implemented the Special Powers Act (also known as the "Flogging Act"), interning suspected IRA members, and imposing a nighttime curfew across the six counties of Northern Ireland. The outbreak of the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

in the south on 28 June 1922 diverted the IRA from its campaign against the Northern government, and violence in Northern Ireland fell sharply.

Background

In the early 20th century, all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. A majority of Ireland's people were

In the early 20th century, all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. A majority of Ireland's people were Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

and Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

who wanted either self-government ("home rule

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governan ...

") or independence. However, in the north-east of Ireland, Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and Unionists were the majority, largely as a result of the 17th century colonization of the northern province of Ulster - the Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster (; Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster Scots: ) was the organised Settler colonialism, colonisation (''Plantation (settlement or colony), plantation'') of Ulstera Provinces of Ireland, province of Irelandby people from Great ...

. Home Rule for Ireland had been an issue for many years – in 1886 the first Home Rule Bill

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to ...

was introduced in the British House of Parliament. Ulster Unionists resisted that Bill with violence – 31 to 50 people were killed in ongoing riots during June/July 1886 (see the 1886 Belfast riots

The 1886 Belfast riots were a series of intense riots that occurred in Belfast, Ireland, during the summer and autumn of 1886.

Background

In the late 19th century, Catholics began to migrate in large numbers to the prosperous city of Belfast i ...

). The second Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1893, much violence ensued with Catholic workmen being driven from their jobs in the Belfast shipyards. Riots occurred on a regular basis in Belfast during the 19th century, as far back as 1815. Serious rioting took place in 1835 (two rioters shot dead), 1841, 1843, 1857, 1864, 1872, 1880,1884 and 1898. In 1912 Belfast was the scene of "fullscale sectarian rioting" which caused further segregation between the Catholic and Protestant communities.

Home rule for all of Ireland was set to take place with the Government of Ireland Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 ( 4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-gover ...

(Home Rule Act). During the Home Rule Crisis

The Home Rule Crisis was a political and military crisis in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that followed the introduction of the Government of Ireland Act 1914, Third Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom ...

of 1912–14, Unionists threatened to oppose any Irish government with violence if necessary, forming a paramilitary group: the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

or Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group based in Northern Ireland. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former Royal Ulster Rifles soldier from North ...

(UVF) and arming themselves (see Larne gun-running

The Larne gun-running was a major gun smuggling operation organised in April 1914 in Ireland by Major Frederick H. Crawford and Captain Wilfrid Spender for the Ulster Unionist Council to equip the Ulster Volunteer Force. The operation involve ...

). On 20 March 1914, the Curragh Mutiny

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the U ...

occurred in which British Army officers vowed to resign or be dismissed if they were ordered to enforce the Home Rule Act. Ulster unionists argued that if Home Rule could not be stopped, then all or part of Ulster should be excluded from it (see Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 5. c. 67) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bi ...

). The Act divided Ireland along established county lines (see Partition of Ireland

The Partition of Ireland () was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland (the area today known as the R ...

), creating two self-governing

Self-governance, self-government, self-sovereignty or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any ...

territories within the United Kingdom: Northern Ireland (with Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

as its capital) and Southern Ireland (1921–22)

Southern Ireland, South Ireland or South of Ireland may refer to:

*The southern part of the island of Ireland

**Munster, a traditional province of Ireland

*Republic of Ireland, which is sometimes inaccurately referred to as "Southern Ireland"

* ...

(with Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

as its capital). Six of the nine counties in the province of Ulster – Antrim, Down, Armagh

Armagh ( ; , , " Macha's height") is a city and the county town of County Armagh, in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Primates of All ...

, Londonderry, Tyrone and Fermanagh

Historically, Fermanagh (), as opposed to the modern County Fermanagh, was a kingdom of Gaelic Ireland, associated geographically with present-day County Fermanagh. ''Fir Manach'' originally referred to a distinct kin group of alleged Laigin or ...

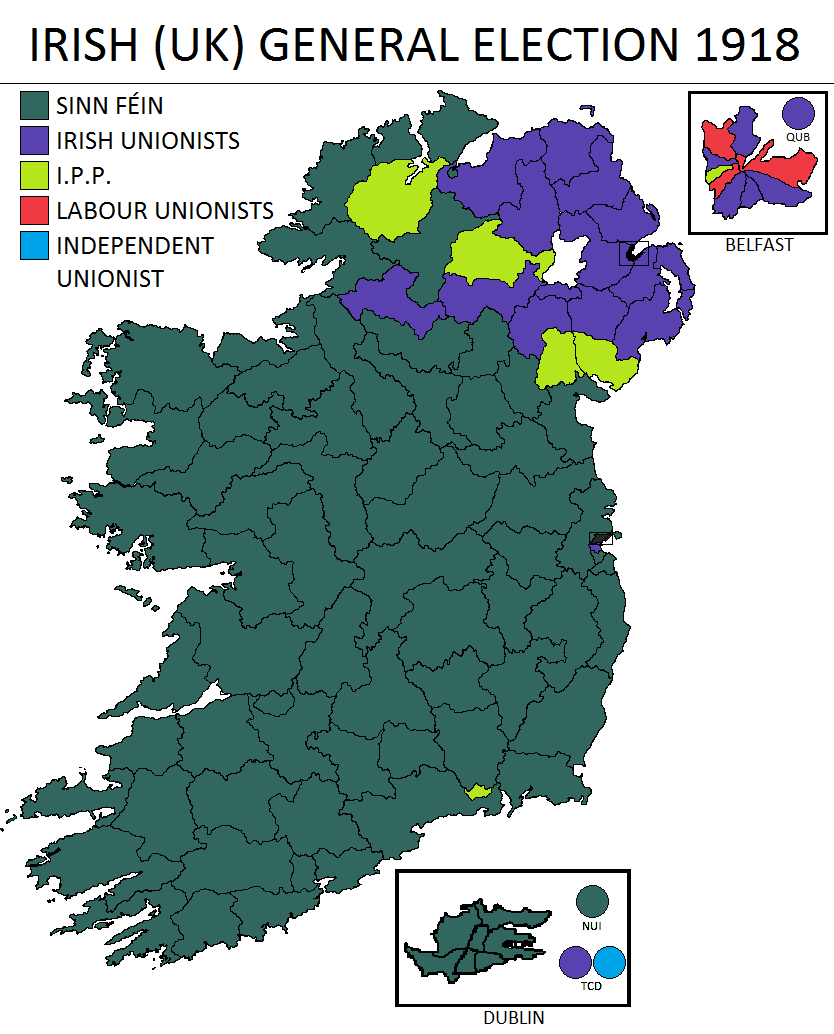

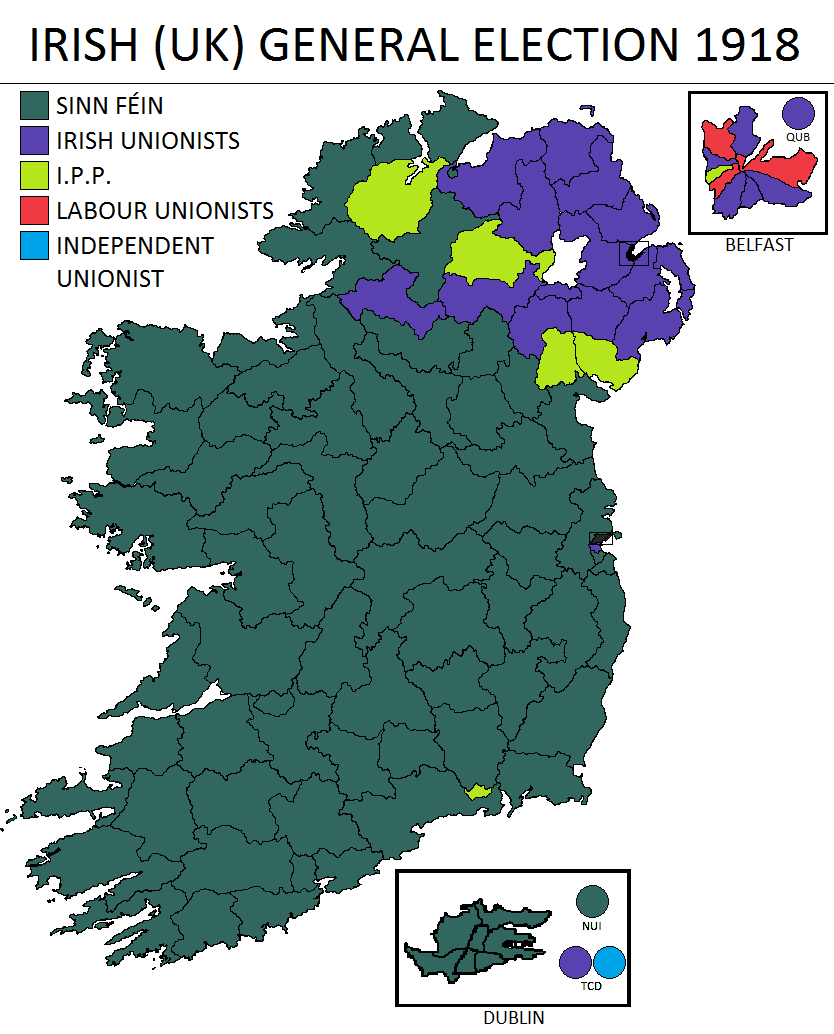

comprised the maximum area Unionists believed they could dominate. Generally, Irish nationalists opposed partition, in the 1918 Irish general election

The Irish component of the 1918 United Kingdom general election took place on 14 December 1918. It was the final United Kingdom general election to be held throughout Ireland, as the next election would happen following Irish independence. It is ...

five of the nine Counties of Ulster returned Irish republican

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

party Sinn Fein

In the philosophy of language, the distinction between sense and reference was an idea of the German philosopher and mathematician Gottlob Frege in 1892 (in his paper "On Sense and Reference"; German: "Über Sinn und Bedeutung"), reflecting the ...

and Irish nationalist (Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

) majorities. Although Counties Fermanagh and Tyrone returns showed nationalist majorities, they were included into Northern Ireland.

By the end of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

(during which the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

had taken place), most Irish nationalists now wanted full independence rather than home rule. In the last general election to be held throughout Ireland (the 1918 Irish general election) Sinn Féin won the overwhelming majority of Irish seats. In line with its manifesto, Sinn Féin's elected members boycotted the British parliament and founded a separate Irish parliament (Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( ; , ) is the lower house and principal chamber of the Oireachtas, which also includes the president of Ireland and a senate called Seanad Éireann.Article 15.1.2° of the Constitution of Ireland reads: "The Oireachtas shall co ...

), declaring the establishment of an independent Irish Republic covering the whole island. However, Unionists won the most seats in the area that became Northern Ireland and affirmed their continuing loyalty to the United Kingdom. Many Irish republicans blamed the British establishment for the sectarian divisions in Ireland, and believed that Ulster Unionist defiance would fade after British rule was ended. The British authorities outlawed the Dáil in September 1919, and a guerrilla conflict developed as the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922)

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ) was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican revolutionary paramilitary organisation who waged a Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla campaign against the British occupation of Ireland in the 1919–1921 Irish War of In ...

began to attack British forces. This conflict became known as the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

.

Another contributing factor to the outbreak of communal violence was the severe economic recession that followed the end of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Many workers were made redundant, working hours were reduced and many returning soldiers were unable to find work. Some returning Protestant soldiers felt bitterness against the many Catholics who had remained at home and now held jobs. At the same time, fiery political speeches were made by Unionist leaders and weapons were stockpiled by Ulster loyalists and Irish nationalists. Other events which contributed to the outbreak of violence were the assassinations of senior British Army officers, policemen and politicians: RIC Divisional Commissioner Lt Col Gerald Smyth (July 1920), RIC District Inspector Swanzy (August 1920), Belfast City Councilman William J. Twaddell (May 1922), and British Army Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, 1st Baronet, (5 May 1864 – 22 June 1922) was one of the most senior British Army staff officers of the First World War and was briefly an Unionism in Ireland, Irish unio ...

(the Military Advisor to the Ulster Government). IRA volunteers Reginald Dunne

Reginald William Dunne (June 1898 – 10 August 1922) was Battalion Commandant of the London Battalion, IRA and one of two men hanged for the murder of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson.

Dunne, the only child of Robert and Mary Dunne, was born (as ...

and Joseph O'Sullivan

Joseph O'Sullivan (25 January 1897 – 10 August 1922), along with fellow Irish Republican Army (IRA) (London Battalion) volunteer Reginald Dunne, shot dead Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson outside Wilson's home at 36 Eaton Place, Belgravia, Lo ...

(both of whom had served as British soldiers in World War I) were apprehended

and found guilty of Wilson's murder. They were hanged on 10 August 1922.

In June 1920, the Ulster Unionist Council

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded as the Ulster Unionist Council in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist oppositi ...

remobilized the UVF with one of the leading organizers being the future, long term Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The prime minister of Northern Ireland was the head of the Government of Northern Ireland (1921–1972), Government of Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972. No such office was provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920; however, the L ...

, Basil Brooke (1943–1963). In 1920, the Commander in Chief in Ireland, Nevil Macready

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Cecil Frederick Nevil Macready, 1st Baronet, (7 May 1862 – 9 January 1946), known affectionately as Make-Ready (close to the correct pronunciation of his name), was a British Army officer. He served in ...

, warned against a rearmed UVF that "would undoubtedly consist entirely of Protestants, and no amount of so called loyalty is likely to restrain them if the religious question becomes acute...the arming of the Protestant population of Ulster will mean the outbreak of civil war in this country, as distinct from the attempted suppression of rebellion with which we are engaged at present." The British Prime Minister, Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, had around the same time formed the Black and Tans

The Black and Tans () were constables recruited into the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as reinforcements during the Irish War of Independence. Recruitment began in Great Britain in January 1920, and about 10,000 men enlisted during the conflic ...

and Auxiliary Division

The Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary (ADRIC), generally known as the Auxiliaries or Auxies, was a paramilitary unit of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the Irish War of Independence. It was founded in July 1920 by Majo ...

made up of returning soldiers to help bolster the RIC, but they quickly became notorious for their actions against nationalists.

Sectarian strife

As the Irish War of Independence spread northwards into Ulster, sectarian clashes took place, which would spark a period of fierce sectarian fighting that overshadowed all the riots and clashes of the preceding century. In January 1920,local elections

Local may refer to:

Geography and transportation

* Local (train), a train serving local traffic demand

* Local, Missouri, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Local'' (comics), a limited series comic book by Bria ...

took place for the first time with the single transferable vote

The single transferable vote (STV) or proportional-ranked choice voting (P-RCV) is a multi-winner electoral system in which each voter casts a single vote in the form of a ranked ballot. Voters have the option to rank candidates, and their vot ...

form of proportional representation. The British Prime Minister had hoped that this system would show a lack of support for Sinn Féin, and this view had vindication after Sinn Féin won only 550 seats compared to 1,256 for all the other parties, including the Nationalist Party. However, Unionists became dismayed when an electoral pact saw Sinn Féin and the Nationalist Party gaining control of ten urban councils within the area due to become Northern Ireland. In Derry, Alderman Hugh O'Doherty

Hugh O'Doherty (died 10 March 1924) was an Irish nationalist politician.

O'Doherty worked as a solicitor in County Londonderry. A supporter of Charles Stewart Parnell, he was a founder member of the Irish National League. Following Parnell's deat ...

became the first Catholic mayor of the city. His inaugural speech did little to allay the fears of the unionist population of the city: "Ireland's right to determine her own destiny will come about whether the Protestants of Ulster like it or not".Bardon, pp. 466–469 Irish nationalist newspaper the ''Derry Journal

The ''Derry Journal'' is a newspaper based in Derry, Northern Ireland, serving Derry as well as County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland. It is operated by National World. The paper is published on Tuesday and Friday and is a sister paper of ...

'' heralded the fall of unionist control over Londonderry Corporation, declaring "No Surrender – Citadel Conquered". In another local election in June 1920, thirteen rural councils in Ulster came under joint Nationalist-Sinn Féin control, as did Tyrone and Fermanagh

Historically, Fermanagh (), as opposed to the modern County Fermanagh, was a kingdom of Gaelic Ireland, associated geographically with present-day County Fermanagh. ''Fir Manach'' originally referred to a distinct kin group of alleged Laigin or ...

county councils. Unionist representation in Belfast fell from 52 to 29 as a result of the good showing of the Belfast Labour Party

The Belfast Labour Party was a political party in Belfast, Ireland from 1892 until 1924.

It was founded in 1892 by a conference of Belfast Independent Labour Party, Independent Labour activists and trade unionists.

Labour ran the Ulster Unionis ...

. These events and the nationalist triumphalism that came with them encouraged their hopes that partition would be ditched, whilst compounding the feeling of abandonment amongst unionists, especially in Derry.

Troubles

Derry 1920

Sectarian strife began in Derry in April 1920 when an hour-long violent confrontation between Protestants and Catholics erupted on Long Tower Street, as republican prisoners were being transported to Bishop Street gaol. On the 18th of April, shots were fired into theBogside

The Bogside is a neighbourhood outside the city walls of Derry, Northern Ireland. The large gable-wall murals by the Bogside Artists, Free Derry Corner and the Gasyard Féile (an annual music and arts festival held in a former gasyard) are ...

as Catholics rioted in the city center, the RIC carried out a bayonet charge. On 14 May more trouble ensued as the RIC and IRA engaged in a four-hour gun battle, which resulted in the shooting death of the local chief of the RIC Special Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and Intelligence (information gathering), intelligence in Policing in the United Kingdom, British, Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, ...

. In response, loyalists reformed the UVF in the city and mounted roadblocks, Catholics crossing Carlisle Bridge were mistreated, resulting in one who had returned injured from the war being killed. On 13 June, the UVF attacked Catholics at Prehen Wood, which sparked intense rioting in the city, where Long Tower Street and Bishop Street met.

The violence that broke out in Derry continued for a week in June 1920. At least nineteen people were killed or fatally wounded during this time: 14 Catholics and five Protestants.Eunan O'Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin (2020). ''The Dead of the Irish Revolution''. Yale University Press, pp. 141–145 On 18 June, rioting had spread into the mainly-Protestant Waterside area of the city, where Catholic homes were burnt. The UVF, with the aid of ex-servicemen, seized control of the Guildhall

A guildhall, also known as a guild hall or guild house, is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Europe, with many surviving today in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commo ...

and Diamond, whilst also repulsing an IRA counter-attack. Protestants living in the mainly-Catholic Bogside would be burnt out of their houses by the IRA, with two shot dead. Loyalists fired from the Fountain neighborhood into adjoining Catholic streets. The IRA, armed with rifles and machine-guns, occupied St Columb's College

St Columb's College is a Roman Catholic boys' grammar school in Derry, Northern Ireland. Since 2008, it has been a specialist school in mathematics. It is named after Saint Columba, the missionary monk from County Donegal who founded a monast ...

, which became the scene of intense gunfire.

Eventually, on 23 June 1920, 1,500 British troops arrived in Derry to restore order, martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

was declared in the city, and a destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

was anchored on the Foyle overlooking the Guildhall. The presence of the military did little to stifle the violence as riots, shootings, and assassinations continued. Six people (four Catholics, two Protestants) were killed in the last week of June, after the army's deployment. According to some sources, six Catholics were killed in the Bogside by heavy machine gun

A heavy machine gun (HMG) is significantly larger than light, medium or general-purpose machine guns. HMGs are typically too heavy to be man-portable (carried by one person) and require mounting onto a weapons platform to be operably stable or ...

fire from soldiers. By the end of this period of trouble forty people had been killed.

Older Belfast shipyard worker "clearances"

The large-scale violence of July 1920 - June 1922 was preceded by similar actions in June 1898 and July 1912. The 1898, 1912 and 1920 "clearances" were made all of Catholic shipyard workers,Socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

and Protestant trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

ists. In the 1898 "clearances", approximately 700 Catholic workers were driven from shipyards, linen mills and other businesses where Protestants were in the majority. The 1912 clearances resulted in many assaults with thousands of Catholics and Protestant being forcibly removed from their jobs. The events that triggered the 1912 workplace expulsions were the introduction of the Home Rule for Ireland Act in April 1912 and another incident which took place in Castledawson

Castledawson is a village in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It is mostly within the townland of Shanemullagh (, IPA: �anˠˈʃanˠˌwʊl̪ˠəx, about four miles from the north-western shore of Lough Neagh, and near the market town of Mag ...

, County Londonderry when a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is in the United States, where it was founded in New Yo ...

snatched a British flag from the hands of a young boy – resulting in rioting. When the news spread to Belfast 2,400 Catholics and some 600 Protestant trade unionists were driven (often violently) from their places of work. In the 1912 violence, the directors of Harland and Wolff

Harland & Wolff Holdings plc is a British shipbuilding and Metal fabrication, fabrication company headquartered in London with sites in Belfast, Arnish yard, Arnish, Appledore, Torridge, Appledore and Methil. It specialises in ship repair, ship ...

shipyards decided to suspend operations "in view of the brutal assaults on individual workmen and the intimidation of others.".

Belfast Pogrom

OnThe Twelfth

The Twelfth (also called Orangemens' Day) is a primarily Ulster Protestant celebration held on 12 July. It began in the late 18th century in Ulster. It celebrates the Glorious Revolution (1688) and victory of Protestant King William of Ora ...

(12 July) 1920 (an annual Ulster Protestant celebration), Ulster Unionist Party leader Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, Baron Carson, Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC, Privy Council of Ireland, PC (Ire), King's Counsel, KC (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician ...

made a speech to thousands of Orangemen in Finaghy

Finaghy (

or ; ) is an electoral ward in the Balmoral district of Belfast City Council, Northern Ireland. It is based on the townland of Ballyfinaghy (). There has been a small community living in the area since the 17th century, and it has bee ...

, near Belfast. He said "I am sick of words without actions" and he warned the British government that if it refused to adequately protect Unionists from the IRA, they would take matters into their own hands.Magill, p. 42 He also linked Irish republicanism with socialism and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. Many Catholics asserted that Carson's rhetoric was partly responsible for the start of what they believed was a pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

being carried out against Belfast's Catholic minority, referring to it as the ''Belfast Pogrom''. At this time in Belfast, Catholics made up a quarter of the city's population but accounted for up two-thirds of those killed, they suffered 80% of the property destruction and comprised 80% of refugees. Despite the roles played by state forces, particularly the USC, most unionist historians say the term "pogrom" is misleading, claiming the police violence was not co-ordinated.

On 21 July 1920, when shipyard workers returned after the Twelfth holidays, a meeting of "all Unionist and Protestant workers" was called during lunch hour that day by the Belfast Protestant Association

{{Use dmy dates, date=April 2022

The Belfast Protestant Association was a populist evangelical political movement in the early 20th-century.

The Association was founded in the last years of the 19th century by Arthur Trew, a former shipyard worker ...

at the Workman and Clarke yard. With over 5,000 workers present, speeches were made, demanding the expulsion of all "non-loyal" workers. Hours of intimidation and violence followed, in which Loyalists drove 8,000 co-workers from Harland and Wolff other shipyards, industrial sites and several linen mills. All of the removed workers were either Catholics or Protestant labour activists. Some of them were beaten,Lynch (2019), pp. 92–93 or thrown into the water and pelted with rivets as they swam for their lives. Three days of rioting followed, in which eleven Catholics and eight Protestants were killed and hundreds of people were wounded.

Around the Falls-Shankill interface

Interface or interfacing may refer to:

Academic journals

* ''Interface'' (journal), by the Electrochemical Society

* '' Interface, Journal of Applied Linguistics'', now merged with ''ITL International Journal of Applied Linguistics''

* '' Inter ...

, seven Catholics and two Protestants were killed, mostly by soldiers who were attempting to disperse rioters in the area.O'Halpin & Ó Corráin, pp. 151–153 Several of those killed were ex-servicemen

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in an occupation or field.

A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in the armed forces.

A topic of interest for resea ...

and one was a Redemptorist

The Redemptorists, officially named the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (), abbreviated CSsR, is a Catholic clerical religious congregation of pontifical right for men (priests and brothers). It was founded by Alphonsus Liguori at Scal ...

friar who was shot by a bullet fired from a passing military patrol through a window of Clonard Monastery

Clonard Monastery is a Catholic church located off the Falls Road (Belfast), Falls Road in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and home to a community of the Redemptorists Religious order (Catholic), religious order.

History

In late 19th century Belfast, ...

. A Loyalist mob attempted to burn down a Catholic convent

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

on Newtownards Road; soldiers guarding the building responded opened fire, wounding 15 Protestants, three of them fatally.

At other workplaces in Belfast, expulsions continued for several days, and those expelled included several hundred female textile workers. Catholics and Socialists were driven out of other large firms such as Mackies Foundry and Sirocco Engineering Works. According to the Catholic Protection Committee, 11,000 Catholic shipyard, factory and mill workers had been expelled from their jobs, a tenth of Belfast's Catholic population. The leader of the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded as the Ulster Unionist Council in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it l ...

and the soon to be Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The prime minister of Northern Ireland was the head of the Government of Northern Ireland (1921–1972), Government of Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972. No such office was provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920; however, the L ...

, Sir James Craig, made his feelings on the expulsions clear when he visited the shipyards: "Do I approve of the actions you boys have taken in the past? I say yes".

By August 1920 Catholics were no longer employed in the shipyards and material damage valued at one half million pounds had been done. The expulsion of thousands of Catholic workers from the shipyards and other Belfast workplaces were followed by retaliatory attacks against Protestant workers as they were returning home from work, starting a cycle of communal violence which continued for over two years. One of the more brutal attacks on returning workers occurred on 22 November 1921 when bombs were thrown into a tram carrying workers from the Workman, Clark and Co. shipyard – three workers were killed and 16 wounded.

The now unemployed Catholic shipyard workers continued their attacks on Protestants as they returned home after work. In late November 1921 multiple trams carrying shipyard workers were attacked, killing eight Protestant workers. Loyalist retaliation resulted in fifteen Nationalists killed in one day alone (22 November 1921). St. Matthew's church in the Catholic enclave of Ballymacarrett

Ballymacarrett or Ballymacarret () is the name of both a townland and electoral ward in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The townland is in the civil parish of Knockbreda (civil parish), Knockbreda in the historic barony (Ireland), barony of Castler ...

came under sustained attack and in March 1922, nearby St Matthew's Primary School was also subjected to a bombing attack.

Peace lines

In the 1920s, temporary

In the 1920s, temporary Peace lines

The peace lines or peace walls are a series of separation barriers in Northern Ireland that separate predominantly Irish republican or nationalist Catholic neighbourhoods from predominantly British loyalist or unionist Protestant neigh ...

(walls) were built in the area adjacent to the Harland & Wolff

Harland & Wolff Holdings plc is a British shipbuilding and Metal fabrication, fabrication company headquartered in London with sites in Belfast, Arnish yard, Arnish, Appledore, Torridge, Appledore and Methil. It specialises in ship repair, ship ...

shipyards in Belfast and made permanent in 1969, following the outbreak of the 1969 Northern Ireland riots

During 12–16 August 1969, there was an outbreak of political and sectarian violence throughout Northern Ireland, which is often seen as the beginning of the thirty-year conflict known as the Troubles. There had been sporadic violence throug ...

. Today, the Ballymacarrett

Ballymacarrett or Ballymacarret () is the name of both a townland and electoral ward in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The townland is in the civil parish of Knockbreda (civil parish), Knockbreda in the historic barony (Ireland), barony of Castler ...

/Short Strand

The Short Strand () is a working class, inner city area of Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is a mainly Catholic and Irish nationalist enclave surrounded by the mainly Protestant and unionist East Belfast.

Short Strand is located on the east ban ...

areas of Belfast remain basically segregated and violence still occurs. The Battle of St Matthew's

The Battle of St Matthew's or Battle of Short Strand was a gun battle that took place on the night of 27–28 June 1970 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It was fought between the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), and Ulster loyalists in ...

or Battle of Short Strand was a gun battle that took place on the night of 27–28 June 1970 resulting in three deaths and at least 26 wounded. Major sectarian clashes were common in the shipyard area into the 21st century – 2002 Short Strand clashes

The 2002 Short Strand clashes, also known as the siege of Short Strand, was a series of major sectarian violence and gun battles in and around the Short Strand area of east Belfast – a mainly Irish/Catholic enclave surrounded by Protestant co ...

and 2011 Northern Ireland riots

The 2011 Northern Ireland riots were a series of riots between 20 June 2011 and 16 July 2011, starting originally in Belfast, before spreading to other parts of Northern Ireland. They were initiated by the Ulster Volunteer Force.

June riots

The ...

.

Belfast boycott

In response to the expulsions of Catholic workers in Belfast and requirements for employment (political loyalty tests and the requirement to sign loyalty declarations to the British Government), northern Sinn Féin members called for the

In response to the expulsions of Catholic workers in Belfast and requirements for employment (political loyalty tests and the requirement to sign loyalty declarations to the British Government), northern Sinn Féin members called for the boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

of Unionist-owned businesses and banks in the city.Lawlor, ''The Burnings'', p. 184 Despite some opposition, the Dáil and its cabinet approved the boycott in August 1920, imposing a boycott of goods from Belfast and a withdrawal of funds from Belfast-based banks. In January 1921, the Dáil agreed to support the boycott more fully, providing 35,000 pounds to the campaign. Joseph MacDonagh

Joseph Michael MacDonagh (18 May 1883 – 25 December 1922) was an Irish Sinn Féin politician.

He was born in Cloughjordan, County Tipperary. His parents Joseph MacDonagh and Mary Parker were both national schoolteachers. His brothers includ ...

(brother of executed 1916 Easter Rising leader Thomas MacDonagh

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh (; 1 February 1878 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish political activist, poet, playwright, educationalist and revolutionary leader. He was one of the seven leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916, a signatory of the Proclama ...

) oversaw the implementation of the boycott, by May 1921 there were 360 Belfast Boycott committees throughout Ireland, but it was enforced intermittently.

The boycott was enforced by the IRA, who halted trains and lorries and destroyed goods from Belfast businesses. The female members of Cumann na mBan

Cumann na mBan (; but in English termed The Irishwomen's Council), abbreviated C na mB, is an Irish republican women's paramilitary organisation formed in Dublin on 2 April 1914, merging with and dissolving Inghinidhe na hÉireann, and in 191 ...

played major roles in holding up trains and the seizure/destruction of northern produced goods/Unionist leaning newspapers. Eithne Coyle

Eithne Coyle (1897–1985; ) was an Irish republican activist. She was a leading figure within Cumann na mBan ( women's paramilitary organisation) and a member of the Gaelic League.Cal McCarthy, ''Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution'', T ...

held up several trains bound from County Tyrone to County Donegal. However, the boycott was effectively enforced only in County Monaghan

County Monaghan ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is part of Border Region, Border strategic planning area of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town ...

, primarily due to its location near the newly-proclaimed border and Belfast. The following declaration was signed by all of Monaghan's Catholic commercial traders: "We the undersigned traders of Monaghan town, hereby pledge ourselves not to deal directly or indirectly with Belfast Unionist firms or traders until such time as adequate reparation has been made to the Catholic victims of the recent Belfast pogrom".

The boycott had little impact on the north's three main industriesagriculture, shipbuilding and linenas they were mainly shipped to markets outside Ireland. In March 1922, the Craig- Collins pact had both leaders agree that Craig would try to have Catholic workers regain the jobs lost in the shipyard clearances of 1920. Collins agreed to end IRA actions against the police and military in the six counties and to end the boycott. The Belfast Boycott eventually ended following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

of December 1921 and the onset of the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

(June 1922 – May 1923).

Banbridge and Dromore burnings

On 17 July 1920, the IRA assassinated British Colonel Gerald Smyth inCork

"Cork" or "CORK" may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Stopper (plug), or "cork", a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

*** Wine cork an item to seal or reseal wine

Places Ireland

* ...

. He had told police officers to shoot civilians who did not immediately obey orders.Lawlor, Pearse. ''The Burnings, 1920''. Mercier Press, 2009. pp. 67–77 Smyth was from a wealthy Protestant family in the northern town of Banbridge

Banbridge ( ) is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies on the River Bann and the A1 road and is named after a bridge built over the Bann in 1712. It is in the civil parish of Seapatrick and the historic barony of Iveagh Upper ...

, County Down and his large funeral was held there on 21 July, the same day as the Belfast shipyard expulsions. After Smyth's funeral, about 3,000 Loyalists took to the streets. Many Catholic homes and businesses were attacked, burned and looted, despite police being present. A large mob of Loyalists, some armed, attacked and tried to break into the home of a republican family. The father fired on the crowd, killing a Protestant man. Hundreds of Catholic factory workers were also driven from their jobs, and many Catholic families fled Banbridge. Calm was restored after the British Army was deployed into the town.

On 23 July 1920, sectarian motivated riots occurred in Dromore, County Down

Dromore () is a small market town and civil parish in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies within the local government district of Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon. It is southwest of Belfast, on the A1 Belfast–Dublin road. The 2011 ...

. An estimated crowd of 500 attacked Catholic homes, the Catholic parochial house and looted businesses. During the rioting, one member of the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

was shot dead, it was determined that the bullet had been fired by the police trying to disperse the mob. At the end of these two days of violence, virtually the entire Catholic population of both Banbridge and Dromore were forced to flee their homes. Sectarian intimidation and violence continued in Banbridge and areas north of the town (the Bann Valley) throughout August and September 1920 with approximately 1,000 more Catholics being expelled from their jobs.

Lisburn burnings and Belfast Violence

Sectarian attacks also occurred in

Sectarian attacks also occurred in Lisburn

Lisburn ( ; ) is a city in Northern Ireland. It is southwest of Belfast city centre, on the River Lagan, which forms the boundary between County Antrim and County Down. First laid out in the 17th century by English and Welsh settlers, with t ...

, County Antrim (a town near Belfast) in response to the murder of Colonel Smyth. On 24 July 1920 rioters attacked Catholic owned businesses, homes and the Catholic convent of the Sacred Heart.

On 22 August 1920, the IRA assassinated RIC Inspector Oswald Swanzy in the Market Square of Lisburn, as worshippers left Sunday service. A coroner's inquest in Cork had held Swanzy (among others) responsible for the murder of Tomás Mac Curtain

Tomás Mac Curtain (20 March 1884 – 20 March 1920) was an Irish Sinn Féin politician who served as the Lord Mayor of Cork until he was assassinated by the Royal Irish Constabulary. He was elected in January 1920.

Background

Tomás Mac Curt ...

, Cork's Irish republican Lord Mayor

Lord mayor is a title of a mayor of what is usually a major city in a Commonwealth realm, with special recognition bestowed by the sovereign. However, the title or an equivalent is present in other countries, including forms such as "high mayor". A ...

. The commander of Belfast IRA 1st Battalion Joe McKelvey

Joseph McKelvey (17 June 1898 – 8 December 1922) was an Irish Republican Army officer who was executed during the Irish Civil War without trial or court martial. He participated in the Anti-Treaty IRA's repudiation of the authority of the D ...

helped to organize the attack on Swanzy (the killers were IRA men from Cork).

Over the next three days and nights (in attacks likened to ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

), Loyalist crowds looted and burned almost every Catholic business in the town, and attacked Catholic homes.Lawlor, ''The Burnings'', pp. 115–121 There is evidence the UVF helped organise the burnings. Rioters attacked firemen who tried to save Catholic property, and attacked the lorries of British soldiers sent to help the police. A Catholic pub owner later died of gunshot wounds and a charred body was found in the ruins of a factory.

Lisburn was likened to "a bombarded town in France" during the First World War. A third of the town's Catholics (about 1,000 people) fled Lisburn. The attacks in Lisburn, Dromore and Banbridge led to a long-term decline of the Catholic populations of those towns. Damage in Lisburn was estimated at 810,000 pounds (in 1920 currency). Seven men were arrested and charged with rioting – five were convicted but appealed their convictions and were released.

''Daily News'' correspondent Hugh Martin was quoted on the attacks in Lisburn and Banbridge: "This was no mere faction fight. There can be no doubt that it was a deliberate and organised attempt to, not by any means the first in history, to drive the Catholic Irish out of North-East Ulster."

During the last weekend of August 1920 sectarian violence was also widespread in nearby Belfast. The Belfast Telegraph

The ''Belfast Telegraph'' is a daily newspaper published in Belfast, Northern Ireland, by Independent News & Media, which also publishes the Irish Independent, the Sunday Independent and various other newspapers and magazines in Ireland. Its e ...

newspaper reported 17 people dead and over 169 seriously wounded. Within four days of the killing of District Inspector Swanzy in Lisburn at least 100 homes of Nationalists were burned in Belfast. Between August 1920 and April 1922 at least four large scale clashes occurred in the small Belfast Nationalist enclave known as Marrowbone (adjacent to Ardoyne

Ardoyne () is a working class and mainly Roman Catholic Church, Catholic and Irish republicanism, Irish republican district in north Belfast, Northern Ireland. In 1920 the adjacent area of Marrowbone saw at multiple days of communal violence be ...

). Initially crowds of armed Unionists attempted to burn the local Catholic church. During this time approximately 20 residents of the Marrowbone and rioters were killed (six Nationalists were killed in Marrowbone on 28 August 1920), dozens of people were wounded, and multiple homes burned.

Forming the Ulster Special Constabulary

In September 1920, Unionist leaderJames Craig James or Jim Craig may refer to:

Entertainment

* James Humbert Craig (1877–1944), Irish painter

* James Craig (actor) (1912–1985), American actor

* James Craig (''General Hospital''), fictional character on television, a.k.a. Jerry Jacks

* J ...

wrote to the British government demanding that a special constabulary

The Special Constabulary is the part-time volunteer section of statutory police forces in the United Kingdom and some Crown dependencies. Its officers are known as special constables.

Every United Kingdom territorial police force has a speci ...

be recruited from the ranks of the loyalist, paramilitary organization the UVF. He warned: "Loyalist leaders now feel the situation is so desperate that unless the Government will take immediate action, it may be advisable for them to see what steps can be taken towards a system of organized reprisals against the rebels".Hopkinson, ''Irish War of Independence'', p. 158 The Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military Military reserve, reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, short ...

(USC), commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men" was formed in October 1920 and, in the words of historian Michael Hopkinson, "amounted to an officially approved UVF". Irish nationalists saw the founding of this almost wholly Protestant force as the arming of the majority against the Catholic minority.

In late October 1920, Joe Devlin, the MP for West Belfast voiced his opinion on the impartiality of the newly formed USC:

The USC consisted of 32,000 men divided into four sections: A Specials were fulltime and paid. B Specials were part time and unpaid and the C Specials were unpaid and nonuniform reservists. Under the terms of the Truce between the IRA and the British (11 July 1921), the USC was demobilized, and the IRA was given official recognition while peace talks were ongoing. Although the Truce forbade both sides from forming any new military units, by November 1921 a new Unionist organization was formed - the Imperial Guards. With a claim of 21,000 members, their goal was to have 150,000 members within a few months. The Imperial Guards were closely associated with the Ulster Unionist Labour Association

The Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA) was an association of trade unionists founded by Edward Carson in June 1918, aligned with the Ulster Unionists in Ireland. Members were known as Labour Unionists. In Britain, 1918 and 1919 were marke ...

and the Ulster Ex-servicemen's Association with many of their membership coming from Belfast shipyard workers. By the fall of 1922 most members of the Imperial Guards had been integrated into the C Specials. After policing became the responsibility of the newly formed Northern government, the B Specials of the USC were again mobilized. Maintaining the USC was costly, in fiscal year 1922-1923 the British Treasury allocated £850,000 to cover the cost of the USC but the costs of additional vehicles and armaments brought the final figure to £1,829,000. The USC or "Specials" were used in every decade of the 20th century up to its disbandment in May 1970.

Spring and summer 1921

After a lull, the conflict in the north intensified again in the spring of 1921. On 1 April, the IRA attacked an RIC barracks and a British Army post in Derry city with gunfire and grenades, killing two RIC officers.Lawlor, ''The Outrages'', pp.146–148 On 10 April, the IRA ambushed a group of Special Constables outside a church inCreggan, County Armagh

Creggan () is a small village, townland and civil parish near Crossmaglen in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. In the 2001 Census it had a population of 246 people. It lies within the Newry and Mourne District Council area.

Places of interest ...

, killing one and wounding others. In reprisal, the USC attacked nationalists and burned their houses in Killylea

Killylea (; ) is a small village and townland in Northern Ireland. It is within the Armagh City and District Council area. The village is set on a hill, with St Mark's Church of Ireland, built in 1832, at its summit. The village lies to th ...

(where the dead Special Constables came from). On 10 June, the IRA shot three RIC officers on Belfast's Falls Road, fatally wounding Constable James Glover. He had been targeted because the IRA suspected him of being part of a group of police involved in the sectarian killings of Catholics.Parkinson, pp. 137–138. These attacks sparked violence by Loyalists. Belfast suffered three days of sectarian rioting and shooting incidents, during which at least 14 people were killed; including three Catholics taken from their homes and killed by uniformed police. About 150 Catholic families were forced out of their homes at that time. Violence continued throughout the summer of 1921 with August being particularly bad in Belfast: 23 people were killed (12 Protestants and 11 Catholics).

Partition of Ireland

The Government of Ireland Act came into force on 3 May 1921, thus partitioning Ireland under British law.O'Day, Alan (1998). ''Irish Home Rule, 1867–1921''. Manchester University Press, p. 299 Elections for the Northern and Southern parliaments were held on 24 May. Unionists won most of the seats in Northern Ireland, while republicans treated it as an election for the Dáil. TheNorthern Ireland parliament

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore or ...

first met on 7 June and formed a devolved government, headed by Unionist Party leader James Craig James or Jim Craig may refer to:

Entertainment

* James Humbert Craig (1877–1944), Irish painter

* James Craig (actor) (1912–1985), American actor

* James Craig (''General Hospital''), fictional character on television, a.k.a. Jerry Jacks

* J ...

. Irish nationalist and republican members refused to attend. The following day, the IRA ambushed a USC patrol at Carrogs, near Newry

Newry (; ) is a City status in Ireland, city in Northern Ireland, standing on the Newry River, Clanrye river in counties County Down, Down and County Armagh, Armagh. It is near Republic of Ireland–United Kingdom border, the border with the ...

. In reprisal, the Special Constables went to the nearest Catholic home and fatally shot two civilian men. The IRA then fired on the USC men from a nearby hill, killing one.

Opening of the Northern Parliament

King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

George was born during the reign of his pa ...

addressed the ceremonial opening of the Northern Parliament on 22 June 1921. He called for "all Irishmen to pause, to stretch out the hand of forbearance and conciliation". The next day, a train carrying the king's military escort, the 10th Royal Hussars

The 10th Royal Hussars (Prince of Wales's Own) was a Cavalry regiments of the British Army, cavalry regiment of the British Army raised in 1715. It saw service for three centuries including the World War I, First World War and World War II, Sec ...

, was derailed by an IRA bomb at Adavoyle, County Armagh. Five soldiers and a train guard were killed in the derailment, as were fifty horses. Patrick McAteer, a local farm worker, was fatally wounded on the same day roughly half a mile from the ambush site by soldiers when he failed to halt when challenged. On 6 July, disguised Special Constables raided homes at Altnaveigh, County Armagh, and summarily killed four Catholic civilian men.

Belfast's Bloody Sunday

On 9 July 1921, a ceasefire (or truce) was agreed between representatives of the Irish Republic and the British government, to begin at noon on 11 July. Many Loyalists condemned the truce as a 'sell-out' to Republicans.Bell, J Bowyer. ''The Secret Army: The IRA''. Transaction Publishers, 1997. pp. 29–30; While violence may have ceased in the south of Ireland, the birth of Northern Ireland in 1921 saw another wave of intense sectarian violence in Belfast. This period of time saw the highest number of casualties since the Shipyard Clearances of the previous summer. Hours before the ceasefire was to begin, police launched a raid against Republicans in west Belfast. The IRA ambushed them on Raglan Street, killing an officer (Constable Thomas Conlon) and wounding others. This sparked a day of violence known as Belfast's Bloody Sunday. Protestant loyalists attacked Catholic neighbourhoods in west Belfast, burning over 150 Catholic homes and businesses. This led to sectarian clashes and gun battles between police and Catholic nationalists. While the IRA was involved in some of the fighting, another Irish nationalist group, the Hibernians were involved on the Catholic side. The USC were alleged to have driven through Catholic enclaves firing indiscriminately.Parkinson, ''Belfast's Unholy War'', pp. 151–155 Twenty eight people were killed or fatally wounded (including twelve Catholics and six Protestants) from the beginning of the truce (which began at noon on 11 July 1921) and into the following week. Almost 200 houses were badly damaged or destroyed, most of them being Catholic homes. With the ceasefire a strict curfew was enforced in Belfast and the Commandant of the IRA's 2nd Northern Division,Eoin O'Duffy

Eoin O'Duffy (born Owen Duffy; 28 January 1890 – 30 November 1944) was an Irish revolutionary, soldier, police commissioner, politician and fascist. O'Duffy was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a promin ...

, was sent to Belfast to liaise with the authorities and to try to maintain the truce. McGarry, Fearghal (2005). ''Eoin O'Duffy, a Self-Made Hero''. Oxford University Press, pp. 78–79. With the tacit consent of the RIC, in order to restore order, O'Duffy organized IRA patrols in Catholic neighborhoods and announced that IRA offensive actions would end. Both Protestants and Catholics saw the truce as a victory for Republicans. Loyalists "were particularly appalled by the sight of policemen and soldiers meeting IRA officers on a semi-official basis".

Ulster

During this time period violence occurred in all nine counties of Ulster. Outside of the major cities/towns many attacks occurred in smaller/rural communities and were mostly limited to attacks on RIC barracks, ambushes, sniping and raids for weapons. Some large-scale attacks did occur, often involving up to 200 IRA members. On 9 May 1920 approximately 200 IRA volunteers (under the command of Armagh native)Frank Aiken

Francis Thomas Aiken (13 February 1898 – 18 May 1983) was an Irish revolutionary and politician. He was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army, chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army (1922–1969), Anti-Treaty IRA at the end of the I ...

attacked the RIC barracks in Newtownhamilton, County Armagh. After a two-hour firefight, the IRA breached the barracks wall with explosives and stormed the building.

Another large scale battle took place on 1 June 1920 when at least 200 IRA volunteers led by Roger McCorley

Roger McCorley (6 September 1901 – 13 November 1993) was an Irish republican activist.

Early life

Roger Edmund McCorley was born into a Roman Catholic family at 67 Hillman Street in Belfast on 6 September 1901, one of three children born to ...

attacked the RIC barracks in Crossgar, County Down. They opened fire on the building, wounding two officers, and attempted to breach the walls with explosives before withdrawing. In early 1921, western Donegal had seasoned Volunteers under the command of Peadar O'Donnell

Peadar O'Donnell (; 22 February 1893 – 13 May 1986) was one of the foremost radicals of 20th-century Ireland. O'Donnell became prominent as an Irish republican, socialist politician and writer.

Early life

Peadar O'Donnell was born into an I ...

. During this time the west Donegal Flying Column

A flying column is a small, independent, military land unit capable of rapid mobility and usually composed of all arms. It is often an ''ad hoc'' unit, formed during the course of operations.

The term is usually, though not necessarily, appl ...

was responsible for numerous successful attacks on RIC barracks and troop train ambushes. On 12 January 1921, the column attacked a train carrying troops with multiple military deaths reported.

Attacks and reprisals were common. On 25 October 1920 (after a successful raid for arms/ammunition took place at the RIC barracks in Tempo, County Fermanagh), a RIC officer was seriously wounded. Several hours later members of the UVF fired into a group of civilians in Tempo, killing one and wounding another. On 22 February 1921 in the small town of Mountcharles

Mountcharles () is a village and townland (of 650 acres) in the south of County Donegal in Ulster, the northern province in Ireland. It lies 6 km from Donegal Town on the Killybegs road ( N56). It is situated in the civil parish of Inver ...

, County Donegal, the IRA attacked a mixed patrol of military and police, one RIC officer was killed and a soldier was wounded during a 30 minute exchange of gunfire. Later that day, police and Black and Tans in Donegal town fired shots into buildings, destroyed shops and licensed premises. After midnight a mixed force of RIC, Black and Tans, USC and military returned to Mountcharles destroying businesses and setting fire to homes. That night one woman was shot and killed in Mountcharles. On 22 March 1921, in retaliation for the burning of Catholic owned homes in Rosslea, County Fermanagh (21 February 1921) two members of the USC were shot dead. The IRA also conducted widespread attacks on Protestant owned homes in Rosslea, burning at least two to the ground and damaging many others. The following month, the IRA attacked the homes of up to sixteen Special Constables in the Rosslea district, killing three and wounding several others.

In Ulster during the spring of 1921, numerically superior British/Unionist forces faced a poorly armed IRA. The situation in County Tyrone at that time highlights the problems faced by the IRA when confronted with large numbers of military, police and Special Constabulary

The Special Constabulary is the part-time volunteer section of statutory police forces in the United Kingdom and some Crown dependencies. Its officers are known as special constables.

Every United Kingdom territorial police force has a speci ...

: "By the early spring of 1921 there were 3,515 A and 11,000 B Specials in the six county area. At the time of the truce there were about 14 reasonably active IRA companies in Tyrone, each with around 50 men, but only half a dozen in each company were armed. Therefore, just over 100 poorly armed Volunteers faced a combined force of almost 3,000 heavily armed, paramilitary police comprising RIC, A and B Specials". The British Army was also represented in Tyrone with a 650 man Rifle Brigade based in the border town of Strabane

Strabane (; ) is a town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland.

Strabane had a population of 13,507 at the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 census. This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under th Open Government Li ...

, County Tyrone. Some areas of Ulster saw little violence – only three IRA volunteers were killed in County Cavan

County Cavan ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is part of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Cavan and is based on the hi ...

during the war. For a more complete listing of the troubles in Ulster during this time period see Timeline of the Irish War of Independence

A timeline is a list of events displayed in chronological order. It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labelled with dates paralleling it, and usually contemporaneous events.

Timelines can use any suitable scale representing ...

.

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The post-ceasefire talks led to theAnglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

, signed on 6 December 1921 by representatives of the British government and the Irish Republic. Under the Treaty, 'Southern Ireland' would leave the UK and become a self-governing dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

: the Irish Free State