Tahiti, French Polynesia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tahiti (; Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward group of the

Tahiti is the highest and largest island in French Polynesia lying close to Moorea island. It is located south of Hawaii, from

Tahiti is the highest and largest island in French Polynesia lying close to Moorea island. It is located south of Hawaii, from

Atlas démographique 2007. ispf.pf ''Tahiti Iti'' has remained isolated, as its southeastern half (''Te Pari'') is accessible only to those travelling by boat or on foot. The rest of the island is encircled by a main road which cuts between the mountains and the sea. Tahiti's landscape features lush

. Weatherbase.com. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the island was divided into territories, each dominated by a single clan. The most important clans were the closely related Teva i Uta (Teva of the Interior) and the Teva i Tai (Teva of the Sea)Bernard Gille, Antoine Leca (2009) ''Histoire des institutions de l'Océanie française: Polynésie, Nouvelle-Calédonie, Wallis et Futuna'', L'Harmattan, whose combined territory extended from the peninsula in the south of Tahiti Nui. Salvat, p. 187

Clan leadership consisted of a chief (''arii rahi''), nobles (''arii''), and under-chiefs (''Īatoai''). The arii were also the religious leaders, revered for the

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the island was divided into territories, each dominated by a single clan. The most important clans were the closely related Teva i Uta (Teva of the Interior) and the Teva i Tai (Teva of the Sea)Bernard Gille, Antoine Leca (2009) ''Histoire des institutions de l'Océanie française: Polynésie, Nouvelle-Calédonie, Wallis et Futuna'', L'Harmattan, whose combined territory extended from the peninsula in the south of Tahiti Nui. Salvat, p. 187

Clan leadership consisted of a chief (''arii rahi''), nobles (''arii''), and under-chiefs (''Īatoai''). The arii were also the religious leaders, revered for the

In 1819, Pōmare II, encouraged by the missionaries, introduced the first Tahitian legal code, known under the name of the Pōmare Legal Code, which consists of nineteen laws. The missionaries and Pōmare II thus imposed a ban on nudity (obliging them to wear clothes covering their whole body), banned dances and chants (described as immodest), tattoos, and costumes made of flowers.

In the 1820s, the entire population of Tahiti converted to Protestantism. Duperrey, who berthed in Tahiti in May 1823, attests to the change in Tahitian society in a letter dated 15 May 1823: "The missionaries of the Royal Society of London have totally changed the morals and customs of the inhabitants. Idolatry no longer exists among them, and they generally profess the Christian religion. The women no longer come aboard the vessel, and even when we meet them on land they are extremely reserved. (...) The bloody wars that these people used to carry out and human sacrifices have no longer taken place since 1816."

When, on 7 December 1821, Pōmare II died, his son Pōmare III was only eighteen months old. His uncle and the religious people therefore supported the regency, until 2 May 1824, the date on which the missionaries conducted his coronation, a ceremony unprecedented in Tahiti. Taking advantage of the weakness of the Pōmare, local chiefs won back some of their power and took the hereditary title of ''Tavana'' (from the English word "governor"). The missionaries also took advantage of the situation to change the way in which powers were arranged, and to make the Tahitian monarchy closer to the English model of a constitutional monarchy. They therefore created the Tahitian Legislative Assembly, which first sat on 23 February 1824.

In 1827, the young

In 1819, Pōmare II, encouraged by the missionaries, introduced the first Tahitian legal code, known under the name of the Pōmare Legal Code, which consists of nineteen laws. The missionaries and Pōmare II thus imposed a ban on nudity (obliging them to wear clothes covering their whole body), banned dances and chants (described as immodest), tattoos, and costumes made of flowers.

In the 1820s, the entire population of Tahiti converted to Protestantism. Duperrey, who berthed in Tahiti in May 1823, attests to the change in Tahitian society in a letter dated 15 May 1823: "The missionaries of the Royal Society of London have totally changed the morals and customs of the inhabitants. Idolatry no longer exists among them, and they generally profess the Christian religion. The women no longer come aboard the vessel, and even when we meet them on land they are extremely reserved. (...) The bloody wars that these people used to carry out and human sacrifices have no longer taken place since 1816."

When, on 7 December 1821, Pōmare II died, his son Pōmare III was only eighteen months old. His uncle and the religious people therefore supported the regency, until 2 May 1824, the date on which the missionaries conducted his coronation, a ceremony unprecedented in Tahiti. Taking advantage of the weakness of the Pōmare, local chiefs won back some of their power and took the hereditary title of ''Tavana'' (from the English word "governor"). The missionaries also took advantage of the situation to change the way in which powers were arranged, and to make the Tahitian monarchy closer to the English model of a constitutional monarchy. They therefore created the Tahitian Legislative Assembly, which first sat on 23 February 1824.

In 1827, the young  In November 1835

In November 1835  In Sept. 1839, the island was visited by the

In Sept. 1839, the island was visited by the

Tahiti is part of French Polynesia. French Polynesia is a semi-autonomous territory of France with its own assembly, president, budget and laws. France's influence is limited to subsidies, education, and security.

Tahitians are French citizens with complete civil and political rights. French is the official language, but Tahitian and French are both in use. However there was a time during the 1960s and 1970s when children were forbidden to speak Tahitian in schools. Tahitian is now taught in schools; it is sometimes even a requirement for employment.

During a press conference on 26 June 2006 during the second France-Oceania Summit, French President

Tahiti is part of French Polynesia. French Polynesia is a semi-autonomous territory of France with its own assembly, president, budget and laws. France's influence is limited to subsidies, education, and security.

Tahitians are French citizens with complete civil and political rights. French is the official language, but Tahitian and French are both in use. However there was a time during the 1960s and 1970s when children were forbidden to speak Tahitian in schools. Tahitian is now taught in schools; it is sometimes even a requirement for employment.

During a press conference on 26 June 2006 during the second France-Oceania Summit, French President

The places of birth of the 189,517 residents of the island of Tahiti at the 2017 census were the following:

*75.4% were born in Tahiti (up from 71.5% at the 2007 census)

*9.3% in

The places of birth of the 189,517 residents of the island of Tahiti at the 2017 census were the following:

*75.4% were born in Tahiti (up from 71.5% at the 2007 census)

*9.3% in

The main trading partners are Metropolitan France for about 40% of imports and about 25% of exports. The other main trading partners are China, the US, South Korea, and New Zealand.

The main trading partners are Metropolitan France for about 40% of imports and about 25% of exports. The other main trading partners are China, the US, South Korea, and New Zealand.

As is mentioned in records of Captain Cook's visits, breadfruit is a staple crop. One main way of preparing it is documented in

As is mentioned in records of Captain Cook's visits, breadfruit is a staple crop. One main way of preparing it is documented in

Faaā International Airport is located from Papeete in the commune of Faaā and is the only

Faaā International Airport is located from Papeete in the commune of Faaā and is the only

Tahitian Heritage

in French with Google Translation available {{Communes of Tahiti Members of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization Islands of the Society Islands

Society Islands

The Society Islands ( , officially ; ) are an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean that includes the major islands of Tahiti, Mo'orea, Moorea, Raiatea, Bora Bora and Huahine. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country ...

in French Polynesia

French Polynesia ( ; ; ) is an overseas collectivity of France and its sole #Governance, overseas country. It comprises 121 geographically dispersed islands and atolls stretching over more than in the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. The t ...

, an overseas collectivity

The French overseas collectivities ( abbreviated as COM) are first-order administrative divisions of France, like the French regions, but have a semi-autonomous status. The COMs include some former French overseas colonies and other French ...

of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

and the nearest major landmass is the North Island

The North Island ( , 'the fish of Māui', historically New Ulster) is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but less populous South Island by Cook Strait. With an area of , it is the List ...

of New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. The island was formed from volcanic

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often fo ...

activity in two overlapping parts, ''Tahiti Nui'' (bigger, northwestern part) and ''Tahiti Iti'' (smaller, southeastern part); it is high and mountainous with surrounding coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

s. Its population was 189,517 in 2017, making it by far the most populous island in French Polynesia and accounting for 68.7% of its total population; the 2022 Census recorded a population of 191,779.

Tahiti is the economic, cultural, and political centre of French Polynesia. The capital of French Polynesia, Papeete

Papeete (Tahitian language, Tahitian: ''Papeʻetē'', pronounced ; old name: ''Vaiʻetē''Personal communication with Michael Koch in ) is the capital city of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of the France, French Republic in the Pacific ...

, is located on the northwest coast of Tahiti. The only international airport in the region, Faaā International Airport, is on Tahiti near Papeete. Tahiti was originally settled by Polynesians

Polynesians are an ethnolinguistic group comprising closely related ethnic groups native to Polynesia, which encompasses the islands within the Polynesian Triangle in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sout ...

between . They represent about 70% of the island's population, with the rest made up of Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common ancestry, language, faith, historical continuity, etc. There are ...

, Chinese

Chinese may refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people identified with China, through nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**Han Chinese, East Asian ethnic group native to China.

**'' Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic ...

and those of mixed heritage. The island was part of the Kingdom of Tahiti

The Kingdom of Tahiti or the Tahitian Kingdom was a Polynesian monarchy founded by paramount chief Pōmare I, who, with the aid of British missionaries and traders, and European weaponry, unified the islands of Tahiti, Moʻorea, Teti‘aroa, ...

until its annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

by France in 1880, when it was proclaimed a colony of France, and the inhabitants became French citizens. French is the sole official language, although the Tahitian language

Tahitian (autonym: , , part of , , languages of French Polynesia) correspond to "languages of natives from French Polynesia", and may in principle designate any of the seven indigenous languages spoken in French Polynesia. The Tahitian language s ...

(''Reo Tahiti'') is also widely spoken.

Tahiti was called ''Otaheite'' in earlier European documents: this is a rendering of the Tahitian phrase , which is typically pronounced .

Geography

Tahiti is the highest and largest island in French Polynesia lying close to Moorea island. It is located south of Hawaii, from

Tahiti is the highest and largest island in French Polynesia lying close to Moorea island. It is located south of Hawaii, from Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, from Australia.

The island is across at its widest point and covers an area of . The highest peak is Mont Orohena (Moua Orohena) (). Mount Roonui, or Mount Ronui (Moua Rōnui), in the southeast rises to . The island consists of two roughly round portions centered on volcanic mountains and connected by a short isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

of Taravao.

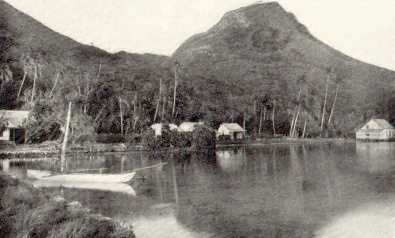

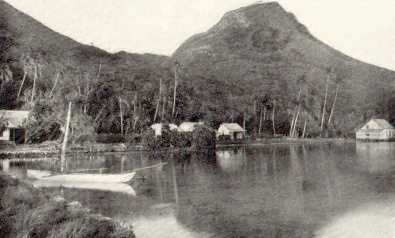

The northwestern portion is known as ''Tahiti Nui'' ("big Tahiti"), while the much smaller southeastern portion is known as ''Tahiti Iti'' ("small Tahiti") or ''Taiarapū''. ''Tahiti Nui'' is heavily populated along the coast, especially around the capital, Papeete.

The interior of ''Tahiti Nui'' is almost entirely uninhabited.Population Densité de populationAtlas démographique 2007. ispf.pf ''Tahiti Iti'' has remained isolated, as its southeastern half (''Te Pari'') is accessible only to those travelling by boat or on foot. The rest of the island is encircled by a main road which cuts between the mountains and the sea. Tahiti's landscape features lush

rainforest

Rainforests are forests characterized by a closed and continuous tree Canopy (biology), canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforests can be generally classified as tropi ...

s and many rivers and waterfalls, including the Papenoo on the north side and the Fautaua Falls near Papeete

Papeete (Tahitian language, Tahitian: ''Papeʻetē'', pronounced ; old name: ''Vaiʻetē''Personal communication with Michael Koch in ) is the capital city of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of the France, French Republic in the Pacific ...

.

Geology

Both ''Tahiti Nui'' and ''Tahiti Iti'' are extinct and heavily erodedshield volcanoes

A shield volcano is a type of volcano named for its low profile, resembling a shield lying on the ground. It is formed by the eruption of highly fluid (low viscosity) lava, which travels farther and forms thinner flows than the more viscous lava ...

which formed from volcanic activity associated with the Society hotspot

The Society hotspot is a volcanic hotspot in the south Pacific Ocean which is responsible for the formation of the Society Islands, an archipelago of fourteen volcanic islands and atolls spanning around of the ocean which formed between 4.5 and ...

.

Climate

November to April is the wet season, the wettest month of which is January with of rain in Papeete. August is the driest with . The average temperature ranges between , with little seasonal variation. The lowest and highest temperatures recorded in Papeete are , respectively.Papeete, French Polynesia. Weatherbase.com. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

History

Early settling of Tahiti

The first Tahitians arrived from Western Polynesia into theSociety Islands

The Society Islands ( , officially ; ) are an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean that includes the major islands of Tahiti, Mo'orea, Moorea, Raiatea, Bora Bora and Huahine. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country ...

sometime after ; some studies have proposed slightly later dates, . Linguistic, biological and archaeological evidence supports a long migration from Southeast Asia via the Fijian, Samoan and Tongan Archipelagos using outrigger canoe

Outrigger boats are various watercraft featuring one or more lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are fastened to one or both sides of the main hull (watercraft), hull. They can range from small dugout (boat), dugout canoes to large ...

s that were up to twenty or thirty metres long and could transport families as well as domestic animals.

Civilization before the arrival of the Europeans

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the island was divided into territories, each dominated by a single clan. The most important clans were the closely related Teva i Uta (Teva of the Interior) and the Teva i Tai (Teva of the Sea)Bernard Gille, Antoine Leca (2009) ''Histoire des institutions de l'Océanie française: Polynésie, Nouvelle-Calédonie, Wallis et Futuna'', L'Harmattan, whose combined territory extended from the peninsula in the south of Tahiti Nui. Salvat, p. 187

Clan leadership consisted of a chief (''arii rahi''), nobles (''arii''), and under-chiefs (''Īatoai''). The arii were also the religious leaders, revered for the

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the island was divided into territories, each dominated by a single clan. The most important clans were the closely related Teva i Uta (Teva of the Interior) and the Teva i Tai (Teva of the Sea)Bernard Gille, Antoine Leca (2009) ''Histoire des institutions de l'Océanie française: Polynésie, Nouvelle-Calédonie, Wallis et Futuna'', L'Harmattan, whose combined territory extended from the peninsula in the south of Tahiti Nui. Salvat, p. 187

Clan leadership consisted of a chief (''arii rahi''), nobles (''arii''), and under-chiefs (''Īatoai''). The arii were also the religious leaders, revered for the mana

Mana may refer to:

Religion and mythology

* Mana (Oceanian cultures), the spiritual life force energy or healing power that permeates the universe in Melanesian and Polynesian mythology

* Mana (food), archaic name for manna, an edible substance m ...

(spiritual power) they inherited as descendants of the gods. As symbols of their power, they wore belts of red feathers. Nonetheless, to exercise their political power, councils or general assemblies composed of the arii and the Īatoai had to be called, especially in case of war.

The chief's spiritual power was also limited; each clan's practice was organized around their ''marae'' (stone temple) and its priests.

First European visits

The first European to arrive at Tahiti may have been Spanish explorer Juan Fernández in his expedition of 1576–1577. Alternatively, Portuguese navigatorPedro Fernandes de Queirós

Pedro Fernandes de Queirós () (1563–1614) was a Portuguese navigator in the service of Spain. He is best known for leading several Spanish voyages of discovery in the Pacific Ocean, in particular the 1595–1596 voyage of Álvaro de Mendaña y ...

, serving the Spanish Crown

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a Hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish ...

in an expedition to ''Terra Australis

(Latin for ) was a hypothetical continent first posited in antiquity and which appeared on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries. Its existence was not based on any survey or direct observation, but rather on the idea that continental l ...

'', was perhaps the first European to see Tahiti. He sighted an inhabited island on 10 February 1606. However, it has been suggested that he actually saw the island of Rekareka

Rekareka, Tehuata or Tu-henua, is an atoll of the Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia. It is located in the Centre East of the group, 83 km southeast from Raroia,

and lies 70 km NW of Tauere, its nearest neighbor. The shoal water ...

to the southeast of Tahiti. Hence, although the Spanish and Portuguese made contact with nearby islands, they may not have arrived at Tahiti.

The next stage of European visits to the region came during the period of intense Anglo-French rivalry that filled the twelve years between the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

and the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. The first of these visits, and perhaps the first European visit to Tahiti, was under the command of Captain Samuel Wallis

Post-captain, Captain Samuel Wallis (23 April 1728 – 21 January 1795) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who made the first recorded visit by a European navigator to Tahiti.

Biography

Wallis was born at Fenteroon Farm, near Camelfo ...

. While circumnavigating the globe in , they sighted the island on 18 June 1767 and then harbored in Matavai Bay Matavai Bay is a bay on the north coast of Tahiti, the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia. It is in the commune of Mahina, approximately 8 km east of the capital Pape'ete.

Early European voyages

The bay was visited by E ...

between the chiefdom Pare

In aviation, PARE is a mnemonic for a generic spin recovery technique applicable to many types of fixed-wing aircraft, abbreviating the terms ''power'', ''ailerons'', ''rudder'', and ''elevator''.

Overview

PARE stands for:

*Power: idle

*Ailerons ...

- Arue (governed by Tu (Tu-nui-e-aa-i-te-Atua) and his regent Tutaha) and the chiefdom Haapape, governed by Amo and his wife "Oberea" (Purea

Purea, Tevahine-'ai-roro-atua-i-Ahurai, also called ''Oborea'' (floruit 1769), was a queen from the Landward Teva tribe and a self-proclaimed ruler of all Tahiti. Queen Purea is known from the first famous European expeditions to Tahiti. She rule ...

). The initially friendly encounter turned tense as islanders grew suspicious and sought control of the Dolphin, leading to a week of skirmishes that culminated in violence, Salvat, pp. 44–45 but to avert all-out war after a British show of force, Oberea laid down peace offerings leading to cordial relations.

On 2 April 1768, the expedition of Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, aboard and on the first French circumnavigation, sighted Tahiti. On 5 April, they anchored off Hitiaa O Te Ra and were welcomed by its chief Reti. Bougainville was also visited by Tutaha. Bougainville stayed about ten days.

By 12 April 1769 Captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

had arrived in Tahiti's Matavai Bay on a scientific mission with astronomy, botany, and artistic details. On 14 April Cook met Tutaha and Tepau and the next day he picked the site for a fortified camp at Point Venus for Charles Green's observatory. Botanist Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

and artist Sydney Parkinson

Sydney Parkinson ( 1745 – 26 January 1771) was a Scottish botanical illustrator and natural history artist. He was the first European artist to visit Australia, New Zealand and Tahiti. Parkinson was the first Quaker to visit New Zealand.

...

, along with Cook, gathered valuable information on fauna and flora as well as on native society, language and customs, including the proper name of the island. Cook also met many island chiefs. Cook and ''Endeavour'' left Tahiti on 13 July 1769. Cook estimated the population to be 200,000 including all the nearby islands in the chain. This estimate was reduced to 35,000 by Cook's contemporary, anthropologist and Tahiti expert Douglas L. Oliver.

The Viceroy of Peru, Manuel de Amat y Juniet

Manuel de Amat y Junyent, OSJ, OM () (March 1707 – February 14, 1782) was a Spanish military officer and colonial administrator. He was the Royal Governor of the Captaincy General of Chile from December 28, 1755, to September 9, 1761, and V ...

, under order of the Spanish Crown, organized an expedition to colonize the island in 1772. He would ultimately send three expeditions aboard the ship ''Aguila'', the first two under the command of navigator Domingo de Bonechea

Domingo Bernardo de Bonechea Andonaegui (21 September 1713 – 26 January 1775) was a Spanish Navy officer and explorer. He is known for having tried to incorporate Tahiti into the Spanish Empire. De Bonechea's exploratory voyages were commission ...

. Four Tahitians, Pautu, Tipitipia, Heiao, and Tetuanui, accompanied Bonechea back to Peru in early 1773 after the first ''Aguila'' expedition.

Cook returned to Tahiti between 15 August and 1 September 1773. Greeted by the chiefs, Cook anchored in Vaitepiha Bay before returning to Point Venus. Cook left Tahiti on 14 May 1774.

Pautu and Tetuanui returned to Tahiti with Bonechea aboard ''Aguila'' on 14 November 1774; Tipitipia and Heiao had died. Bonechea died on 26 January 1775 in Tahiti and was buried near the mission he had established at Tautira Bay. Lt Tomas Gayangos took over command and set sail for Peru on 27 January, leaving the Fathers Geronimo Clota and Narciso Gonzalez and the sailors Maximo Rodriguez and Francisco Perez in charge of the mission. On the third ''Aguila'' expedition, under Don Cayetano de Langara, the mission on Tahiti was abandoned on 12 November 1775, when the Fathers successfully begged to be taken back to Lima.

During his final visit in 1777 Cook first moored in Vaitepiha Bay. From there he reunited with many Tahitian clans and established British presence on the remains of the Spanish mission. On 29 September 1777 Cook sailed for Papetoai Bay on Moorea.

British influence and the rise of the Pōmare

Mutineers of the ''Bounty''

On 26 October 1788, , under the command of CaptainWilliam Bligh

William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was a Vice-admiral (Royal Navy), Royal Navy vice-admiral and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New South Wales from 1806 to 1808. He is best known for his role in the Muti ...

, landed in Tahiti with the mission of carrying Tahitian breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to have been selectively bred in Polynesia from the breadnut ('' Artocarpus camansi''). Breadfruit was spread into ...

trees ( Tahitian: ''uru'') to the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

. Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

, the botanist from James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

's first expedition, had concluded that this plant would be ideal to feed the African slaves working in the Caribbean plantations at very little cost. The crew remained in Tahiti for about five months, the time needed to transplant the seedlings of the trees. Three weeks after leaving Tahiti, on 28 April 1789, the crew mutinied on the initiative of Fletcher Christian

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 – 20 September 1793) was an English sailor who led the mutiny on the ''Bounty'' in 1789, during which he seized command of the Royal Navy vessel from Lieutenant William Bligh.

In 1787, Christian was ap ...

. The mutineers seized the ship and set the captain and most of those members of the crew who remained loyal to him adrift in a ship's boat. A group of mutineers then went back to settle in Tahiti, after which the Bounty, under Christian, sailed to Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, in the southern Pacific Ocean, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff ...

.

Although various explorers had refused to get involved in tribal conflicts, the mutineers from the ''Bounty'' offered their services as mercenaries and furnished arms to the family which became the Pōmare Dynasty Pōmare or Pomare may refer to:

Tahiti

* Pōmare dynasty, the dynasty of the Tahitian monarchs

* Pōmare I (c. 1742–1803), first king of the Kingdom of Tahiti

* Pōmare II (c. 1774–1821), second king of Tahiti

* Pōmare III (1820–1827), third ...

. The chief Tū knew how to use their presence in the harbours favoured by sailors to his advantage. As a result of his alliance with the mutineers, he succeeded in considerably increasing his supremacy over the island of Tahiti.

In about 1790, the ambitious chief Tū took the title of king and gave himself the name ''Pōmare''. Captain Bligh explains that this name was a homage to his eldest daughter Teriinavahoroa, who had died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, "an illness that made her cough (''mare'') a lot, especially at night (''pō'')". Thus he became Pōmare I

Pōmare I (c. 1753 – September 3, 1803) (fully in old orthography: Tu-nui-ea-i-te-atua-i-Tarahoi Vaira'atoa Taina Pōmare I; also known as Tu or Tinah or Outu, or more formally as Tu-nui-e-a'a-i-te-atua) was the unifier and first king of T ...

, founding the Pōmare Dynasty and his lineage would be the first to unify Tahiti from 1788 to 1791. He and his descendants founded and expanded Tahitian influence to all of the lands that now constitute modern French Polynesia.

In 1791, under Captain Edward Edwards called at Tahiti and took custody of fourteen of the mutineers. Four were drowned in the sinking of ''Pandora'' on her homeward voyage, three were hanged, four were acquitted, and three were pardoned.

Landings of the whalers

In the 1790s,whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

s began landing at Tahiti during their hunting expeditions in the southern hemisphere. The arrival of these whalers, who were subsequently joined by merchants coming from the penal colonies in Australia, marked the first major overturning of traditional Tahitian society. The crews introduced alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

, arms and infectious diseases to the island. These commercial interactions with westerners had catastrophic consequences for the Tahitian population, which shrank rapidly, ravaged by diseases and other cultural factors. During the first decade of the 19th century, the Tahitian population dropped from 16,000 to 8,000–9,000; the French census in 1854 counted a population just under 6,000.

Arrival of the missionaries

On 5 March 1797, representatives of theLondon Missionary Society

The London Missionary Society was an interdenominational evangelical missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Edward Williams. It was largely Reformed tradition, Reformed in outlook, with ...

landed at Matavai Bay Matavai Bay is a bay on the north coast of Tahiti, the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia. It is in the commune of Mahina, approximately 8 km east of the capital Pape'ete.

Early European voyages

The bay was visited by E ...

( Mahina) on board ''Duff'', with the intention of converting the pagan native populations to Christianity. The arrival of these missionaries marked a new turning point for the island of Tahiti, having a lasting impact on the local culture.

The first years proved hard work for the missionaries, despite their association with the Pōmare, the importance of whom they were aware of thanks to the reports of earlier sailors. In 1803, upon the death of Pōmare I

Pōmare I (c. 1753 – September 3, 1803) (fully in old orthography: Tu-nui-ea-i-te-atua-i-Tarahoi Vaira'atoa Taina Pōmare I; also known as Tu or Tinah or Outu, or more formally as Tu-nui-e-a'a-i-te-atua) was the unifier and first king of T ...

, his son Vairaatoa succeeded him and took the title of Pōmare II. He allied himself more and more with the missionaries, and from 1803 they taught him reading and the Gospels. Furthermore, the missionaries encouraged his wish to conquer his opponents, so that they would only have to deal with a single political contact, enabling them to develop Christianity in a unified country. The conversion of Pōmare II to Protestantism in 1812 marks moreover the point when Protestantism truly took off on the island.

In about 1810, Pōmare II

Pōmare II (c. 1782 – 7 December 1821) (fully Tu Tunuieaiteatua Pōmare II or in modern orthography Tū Tū-nui-ʻēʻa-i-te-atua Pōmare II; historically misspelled as Tu Tunuiea'aite-a-tua), was the second king of Tahiti between 1782 and 182 ...

married Teremoemoe daughter of the chief of Raiatea, to ally himself with the chiefdoms of the Leeward Islands

The Leeward Islands () are a group of islands situated where the northeastern Caribbean Sea meets the western Atlantic Ocean. Starting with the Virgin Islands east of Puerto Rico, they extend southeast to Guadeloupe and its dependencies. In Engl ...

. On 12 November 1815, thanks to these alliances, Pōmare II won a decisive battle at Fei Pī (Punaauia), notably against Opuhara, the chief of the powerful clan of Teva. This victory allowed Pōmare II to be styled ''Arii Rahi'', or the king of Tahiti. It was the first time that Tahiti had been united under the control of a single family. This marked the end of Tahitian feudalism and the military aristocracy, which were replaced by an absolute monarchy. At the same time, Protestantism quickly spread, thanks to the support of Pōmare II, and replaced the traditional beliefs. In 1816 the London Missionary Society sent John Williams

John Towner Williams (born February 8, 1932)Nylund, Rob (November 15, 2022)Classic Connection review, ''WBOI'' ("For the second time this year, the Fort Wayne Philharmonic honored American composer, conductor, and arranger John Williams, who w ...

as a missionary and teacher, and starting in 1817, the Gospels were translated into Tahitian (''Reo Maohi'') and taught in the religious schools. In 1818, the minister William Pascoe Crook

William Pascoe Crook (1775–1846), a missionary, schoolmaster and pastor. He was born in Dartmouth, Devon, England on 29 April 1775. He was the first missionary to document the Marquesas Islands in an ethnographical account after he was sent b ...

founded the city of Papeete

Papeete (Tahitian language, Tahitian: ''Papeʻetē'', pronounced ; old name: ''Vaiʻetē''Personal communication with Michael Koch in ) is the capital city of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of the France, French Republic in the Pacific ...

, which became the capital of the island.

In 1819, Pōmare II, encouraged by the missionaries, introduced the first Tahitian legal code, known under the name of the Pōmare Legal Code, which consists of nineteen laws. The missionaries and Pōmare II thus imposed a ban on nudity (obliging them to wear clothes covering their whole body), banned dances and chants (described as immodest), tattoos, and costumes made of flowers.

In the 1820s, the entire population of Tahiti converted to Protestantism. Duperrey, who berthed in Tahiti in May 1823, attests to the change in Tahitian society in a letter dated 15 May 1823: "The missionaries of the Royal Society of London have totally changed the morals and customs of the inhabitants. Idolatry no longer exists among them, and they generally profess the Christian religion. The women no longer come aboard the vessel, and even when we meet them on land they are extremely reserved. (...) The bloody wars that these people used to carry out and human sacrifices have no longer taken place since 1816."

When, on 7 December 1821, Pōmare II died, his son Pōmare III was only eighteen months old. His uncle and the religious people therefore supported the regency, until 2 May 1824, the date on which the missionaries conducted his coronation, a ceremony unprecedented in Tahiti. Taking advantage of the weakness of the Pōmare, local chiefs won back some of their power and took the hereditary title of ''Tavana'' (from the English word "governor"). The missionaries also took advantage of the situation to change the way in which powers were arranged, and to make the Tahitian monarchy closer to the English model of a constitutional monarchy. They therefore created the Tahitian Legislative Assembly, which first sat on 23 February 1824.

In 1827, the young

In 1819, Pōmare II, encouraged by the missionaries, introduced the first Tahitian legal code, known under the name of the Pōmare Legal Code, which consists of nineteen laws. The missionaries and Pōmare II thus imposed a ban on nudity (obliging them to wear clothes covering their whole body), banned dances and chants (described as immodest), tattoos, and costumes made of flowers.

In the 1820s, the entire population of Tahiti converted to Protestantism. Duperrey, who berthed in Tahiti in May 1823, attests to the change in Tahitian society in a letter dated 15 May 1823: "The missionaries of the Royal Society of London have totally changed the morals and customs of the inhabitants. Idolatry no longer exists among them, and they generally profess the Christian religion. The women no longer come aboard the vessel, and even when we meet them on land they are extremely reserved. (...) The bloody wars that these people used to carry out and human sacrifices have no longer taken place since 1816."

When, on 7 December 1821, Pōmare II died, his son Pōmare III was only eighteen months old. His uncle and the religious people therefore supported the regency, until 2 May 1824, the date on which the missionaries conducted his coronation, a ceremony unprecedented in Tahiti. Taking advantage of the weakness of the Pōmare, local chiefs won back some of their power and took the hereditary title of ''Tavana'' (from the English word "governor"). The missionaries also took advantage of the situation to change the way in which powers were arranged, and to make the Tahitian monarchy closer to the English model of a constitutional monarchy. They therefore created the Tahitian Legislative Assembly, which first sat on 23 February 1824.

In 1827, the young Pōmare III

Pōmare III (1820–1827), born Teriʻitariʻa, was the king of Tahiti between 1821 and 1827. He was the second son of King Pōmare II and his second wife, Queen Teriʻitoʻoterai Tere-moe-moe. Sources differ on his relation to his sister with ...

suddenly died, and it was his half-sister, Aimata, aged thirteen, who took the title of Pōmare IV

Pōmare IV (28 February 1813 – 17 September 1877), more properly ʻAimata Pōmare IV Vahine-o-Punuateraʻitua (otherwise known as ʻAimata – "eye-eater", after an old custom of the ruler to eat the eye of the defeated foe), was the Queen of ...

. The Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

-born missionary George Pritchard, who was the acting British consul, became her main adviser and tried to interest her in the affairs of the kingdom but the authority of the Queen, who was certainly less charismatic than her father, was challenged by the chiefs, who had won back an important part of their prerogatives since the death of Pōmare II. The power of the Pōmare had become more symbolic than real; time and time again Queen Pōmare, Protestant and anglophile, sought in vain the protection of England.

In November 1835

In November 1835 Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

visited Tahiti aboard HMS ''Beagle'' on her circumnavigation, captained by Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy, politician and scientist who served as the second governor of New Zealand between 1843 and 1845. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of ...

. He was impressed by what he perceived to be the positive influence the missionaries had had on the sobriety and moral character of the population. Darwin praised the scenery, but was not flattering towards Tahiti's Queen Pōmare IV. Captain Fitzroy negotiated payment of compensation for an attack on an English ship by Tahitians, which had taken place in 1833.

In Sept. 1839, the island was visited by the

In Sept. 1839, the island was visited by the United States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

. One of its members, Alfred Thomas Agate

Alfred Thomas Agate (February 14, 1812 – January 5, 1846) was an American painter and miniaturist.

Agate lived in New York from 1831 to 1838, where he studied with his brother, Frederick Styles Agate, a portrait and historical painter. He l ...

, produced a number of sketches of Tahitian life, some of which were later published in the United States.

French protectorate and the end of the Pōmare kingdom

In 1836, the Queen's advisor Pritchard had two French Catholic priests expelled,François Caret

François d'Assise Caret, SS.CC., (born François Toussaint Caret; 4 July 1802 – 26 October 1844) was a French Catholic priest of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, a religious institute of the Roman Catholic Church.

Life ...

and Honoré Laval

Honoré Laval, SS.CC., (born ''Louis-Jacques Laval''; 5/6 February 1808 – 1 November 1880) was a French people, French Catholic priest of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (also known as the Picpus Fathers), a religious ins ...

. As a result, in 1838 France sent Admiral Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars

__NOTOC__

Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars (3 August 1793 – 16 March 1864) was a French naval officer important in France's annexation of French Polynesia.

Early life

He was born at the castle of La Fessardière, near Saumur. His uncle Aristide Aub ...

to obtain reparations. Once his mission had been completed, Admiral Du Petit-Thouars sailed towards the Marquesas

The Marquesas Islands ( ; or ' or ' ; Marquesan: ' ( North Marquesan) and ' ( South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in the southern Pacific ...

Islands, which he annexed in 1842. Also in 1842, a European crisis involving Morocco escalated between France and Great Britain, souring their relations. In August 1842, Admiral Du Petit-Thouars returned and landed in Tahiti. He then made friends with Tahitian chiefs who were hostile to the Pōmare family and favourable to a French protectorate. He had them sign a request for protection in the absence of their Queen, before then approaching her and obliging her to ratify the terms of the treaty of protectorate. The treaty had not even been ratified by France itself when Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout was named royal commissaire alongside Queen Pōmare.

Within the framework of this treaty, France recognised the sovereignty of the Tahitian state. The Queen was responsible for internal affairs, while France would deal with foreign relations and assure the defence of Tahiti, as well as maintain order on the island. Once the treaty had been signed there began a struggle for influence between the English Protestants and the Catholic representatives of France. During the first years of the Protectorate, the Protestants managed to retain a considerable hold over Tahitian society, thanks to their knowledge of the country and its language. George Pritchard had been away at the time. He returned however to work towards indoctrinating the locals against the Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

French.

Tahitian War of independence (1844–47)

In 1843, the Queen's Protestant advisor, Pritchard, persuaded her to display the Tahitian flag in place of the flag of the Protectorate. By way of reprisal, Admiral Dupetit-Thouars announced the annexation of the Kingdom of Pōmare on 6 November 1843 and set up the governorArmand Joseph Bruat

Armand Joseph Bruat ( Colmar, 26 May 1796 – '' Montebello'', off Toulon, 19 November 1855) was a French admiral.

Biography

Bruat joined the French Navy in 1811, at the height of the Napoleonic Wars. His early career included far-ranging se ...

there as the chief of the new colony. He threw Pritchard into prison, and later sent him back to Britain. The annexation caused the Queen to be exiled to the Leeward Islands, and after a period of troubles, a real Franco-Tahitian war began in March 1844. News of Tahiti reached Europe in early 1844. The French statesman

A statesman or stateswoman is a politician or a leader in an organization who has had a long and respected career at the national or international level, or in a given field.

Statesman or statesmen may also refer to:

Newspapers United States

...

François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (; 4 October 1787 – 12 September 1874) was a French historian, orator and Politician, statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics between the July Revolution, Revolution of 1830 and the Revoluti ...

, supported by King Louis-Philippe of France

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his thron ...

, had denounced annexation of the island.

The war ended in December 1846 in favour of the French. The Queen returned from exile in 1847 and agreed to sign a new covenant, considerably reducing her powers, while increasing those of the commissaire. Thus, the French reigned over the Kingdom of Tahiti. In 1863, they put an end to the British influence and replaced the British Protestant Missions with the Société des missions évangéliques de Paris (Society of Evangelical Missions of Paris).

Later 19th century

During the same period about a thousand Chinese, mainlyCantonese

Cantonese is the traditional prestige variety of Yue Chinese, a Sinitic language belonging to the Sino-Tibetan language family. It originated in the city of Guangzhou (formerly known as Canton) and its surrounding Pearl River Delta. While th ...

, were recruited at the request of a plantation owner in Tahiti, William Stewart, to work on the great cotton plantation at Atimaono. When the enterprise resulted in bankruptcy in 1873, some Chinese workers returned to their country, but a large number stayed in Tahiti and mixed with the population.

In 1866 the district councils were formed, elected, which were given the powers of the traditional hereditary chiefs. In the context of the republican assimilation, these councils tried their best to protect the traditional way of life of the local people, which was threatened by European influence.

In 1877, Queen Pōmare died after ruling for fifty years. Her son, Pōmare V, then succeeded her on the throne. The new king seemed little concerned with the affairs of the kingdom, and when in 1880 the governor Henri Isidore Chessé, supported by the Tahitian chiefs, pushed him to abdicate in favour of France, he accepted. On 29 June 1880, he ceded Tahiti to France along with the islands that were its dependencies. He was given the titular position of Officer of the Orders of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

and Agricultural Merit of France. Having become a colony, Tahiti thus lost all sovereignty. Tahiti was nevertheless a special colony, since all the subjects of the Kingdom of Pōmare would be given French citizenship. On 14 July 1881, among cries of "Vive la République!" the crowds celebrated the fact that Polynesia now belonged to France; this was the first celebration of the Tiurai (national and popular festival). In 1890, Papeete became a commune of the Republic of France.

The French painter Paul Gauguin

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (; ; 7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903) was a French painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramist, and writer, whose work has been primarily associated with the Post-Impressionist and Symbolist movements. He was also an influ ...

lived on Tahiti in the 1890s and painted many Tahitian subjects. Papeari

Pape'ari is a village on the south coast of Tahiti. It is located in Tahiti-nui district, around 32 miles from Papeete

Papeete (Tahitian language, Tahitian: ''Papeʻetē'', pronounced ; old name: ''Vaiʻetē''Personal communication with Michael K ...

has a small Gauguin museum.

In 1891 Matthew Turner, an American shipbuilder from San Francisco who had been seeking a fast passage between the city and Tahiti, built , a two-masted schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

that made the trip in seventeen days.

Twentieth century to present

In 1903, the Établissements Français d'Océanie (French Establishments in Oceania) were created, which collected together Tahiti, the otherSociety Islands

The Society Islands ( , officially ; ) are an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean that includes the major islands of Tahiti, Mo'orea, Moorea, Raiatea, Bora Bora and Huahine. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country ...

, the Austral Islands

The Austral Islands ( officially ''Archipel des Australes;'' ) are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of France, overseas country of the France, French Republic in the Oceania, South Pacific. Geographicall ...

, the Marquesas Islands and the Tuamotu Archipelago

The Tuamotu Archipelago or the Tuamotu Islands (, officially ) are a French Polynesian chain of just under 80 islands and atolls in the southern Pacific Ocean. They constitute the largest chain of atolls in the world, extending (from northwest to ...

.

During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Papeete region of the island was attacked by two German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is used for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the navy branch of the armed forces of a nation, though they have also been operated by individuals, cooperatives and corporations. As well as b ...

s. A French gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

as well as a captured German freighter were sunk in the harbour and the two German armoured cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

s bombarded the colony.

Between 1966 and 1996 the French Government conducted 193 nuclear bomb tests above and below the atolls of Moruroa

Moruroa (Mururoa, Mururura), also historically known as Aopuni, is an atoll which forms part of the Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is located about southeast of Tahiti. Administratively Moruroa Atoll i ...

and Fangataufa

Fangataufa (or Fangatafoa) is an uninhabited coral atoll in the eastern part of the Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia. The atoll has been fully-owned by the French state since 1964. From 1966 to 1996 it was used as a nuclear test site by t ...

. The last test was conducted on 27 January 1996.

In 1946, Tahiti and the whole of French Polynesia became an overseas territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

(''Territoire d'outre-mer''). Tahitians were granted French citizenship

French nationality law is historically based on the principles of ''jus soli'' (Latin for "right of soil") and ''jus sanguinis'', (Latin for "right of blood") according to Ernest Renan's definition, in opposition to the German definition of nat ...

, a right that had been campaigned for by nationalist leader Pouvanaa a Oopa

Pouvana'a a O'opa (May 10, 1895 – January 10, 1977) was a Tahitian politician and advocate for French Polynesian independence. He is viewed as the ''metua'' (father) of French Polynesia's independence movement.

Pouvanaa served as a Deputy i ...

for many years.

Faaʻa International Airport

Faaa International Airport (), also known as Tahiti International Airport , is the international airport of French Polynesia, located in the commune of Faʻaʻā, on the island of Tahiti. It is situated southwest of Papeete, the capital city o ...

was opened on Tahiti in 1960.

On 17 July 1974, the French did a nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the performance of nuclear weapons and the effects of their explosion. Nuclear testing is a sensitive political issue. Governments have often performed tests to signal strength. Bec ...

over Mururoa Atoll, codenamed , but the atomic cloud and fallout did not take the direction planned. 42 hours later, the cloud reached Tahiti and the surrounding islands. As many as 111,000 people were affected. Reports showed that some people on Tahiti were exposed to 500 times the maximum allowed level for plutonium.

In 2003, French Polynesia's status was changed to that of an overseas collectivity

The French overseas collectivities ( abbreviated as COM) are first-order administrative divisions of France, like the French regions, but have a semi-autonomous status. The COMs include some former French overseas colonies and other French ...

(''collectivité d'outre-mer''), and in 2004 it was declared an overseas country (''pays d'outre-mer'' or ''POM'').

In 2009, Tauatomo Mairau claimed the Tahitian throne and attempted to re-assert the status of the monarchy in court.

Politics

Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, ; ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and 1986 to 1988, as well as Mayor of Pari ...

said he did not think the majority of Tahitians wanted independence. He would keep an open door to a possible referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

in the future.

Elections for the Assembly of French Polynesia

The Assembly of French Polynesia (, ; Tahitian: ''Te apoʻoraʻa rahi o te fenua Māʻohi'') is the unicameral legislature of French Polynesia, an overseas country of the French Republic. It is located at Place Tarahoi in Papeete, Tahiti. It wa ...

, the Territorial Assembly of French Polynesia, were held on 23 May 2004.

In a surprise result, Oscar Temaru

Oscar Manutahi Temaru (born November 1, 1944) is a Tahitian politician. He has been the president of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France, on five occasions: in 2004, from 2005 to 2006, from 2007 to 2008, in 2009, and from 2011 to ...

's pro-independence progressive coalition, Union for Democracy

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Union ...

, formed a government with a one-seat majority in the 57-seat parliament, defeating the conservative party, Tāhōeraa Huiraatira, led by Gaston Flosse

Gaston Flosse (born 24 June 1931) is a French Polynesian politician who has been President of French Polynesia on five separate occasions. He is currently a member of the Senate of France and has been a French junior minister under Jacques Chirac ...

. On 8 October 2004, Flosse succeeded in passing a censure motion against the government, provoking a crisis. Flosse was removed from office in 2004 but was subsequently re-elected in 2008 after a period of political instability. His main rival Oscar Temaru served as the President of French Polynesia during multiple terms: 2004-2005, 2006-2008, and 2009-2013. He led the left-wing pro-independence party, Union for Democracy (UPLD). Temaru focused on greater autonomy for French Polynesia and calls for independence.

Demographics

The indigenous Tahitians are of Polynesian ancestry and make up 70% of the population alongside Europeans, East Asians (mostlyChinese

Chinese may refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people identified with China, through nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**Han Chinese, East Asian ethnic group native to China.

**'' Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic ...

), and people of mixed heritage, sometimes referred to as ''Demis''.

The places of birth of the 189,517 residents of the island of Tahiti at the 2017 census were the following:

*75.4% were born in Tahiti (up from 71.5% at the 2007 census)

*9.3% in

The places of birth of the 189,517 residents of the island of Tahiti at the 2017 census were the following:

*75.4% were born in Tahiti (up from 71.5% at the 2007 census)

*9.3% in Metropolitan France

Metropolitan France ( or ), also known as European France (), is the area of France which is geographically in Europe and chiefly comprises #Hexagon, the mainland, popularly known as "the Hexagon" ( or ), and Corsica. This collective name for the ...

(down from 10.9% in 2007)

*5.9% elsewhere in the Society Islands

The Society Islands ( , officially ; ) are an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean that includes the major islands of Tahiti, Mo'orea, Moorea, Raiatea, Bora Bora and Huahine. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country ...

(down from 6.4% in 2007)

*2.8% in the Tuamotu-Gambier (down from 3.3% in 2007)

*1.8% in the Marquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands ( ; or ' or ' ; Marquesan language, Marquesan: ' (North Marquesan language, North Marquesan) and ' (South Marquesan language, South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcano, volcanic islands in ...

(down from 2.0% in 2007)

*1.6% in the Austral Islands

The Austral Islands ( officially ''Archipel des Australes;'' ) are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of France, overseas country of the France, French Republic in the Oceania, South Pacific. Geographicall ...

(down from 2.0% in 2007)

*1.3% in the overseas departments and territories of France

Overseas France (, also ) consists of 13 French territories outside Europe, mostly the remnants of the French colonial empire that remained a part of the French state under various statuses after decolonisation. Most are part of the European ...

other than French Polynesia (1.0% in New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

and Wallis and Futuna

Wallis and Futuna, officially the Territory of the Wallis and Futuna Islands (), is a French island territorial collectivity, collectivity in the Oceania, South Pacific, situated between Tuvalu to the northwest, Fiji to the southwest, Tonga t ...

; 0.3% in the other overseas departments and collectivities) (down from 1.6% in 2007)

*0.5% in East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

(same percentage as in 2007)

*0.3% in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

(most of them Pieds-Noirs

The (; ; : ) are an ethno-cultural group of people of French and other European descent who were born in Algeria during the period of French colonial rule from 1830 to 1962. Many of them departed for mainland France during and after the ...

) (down from 0.4% in 2007)

*1.1% in other foreign countries (down from 1.5% in 2007)

Most people from metropolitan France

Metropolitan France ( or ), also known as European France (), is the area of France which is geographically in Europe and chiefly comprises #Hexagon, the mainland, popularly known as "the Hexagon" ( or ), and Corsica. This collective name for the ...

live in Papeete and its suburbs, notably Punaauia, where they made up 16.8% of the population at the 2017 census, and Arue, where they made up 15.9%; these percentages do not include their children born in French Polynesia.

Historical population

Administrative divisions

The island consists of 12communes

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

, which, along with Moorea-Maiao, make up the Windward Islands administrative subdivision

Administrative divisions (also administrative units, administrative regions, subnational entities, or constituent states, as well as many similar generic terms) are geographical areas into which a particular independent sovereign state is divi ...

.

The capital is Papeetē and the largest commune by population is Faaā while Taiarapu-Est has the largest area.

Communes of Tahiti

The following is a list of communes and their subdivisions sorted alphabetically:Economy

Tourism is a significant industry, generating 17% of GDP before the COVID-19 pandemic.Tahitian pearl

The Tahitian pearl (or black pearl) is an organic gem formed from the black lip oyster (''Pinctada margaritifera'').Newman, Renee. ''Pearl Buying Guide''. "Black Pearls." Los Angeles: International Jewelry Publications, c2005, p. 73 These pearls ...

(Black pearl) farming is also a substantial source of revenues, most of the pearls being exported to Japan, Europe and the United States. Tahiti also exports vanilla

Vanilla is a spice derived from orchids of the genus ''Vanilla (genus), Vanilla'', primarily obtained from pods of the flat-leaved vanilla (''Vanilla planifolia, V. planifolia'').

''Vanilla'' is not Autogamy, autogamous, so pollination ...

, fruits, flowers, monoi, fish, copra oil

Coconut oil (or coconut fat) is an edible oil derived from the kernels, meat, and milk of the coconut palm fruit. Coconut oil is a white solid fat below around , and a clear thin liquid oil at higher temperatures. Unrefined varieties have a disti ...

, and noni

''Morinda citrifolia'' is a fruit-bearing tree in the coffee family, Rubiaceae, native to Southeast Asia and Australasia, which was spread across the Pacific by Polynesian sailors. The species is now cultivated throughout the tropics and widel ...

. Tahiti is also home to a single winery, whose vineyards are located on the Rangiroa

Rangiroa ( Tuamotuan for 'vast sky') or Te Kokōta (Cook Islands Māori

Cook Islands Māori is an Eastern Polynesian language that is the official language of the Cook Islands. Cook Islands Māori is closely related to, but distinct from ...

atoll.

Unemployment affects about 15% of the active population, especially women and unqualified young people.

Tahiti's currency, the French Pacific Franc (CFP, also known as XPF), is pegged to the euro

The euro (currency symbol, symbol: euro sign, €; ISO 4217, currency code: EUR) is the official currency of 20 of the Member state of the European Union, member states of the European Union. This group of states is officially known as the ...

at 1 CFP=EUR .0084 (1 EUR=119.48 CFP, approx. 113 CFP to the United States dollar

The United States dollar (Currency symbol, symbol: Dollar sign, $; ISO 4217, currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and International use of the U.S. dollar, several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introdu ...

in November 2024). Hotels and financial institutions offer exchange services.

Sales tax

A sales tax is a tax paid to a governing body for the sales of certain goods and services. Usually laws allow the seller to collect funds for the tax from the consumer at the point of purchase. When a tax on goods or services is paid to a govern ...

in Tahiti is called ''Taxe sur la valeur ajoutée'' (TVA or value added tax

A value-added tax (VAT or goods and services tax (GST), general consumption tax (GCT)) is a consumption tax that is levied on the value added at each stage of a product's production and distribution. VAT is similar to, and is often compared wi ...

(VAT) in English). VAT in 2009 was 10% on tourist services, and 6% on hotels, small boarding houses, food and beverages. VAT on the purchase of goods and products is 16%.

Energy and electricity

French Polynesia imports its petroleum and has no local refinery or production capabilities. Daily consumption of imported oil products was 7,430 barrels in 2012 and 6,100 barrels per day in 2022, according to the US Energy Information Administration. The utility EDT operates hydroelectric plants, solar plants, and a 10 MWh battery to reduce oil demand.Culture

As is mentioned in records of Captain Cook's visits, breadfruit is a staple crop. One main way of preparing it is documented in

As is mentioned in records of Captain Cook's visits, breadfruit is a staple crop. One main way of preparing it is documented in Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

' diaries: after it is very ripe, breadfruit can be buried in leaf-lined pits with weights placed on top of it, to allow it to ferment into a sour paste known as ''mahie''.

Art

Tahitian cultures included an oral tradition that involved the mythology of gods, such asOro

Oro or ORO, meaning gold in Spanish and Italian, may refer to:

Music and dance

* Oro (dance), a Balkan circle dance

* Oro (eagle dance), an eagle dance from Montenegro and Herzegovina

* "Oro" (Mango song), 1984

* "Oro" (Jelena Tomašević son ...

and beliefs, as well as ancient traditions such as tattooing and navigation. The annual Heivā I Tahiti Festival in July is a celebration of traditional culture, dance, music and sports including a long-distance race between the islands of French Polynesia, in modern outrigger canoe

Outrigger boats are various watercraft featuring one or more lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are fastened to one or both sides of the main hull (watercraft), hull. They can range from small dugout (boat), dugout canoes to large ...

s ( vaa).

The Paul Gauguin Museum is dedicated to the life and works of French artist Paul Gauguin

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (; ; 7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903) was a French painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramist, and writer, whose work has been primarily associated with the Post-Impressionist and Symbolist movements. He was also an influ ...

(1848–1903) who resided in Tahiti for years and painted such works as '' Two Tahitian Women'', '' Tahitian Women on the Beach'', and '' Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?''

The Musée de Tahiti et des Îles

The Musée de Tahiti et des Îles ("Museum of Tahiti and the Islands"), Tahitian Te Fare Manaha ("the Museum"), is the national museum of French Polynesia, located in Puna'auia, Tahiti.

History

The museum was founded in 1974 to conserve and re ...

(Museum of Tahiti and the Islands) is in Punaauia. It is an ethnographic

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

museum that was founded in 1974 to conserve and restore Polynesian artefacts and cultural practices.

The Robert Wan Pearl Museum is the world's only museum dedicated to pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

s. The Papeete Market sells local arts and crafts.

Dance

One of the most widely recognised images of the islands is the world-famous Tahitian dance. The '' ōtea'' (sometimes written as ''otea'') is a traditional dance from Tahiti, where the dancers, standing in several rows, execute figures. This dance, easily recognised by its fast hip-shaking and grass skirts, is often confused with the Hawaiianhula

Hula () is a Hawaiian dance form expressing chant (''oli'') or song (Mele (Hawaiian language), ''mele''). It was developed in the Hawaiian Islands by the Native Hawaiians who settled there. The hula dramatizes or portrays the words of the oli ...

, a generally slower, more graceful dance which focuses more on the hands and storytelling than the hips.

The ōtea is one of the few Tahitian men's dances that existed in pre-European times. On the other hand, the ''hura'' (Tahitian vernacular for ''hula''), a dance for women, has disappeared, and the couples' dance '' upaupa'' is likewise gone but may have re-emerged as the tamure

The tāmūrē, or tamouré as popularized in many 1960s recordings, is a dance from Tahiti and the Cook Islands. Usually danced as a group of boys and girls, all dressed in ''more'' (the Tahitian grass skirt, however not made of grass but of t ...

. Nowadays, the ōtea can be danced by men (''ōtea tāne''), by women (''ōtea vahine''), or by both genders (''ōtea āmui'', "united ō"). This dance is accompanied by instruments only, particularly drums; no singing is involved. The drum can be one of the types of the tōere, a laying log of wood with a longitudinal slit, which is struck by one or two sticks. Or it can be the ''pahu'', the ancient Tahitian standing drum covered with a shark skin and struck by the hands or with sticks. The rhythm from the tōere is fast; from the pahu

The term "pahu" is a general word for drum in Hawaiian culture however, there are a variety of them. To fully understand the "pahu" as it pertains to dance, it's important to consider the following explanation.

Since the mid-1800s, the term "h ...

it is slower. A smaller drum, the ''faatete'', can also be used.

The dancers make gestures that re-enact daily occupations of life. For the men the themes can include warfare or sailing, and they may use spears or paddles during such dances.

For women the themes are closer to home or from nature: combing their hair or the flight of a butterfly, for example. More elaborate themes can be chosen, for example, one where the dancers end up portraying a map of Tahiti, highlighting important places. In a proper ōtea the whole dance should be one story on a single theme.

The group dance called aparima is often performed with the dancers dressed in pareo

A pāreu or pareo is a wraparound skirt worn in Tahiti. The term was originally used only for women's skirts, as men wore a loincloth, called a '' maro''. Nowadays the term is used for any cloth worn wrapped around the body by men and women.

T ...

and maro. There are two types of aparima: the ''aparima hīmene'' (sung handdance) and the ''aparima vāvā'' (silent handdance), the latter of which is accompanied by instruments without any singing.

Newer dances include the hivinau and the pāʻōʻā.

Death

The Tahitians believed in the afterlife, a paradise called Rohutu-noanoa. When a Tahitian died, the corpse was wrapped inbarkcloth

Barkcloth or bark cloth is a versatile material that was once common in Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. Barkcloth comes primarily from trees of the family Moraceae, including '' Broussonetia papyrifera'', '' Artocarpus altilis'', '' Artocarpus ...