Stanisław Ulam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

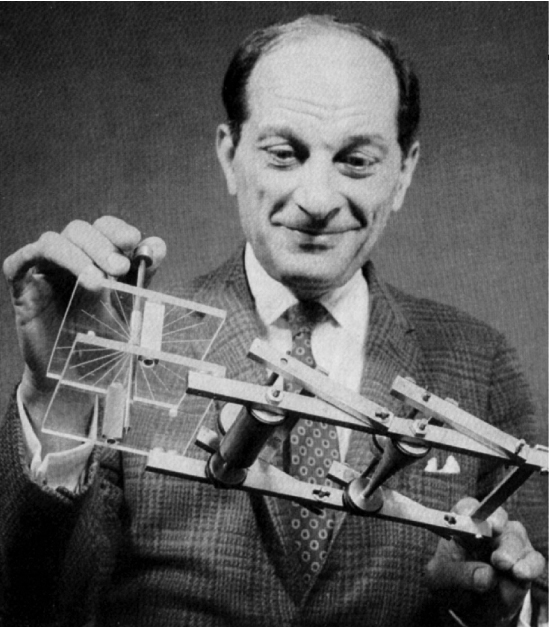

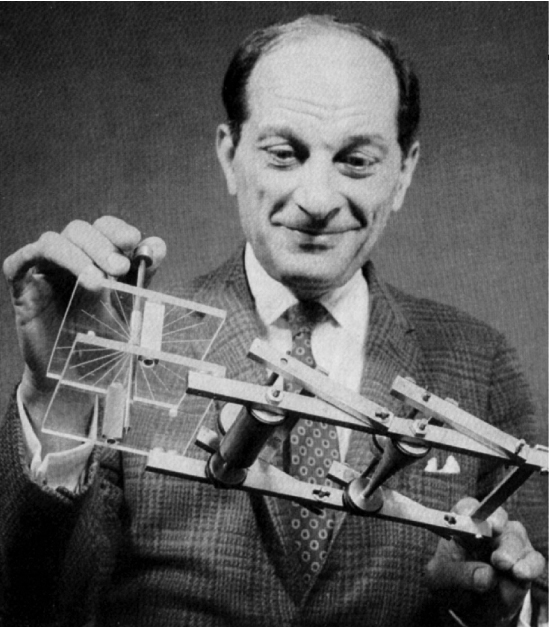

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the

In 1919, Ulam entered Lwów Gymnasium Nr. VII, from which he graduated in 1927. He then studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute. Under the supervision of

In 1919, Ulam entered Lwów Gymnasium Nr. VII, from which he graduated in 1927. He then studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute. Under the supervision of

In early 1943, Ulam asked von Neumann to find him a war job. In October, he received an invitation to join an unidentified project near

In early 1943, Ulam asked von Neumann to find him a war job. In October, he received an invitation to join an unidentified project near

Late in the war, under the sponsorship of von Neumann, Frankel and Metropolis began to carry out calculations on the first general-purpose electronic computer, the

Late in the war, under the sponsorship of von Neumann, Frankel and Metropolis began to carry out calculations on the first general-purpose electronic computer, the

Because the results of calculations based on Teller's concept were discouraging, many scientists believed it could not lead to a successful weapon, while others had moral and economic grounds for not proceeding. Consequently, several senior people of the Manhattan Project opposed development, including Bethe and Oppenheimer. To clarify the situation, Ulam and von Neumann resolved to do new calculations to determine whether Teller's approach was feasible. To carry out these studies, von Neumann decided to use electronic computers: ENIAC at Aberdeen, a new computer,

Because the results of calculations based on Teller's concept were discouraging, many scientists believed it could not lead to a successful weapon, while others had moral and economic grounds for not proceeding. Consequently, several senior people of the Manhattan Project opposed development, including Bethe and Oppenheimer. To clarify the situation, Ulam and von Neumann resolved to do new calculations to determine whether Teller's approach was feasible. To carry out these studies, von Neumann decided to use electronic computers: ENIAC at Aberdeen, a new computer,  In September 1951, after a series of differences with Bradbury and other scientists, Teller resigned from Los Alamos, and returned to the University of Chicago. At about the same time, Ulam went on leave as a visiting professor at Harvard for a semester. Although Teller and Ulam submitted a joint report on their design and jointly applied for a patent on it, they soon became involved in a dispute over who deserved credit. After the war, Bethe returned to

In September 1951, after a series of differences with Bradbury and other scientists, Teller resigned from Los Alamos, and returned to the University of Chicago. At about the same time, Ulam went on leave as a visiting professor at Harvard for a semester. Although Teller and Ulam submitted a joint report on their design and jointly applied for a patent on it, they soon became involved in a dispute over who deserved credit. After the war, Bethe returned to

Starting in 1955, Ulam and

Starting in 1955, Ulam and

During his years at Los Alamos, Ulam was a visiting professor at Harvard from 1951 to 1952,

During his years at Los Alamos, Ulam was a visiting professor at Harvard from 1951 to 1952,

The

The

1979 Audio Interview with Stanislaus Ulam by Martin Sherwin

Voices of the Manhattan Project

1965 Audio Interview with Stanislaus Ulam by Richard Rhodes

Voices of the Manhattan Project * * – 1976 lecture on ''The First International Research Conference on the History of Computing''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ulam, Stanislaw 1909 births 1984 deaths Politicians from Lviv Jews from Galicia (Eastern Europe) People from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria Polish agnostics Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States Polish set theorists Harvard University faculty University of Wisconsin–Madison faculty University of Colorado Boulder faculty University of Colorado Denver faculty University of Florida faculty Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Manhattan Project people People from Los Alamos, New Mexico Jewish American scientists Lwów School of Mathematics Mathematics popularizers Monte Carlo methodologists Cellular automatists Jewish agnostics Lviv Polytechnic alumni Jewish physicists Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery Members of the American Philosophical Society

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, originated the Teller–Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

of thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

s, discovered the concept of the cellular automaton

A cellular automaton (pl. cellular automata, abbrev. CA) is a discrete model of computation studied in automata theory. Cellular automata are also called cellular spaces, tessellation automata, homogeneous structures, cellular structures, tesse ...

, invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion

Nuclear pulse propulsion or external pulsed plasma propulsion is a hypothetical method of spacecraft propulsion that uses nuclear explosions for thrust. It originated as Project ''Orion'' with support from DARPA, after a suggestion by Stanislaw ...

. In pure and applied mathematics

Applied mathematics is the application of mathematical methods by different fields such as physics, engineering, medicine, biology, finance, business, computer science, and industry. Thus, applied mathematics is a combination of mathematical s ...

, he proved some theorems and proposed several conjectures.

Born into a wealthy Polish Jewish

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lon ...

family, Ulam studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute, where he earned his PhD in 1933 under the supervision of Kazimierz Kuratowski

Kazimierz Kuratowski (; 2 February 1896 – 18 June 1980) was a Polish mathematician and logician. He was one of the leading representatives of the Warsaw School of Mathematics.

Biography and studies

Kazimierz Kuratowski was born in Warsaw, (t ...

and Włodzimierz Stożek

Włodzimierz Stożek (23 July 1883 – 3 or 4 July 1941) was a Polish mathematician of the Lwów School of Mathematics.

Head of the Mathematics Faculty on the Lwów University of Technology. He was arrested and murdered together with his two son ...

. In 1935, John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

, whom Ulam had met in Warsaw, invited him to come to the Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States, is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholar ...

in Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

, for a few months. From 1936 to 1939, he spent summers in Poland and academic years at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, where he worked to establish important results regarding ergodic theory

Ergodic theory (Greek: ' "work", ' "way") is a branch of mathematics that studies statistical properties of deterministic dynamical systems; it is the study of ergodicity. In this context, statistical properties means properties which are expres ...

. On 20 August 1939, he sailed for the United States for the last time with his 17-year-old brother Adam Ulam

Adam Bruno Ulam (8 April 1922 – 28 March 2000) was a Polish-American historian of Jewish descent and political scientist at Harvard University. Ulam was one of the world's foremost authorities and top experts in Sovietology and Kremlinology ...

. He became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an educational institution, institution of higher education, higher (or Tertiary education, tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. Universities ty ...

in 1940, and a United States citizen in 1941.

In October 1943, he received an invitation from Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

to join the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

at the secret Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

in New Mexico. There, he worked on the hydrodynamic

In physics and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids— liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including '' aerodynamics'' (the study of air and other gases in motion) a ...

calculations to predict the behavior of the explosive lens

An explosive lens—as used, for example, in nuclear weapons—is a highly specialized shaped charge. In general, it is a device composed of several explosive charges. These charges are arranged and formed with the intent to control the shape ...

es that were needed by an implosion-type weapon. He was assigned to Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

's group, where he worked on Teller's "Super" bomb for Teller and Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

. After the war he left to become an associate professor at the University of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in C ...

, but returned to Los Alamos in 1946 to work on thermonuclear weapons

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

. With the aid of a cadre of female "computers

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation) automatically. Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as programs. These programs ...

", including his wife Françoise Aron Ulam, he found that Teller's "Super" design was unworkable. In January 1951, Ulam and Teller came up with the Teller–Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

, which became the basis for all thermonuclear weapons.

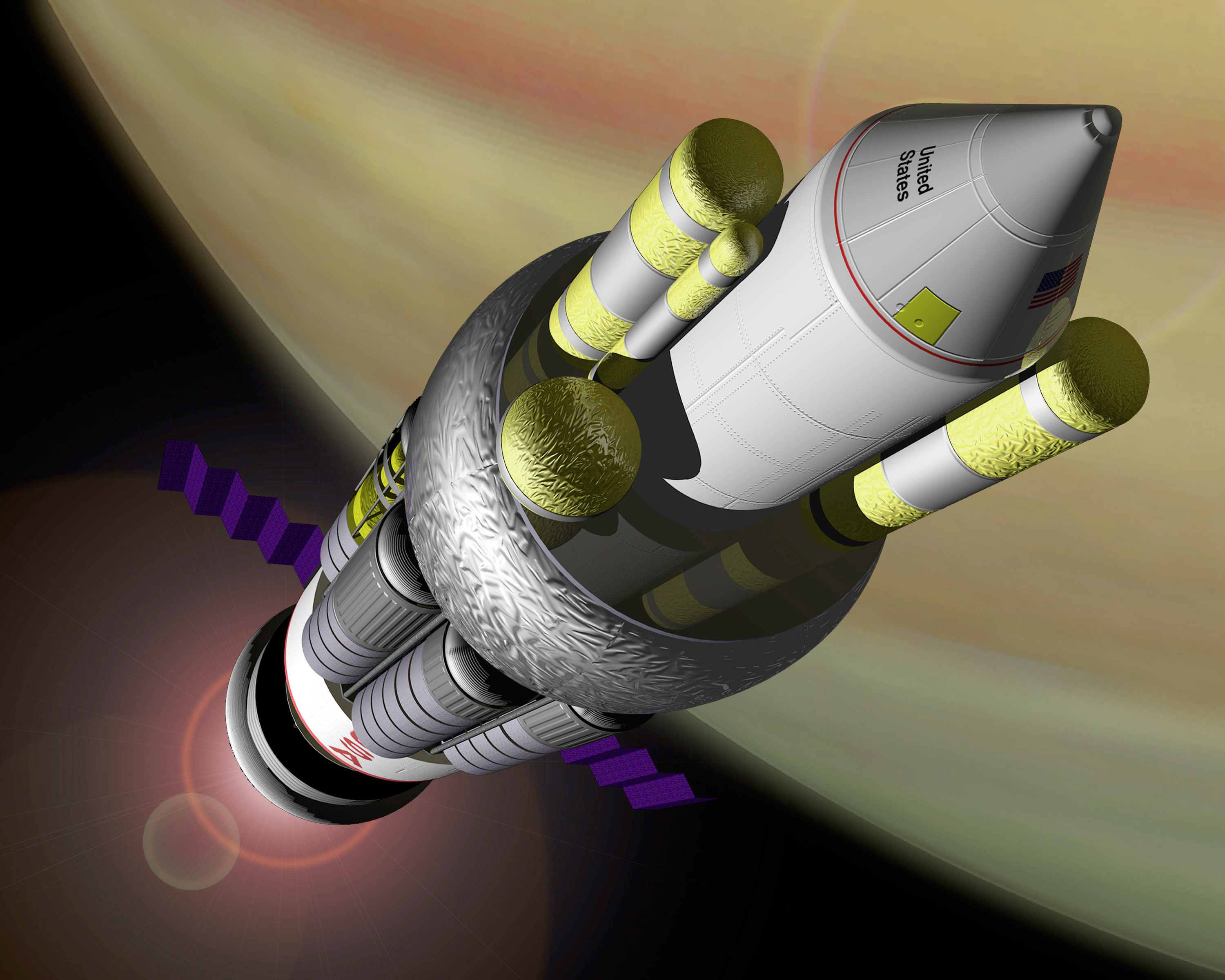

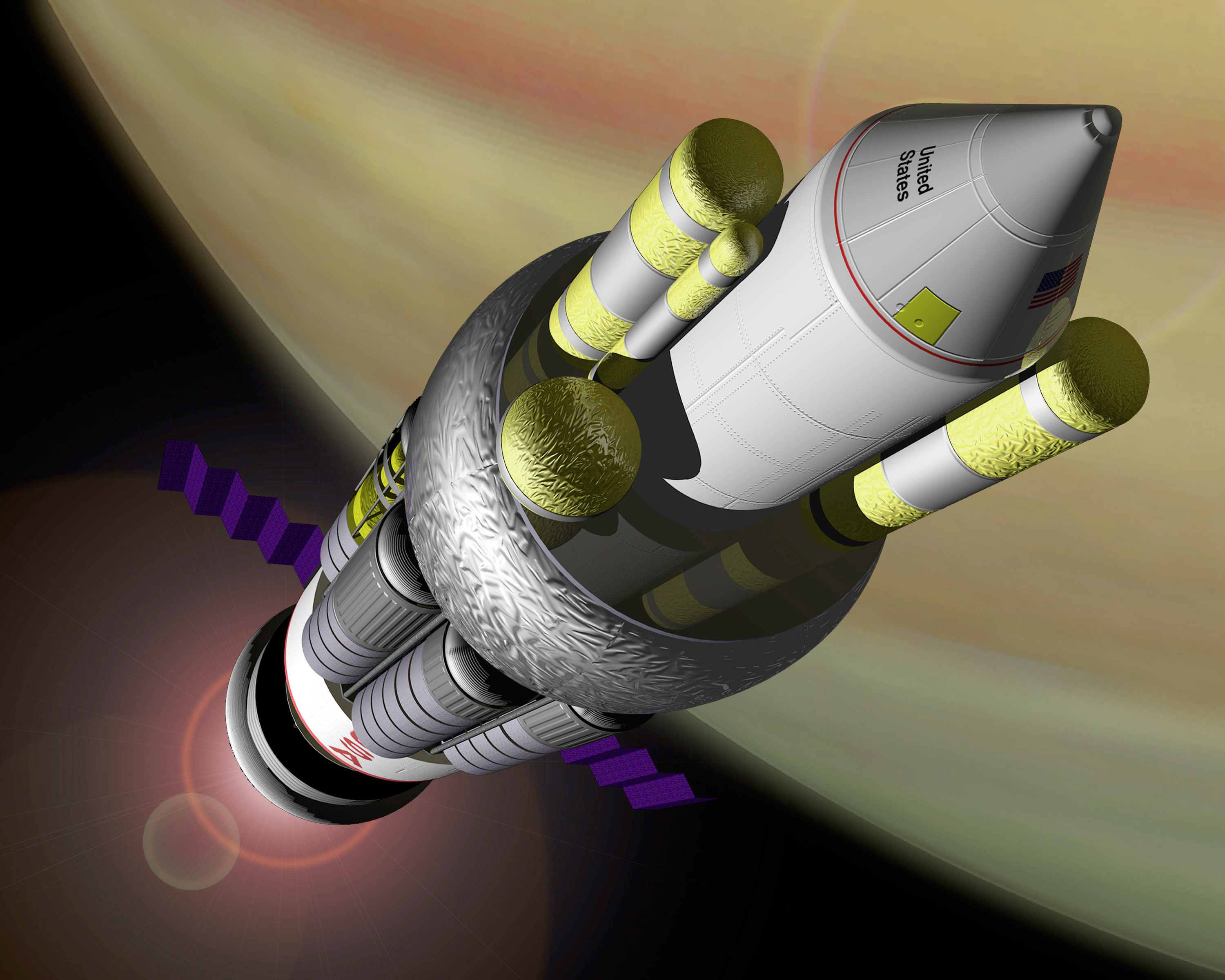

Ulam considered the problem of nuclear propulsion

Nuclear propulsion includes a wide variety of propulsion methods that use some form of nuclear reaction as their primary power source. The idea of using nuclear material for propulsion dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. In 1903 it was ...

of rockets, which was pursued by Project Rover

Project Rover was a United States project to develop a nuclear-thermal rocket that ran from 1955 to 1973 at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory (LASL). It began as a United States Air Force project to develop a nuclear-powered upper stage for ...

, and proposed, as an alternative to Rover's nuclear thermal rocket

A nuclear thermal rocket (NTR) is a type of thermal rocket where the heat from a nuclear reaction, often nuclear fission, replaces the chemical energy of the propellants in a chemical rocket. In an NTR, a working fluid, usually liquid hydrog ...

, to harness small nuclear explosions for propulsion, which became Project Orion. With Fermi, John Pasta

John Robert Pasta (October 22, 1918 – June 5, 1981) was an American computational physicist and computer scientist who is remembered today for the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou experiment, the result of which was much discussed among physic ...

, and Mary Tsingou

Mary Tsingou (married name: Mary Tsingou-Menzel; born October 14, 1928) is an American physicist and mathematician of Greek descent. She was one of the first programmers on the MANIAC computer at Los Alamos National Laboratory and is best known ...

, Ulam studied the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem

In physics, the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem or formerly the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam problem was the apparent paradox in chaos theory that many complicated enough physical systems exhibited almost exactly periodic behavior – called Fermi ...

, which became the inspiration for the field of non-linear science. He is probably best known for realising that electronic computers made it practical to apply statistical methods to functions without known solutions, and as computers have developed, the Monte Carlo method

Monte Carlo methods, or Monte Carlo experiments, are a broad class of computational algorithms that rely on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results. The underlying concept is to use randomness to solve problems that might be determi ...

has become a common and standard approach to many problems.

Poland

Ulam was born inLemberg

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

, Galicia, on 13 April 1909. At this time, Galicia was in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,, ; pl, Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, ; uk, Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; la, Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae also known as ...

of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, which was known to Poles as the Austrian partition

The Austrian Partition ( pl, zabór austriacki) comprise the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired by the Habsburg monarchy during the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century. The three partitions were conduct ...

. In 1918, it became part of the newly restored Poland, the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

, and the city took its Polish name again, Lwów.

The Ulams were a wealthy Polish Jewish

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lon ...

family of bankers, industrialists, and other professionals. Ulam's immediate family was "well-to-do but hardly rich". His father, Józef Ulam, was born in Lwów and was a lawyer, and his mother, Anna (née Auerbach), was born in Stryj. His uncle, Michał Ulam, was an architect, building contractor, and lumber industrialist. From 1916 until 1918, Józef's family lived temporarily in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. After they returned, Lwów became the epicenter of the Polish–Ukrainian War

The Polish–Ukrainian War, from November 1918 to July 1919, was a conflict between the Second Polish Republic and Ukrainian forces (both the West Ukrainian People's Republic and Ukrainian People's Republic). The conflict had its roots in ethn ...

, during which the city experienced a Ukrainian siege.

In 1919, Ulam entered Lwów Gymnasium Nr. VII, from which he graduated in 1927. He then studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute. Under the supervision of

In 1919, Ulam entered Lwów Gymnasium Nr. VII, from which he graduated in 1927. He then studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute. Under the supervision of Kazimierz Kuratowski

Kazimierz Kuratowski (; 2 February 1896 – 18 June 1980) was a Polish mathematician and logician. He was one of the leading representatives of the Warsaw School of Mathematics.

Biography and studies

Kazimierz Kuratowski was born in Warsaw, (t ...

, he received his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree in 1932, and became a Doctor of Science

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

in 1933. At the age of 20, in 1929, he published his first paper ''Concerning Function of Sets'' in the journal ''Fundamenta Mathematicae

''Fundamenta Mathematicae'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal of mathematics with a special focus on the foundations of mathematics, concentrating on set theory, mathematical logic, topology and its interactions with algebra, and dynamical sys ...

''. From 1931 until 1935, he traveled to and studied in Wilno

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

(Vilnius), Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Zurich, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, and Cambridge, England

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge became ...

, where he met G. H. Hardy

Godfrey Harold Hardy (7 February 1877 – 1 December 1947) was an English mathematician, known for his achievements in number theory and mathematical analysis. In biology, he is known for the Hardy–Weinberg principle, a basic principle of pop ...

and Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar.

Along with Stanisław Mazur

Stanisław Mieczysław Mazur (1 January 1905, Lwów – 5 November 1981, Warsaw) was a Polish mathematician and a member of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Mazur made important contributions to geometrical methods in linear and nonlinear functio ...

, Mark Kac

Mark Kac ( ; Polish: ''Marek Kac''; August 3, 1914 – October 26, 1984) was a Polish American mathematician. His main interest was probability theory. His question, " Can one hear the shape of a drum?" set off research into spectral theory, the ...

, Włodzimierz Stożek

Włodzimierz Stożek (23 July 1883 – 3 or 4 July 1941) was a Polish mathematician of the Lwów School of Mathematics.

Head of the Mathematics Faculty on the Lwów University of Technology. He was arrested and murdered together with his two son ...

, Kuratowski, and others, Ulam was a member of the Lwów School of Mathematics

The Lwów school of mathematics ( pl, lwowska szkoła matematyczna) was a group of Polish mathematicians who worked in the interwar period in Lwów, Poland (since 1945 Lviv, Ukraine). The mathematicians often met at the famous Scottish Café to ...

. Its founders were Hugo Steinhaus

Hugo Dyonizy Steinhaus ( ; ; January 14, 1887 – February 25, 1972) was a Polish mathematician and educator. Steinhaus obtained his PhD under David Hilbert at Göttingen University in 1911 and later became a professor at the Jan Kazimierz Un ...

and Stefan Banach

Stefan Banach ( ; 30 March 1892 – 31 August 1945) was a Polish mathematician who is generally considered one of the 20th century's most important and influential mathematicians. He was the founder of modern functional analysis, and an origina ...

, who were professors at the Jan Kazimierz University

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

. Mathematicians of this "school" met for long hours at the Scottish Café

The Scottish Café ( pl, Kawiarnia Szkocka) was a café in Lwów, Poland (now Lviv, Ukraine) where, in the 1930s and 1940s, mathematicians from the Lwów School of Mathematics collaboratively discussed research problems, particularly in functio ...

, where the problems they discussed were collected in the Scottish Book, a thick notebook provided by Banach's wife. Ulam was a major contributor to the book. Of the 193 problems recorded between 1935 and 1941, he contributed 40 problems as a single author, another 11 with Banach and Mazur, and an additional 15 with others. In 1957, he received from Steinhaus a copy of the book, which had survived the war, and translated it into English. In 1981, Ulam's friend R. Daniel Mauldin published an expanded and annotated version.

Move to the United States

In 1935,John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

, whom Ulam had met in Warsaw, invited him to come to the Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States, is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholar ...

in Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

, for a few months. In December of that year, Ulam sailed to the US. At Princeton, he went to lectures and seminars, where he heard Oswald Veblen

Oswald Veblen (June 24, 1880 – August 10, 1960) was an American mathematician, geometer and topologist, whose work found application in atomic physics and the theory of relativity. He proved the Jordan curve theorem in 1905; while this was lon ...

, James Alexander, and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

. During a tea party at von Neumann's house, he encountered G. D. Birkhoff, who suggested that he apply for a position with the Harvard Society of Fellows

The Society of Fellows is a group of scholars selected at the beginnings of their careers by Harvard University for their potential to advance academic wisdom, upon whom are bestowed distinctive opportunities to foster their individual and intell ...

. Following up on Birkhoff's suggestion, Ulam spent summers in Poland and academic years at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

from 1936 to 1939, where he worked with John C. Oxtoby to establish results regarding ergodic theory

Ergodic theory (Greek: ' "work", ' "way") is a branch of mathematics that studies statistical properties of deterministic dynamical systems; it is the study of ergodicity. In this context, statistical properties means properties which are expres ...

. These appeared in Annals of Mathematics

The ''Annals of Mathematics'' is a mathematical journal published every two months by Princeton University and the Institute for Advanced Study.

History

The journal was established as ''The Analyst'' in 1874 and with Joel E. Hendricks as the ...

in 1941. In 1938, Stanislaw's mother Anna hanna Ulam (maiden name Auerbach) died of cancer.

On 20 August 1939, in Gdynia

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

, Józef Ulam, along with his brother Szymon, put his two sons, Stanislaw and 17 year old Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

, on a ship headed for the US. Eleven days later, the Germans invaded Poland. Within two months, the Germans completed their occupation

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

of western Poland, and the Soviets invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

and occupied eastern Poland. Within two years, Józef Ulam and the rest of his family, including Stanislaw's sister Stefania Ulam, were victims of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

, Hugo Steinhaus

Hugo Dyonizy Steinhaus ( ; ; January 14, 1887 – February 25, 1972) was a Polish mathematician and educator. Steinhaus obtained his PhD under David Hilbert at Göttingen University in 1911 and later became a professor at the Jan Kazimierz Un ...

was in hiding, Kazimierz Kuratowski

Kazimierz Kuratowski (; 2 February 1896 – 18 June 1980) was a Polish mathematician and logician. He was one of the leading representatives of the Warsaw School of Mathematics.

Biography and studies

Kazimierz Kuratowski was born in Warsaw, (t ...

was lecturing at the underground university in Warsaw, Włodzimierz Stożek

Włodzimierz Stożek (23 July 1883 – 3 or 4 July 1941) was a Polish mathematician of the Lwów School of Mathematics.

Head of the Mathematics Faculty on the Lwów University of Technology. He was arrested and murdered together with his two son ...

and his two sons had been killed in the massacre of Lwów professors

In July 1941, 25 Polish academics from the city of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine) along with the 25 of their family members were killed by Nazi German occupation forces. By targeting prominent citizens and intellectuals for elimination, the Nazis hop ...

, and the last problem had been recorded in the Scottish Book. Stefan Banach

Stefan Banach ( ; 30 March 1892 – 31 August 1945) was a Polish mathematician who is generally considered one of the 20th century's most important and influential mathematicians. He was the founder of modern functional analysis, and an origina ...

survived the Nazi occupation by feeding lice

Louse ( : lice) is the common name for any member of the clade Phthiraptera, which contains nearly 5,000 species of wingless parasitic insects. Phthiraptera has variously been recognized as an order, infraorder, or a parvorder, as a result o ...

at Rudolf Weigl's typhus research institute. In 1963, Adam Ulam

Adam Bruno Ulam (8 April 1922 – 28 March 2000) was a Polish-American historian of Jewish descent and political scientist at Harvard University. Ulam was one of the world's foremost authorities and top experts in Sovietology and Kremlinology ...

, who had become an eminent kremlinologist at Harvard, received a letter from George Volsky, who hid in Józef Ulam's house after deserting from the Polish army. This reminiscence gave a chilling account of Lwów's chaotic scenes in late 1939. In later life Ulam described himself as "an agnostic. Sometimes I muse deeply on the forces that are for me invisible. When I am almost close to the idea of God, I feel immediately estranged by the horrors of this world, which he seems to tolerate".

In 1940, after being recommended by Birkhoff, Ulam became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an educational institution, institution of higher education, higher (or Tertiary education, tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. Universities ty ...

. Here, he became a United States citizen

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constituti ...

in 1941. That year, he married Françoise Aron. She had been a French exchange student at Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a private liberal arts women's college in South Hadley, Massachusetts. It is the oldest member of the historic Seven Sisters colleges, a group of elite historically women's colleges in the Northeastern United States.

...

, whom he met in Cambridge. They had one daughter, Claire. In Madison, Ulam met his friend and colleague C. J. Everett, with whom he collaborated on a number of papers.

Manhattan Project

In early 1943, Ulam asked von Neumann to find him a war job. In October, he received an invitation to join an unidentified project near

In early 1943, Ulam asked von Neumann to find him a war job. In October, he received an invitation to join an unidentified project near Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe ( ; , Spanish for 'Holy Faith'; tew, Oghá P'o'oge, Tewa for 'white shell water place'; tiw, Hulp'ó'ona, label=Tiwa language, Northern Tiwa; nv, Yootó, Navajo for 'bead + water place') is the capital of the U.S. state of New Mexico. ...

. The letter was signed by Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

, who had been appointed as leader of the theoretical division of Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

by Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

, its scientific director. Knowing nothing of the area, he borrowed a New Mexico guide book. On the checkout card, he found the names of his Wisconsin colleagues, Joan Hinton

Joan Hinton (Chinese name: 寒春, Pinyin: ''Hán Chūn''; 20 October 1921 – 8 June 2010) was a nuclear physicist and one of the few women scientists who worked for the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos. She lived in the People's Republic of C ...

, David Frisch, and Joseph McKibben, all of whom had mysteriously disappeared. This was Ulam's introduction to the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, which was the US's wartime effort to create the atomic bomb.

Hydrodynamical calculations of implosion

A few weeks after Ulam reached Los Alamos in February 1944, the project experienced a crisis. In April,Emilio Segrè

Emilio Gino Segrè (1 February 1905 – 22 April 1989) was an Italian-American physicist and Nobel laureate, who discovered the elements technetium and astatine, and the antiproton, a subatomic antiparticle, for which he was awarded the Nobe ...

discovered that plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

made in reactors would not work in a gun-type plutonium weapon like the " Thin Man", which was being developed in parallel with a uranium weapon, the "Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

" that was dropped on Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

. This problem threatened to waste an enormous investment in new reactors at the Hanford site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. The site has been known by many names, including SiteW a ...

and to make slow uranium isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

the only way to prepare fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be t ...

material suitable for use in bombs. To respond, Oppenheimer implemented, in August, a sweeping reorganization of the laboratory to focus on development of an implosion-type weapon and appointed George Kistiakowsky

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Preside ...

head of the implosion department. He was a professor at Harvard and an expert on precise use of explosives.

The basic concept of implosion is to use chemical explosives to crush a chunk of fissile material into a critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fi ...

, where neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

multiplication leads to a nuclear chain reaction, releasing a large amount of energy. Cylindrical implosive configurations had been studied by Seth Neddermeyer

Seth Henry Neddermeyer (September 16, 1907 – January 29, 1988) was an American physicist who co-discovered the muon, and later championed the Implosion-type nuclear weapon while working on the Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos Laborato ...

, but von Neumann, who had experience with shaped charge

A shaped charge is an explosive charge shaped to form an explosively formed penetrator (EFP) to focus the effect of the explosive's energy. Different types of shaped charges are used for various purposes such as cutting and forming metal, ini ...

s used in armor-piercing ammunition

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate either body armour or vehicle armour.

From the 1860s to 1950s, a major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the thick armour carried on many warsh ...

, was a vocal advocate of spherical implosion driven by explosive lens

An explosive lens—as used, for example, in nuclear weapons—is a highly specialized shaped charge. In general, it is a device composed of several explosive charges. These charges are arranged and formed with the intent to control the shape ...

es. He realized that the symmetry and speed with which implosion compressed the plutonium were critical issues, and enlisted Ulam to help design lens configurations that would provide nearly spherical implosion. Within an implosion, because of enormous pressures and high temperatures, solid materials behave much like fluids. This meant that hydrodynamical calculations were needed to predict and minimize asymmetries that would spoil a nuclear detonation. Of these calculations, Ulam said:

Nevertheless, with the primitive facilities available at the time, Ulam and von Neumann did carry out numerical computations that led to a satisfactory design. This motivated their advocacy of a powerful computational capability at Los Alamos, which began during the war years, continued through the cold war, and still exists. Otto Frisch remembered Ulam as "a brilliant Polish topologist with a charming French wife. At once he told me that he was a pure mathematician who had sunk so low that his latest paper actually contained numbers with decimal points!"

Statistics of branching and multiplicative processes

Even the inherent statistical fluctuations ofneutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

multiplication within a chain reaction

A chain reaction is a sequence of reactions where a reactive product or by-product causes additional reactions to take place. In a chain reaction, positive feedback leads to a self-amplifying chain of events.

Chain reactions are one way that sys ...

have implications with regard to implosion speed and symmetry. In November 1944, David Hawkins and Ulam addressed this problem in a report entitled "Theory of Multiplicative Processes". This report, which invokes probability-generating function In probability theory, the probability generating function of a discrete random variable is a power series representation (the generating function) of the probability mass function of the random variable. Probability generating functions are oft ...

s, is also an early entry in the extensive literature on statistics of branching and multiplicative processes. In 1948, its scope was extended by Ulam and Everett.

Early in the Manhattan project, Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

's attention was focused on the use of reactors to produce plutonium. In September 1944, he arrived at Los Alamos, shortly after breathing life into the first Hanford reactor, which had been poisoned by a xenon isotope. Soon after Fermi's arrival, Teller's "Super" bomb group, of which Ulam was a part, was transferred to a new division headed by Fermi. Fermi and Ulam formed a relationship that became very fruitful after the war.

Post war Los Alamos

In September 1945, Ulam left Los Alamos to become an associate professor at theUniversity of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in C ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

. In January 1946, he suffered an acute attack of encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include seizures, hallucinations, ...

, which put his life in danger, but which was alleviated by emergency brain surgery. During his recuperation, many friends visited, including Nicholas Metropolis

Nicholas Constantine Metropolis (Greek: ; June 11, 1915 – October 17, 1999) was a Greek-American physicist.

Metropolis received his BSc (1937) and PhD in physics (1941, with Robert Mulliken) at the University of Chicago. Shortly afterwards, ...

from Los Alamos and the famous mathematician Paul Erdős

Paul Erdős ( hu, Erdős Pál ; 26 March 1913 – 20 September 1996) was a Hungarian mathematician. He was one of the most prolific mathematicians and producers of mathematical conjectures of the 20th century. pursued and proposed problems in ...

, who remarked: "Stan, you are just like before." This was encouraging, because Ulam was concerned about the state of his mental faculties, for he had lost the ability to speak during the crisis. Another friend, Gian-Carlo Rota

Gian-Carlo Rota (April 27, 1932 – April 18, 1999) was an Italian-American mathematician and philosopher. He spent most of his career at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he worked in combinatorics, functional analysis, pro ...

, asserted in a 1987 article that the attack changed Ulam's personality: afterwards, he turned from rigorous pure mathematics to more speculative conjectures concerning the application of mathematics to physics and biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

; Rota also cites Ulam's former collaborator Paul Stein as noting that Ulam was sloppier in his clothing afterwards, and John Oxtoby as noting that Ulam before the encephalitis could work for hours on end doing calculations, while when Rota worked with him, was reluctant to solve even a quadratic equation. This assertion was not accepted by Françoise Aron Ulam.

By late April 1946, Ulam had recovered enough to attend a secret conference at Los Alamos to discuss thermonuclear weapons

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

. Those in attendance included Ulam, von Neumann, Metropolis, Teller, Stan Frankel

Stanley Phillips Frankel (1919 – May, 1978) was an American computer scientist. He worked in the Manhattan Project and developed various computers as a consultant.

Early life

He was born in Los Angeles, attended graduate school at the Univers ...

, and others. Throughout his participation in the Manhattan Project, Teller's efforts had been directed toward the development of a "super" weapon based on nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles ( neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifest ...

, rather than toward development of a practical fission bomb. After extensive discussion, the participants reached a consensus that his ideas were worthy of further exploration. A few weeks later, Ulam received an offer of a position at Los Alamos from Metropolis and Robert D. Richtmyer

Robert Davis Richtmyer (October 10, 1910 – September 24, 2003) was an American physicist, mathematician, educator, author, and musician.

Biography

Richtmyer was born on October 10, 1910 in Ithaca, New York.

His father was physicist Floyd K. R ...

, the new head of its theoretical division, at a higher salary, and the Ulams returned to Los Alamos.

Monte Carlo method

Late in the war, under the sponsorship of von Neumann, Frankel and Metropolis began to carry out calculations on the first general-purpose electronic computer, the

Late in the war, under the sponsorship of von Neumann, Frankel and Metropolis began to carry out calculations on the first general-purpose electronic computer, the ENIAC

ENIAC (; Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer, completed in 1945. There were other computers that had these features, but the ENIAC had all of them in one packa ...

at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. Shortly after returning to Los Alamos, Ulam participated in a review of results from these calculations. Earlier, while playing solitaire during his recovery from surgery, Ulam had thought about playing hundreds of games to estimate statistically the probability of a successful outcome. With ENIAC in mind, he realized that the availability of computers made such statistical methods very practical. John von Neumann immediately saw the significance of this insight. In March 1947 he proposed a statistical approach to the problem of neutron diffusion in fissionable material. Because Ulam had often mentioned his uncle, Michał Ulam, "who just had to go to Monte Carlo" to gamble, Metropolis dubbed the statistical approach "The Monte Carlo method

Monte Carlo methods, or Monte Carlo experiments, are a broad class of computational algorithms that rely on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results. The underlying concept is to use randomness to solve problems that might be determi ...

". Metropolis and Ulam published the first unclassified paper on the Monte Carlo method in 1949.

Fermi, learning of Ulam's breakthrough, devised an analog computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computer that uses the continuous variation aspect of physical phenomena such as electrical, mechanical, or hydraulic quantities (''analog signals'') to model the problem being solved. In c ...

known as the Monte Carlo trolley, later dubbed the FERMIAC

The Monte Carlo trolley, or FERMIAC, was an analog computer invented by physicist Enrico Fermi to aid in his studies of neutron transport.

Operation

The FERMIAC employed the Monte Carlo method to model neutron transport in various types of n ...

. The device performed a mechanical simulation of random diffusion of neutrons. As computers improved in speed and programmability, these methods became more useful. In particular, many Monte Carlo calculations carried out on modern massively parallel

Massively parallel is the term for using a large number of computer processors (or separate computers) to simultaneously perform a set of coordinated computations in parallel. GPUs are massively parallel architecture with tens of thousands of t ...

supercomputer

A supercomputer is a computer with a high level of performance as compared to a general-purpose computer. The performance of a supercomputer is commonly measured in floating-point operations per second ( FLOPS) instead of million instructions ...

s are embarrassingly parallel

In parallel computing, an embarrassingly parallel workload or problem (also called embarrassingly parallelizable, perfectly parallel, delightfully parallel or pleasingly parallel) is one where little or no effort is needed to separate the problem ...

applications, whose results can be very accurate.

Teller–Ulam design

On 29 August 1949, theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

tested its first fission bomb, the RDS-1

The RDS-1 (russian: РДС-1), also known as Izdeliye 501 (device 501) and First Lightning (), was the nuclear bomb used in the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test. The United States assigned it the code-name Joe-1, in reference to Joseph ...

. Created under the supervision of Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolsheviks ...

, who sought to duplicate the US effort, this weapon was nearly identical to Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

, for its design was based on information provided by spies Klaus Fuchs, Theodore Hall

Theodore Alvin Hall (October 20, 1925 – November 1, 1999) was an American physicist and an atomic spy for the Soviet Union, who, during his work on United States efforts to develop the first and second atomic bombs during World War II ...

, and David Greenglass

David Greenglass (March 2, 1922 – July 1, 2014) was an atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked on the Manhattan Project. He was briefly stationed at the Clinton Engineer Works uranium enrichment facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and then ...

. In response, on 31 January 1950, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

announced a crash program to develop a fusion bomb.

To advocate an aggressive development program, Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

and Luis Alvarez came to Los Alamos, where they conferred with Norris Bradbury

Norris Edwin Bradbury (May 30, 1909 – August 20, 1997), was an American physicist who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbur ...

, the laboratory director, and with George Gamow

George Gamow (March 4, 1904 – August 19, 1968), born Georgiy Antonovich Gamov ( uk, Георгій Антонович Гамов, russian: Георгий Антонович Гамов), was a Russian-born Soviet and American polymath, theoret ...

, Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

, and Ulam. Soon, these three became members of a short-lived committee appointed by Bradbury to study the problem, with Teller as chairman. At this time, research on the use of a fission weapon to create a fusion reaction

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles (neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifeste ...

had been ongoing since 1942, but the design was still essentially the one originally proposed by Teller. His concept was to put tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus o ...

and/or deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

in close proximity to a fission bomb, with the hope that the heat and intense flux of neutrons released when the bomb exploded, would ignite a self-sustaining fusion reaction

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles (neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifeste ...

. Reactions of these isotopes of hydrogen

Hydrogen (1H) has three naturally occurring isotopes, sometimes denoted , , and . and are stable, while has a half-life of years. Heavier isotopes also exist, all of which are synthetic and have a half-life of less than one zeptosecond (10� ...

are of interest because the energy per unit mass of fuel released by their fusion is much larger than that from fission of heavy nuclei.

Because the results of calculations based on Teller's concept were discouraging, many scientists believed it could not lead to a successful weapon, while others had moral and economic grounds for not proceeding. Consequently, several senior people of the Manhattan Project opposed development, including Bethe and Oppenheimer. To clarify the situation, Ulam and von Neumann resolved to do new calculations to determine whether Teller's approach was feasible. To carry out these studies, von Neumann decided to use electronic computers: ENIAC at Aberdeen, a new computer,

Because the results of calculations based on Teller's concept were discouraging, many scientists believed it could not lead to a successful weapon, while others had moral and economic grounds for not proceeding. Consequently, several senior people of the Manhattan Project opposed development, including Bethe and Oppenheimer. To clarify the situation, Ulam and von Neumann resolved to do new calculations to determine whether Teller's approach was feasible. To carry out these studies, von Neumann decided to use electronic computers: ENIAC at Aberdeen, a new computer, MANIAC

Maniac (from Greek μανιακός, ''maniakos'') is a pejorative for an individual who experiences the mood known as mania. In common usage, it is also an insult for someone involved in reckless behavior.

Maniac may also refer to:

Film

* ' ...

, at Princeton, and its twin, which was under construction at Los Alamos. Ulam enlisted Everett to follow a completely different approach, one guided by physical intuition. Françoise Ulam was one of a cadre of women "computers

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation) automatically. Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as programs. These programs ...

" who carried out laborious and extensive computations of thermonuclear scenarios on mechanical calculator

A mechanical calculator, or calculating machine, is a mechanical device used to perform the basic operations of arithmetic automatically, or (historically) a simulation such as an analog computer or a slide rule. Most mechanical calculators we ...

s, supplemented and confirmed by Everett's slide rule

The slide rule is a mechanical analog computer which is used primarily for multiplication and division, and for functions such as exponents, roots, logarithms, and trigonometry. It is not typically designed for addition or subtraction, which ...

. Ulam and Fermi collaborated on further analysis of these scenarios. The results showed that, in workable configurations, a thermonuclear reaction would not ignite, and if ignited, it would not be self-sustaining. Ulam had used his expertise in combinatorics

Combinatorics is an area of mathematics primarily concerned with counting, both as a means and an end in obtaining results, and certain properties of finite structures. It is closely related to many other areas of mathematics and has many appl ...

to analyze the chain reaction in deuterium, which was much more complicated than the ones in uranium and plutonium, and he concluded that no self-sustaining chain reaction would take place at the (low) densities that Teller was considering. In late 1950, these conclusions were confirmed by von Neumann's results.

In January 1951, Ulam had another idea: to channel the mechanical shock of a nuclear explosion so as to compress the fusion fuel. On the recommendation of his wife, Ulam discussed this idea with Bradbury and Mark before he told Teller about it. Almost immediately, Teller saw its merit, but noted that soft X-rays

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nbs ...

from the fission bomb would compress the thermonuclear fuel more strongly than mechanical shock and suggested ways to enhance this effect. On 9 March 1951, Teller and Ulam submitted a joint report describing these innovations. A few weeks later, Teller suggested placing a fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be t ...

rod or cylinder at the center of the fusion fuel. The detonation of this "spark plug" would help to initiate and enhance the fusion reaction. The design based on these ideas, called staged radiation implosion, has become the standard way to build thermonuclear weapons. It is often described as the "Teller–Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

".

In September 1951, after a series of differences with Bradbury and other scientists, Teller resigned from Los Alamos, and returned to the University of Chicago. At about the same time, Ulam went on leave as a visiting professor at Harvard for a semester. Although Teller and Ulam submitted a joint report on their design and jointly applied for a patent on it, they soon became involved in a dispute over who deserved credit. After the war, Bethe returned to

In September 1951, after a series of differences with Bradbury and other scientists, Teller resigned from Los Alamos, and returned to the University of Chicago. At about the same time, Ulam went on leave as a visiting professor at Harvard for a semester. Although Teller and Ulam submitted a joint report on their design and jointly applied for a patent on it, they soon became involved in a dispute over who deserved credit. After the war, Bethe returned to Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

, but he was deeply involved in the development of thermonuclear weapons as a consultant. In 1954, he wrote an article on the history of the H-bomb, which presents his opinion that both men contributed very significantly to the breakthrough. This balanced view is shared by others who were involved, including Mark and Fermi, but Teller persistently attempted to downplay Ulam's role. "After the H-bomb was made," Bethe recalled, "reporters started to call Teller the father of the H-bomb. For the sake of history, I think it is more precise to say that Ulam is the father, because he provided the seed, and Teller is the mother, because he remained with the child. As for me, I guess I am the midwife."

With the basic fusion reactions confirmed, and with a feasible design in hand, there was nothing to prevent Los Alamos from testing a thermonuclear device. On 1 November 1952, the first thermonuclear explosion occurred when Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear device, in which part of the explosive yield comes from nuclear fusion.

Ivy Mike was detonated on November 1, 1952, by the United States on the island of Elugelab in ...

was detonated on Enewetak Atoll, within the US Pacific Proving Grounds

The Pacific Proving Grounds was the name given by the United States government to a number of sites in the Marshall Islands and a few other sites in the Pacific Ocean at which it conducted nuclear testing between 1946 and 1962. The U.S. tested a ...

. This device, which used liquid deuterium as its fusion fuel, was immense and utterly unusable as a weapon. Nevertheless, its success validated the Teller–Ulam design, and stimulated intensive development of practical weapons.

Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem

When Ulam returned to Los Alamos, his attention turned away from weapon design and toward the use of computers to investigate problems in physics and mathematics. WithJohn Pasta

John Robert Pasta (October 22, 1918 – June 5, 1981) was an American computational physicist and computer scientist who is remembered today for the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou experiment, the result of which was much discussed among physic ...

, who helped Metropolis to bring MANIAC on line in March 1952, he explored these ideas in a report "Heuristic Studies in Problems of Mathematical Physics on High Speed Computing Machines", which was submitted on 9 June 1953. It treated several problems that cannot be addressed within the framework of traditional analytic methods: billowing of fluids, rotational motion in gravitating systems, magnetic lines of force, and hydrodynamic instabilities.

Soon, Pasta and Ulam became experienced with electronic computation on MANIAC, and by this time, Enrico Fermi had settled into a routine of spending academic years at the University of Chicago and summers at Los Alamos. During these summer visits, Pasta, Ulam, and Mary Tsingou

Mary Tsingou (married name: Mary Tsingou-Menzel; born October 14, 1928) is an American physicist and mathematician of Greek descent. She was one of the first programmers on the MANIAC computer at Los Alamos National Laboratory and is best known ...

, a programmer in the MANIAC group, joined him to study a variation of the classic problem of a string of masses held together by springs that exert forces linearly proportional to their displacement from equilibrium. Fermi proposed to add to this force a nonlinear component, which could be chosen to be proportional to either the square or cube of the displacement, or to a more complicated "broken linear" function. This addition is the key element of the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem

In physics, the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem or formerly the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam problem was the apparent paradox in chaos theory that many complicated enough physical systems exhibited almost exactly periodic behavior – called Fermi ...

, which is often designated by the abbreviation FPUT.

A classical spring system can be described in terms of vibrational modes, which are analogous to the harmonics that occur on a stretched violin string. If the system starts in a particular mode, vibrations in other modes do not develop. With the nonlinear component, Fermi expected energy in one mode to transfer gradually to other modes, and eventually, to be distributed equally among all modes. This is roughly what began to happen shortly after the system was initialized with all its energy in the lowest mode, but much later, essentially all the energy periodically reappeared in the lowest mode. This behavior is very different from the expected equipartition of energy

In classical statistical mechanics, the equipartition theorem relates the temperature of a system to its average energies. The equipartition theorem is also known as the law of equipartition, equipartition of energy, or simply equipartition. ...

. It remained mysterious until 1965, when Kruskal and Zabusky showed that, after appropriate mathematical transformations, the system can be described by the Korteweg–de Vries equation, which is the prototype of nonlinear partial differential equations

In mathematics, a partial differential equation (PDE) is an equation which imposes relations between the various partial derivatives of a multivariable function.

The function is often thought of as an "unknown" to be solved for, similarly to ...

that have soliton

In mathematics and physics, a soliton or solitary wave is a self-reinforcing wave packet that maintains its shape while it propagates at a constant velocity. Solitons are caused by a cancellation of nonlinear and dispersive effects in the medium ...

solutions. This means that FPUT behavior can be understood in terms of solitons.

Nuclear propulsion

Starting in 1955, Ulam and

Starting in 1955, Ulam and Frederick Reines

Frederick Reines ( ; March 16, 1918 – August 26, 1998) was an American physicist. He was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physics for his co-detection of the neutrino with Clyde Cowan in the neutrino experiment. He may be the only scientist in ...

considered nuclear propulsion

Nuclear propulsion includes a wide variety of propulsion methods that use some form of nuclear reaction as their primary power source. The idea of using nuclear material for propulsion dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. In 1903 it was ...

of aircraft and rockets. This is an attractive possibility, because the nuclear energy per unit mass of fuel is a million times greater than that available from chemicals. From 1955 to 1972, their ideas were pursued during Project Rover

Project Rover was a United States project to develop a nuclear-thermal rocket that ran from 1955 to 1973 at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory (LASL). It began as a United States Air Force project to develop a nuclear-powered upper stage for ...

, which explored the use of nuclear reactors to power rockets. In response to a question by Senator John O. Pastore at a congressional committee hearing on "Outer Space Propulsion by Nuclear Energy", on January 22, 1958, Ulam replied that "the future as a whole of mankind is to some extent involved inexorably now with going outside the globe."

Ulam and C. J. Everett also proposed, in contrast to Rover's continuous heating of rocket exhaust, to harness small nuclear explosions for propulsion. Project Orion was a study of this idea. It began in 1958 and ended in 1965, after the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

of 1963 banned nuclear weapons tests in the atmosphere and in space. Work on this project was spearheaded by physicist Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was an English-American theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrices, mathematical formulation of quantum m ...

, who commented on the decision to end Orion in his article, "Death of a Project".

Bradbury appointed Ulam and John H. Manley as research advisors to the laboratory director in 1957. These newly created positions were on the same administrative level as division leaders, and Ulam held his until he retired from Los Alamos. In this capacity, he was able to influence and guide programs in many divisions: theoretical, physics, chemistry, metallurgy, weapons, health, Rover, and others.

In addition to these activities, Ulam continued to publish technical reports and research papers. One of these introduced the Fermi–Ulam model

The Fermi–Ulam model (FUM) is a dynamical system that was introduced by Poland, Polish mathematician Stanislaw Ulam in 1961.

FUM is a variant of Enrico Fermi's primary work on acceleration of cosmic rays, namely Fermi acceleration. The syste ...

, an extension of Fermi's theory of the acceleration of cosmic rays. Another, with Paul Stein and Mary Tsingou

Mary Tsingou (married name: Mary Tsingou-Menzel; born October 14, 1928) is an American physicist and mathematician of Greek descent. She was one of the first programmers on the MANIAC computer at Los Alamos National Laboratory and is best known ...

, titled "Quadratic Transformations", was an early investigation of chaos theory

Chaos theory is an interdisciplinary area of scientific study and branch of mathematics focused on underlying patterns and deterministic laws of dynamical systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions, and were once thought to have co ...

and is considered the first published use of the phrase "chaotic behavior

Chaos theory is an interdisciplinary area of scientific study and branch of mathematics focused on underlying patterns and deterministic laws of dynamical systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions, and were once thought to have c ...

".

Return to academia

During his years at Los Alamos, Ulam was a visiting professor at Harvard from 1951 to 1952,

During his years at Los Alamos, Ulam was a visiting professor at Harvard from 1951 to 1952, MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the m ...

from 1956 to 1957, the University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego or colloquially, UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Insti ...

, in 1963, and the University of Colorado at Boulder

The University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder, CU, or Colorado) is a public research university in Boulder, Colorado. Founded in 1876, five months before Colorado became a state, it is the flagship university of the University of Colorado sys ...

from 1961 to 1962 and 1965 to 1967. In 1967, the last of these positions became permanent, when Ulam was appointed Professor and Chairman of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Colorado. He kept a residence in Santa Fe, which made it convenient to spend summers at Los Alamos as a consultant. He was an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

, the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

, and the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

In Colorado, where he rejoined his friends Gamow, Richtmyer, and Hawkins, Ulam's research interests turned toward biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

. In 1968, recognizing this emphasis, the University of Colorado School of Medicine

The University of Colorado School of Medicine is the medical school of the University of Colorado system. It is located at the Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, Colorado, one of the four University of Colorado campuses, six miles east of downtow ...

appointed Ulam as Professor of Biomathematics, and he held this position until his death. With his Los Alamos colleague Robert Schrandt he published a report, "Some Elementary Attempts at Numerical Modeling of Problems Concerning Rates of Evolutionary Processes", which applied his earlier ideas on branching processes to evolution. Another, report, with William Beyer, Temple F. Smith

Temple Ferris Smith (born March 7, 1939) is an emeritus professor in biomedical engineering who helped to develop the Smith-Waterman algorithm with Michael Waterman in 1981. The Smith-Waterman algorithm serves as the basis for multi sequence comp ...

, and M. L. Stein, titled "Metrics in Biology", introduced new ideas about numerical taxonomy and evolutionary distances.

When he retired from Colorado in 1975, Ulam began to spend winter semesters at the University of Florida

The University of Florida (Florida or UF) is a public land-grant research university in Gainesville, Florida. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida, traces its origins to 1853, and has operated continuously on its ...

, where he was a graduate research professor. Except for sabbaticals at the University of California, Davis