Spallanzani on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

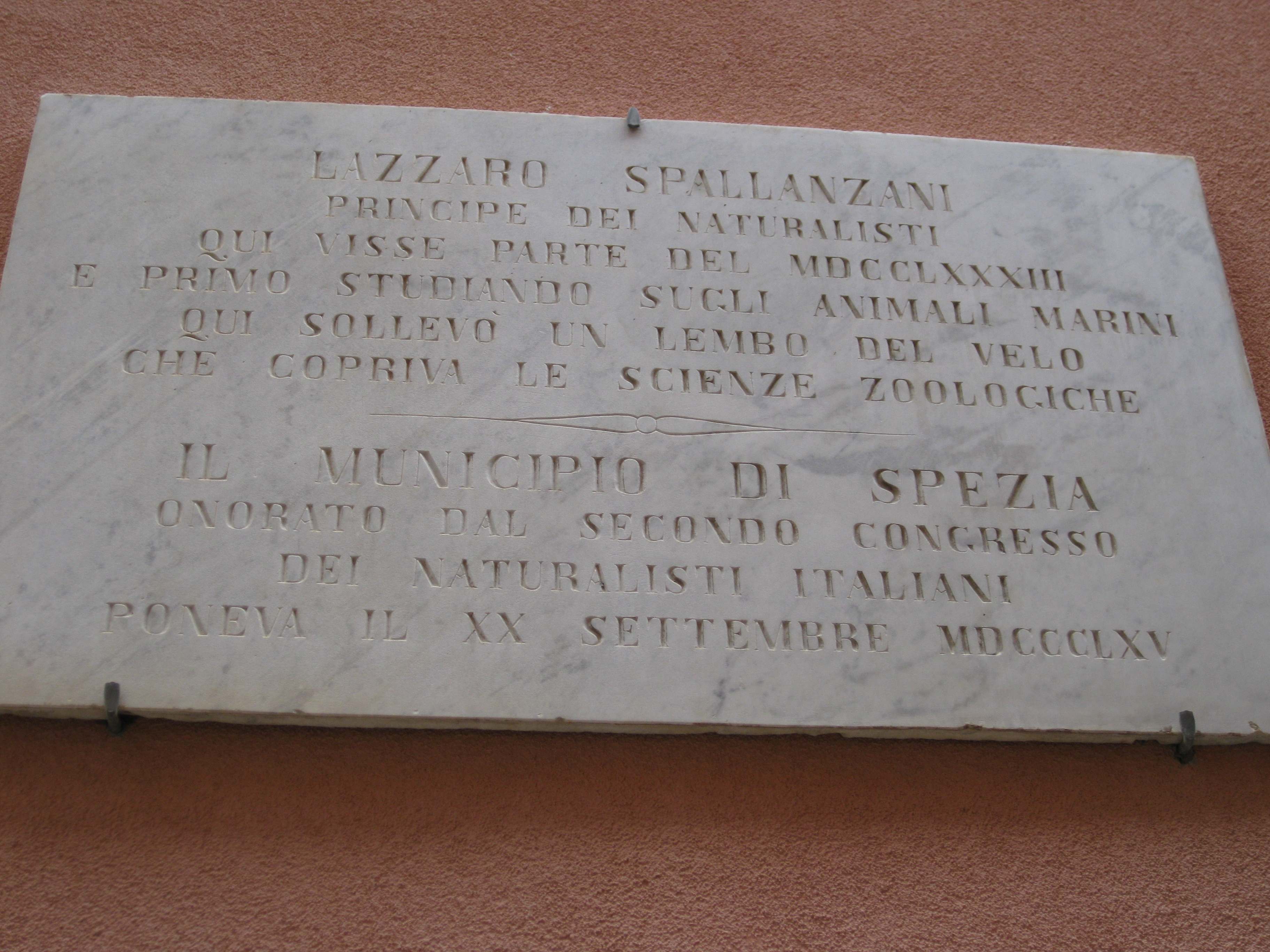

Lazzaro Spallanzani (; 12 January 1729 – 11 February 1799) was an Italian

Spallanzani was born in

Spallanzani was born in

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Page describing, with pictures, some of Lazzaro Spallanzani's memories Official site of "Centro Studi Lazzaro Spallanzani" (Scandiano)Zoologica

Guide to the Lazzaro Spallanzani Papers 1768-1793

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Spallanzani, Lazzaro 1729 births 1799 deaths People from Scandiano 18th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Catholic clergy scientists Italian biologists Italian entomologists Deaths from cancer in Lombardy Deaths from bladder cancer Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Italian physiologists

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priest (for which he was nicknamed Abbé Spallanzani), biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

and physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical a ...

who made important contributions to the experimental study of bodily functions, animal reproduction, and animal echolocation

Echolocation, also called bio sonar, is a biological sonar used by several animal species.

Echolocating animals emit calls out to the environment

and listen to the echoes of those calls that return from various objects near them. They use these ...

. His research on biogenesis

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise ...

paved the way for the downfall of the theory of spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise fr ...

, a prevailing idea at the time that organisms develop from inanimate matters, though the final death blow to the idea was dealt by French scientist Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

a century later.

His most important works were summed up in his book ''Experiencias Para Servir a La Historia de La Generación De Animales y Plantas'' (''Experiences to Serve to the History of the Generation of Animals and Plants''), published in 1786. Among his contributions were experimental demonstrations of fertilisation

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

between ova and spermatozoa, and ''in vitro'' fertilisation''.''

Biography

Scandiano

Scandiano ( Reggiano: ) is a town and ''comune'' in Emilia-Romagna, in the northeast part of the country of Italy, near the city of Reggio nell'Emilia and the Secchia river. It had a population of 25,663 as of 31 December 2016.

History

The cur ...

in the modern province of Reggio Emilia

The Province of Reggio Emilia ( it, Provincia di Reggio nell'Emilia, Emilian: ''pruvînsa ed Rèz'') is one of the nine provinces of the Italian Region of Emilia-Romagna. The capital city, which is the most densely populated comune in the provin ...

to Gianniccolo Spallanzani and Lucia Zigliani. His father, a lawyer by profession, was not impressed with young Spallanzani who spent more time with small animals than studies. With financial support from Vallisnieri Foundation, his father enrolled him to the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

Seminary at age 15. When he was asked to join the order, he refused. Persuaded by his father and with the help of Monsignor Castelvetro, the Bishop of Reggio, he studied law at the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna ( it, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, UNIBO) is a public research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (''studiorum''), it is the oldest university in continuo ...

, which he gave up soon and turned to science. Here, his famous kinswoman, Laura Bassi

Laura Maria Caterina Bassi Veratti (29 October 1711 – 20 February 1778) was an Italian physicist and academic. Recognized and depicted as "Minerva" (goddess of wisdom), she was the first woman to have a doctorate in science, and the second wo ...

, was professor of physics and it is to her influence that his scientific impulse has been usually attributed. With her he studied natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

and mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, and gave also great attention to languages, both ancient and modern, but soon abandoned them. It took him a good friend Antonio Vallisnieri jr. to convince his father to drop law as a career and took up academics instead.

In 1754, at the age of 25, soon after he was ordained he became professor of logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

, metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

in the University of Reggio. In 1763, he was moved to the University of Modena, where he continued to teach with great assiduity and success, but devoted his whole leisure to natural science. There he also served as a priest of the Congregation Beata Vergine and S. Carlo. He declined many offers from other Italian universities and from St Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

until 1768, when he accepted the invitation of Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

to the chair of natural history in the University of Pavia

The University of Pavia ( it, Università degli Studi di Pavia, UNIPV or ''Università di Pavia''; la, Alma Ticinensis Universitas) is a university located in Pavia, Lombardy, Italy. There was evidence of teaching as early as 1361, making it one ...

, which was then being reorganized. He also became director of the museum, which he greatly enriched by the collections of his many journeys along the shores of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. In June 1768 Spallanzani was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

and in 1775 was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences ( sv, Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien) is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special ...

.

In 1785 he was invited to University of Padua

The University of Padua ( it, Università degli Studi di Padova, UNIPD) is an Italian university located in the city of Padua, region of Veneto, northern Italy. The University of Padua was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from B ...

, but to retain his services his sovereign doubled his salary and allowed him leave of absence for a visit to Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

where he remained nearly a year and made many observations, among which may be noted those of a copper mine in Chalki

Halki ( el, Χάλκη; alternatively ''Chalce'' or ''Chalki'') is a Greek island and municipality in the Dodecanese archipelago in the Aegean Sea, some west of Rhodes. With an area of , it is the smallest inhabited island of the Dodecanese. It ...

and of an iron mine at Principi. His return home was almost a triumphal progress: at Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

he was cordially received by Joseph II

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 un ...

and on reaching Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the capit ...

he was met with acclamations outside the city gates by the students of the university. During the following year his students exceeded five hundred. While he was travelling in the Balkans and to Constantinople, his integrity in the management of the museum was called in question (he was accused of the theft of specimens from the University's collection to add to his own cabinet of curiosities), with letters written across Europe to damage Spallanzani's reputation. A judicial investigation speedily cleared his honour to the satisfaction of some of his accusers. But Spallanzani got his revenge on his principal accuser, a jealous colleague, by planting a fake specimen of a composite "species". When his colleague published the remarkable specimen Spallanzani revealed the joke, resulting in wide ridicule and humiliation.

In 1796, Spallanzani received an offer for professor at the National Museum of Natural History, France

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loc ...

in Paris, but declined due to his age. He died from bladder cancer on 12 February 1799, in Pavia. After his death, his bladder was removed for study by his colleagues, after which it was placed on public display in a museum in Pavia, where it remains to this day.

His indefatigable exertions as a traveller, his skill and good fortune as a collector, his brilliance as a teacher and expositor, and his keenness as a controversialist no doubt aid largely in accounting for Spallanzani's exceptional fame among his contemporaries; his letters account for his close relationships with many famed scholars and philosophers, like Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste.

His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including two prominent Fr ...

, Lavoisier, and Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

. Yet greater qualities were by no means lacking. His life was one of incessant eager questioning of nature on all sides, and his many and varied works all bear the stamp of a fresh and original genius, capable of stating and solving problems in all departments of science—at one time finding the true explanation of stone skipping

Stone skipping and stone skimming are considered related but distinct activities: both refer to the art of throwing a flat stone across the water in such a way (usually sidearm) that it bounces off the surface. The objective of "skipping" is t ...

(formerly attributed to the elasticity of water) and at another helping to lay the foundations of our modern volcanology

Volcanology (also spelled vulcanology) is the study of volcanoes, lava, magma and related geological, geophysical and geochemical phenomena (volcanism). The term ''volcanology'' is derived from the Latin word ''vulcan''. Vulcan was the anci ...

and meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not ...

.

Scientific contributions

Spontaneous generation

Spallanzani's first scientific work was in 1765 ''Saggio di osservazioni microscopiche concernenti il sistema della generazione de' signori di Needham, e Buffon'' (''Essay on microscopic observations regarding the generation system of Messrs. Needham and Buffon'') which was the first systematic rebuttal of the theory of thespontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise fr ...

. At the time, the microscope was already available to researchers, and using it, the proponents of the theory, Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis

Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (; ; 1698 – 27 July 1759) was a French mathematician, philosopher and man of letters. He became the Director of the Académie des Sciences, and the first President of the Prussian Academy of Science, at the ...

, Buffon and John Needham

John Turberville Needham FRS (10 September 1713 – 30 December 1781) was an English biologist and Roman Catholic priest.

He was first exposed to natural philosophy while in seminary school and later published a paper which, while the subjec ...

, came to the conclusion that there is a life-generating force inherent to certain kinds of inorganic matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic partic ...

that causes living microbes to create themselves if given sufficient time. Spallanzani's experiment showed that it is not an inherent feature of matter, and that it can be destroyed by an hour of boiling. As the microbes did not re-appear as long as the material was hermetically sealed, he proposed that microbes move through the air and that they could be killed through boiling. Needham argued that experiments destroyed the "vegetative force" that was required for spontaneous generation to occur. Spallanzani paved the way for research by Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

, who defeated the theory of spontaneous generation almost a century later.

Digestion

In his work ''Dissertationi di fisica animale e vegetale'' (''Dissertation on the physiology of animals and vegetables'', in 2 volumes, 1780), Spallanzani was the first to explain the process of digestion in animals. Here he first interpreted the process ofdigestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

, which he proved to be no mere mechanical process of trituration

Trituration (Latin, ''grinding'') is the name of several different methods used to process materials. In one sense, it is a form of comminution (reducing the particle size of a substance). In another sense, it is the production of a homogeneous pow ...

– that is, of grinding up the food – but one of actual chemical solution

In chemistry, a solution is a special type of homogeneous mixture composed of two or more substances. In such a mixture, a solute is a substance dissolved in another substance, known as a solvent. If the attractive forces between the solvent ...

, taking place primarily in the stomach, by the action of the gastric juice

Gastric acid, gastric juice, or stomach acid is a digestive fluid formed within the stomach lining. With a pH between 1 and 3, gastric acid plays a key role in digestion of proteins by activating digestive enzymes, which together break down the ...

.

Reproduction

Spallanzani described animal (mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

) reproduction in his ''Experiencias Para Servir a La Historia de La Generación De Animales y Plantas'' (1786). He was the first to show that fertilisation requires both spermatozoa

A spermatozoon (; also spelled spermatozoön; ; ) is a motile sperm cell, or moving form of the haploid cell that is the male gamete. A spermatozoon joins an ovum to form a zygote. (A zygote is a single cell, with a complete set of chromosomes, ...

and an ovum

The egg cell, or ovum (plural ova), is the female reproductive cell, or gamete, in most anisogamous organisms (organisms that reproduce sexually with a larger, female gamete and a smaller, male one). The term is used when the female gamete is ...

. He was the first to perform in vitro fertilization

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a process of fertilisation where an egg is combined with sperm in vitro ("in glass"). The process involves monitoring and stimulating an individual's ovulatory process, removing an ovum or ova (egg or eggs) ...

, with frogs, and an artificial insemination

Artificial insemination is the deliberate introduction of sperm into a female's cervix or uterine cavity for the purpose of achieving a pregnancy through in vivo fertilization by means other than sexual intercourse. It is a fertility treatme ...

, using a dog. Spallanzani showed that some animals, especially newts

A newt is a salamander in the subfamily Pleurodelinae. The terrestrial juvenile phase is called an eft. Unlike other members of the family Salamandridae, newts are semiaquatic, alternating between aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Not all aqua ...

, can regenerate some parts of their body if injured or surgically removed.

In spite of his scientific background, Spallanzani endorsed preformationism

In the history of biology, preformationism (or preformism) is a formerly popular theory that organisms develop from miniature versions of themselves. Instead of assembly from parts, preformationists believed that the form of living things exist, ...

, an idea that organisms develop from their own miniature selves; e.g. animals from minute animals, animalcules

Animalcule ('little animal', from Latin ''animal'' + the diminutive suffix ''-culum'') is an old term for microscopic organisms that included bacteria, protozoans, and very small animals. The word was invented by 17th-century Dutch scientist A ...

. In 1784, he performed filtration experiment in which he successfully separated seminal fluid of frogs – a liquid portion and a gelatinous animalcule (spermatozoa) portion. But then he assumed that it was the liquid part which could induce fertilisation. A staunch ovist, he believed that animal form was already developed in the eggs and fertilisation by semen was only an activation for growth.

Echolocation

Spallanzani is also famous for extensive experiments in 1793 on how bats could fly at night to detect objects (including prey) and avoid obstacles, where he concluded that bats do not use their eyes for navigation, but some other sense. He was originally inspired by his observation that tamed barn owl flew properly at night under a dim-lit candle, but struck against the wall when the candle was put out. He managed to capture three wild bats in Scandiano, and performed similar experiment, on which he wrote (on 20 August 1793): A few days later he took two bats and covered their eyes with opaque disc made ofbirdlime

Birdlime or bird lime is an adhesive substance used in trapping birds. It is spread on a branch or twig, upon which a bird may land and be caught. Its use is illegal in many jurisdictions.

Manufacture

Historically, the substance has been prepa ...

. To his astonishment, both bats flew completely normally. He went further by surgically removing the eyeballs of one bat, which he observed as:

He concluded that bats do not need vision for navigation; although he failed to find the reason. At the time other scientists were sceptical and ridiculed his findings. A contemporary of Spallanzani, the Swiss physician and naturalist Louis Jurine

Louis Jurine (; 6 February 1751 – 20 October 1819) was a Swiss physician, surgeon and naturalist mainly interested in entomology. He lived in Geneva.

Surgeon

He studied surgery in Paris and quickly acquired a great reputation for his expertis ...

, learned of Spallanzani's experiments, investigated the possible mechanism of bat navigation. He discovered that bat flight was disoriented when their ears were plugged. But Spallanzani did not believe that it was about hearing since bats flew very silently. He repeated his experiments by using improved ear plugs using turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, terebenthene, terebinthine and (colloquially) turps) is a fluid obtained by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. Mainly used as a special ...

, wax, pomatum

Pomade (; French ''pommade'') or pomatum is a greasy, waxy, or water-based substance that is used to style hair. Pomade generally gives the user's hair a shiny and slick appearance. It lasts longer than most hair-care products, and often re ...

or tinder

Tinder is easily combustible material used to start a fire. Tinder is a finely divided, open material which will begin to glow under a shower of sparks. Air is gently wafted over the glowing tinder until it bursts into flame. The flaming tinder i ...

mixed with water, to find that blinded bats could not navigate without hearing. He was still suspicious that deafness alone was the cause of disoriented flight and that hearing was vital that he conducted some rather painful experiments such as burning and removing the external ear, and piercing through the inner ear. After these operations, he became convinced that hearing was fundamental to normal bat flight, upon which he noted:

By then he was too convinced that he suggested the ear was an organ of navigation, writing:

The exact scientific principle was discovered only in 1938 by two American biologists Donald Griffin

Donald Redfield Griffin (August 3, 1915 – November 7, 2003) was an American professor of zoology at various universities who conducted seminal research in animal behavior, animal navigation, acoustic orientation and sensory biophysics. In 1938, ...

and Robert Galambos

Robert Carl Galambos (April 20, 1914 – June 18, 2010) was an American neuroscientist whose pioneering research demonstrated how bats use echolocation for navigation purposes, as well as studies on how sound is processed in the brain.

Biogra ...

.

Fossils

Spallanzani studied the formation and origin of marine fossils found in distant regions of the sea and over the ridge mountains in some regions of Europe, which resulted in the publication in 1755 of a small dissertation, "''Dissertazione sopra i corpi marino-montani then presented at the meeting the Accademia degli Ipocondriaci di Reggio Emilia''". Although aligned to one of the trends of his time, which attributed the occurrence of marine fossils on mountains to the natural movement of the sea, not theuniversal flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these Mythology, myths and the ...

, Spallanzani developed his own hypothesis, based on the dynamics of the forces that changed the state of the Earth after God's creation.

A few years later, Spallanzani published reports about trips he made to Portovenere

Porto Venere (; until 1991 ''Portovenere''; lij, Pòrtivene) is a town and '' comune'' (municipality) located on the Ligurian coast of Italy in the province of La Spezia. It comprises the three villages of Fezzano, Le Grazie and Porto Venere, ...

, Cerigo Island, and Two Sicilies, addressing important issues such as the discovery of fossil shells within volcanic rocks, human fossils, and the existence of fossils of extinct species. His concern with fossils witnesses how, in the style of the eighteenth century, Spallanzani integrated studies of the three kingdoms of nature.

Other works

Spallanzani studied and made important descriptions on blood circulation and respiration. In 1777, he gave the nameTardigrada

Tardigrades (), known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged segmented micro-animals. They were first described by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, who called them Kleiner Wasserbä ...

(from Latin meaning "slow-moving") for the phylum of animal group comprising one of the most durable extremophiles still to this day.

In 1788 he visited Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples

The Gulf of Naples (), also called the Bay of Naples, is a roughly 15-kilometer-wide (9 ...

and the volcanoes of the Lipari Islands

Lipari (; scn, Lìpari) is the largest of the Aeolian Islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, southern Italy; it is also the name of the island's main town and ''comune'', which is administratively part of the Metropolit ...

and Mount Etna in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. He visited the latter along with Carlo Gemmellaro

Carlo Gemmellaro (1787-1866) was an Italian naturalist and geologist. He was noted for his studies on the vulcanology of his native Sicily. His son Gaetano Giorgio Gemmellaro was a noted geologist, paleontologist and politician, who served as ...

. He embodied the results of his researches in a large work (''Viaggi alle due Sicilie ed in alcune parti dell'Appennino''), published four years later.

Much of his collections, which he kept at the end of his life in his house in Scandiano, were purchased by the city of Reggio Emilia

Reggio nell'Emilia ( egl, Rèz; la, Regium Lepidi), usually referred to as Reggio Emilia, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, and known until 1861 as Reggio di Lombardia, is a city in northern Italy, in the Emilia-Romagna region. It has abou ...

in 1799. They are now in display inside the Palazzo dei Musei in two rooms denominated the ''Museo Spallanzani''.

Publications

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Honours

Spallanzani was elected Fellow of theRoyal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. He was member of Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences ( sv, Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien) is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special ...

, and Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities

The Göttingen Academy of Sciences (german: Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen)Note that the German ''Wissenschaft'' has a wider meaning than the English "Science", and includes Social sciences and Humanities. is the second oldest of the se ...

.

References

Bibliography

General

*Paul de Kruif Paul Henry de Kruif (, rhyming with "life") (1890–1971) was an American microbiologist and author of Dutch descent. Publishing as Paul de Kruif, he is most noted for his 1926 book, ''Microbe Hunters''. This book was not only a bestseller for a le ...

, ''Microbe Hunters'' (2002 reprint) ;

*Nordenskiöld, E. P. 1935 pallanzani, L.''Hist. of Biol''. 247–248

*Rostand, J. 1997, ''Lazzaro Spallanzani e le origini della biologia sperimentale'', Torino, Einaudi.

*

Work on insects

* *Gibelli, V. 1971 ''L. Spallanzani''. Pavia. *Lhoste, J. 1987 ''Les entomologistes français. 1750–1950''. INRA (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique), Paris. *Osborn, H. 1946 ''Fragments of Entomological History Including Some Personal Recollections of Men and Events''. Columbus, Ohio, Published by the Author. *Osborn, H. 1952 ''A Brief History of Entomology Including Time of Demosthenes and Aristotle to Modern Times with over Five Hundred Portraits''.Columbus, Ohio, The Spahr & Glenn Company.See also

*List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby union ...

*Charles Jurine

Charles Jurine (1751–1819) was a Swiss zoologist who, inspired by a letter by Lazzaro Spallanzani to the Geneva Natural History Society, set about showing that bats used their ears to navigate. He corresponded with Spallanzani, who confirmed his ...

External links

Page describing, with pictures, some of Lazzaro Spallanzani's memories

Göttingen State and University Library

The Göttingen State and University Library (german: Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen or SUB Göttingen) is the library for Göttingen University as well as for the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and is the state li ...

Digitised ''Viaggi alle due Sicilie e in alcune parti dell'Appennino''Guide to the Lazzaro Spallanzani Papers 1768-1793

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Spallanzani, Lazzaro 1729 births 1799 deaths People from Scandiano 18th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Catholic clergy scientists Italian biologists Italian entomologists Deaths from cancer in Lombardy Deaths from bladder cancer Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Italian physiologists