Solid South on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the

At the start of the

At the start of the  Even after white Democrats regained control of state legislatures, some black candidates were elected to local offices and state legislatures in the South. Black U.S. Representatives were elected from the South as late as the 1890s, usually from overwhelmingly black areas. Also in the 1890s, the

Even after white Democrats regained control of state legislatures, some black candidates were elected to local offices and state legislatures in the South. Black U.S. Representatives were elected from the South as late as the 1890s, usually from overwhelmingly black areas. Also in the 1890s, the

/ref> These devices applied to all citizens; in practice they disfranchised most black citizens and also "would remove rom voter registration rollsthe less educated, less organized, more impoverished whites as well – and that would ensure one-party Democratic rules through most of the 20th century in the South".Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon"

''Constitutional Commentary'', Vol.17, 2000, p.10, Accessed 10 Mar 2008Glenn Feldman, ''The Disenfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama'', Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136 All the Southern states adopted provisions that restricted voter registration and suffrage, including new requirements for

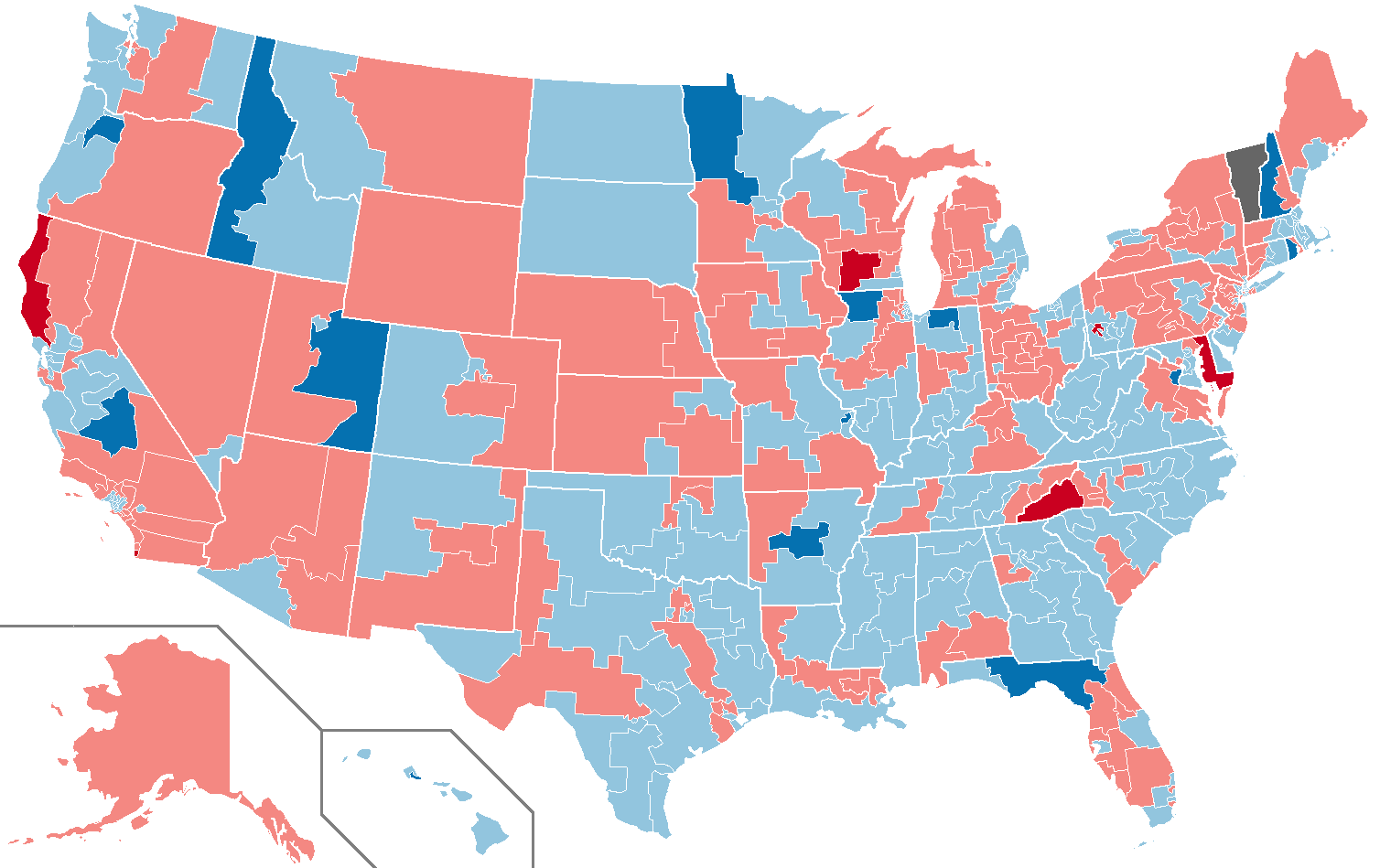

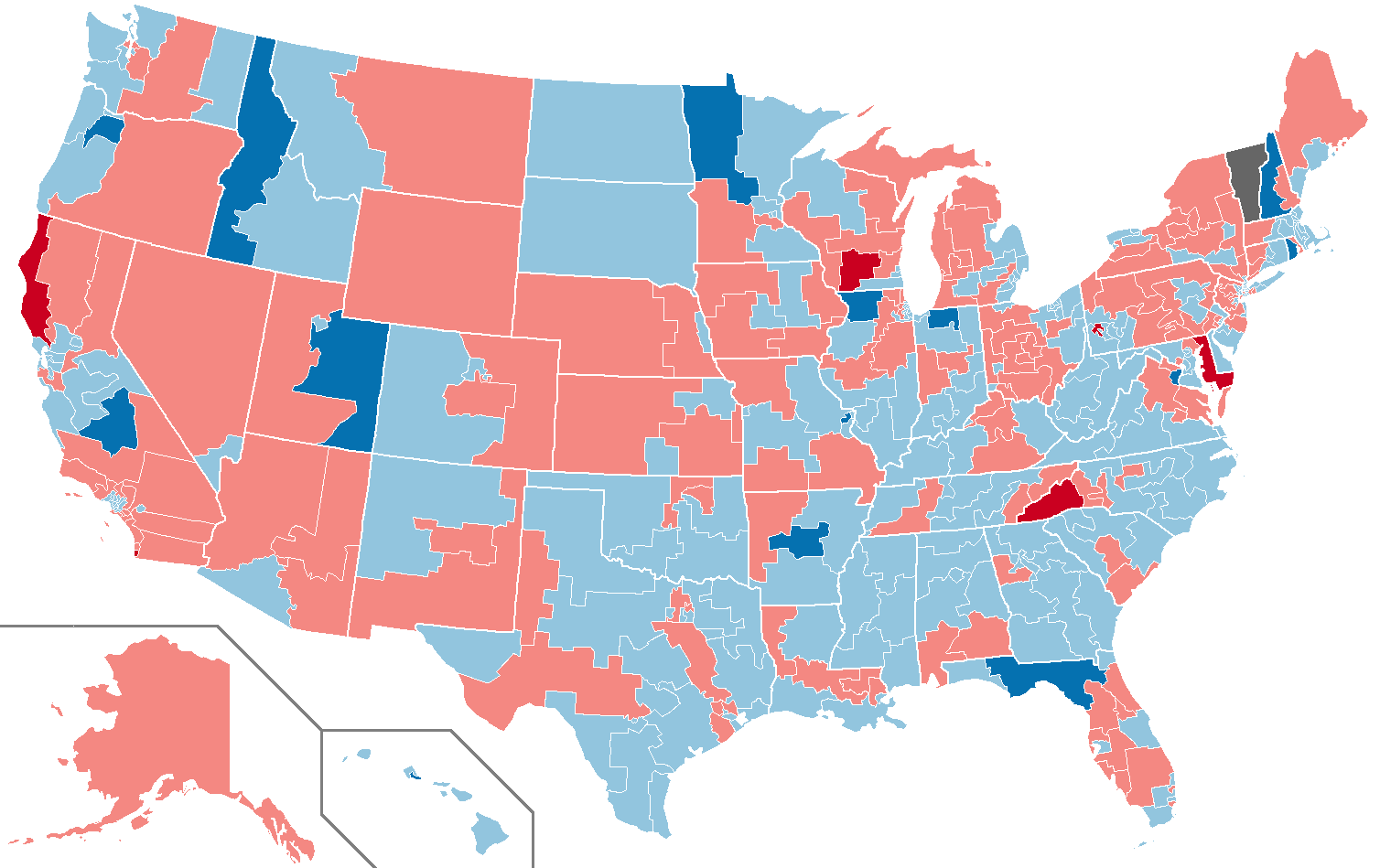

‘How the Red and Blue Map Evolved Over the Past Century’

''America Magazine'' in ''The National Catholic Review''; June 29, 2016 In the

The 1896 election resulted in the first break in the Solid South. Florida politician Marion L. Dawson, writing in the ''

The 1896 election resulted in the first break in the Solid South. Florida politician Marion L. Dawson, writing in the ''

In the 1968 election,

In the 1968 election,  In the 1992 election and 1996, when the Democratic ticket consisted of two Southerners, (

In the 1992 election and 1996, when the Democratic ticket consisted of two Southerners, (

''Why the Solid South? Or, Reconstruction and Its Results.''

Baltimore, MD: R. H. Woodward & Co. * Sabato, Larry (1977). ''The Democratic Party Primary in Virginia: Tantamount to Election No Longer.'' Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia. Electoral geography of the United States History of the Southern United States United States presidential elections terminology Politics of the Southern United States Democratic Party (United States) Politics of the United States White supremacy in the United States Political history of the United States

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especially between the end of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

in 1877 and the passage of the Civil Rights Act

Civil Rights Act may refer to several acts of the United States Congress, including:

* Civil Rights Act of 1866, extending the rights of emancipated slaves by stating that any person born in the United States regardless of race is an American ci ...

in 1964. During this period, the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

overwhelmingly controlled southern state legislatures, and most local, state and federal officeholders in the South were Democrats. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats wi ...

disenfranchised blacks in all Southern states, along with a few non-Southern states doing the same as well. This resulted essentially in a one-party system

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

, in which a candidate's victory in Democratic primary election

Primary elections, or direct primary are a voting process by which voters can indicate their preference for their party's candidate, or a candidate in general, in an upcoming general election, local election, or by-election. Depending on the ...

s was tantamount to election

A safe seat is an electoral district (constituency) in a legislative body (e.g. Congress, Parliament, City Council) which is regarded as fully secure, for either a certain political party, or the incumbent representative personally or a combinati ...

to the office itself. White primaries

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South ...

were another means that the Democrats used to consolidate their political power, excluding blacks from voting in primaries.

The "Solid South" is a loose term referring to the states that made up the voting bloc at any point in time. The Southern region as defined by U.S. Census comprises sixteen states plus Washington, D.C.—Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

, and Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

. The idea of the Solid South shifted over time and did not always necessarily correspond to the census definition. After Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, all the former slave states were dominated by the Democratic Party for at least two decades. Delaware, the least secessionist slave state, was considered a reliable state for the Democratic Party, as was Missouri, classified as a Midwestern state by the U.S. Census. From the early part of the 20th century on, Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and West Virginia ceased to be reliably Democratic (although West Virginia once again became a reliably Democratic state with the New Deal era).

History

At the start of the

At the start of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, there were 34 states in the United States, 15 of which were slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

s. Slavery was also legal in the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

. Eleven of these slave states seceded from the United States to form the Confederacy: South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, and North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

. The slave states that stayed in the Union were Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

, and Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, and they were referred to as the border states. In 1861, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

was created out of Virginia, and admitted in 1863 and considered a border state. By the time the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

was made in 1863, Tennessee was already under Union control. Accordingly, the Proclamation applied only to the 10 remaining Confederate states. Several of the border states abolished slavery before the end of the Civil War—Maryland in 1864, Missouri in 1865, one of the Confederate states, Tennessee in 1865, West Virginia in 1865, and the District of Columbia in 1862. However, slavery persisted in Delaware, Kentucky, and 10 of the 11 former Confederate states, until the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representative ...

abolished slavery throughout the United States on December 18, 1865.

Democratic dominance of the South originated in the struggle of white Southerners during and after Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

(1865–1877) to reestablish white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

and disenfranchise black people. The U.S. government under the Republican Party had defeated the Confederacy, abolished slavery, and enfranchised black people. In several states, black voters were a majority or close to it. Republicans supported by black people controlled state governments in these states. Thus the Democratic Party became the vehicle for the white supremacist "Redeemers". The Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, as well as other insurgent paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

groups such as the White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing. Its f ...

and Red Shirts from 1874, acted as "the military arm of the Democratic party" to disrupt Republican organizing, and intimidate and suppress black voters.

By 1876, " Redeemer" Democrats had taken control of all state governments in the South. From then until the 1960s, state and local government in the South was almost entirely monopolized by Democrats. The Democrats elected all but a handful of U.S. Representatives and Senators, and Democratic presidential candidates regularly swept the region – from 1880 through 1944, winning a cumulative total of 182 of 187 states. The Democrats reinforced the loyalty of white voters by emphasizing the suffering of the South during the war at the hands of "Yankee invaders" under Republican leadership, and the noble service of their white forefathers in " the Lost Cause". This rhetoric was effective with many Southerners. However, this propaganda was totally ineffective in areas that had been loyal to the Union during the war, such as eastern Tennessee. Most of East Tennessee welcomed U.S. troops as liberators, and voted Republican even in the Solid South period.

Even after white Democrats regained control of state legislatures, some black candidates were elected to local offices and state legislatures in the South. Black U.S. Representatives were elected from the South as late as the 1890s, usually from overwhelmingly black areas. Also in the 1890s, the

Even after white Democrats regained control of state legislatures, some black candidates were elected to local offices and state legislatures in the South. Black U.S. Representatives were elected from the South as late as the 1890s, usually from overwhelmingly black areas. Also in the 1890s, the Populists

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

developed a following in the South, among poor white

Poor White is a sociocultural classification used to describe economically disadvantaged Whites in the English-speaking world, especially White Americans with low incomes.

In the United States, Poor White (or Poor Whites of the South for ...

people who resented the Democratic Party establishment. Populists formed alliances with Republicans (including black Republicans) and challenged the Democratic bosses, even defeating them in some cases.

To prevent such coalitions in the future and to end the violence associated with suppressing the black vote during elections, Southern Democrats acted to disfranchise both black people and poor white people. From 1890 to 1910, beginning with Mississippi, Southern states adopted new constitutions and other laws including various devices to restrict voter registration, disfranchising virtually all black and many poor white residents.Richard M. Valelly, ''The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement'' University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 146–147/ref> These devices applied to all citizens; in practice they disfranchised most black citizens and also "would remove rom voter registration rollsthe less educated, less organized, more impoverished whites as well – and that would ensure one-party Democratic rules through most of the 20th century in the South".Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon"

''Constitutional Commentary'', Vol.17, 2000, p.10, Accessed 10 Mar 2008Glenn Feldman, ''The Disenfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama'', Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136 All the Southern states adopted provisions that restricted voter registration and suffrage, including new requirements for

poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

, longer residency, and subjective literacy tests. Some also used the device of grandfather clause

A grandfather clause, also known as grandfather policy, grandfathering, or grandfathered in, is a provision in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations while a new rule will apply to all future cases. Those exempt from t ...

s, exempting voters who had a grandfather voting by a particular year (usually before the Civil War, when black people could not vote.)Michael Perman.''Struggle for Mastery: Disenfranchisement (sic) in the South, 1888–1908'' (2001), Introduction

White Democrats also opposed Republican economic policies such as the high tariff and the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

, both of which were seen as benefiting Northern industrial interests at the expense of the agrarian South in the 19th century. Nevertheless, holding all political power was at the heart of their resistance. From 1876 through 1944, the national Democratic party opposed any calls for civil rights for black people. In Congress Southern Democrats blocked such efforts whenever Republicans targeted the issue.

White Democrats passed "Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

" laws which reinforced white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

through racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

. The Fourteenth Amendment provided for apportionment of representation in Congress to be reduced if a state disenfranchised part of its population. However, this clause was never applied to Southern states that disenfranchised black residents. No black candidate was elected to any office in the South for decades after the turn of the century; and they were also excluded from juries and other participation in civil life.

Democratic candidates won by large margins in a majority of Southern states in every presidential election from 1876

Events

January–March

* January 1

** The Reichsbank opens in Berlin.

** The Bass Brewery Red Triangle becomes the world's first registered trademark symbol.

* February 2 – The National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs i ...

to 1948, except for 1928, when the Democratic candidate was Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a C ...

, a Catholic New Yorker; and even in that election, the divided South provided Smith with nearly three-fourths of his electoral votes. Scholar Richard Valelly credited Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's 1912 election to the disfranchisement of black people in the South, and also noted far-reaching effects in Congress, where the Democratic South gained "about 25 extra seats in Congress for each decade between 1903 and 1953".

In the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

(South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana), Democratic dominance was overwhelming, with Democrats routinely receiving 80%–90% of the vote, and only a tiny number of Republicans holding state legislative seats or local offices. Mississippi and South Carolina were the most extreme cases – between 1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15), 2 ...

and 1944

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 2 – WWII:

** Free French General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny is appointed to command French Army B, part of the Sixth United States Army Group in Nor ...

, only in 1928, when the three subcoastal Mississippi counties of Pearl River

The Pearl River, also known by its Chinese name Zhujiang or Zhu Jiang in Mandarin pinyin or Chu Kiang and formerly often known as the , is an extensive river system in southern China. The name "Pearl River" is also often used as a catch-a ...

, Stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

and George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

went for Hoover, did the Democrats lose even one of these two states' counties in any presidential election. In the remaining states, the German-American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

Texas counties of Gillespie and Kendall, and a number of counties in Appalachia

Appalachia () is a cultural region in the Eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York State to northern Alabama and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ca ...

n parts of Alabama and Georgia, would vote Republican in presidential elections through this period.Sullivan, Robert David‘How the Red and Blue Map Evolved Over the Past Century’

''America Magazine'' in ''The National Catholic Review''; June 29, 2016 In the

Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

(Tennessee, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Virginia), Republicans retained a significant presence mainly in these remote Appalachian and Ozark regions which supported the Union during the Civil War, even winning occasional governorships and often drawing over 40% in presidential votes.

By the 1920s, as memories of the Civil War faded, the Solid South cracked slightly. For instance, a Republican was elected U.S. Representative from Texas in 1920, serving until 1932. The Republican national landslides in 1920 and 1928 had some effects. In the 1920 elections, Tennessee elected a Republican governor and five out of 10 Republican U.S. Representatives, and became the first former Confederate state to vote for a Republican candidate for U.S. President since Reconstruction. However, with the Democratic national landslide of 1932, the South again became solidly Democratic.

In the 1930s, black voters outside the South largely switched to the Democrats, and other groups with an interest in civil rights (notably Jews, Catholics, and academic intellectuals) became more powerful in the party. This led to the national Democrats adopting a civil rights plank in 1948. In response, a faction of Deep South Democrats ran their own segregationist " Dixiecrat" presidential ticket, which carried four states: South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Even before then, a number of conservative Southern Democrats felt chagrin at the national party's growing friendliness to organized labor during the Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

administration, and began splitting their tickets as early as the 1930s.

Southern demography also began to change. From 1910 through 1970, about 6.5 million black Southerners moved to urban areas in other parts of the country in the Great Migration, and demographics began to change Southern states in other ways. Florida began to expand rapidly, with retirees and other migrants from other regions becoming a majority of the population. Many of these new residents brought their Republican voting habits with them, diluting traditional Southern hostility to the Republicans. The Republican Party began to make gains in the South, building on other cultural conflicts as well. By the mid-1960s, changes had come in many of the southern states. Former Dixiecrat Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina changed parties in 1964; Texas elected a Republican Senator in 1961; Florida and Arkansas elected Republican governors in 1966. In the Upper South, where Republicans had always been a small presence, Republicans gained a few seats in the House and Senate.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the South was still overwhelmingly Democratic at the state level, with majorities in all state legislatures and most U.S. House delegations. Over the next thirty years, this gradually changed. Veteran Democratic officeholders retired or died, and older voters who were still rigidly Democratic also died off. There were also increasing numbers of migrants from other areas, especially in Florida, Texas, Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina. As part of the Republican Revolution in the 1994 elections, Republicans captured a majority of the U.S. House's southern seats for the first time. As of 2021, they account for a majority of each Southern state's House delegation apart from Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware.

Following the 2016 elections, when Republicans won the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form ...

, every state legislative chamber in the South had a Republican majority for the first time ever. This would remain the case until Democrats regained both Houses of the Virginia Legislature

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 1619 ...

in 2019.

Today, the South is considered a Republican stronghold at the state and federal levels. Some political experts identify a re- Southernization of politics and culture in the Clinton presidency coinciding with House and Senate leading positions held by southerners.

West Virginia

ForWest Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, "reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, in a sense, began in 1861". Unlike the other border states, West Virginia did not send the majority of its soldiers to the Union. The prospect of those returning ex-Confederates prompted the Wheeling state government to implement laws that restricted their right of suffrage, practicing law and teaching, access to the legal system, and subjected them to "war trespass" lawsuits. The lifting of these restrictions in 1871 resulted in the election of John J. Jacob, a Democrat, to the governorship. It also led to the rejection of the war-time constitution by public vote and a new constitution written under the leadership of ex-Confederates such as Samuel Price

Samuel Price (July 28, 1805February 25, 1884) was Virginia lawyer and politician, who helped to establish the state of West Virginia during the American Civil War and became Lieutenant Governor, and later a United States senator.

Early and fami ...

, Allen T. Caperton and Charles James Faulkner

Charles James Faulkner (September 21, 1847January 13, 1929) was a United States senator from West Virginia.

Early life

Born on the family estate, "Boydville," near Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia). His father was Charles James Faulk ...

. In 1876 the state Democratic ticket of eight candidates were all elected, seven of whom were Confederate veterans. For nearly a generation West Virginia was part of the Solid South.

However, Republicans returned to power in 1896, controlling the governorship for eight of the next nine terms, and electing 82 of 106 U.S. Representatives. In 1932, as the nation swung to the Democrats, West Virginia became solidly Democratic. It was perhaps the most reliably Democratic state in the nation between 1932 and 1996, being one of just two states (along with Minnesota) to vote for a Republican president as few as three times in that interval. Moreover, unlike Minnesota (or other nearly as reliably Democratic states like Massachusetts and Rhode Island), it usually had a unanimous (or nearly unanimous) congressional delegation

A parliamentary delegation (or congressional delegation, also CODEL or codel, in the United States) is an official visit abroad by a member or members of a legislature.

To schedule a parliamentary delegation, a member must apply to the relevant c ...

and only elected two Republicans as Governor (albeit for a combined 20 years between them). West Virginian voters shifted toward the Republican Party from 2000 onward, as the Democratic Party became more strongly identified with environmental policies

Environmental policy is the commitment of an organization or government to the laws, regulations, and other policy mechanisms concerning environmental issues. These issues generally include air and water pollution, waste management, ecosystem mana ...

anathema to the state's coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

industry and with socially liberal policies, and it can now be called a solidly red state.

Presidential voting

The 1896 election resulted in the first break in the Solid South. Florida politician Marion L. Dawson, writing in the ''

The 1896 election resulted in the first break in the Solid South. Florida politician Marion L. Dawson, writing in the ''North American Review

The ''North American Review'' (NAR) was the first literary magazine in the United States. It was founded in Boston in 1815 by journalist Nathan Hale and others. It was published continuously until 1940, after which it was inactive until revived a ...

'', observed: "The victorious party not only held in line those States which are usually relied upon to give Republican majorities ... More significant still, it invaded the Solid South, and bore off West Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky; caused North Carolina to tremble in the balance and reduced Democratic majorities in the following States: Alabama, 39,000; Arkansas, 29,000; Florida, 6,000; Georgia, 49,000; Louisiana, 33,000; South Carolina, 6,000; and Texas, 29,000. These facts, taken together with the great landslide of 1894 and 1895, which swept Missouri and Tennessee, Maryland and Kentucky over into the country of the enemy, have caused Southern statesmen to seriously consider whether the so-called Solid South is not now a thing of past history".

In the 1904 election, Missouri supported Republican Theodore Roosevelt, while Maryland awarded its electors to Democrat Alton Parker, despite Roosevelt's winning by 51 votes.

By the 1916 election, disfranchisement of blacks and many poor whites was complete, and voter rolls had dropped dramatically in the South. Closing out Republican supporters gave a bump to Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, who took all the electors across the South (apart from Delaware and West Virginia), as the Republican Party was stifled without support by African Americans.

The 1920 election was a referendum on President Wilson's League of Nations. Pro-isolation sentiment in the South benefited Republican Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

, who won Tennessee, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Maryland. In 1924, Republican Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

won Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland; and in 1928, Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

, perhaps benefiting from bias against his Democratic opponent Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a C ...

(who was a Roman Catholic and opposed Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

), won not only those Southern states that had been carried by either Harding or Coolidge (Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Maryland), but also won Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Virginia, none of which had voted Republican since Reconstruction. He furthermore came within 2.5% of carrying the Deep South state of Alabama. (All of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover carried the two Southern states that had supported Hughes in 1916, West Virginia and Delaware.)

Al Smith had received serious backlash as a Catholic in the largely Protestant South in 1928, losing several states in the Outer South, only managing to hold Arkansas outside the Deep South. Smith had also nearly lost Alabama, which he held by 3%, which had Hoover won, would have physically split the Solid South.

The South appeared "solid" again during the period of Roosevelt's political dominance, as his welfare programs and military buildup invested considerable money in the South, benefiting many of its citizens, including during the Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) an ...

.

Democratic President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

's support of the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

, combined with the adoption of a civil rights plank in the 1948 Democratic platform, prompted many Southerners to walk out of the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

and form the Dixiecrat Party. This splinter party played a significant role in the 1948 election; the Dixiecrat candidate, Strom Thurmond, carried Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, and his native South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

.

In the elections of 1952 and 1956, the popular Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, commander of the Allied armed forces during World War II, carried several Southern states, with especially strong showings in the new suburbs. Most of the Southern states he carried had voted for at least one of the Republican winners in the 1920s, but in 1956, Eisenhower carried Louisiana, becoming the first Republican to win the state since Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

in 1876

Events

January–March

* January 1

** The Reichsbank opens in Berlin.

** The Bass Brewery Red Triangle becomes the world's first registered trademark symbol.

* February 2 – The National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs i ...

. The rest of the Deep South voted for his Democratic opponent, Adlai Stevenson.

In the 1960 election, the Democratic nominee, John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, continued his party's tradition of selecting a Southerner as the vice presidential candidate (in this case, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

of Texas). Kennedy and Johnson, however, both supported civil rights. In October 1960, when Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

was arrested at a peaceful sit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

in Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, Kennedy placed a sympathetic phone call to King's wife, Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King ( Scott; April 27, 1927 – January 30, 2006) was an American author, activist, and civil rights leader who was married to Martin Luther King Jr. from 1953 until his death. As an advocate for African-American equality, she w ...

, and Kennedy's brother Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

helped secure King's release. King expressed his appreciation for these calls. Although King made no endorsement, his father, who had previously endorsed Republican Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, switched his support to Kennedy.

Because of these and other events, the Democrats lost ground with white voters in the South, as those same voters increasingly lost control over what was once a whites-only Democratic Party in much of the South. The 1960 election was the first in which a Republican presidential candidate received electoral votes from the former Confederacy while losing nationally. Nixon carried Virginia, Tennessee, and Florida. Though the Democrats also won Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, slates of unpledged elector

In United States presidential elections, an unpledged elector is a person nominated to stand as an elector but who has not pledged to support any particular presidential or vice presidential candidate, and is free to vote for any candidate when el ...

s, representing Democratic segregationists, awarded those states' electoral votes to Harry Byrd, rather than Kennedy.

The parties' positions on civil rights continued to evolve in the run up to the 1964 election. The Democratic candidate, Johnson, who had become president after Kennedy's assassination, spared no effort to win passage of a strong Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. After signing the landmark legislation, Johnson said to his aide, Bill Moyers

Bill Moyers (born Billy Don Moyers, June 5, 1934) is an American journalist and political commentator. Under the Johnson administration he served from 1965 to 1967 as the eleventh White House Press Secretary. He was a director of the Counci ...

: "I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come." In contrast, Johnson's Republican opponent, Senator Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for presiden ...

of Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

, voted against the Civil Rights Act, believing it enhanced the federal government and infringed on the private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

rights of businessmen. Goldwater did support civil rights in general and universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

, and voted for the 1957 Civil Rights Act (though casting no vote on the 1960 Civil Rights Act), as well as voting for the 24th Amendment, which banned poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

as a requirement for voting. This was one of the devices that states used to disfranchise African Americans and the poor.

That November, Johnson won a landslide electoral victory, and the Republicans suffered significant losses in Congress. Goldwater, however, besides carrying his home state of Arizona, carried the Deep South: voters in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina had switched parties for the first time since Reconstruction. Goldwater notably won only in Southern states that had voted against Republican Richard Nixon in 1960, while not winning a single Southern state which Nixon had carried. Previous Republican inroads in the South had been concentrated on high-growth suburban areas, often with many transplants, as well as on the periphery of the South.

According to a quantitative analysis for the National Bureau of Economic Research

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is an American private nonprofit research organization "committed to undertaking and disseminating unbiased economic research among public policymakers, business professionals, and the academic c ...

, racism played a central role in the decline in relative white Southern Democratic identification.

"Southern strategy": end of Solid South

In the 1968 election,

In the 1968 election, Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

saw the cracks in the Solid South as an opportunity to tap into a group of voters who had historically been beyond the reach of the Republican Party. With the aid of Harry Dent and South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had switched to the Republican Party in 1964, Nixon ran his 1968 campaign on states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

and "law and order". As a key component of this strategy, he selected as his running mate Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second vice president to resign the position, the other being John ...

. Liberal Northern Democrats accused Nixon of pandering to Southern whites, especially with regard to his "states' rights" and "law and order" positions, which were widely understood by black leaders to legitimize the status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, political, religious or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the current state of social structure and/or values. W ...

of Southern states' discrimination. This tactic was described in 2007 by David Greenberg in ''Slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

'' as "dog-whistle politics

In politics, a dog whistle is the use of coded or suggestive language in political messaging to garner support from a particular group without provoking opposition. The concept is named after ultrasonic dog whistles, which are audible to dogs bu ...

". According to an article in ''The American Conservative'', Nixon adviser and speechwriter Pat Buchanan disputed this characterization.

The independent candidacy of George Wallace, former Democratic governor of Alabama, partially negated Nixon's Southern Strategy. With a much more explicit attack on integration and black civil rights, Wallace won all but two of Goldwater's states (the exceptions being South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

) as well as Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

and one of North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

's electoral votes. Nixon picked up Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

. The Democrat, Hubert Humphrey, won Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, heavily unionized West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, and heavily urbanized Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. Writer Jeffrey Hart

Jeffrey Peter Hart (February 23, 1930 – February 16, 2019) was an American cultural critic, essayist, columnist, and Professor Emeritus of English at Dartmouth College.

Life and career

Hart was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. Aft ...

, who worked on the Nixon campaign as a speechwriter

A speechwriter is a person who is hired to prepare and write speeches that will be delivered by another person. Speechwriters are employed by many senior-level elected officials and executives in the government and private sectors. They can also be ...

, said in 2006 that Nixon did not have a "Southern Strategy", but "Border State Strategy" as he said that the 1968 campaign ceded the Deep South to George Wallace. Hart suggested that the press called it a "Southern Strategy" as they are "very lazy".

The 1968 election had been the first election in which both the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

and Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

bolted from the Democratic party simultaneously. The Upper South had backed Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956, as well as Nixon in 1960. The Deep South had backed Goldwater just four years prior. Despite the two regions of the South still backing different candidates, Wallace in the Deep South and Nixon in the Upper South, only Texas, Maryland, and West Virginia had held up against the majority Nixon-Wallace vote for Humphrey. By 1972, Nixon had swept the South altogether, Outer and Deep South alike, marking the first time in American history a Republican won every Southern state.

At the 1976 election, Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

, a Southern governor, gave Democrats a short-lived comeback in the South, winning every state in the old Confederacy except for Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, which was narrowly lost. However, in his unsuccessful 1980 re-election bid, the only Southern states he won were his native state of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. The year 1976 was the last year a Democratic presidential candidate won a majority of Southern electoral votes. The Republicans took all the region's electoral votes in the 1984 election and every state except West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

in 1988

File:1988 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The oil platform Piper Alpha explodes and collapses in the North Sea, killing 165 workers; The USS Vincennes (CG-49) mistakenly shoots down Iran Air Flight 655; Australia celebrates its Australian ...

.

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

and Al Gore

Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (born March 31, 1948) is an American politician, businessman, and environmentalist who served as the 45th vice president of the United States from 1993 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton. Gore was the Democratic Part ...

), the Democrats and Republicans split the region. In both elections, Clinton won Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

, while the Republican won Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, and Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

. Bill Clinton won Georgia in 1992, but lost it in 1996 to Bob Dole. Conversely, Clinton lost Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

in 1992 to George Bush, but won it in 1996.

In 2000

File:2000 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Protests against Bush v. Gore after the 2000 United States presidential election; Heads of state meet for the Millennium Summit; The International Space Station in its infant form as seen from ...

, however, Gore received no electoral votes from the South, even from his home state of Tennessee, apart from heavily urbanized and uncontested Maryland and Delaware. The popular vote in Florida was extraordinarily close in awarding the state's electoral votes to George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

. This pattern continued in the 2004 election; the Democratic ticket of John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician and diplomat who currently serves as the first United States special presidential envoy for climate. A member of the Forbes family and the Democratic Party (Unite ...

and John Edwards

Johnny Reid Edwards (born June 10, 1953) is an American lawyer and former politician who served as a U.S. senator from North Carolina. He was the Democratic nominee for vice president in 2004 alongside John Kerry, losing to incumbents George ...

received no electoral votes from the South apart from Maryland and Delaware, even though Edwards was from North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, and was born in South Carolina. However, in the 2008 election, as many areas in the South became more urbanized, liberal, and demographically diverse, Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

won the former Republican strongholds of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

as well as Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

; Obama won Virginia and Florida again in 2012

File:2012 Events Collage V3.png, From left, clockwise: The passenger cruise ship Costa Concordia lies capsized after the Costa Concordia disaster; Damage to Casino Pier in Seaside Heights, New Jersey as a result of Hurricane Sandy; People gather ...

and lost North Carolina by only 2.04 percent. In 2016

File:2016 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: Bombed-out buildings in Ankara following the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt; the impeachment trial of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff; Damaged houses during the 2016 Nagorno-Karabakh ...

, Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

won only Virginia while narrowly losing Florida and North Carolina. And in 2020

2020 was heavily defined by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to global Social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, social and Economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic disruption, mass cancellations and postponements of events, COVID- ...

, Joe Biden won Virginia, a growing stronghold for Democrats, narrowly won Georgia, in large part due to the rapidly growing Atlanta metropolitan area, while narrowly losing Florida and North Carolina.

While the South was shifting from the Democrats to the Republicans, the Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...