siege of Khartoum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Siege of Khartoum (also known as the Battle of Khartoum or Fall of Khartoum) occurred from 13 March 1884 to 26 January 1885. Sudanese Mahdist forces captured the city of

The defeat brought the Mahdi Revolt to the attention of the British government and public. The British

The defeat brought the Mahdi Revolt to the attention of the British government and public. The British

Despite this, Gordon was commanded to evacuate Sudan, which he agreed to do. He was given funds of Pound sterling, £100,000 in credit and was promised "all support and cooperation in their power" by the British and Egyptian authorities. On his way to Khartoum with his assistant, Colonel John Stewart, Gordon stopped in the town of

Gordon's plight excited great concern in the

Gordon's plight excited great concern in the

Accounts differ as to how Gordon was killed. According to one version, when Mahdist warriors broke into the governor's palace, Gordon came outside in full uniform and disdained to fight; he was then killed with a spear, despite orders from the Mahdi to capture Gordon alive. In another version, Gordon was recognised by Mahdists while attempting to reach the neutral Austrian consulate in the city, who shot him dead in the street.

The most detailed account of his death was given by his servant Khaleel Aga Orphali, when debriefed by the British in 1898 (13 years later). According to Orphali, Gordon died fighting on the stairs leading from the first to the ground floor of the west wing of the palace. Gordon was seriously wounded by a spear that hit him in the left shoulder, but continued fighting with Orphali beside him. Orphali stated that:

Accounts differ as to how Gordon was killed. According to one version, when Mahdist warriors broke into the governor's palace, Gordon came outside in full uniform and disdained to fight; he was then killed with a spear, despite orders from the Mahdi to capture Gordon alive. In another version, Gordon was recognised by Mahdists while attempting to reach the neutral Austrian consulate in the city, who shot him dead in the street.

The most detailed account of his death was given by his servant Khaleel Aga Orphali, when debriefed by the British in 1898 (13 years later). According to Orphali, Gordon died fighting on the stairs leading from the first to the ground floor of the west wing of the palace. Gordon was seriously wounded by a spear that hit him in the left shoulder, but continued fighting with Orphali beside him. Orphali stated that:

Project Gutenberg

*

online

online

*Buchan, John. ''Gordon at Khartoum'' (1934)

online

Internet Archive *Chenevix Trench, Charles. ''The Road to Khartoum: a life of General Charles Gordon'' (1979

online free to borrow

*Elton, Godfrey Elton Baron. ''Gordon of Khartoum: The Life of General Charles Gordon'' (Knopf, 1954). *Nicoll, Fergus. ''The Sword of the Prophet: the Mahdi of Sudan and the Death of General Gordon'' (Sutton Publishing, 2004). *Miller, Brook. "Our Abdiel: The British Press and the Lionization of 'Chinese' Gordon." ''Nineteenth-Century Prose'' 32.2 (2005): 127

online

*Snook, Colonel Mike. ''Beyond the Reach of Empire: Wolseley's Failed Campaign to save Gordon and Khartoum'' (Frontline Books, 2013). {{Authority control 1884 in Sudan 1885 in Sudan Conflicts in 1884 Conflicts in 1885

Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

from its Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

garrison, thereby gaining control over the whole of Sudan.

Egypt had controlled Sudan since 1820, but had itself come under British domination in 1882. In 1881, the Mahdist Revolt

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

began in Sudan, led by Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad ( ar, محمد أحمد ابن عبد الله; 12 August 1844 – 22 June 1885) was a Nubian Sufi religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, as a youth, studied Sunni Islam. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi, an ...

who claimed to be the Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a Messianism, messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a de ...

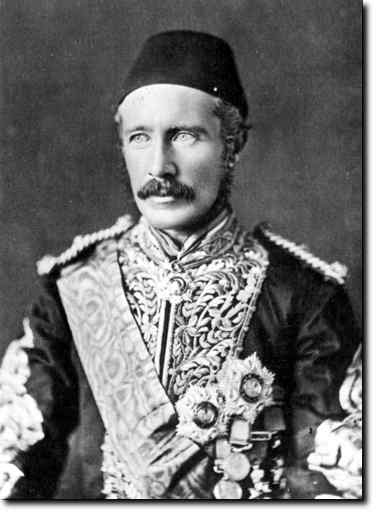

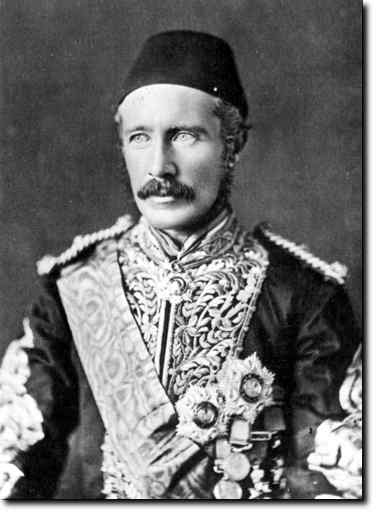

. The Egyptian army was unable to suppress the revolt, being defeated in several battles and retreating to their garrisons. The British refused to send a military force to the area, instead appointing Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in ...

as Governor-General of Sudan, with orders to evacuate Khartoum and the other garrisons. Gordon arrived in Khartoum in February 1884, where he found it impossible to reach the other garrisons which were already besieged. Rather than evacuating immediately, Gordon began to fortify the city, which was cut off when the local tribes switched their support to the Mahdi. Approximately 7,000 Egyptian troops and 27,000 (mostly Sudanese) civilians were besieged in Khartoum by 30,000 Mahdist warriors, rising to 50,000 by the end of the siege.

Attempts by the defenders to break out of the city failed. Food supplies began to run out; they had been expected to last six months, but the siege went on for ten, so the garrison and civilian population began to starve. After months of public pressure, the British government reluctantly agreed to send troops to relieve the siege. With the relief column approaching, the Mahdists launched a night assault on Khartoum. They broke through the defences and killed the entire garrison, including Gordon. A further 4,000 male civilians were killed, while many women and children were enslaved. The relief expedition arrived two days later; realising they were too late, they withdrew from Sudan. The Mahdi then founded a religious state in Sudan, the Mahdiyah which would last for fourteen years.

Background

Strategic situation

TheKhedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which br ...

was nominally a vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back to ...

of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, but came under British military occupation during the 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War

The British conquest of Egypt (1882), also known as Anglo-Egyptian War (), occurred in 1882 between Egyptian and Sudanese forces under Ahmed ‘Urabi and the United Kingdom. It ended a nationalist uprising against the Khedive Tewfik Pasha. It ...

, making it a ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' British protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

. Egypt was mostly left to govern itself under the Khedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Kh ...

, including in its possession of Sudan, which the British regarded as a domestic Egyptian matter.

A revolt had begun in Sudan in 1881, when Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad ( ar, محمد أحمد ابن عبد الله; 12 August 1844 – 22 June 1885) was a Nubian Sufi religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, as a youth, studied Sunni Islam. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi, an ...

claimed to be the mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a Messianism, messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a de ...

– the redeemer of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

prophesied in the hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

scriptures. This Mahdist revolt

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

was supported by many in Sudan, both for religious reasons and due to a desire for independence from Egypt.

The Egyptian Army attempted to suppress the revolt, but were defeated by the Mahdists in November 1883 at the Battle of El Obeid

The Battle of Shaykan was fought between Anglo-Egyptian forces under the command of Hicks Pasha and forces of Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, in the woods of Shaykan near Kashgil near the town of El-Obeid on 3–5 November 1883.

...

. The Mahdi's forces captured the Egyptians' equipment and overran large parts of Sudan, including Darfur and Kordofan

Kordofan ( ar, كردفان ') is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kordofan, South Kordofan and West Kordofan. In August 2005, West Kordofan State was abolished and its territory di ...

. However Egypt still maintained several strong garrisons in Sudan, including at Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

.

Appointment of Gordon

The defeat brought the Mahdi Revolt to the attention of the British government and public. The British

The defeat brought the Mahdi Revolt to the attention of the British government and public. The British Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, William Gladstone, and his War Secretary

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, Lord Hartington

Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, (23 July 183324 March 1908), styled Lord Cavendish of Keighley between 1834 and 1858 and Marquess of Hartington between 1858 and 1891, was a British statesman. He has the distinction of having ...

, did not want British troops to become involved in Sudan. If Egypt fought the war itself, they were concerned that the expense would prevent Egypt from paying the interest on its extensive debts to Britain (and France). The British put pressure on the Egyptian government to evacuate all their garrisons in Sudan, abandoning it to the Mahdists. The British soldier Major-General Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in ...

, a former Governor-General of Sudan (1876–79), was re-appointed to that post, with orders to conduct the evacuation.

Gordon's views on Sudan were radically different from Gladstone's: Gordon felt that the Mahdi's rebellion had to be defeated before it gained control of the whole of Sudan. The Mahdi claimed dominion over the entire Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

, which led Gordon to believe that the revolt would not end with control of Sudan, but would attempt to conquer Egypt and perhaps the wider region. Gordon was also concerned by the fragility of the Egyptian army, which had suffered several defeats by the Sudanese. Gordon favoured a more aggressive policy in Sudan, as did the imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

author Sir Samuel Baker

Sir Samuel White Baker, Order of the Bath, KCB, Royal Society, FRS, Royal Geographical Society, FRGS (8 June 1821 – 30 December 1893) was an English List of explorers, explorer, Officer (armed forces), officer, naturalist, big game hunter, ...

and Sir Garnet Wolseley

Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley, (4 June 183325 March 1913), was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army. He became one of the most influential and admired British generals after a series of successes in Canada, W ...

, who had commanded British forces in the 1882 war. Gordon published his views on Sudan in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' in January 1884.S. Monick, "The Political Martyr: General Gordon and the Fall of Kartum" ''Military History Journal'', "Vol 6 No Despite this, Gordon was commanded to evacuate Sudan, which he agreed to do. He was given funds of Pound sterling, £100,000 in credit and was promised "all support and cooperation in their power" by the British and Egyptian authorities. On his way to Khartoum with his assistant, Colonel John Stewart, Gordon stopped in the town of

Berber, Sudan

, nickname =

, settlement_type = Town

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, imagesize =

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, flag_size =

, image_seal ...

to address an assembly of tribal chiefs. There he made a major mistake, by revealing that the Egyptian government planned to withdraw their troops from Sudan. The tribesmen became worried by this news, which caused their loyalty to waver.

Gordon's preparations

Gordon arrived at Khartoum on 18 February 1884, finding it was safely occupied by a garrison of 7,000 Egyptian troops and 27,000 civilians. However three smaller garrisons, atSennar

Sennar ( ar, سنار ') is a city on the Blue Nile in Sudan and possibly the capital of the state of Sennar. It remains publicly unclear whether Sennar or Singa is the capital of Sennar State. For several centuries it was the capital of the F ...

, Tokar and Sinkat, were under siege by the Mahdists. Rather than evacuating Khartoum immediately, Gordon declared his intention to extricate the other garrisons, and set about administering Sudan. His first actions were to reverse several policies introduced by the Egyptians since he had last been Governor-General five years earlier: arbitrary imprisonments were cancelled, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts c ...

was halted and its instruments were destroyed, and taxes were remitted. To enlist the support of the population, Gordon re-legalised slavery in Sudan

Slavery in Sudan began in ancient times, and recently had a resurgence during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005). During the Trans-Saharan slave trade, many Nilotic peoples from the lower Nile Valley were purchased as slaves and brought ...

, despite having (unsuccessfully) attempted to abolish it in his previous term. This decision was popular in Khartoum, but caused controversy in Britain.

Seeking to bolster Khartoum's defences, Gordon then attempted to secure reinforcements. He requested a regiment of Turkish soldiers from the Ottomans, who were still the nominal overlords, which was rebuffed. He then asked the British for a unit of Muslim Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

troops, and later for 200 native British soldiers. These were also refused by the Gladstone cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

, which was still intent upon evacuation and adamant they would make no military intervention in Sudan.

Gordon began to resent the government's policy, and his telegrams to the British office in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

became more acrimonious. He declared himself honour-bound to rescue the garrisons and defend the Sudanese in Khartoum; it is unclear whether this was a deliberate attempt to delay the evacuation (or avoid it entirely). On 8 April he wrote: "I leave you with the indelible disgrace of abandoning the garrisons" and added that such a course would be "the climax of meanness".

Battle

Siege begins

Knowing that the Mahdists were closing in, Gordon ordered the strengthening of the fortifications around Khartoum. The city was protected to the north by theBlue Nile

The Blue Nile (; ) is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. It travels for approximately through Ethiopia and Sudan. Along with the White Nile, it is one of the two major tributaries of the Nile and supplies about 85.6% of the water ...

and to the west by the White Nile. To defend the river banks, he formed a flotilla of gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s from nine small paddle-wheel steamers, which had been used for communication along the river, by fitting them with guns and metal plates for armour. In the southern part of the town, which faced the open desert, he prepared an elaborate system of trench

A trench is a type of excavation or in the ground that is generally deeper than it is wide (as opposed to a wider gully, or ditch), and narrow compared with its length (as opposed to a simple hole or pit).

In geology, trenches result from ero ...

es, makeshift Fougasse-type land mine

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

s, and wire entanglements. The surrounding country was controlled by the Shagia tribe, which were thought to be hostile to the Mahdi.

On 16 March Gordon launched a unsuccessful sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warfare. ...

from Khartoum, with 200 Egyptian troops dying in the fighting. By early April 1884, the tribes north of Khartoum had risen in support of the Mahdi, including those Gordon had met at Berber. The tribesmen intercepted river traffic on the Nile and cut the telegraph cables to Cairo. Communications were not entirely halted, as individual messengers could still get through, but this effectively began the siege of Khartoum. The city could rely only on its own food stores, which were expected to last five or six months. By this time, the combined forces besieging Khartoum and the other garrisons were over 30,000 men.

From April onwards, Khartoum was cut off. With no supply of money to pay the troops or facilitate trade of food, Gordon used his credit to issue a series of promissory notes, a form of siege money. Communication with Cairo was maintained through couriers, who took several days to make the trip. Gordon also contacted the Mahdi, who rejected his attempts to negotiate a peaceful evacuation. As the siege dragged on, food stores dwindled and starvation began to set in, for both the garrison and the civilian population.

In September, the besieged forces in Khartoum made an attempt to reach the garrison at Sennar; the expedition made it out of the siege lines but was defeated by the Mahdists at Al Aylafuh, with the loss of 800 garrison troops. By the end of the month, the Mahdi moved most of his army to Khartoum, away from the outlying garrisons, more than doubling the number around the city. On of 10 September 1884, the civilian population inside Khartoum was about 34,000.

Relief expedition

Gordon's plight excited great concern in the

Gordon's plight excited great concern in the British press

Twelve daily newspapers and eleven Sunday-only weekly newspapers are distributed nationally in the United Kingdom. Others circulate in Scotland only and still others serve smaller areas. National daily newspapers publish every day except Sunday ...

, and even Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

intervened on his behalf. The government ordered Gordon to return to Cairo, alone if necessary, but he refused, saying he would not abandon the city. In July 1884, Gladstone reluctantly agreed to send an expedition to relieve Khartoum. The relief force, 1400 British troops led by Sir Garnet Wolseley, took several months to organise and did not enter Sudan until January 1885.

By then the situation in Khartoum had become desperate. Food supplies had been expected to last six months, but the siege had gone on for ten months. With supplies running low, many inhabitants died of hunger, and the defenders' morale plummeted.

As they advanced into Sudan, the relief expedition was attacked at the Battle of Abu Klea

The Battle of Abu Klea, or the Battle of Abu Tulayh took place between the dates of 16 and 18 January 1885, at Abu Klea, Sudan, between the British Desert Column and Mahdist forces encamped near Abu Klea. The Desert Column, a force of approxim ...

on 17 January. Although the Mahdists managed to break their infantry square

An infantry square, also known as a hollow square, was a historic combat formation in which an infantry unit formed in close order, usually when it was threatened with cavalry attack. As a traditional infantry unit generally formed a line to adva ...

, the British troops managed to recover and repel the attack. Two days later, the relief force was attacked again at the Battle of Abu Kru

The Battle of Abu Kru (also known as the Battle of Gubat) was part of the British Sudan campaign. It was fought on 19 January 1885, two days after the Battle of Abu Klea, between the British and the Mahdists. The British force under General Si ...

but managed to drive off the Mahdists. The Mahdi, aware of the British advance, decided to assault Khartoum before they could arrive.

Fall of Khartoum

On the night of 25–26 January an estimated 50,000 Mahdists attacked the city wall just before midnight. The Mahdists took advantage of the seasonally low level of the Nile, which allowed them to ford the river on foot. The details of the final assault are unclear, but hearsay accounts were that by 3:30 am, the Mahdists had outflanked the city wall where it met the Nile. Meanwhile another force, led by Al Nujumi, broke down the Massalamieh Gate, despite taking casualties from the land mines and barbed wire obstacles laid out by Gordon's men. The defending garrison, weakened by starvation and low morale, offered only patchy resistance. Within a few hours, the garrison were slaughtered to the last man, as were 4,000 of the town's male inhabitants. Many women and children were enslaved by the victorious Mahdists. Accounts differ as to how Gordon was killed. According to one version, when Mahdist warriors broke into the governor's palace, Gordon came outside in full uniform and disdained to fight; he was then killed with a spear, despite orders from the Mahdi to capture Gordon alive. In another version, Gordon was recognised by Mahdists while attempting to reach the neutral Austrian consulate in the city, who shot him dead in the street.

The most detailed account of his death was given by his servant Khaleel Aga Orphali, when debriefed by the British in 1898 (13 years later). According to Orphali, Gordon died fighting on the stairs leading from the first to the ground floor of the west wing of the palace. Gordon was seriously wounded by a spear that hit him in the left shoulder, but continued fighting with Orphali beside him. Orphali stated that:

Accounts differ as to how Gordon was killed. According to one version, when Mahdist warriors broke into the governor's palace, Gordon came outside in full uniform and disdained to fight; he was then killed with a spear, despite orders from the Mahdi to capture Gordon alive. In another version, Gordon was recognised by Mahdists while attempting to reach the neutral Austrian consulate in the city, who shot him dead in the street.

The most detailed account of his death was given by his servant Khaleel Aga Orphali, when debriefed by the British in 1898 (13 years later). According to Orphali, Gordon died fighting on the stairs leading from the first to the ground floor of the west wing of the palace. Gordon was seriously wounded by a spear that hit him in the left shoulder, but continued fighting with Orphali beside him. Orphali stated that:"With his life's blood pouring from his breast ..he fought his way step by step, kicking from his path the wounded and deadOrphali claimed he was then knocked unconscious, waking unharmed several hours later to find Gordon's decapitated body near to him.''A Prisoner of the Khaleefa - Ten Years Captivity at Omdurman'' (Chapman and Hall, 1899), Chapter XXV – How Gordon Died, pp. 300–324, and Appendix 2, pp. 334–337 However he died, Gordon's head was taken to the city of Omdurman, the Mahdi's headquarters, where it was shown todervish Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from fa, درویش, ''Darvīsh'') in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity A fraternity (from Latin language, Latin ''wiktionary:frater, frater'': "brother (Christian), brother"; whence, ...es ..and as he was passing through the doorway leading into the courtyard, another concealed dervish almost severed his right leg with a single blow.

Rudolf Carl von Slatin

Major-General Rudolf Anton Carl Freiherr von Slatin, Geh. Rat, (7 June 1857, in Ober Sankt Veit, Hietzing, Vienna – 4 October 1932, in Vienna) was an Anglo-Austrian soldier and administrator in the Sudan.

Early life

Rudolf Carl Slatin was ...

(a prisoner of the Mahdi who had worked for Gordon during his first term in Sudan). After it was shown to Slatin, the head was brought to the Mahdi. According to some sources, the rest of Gordon's body was dumped in the Nile.

Aftermath

Advance elements of the relief expedition arrived within sight of Khartoum two days after it fell. After discovering that they were too late, the surviving British and Egyptian troops withdrew. The Mahdi was left in control of the entire country, with the exceptions of the city ofSuakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

on the Red Sea coast and the Nile town of Wadi Halfa

Wādī Ḥalfā ( ar, وادي حلفا) is a city in the Northern state of Sudan on the shores of Lake Nubia near the border with Egypt. It is the terminus of a rail line from Khartoum and the point where goods are transferred from rail to ferr ...

on the Sudan-Egyptian border, which were garrisoned by the Anglo-Egyptian force.

After his victory, Muhammad Ahmad became the ruler of most parts of what is now Sudan and South Sudan. He established a religious state, the Mahdiyah, but died shortly afterwards in June 1885, possibly from typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

. The state he founded passed to Abdallahi ibn Muhammad

Abdullah Ibn-Mohammed Al-Khalifa or Abdullah al-Khalifa or Abdallahi al-Khalifa, also known as "The Khalifa" ( ar, c. عبدالله بن سيد محمد الخليفة; 184625 November 1899) was a Sudanese Ansar ruler who was one of the principa ...

, his chosen successor.

In the immediate aftermath of the Mahdist victory, the British press blamed Gordon's death on Gladstone, who was accused of being excessively slow to send relief to Khartoum. Gladstone had never wanted to get involved in Sudan and felt some sympathy for those Sudanese who sought to end Egyptian colonial rule. He declared in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

: "Yes, those people are struggling to be free, and they are rightly struggling to be free". Gordon's failure to conduct an immediate evacuation had not endeared him to Gladstone's government. However among the British public, Gordon was seen as a martyr and a hero. Gladstone was rebuked by Queen Victoria in a telegram, which was leaked to the public. The public outcry over Sudan soon weakened, firstly when press sensationalism of the events began to diminish, and secondly when the government announced that the war in Sudan had cost Britain £11.5 million from its military budget. Gladstone's government fell in June 1885; he regained power in December following the 1885 UK election, but lost it again in another election in 1886.

Fighting continued between Egypt and the Mahdists over the following years. Complex international events led to further European expansion into Africa, compelling the British to take a more active role in the conflict. The Anglo-Egyptian forces steadily regained their control over Sudan. In 1896, an expedition led by Herbert Kitchener

Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, (; 24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916) was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator. Kitchener came to prominence for his imperial campaigns, his scorched earth policy against the Boers, h ...

(who had sworn to avenge Gordon) was sent to reconquer the whole country. On 2 September 1898, Kitchener's troops defeated the largest Mahdist army at the Battle of Omdurman

The Battle of Omdurman was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British–Egyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief (sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert Kitchener and a Sudanese army of the M ...

. Two days later, a memorial service for Gordon was held in front of the ruins of the palace where he had died. Fourteen years after the Mahdist capture of Khartoum, the Mahdist Revolt was finally extinguished at the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat

The Battle of Umm Diwaykarat on 25 November 1899 marked the final defeat of the Mahdist State in Sudan, when Anglo-Egyptian forces under the command of Lord Kitchener defeated what was left of the Mahdist armies under the command of the Abd ...

in November 1899.

Cultural depictions

*These events are depicted in the 1966 film ''Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

'', with Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston (born John Charles Carter; October 4, 1923April 5, 2008) was an American actor and political activist.

As a Hollywood star, he appeared in almost 100 films over the course of 60 years. He played Moses in the epic film ''The Ten C ...

as General Gordon and Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

as Muhammad Ahmad.

*The Siege of Khartoum is the setting for Wilbur Smith

Wilbur Addison Smith (9 January 1933 – 13 November 2021) was a Zambian-born British-South African novelist specialising in historical fiction about international involvement in Southern Africa across four centuries, seen from the viewpoints ...

's novel ''The Triumph of the Sun'' (2005) and David Gibbins' ''Pharaoh'' (2013).

*G. A. Henty

George Alfred Henty (8 December 1832 – 16 November 1902) was an English novelist and war correspondent. He is most well-known for his works of adventure fiction and historical fiction, including ''The Dragon & The Raven'' (1886), ''For The ...

wrote a young adults' novel about the siege called ''The Dash for Khartoum'' (1892). It has been reissued and is also available to read free online aProject Gutenberg

*

Henryk Sienkiewicz

Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz ( , ; 5 May 1846 – 15 November 1916), also known by the pseudonym Litwos (), was a Polish writer, novelist, journalist and Nobel Prize laureate. He is best remembered for his historical novels, especi ...

, Polish writer and Nobel Prize winner, set his novel ''In Desert and Wilderness

''In Desert and Wilderness'' ( pl, W pustyni i w puszczy) is a popular young adult novel by the Polish author and Nobel Prize-winning novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz, written in 1911. It is the author's only novel written for children/teenagers. It ...

'' (1923) in Sudan during Mahdi's rebellion, which is integral to the plot.

*Gillian Slovo

Gillian Slovo (born 15 March 1952) is a South African-born writer who lives in the UK. She was a recipient of the Golden PEN Award.

Early life and education

Gillian Slovo was born on 15 March 1952 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Her family move ...

based her novel ''An Honourable Man'' (2012) on the established narrative of General Gordon's last days in Khartoum.Helen Davies, "Saving General Gordon: Review of Gillian Slovo’s An Honourable Man." ''Neo-Victorian Studies'' 5:2 (2012) pp. 228–23online

References

Further reading

* *Bass, Jeff D. "Of madness and empire: The rhetor as 'fool' in the Khartoum siege journals of Charles Gordon, 1884." ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' 93.4 (2007): 449–469. *Blunt, Wilfrid Scawen. ''Gordon at Khartoum: Being a Personal Narrative of Events'' (1923online

*Buchan, John. ''Gordon at Khartoum'' (1934)

online

Internet Archive *Chenevix Trench, Charles. ''The Road to Khartoum: a life of General Charles Gordon'' (1979

online free to borrow

*Elton, Godfrey Elton Baron. ''Gordon of Khartoum: The Life of General Charles Gordon'' (Knopf, 1954). *Nicoll, Fergus. ''The Sword of the Prophet: the Mahdi of Sudan and the Death of General Gordon'' (Sutton Publishing, 2004). *Miller, Brook. "Our Abdiel: The British Press and the Lionization of 'Chinese' Gordon." ''Nineteenth-Century Prose'' 32.2 (2005): 127

online

*Snook, Colonel Mike. ''Beyond the Reach of Empire: Wolseley's Failed Campaign to save Gordon and Khartoum'' (Frontline Books, 2013). {{Authority control 1884 in Sudan 1885 in Sudan Conflicts in 1884 Conflicts in 1885

Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

History of Khartoum

Khartoum 1884