Second Voyage Of The HMS Beagle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'', from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836, was the second survey expedition of HMS ''Beagle'', under captain

When the

When the

The 27-year-old FitzRoy had hopes of commanding a second expedition to continue the South American survey, but when he heard that the

The 27-year-old FitzRoy had hopes of commanding a second expedition to continue the South American survey, but when he heard that the

Darwin fitted well the expectations of a gentleman natural philosopher and was well trained as a naturalist. When he had studied geology in his second year at Edinburgh, he had found it dull, but from Easter to August 1831, he learned a great deal with Sedgwick and developed a strong interest during their geological field trip. On 24 August Henslow wrote to Darwin:

Darwin fitted well the expectations of a gentleman natural philosopher and was well trained as a naturalist. When he had studied geology in his second year at Edinburgh, he had found it dull, but from Easter to August 1831, he learned a great deal with Sedgwick and developed a strong interest during their geological field trip. On 24 August Henslow wrote to Darwin:

Charles Darwin had been told that ''Beagle'' was expected to sail about the end of September 1831, but fitting out took longer. The Admiralty Instructions were received on 14 November, and on 23 November, she was moved to anchorage, ready to depart. Repeated Westerly gales caused delays, and forced them to turn back after departing on 10 and 21 December. Drunkenness at Christmas lost another day. Finally, on the morning of 27 December, ''Beagle'' left its anchorage in the Barn Pool, under Mount Edgecumbe on the west side of

Charles Darwin had been told that ''Beagle'' was expected to sail about the end of September 1831, but fitting out took longer. The Admiralty Instructions were received on 14 November, and on 23 November, she was moved to anchorage, ready to depart. Repeated Westerly gales caused delays, and forced them to turn back after departing on 10 and 21 December. Drunkenness at Christmas lost another day. Finally, on the morning of 27 December, ''Beagle'' left its anchorage in the Barn Pool, under Mount Edgecumbe on the west side of

Bahía Blanca, September—October 1832. With assistance (possibly from the young sailor Syms Covington acting as his servant), Darwin collected numerous fossils over several days, amusing others with "the cargoes of apparent rubbish which he frequently brought on board". Much of the second day was taken up with excavating a large skull which Darwin found embedded in soft rock, and seemed to him to be allied to the

They reached

They reached

p. 36

a typical Glyptodont tail. His notes included a page showing his realisation that the cliff banks of the rivers exposed two strata formed in an

p. 37

/ref> Back at Montevideo, Darwin was introduced to

Back at Montevideo, Darwin was introduced to

''Beagle'' and ''Adventure'' now surveyed the Straits of Magellan before sailing north up the west coast, reaching

''Beagle'' and ''Adventure'' now surveyed the Straits of Magellan before sailing north up the west coast, reaching  They arrived at the port of

They arrived at the port of

''Beagle'' sailed on to Charles Island. By chance, they were greeted by the "Englishman"

''Beagle'' sailed on to Charles Island. By chance, they were greeted by the "Englishman"

In Cape Town, missionaries were being accused of causing racial tension and profiteering, and after ''Beagle'' set to sea on 18 June, FitzRoy wrote an open letter to the

In opposing transmutation, Lyell had proposed that varieties arose due to changes in the environment, but these varieties lived in similar conditions though each on its own island. Darwin had just reviewed similar inconsistencies with mainland bird genera such as '' Pteroptochos''. Though his suspicions about the

On the stormy night of 2 October 1836, immediately after arriving in Falmouth, Darwin set off on the Royal Mail

On the stormy night of 2 October 1836, immediately after arriving in Falmouth, Darwin set off on the Royal Mail

Over the following years, Owen published descriptions of the most important fossils, naming several as new species. He described the fossils from

Over the following years, Owen published descriptions of the most important fossils, naming several as new species. He described the fossils from

Darwin Online

Darwin's publications, private papers and bibliography, supplementary works including biographies, obituaries and reviews. Free to use, includes items not in public domain. *; public domain

Darwin Correspondence Project

Text and notes for most of his letters

Darwin in Galapagos: Footsteps to a New World

{{DEFAULTSORT:Second Voyage Of Hms Beagle Voyage on HMS ''Beagle'' History of evolutionary biology Global expeditions 1831 in the United Kingdom 1833 in Argentina 1830s in science HMS Beagle Expeditions from the United Kingdom

Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

who had taken over command of the ship on its first voyage after the previous captain, Pringle Stokes

Pringle Stokes (23 April 1793 – 12 August 1828) was a British naval officer who served in HMS '' Owen Glendower'' on a voyage around Cape Horn to the Pacific coast of South America, and on the West African coast fighting the slave trade.

He th ...

, committed suicide. FitzRoy had thought of the advantages of having someone onboard who could investigate geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

, and sought a naturalist to accompany them as a supernumerary

Supernumerary means "exceeding the usual number".

Supernumerary may also refer to:

* Supernumerary actor, a performer in a film, television show, or stage production who has no role or purpose other than to appear in the background, more commonl ...

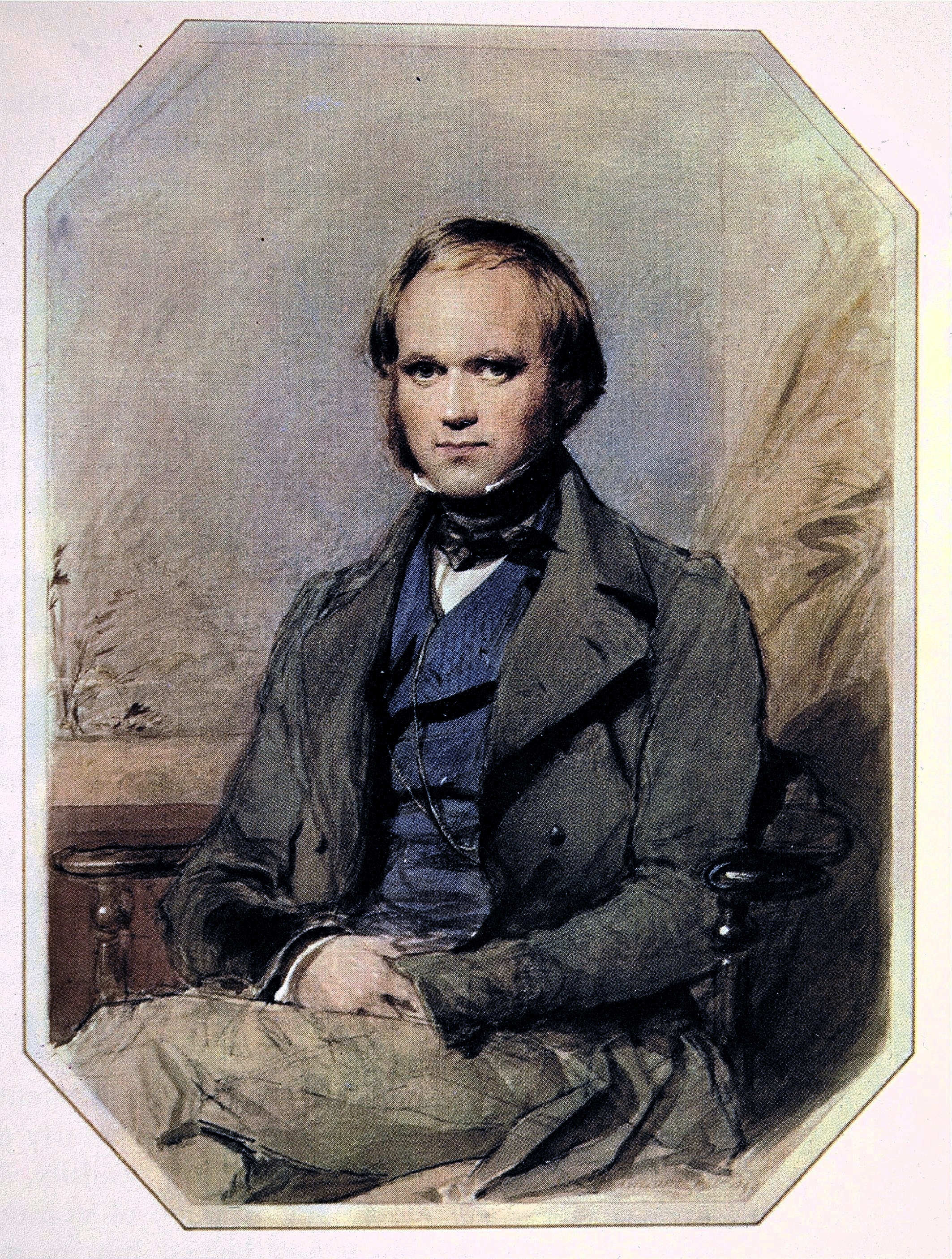

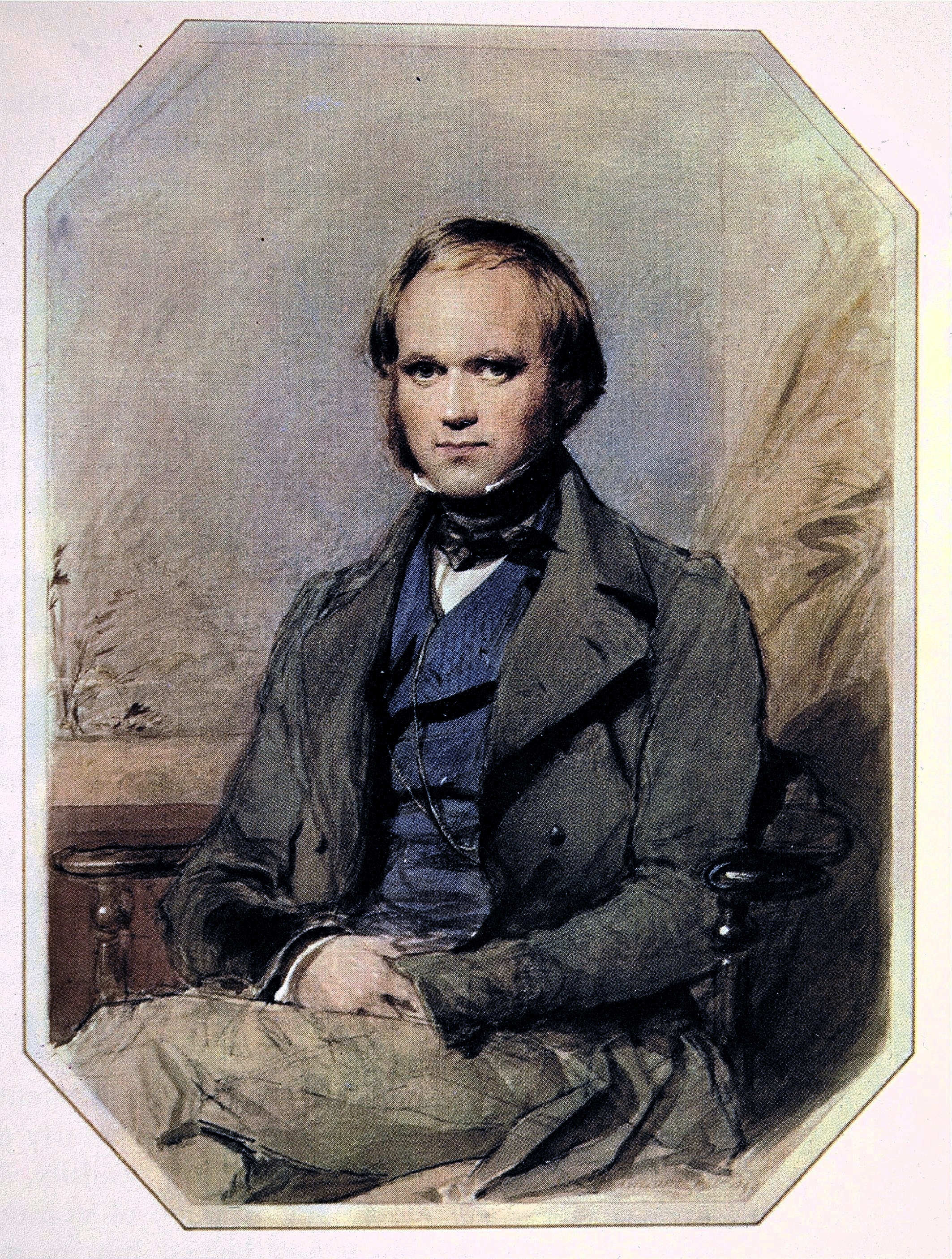

. At the age of 22, the graduate Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

hoped to see the tropics before becoming a parson

A parson is an ordained Christian person responsible for a small area, typically a parish. The term was formerly often used for some Anglican clergy and, more rarely, for ordained ministers in some other churches. It is no longer a formal term ...

and accepted the opportunity. He was greatly influenced by reading Charles Lyell's ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830–1833. Ly ...

'' during the voyage. By the end of the expedition, Darwin had made his name as a geologist and fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

collector and the publication of his journal (later known as ''The Voyage of the Beagle

''The Voyage of the Beagle'' is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his ''Journal and Remarks'', bringing him considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of ''The Narrative ...

'') gave him wide renown as a writer.

''Beagle'' sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, and then carried out detailed hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/ offshore oil drilling and related activities. Strong emphasis is placed ...

s around the coasts of southern South America, returning via Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

and Australia after having circumnavigated the Earth. The initial offer to Darwin told him the voyage would last two years; it lasted almost five.

Darwin spent most of this time exploring on land: three years and three months land, 18 months at sea. Early in the voyage, Darwin decided that he could write a geology book, and he showed a gift for theorising. At Punta Alta

Punta Alta is a city in Argentina, about 20 kilometers southeast of Bahía Blanca. It has a population of 57,293. It is the capital ("cabecera") of the Coronel Rosales Partido. It was founded on 2 July 1898.

The city is located near the Atlant ...

in Argentina, he made a major find of gigantic fossils of extinct mammals, then known from very few specimens. He collected and made detailed observations of plants and animals. His findings undermined his belief in the doctrine that species are fixed, and provided the basis for ideas which came to him when back in England, leading to his theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

.

Aims of the expedition

When the

When the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

ended in 1815, the ''Pax Britannica

''Pax Britannica'' (Latin for "British Peace", modelled after '' Pax Romana'') was the period of relative peace between the great powers during which the British Empire became the global hegemonic power and adopted the role of a " global pol ...

'' saw seafaring nations competing in colonisation and rapid industrialisation. The logistics of supply and growing commerce needed reliable information about sea routes, but existing nautical chart

A nautical chart is a graphic representation of a sea area and adjacent coastal regions. Depending on the scale of the chart, it may show depths of water and heights of land ( topographic map), natural features of the seabed, details of the co ...

s were incomplete and inaccurate. Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

ended Spain's monopoly over trade, and the UK's 1825 commercial treaty with Argentina recognised its independence, increasing the naval and commercial significance of the east coast of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

. The Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

instructed Commander King to make an accurate hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/ offshore oil drilling and related activities. Strong emphasis is placed ...

of "the Southern Coasts of the Peninsula of South America, from the southern entrance of the River Plata, round to Chilóe; and of Tierra del Fuego". As Darwin wrote of his voyage, "The object of the expedition was to complete the survey of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, commenced under Captain King in 1826 to 1830—to survey the shores of Chile, Peru, and of some islands in the Pacific—and to carry a chain of chronometrical measurements round the World." The expeditions also had diplomatic objectives, visiting disputed territories.

An Admiralty memorandum set out the detailed instructions. The first requirement was to resolve disagreements in the earlier surveys about the longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lette ...

of Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

, which was essential as the base point for meridian distances. The accurate marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), or in the modern ...

s needed to determine longitude had only become affordable since 1800; ''Beagle'' carried 22 chronometers to allow corrections. The ship was to stop at specified points for a four-day rating of the chronometers and to check them by astronomical observations: it was essential to take observations at Porto Praya

Praia (, Portuguese for "beach") is the capital and largest city of Cape Verde.Fernando de Noronha

Fernando de Noronha () is an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, part of the State of Pernambuco, Brazil, and located off the Brazilian coast. It consists of 21 islands and islets, extending over an area of . Only the eponymous main island is in ...

to calibrate against the previous surveys of William Fitzwilliam Owen

Vice Admiral William Fitzwilliam Owen (17 September 1774 – 3 November 1857), was a British naval officer and explorer. He is best known for his exploration of the west and east African coasts, discovery of the Seaflower Channel off the co ...

and Henry Foster. It was important to survey the extent of the Abrolhos Archipelago

The Abrolhos Archipelago () are a group of 5 small islands with coral reefs off the southern coast of Bahia state in the northeast of Brazil, between 17º25’—18º09’ S and 38º33’—39º05’ W. Caravelas is the nearest town. Their name c ...

reefs, shown incorrectly in Albin Roussin

Albin Reine Roussin (21 April 1781 – 21 February 1854) was a French admiral and statesman.

Republic and Empire

His father was a lawyer who was arrested during the French Revolution when Roussin was aged twelve. He left home in Dijon and tra ...

's survey, then proceed to Rio de Janeiro to decide the exact longitude of Villegagnon Island

Villegagnon Island (former Serigipe Island—original Portuguese: ''Ilha de Villegagnon''—also known in English as: Villegaignon Island, Island of Villegagnon or Island of Villegaignon) is located near the mouth of the large Guanabara Bay, in th ...

.

The real work of the survey was then to commence south of the Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and fo ...

, with return trips to Montevideo for supplies; details were given of priorities, including surveying Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

and approaches to harbours on the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

. The west coast was then to be surveyed as far north as time and resources permitted. The commander would then determine his own route west: season permitting, he could survey the Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuador ...

. Then, ''Beagle'' was to proceed to Point Venus, Tahiti, and on to Port Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman Sea ...

, Australia, which were known points to verify the chronometers.

No time was to be wasted on elaborate drawings; charts and plans should have notes and simple views of the land as seen from the sea showing measured heights of hills. Continued records of tides and meteorological conditions were also required. An additional suggestion was for a geological survey of a circular coral atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon partially or completely. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical oceans and seas where corals can gr ...

in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

including its profile and of tidal flows, to investigate the formation of such coral reefs.

Context and preparations

The previous survey expedition to South America involved HMS ''Adventure'' and HMS ''Beagle'' under the overall command of the Australian CommanderPhillip Parker King

Rear Admiral Phillip Parker King, FRS, RN (13 December 1791 – 26 February 1856) was an early explorer of the Australian and Patagonian coasts.

Early life and education

King was born on Norfolk Island, to Philip Gidley King and Ann ...

. During the survey, ''Beagle'' captain, Pringle Stokes

Pringle Stokes (23 April 1793 – 12 August 1828) was a British naval officer who served in HMS '' Owen Glendower'' on a voyage around Cape Horn to the Pacific coast of South America, and on the West African coast fighting the slave trade.

He th ...

, committed suicide and command of the ship was given to the young aristocrat Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

, a nephew of George FitzRoy, 4th Duke of Grafton

George Henry FitzRoy, 4th Duke of Grafton, KG (14 January 1760 – 28 September 1844), styled Earl of Euston until 1811, was a British peer and Whig politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1782 to 1811 when he succeeded to the Dukedo ...

. When a ship's boat was taken by the natives of Tierra del Fuego, FitzRoy tried taking some of them hostage, and after this failed he got occupants of a canoe to put another on the ship in exchange for buttons. He brought four of them back to England to be given a Christian education, with the idea that they could eventually become missionaries. One died of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. After ''Beagle'' return to Devonport dockyard on 14 October 1830, Captain King retired.

The 27-year-old FitzRoy had hopes of commanding a second expedition to continue the South American survey, but when he heard that the

The 27-year-old FitzRoy had hopes of commanding a second expedition to continue the South American survey, but when he heard that the Lords of the Admiralty

This is a list of Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty (incomplete before the Restoration, 1660).

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty were the members of The Board of Admiralty, which exercised the office of Lord High Admiral when it was ...

no longer supported this, he grew concerned about how to return the Fuegians. He made an agreement with the owner of a small merchant-vessel to take himself and five others back to South America, but a kind uncle heard of this and contacted the Admiralty. Soon afterwards, FitzRoy heard that he was to be appointed commander of HMS ''Chanticleer'' to go to Tierra del Fuego, but due to her poor condition, ''Beagle'' was substituted. On 27 June 1831, FitzRoy was commissioned as commander of the voyage, and Lieutenants John Clements Wickham

John Clements Wickham (21 November 17986 January 1864) was a Scottish explorer, naval officer, magistrate and administrator. He was first lieutenant on during its second survey mission, 1831–1836, under captain Robert FitzRoy. The young ...

and Bartholomew James Sulivan

Admiral Sir Bartholomew James Sulivan, (18 November 1810 – 1 January 1890) was a British naval officer and hydrographer. He was a leading advocate of the value of nautical surveying in relation to naval operations.

Sulivan was born at Mylor ...

were both appointed.

Captain Francis Beaufort, the Hydrographer of the Admiralty, was invited to decide on the use that could be made of the voyage to continue the survey, and he discussed with FitzRoy plans for a voyage of several years, including a continuation of the trip around the world to establish median distances. ''Beagle'' was commissioned on 4 July 1831, under the command of Captain FitzRoy, who promptly spared no expense in having ''Beagle'' extensively refitted. ''Beagle'' was immediately taken into dock for extensive rebuilding and refitting. As she required a new deck, FitzRoy had the upper-deck raised considerably, by aft and forward. The ''Cherokee''-class brig-sloops had the reputation of being "coffin brigs", which handled badly and were prone to sinking. By helping the decks to drain more quickly with less water collecting in the gunnels, the raised deck gave ''Beagle'' better handling and made her less liable to become top-heavy and capsize. Additional sheathing to the hull added about seven tons to her burthen and perhaps fifteen to her displacement.

The ship was one of the first to test the lightning conductor

A lightning rod or lightning conductor (British English) is a metal rod mounted on a structure and intended to protect the structure from a lightning strike. If lightning hits the structure, it will preferentially strike the rod and be conducte ...

invented by William Snow Harris

Sir William Snow Harris (1 April 1791 – 22 January 1867) was a British physician and electrical researcher, nicknamed Thunder-and-Lightning Harris, and noted for his invention of a successful system of lightning conductors for ships. It took ...

. FitzRoy obtained five examples of the '' Sympiesometer'', a kind of mercury-free barometer

A barometer is a scientific instrument that is used to measure air pressure in a certain environment. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Many measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis ...

patented by Alexander Adie

Alexander James Adie FRSE MWS (1775, Edinburgh – 4 December 1858, Edinburgh) was a Scottish maker of medical instruments, optician and meteorologist. He was the inventor of the sympiesometer, patented in 1818.

Life

He was born the son of J ...

and favoured by FitzRoy as giving the accurate readings required by the Admiralty.

In addition to its officers and crew, ''Beagle'' carried several supernumeraries, passengers without an official position. FitzRoy employed a mathematical instrument maker to maintain his 22 marine chronometers kept in his cabin, as well as engaging the artist/draughtsman Augustus Earle

Augustus Earle (1793–1838) was a British painter. Unlike earlier artists who worked outside Europe and were employed on voyages of exploration or worked abroad for wealthy, often aristocratic patrons, Earle was able to operate quite indepen ...

to go in a private capacity. The three Fuegians taken on the previous voyage were going to be returned to Tierra del Fuego on ''Beagle'' together with the missionary Richard Matthews.

Naturalist and geologist

For Beaufort and the leadingCambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

"gentlemen of science" the opportunity for a naturalist to join the expedition fitted with their drive to revitalise British government policy on science. This elite disdained research done for money and felt that natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

was for gentlemen, not tradesmen

A tradesman, tradeswoman, or tradesperson is a skilled worker that specializes in a particular trade (occupation or field of work). Tradesmen usually have work experience, on-the-job training, and often formal vocational education in contrast ...

. The officer class of the Army and Navy provided a way to ascend this hierarchy; the ship's surgeon

A naval surgeon, or less commonly ship's doctor, is the person responsible for the health of the ship's company aboard a warship. The term appears often in reference to Royal Navy's medical personnel during the Age of Sail.

Ancient uses

Special ...

often collected specimens on voyages, and Robert McCormick had secured the position on ''Beagle'' after taking part in earlier expeditions and studying natural history. A sizeable collection had considerable social value, attracting wide public interest, and McCormick aspired to fame as an exploring naturalist. Collections made by the ship's surgeon and other officers were government property, though the Admiralty was not consistent on this, and went to important London establishments, usually the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. The Admiralty instructions for the first voyage had required officers "to use their best diligence in increasing the Collections in each ship: the whole of which must be understood to belong to the Public", but on the second voyage this requirement was omitted, and the officers were free to keep all the specimens for themselves.

FitzRoy's journal written during the first voyage noted that, while investigating magnetic rocks near the Barbara Channel, he regretted "that no person in the vessel was skilled in mineralogy, or at all acquainted with geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

", to make use of the opportunity of "ascertaining the nature of the rocks and earths" of the areas surveyed. FitzRoy decided that on any similar future expedition, he would "endeavour to carry out a person qualified to examine the land; while the officers, and myself, would attend to hydrography

Hydrography is the branch of applied sciences which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of oceans, seas, coastal areas, lakes and rivers, as well as with the prediction of their change over time, for the primar ...

." This indicated a need for a naturalist qualified to examine geology, who would spend considerable periods onshore away from the ship. McCormick lacked expertise in geology and had to attend to his duties on the ship.

FitzRoy knew that commanding a ship could involve stress and loneliness. He was aware of his uncle Viscount Castlereagh's suicide due to stress from overwork, as well as Captain Stokes's suicide. This was to be the first time that FitzRoy would be fully in charge of a ship with no commanding officer or second captain to consult. It has been suggested that he felt the need for a gentleman companion who shared his scientific interests and could dine with him as an equal, although there is no direct evidence to support this. Professor John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow (6 February 1796 – 16 May 1861) was a British priest, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to his pupil Charles Darwin.

Early life

Henslow was born at Rochester, Kent, the son of a solicit ...

described the position "more as a companion than a mere collector", but this was an assurance that FitzRoy would treat his guest as a gentleman naturalist. Several other ships at this period carried unpaid civilians as naturalists.

Early in August, FitzRoy discussed this position with Beaufort, who had a scientific network of friends at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

. At Beaufort's request, mathematics lecturer George Peacock wrote from London to Henslow about this "rare opportunity for a naturalist", saying that an "offer has been made to me to recommend a proper person to go out as a naturalist with this expedition", and suggesting the Reverend Leonard Jenyns

Leonard Jenyns (25 May 1800 – 1 September 1893) was an English clergyman, author and naturalist. He was forced to take on the name Leonard Blomefield to receive an inheritance. He is chiefly remembered for his detailed phenology observations ...

. Though Jenyns nearly accepted and even packed his clothes, he had concerns about his obligations as vicar of Swaffham Bulbeck and about his health, therefore Jenyns declined the offer. Henslow briefly thought of going, but his wife "looked so miserable" that he quickly dropped the idea. Both recommended bringing the 22-year-old Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, who was on a geology field trip with Adam Sedgwick. He had just completed the ordinary Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four year ...

degree which was a prerequisite for his intended career as a parson

A parson is an ordained Christian person responsible for a small area, typically a parish. The term was formerly often used for some Anglican clergy and, more rarely, for ordained ministers in some other churches. It is no longer a formal term ...

.

Offer of place to Darwin

Darwin fitted well the expectations of a gentleman natural philosopher and was well trained as a naturalist. When he had studied geology in his second year at Edinburgh, he had found it dull, but from Easter to August 1831, he learned a great deal with Sedgwick and developed a strong interest during their geological field trip. On 24 August Henslow wrote to Darwin:

Darwin fitted well the expectations of a gentleman natural philosopher and was well trained as a naturalist. When he had studied geology in his second year at Edinburgh, he had found it dull, but from Easter to August 1831, he learned a great deal with Sedgwick and developed a strong interest during their geological field trip. On 24 August Henslow wrote to Darwin:

...that I consider you to be the best qualified person I know of who is likely to undertake such a situation— I state this not on the supposition of yr. being a finished Naturalist, but as amply qualified for collecting, observing, & noting any thing worthy to be noted in Natural History. Peacock has the appointment at his disposal & if he can not find a man willing to take the office, the opportunity will probably be lost— Capt. F. wants a man (I understand) more as a companion than a mere collector & would not take any one however good a Naturalist who was not recommended to him likewise as a ''gentleman''. ... The Voyage is to last 2 yrs. & if you take plenty of Books with you, any thing you please may be done ... there never was a finer chance for a man of zeal & spirit... Don't put on any modest doubts or fears about your disqualifications for I assure you I think you are the very man they are in search of.The letter went first to George Peacock, who quickly forwarded it to Darwin with further details, confirming that the "ship sails about the end of September". Peacock had discussed the offer with Beaufort, "he entirely approves of it & you may consider the situation as at your absolute disposal". When Darwin returned home from the field trip late on 29 August and opened the letters, his father objected strongly to the voyage so, the next day, he wrote declining the offer and left to go shooting at the estate of his uncle

Josiah Wedgwood II

Josiah Wedgwood II (3 April 1769 – 12 July 1843), the son of the English potter Josiah Wedgwood, continued his father's firm and was a Member of Parliament (MP) for Stoke-upon-Trent from 1832 to 1835. He was an abolitionist, and detested slav ...

. With Wedgwood's help, Darwin's father was persuaded to relent and fund his son's expedition, and on Thursday 1 September, Darwin wrote to Beaufort accepting the offer. That day, Beaufort wrote to tell FitzRoy that his friend Peacock had "succeeded in getting a 'Savant

Savant syndrome () is a rare condition in which someone with significant mental disabilities demonstrates certain abilities far in excess of average. The skills that savants excel at are generally related to memory. This may include rapid calcu ...

' for you—A Mr Darwin grandson of the well known philosopher and poet—full of zeal and enterprize and having contemplated a voyage on his own account to S. America". On Friday, Darwin left for Cambridge, where he, the next day, got advice on preparations of the voyage and references to experts by Henslow.

Alexander Charles Wood (an undergraduate whose tutor was Peacock) wrote from Cambridge to his cousin FitzRoy to recommend Darwin. Around midday on Sunday 4 September, Wood received FitzRoy's response, "straightforward and gentlemanlike" but strongly against Darwin joining the expedition; both Darwin and Henslow then "gave up the scheme". Darwin went to London anyway, and next morning met FitzRoy, who explained that he had promised the place to his friend Mr. Chester (possibly the novelist Harry Chester

Harry Chester (1 October 1806 – 5 October 1868) was a British civil servant who spent most of his career in the Privy Council Office.

He published one book, ''The Lay of the Lady Ellen, a tale of 1834'', and is best remembered as the founder of ...

), but Chester had turned it down in a letter received not five minutes before Darwin arrived. FitzRoy emphasised the difficulties, including cramped conditions and plain food. Darwin would be on the Admiralty's books to get provisions (worth £40 a year) and, like the ship's officers and captain, would pay £30 a year towards the mess bill. Including outfitting, the cost to him was unlikely to reach £500. The ship would sail on 10 October, and would probably be away for three years. They talked and dined together, and soon found each other agreeable. The Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

FitzRoy had been cautious at the prospect of companionship with this unknown young gentleman of Whig background, and later admitted that his letter to Wood was "to throw cold water on the scheme" in "a sudden horror of the chances of having somebody he should not like on board". He half-seriously told Darwin later that, as "an ardent disciple of Lavater

Johann Kaspar (or Caspar) Lavater (; 15 November 1741 – 2 January 1801) was a Swiss poet, writer, philosopher, physiognomist and theologian.

Early life

Lavater was born in Zürich, and was educated at the '' Gymnasium'' there, where J. J. Bo ...

", he had nearly rejected Darwin on the phrenological

Phrenology () is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.Wihe, J. V. (2002). "Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking." In ''Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience'', pp. 195–203. C ...

basis that the shape (or physiognomy

Physiognomy (from the Greek , , meaning "nature", and , meaning "judge" or "interpreter") is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. The term can also refer to the genera ...

) of Darwin's nose indicated a lack of determination.

Darwin's preparations

While he continued to get acquainted with FitzRoy, going shopping together, Darwin rushed around to arrange his supplies and equipment. He took advice from experts on specimen preservation includingWilliam Yarrell

William Yarrell (3 June 1784 – 1 September 1856) was an English zoologist, prolific writer, bookseller and naturalist admired by his contemporaries for his precise scientific work.

Yarrell is best known as the author of ''The History of Br ...

at the Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats. It was founded in 1826. Since 1828, it has maintained the London Zoo, and since 1931 Whipsnade Park.

History

On 29 ...

, Robert Brown at the British Museum, Captain Phillip Parker King

Rear Admiral Phillip Parker King, FRS, RN (13 December 1791 – 26 February 1856) was an early explorer of the Australian and Patagonian coasts.

Early life and education

King was born on Norfolk Island, to Philip Gidley King and Ann ...

who led the first expedition, and invertebrate anatomist Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 – 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

who had tutored Darwin at Edinburgh. Yarrell gave invaluable advice and bargained with shopkeepers, so Darwin paid £50 for two pistols and a rifle, while FitzRoy had spent £400 on firearms. On Sunday, 11 September, FitzRoy and Darwin took the steam packet for Portsmouth. Darwin was not seasick and had a pleasant "sail of three days". For the first time, he saw the "very small" cramped ship, met the officers, and was glad to get a large cabin, shared with the assistant surveyor John Lort Stokes

Admiral John Lort Stokes, RN (1 August 1811 – 11 June 1885)Although 1812 is frequently given as Stokes's year of birth, it has been argued by author Marsden Hordern that Stokes was born in 1811, citing a letter by fellow naval officer Crawford ...

. On Friday, Darwin rushed back to London, "250 miles in 24 hours", and on via Cambridge and St. Albans, travelling on the Wonder coach all day on 22 September to arrive in Shrewsbury that evening, then after a last brief visit to family and friends left for London on 2 October. Delays to ''Beagle'' gave Darwin an extra week to consult experts and complete packing his baggage. After sending his heavy goods down by steam packet, he took the coach along with Augustus Earle

Augustus Earle (1793–1838) was a British painter. Unlike earlier artists who worked outside Europe and were employed on voyages of exploration or worked abroad for wealthy, often aristocratic patrons, Earle was able to operate quite indepen ...

and arrived at Devonport on 24 October.

The geologist Charles Lyell asked FitzRoy to record observations on geological features such as erratic boulders. Before they left England, FitzRoy gave Darwin a copy of the first volume of Lyell's ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830–1833. Ly ...

'' which explained features as the outcome of a gradual process taking place over extremely long periods of time. In his autobiography, Darwin recalled Henslow giving advice at this time to obtain and study the book, "but on no account to accept the views therein advocated".

Darwin's position as a naturalist on board was as a self-funded guest with no official appointment, and he could leave the voyage at any suitable stage. At the outset, George Peacock had advised that "The Admiralty are not disposed to give a salary, though they will furnish you with an official appointment & every : if a salary should be required however I am inclined to think that it would be granted". Far from wanting this, Darwin's concern was to maintain control over his collection. He was even reluctant to be on the Admiralty's books for victuals

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or fungal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ing ...

until he got assurances from FitzRoy and Beaufort that this would not affect his rights to assign his specimens.

Beaufort initially thought specimens ought to go to the British Museum, but Darwin had heard of many left waiting to be described, including botanical specimens from the first ''Beagle'' voyage. Beaufort assured him that he "should have no difficulty" as long as he "presented them to some public body" such as the Zoological

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and dis ...

or Geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other E ...

societies. Henslow had set up the small Cambridge Philosophical Society

The Cambridge Philosophical Society (CPS) is a scientific society at the University of Cambridge. It was founded in 1819. The name derives from the medieval use of the word philosophy to denote any research undertaken outside the fields of la ...

museum, Darwin told him that new finds should go to the "largest & most central collection" rather than a "Country collection, let it be ever so good", but soon expressed "hope to be able to assist the Philosoph. Society" with some specimens.

FitzRoy arranged transport of specimens to England as official cargo on the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

Packet Service, at no cost to Darwin even though it was his private collection. Henslow agreed to store them at Cambridge, and Darwin confirmed with him arrangements for land carriage from the port, to be funded by Darwin's father.

Darwin's work on the expedition

The captain had to record his survey in painstaking paperwork, and Darwin too kept a daily log as well as detailed notebooks of his finds and speculations, and a diary which became his journal. Darwin's notebooks show complete professionalism that he had probably learnt at theUniversity of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

when making natural history notes while exploring the shores of the Firth of Forth with his brother Erasmus in 1826 and studying marine invertebrates with Robert Edmund Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 – 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

for a few months in 1827. Darwin had also collected beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

s at Cambridge, but he was a novice in all other areas of natural history. During the voyage, Darwin investigated small invertebrates while collecting specimens of other creatures for experts to examine and describe once ''Beagle'' had returned to England. More than half of his carefully organised zoology notes deal with marine invertebrates. The notes also record closely reasoned interpretations of what he found about their complex internal anatomy while dissecting specimens under his microscope and small experiments on their response to stimulation. His onshore observations included intense, analytical comments on possible reasons for the behaviour, distribution, and relation to their environment of the creatures he saw. He made good use of the ship's excellent library of books on natural history but continually questioned their correctness.

Geology was Darwin's "principal pursuit" on the expedition, and his notes on that subject were almost four times larger than his zoology notes, although he kept extensive records on both. During the voyage, he wrote to his sister that "there is nothing like geology; the pleasure of the first days partridge shooting or first days hunting cannot be compared to finding a fine group of fossil bones, which tell their story of former times with almost a living tongue". To him, investigating geology brought reasoning into play and gave him opportunities for theorising.

Voyage

Plymouth Sound

Plymouth Sound, or locally just The Sound, is a deep inlet or sound in the English Channel near Plymouth in England.

Description

Its southwest and southeast corners are Penlee Point in Cornwall and Wembury Point in Devon, a distance of abou ...

and set out on its surveying expedition.

Atlantic islands

''Beagle'' touched at Madeira for a confirmed position without stopping. Then on 6 January, it reachedTenerife

Tenerife (; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands. It is home to 43% of the total population of the archipelago. With a land area of and a population of 978,100 inhabitants as of Janu ...

in the Canary Islands but was quarantined

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

there because of cholera in England. Although tantalisingly near to the town of Santa Cruz, to Darwin's intense disappointment, they were denied landing. With improving weather conditions, they sailed on. On 10 January, Darwin tried out a plankton net

A plankton net is equipment used for collecting samples of plankton in standing bodies of water. It consists of a towing line and bridles, nylon mesh net, and a cod end. Plankton nets are considered one of the oldest, simplest and least expensi ...

he had devised to be towed behind the ship—only the second recorded use of such a net (after use by John Vaughan Thompson

John Vaughan Thompson FLS (19 November 1779 – 21 January 1847) was a British military surgeon, marine biologist, zoologist, botanist, and published naturalist.

Early years

John Vaughan Thompson was born in British controlled Brooklyn on Lon ...

in 1816). Next day, he noted the great number of animals collected far from land and wrote: "Many of these creatures so low in the scale of nature are most exquisite in their forms & rich colours. — It creates a feeling of wonder that so much beauty should be apparently created for such little purpose."

Six days later, they made their first landing at Praia on the volcanic island of Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

in the Cape Verde Islands. It is here that Darwin's description in his published ''Journal

A journal, from the Old French ''journal'' (meaning "daily"), may refer to:

*Bullet journal, a method of personal organization

*Diary, a record of what happened over the course of a day or other period

*Daybook, also known as a general journal, a ...

'' begins. His initial impression was of a desolate and sterile volcanic island. However, upon visiting the town, he came to a deep valley where he "first saw the glory of tropical vegetation" and had "a glorious day", finding overwhelming novelty in the sights and sounds. FitzRoy set up tents and an observatory on Quail Island to determine the exact position of the islands, while Darwin collected numerous sea animals, delighting in vivid tropical corals in tidal pools, and investigating the geology of Quail Island. Though Daubeny's book in ''Beagle'' library described the volcanic geology of the Canary Islands, it said that the structure of the Cape Verde Islands was "too imperfectly known". Darwin saw Quail Island as his key to understanding the structure of St. Jago and made careful studies of its stratigraphy in the way he had learnt from Adam Sedgwick. He collected specimens and described a white layer of hard white rock formed from crushed coral and seashells lying between layers of black volcanic rocks, and noted a similar white layer running horizontally in the black cliffs of St. Jago at above sea level. The seashells were, as far as he could tell, "the same as those of present day". He speculated that in geologically recent times a lava flow had covered this shell sand on the sea bed, and then the strata had slowly risen to their present level. Charles Lyell's ''Principles of Geology'' presented a thesis of gradual rising and falling of the Earth's crust illustrated by the changing levels of the Temple of Serapis. Darwin implicitly supported Lyell by remarking that "Dr. Daubeny when mentioning the present state of the temple of Serapis. doubts the possibility of a surface of country being raised without cracking buildings on it. – I feel sure at St Jago in some places a town might have been raised without injuring a house." Later, in his first letter to Henslow, he wrote that "The geology was preeminently interesting & I believe quite new: there are some facts on a large scale of upraised coast ... that would interest Mr. Lyell." While still on the island, Darwin was inspired to think of writing a book on geology, and later wrote of "seeing a thing never seen by Lyell, one yet saw it partially through his eyes".

''Beagle'' surgeon Robert McCormick sought fame and fortune as an explorer. When they first met at the start of the voyage, Darwin had commented that "My friend cCormickis an ass, but we jog on very amicably". They walked into the countryside of St. Jago together, and Darwin, influenced by Lyell, found the surgeon's approach old-fashioned. They found a remarkable baobab

''Adansonia'' is a genus made up of eight species of medium-to-large deciduous trees known as baobabs ( or ). They are placed in the Malvaceae family, subfamily Bombacoideae. They are native to Madagascar, mainland Africa, and Australia.Trop ...

tree, which FitzRoy measured and sketched. Darwin went on subsequent "riding expeditions" with Benjamin Bynoe and Rowlett to visit Ribeira Grande and St Domingo. FitzRoy extended their stay to 23 days to complete his measurements of magnetism. Darwin subsequently wrote to Henslow that his collecting included "several specimens of an Octopus, which possessed a most marvellous power of changing its colours; equalling any chamaelion, & evidently accommodating the changes to the colour of the ground which it passed over.—yellowish green, dark brown & red were the prevailing colours: this fact appears to be new, as far as I can find out." Henslow replied that "The fact is not new, but any fresh observations will be highly important."

McCormick increasingly resented the favours FitzRoy gave to assist Darwin with collecting. On 16 February, FitzRoy landed a small party including himself and Darwin on St. Paul's Rocks, finding the seabirds so tame that they could be killed easily, while an exasperated McCormick was left circling the islets in a second small boat. That evening, novices were greeted by a pseudo- Neptune, and in the morning, they crossed the equator with the traditional line-crossing ceremony

The line-crossing ceremony is an initiation rite that commemorates a person's first crossing of the Equator. The tradition may have originated with ceremonies when passing headlands, and become a "folly" sanctioned as a boost to morale,Robert Fitz ...

.

Darwin had a special position as a guest and social equal of the captain, so junior officers called him "sir" until the captain dubbed Darwin ''Philos'' for "ship's philosopher", which became his suitably respectful nickname.

Surveying South America

In South America, ''Beagle'' carried out its survey work going to and fro along the coasts to allow careful measurement and rechecking. Darwin made long journeys inland with travelling companions from the locality. He spent much of the time away from the ship, returning by prearrangement when ''Beagle'' returned to ports where mail and newspapers were received, and Darwin's notes, journals, and collections sent back to England, via the Admiralty Packet Service. He had ensured that his collections were his own and, as prearranged, batches of his specimens were shipped to England, then taken by land carriage to Henslow inCambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

to await his return. The first batch was sent in August 1832, journey time varied considerably but all batches were eventually delivered.

Several others on board, including FitzRoy and other officers, were able amateur naturalists, and they gave Darwin generous assistance as well as making collections for the Crown, which the Admiralty placed in the British Museum.

Tropical paradise and slavery

Due to heavy surf, they only stayed atFernando de Noronha

Fernando de Noronha () is an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, part of the State of Pernambuco, Brazil, and located off the Brazilian coast. It consists of 21 islands and islets, extending over an area of . Only the eponymous main island is in ...

for a day to make the required observations, then FitzRoy pressed on to Bahia de Todos Santos, Brazil, to rate the chronometers and take on water. They reached the continent and arrived at the port on 28 February. Darwin was thrilled at the magnificent sight of "the town of Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro) and the 5th-largest b ...

or St Salvador", with large ships at harbour scattered across the bay. On the next day, he was in "transports of pleasure" walking by himself in the tropical forest, and in "long naturalizing walks" with others continued to "add raptures to the former raptures".

He found the sights of slavery offensive, and when FitzRoy defended the practice by describing a visit to a slaveowner whose slaves replied "no" on being asked by their master if they wished to be freed, Darwin suggested that answers in such circumstances were worthless. Enraged that his word had been questioned, FitzRoy lost his temper and banned Darwin from his company. The officers had nicknamed such outbursts "hot coffee", and within hours FitzRoy apologised, and asked Darwin to remain. Later, FitzRoy had to remain silent when Captain Paget visited them and recounted "facts about slavery so revolting" that refuted his claim.

Surveying of sandbanks around the harbour was completed on 18 March, and the ship made its way down the coast to survey the extent and depths of the Abrolhos reefs, completing and correcting Roussin's survey.

They manoeuvred ''Beagle'' into Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

harbour "in first rate style" on 4 April, with Darwin enthusiastically helping. Amidst excitement at opening letters from home, he was taken aback by news that his close friend Fanny Owen was engaged to marry Biddulph of Chirk Castle

Chirk Castle ( cy, Castell y Waun) is a Grade I listed castle located in Chirk, Wrexham County Borough, Wales.

History

The castle was built in 1295 by Roger Mortimer de Chirk, uncle of Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March as part of King Ed ...

. Augustus Earle

Augustus Earle (1793–1838) was a British painter. Unlike earlier artists who worked outside Europe and were employed on voyages of exploration or worked abroad for wealthy, often aristocratic patrons, Earle was able to operate quite indepen ...

showed Darwin round the town, and they found a delightful cottage for lodgings at Botafogo

Botafogo (local/standard alternative Brazilian Portuguese pronunciation: ) is a beachfront neighborhood ('' bairro'') in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It is a mostly upper middle class and small commerce community, and is located between the hills of ...

. Darwin made arrangements with local estate owners, and on 8 April set off with them on a strenuous "riding excursion" to Rio Macaè.

McCormick had made himself disagreeable to FitzRoy and first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

Wickham, so was "invalided home", as he also was on other voyages. In his 1884 memoirs, he claimed he had been "very much disappointed in my expectations of carrying out my natural history pursuits, every obstacle having been placed in the way of my getting on shore and making collections". Assistant Surgeon Benjamin Bynoe was made acting surgeon in his place.

The required observations from Villegagnon Island

Villegagnon Island (former Serigipe Island—original Portuguese: ''Ilha de Villegagnon''—also known in English as: Villegaignon Island, Island of Villegagnon or Island of Villegaignon) is located near the mouth of the large Guanabara Bay, in th ...

at Rio showed a discrepancy of of longitude in the meridian distance from Bahia to Rio, compared to Roussin's results, and FitzRoy wrote telling Beaufort he would go back to check.

On 24 April Darwin got back to the ship, next day his books, papers, and equipment suffered minor damage when the boat taking him to Botafogo cottage was swamped. He sent his sister his " commonplace Journal" to date, inviting criticisms, and decided to stay in the cottage with Earle while the ship went to Bahia.

Eight of the crew had gone snipe

A snipe is any of about 26 wading bird species in three genera in the family Scolopacidae. They are characterized by a very long, slender bill, eyes placed high on the head, and cryptic/ camouflaging plumage. The ''Gallinago'' snipes have a ...

shooting in the cutter, with an overnight stay at the Macacu River

The Macacu River ( pt, Rio Macacu) is a river of Rio de Janeiro state in southeastern Brazil.

Course

The Macacu River is born in the Serra dos Órgãos at about in the municipality of Cachoeiras de Macacu, and runs for about to its junction wi ...

near Rio. After their return on 2 May, some fell ill with fever. The ship set off on 10 May, a seaman died en route, a ship's boy

''Cabin Boy'' is a 1994 American fantasy comedy film, directed by Adam Resnick and co-produced by Tim Burton, which starred comedian Chris Elliott. Elliott co-wrote the film with Resnick. Both Elliott and Resnick worked for '' Late Night with Dav ...

and a young midshipman died at Bahia. The ship returned to Rio on 3 June. Having confirmed that his measurements were correct, FitzRoy sent corrections to Roussin.

At the cottage, Darwin composed his first letter outlining his collecting to Henslow. He said he would not "send a box till we arrive at Monte Video.—it is too great a loss of time both for Carpenters & myself to pack up whilst in harbor". He returned to the ship on 26 June, and they set sail on 5 July.

Amidst political changes, ''Beagle'' had a diplomatic role. As they arrived at Montevideo on 26 July, HMS ''Druid'' signalled them to "clear for action" as British property had been seized in growing unrest after "military usurpation" deposed Lavalleja

Lavalleja () is a department of Uruguay. Its capital is Minas. It is located in the southeast of the country, bordered to the north by the department of Treinta y Tres to the east with Rocha, to the south with Canelones and Maldonado, and to ...

. They took observations for the chronometers, then on 31 July sailed to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

to meet the governor and get maps, but were met by warning shots from a guard ship. FitzRoy promptly lodged a complaint and departed, threatening a broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

in response to any further provocation. When they got back on 4 August, FitzRoy informed the ''Druid''s captain who set off to demand an apology. On 5 August, Town officials and the British Consul asked FitzRoy for help to quell a mutiny; the garrison was held by Black troops loyal to Lavalleja. With Darwin and 50 well-armed men from the ship he arrived at the fort, then next day withdrew leaving a stand-off. Darwin enjoyed the excitement, and wrote "It was something new to me to walk with Pistols & Cutlass through the streets of a Town". ''Druid'' returned on 15 August, with a long apology from the government and news that the guard-ship captain had been arrested.

Darwin's first box of specimens was ready, and went on the Falmouth packet ''Emulous'' departing on 19 August, Henslow received the box in mid January.

On 22 August, after taking soundings in Samborombón Bay

Samborombón Bay () is a bay on the coast of Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Located at the Río de la Plata's mouth on the Argentine Sea, it begins about southeast of Buenos Aires and is about wide.

Toponymy

The bay is thought to have been ...

, ''Beagle'' began survey work down the coast from Cape San Antonio, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina.

Fossil finds

At Bahía Blanca, in the southern part of present Buenos Aires Province, Darwin rode inland intoPatagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and g ...

with gaucho

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and the south of Chilean Patagonia. Gauchos became greatly admired and ...

s: he saw them use bolas

Bolas or bolases (singular bola; from Spanish and Portuguese ''bola'', "ball", also known as a ''boleadora'' or ''boleadeira'') is a type of throwing weapon made of weights on the ends of interconnected cords, used to capture animals by entan ...

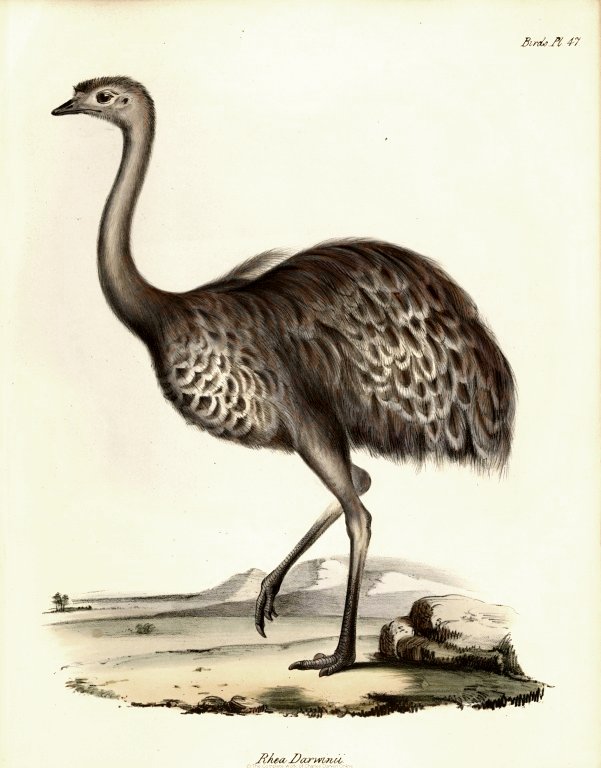

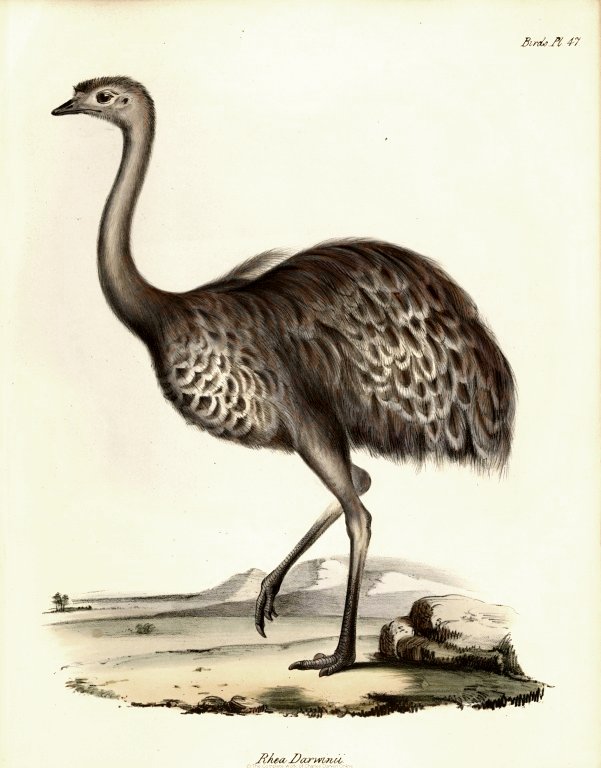

to bring down "ostriches" (rheas

The rheas ( ), also known as ñandus ( ) or South American ostriches, are large ratites (flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bone) in the order Rheiformes, native to South America, distantly related to the ostrich and emu. Most tax ...

) and ate roast armadillo. With FitzRoy, he went for "a very pleasant cruize about the bay" on 22 September, and about from the ship, they stopped for a while at Punta Alta

Punta Alta is a city in Argentina, about 20 kilometers southeast of Bahía Blanca. It has a population of 57,293. It is the capital ("cabecera") of the Coronel Rosales Partido. It was founded on 2 July 1898.

The city is located near the Atlant ...

. In low cliffs near the point, Darwin found conglomerate rocks containing numerous shells and fossilised teeth and bones of gigantic extinct mammals, in strata near an earth layer with shells and armadillo fossils, suggesting to him quiet tidal deposits rather than a catastrophe.'Cinnamon and port wine': an introduction to the ''Rio Notebook''Bahía Blanca, September—October 1832. With assistance (possibly from the young sailor Syms Covington acting as his servant), Darwin collected numerous fossils over several days, amusing others with "the cargoes of apparent rubbish which he frequently brought on board". Much of the second day was taken up with excavating a large skull which Darwin found embedded in soft rock, and seemed to him to be allied to the

rhinoceros

A rhinoceros (; ; ), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct species ...

. On 8 October, he returned to the site and found a jawbone and tooth which he was able to identify using Bory de Saint-Vincent's ''Dictionnaire classique''. He wrote home describing this and the large skull as ''Megatherium

''Megatherium'' ( ; from Greek () 'great' + () 'beast') is an extinct genus of ground sloths endemic to South America that lived from the Early Pliocene through the end of the Pleistocene. It is best known for the elephant-sized type species ' ...

'' fossils, or perhaps ''Megalonyx

''Megalonyx'' (Greek, "large claw") is an extinct genus of ground sloths of the family Megalonychidae, native to North America during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. It became extinct during the Quaternary extinction event at the end of th ...

'', and excitedly noted that the only specimens in Europe were locked away in the King's collection at Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

. In the same layer he found a large surface of polygonal plates of bony armour. His immediate thought was that they came from an enormous armadillo like the small creatures common in the area. However, from Cuvier's misleading description of the Madrid specimen and a recent newspaper report about a fossil collected by Woodbine Parish, Darwin thought that the bony armour identified the fossil as ''Megatherium''. With FitzRoy, Darwin went about across the bay to Monte Hermoso

Monte Hermoso is a town located on the Atlantic coast of Argentina, some east of the city of Bahía Blanca, in the south of the Province of Buenos Aires. It is the administrative seat of the partido of Monte Hermoso.

Founded at the beginning ...

on 19 October and found numerous fossils of smaller rodents in contrast to the huge Edentatal mammals of Punta Alta.

They returned to Montevideo, and on 2 November revisited Buenos Aires, passing the guard-ship which now gave them due respect. From questioning the finder of the ''Megatherium'' reported in the newspaper (Woodbine Parish’s agent), Darwin concluded it came from the same geological formation

A geological formation, or simply formation, is a body of rock having a consistent set of physical characteristics ( lithology) that distinguishes it from adjacent bodies of rock, and which occupies a particular position in the layers of rock exp ...

as his own fossil finds. He also "purchased fragments of some enormous bones" which he "was assured belonged to the former giants!!" In Montevideo from 14 November, he packaged his specimens, including all the fossils, and sent this cargo on the ''Duke of York'' Falmouth packet

Packet Newspapers (Cornwall) Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Newsquest media group, which publishes the ''Packet'' series of weekly tabloid newspapers.

The series is named after the Falmouth Packet service, which commenced operati ...

.

The mail from home included a copy of the second volume of Charles Lyell's ''Principles of Geology'', a refutation of Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

in which there was no shared ancestry of different species or overall progress to match the gradual geological change. Instead, it was a continuing cycle in which species mysteriously appeared, closely adapted to their "centres of creation", then became extinct when the environment changed to their disadvantage.

Tierra del Fuego

They reached

They reached Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

on 18 December 1832, and Darwin was taken by surprise at what he perceived as the crude savagery of the Yaghan natives, in stark contrast to the "civilised" behaviour of the three Fuegians they were returning as missionaries (who had been given the names York Minster, Fuegia Basket and Jemmy Button

Orundellico, known as "Jeremy Button" or "Jemmy Button" (c. 1815–1864), was a member of the Yaghan (or Yámana) people from islands around Tierra del Fuego, in modern Chile and Argentina. He was taken to England by Captain FitzRoy in HMS ''B ...

). He described his first meeting with the native Fuegians as being "without exception the most curious and interesting spectacle I ever beheld: I could not have believed how wide was the difference between savage and civilised man: it is greater than between a wild and domesticated animal, inasmuch as in man there is a greater power of improvement." They appeared like "the representations of Devils on the Stage" as in ''Der Freischütz

' ( J. 277, Op. 77 ''The Marksman'' or ''The Freeshooter'') is a German opera with spoken dialogue in three acts by Carl Maria von Weber with a libretto by Friedrich Kind, based on a story by Johann August Apel and Friedrich Laun from their 18 ...

''. In contrast, he said of Jemmy that "It seems yet wonderful to me, when I think over all his many good qualities, that he should have been of the same race, and doubtless partaken of the same character, with the miserable, degraded savages whom we first met here." (Four decades later, he recalled these impressions in ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biol ...

'' to support his argument that just as humans had descended from "a lower form", civilised society had arisen by graduations from a more primitive state. He recalled how closely the Fuegians on board ''Beagle'' "resembled us in disposition and in most of our mental faculties.")

At the island of "Buttons Land" on 23 January 1833, they set up a mission post with huts, gardens, furniture and crockery. Upon returning nine days later, the possessions had been looted and divided up equally by the natives. Matthews gave up, rejoining the ship and leaving the three civilised Fuegians to continue the missionary work. ''Beagle'' went on to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

, arriving just after the British return. Darwin studied the relationships of species to habitats and found ancient fossils like those he found in Wales. FitzRoy bought a schooner to assist with the surveying, and they returned to Patagonia, where it was fitted with a new copper bottom and renamed ''Adventure''. Syms Covington assisted Darwin in preserving specimens, and his collecting was so successful that, with FitzRoy's agreement, he hired Covington as a full-time servant for £30 a year.

Gauchos, rheas, fossils and geology

The two ships sailed to the Río Negro in Argentina, and on 8 August 1833, Darwin left on another journey inland with thegaucho

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and the south of Chilean Patagonia. Gauchos became greatly admired and ...

s. On 12 August, he met General Juan Manuel de Rosas who was then leading a punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beh ...

in his military campaign against native "Indians" and obtained a passport from him. As they crossed the pampas

The Pampas (from the qu, pampa, meaning "plain") are fertile South American low grasslands that cover more than and include the Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, and Córdoba; all of Uruguay; and Brazi ...

, the gauchos and Indians told Darwin of a rare smaller species of rhea. After three days at Bahía Blanca, he grew tired of waiting for ''Beagle,'' and on 21 August, revisited Punta Alta where he reviewed the geology of the site in light of his new knowledge, wondering if the bones were older than the seashells. He was very successful with searching for bones, and on 1 September, found a near-complete skeleton with its bones still in position.

He set off again and on 1 October, while searching the cliffs of the Carcarañá River, found "an enormous gnawing tooth", and then, in a cliff of the Paraná River, saw "two great groups of immense bones" which were too soft to collect but a tooth fragment identified them as mastodon

A mastodon ( 'breast' + 'tooth') is any proboscidean belonging to the extinct genus ''Mammut'' (family Mammutidae). Mastodons inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of th ...

s. Illness delayed him at Santa Fe, and after seeing the fossilised casing of a huge armadillo embedded in rock, he was puzzled to find a horse tooth in the same rock layer since horses had been introduced to the continent with European migration. They took a riverboat down the Paraná River to Buenos Aires