Sürgünlik on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The deportation of the Crimean Tatars (,

The

The  After the 1917

After the 1917

Cyrillic

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Ea ...

: Къырымтатар халкъынынъ сюргюнлиги) or the ('exile') was the ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

and the cultural genocide

Cultural genocide or culturicide is a concept first described by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944, in the same book that coined the term ''genocide''. The destruction of culture was a central component in Lemkin's formulation of genocide ...

of at least 191,044 Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

that was carried out by Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

authorities from 18 to 20 May 1944, supervised by Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria ka, ლავრენტი პავლეს ძე ბერია} ''Lavrenti Pavles dze Beria'' ( – 23 December 1953) was a Soviet politician and one of the longest-serving and most influential of Joseph ...

, chief of Soviet state security and the secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

, and ordered by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

. Within those three days, the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

used cattle trains to deport the Crimean Tatars, even Soviet Communist Party members and Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

soldiers, from Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

to the Uzbek SSR

The Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (, ), also known as Soviet Uzbekistan, the Uzbek SSR, UzSSR, or simply Uzbekistan and rarely Uzbekia, was a union republic of the Soviet Union. It was governed by the Uzbek branch of the Soviet Communist P ...

, several thousand kilometres away. They were one of several ethnicities

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, rel ...

that were subjected to Stalin's policy of population transfer in the Soviet Union

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forcibly transferred populations of various groups. These actions may be classif ...

.

Officially, the Soviet government presented the deportation as a policy of collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group or whole community for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member or some members of that group or area, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends a ...

, based on its claim that some Crimean Tatars collaborated with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

in World War II, despite the fact that the 20,000 who collaborated with the Axis powers were half the 40,000 who served in the Soviet Red Army. Several modern scholars believe rather that the government deported them as a part of its plan to gain access to the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

and acquire territory in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, where the Turkic ethnic kin of the Tatars lived, or remove minorities from the Soviet Union's border regions. By the end of the deportation, not a single Crimean Tatar lived in Crimea, and 80,000 houses and 360,000 acres of land were left abandoned. Nearly 8,000 Crimean Tatars died during the deportation, and tens of thousands subsequently perished due to the harsh living conditions in which they were forced to live during their exile. After the deportation, the Soviet government launched an intense detatarization campaign in an attempt to erase the remaining traces of Crimean Tatar existence.

In 1956, the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

condemned Stalin's policies, including the deportation of various ethnic groups, and he allowed most of these ethnic groups to return to their homelands, but he did not lift the directive that forbade the Crimean Tatars from returning. The Crimean Tatars remained in Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

for the next three decades, until the perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

era of the late 1980s, when 260,000 of them returned to Crimea, after 45 years in exile. On 14 November 1989, the Supreme Council of the Soviet Union declared that the deportations had been a crime, and declared that the ban on their return to Crimea was officially null and void.

By 2004, the number of Crimean Tatars who had returned to Crimea had increased their share of the peninsula's population to 12 percent. The Soviet government had not assisted them during their return to Crimea nor had it compensated them for the land they lost in the deportation. The deportation and the subsequent assimilation efforts in Asia are crucial events in the history of the Crimean Tatars. Between 2015 and 2024, the deportation was formally recognised as a genocide by Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Canada, Poland, Estonia and the Czech Republic.

Background

Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

controlled the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

from 1441 to 1783, when Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

was annexed by the Russian Empire as a target of Russian expansion. By the 14th century, most of the Turkic-speaking population of Crimea had adopted Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, following the conversion of Ozbeg Khan of the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as ''Ulug Ulus'' ( in Turkic) was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of ...

. It was the longest surviving state of the Golden Horde. They often engaged in conflicts with Moscow—from 1468 until the 17th century, Crimean Tatars fought several wars with the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

. Thus, after the establishment of the Russian rule, Crimean Tatars began leaving Crimea in several waves of emigration. Between 1784 and 1790, out of a total population of about a million, around 300,000 Crimean Tatars left for the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

The Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

triggered another mass exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

of Crimean Tatars. Between 1855 and 1866 at least 500,000 Muslims, and possibly up to 900,000, left the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

and emigrated to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Out of that number, at least one third were from Crimea, while the rest were from the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

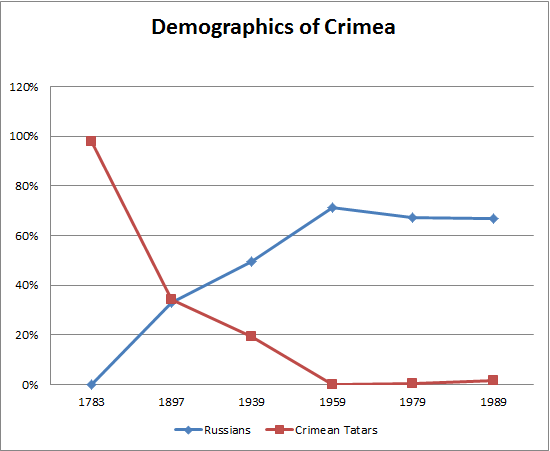

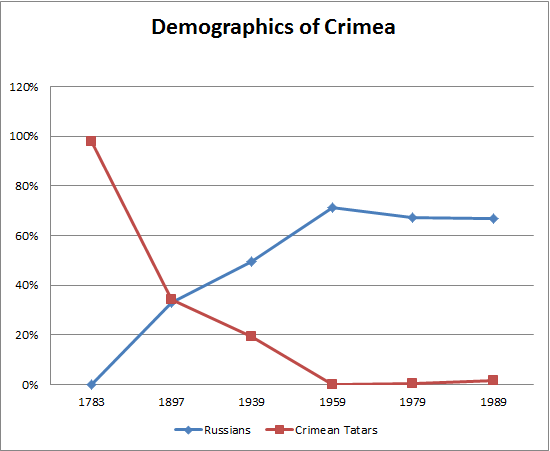

. These emigrants comprised 15–23 percent of the total population of Crimea. The Russian Empire used that fact as the ideological foundation to further Russify " New Russia". Eventually, the Crimean Tatars became a minority in Crimea; in 1783, they comprised 98 per cent of the population, but by 1897, this was down to 34.1 per cent. While Crimean Tatars were emigrating, the Russian government encouraged Russification

Russification (), Russianisation or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians adopt Russian culture and Russian language either voluntarily or as a result of a deliberate state policy.

Russification was at times ...

of the peninsula, populating it with Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

, Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

, and other Slavic

Slavic, Slav or Slavonic may refer to:

Peoples

* Slavic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group living in Europe and Asia

** East Slavic peoples, eastern group of Slavic peoples

** South Slavic peoples, southern group of Slavic peoples

** West Slav ...

ethnic groups; this Russification continued during the Soviet era. Vardys (1971), p. 101

After the 1917

After the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, Crimea received autonomous status inside the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

on 18 October 1921, but collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

in the 1920s led to severe famine from which up to 100,000 Crimeans perished when their crops were transported to "more important" regions of the Soviet Union. By one estimate, three-quarters of the famine victims were Crimean Tatars. Their status deteriorated further after Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

became the ''de facto'' Soviet leader and implemented repressions that led to the deaths of at least 5.2 million Soviet citizens between 1927 and 1938.

World War II

In 1940, theCrimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

Several different governments controlled the Crimean Peninsula during the period of the Soviet Union, from the 1920s to 1991. The government of Crimea from 1921 to 1936 was the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, which was an Autonomo ...

had approximately 1,126,800 inhabitants, of which 218,000 people, or 19.4 percent of the population, were Crimean Tatars. In 1941, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

invaded Eastern Europe, annexing much of the western USSR. Crimean Tatars initially viewed the Germans as liberators from Stalinism, and they had also been positively treated by the Germans in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Williams (2015), p. 92

Many of the captured Crimean Tatars serving in the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

were sent to POW camps after Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

and Nazis came to occupy the bulk of Crimea. Though Nazis initially called for murder of all "Asiatic inferiors" and paraded around Crimean Tatar POW's labeled as "Mongol sub-humanity", they revised this policy in the face of determined resistance from the Red Army. Beginning in 1942, Germans recruited Soviet prisoners of war to form support armies. The Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; or ''Dobrudža''; , or ; ; Dobrujan Tatar: ''Tomrîğa''; Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and ) is a Geography, geographical and historical region in Southeastern Europe that has been divided since the 19th century betw ...

n Tatar nationalist Fazil Ulkusal and Lipka Tatar

The Lipka Tatars are a Turkic ethnic group and minority in Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus who originally settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the beginning of the 14th century.

The first Tatar settlers tried to preserve their Pagan tradi ...

Edige Kirimal helped in freeing Crimean Tatars from German prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured as Prisoner of war, prisoners of war by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, inte ...

s and enlisting them in the independent Crimean support legion for the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

''. This legion eventually included eight battalions, although many members were of other nationalities. From November 1941, German authorities allowed Crimean Tatars to establish Muslim Committees in various towns as a symbolic recognition of some local government authority, though they were not given any political power.

Many Crimean Tatar communists strongly opposed the occupation and assisted the resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

to provide valuable strategic and political information. Other Crimean Tatars also fought on the side of the Soviet partisans, like the Tarhanov movement of 250 Crimean Tatars which fought throughout 1942 until its destruction. Six Crimean Tatars were even named the Heroes of the Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union () was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded together with the Order of Lenin personally or collectively for heroic feats in service to the Soviet state and society. The title was awarded both t ...

, and thousands more were awarded high honors in the Red Army.

Up to 130,000 people died during the Axis occupation of Crimea. The Nazis implemented a brutal repression, destroying more than 70 villages that were together home to about 25 per cent of the Crimean Tatar population. Thousands of Crimean Tatars were forcibly transferred to work as ''Ostarbeiter

' (, "Eastern worker") was a Nazi German designation for foreign slave workers gathered from occupied Central and Eastern Europe to perform forced labor in Germany during World War II. The Germans started deporting civilians at the beginning ...

'' in German factories under the supervision of the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

in what were described as "vast slave workshops", resulting in loss of all Crimean Tatar support. In April 1944 the Red Army managed to repel the Axis forces

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

from the peninsula in the Crimean Offensive.

A majority of the hiwis (helpers), their families and all those associated with the Muslim Committees were evacuated to Germany and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

or Dobruja by the Wehrmacht and Romanian Army where they joined the Eastern Turkic division. Thus, the majority of the collaborators had been evacuated from Crimea by the retreating Wehrmacht. Many Soviet officials had also recognized this and rejected claims that the Crimean Tatars had betrayed the Soviet Union ''en masse''. The presence of Muslim Committees organized from Berlin by various Turkic foreigners appeared a cause for concern in the eyes of the Soviet government, already wary of Turkey at the time.

Falsification of information in propaganda

Soviet publications blatantly falsified information about Crimean Tatars in the Red Army, going so far as to describe Crimean TatarHero of the Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union () was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded together with the Order of Lenin personally or collectively for heroic feats in service to the Soviet state and society. The title was awarded both ...

Uzeir Abduramanov as Azeri Azeri or Azeri Turk may refer to:

* Azeri people, an ethnic group also known as Azerbaijanis

* Citizens of Azerbaijan

* Azeri language, the modern-day Turkic language

* Old Azeri, an extinct Iranian language

* Azeri Turk (journal), Academic jour ...

, not Crimean Tatar, on the cover of a 1944 issue of ''Ogonyok'' magazine – even though his family had been deported for being Crimean Tatar just a few months earlier. The book ''In the Mountains of Tavria'' falsely claimed that volunteer partisan scout Bekir Osmanov was a German spy and shot, although the central committee later acknowledged that he never served the Germans and survived the war, ordering later editions to have corrections after still-living Osmanov and his family noticed the obvious falsehood. Amet-khan Sultan, born to a Crimean Tatar mother and Lak father in Crimea, where he was born and raised, was often described as a Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; ; ), officially the Republic of Dagestan, is a republic of Russia situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, along the Caspian Sea. It is located north of the Greater Caucasus, and is a part of the North Caucasian Fede ...

i in post-deportation media, even though he always considered himself a Crimean Tatar.

The partisan movement in Crimea, spearheaded by A. V. Mokrousov, ultimately proved to be unsuccessful, primarily due to Mokrousov's inebriation and military ineptitude. In an attempt to rationalize their military shortcomings, the leadership of the partisan movement propagated allegations against the Crimean Tatars, claiming that they had largely defected to the German forces. This narrative served as a pretext for Soviet partisans

Soviet partisans were members of Resistance during World War II, resistance movements that fought a Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla war against Axis powers, Axis forces during World War II in the Soviet Union, the previously Territories of Poland an ...

to conduct raids on Crimean Tatar villages in search of provisions. During these incursions, partisans engaged in indiscriminate violence against civilians and appropriated food supplies, thereby exacerbating the plight of those who survived and leaving them vulnerable to starvation.

In response to these circumstances, the German authorities sanctioned the establishment of Crimean Tatar ''Schuma'' battalions, tasked with defending their communities against such raids. It is noteworthy that the Crimean Tatars exhibited a form of military collaboration; they either actively resisted the Red Army or defended their villages from partisan attacks. This stands in contrast to the actions of the Russians in Crimea, who were implicated in the repression of civilians and participated in the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

. The Russian historian I. A. Makhalova, an expert on collaborationism during World War II, has commented on these dynamics:

In addition, Crimean Tatar victims of Nazi atrocities are widely ignored and even erased from the historical memory. For example, at the site of the December 1941 Nazi massacre in Simferopol, where both Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, Krymchaks

Krymchaks ( Krymchak: , , , ) are Jewish ethno-religious communities of Crimea derived from Turkic-speaking adherents of Rabbinic Judaism.Romani Crimean Tatars were exterminated by the Nazis, the monument to the victims of the massacre mentions only Jews and Krymchaks but completely omits any mention of the Romani Crimean Tatars who were killed in the exact same spot. Years after the Nazi massacre of Crimean Tatars in the village of Burlak-Toma who were accused of being "tatar-gypsies", the government refused to acknowledge that the victims were Crimean Tatars, despite strong protests from witnesses and surviving family members of the victims, who consistently gave sworn testimony that they were indeed Crimean Tatars.

Nikolai Bugay and his disciples, including A. M. Gonov, A. S. Khunagov, and others, have endeavored to provide a justification for the deportation of various ethnic groups within the USSR. In light of the inability to rely on discredited accusations that were repudiated by the KGB during the Perestroika period in the 1980s, these scholars resort to employing omissions, ambiguous insinuations, and conclusions that lack logical coherence with their initial premises. Furthermore, there are instances of document falsification that undermine the credibility of their arguments.

Officially due to the

Officially due to the  On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete. However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units had forgotten to deport people from the

On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete. However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units had forgotten to deport people from the  In total, 151,136 Crimean Tatars were deported to the Uzbek SSR; 8,597 to the

In total, 151,136 Crimean Tatars were deported to the Uzbek SSR; 8,597 to the

In March 2014, the

In March 2014, the

Despite the thousands of Crimean Tatars in the Red Army when it attacked Berlin, the Crimean Tatars continued to be seen and treated as a fifth column for decades. Some historians explain this as part of Stalin's plan to take complete control of Crimea. The Soviet sought access to the

Despite the thousands of Crimean Tatars in the Red Army when it attacked Berlin, the Crimean Tatars continued to be seen and treated as a fifth column for decades. Some historians explain this as part of Stalin's plan to take complete control of Crimea. The Soviet sought access to the

File:Геноцид кримських татар 10 срібло реверс.jpg, Ukrainian coin commemorating the Genocide of the Crimean Tatars, issued 2015

File:The projection mapping on the Ukrainian Government Building for the Day of Remembrance for the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide.webm, The

In 2008, Lily Hyde, a British journalist living in Ukraine, published a novel titled ''Dreamland'' that revolves around a Crimean Tatar family return to their homeland in the 1990s. The story is told from the perspective of a 12-year-old girl who moves from Uzbekistan to a demolished village with her parents, brother, and grandfather. Her grandfather tells her stories about the heroes and victims among the Crimean Tatars.

The 2013 Ukrainian Crimean Tatar-language film '' Haytarma'' portrays the experience of Crimean Tatar flying ace and

In 2008, Lily Hyde, a British journalist living in Ukraine, published a novel titled ''Dreamland'' that revolves around a Crimean Tatar family return to their homeland in the 1990s. The story is told from the perspective of a 12-year-old girl who moves from Uzbekistan to a demolished village with her parents, brother, and grandfather. Her grandfather tells her stories about the heroes and victims among the Crimean Tatars.

The 2013 Ukrainian Crimean Tatar-language film '' Haytarma'' portrays the experience of Crimean Tatar flying ace and

Deportation

Officially due to the

Officially due to the collaboration

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. The ...

with the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the Soviet government collectively punished ten ethnic minorities, among them the Crimean Tatars. Punishment included deportation to distant regions of Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. Soviet accounts of the late 1940s indict the Crimean Tatars collectively as an ethnicity of traitors. Although the Crimean Tatars denied that they had committed universal treason, this idea persisted during the Soviet period and Russian scholarly and popular literature.

According to various estimates, around 20,000 Crimean Tatars volunteered to fight for Nazi Germany, as opposed to 40,000 who fought for the Red Army. On 10 May 1944, Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria ka, ლავრენტი პავლეს ძე ბერია} ''Lavrenti Pavles dze Beria'' ( – 23 December 1953) was a Soviet politician and one of the longest-serving and most influential of Joseph ...

recommended to Stalin that the Crimean Tatars should be deported away from the border regions due to their "traitorous actions". Stalin subsequently issued GKO Order No. 5859ss, which envisaged the resettlement of the Crimean Tatars. Buckley, Ruble & Hoffman (2008), p. 231 The deportation lasted only three days, 18–20 May 1944, during which NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

agents went house to house collecting Crimean Tatars at gunpoint and forcing them to enter sealed-off cattle trains that would transfer them almost to remote locations in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic

The Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (, ), also known as Soviet Uzbekistan, the Uzbek SSR, UzSSR, or simply Uzbekistan and rarely Uzbekia, was a Republics of the Soviet Union, union republic of the Soviet Union. It was governed by the Communist ...

. The Crimean Tatars were allowed to carry up to of their property per family. The only ones who could avoid this fate were Crimean Tatar women who were married to men of non-punished ethnic groups. The exiled Crimean Tatars travelled in overcrowded wagons for several weeks and lacked food and water. It is estimated that at least 228,392 people were deported from Crimea, of which at least 191,044 were Crimean Tatars in 47,000 families. Since 7,889 people perished in the long transit in sealed-off railcars, the NKVD registered the 183,155 living Crimean Tatars who arrived at their destinations in Central Asia. The majority of the deportees were rounded up from the Crimean countryside. Only 18,983 of the exiles were from Crimean cities.

On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete. However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units had forgotten to deport people from the

On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete. However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units had forgotten to deport people from the Arabat Spit

The Arabat Spit (; ; ) or Arabat Arrow is a spit (landform), barrier spit that separates the large, shallow, salty Syvash lagoons from the Sea of Azov. The spit runs between the Henichesk Strait in the north and the north-eastern shores of Crim ...

. Instead of preparing an additional transfer in trains, on 20 July the NKVD boarded hundreds of Crimean Tatars onto an old boat, took it to the middle of the Azov Sea

The Sea of Azov is an inland shelf sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, and sometimes regarded as a northern extension of the Black Sea. The sea is bounded by Russia on the east, and by Ukr ...

, and sank the ship. Those who did not drown were finished off by machine guns.

Officially, Crimean Tatars were eliminated from Crimea. The deportation encompassed every person considered by the government to be Crimean Tatar, including children, women, and the elderly, and even those who had been members of the Communist Party or the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

. As such, they were legally designated as special settler

Special settlements in the Soviet Union were the result of population transfers and were performed in a series of operations organized according to social class or nationality of the deported. Resettling of "enemy classes" such as prosperous ...

s, which meant that they were officially second-class citizens, prohibited from leaving the perimeter of their assigned area, attending prestigious universities, and had to regularly appear before the commandant's office.

During this mass eviction, the Soviet authorities confiscated around 80,000 houses, 500,000 cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are calle ...

, 360,000 acres

The acre ( ) is a unit of land area used in the British imperial and the United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, ...

of land, and 40,000 tons of agricultural provisions. Besides 191,000 deported Crimean Tatars, the Soviet authorities also evicted 9,620 Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

, 12,420 Bulgarians

Bulgarians (, ) are a nation and South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and its neighbouring region, who share a common Bulgarian ancestry, culture, history and language. They form the majority of the population in Bulgaria, ...

, and 15,040 Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

from the peninsula. All were collectively branded as traitors and became second-class citizens for decades in the USSR. 1,119 Germans and 3,652 foreign citizens were also expelled. Among the deported, there were also 283 persons of other ethnicities: Italians

Italians (, ) are a European peoples, European ethnic group native to the Italian geographical region. Italians share a common Italian culture, culture, History of Italy, history, Cultural heritage, ancestry and Italian language, language. ...

, Romanians, Karaims, Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

, Czechs

The Czechs (, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common Bohemia ...

, Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars, are an Ethnicity, ethnic group native to Hungary (), who share a common Culture of Hungary, culture, Hungarian language, language and History of Hungary, history. They also have a notable presence in former pa ...

, and Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

. During 1947 and 1948, a further 2,012 veteran returnees were deported from Crimea by the local MVD

The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation (MVD; , ''Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del'') is the interior ministry of Russia.

The MVD is responsible for law enforcement in Russia through its agencies the Police of Russia, Migration ...

.

Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

The Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Mari ASSR) ( Mari: Марий Автоном Совет Социализм Республик, ''Mariy Avtonom Sovet Sotsializm Respublik'') was an autonomous republic of the Russian SFSR, succeeding ...

; and 4,286 to the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic

The Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, also known as Soviet Kazakhstan, the Kazakh SSR, KSSR, or simply Kazakhstan, was one of the transcontinental country, transcontinental Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Un ...

; and the remaining 29,846 were sent to various remote regions of the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

. When the Crimean Tatars arrived at their destination in the Uzbek SSR, they were met with hostility by Uzbek locals who threw stones at them, even their children, because they heard that the Crimean Tatars were "traitors" and "fascist collaborators." The Uzbeks objected to becoming the "dumping ground for treasonous nations." In the coming years, several assaults against the Crimean Tatars population were registered, some of which were fatal.

The mass Crimean deportations were organized by Lavrentiy Beria, the chief of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, and his subordinates Bogdan Kobulov

Bogdan Zakharovich Kobulov (; 1 March 1904 – 23 December 1953) served as a senior member of the Soviet security- and police-apparatus during the rule of Joseph Stalin. After Stalin's death he was arrested and executed along with his former chie ...

, Ivan Serov

Ivan Alexandrovich Serov (; 13 August 1905 – 1 July 1990) was a Soviet intelligence officer who served as Chairman of the KGB from March 1954 to December 1958 and Director of the GRU from December 1958 to February 1963. Serov was NKVD Commis ...

, B. P. Obruchnikov, M.G. Svinelupov, and A. N. Apolonov. The field operations were conducted by G. P. Dobrynin, the Deputy Head of the Gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

system; G. A. Bezhanov, the Colonel of State Security; I. I. Piiashev, Major General; S. A. Klepov, Commissar of State Security; I. S. Sheredega, Lt. General; B. I. Tekayev, Lt. Colonel of State Security; and two local leaders, P. M. Fokin, head of the Crimea NKGB, and V. T. Sergjenko, Lt. General. In order to execute this deportation, the NKVD secured 5,000 armed agents and the NKGB

The People's Commissariat for State Security () or NKGB, was the name of the Soviet secret police, intelligence and counter-intelligence force that existed from 3 February 1941 to 20 July 1941, and again from 1943 to 1946, before being rename ...

allocated a further 20,000 armed men, together with a few thousand regular soldiers. Two of Stalin's directives from May 1944 reveal that many parts of the Soviet government, from financing to transit, were involved in executing the operation.

On 14 July 1944 the GKO authorized the migration of 51,000 people, mostly Russians, to 17,000 empty collective farms on Crimea. On 30 June 1945, the Crimean ASSR was abolished.

Soviet propaganda

Propaganda in the Soviet Union was the practice of state-directed communication aimed at promoting class conflict, proletarian internationalism, the goals of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the party itself.

The main Soviet cen ...

sought to hide the population transfer by claiming that the Crimean Tatars had "voluntarily resettle to Central Asia". In essence, though, according to historian Paul Robert Magocsi

Paul Robert Magocsi (; born January 26, 1945) is an American professor of history, political science, and Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto. He has been with the university since 1980 and became a Fellow of the Royal Societ ...

, Crimea was " ethnically cleansed." After this act, the term ''Crimean Tatar'' was banished from the Russian-Soviet lexicon, and all Crimean Tatar toponyms

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for a proper nam ...

(names of towns, villages, and mountains) in Crimea were changed to Russian names on all maps as part of a wide detatarization campaign. Muslim graveyards and religious objects in Crimea were demolished or converted into secular places. During Stalin's rule, nobody was allowed to mention that this ethnicity even existed in the USSR. This went so far that many individuals were even forbidden to declare themselves as Crimean Tatars during the Soviet censuses of 1959, 1970

Events

January

* January 1 – Unix time epoch reached at 00:00:00 UTC.

* January 5 – The 7.1 1970 Tonghai earthquake, Tonghai earthquake shakes Tonghai County, Yunnan province, China, with a maximum Mercalli intensity scale, Mercalli ...

, and 1979. They could only declare themselves as Tatars. This ban was lifted during the Soviet census of 1989.

Aftermath

Mortality and death toll

The first deportees started arriving in the Uzbek SSR on 29 May 1944 and most had arrived by 8 June 1944. The consequentmortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular Statistical population, population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically ...

remains disputed; the NKVD kept incomplete records of the death rate among the resettled ethnicities living in exile. Like the other deported peoples, the Crimean Tatars were placed under the regime of special settlements. Many of those deported performed forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

: their tasks included working in coal mines

Coal mining is the process of resource extraction, extracting coal from the ground or from a mine. Coal is valued for its Energy value of coal, energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to Electricity generation, generate electr ...

and construction battalions, under the supervision of the NKVD. Deserters were executed. Special settlers routinely worked eleven to twelve hours a day, seven days a week. Despite this difficult physical labor, the Crimean Tatars were given only around to of bread per day. Accommodations were insufficient; some were forced to live in mud hut

A hut is a small dwelling, which may be constructed of various local materials. Huts are a type of vernacular architecture because they are built of readily available materials such as wood, snow, stone, grass, palm leaves, branches, clay, hid ...

s where "there were no doors or windows, nothing, just reeds" on the floor to sleep on.

The sole transport to these remote areas and labour colonies was equally as strenuous. Theoretically, the NKVD loaded 50 people into each railroad car, together with their property. One witness claimed that 133 people were in her wagon. They had only one hole in the floor of the wagon which was used as a toilet. Some pregnant women were forced to give birth inside these sealed-off railroad cars. The conditions in the overcrowded train wagons were exacerbated by a lack of hygiene

Hygiene is a set of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

, leading to cases of typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

. Since the trains only stopped to open the doors at rare occasions during the trip, the sick inevitably contaminated others in the wagons. It was only when they arrived at their destination in the Uzbek SSR that the Crimean Tatars were released from the sealed-off railroad cars. Still, some were redirected to other destinations in Central Asia and had to continue their journey. Some witnesses claimed that they travelled for 24 consecutive days. During this whole time, they were given very little food or water while trapped inside. There was no fresh air since the doors and windows were bolted shut. In Kazakh SSR

The Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, also known as Soviet Kazakhstan, the Kazakh SSR, KSSR, or simply Kazakhstan, was one of the transcontinental constituent republics of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1936 to 1991. Located in northern Centr ...

, the transport guards unlocked the door only to toss out the corpses along the railroad. The Crimean Tatars thus called these railcars "crematoria

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a corpse through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and Syria, cremation on an open-air pyr ...

on wheels." The records show that at least 7,889 Crimean Tatars died during this long journey, amounting to about 4 per cent of their entire ethnicity.

The high mortality rate continued for several years in exile due to malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

, labor exploitation

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

, diseases, lack of medical care, and exposure to the harsh desert climate of Uzbekistan. The exiles were frequently assigned to the heaviest construction sites. The Uzbek medical facilities filled with Crimean Tatars who were susceptible to the local Asian diseases not found on the Crimean peninsula where the water was purer, including yellow fever, dystrophy

Dystrophy is the degeneration of tissue, due to disease or malnutrition, most likely due to heredity.

Types

* Muscular dystrophy

** Duchenne muscular dystrophy

** Becker's muscular dystrophy

** Myotonic dystrophy

* Reflex neurovascular dy ...

, malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, and intestinal illness. The death toll was the highest during the first five years. In 1949 the Soviet authorities counted the population of the deported ethnic groups who lived in special settlements. According to their records, there were 44,887 excess death

In epidemiology, the excess deaths or excess mortality is a measure of the increase in the number of deaths during a time period and/or in a certain group, as compared to the expected value or statistical trend during a reference period (typicall ...

s in these five years, 19.6 per cent of that total group. Buckley, Ruble & Hofmann (2008), p. 207 Other sources give a figure of 44,125 deaths during that time, while a third source, using alternative NKVD archives, gives a figure of 32,107 deaths. These reports included all the people resettled from Crimea (including Armenians, Bulgarians, and Greeks), but the Crimean Tatars formed a majority in this group. It took five years until the number of births among the deported people started to surpass the number of deaths. Soviet archives reveal that between May 1944 and January 1945 a total of 13,592 Crimean Tatars perished in exile, about 7 per cent of their entire population. Almost half of all deaths (6,096) were of children under the age of 16; another 4,525 were adult women and 2,562 were adult men. During 1945, a further 13,183 people died. Thus, by the end of December 1945, at least 27,000 Crimean Tatars had already died in exile. One Crimean Tatar woman living near Tashkent recalled the events from 1944:

Estimates produced by Crimean Tatars indicate mortality figures that were far higher and amounted to 46% of their population living in exile. In 1968, when Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

presided over the USSR, Crimean Tatar activists were persecuted for using that high mortality figure under the guise that it was a "slander to the USSR." In order to show that Crimean Tatars were exaggerating, the KGB published figures showing that "only" 22 per cent of that ethnic group died. The Karachay demographer Dalchat Ediev estimates that 34,300 Crimean Tatars died due to the deportation, representing an 18 per cent mortality rate. Hannibal Travis estimates that overall 40,000–80,000 Crimean Tatars died in exile. Professor Michael Rywkin gives a figure of at least 42,000 Crimean Tatars who died between 1944 and 1951, including 7,900 who died during the transit Professor Brian Glyn Williams

Brian Glyn Williams is a professor of Islamic History at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth who worked for the CIA. As an undergraduate, he attended Stetson University, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in 1988. He received his PhD in Mid ...

gives a figure of between 40,000 and 44,000 deaths as a consequence of this deportation. The Crimean State Committee estimated that 45,000 Crimean Tatars died between 1944 and 1948. The official NKVD report estimated that 27 per cent of that ethnicity died.

Various estimates of the mortality rates of the Crimean Tatars:

Rehabilitation

Stalin's government denied the Crimean Tatars the right to education orpublication

To publish is to make content available to the general public.Berne Convention, articl ...

in their native language. Despite the prohibition, and although they had to study in Russian or Uzbek, they maintained their cultural identity. In 1956 the new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, held a speech in which he condemned Stalin's policies, including the mass deportations of various ethnicities. Still, even though many peoples were allowed to return to their homes, three groups were forced to stay in exile: the Soviet Germans, the Meskhetian Turks

Meskhetian Turks, also referred to as Turkish Meskhetians, Ahiska Turks, and Turkish Ahiskans, (; ka, მესხეთის თურქები ''Meskhetis turk'ebi'') are a subgroup of ethnic Turkish people formerly inhabiting the Mes ...

, and the Crimean Tatars. In 1954, Khrushchev allowed Crimea to be included in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

since Crimea is linked by land to Ukraine and not with the Russian SFSR. On 28 April 1956, the directive "On Removing Restrictions on the Special Settlement of the Crimean Tatars... Relocated during the Great Patriotic War" was issued, ordering a de-registration of the deportees and their release from administrative supervision. However, various other restrictions were still kept and the Crimean Tatars were not allowed to return to Crimea. Moreover, that same year the Ukrainian Council of Ministers banned the exiled Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Germans, Armenians and Bulgarians from relocating even to the Kherson

Kherson (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and , , ) is a port city in southern Ukraine that serves as the administrative centre of Kherson Oblast. Located by the Black Sea and on the Dnieper, Dnieper River, Kherson is the home to a major ship-bui ...

, Zaporizhzhia

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. It is the Capital city, administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia ...

, Mykolaiv

Mykolaiv ( ), also known as Nikolaev ( ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and a hromada (municipality) in southern Ukraine. Mykolaiv is the Administrative centre, administrative center of Mykolaiv Raion (Raions of Ukraine, district) and Myk ...

and Odesa Oblast

Odesa Oblast (), also referred to as Odeshchyna (Одещина), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) of southwestern Ukraine, located along the northern coast of the Black Sea. Its administrative centre is the city of Ode ...

s in the Ukrainian SSR. The Crimean Tatars did not get any compensation for their lost property.

In the 1950s, the Crimean Tatars started actively advocating for the right to return. In 1957, they collected 6,000 signatures in a petition that was sent to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union

The Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (SSUSSR) was the highest body of state authority of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1936 to 1991. Based on the principle of unified power, it was the only branch of government in the So ...

that demanded their political rehabilitation

Political rehabilitation is the process by which a disgraced member of a political party or a government is restored to public respectability and thus political acceptability. The term is usually applied to leaders or other prominent individuals ...

and return to Crimea. In 1961 25,000 signatures were collected in a petition that was sent to the Kremlin

The Moscow Kremlin (also the Kremlin) is a fortified complex in Moscow, Russia. Located in the centre of the country's capital city, the Moscow Kremlin (fortification), Kremlin comprises five palaces, four cathedrals, and the enclosing Mosco ...

.

Mustafa Dzhemilev

Mustafa Abduldzhemil Jemilev (, ), also known widely with his adopted descriptive surname Qırımoğlu "Son of Crimea" ( Crimean Tatar Cyrillic: , ; born 13 November 1943, Ay Serez, Crimea), is the former chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean T ...

, who was only six months old when his family was deported from Crimea, grew up in Uzbekistan and became an activist for the right of the Crimean Tatars to return. In 1966 he was arrested for the first time and spent a total of 17 years in prison during the Soviet era. This earned him the nickname of "Crimean Tatar Mandela." In 1984 he was sentenced for the sixth time for "anti-Soviet activity" but was given moral support by the Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov (; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet Physics, physicist and a List of Nobel Peace Prize laureates, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, which he was awarded in 1975 for emphasizing human rights around the world.

Alt ...

, who had observed Dzhemilev's fourth trial in 1976. When older dissidents were arrested, a new, younger generation emerged that would replace them.

On 21 July 1967, representatives of the Crimean Tatars, led by the dissident Ayshe Seitmuratova, gained permission to meet with high-ranking Soviet officials in Moscow, including Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov ( – 9 February 1984) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from late 1982 until his death in 1984. He previously served as the List of Chairmen of t ...

. During the meeting, the Crimean Tatars demanded a correction of all the injustices of the USSR against their people. In September 1967, the Supreme Soviet issued a decree that acknowledged the charge of treason against the entire nation was "unreasonable" but that did not allow Crimean Tatars the same full rehabilitation encompassing the right of return that other deported peoples were given. The carefully worded decree referred to them not as "Crimean Tatars" but as "citizens of Tatar nationality who having formerly lived in Crimea ��have taken root in the Uzbek SSR", thereby minimizing Crimean Tatar existence and downplaying their desire for the right of return in addition to creating a premise for claims of the issue being "settled". Individuals united and formed groups that went back to Crimea in 1968 on their own, without state permission, but the Soviet authorities deported 6,000 of them once again. The most notable example of such resistance was a Crimean Tatar activist, Musa Mamut, who was deported when he was 12 and who returned to Crimea because he wanted to see his home again. When the police informed him that he would be evicted, he set himself on fire. Nevertheless, 577 families managed to obtain state permission to reside in Crimea.

In 1968 unrest erupted among the Crimean Tatar people in the Uzbek city of Chirchiq

Chirchiq, also spelled as Chirchik, (; ) is a district-level city in Tashkent Region, Uzbekistan. It is about 32 km northeast of Tashkent, along the river Chirchiq. Chirchiq lies in the Chatkal Mountains. The population of Chirchiq as of 20 ...

. In October 1973, the Jewish poet and professor Ilya Gabay committed suicide by jumping off a building in Moscow. He was one of the significant Jewish dissidents in the USSR who fought for the rights of the oppressed peoples, especially Crimean Tatars. Gabay had been arrested and sent to a labour camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see British and American spelling differences, spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are unfree labour, forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have ...

but still insisted on his cause because he was convinced that the treatment of the Crimean Tatars by the USSR amounted to genocide. In 1973, Dzhemilev was also arrested for his advocacy for Crimean Tatar right to return to Crimea.

Repatriation

Despitede-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

, the situation did not change until Gorbachev's perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

in the late 1980s. A 1987 Tatar protest near the Kremlin

The Moscow Kremlin (also the Kremlin) is a fortified complex in Moscow, Russia. Located in the centre of the country's capital city, the Moscow Kremlin (fortification), Kremlin comprises five palaces, four cathedrals, and the enclosing Mosco ...

prompted Gorbachev to form the Gromyko Commission which found against Tatar claims, but a second commission recommended "renewal of autonomy" for Crimean Tatars. In 1989 the ban on the return of deported ethnicities was declared officially null and void and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union

The Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (SSUSSR) was the highest body of state authority of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1936 to 1991. Based on the principle of unified power, it was the only branch of government in the So ...

further declared the deportations criminal, paving the way for the Crimean Tatars to return. Dzhemilev returned to Crimea that year, with at least 166,000 other Tatars doing the same by January 1992. The 1991 Russian law ''On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples

''On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples'' () is the law N 1107-I of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic signed on April 29, 1991 and updated by the July 1, 1993 law N 5303-I of the Russian Federation.

The law was preceded by th ...

'' rehabilitated all Soviet repressed ethnicities and abolished all previous Russian laws relating to the deportations, calling for the "restoration and return of the cultural and spiritual values and archives which represent the heritage of the repressed people."

By 2004 the Crimean Tatars formed 12 per cent of the population of Crimea. The return was fraught: with Russian nationalist

Russian nationalism () is a form of nationalism that promotes Russian cultural identity and unity. Russian nationalism first rose to prominence as a Pan-Slavic enterprise during the 19th century Russian Empire, and was repressed during the early ...

protests in Crimea and clashes between locals and Crimean Tatars near Yalta

Yalta (: ) is a resort town, resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crime ...

, which needed army intervention. Local Soviet authorities were reluctant to help returnees with jobs or housing, After the dissolution of the USSR

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Dissolution'', a 2002 novel by Richard Lee Byers in the War of the Spider Queen series

* Dissolution (Sansom novel), ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), by C. J. Sansom, 2003

* Dissolution (Binge no ...

, Crimea was part of Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, but Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

gave limited support to Crimean Tatar settlers. Some 150,000 of the returnees were granted citizenship automatically under Ukraine's Citizenship Law

Nationality law is the law of a sovereign state, and of each of its jurisdictions, that defines the legal manner in which a national identity is acquired and how it may be lost. In international law, the legal means to acquire nationality and for ...

of 1991, but 100,000 who returned after Ukraine declared independence faced several obstacles including a costly bureaucratic process.

Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

In March 2014, the

In March 2014, the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

In February and March 2014, Russia invaded the Crimea, Crimean Peninsula, part of Ukraine, and then annexed it. This took place in the relative power vacuum immediately following the Revolution of Dignity. It marked the beginning of the Russ ...

unfolded, which was, in turn, declared illegal by the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

(United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262 was adopted on 27 March 2014 by the sixty-eighth session of the United Nations General Assembly in response to the Russian annexation of Crimea and entitled "Territorial integrity of Ukraine ...

) and which led to further deterioration of the rights of the Crimean Tatars. Even though the Russian Federation

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

issued Decree No. 268 "On the Measures for the Rehabilitation of Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, Crimean Tatar and German Peoples and the State Support of Their Revival and Development" on 21 April 2014, in practice Russia has intensified persecution of Crimean Tatars and their human rights situation has significantly deteriorated. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is a department of the United Nations Secretariat that works to promote and protect human rights that are guaranteed under international law and stipulated in the Univers ...

issued a warning against the Kremlin in 2016 because it "intimidated, harassed and jailed Crimean Tatar representatives, often on dubious charges", while the representative body the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People

The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People () is the single highest executive-representative body of the Crimean Tatars in period between sessions of the Qurultay of the Crimean Tatar People. The Mejlis is a member institution of the Platform of E ...

was banned.

The UN reported that of the over 10,000 people left Crimea after the annexation in 2014, most were Crimean Tatars, which caused a further decline of their fragile community. Crimean Tatars stated several reasons for their departure, among them insecurity, fear, and intimidation from the new Russian authorities. In its 2015 report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that various human rights violations

Human rights are universally recognized moral principles or norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both national and international laws. These rights are considered inherent and inalienable, meaning t ...

were recorded in Crimea, including the prevention of Crimean Tatars from marking the 71st anniversary of their deportation.

Modern views and legacy

Historian Edward Allworth has noted that the extent of marginalization of the Crimean Tatars was a distinct anomaly among national policy in the USSR given the party's firm commitment maintaining the status quo of not recognizing them as a distinct ethnic group in addition to assimilating and "rooting" them in exile, in sharp contrast to the rehabilitation other deported ethnic groups such as the Chechens, Ingush, Karachays, Balkars, and Kalmyks experienced in the Khrushchev era. Between 1989 and 1994, around a quarter of a million Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea from exile in Central Asia. This was seen as a symbolic victory of their efforts to return to their native land. They returned after 45 years of exile. Not one of the several ethnic groups who were deported during Stalin's era received any kind of financial compensation. Some Crimean Tatar groups and activists have called for the international community to put pressure on the Russian Federation, thesuccessor state

Succession of states is a concept in international relations regarding a successor state that has become a sovereign state over a territory (and populace) that was previously under the sovereignty of another state. The theory has its roots in 19th ...

of the USSR, to finance rehabilitation of that ethnicity and provide financial compensation

Financial compensation refers to the act of providing a person with money or other things of economic value in exchange for their goods, labor, or to provide for the costs of injuries that they have incurred. The aim of financial compensation ...

for forcible resettlement.

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

and control of territory in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, where the Crimean Tatars had ethnic kin. By painting the Crimean Tatars as traitors, this taint could be extended to their kin. Scholar Walter Kolarz alleges that the deportation and the attempt of liquidation of Crimean Tatars as an ethnicity in 1944 was just the final act of the centuries-long process of Russian colonization of Crimea that started in 1783. Historian Gregory Dufaud regards the Soviet accusations against Crimean Tatars as a convenient excuse for their forcible transfer through which Moscow secured an unrivalled access to the geostrategic southern Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

on one hand and eliminated hypothetical rebellious nations at the same time. Professor of Russian and Soviet history Rebecca Manley similarly concluded that the real aim of the Soviet government was to "cleanse" the border regions of "unreliable elements". Professor Brian Glyn Williams

Brian Glyn Williams is a professor of Islamic History at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth who worked for the CIA. As an undergraduate, he attended Stetson University, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in 1988. He received his PhD in Mid ...

states that the deportations of Meskhetian Turks

Meskhetian Turks, also referred to as Turkish Meskhetians, Ahiska Turks, and Turkish Ahiskans, (; ka, მესხეთის თურქები ''Meskhetis turk'ebi'') are a subgroup of ethnic Turkish people formerly inhabiting the Mes ...

, despite never being close to the scene of combat and never being charged with any crime, lends the strongest credence to the fact that the deportations of Crimeans and Caucasians was due to Soviet foreign policy rather than any real "universal mass crimes".

Modern interpretations by scholars and historians sometimes classify this mass deportation of civilians as a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

, ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

, depopulation

Population decline, also known as depopulation, is a reduction in a human population size. Throughout history, Earth's total human population has continued to grow but projections suggest this long-term trend may be coming to an end.

From ant ...

, an act of Stalinist repression, or an "ethnocide

Ethnocide is the extermination or destruction of ethnic identities. Bartolomé Clavero differentiates ethnocide from genocide by stating that "Genocide kills people while ethnocide kills social cultures through the killing of individual souls". ...

", meaning a deliberate wiping out of an identity and culture of a nation. Crimean Tatars call this event ''Sürgünlik'' ("exile"). The perception of Crimean Tatars as "uncivilized" and deserving the deportation remains throughout the Russian and Ukrainian settlers in Crimea.

Genocide question and recognition

Some activists, politicians, scholars, countries, and historians go even further and consider the deportation a crime ofgenocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

or cultural genocide

Cultural genocide or culturicide is a concept first described by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944, in the same book that coined the term ''genocide''. The destruction of culture was a central component in Lemkin's formulation of genocide ...

. Norman Naimark

Norman M. Naimark (; born 1944, New York City) is an American historian. He is the Robert and Florence McDonnell Professor of Eastern European Studies at Stanford University, and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. He writes on modern Ea ...

writes " e Chechens and Ingush, the Crimean Tatars, and other 'punished peoples' of the wartime period were, indeed, slated for elimination, if not physically, then as self-identifying nationalities." Professor Lyman H. Legters argued that the Soviet penal system, combined with its resettlement policies, should count as genocidal since the sentences were borne most heavily specifically on certain ethnic groups, and that a relocation of these ethnic groups, whose survival depends on ties to its particular homeland, "had a genocidal effect remediable only by restoration of the group to its homeland." Political scientist Stephen Blank described it both as a deportation and a genocide, a centuries-long Russian "technique of self-colonial rule intended to eliminate" minorities. Soviet dissidents Ilya Gabay and Pyotr Grigorenko

Petro Grigorenko or Petro Hryhorovych Hryhorenko (, – 21 February 1987) was a high-ranking Soviet Army commander of Ukrainians, Ukrainian descent, who in his fifties became a dissident