Surrender At Discretion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees, reassurances, or promises (i.e., conditions) are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

Announcing that only unconditional surrender is acceptable puts psychological pressure on a weaker adversary, but it may also prolong hostilities. A party typically only demands unconditional surrender when it has a significant advantage over their adversaries, when victory is thought to be inevitable.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most often include guarantees provided by

The use of the term was revived during

The use of the term was revived during

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen A. A. K. Niazi, CO of Pakistan Armed Forces located in

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen A. A. K. Niazi, CO of Pakistan Armed Forces located in

Judgement: The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity

contained in the

German Surrender Documents of WWII

(US Historical Documents) {{DEFAULTSORT:Unconditional Surrender Surrenders Military strategy

international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

. In some cases, surrender is truly accepted unconditionally; while in other cases terms are offered and accepted, but forces are declared to be subject to "unconditional surrender" for symbolic purposes. This type of surrender may also be accepted by the surrendering party under the expectation of guarantees agreed to informally.

Examples

Banu Qurayza during Muhammad's era

After the Battle of the Trench, in which the Muslims tactically overcame their opponents while suffering very few casualties, efforts to defeat the Muslims failed, andIslam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

became influential in the region. As a consequence, the Muslim army besieged the neighbourhood of the Banu Qurayza tribe, leading to their unconditional surrender.Watt, ''Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman'', pp. 167–174. All the men, apart from a few who converted to Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, were executed, while the women and children were enslaved.Peterson, ''Muhammad: the prophet of God'', pp. 125–127.Ramadan, ''In the Footsteps of the Prophet'', pp. 140f.Hodgson, ''The Venture of Islam'', vol. 1, p. 191.Brown, ''A New Introduction to Islam'', p. 81.Lings, ''Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources'', pp. 229–233. The historicity of the incident has been questioned. For details and references see discussion

Conversation is interactive communication between two or more people. The development of conversational skills and etiquette is an important part of socialization. The development of conversational skills in a new language is a frequent focus ...

in main article

Main may refer to:

Geography

*Main River (disambiguation), multiple rivers with the same name

*Ma'in, an ancient kingdom in modern-day Yemen

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*Spanish Main, the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territ ...

.

Napoleon Bonaparte

WhenNapoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

escaped from his enforced exile on the island of Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

, one of the steps that the delegates of the European powers at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

took was to issue a statement on 13 March 1815 declaring Napoleon Bonaparte to be an outlaw. The text includes the following paragraphs:

Consequently, as Napoleon was considered an outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them. ...

when he surrendered to Captain Maitland of at the end of the Hundred Days

The Hundred Days ( ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition (), marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII o ...

, he was not protected by military law or international law as a head of state and so the British were under no legal obligation to either accept his surrender or to spare his life. However, they did so to prevent him from being a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

and exiled him to the remote South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

island of Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

.

American Civil War

The most famous early use of the phrase in theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

occurred during the 1862 Battle of Fort Donelson

The Battle of Fort Donelson was fought from February 11–16, 1862, in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. The Union capture of the Confederate fort near the Tennessee–Kentucky border opened the Cumberland River, an important ave ...

. Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

of the Union Army received a request for terms from Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner Sr., the fort's commanding officer. Grant's reply was that "no terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." When news of Grant's victory, one of the Union's first in the war, was received in Washington, DC

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

, newspapers remarked (and President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

endorsed) that Grant's first two initials, "U.S.," stood for "Unconditional Surrender," which would later become his nickname.

However, subsequent surrenders to Grant were not unconditional. When Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

at Appomattox Court House in 1865, Grant agreed to allow the men under Lee's command to go home under parole and to keep sidearms and private horses. Generous terms were also offered to John C. Pemberton at Vicksburg and, by Grant's subordinate, William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a General officer, general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), earning recognit ...

, to Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American military officer who served in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia declared secession from ...

in North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

.

Grant was not the first officer in the Civil War to use the phrase. The first instance came some days earlier, when Confederate Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman

Lloyd Tilghman (January 18, 1816 – May 16, 1863) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War.

A railroad construction engineer by background, he was selected by the Confederate government to build two forts to defend the Tennessee ...

asked for terms of surrender during the Battle of Fort Henry

The Battle of Fort Henry was fought on February 6, 1862, in Stewart County, Tennessee, during the American Civil War. It was the first important victory for the Union and Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Western Theater.

On February 4 an ...

. Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote replied, "no sir, your surrender will be unconditional." Even at Fort Donelson, earlier in the day, a Confederate messenger approached Brigadier General Charles Ferguson Smith, Grant's subordinate, for terms of surrender, and Smith stated, "I'll have no terms with Rebels with guns in their hands, my terms are unconditional and immediate surrender." The messenger was passed along to Grant, but there is no evidence that either Foote or Smith influenced Grant's choice of words.

In 1863, Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everts Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the American Civil War and a three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successfu ...

forced an unconditional surrender of the Cumberland Gap and 2,300 Confederate soldiers, and in 1864, Union General Gordon Granger

Gordon Granger (November 6, 1821 – January 10, 1876) was a career U.S. Army officer, and a Union (American Civil War), Union general during the American Civil War, where he distinguished himself at the Battle of Chickamauga.

Granger is best re ...

forced an unconditional surrender of Fort Morgan.

World War II

The use of the term was revived during

The use of the term was revived during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

at the Casablanca conference

The Casablanca Conference (codenamed SYMBOL) or Anfa Conference was held in Casablanca, French Morocco, from January 14 to 24, 1943, to plan the Allies of World War II, Allied European strategy for the next phase of World War II. The main disc ...

in January 1943 when American President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

stated it to the press as the objective of the war against the Axis Powers of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. When Roosevelt made the announcement at Casablanca, he referred to General Grant's use of the term during the American Civil War.

The term was also used in the Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, ...

issued to Japan on July 26, 1945. Near the end of the declaration, it said, "We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces" and warned that the alternative was "prompt and utter destruction."

It has been claimed that it prolonged the war in Europe by its usefulness to German domestic propaganda, which used it to encourage further resistance against the Allied armies, and by its suppressive effect on the German resistance movement since even after a coup against Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

:

It has also been argued that without the demand for unconditional surrender, Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

might not have fallen behind the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

. "It was a policy that the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

accepted with alacrity, probably because a completely destroyed Germany would facilitate Russia's postwar expansion program." It has also been claimed to have prolonged the war with Japan or to be a cause of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (see debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Substantial debate exists over the ethical, legal, and military aspects of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 August and 9 August 1945 respectively at the close of the Pacific War theater of World War II (1939–45), as well as t ...

).

One reason for the policy was that the Allies wished to avoid a repetition of the stab-in-the-back myth

The stab-in-the-back myth (, , ) was an antisemitic and anti-communist conspiracy theory that was widely believed and promulgated in Germany after 1918. It maintained that the Imperial German Army did not lose World War I on the battlefield, b ...

, which had arisen in Germany after World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and attributed Germany's loss to betrayal by Jews, Bolsheviks, and Socialists, as well as the fact that the war ended before the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

had reached Germany. The myth was used by the Nazis in their propaganda. An unconditional surrender was felt to ensure that the Germans knew that they had lost the war themselves.

Bangladesh War of Independence

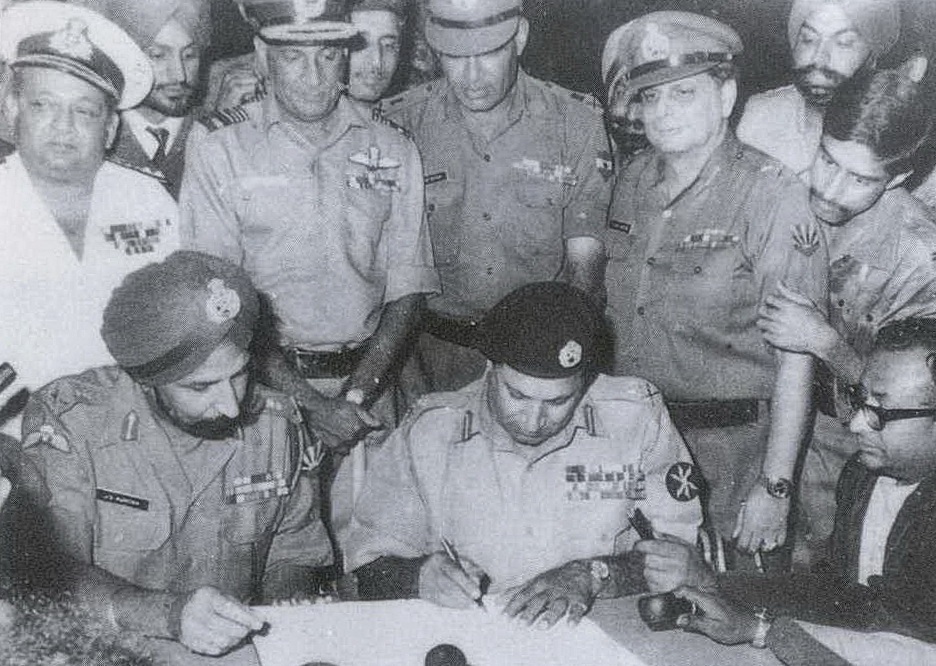

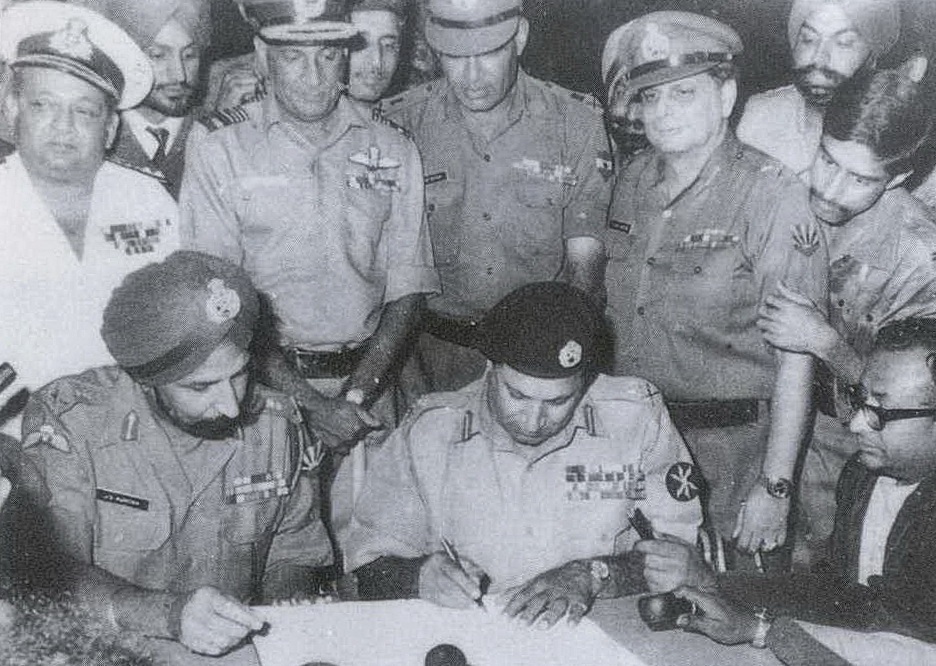

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen A. A. K. Niazi, CO of Pakistan Armed Forces located in

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen A. A. K. Niazi, CO of Pakistan Armed Forces located in East Pakistan

East Pakistan was the eastern province of Pakistan between 1955 and 1971, restructured and renamed from the province of East Bengal and covering the territory of the modern country of Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Burma, wit ...

(now Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

) signed the Instrument of Surrender handing over the command of his forces stationed in East Pakistan to the Indian Army under General Jagjit Singh Aurora. This led to the surrender of 93,000 personnel including families of the Pakistan's East Command and cessation of hostilities between the Pakistani Armed Forces and the Indian Armed Forces along with the guerrilla forces, the Mukti Bahini

The Mukti Bahini, initially called the Mukti Fauj, also known as the Bangladesh Forces, was a big tent armed guerrilla resistance movement consisting of the Bangladeshi military personnel, paramilitary personnel and civilians during the Ba ...

.

The signing of this unconditional surrender document gave Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, The original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are international humanitarian laws consisting of four treaties and three additional protocols that establish international legal standards for humanitarian t ...

guarantees for the safety of the surrendered soldiers and completed the independence of Bangladesh

The independence of Bangladesh was Proclamation of Bangladeshi Independence, declared from Pakistan on 26 March 1971, which is now celebrated as Independence Day (Bangladesh), Independence Day. The Bangladesh Liberation War started on 26 March ...

.

Afghanistan War

On 15 August 2021, the government of theIslamic Republic of Afghanistan

The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was a presidential republic in Afghanistan from 2004 to 2021. The state was established to replace the Afghan Afghan Interim Administration, interim (2001–2002) and Transitional Islamic State of Afghanist ...

and the Afghan National Security Forces

The Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), also known as the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF), were the military and internal security forces of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.

As of 30 June 2020, the ANSF was composed of ...

unconditionally surrendered to the Taliban

, leader1_title = Supreme Leader of Afghanistan, Supreme leaders

, leader1_name = {{indented plainlist,

* Mullah Omar{{Natural Causes{{nbsp(1994–2013)

* Akhtar Mansour{{Assassinated (2015–2016)

* Hibatullah Akhundzada (2016–present) ...

. The unconditional surrender brought an end to the conflict and allowed the Taliban to take over Afghanistan and establish their government in the country.

Surrender at discretion

Insiege warfare

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characte ...

, the demand for the garrison to surrender unconditionally to the besiegers is traditionally phrased as "surrender at discretion." If there are negotiations with mutually agreed conditions, the garrison is said to have "surrendered on terms." One example was at the Siege of Stirling, during the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion:

Surrender at discretion was also used at the Battle of the Alamo

The Battle of the Alamo (February 23 – March 6, 1836) was a pivotal event and military engagement in the Texas Revolution. Following a siege of the Alamo, 13-day siege, Mexico, Mexican troops under president of Mexico, President Antonio L� ...

, when Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. often known as Santa Anna, wa ...

asked Jim Bowie

James Bowie ( ) (April 10, 1796 – March 6, 1836) was an American military officer, landowner and slave trader who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He was among the Americans who died at the Battle of the Alamo. Stories of him ...

and William B. Travis for unconditional surrender. Even though Bowie wished to surrender unconditionally, Travis refused, fired a cannon at Santa Anna's army, and wrote in his final dispatches:

The phrase surrender at discretion is still used in treaties. For example, the Rome Statute

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome, Italy on 17 July 1998Michael P. Scharf (August 1998)''Results of the R ...

, in force since July 1, 2002, specifies under "Article 8 war crimes, Paragraph 2.b:"

The wording in the Rome Statute is taken almost word for word from Article 23 of the 1907 IV Hague Convention ''The Laws and Customs of War on Land'': "...it is especially forbidden – ... To kill or wound an enemy who, having laid down his arms, or having no longer means of defence, has surrendered at discretion", and it is part of the customary laws of war

The law of war is a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of hostilities (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, ...

.The Nuremberg War Trial judgment on ''The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity'' held, "The rules of land warfare expressed in the ague Convention of 1907undoubtedly represented an advance over existing international law at the time of their adoption. But the Convention expressly stated that it was an attempt 'to revise the general laws and customs of war,' which it thus recognised to be then existing, but by 1939 these rules laid down in the Convention were recognised by all civilised nations, and were regarded as being declaratory of the laws and customs of war....",Judgement: The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity

contained in the

Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the b ...

archive at Yale Law School

Yale Law School (YLS) is the law school of Yale University, a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was established in 1824. The 2020–21 acceptance rate was 4%, the lowest of any law school in the United ...

).

See also

*Surrender (military)

Surrender, in military terms, is the relinquishment of control over territory, combatants, fortifications, ships or armament to another power. A surrender may be accomplished peacefully or it may be the result of defeat in battle. A sovereign ...

*Debellatio

The term or "debellation" (Latin 'defeating, or the act of conquering or subduing', literally, 'warring (the enemy) down', from Latin 'war') designates the end of war caused by complete destruction of a hostile state. Israeli law-school professo ...

designates the end of a war caused by complete destruction of a hostile state.

*Military occupation

Military occupation, also called belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is temporary hostile control exerted by a ruling power's military apparatus over a sovereign territory that is outside of the legal boundaries of that ruling pow ...

*Giving no quarter

No quarter, during War, military conflict or piracy, implies that combatants would not be taken Prisoner of war, prisoner, but executed. Since the Hague Convention of 1899, it is considered a war crime; it is also prohibited in customary interna ...

, refusal by the victor to spare the lives of surrendered foes

*Suing for peace

Suing for peace is an act by a warring party to initiate a peace process.

Rationales

"Suing for", in this older sense of the phrase, means "pleading or petitioning for". Suing for peace is usually initiated by the losing party in an attempt to ...

References

External links

German Surrender Documents of WWII

(US Historical Documents) {{DEFAULTSORT:Unconditional Surrender Surrenders Military strategy