Statute Of Westminster, 1931 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that significantly increased the autonomy of the

Dominions did not possess full sovereignty on an equal footing with the United Kingdom. The

Dominions did not possess full sovereignty on an equal footing with the United Kingdom. The

Australia adopted sections 2 to 6 of the Statute of Westminster with the

Australia adopted sections 2 to 6 of the Statute of Westminster with the

9351 I.R. The Irish Free State, which in 1937 was renamed ''Ireland'', left the Commonwealth on 18 April 1949 upon the

The preamble to the Statute of Westminster sets out a guideline for changing the rules of succession to

The preamble to the Statute of Westminster sets out a guideline for changing the rules of succession to

During the

During the

online

* Mansergh, Nicholas. ''Survey of British Commonwealth affairs: problems of external policy, 1931–1939'' (Oxford University Press, 1952). * Nicolson, Harold. ''King George V'' (1953) pp 470–488

online

* Wheare, K. C. ''The Statute of Westminster, 1931'' (Clarendon Press, 1933). * Wheare, K. C. ''The Statute of Westminster and dominion status'' (Oxford University Press, 1953).

Digital reproduction of the Original Act on the Parliamentary Archives catalogue

Australia and the Statute of Westminster

{{DEFAULTSORT:Statute of Westminster 1931 Commonwealth realms 1931 in British law United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1931 Australian constitutional law History of the British Empire History of the Commonwealth of Nations History of Newfoundland and Labrador Political charters 1931 in international relations Sovereignty British constitutional laws concerning Ireland Australia–United Kingdom relations Canada–United Kingdom relations Ireland–United Kingdom relations New Zealand–United Kingdom relations South Africa–United Kingdom relations December 1931 Australia and the Commonwealth of Nations Canada and the Commonwealth of Nations Ireland and the Commonwealth of Nations New Zealand and the Commonwealth of Nations South Africa and the Commonwealth of Nations United Kingdom and the Commonwealth of Nations Constitution of Canada December 1931 in the United Kingdom

Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s of the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

.

Passed on 11 December 1931, the statute increased the sovereignty of the self-governing Dominions of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

from the United Kingdom. It also bound them all to seek each other's approval for changes to monarchical titles and the common line of succession. The statute was effective either immediately or upon ratification. It thus became a statutory embodiment of the principles of equality and common allegiance to the Crown set out in the Balfour Declaration of 1926

The Balfour Declaration of 1926 was issued by the 1926 Imperial Conference of British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent t ...

. As the statute removed nearly all of the British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

's authority to legislate for the Dominions, it was a crucial step in the development of the Dominions as separate, independent, and sovereign states.

Its modified versions are now domestic law in Australia and Canada; it has been repealed in New Zealand and implicitly in former Dominions that are no longer Commonwealth realms.

History

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, and Britain after 1707, had colonies outside of Europe since the late 16th century. These early colonies were largely run by private companies rather than the Crown directly, but by the end of the century had ( except for India) been subsumed under Crown control. Oversight of these colonies oscillated between relatively lax enforcement of laws and centralization of power depending on the politics of the day, but the Parliament in Westminster always remained supreme. Most colonies in North America broke away from British rule and became independent as the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in the late 18th century, where after British attention turned towards Australia and Asia.

British policy with regards to the colonies began to be rationalized and streamlined in the 19th century. Responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

, wherein colonial governments were held accountable to legislatures just as the British cabinet was responsible to the British Parliament, was granted to colonies beginning with Nova Scotia in 1848. Confusion existed as to what extent British legislation applied to the colonies; in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

, justice Benjamin Boothby caused a nuisance by striking down several local laws as contrary ("repugnant") to the legislation in Britain. Westminster rectified this situation by passing the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865, which allowed the colonies to pass legislation different from that in Britain provided that it was not repugnant to any law expressly passed by the Imperial Parliament to extend to that colony. This had the dual effect of granting colonies autonomy within their borders while subordinating them to the British Parliament otherwise.

Most of the remaining colonies in North Americaeverything north of the United States with the exception of Newfoundlandwere merged into a federal polity known as "Canada" in the late 1860s and early 1870s. Canada was termed a "dominion", a term previously used in slightly different contexts in English history, and granted a broad array of powers between the federal government and the provincial governments. Australia was similarly deemed a dominion when it federated in 1901, as were Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, and the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

in the first decades of the 20th century.

Dominions did not possess full sovereignty on an equal footing with the United Kingdom. The

Dominions did not possess full sovereignty on an equal footing with the United Kingdom. The parliament of Canada

The Parliament of Canada () is the Canadian federalism, federal legislature of Canada. The Monarchy of Canada, Crown, along with two chambers: the Senate of Canada, Senate and the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons, form the Bicameral ...

passed a law barring appeals from its Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

to the imperial Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 August ...

in 1888, but in 1925 a judgement of the Privy Council determined that this law was invalid. Combined with the King–Byng affair

The King–Byng affair, also known as the King–Byng Wing Ding, was a Canadian constitutional crisis that occurred in 1926, when the governor general of Canada, Lord Byng of Vimy, refused a request by the prime minister, William Lyon Mackenz ...

the following year, this bred resentment in Canada and led to its insistence on full sovereignty. The leadership of the Irish Free State, meanwhile, was dominated by those who had fought a war of independence

Wars of national liberation, also called wars of independence or wars of liberation, are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) ...

against Britain and who had agreed to dominion status as a compromise; they took a maximalist view of the autonomy they had secured in the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

and pushed for recognition of their state's sovereignty, which would have implications for the other dominions as well. The 1926 Imperial Conference

The 1926 Imperial Conference was the fifth Imperial Conference bringing together the prime ministers of the Dominions of the British Empire. It was held in London from 19 October to 23 November 1926. The conference was notable for producing the ...

led to the Balfour declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

that dominions were equal in status to one another and to the United Kingdom. Further conferences in 1929 and 1930 worked out a substantive framework to implement this declaration. This became the Statute of Westminster 1931.

Application

The Statute of Westminster gave effect to certain political resolutions passed by theImperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

s of 1926

In Turkey, the year technically contained only 352 days. As Friday, December 18, 1926 ''(Julian Calendar)'' was followed by Saturday, January 1, 1927 '' (Gregorian Calendar)''. 13 days were dropped to make the switch. Turkey thus became the ...

and 1930; in particular, the Balfour Declaration of 1926

The Balfour Declaration of 1926 was issued by the 1926 Imperial Conference of British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent t ...

. The main effect was the removal of the ability of the British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

to legislate for the Dominions, part of which also required the repeal of the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 in its application to the Dominions. King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

expressed his desire that the laws of royal succession be exempt from the statute's provisions, but it was determined that this would be contrary to the principles of equality set out in the Balfour Declaration. Both Canada and the Irish Free State pushed for the ability to amend the succession laws themselves and section 2(2) (allowing a Dominion to amend or repeal laws of paramount force, such as the succession laws, insofar as they are part of the law of that Dominion) was included in the Statute of Westminster at Canada's insistence. After the statute was passed, the British parliament could no longer make laws for the Dominions, other than with the request and consent of the government of that Dominion.

The statute provides in section 4:

It also provides in section 2(1):

The whole statute applied to the Dominion of Canada

While a variety of theories have been postulated for the name of Canada, its origin is now accepted as coming from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word , meaning 'village' or 'settlement'. In 1535, indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Quebec C ...

, the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, and the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

without the need for any acts of ratification; the governments of those countries gave their consent to the application of the law to their respective jurisdictions. Section 10 of the statute provided that sections 2 to 6 would apply in the other three Dominions —Australia, New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, and Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

– only after the respective parliament of that Dominion had legislated to adopt them.

Since 1931, over a dozen new Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations that has the same constitutional monarch and head of state as the other realms. The current monarch is King Charles III. Except for the United Kingdom, in each of the re ...

s have been created, all of which now hold the same powers as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand over matters of change to the monarchy, though the Statute of Westminster is not part of their laws. Ireland and South Africa are now republics and Newfoundland is now part of Canada as a province.

Australia

Australia adopted sections 2 to 6 of the Statute of Westminster with the

Australia adopted sections 2 to 6 of the Statute of Westminster with the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942

The Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 is an act of the Australian Parliament that formally adopted sections 2–6 of the Statute of Westminster 1931, an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom enabling the total legislative independ ...

, in order to clarify the validity of certain Australian legislation relating to the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

; the adoption was backdated to 3 September 1939, the date that Britain and Australia joined the war.

Adopting section 2 of the statute clarified that the Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Parliament of the Commonwealth and also known as the Federal Parliament) is the federal legislature of Australia. It consists of three elements: the Monarchy of Australia, monarch of Australia (repr ...

was able to legislate inconsistently with British legislation, adopting section 3 clarified that it could legislate with extraterritorial effect. Adopting section 4 clarified that Britain could legislate with effect on Australia as a whole only with Australia's request and consent.

Nonetheless, under section 9 of the statute, on matters not within Commonwealth power Britain could still legislate with effect in all or any of the Australian states, without the agreement of the Commonwealth although only to the extent of "the constitutional practice existing before the commencement" of the statute. However, this capacity had never been used. In particular, it was not used to implement the result of the 1933 Western Australian secession referendum, as it did not have the support of the Australian government.

All British power to legislate with effect in Australia ended with the Australia Act 1986

The ''Australia Act 1986'' is the short title of each of a pair of separate but related pieces of legislation: one an act of the Parliament of Australia, the other an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. In Australia they are refe ...

, the British version of which says that it was passed with the request and consent of the Australian Parliament, which had obtained the concurrence of the parliaments of the Australian states.

Canada

This statute limited the legislative authority of the British parliament over Canada, effectively giving the country legal autonomy as a self-governing Dominion, though the British parliament retained the power to amend Canada's constitution at the request of Canada. That authority remained in effect until theConstitution Act, 1982

The ''Constitution Act, 1982'' () is a part of the Constitution of Canada.Formally enacted as Schedule B of the '' Canada Act 1982'', enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Section 60 of the ''Constitution Act, 1982'' states that t ...

, which transferred it to Canada, the final step to achieving full sovereignty.

The British North America Acts—the written elements (in 1931) of the Canadian constitution—were excluded from the application of the statute because of disagreements between the Canadian provinces

Canada has ten provinces and three territories that are sub-national administrative divisions under the jurisdiction of the Canadian Constitution. In the 1867 Canadian Confederation, three provinces of British North America—New Brunswick, N ...

and the federal government over how the British North America Acts could be otherwise amended. These disagreements were resolved only in time for the passage of the Canada Act 1982

The Canada Act 1982 (1982 c. 11) () is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and one of the enactments which make up the Constitution of Canada. It was enacted at the request of the Senate and House of Commons of Canada to patriate ...

, thus completing the patriation

Patriation is the political process that led to full Canadian sovereignty, culminating with the '' Constitution Act, 1982''. The process was necessary because, at the time, under the '' Statute of Westminster, 1931'', and with Canada's agreemen ...

of the Canadian constitution to Canada.

At that time, the Parliament of the United Kingdom also repealed ss 4 and 7(1) of the Statute of Westminster as applied to Canada. The Statute of Westminster, as amended, remains a part of the constitution of Canada by virtue of section 52(2)(''b'') of and the schedule to the Constitution Act, 1982. The Newfoundland Terms of Union expressly provide for the application of the Statute of Westminster to the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.Newfoundland Act, Schedule, Term 48.

As a consequence of the statute's adoption, the Parliament of Canada

The Parliament of Canada () is the Canadian federalism, federal legislature of Canada. The Monarchy of Canada, Crown, along with two chambers: the Senate of Canada, Senate and the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons, form the Bicameral ...

gained the ability to abolish appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 August ...

. Criminal appeals were abolished in 1933, while civil appeals continued until 1949. The passage of the Statute of Westminster meant that changes in British legislation governing the succession to the throne no longer automatically applied to Canada.

Irish Free State

TheIrish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

never formally adopted the Statute of Westminster, its Executive Council (cabinet) taking the view that the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

of 1921 had already ended Westminster's right to legislate for the Irish Free State. The Free State's constitution gave the Oireachtas

The Oireachtas ( ; ), sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the Bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of the president of Ireland and the two houses of the Oireachtas (): a house ...

"sole and exclusive power of making laws". Hence, even before 1931, the Irish Free State did not arrest deserters

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or Military base, post without permission (a Pass (military), pass, Shore leave, liberty or Leave (U.S. military), leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with u ...

from the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

on its territory, even though the UK believed post-1922 British laws gave the Free State's Garda Síochána

(; meaning "the Guardian(s) of the Peace") is the national police and security service of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is more commonly referred to as the Gardaí (; "Guardians") or "the Guards". The service is headed by the Garda Commissio ...

the power to do so. The UK's Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922

The Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 (Session 2) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, passed in 1922 to enact in UK law the Constitution of the Irish Free State, and to ratify the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty formally.

Provisio ...

said, however, " in the ree StateConstitution shall be construed as prejudicing the power of he BritishParliament to make laws affecting the Irish Free State in any case where, in accordance with constitutional practice, Parliament would make laws affecting other self-governing Dominions". In 1924, Kevin O'Higgins

Kevin Christopher O'Higgins (; 7 June 1892 – 10 July 1927) was an Irish politician who served as Vice-President of the Executive Council and Minister for Justice from 1922 to 1927, Minister for External Affairs from June 1927 to July 1927 a ...

, the Free State's Vice-President of the Executive Council, declared that "Ireland secured by that 'surrender' he Treatya constitutional status equal to that of Canada. 'Canada,' said the late Mr. Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law (; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a Canadi ...

,' is by the full admission of British statesmen equal in status to Great Britain and as free as Great Britain'. The constitutional status of Ireland, therefore, as determined by the Treaty of 1921, is a status of co-equality with Britain within the British Commonwealth. The second Article of the Constitution of the Free State", he added, "declares that 'All powers of Government and all authority, legislative, executive and judicial, in Ireland are derived from the people of Ireland' ".

Motions of approval of the Report of the Commonwealth Conference had been passed by the Dáil and Seanad in May 1931 and the final form of the Statute of Westminster included the Irish Free State among the Dominions the British Parliament could not legislate for without the Dominion's request and consent. Originally, the UK government had wanted to exclude from the Statute of Westminster the legislation underpinning the 1921 treaty, from which the Free State's constitution had emerged. Executive Council President (Prime Minister) W. T. Cosgrave objected, although he promised that the Executive Council would not amend the legislation unilaterally. The other Dominions backed Cosgrave and, when an amendment to similar effect was proposed at Westminster by John Gretton, parliament duly voted it down. When the statute became law in the UK, Patrick McGilligan, the Free State Minister for External Affairs, stated: "It is a solemn declaration by the British people through their representatives in Parliament that the powers inherent in the Treaty position are what we have proclaimed them to be for the last ten years." He went on to present the statute as largely the fruit of the Irish Free State's efforts to secure for the other Dominions the same benefits it already enjoyed under the treaty. The Statute of Westminster had the effect of granting the Irish Free State internationally recognised independence.

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

led Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil ( ; ; meaning "Soldiers of Destiny" or "Warriors of Fál"), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party (), is a centre to centre-right political party in Ireland.

Founded as a republican party in 1926 by Éamon de ...

to victory in the Irish Free State election of 1932 on a platform of republicanising the Irish Free State from within. Upon taking office, de Valera began removing the monarchical elements of the Constitution, beginning with the Oath of Allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to a monarch or a country. In modern republics, oaths are sworn to the country in general, or to the country's constitution. For ...

. De Valera initially considered invoking the Statute of Westminster in making these changes, but John J. Hearne advised him not to. Abolishing the Oath of Allegiance in effect abrogated the 1921 treaty. Generally, the British thought that this was morally objectionable but legally permitted by the Statute of Westminster. Robert Lyon Moore, a Southern Unionist

In the United States, Southern Unionists were white Southerners living in the Confederate States of America and the Southern Border States opposed to secession. Many fought for the Union during the Civil War. These people are also referred t ...

from County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county of the Republic of Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is the northernmost county of Ireland. The county mostly borders Northern Ireland, sharing only a small b ...

, challenged the legality of the abolition in the Irish Free State's courts and then appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 August ...

(JCPC) in London. However, the Irish Free State had also abolished the right of appeal to the JCPC. In 1935, the JCPC ruled that both abolitions were valid under the Statute of Westminster.''Moore v Attorney General''9351 I.R. The Irish Free State, which in 1937 was renamed ''Ireland'', left the Commonwealth on 18 April 1949 upon the

coming into force

In law, coming into force or entry into force (also called commencement) is the process by which legislation, regulations, treaties and other legal instruments come to have legal force and effect. The term is closely related to the date of this ...

of The Republic of Ireland Act 1948.

New Zealand

TheParliament of New Zealand

The New Zealand Parliament () is the unicameral legislature of New Zealand, consisting of the Sovereign and the New Zealand House of Representatives. The King is usually represented by his governor-general. Before 1951, there was an upper ch ...

adopted the Statute of Westminster by passing its Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1947 in November 1947. The New Zealand Constitution Amendment Act, passed the same year, empowered the New Zealand Parliament to change the constitution, but did not remove the ability of the British Parliament to legislate regarding the New Zealand constitution. The remaining role of the British Parliament was removed by the New Zealand Constitution Act 1986 and the Statute of Westminster was repealed in its entirety.

Newfoundland

TheDominion of Newfoundland

Newfoundland was a British dominion in eastern North America, today the modern Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It included the island of Newfoundland, and Labrador on the continental mainland. Newfoundland was one of the orig ...

never adopted the Statute of Westminster, especially because of financial troubles and corruption there. By request of the Dominion's government, the United Kingdom established the Commission of Government

The Commission of Government was a non-elected body that governed the Dominion of Newfoundland from 1934 to 1949. Established following the collapse of Newfoundland's economy during the Great Depression, it was dissolved when the dominion became ...

in 1934, resuming direct rule of Newfoundland. That arrangement remained until Newfoundland became a province of Canada in 1949 following referendums on the issue in 1948. The Statute of Westminster became applicable to Newfoundland when it was admitted to Canada.

Union of South Africa

Although theUnion of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

was not among the Dominions that needed to adopt the Statute of Westminster for it to take effect, two laws — the Status of the Union Act, 1934, and the Royal Executive Functions and Seals Act, 1934 — were passed to confirm South Africa's status as a fully sovereign state.

Implications for succession to the throne

The preamble to the Statute of Westminster sets out a guideline for changing the rules of succession to

The preamble to the Statute of Westminster sets out a guideline for changing the rules of succession to the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

. The second paragraph of the preamble to the statute reads:

Though a preamble is not considered to have the force of statute law, that of the Statute of Westminster has come to be a constitutional convention, which "has always been treated in practice as though it were a binding requirement". The convention was then adopted by every country that subsequently gained its independence from Britain and became a Commonwealth realm.

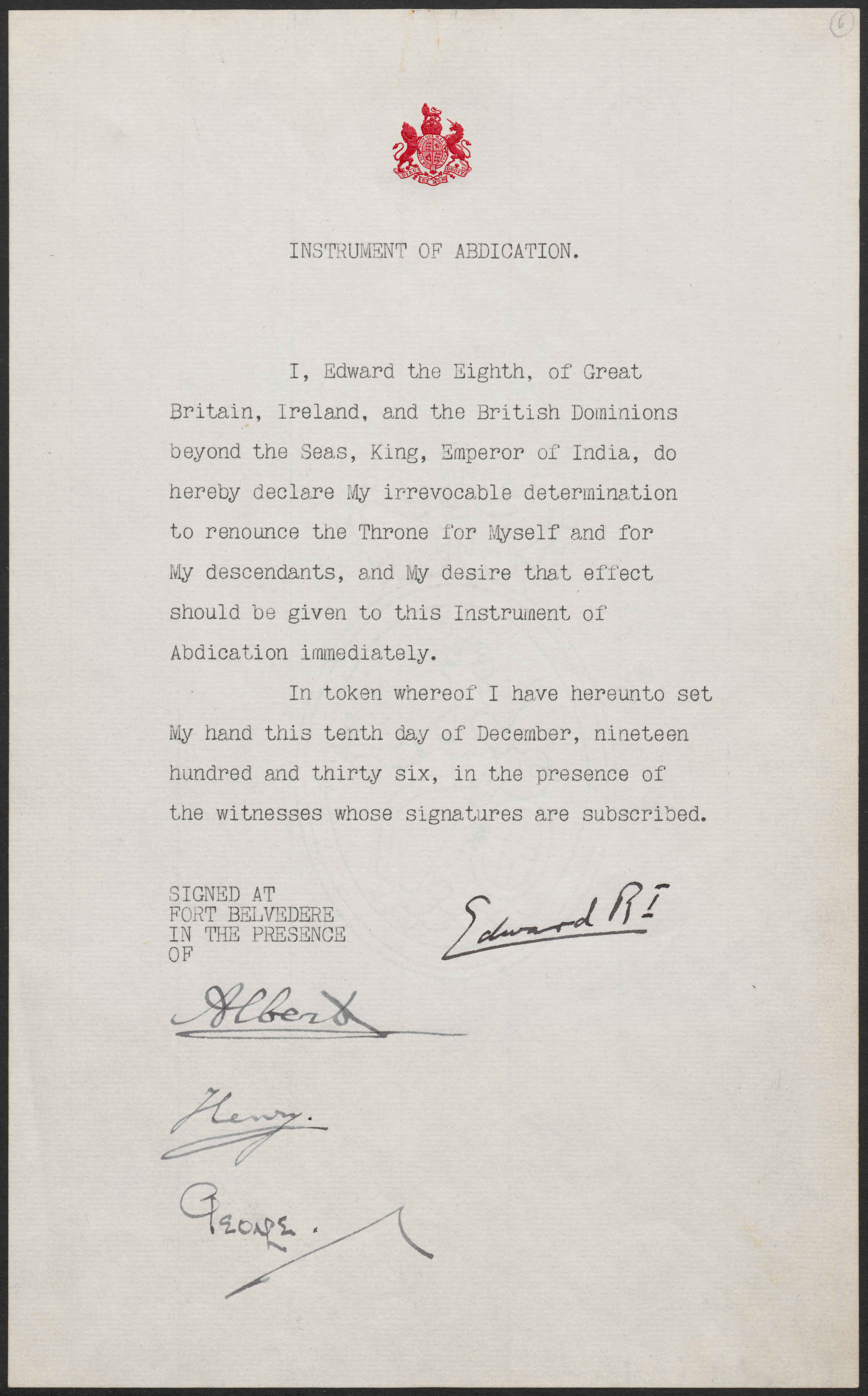

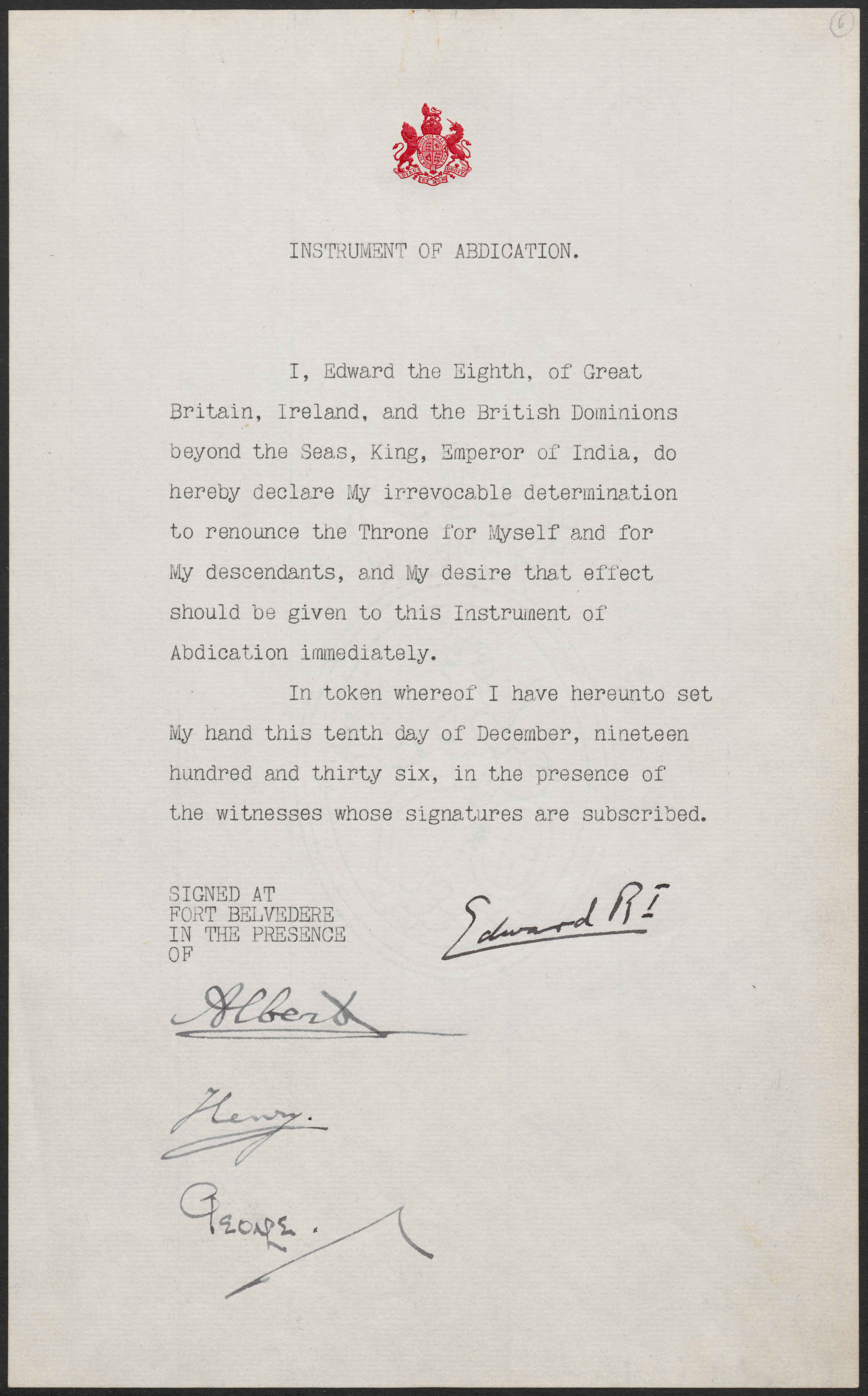

Abdication of King Edward VIII

During the

During the abdication crisis

In early December 1936, a constitutional crisis in the British Empire arose when King Edward VIII proposed to marry Wallis Simpson, an American socialite who was divorced from her first husband and was in the process of divorcing her second.

T ...

in 1936, British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

consulted the Commonwealth prime ministers at the request of King Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, from 20 January ...

. The King wanted to marry Wallis Simpson, whom Baldwin and other British politicians considered unacceptable as Queen, as she was an American divorcée. Baldwin was able to get the then-five Dominion prime ministers to agree with this and, thus, register their official disapproval at the King's planned marriage. The King later requested the Commonwealth prime ministers be consulted on a compromise plan, in which he would wed Simpson under a morganatic marriage

Morganatic marriage, sometimes called a left-handed marriage, is a marriage between people of unequal social rank, which in the context of royalty or other inherited title prevents the principal's position or privileges being passed to the spou ...

, pursuant to which she would not become queen. Under Baldwin's pressure, this plan was also rejected by the Dominions. All of these negotiations occurred at a diplomatic level and never went to the Commonwealth parliaments. The enabling legislation that allowed for the actual abdication (His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936

His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936 ( 1 Edw. 8. & 1 Geo. 6. c. 3) is the act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that recognised and ratified the abdication of King Edward VIII and passed succession to his brother King George ...

) did require the assent of each Dominion parliament to be passed and the request and consent of the Dominion governments so as to allow it to be part of the law of each Dominion. For expediency and to avoid embarrassment, the British government had suggested the Dominion governments regard whoever is monarch of the UK to automatically be their monarch, but the Dominions rejected this. Prime Minister of Canada William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who was the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Liberal ...

pointed out that the Statute of Westminster required Canada's request and consent to any legislation passed by the British Parliament before it could become part of Canada's laws and affect the line of succession in Canada. The text of the British act states that Canada requested and consented (the only Dominion to formally do both) to the act applying in Canada under the Statute of Westminster, while Australia, New Zealand, and the Union of South Africa simply assented.

In February 1937, the Parliament of South Africa

The Parliament of the Republic of South Africa is South Africa's legislature. It is located in Cape Town; the country's legislative capital city, capital.

Under the present Constitution of South Africa, the bicameralism, bicameral Parliamen ...

formally gave its assent by passing His Majesty King Edward the Eighth's Abdication Act, 1937

His Majesty King Edward the Eighth's Abdication Act, 1937 (Act No. 2 of 1937) was an act of Parliament, act of the Parliament of South Africa that ratified the Edward VIII abdication crisis, abdication of King Edward VIII and the succession to th ...

, which declared that Edward VIII had abdicated on 10 December 1936; that he and his descendants, if any, would have no right of succession to the throne; and that the Royal Marriages Act 1772 would not apply to him or his descendants, if any.May, H. J. (1949). ''The South African Constitution''. The move was largely done for symbolic purposes, in an attempt by Prime Minister J. B. M. Hertzog to assert South Africa's independence from Britain. In Canada, the federal Parliament passed the Succession to the Throne Act, 1937, to assent to His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act and ratify the government's request and consent to it.

In the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

used the abdication of King Edward VIII as an opportunity to remove all explicit mention of the monarch from the Constitution of the Irish Free State

The Constitution of the Irish Free State () was adopted by Act of Dáil Éireann sitting as a constituent assembly on 25 October 1922. In accordance with Article 83 of the Constitution,

, through the Constitution (Amendment No. 27) Act 1936, passed on 11 December 1936. The following day, the External Relations Act provided for the King to carry out certain diplomatic functions, if authorised by law; the same act also brought Edward VIII's Instrument of Abdication into effect for the purposes of Irish law (s. 3(2)). A new Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland (, ) is the constitution, fundamental law of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executi ...

, with a president, was approved by Irish voters in 1937, with the Irish Free State becoming simply "Ireland", or, in the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

, . The position of head of state of Ireland remained unclear until 1949, when Ireland unambiguously became a republic outside the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

by enacting The Republic of Ireland Act 1948. Between 1937 and 1949, King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

was recognised under the External Relations Act as the external head of state, while the President of Ireland

The president of Ireland () is the head of state of Republic of Ireland, Ireland and the supreme commander of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Irish Defence Forces. The presidency is a predominantly figurehead, ceremonial institution, serving as ...

served as the internal head of state as a replacement for the Governor-General of the Irish Free State

The governor-general of the Irish Free State () was the official representative of the sovereign of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1936. By convention, the office was largely ceremonial. Nonetheless, it was controversial, as many Irish Nat ...

as from 1938, when Douglas Hyde

Douglas Ross Hyde (; 17 January 1860 – 12 July 1949), known as (), was an Irish academic, linguist, scholar of the Irish language, politician, and diplomat who served as the first president of Ireland from June 1938 to June 1945. He was a l ...

was elected. Ireland was both a Dominion and a de-facto republic, as it was still within the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

.

Commemoration in Canada

In Canada, 11 December is commemorated Statute of Westminster Day. The Royal Union Flag (as the Union Jack is called by law in Canada) is flown by federal buildings where a second flagpole is available to mark the day.See also

* Chanak Crisis * Commonwealth of Nations membership criteria *Westminster system

The Westminster system, or Westminster model, is a type of parliamentary system, parliamentary government that incorporates a series of Parliamentary procedure, procedures for operating a legislature, first developed in England. Key aspects of ...

* Canadian sovereignty

Notes

References

Further reading

* Bailey, Kenneth H. "The Statute of Westminster." ''Australian Quarterly'' 3.12 (1931): 24–46online

* Mansergh, Nicholas. ''Survey of British Commonwealth affairs: problems of external policy, 1931–1939'' (Oxford University Press, 1952). * Nicolson, Harold. ''King George V'' (1953) pp 470–488

online

* Wheare, K. C. ''The Statute of Westminster, 1931'' (Clarendon Press, 1933). * Wheare, K. C. ''The Statute of Westminster and dominion status'' (Oxford University Press, 1953).

External links

Digital reproduction of the Original Act on the Parliamentary Archives catalogue

{{DEFAULTSORT:Statute of Westminster 1931 Commonwealth realms 1931 in British law United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1931 Australian constitutional law History of the British Empire History of the Commonwealth of Nations History of Newfoundland and Labrador Political charters 1931 in international relations Sovereignty British constitutional laws concerning Ireland Australia–United Kingdom relations Canada–United Kingdom relations Ireland–United Kingdom relations New Zealand–United Kingdom relations South Africa–United Kingdom relations December 1931 Australia and the Commonwealth of Nations Canada and the Commonwealth of Nations Ireland and the Commonwealth of Nations New Zealand and the Commonwealth of Nations South Africa and the Commonwealth of Nations United Kingdom and the Commonwealth of Nations Constitution of Canada December 1931 in the United Kingdom