St Mary The Virgin's Church, Aylesbury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

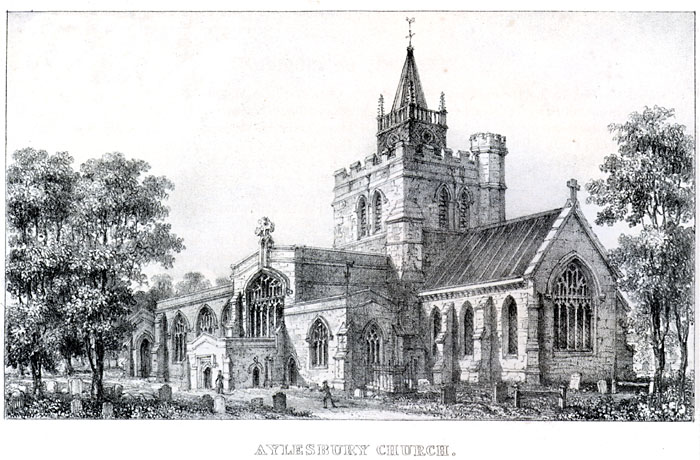

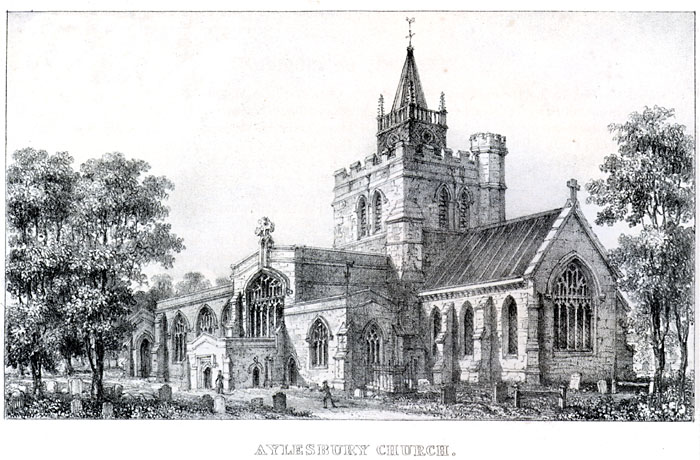

The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Aylesbury, is an

One of the most interesting portions of church is that of the

One of the most interesting portions of church is that of the

In the times of the

In the times of the

Extensive renovations works were carried out after a report from the 1830s. Prior to the restoration of the church the mural tablets were distributed in all parts of the building, but were mostly erected in the

Extensive renovations works were carried out after a report from the 1830s. Prior to the restoration of the church the mural tablets were distributed in all parts of the building, but were mostly erected in the

In the 1970s the church was again considered perilously unstable, and at one time appeared to be facing demolition.

In January 1976 following storm damage the battlemented parapet at the top of the tower was removed.

Funds were raised and the church was closed in April 1978 for the work to commence. The building was virtually gutted so that a major restoration project could start. It was planned over the coming year to spend more than £250,000 to change it to a dual-purpose building for both religious and social activities. The work was completed within a year and a new; internal layout, floor, lighting, heating system etc. was installed.

A

In the 1970s the church was again considered perilously unstable, and at one time appeared to be facing demolition.

In January 1976 following storm damage the battlemented parapet at the top of the tower was removed.

Funds were raised and the church was closed in April 1978 for the work to commence. The building was virtually gutted so that a major restoration project could start. It was planned over the coming year to spend more than £250,000 to change it to a dual-purpose building for both religious and social activities. The work was completed within a year and a new; internal layout, floor, lighting, heating system etc. was installed.

A

A Church Near You contains information about parish churches and the services and events that take place there

Classical music at St Mary's Church, Aylesbury

{{DEFAULTSORT:Saint Mary the Virgin, Aylesbury Aylesbury Diocese of Oxford Rebuilt churches in the United Kingdom Grade I listed churches in Buckinghamshire

Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

church of the Diocese of Oxford

The Diocese of Oxford is a Church of England diocese that forms part of the Province of Canterbury. The diocese is led by the Bishop of Oxford (currently Steven Croft (bishop), Steven Croft), and the bishop's seat is at Christ Church Cathedral, ...

, in the centre of the town of Aylesbury

Aylesbury ( ) is the county town of Buckinghamshire, England. It is home to the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery and the Aylesbury Waterside Theatre, Waterside Theatre. It is located in central Buckinghamshire, midway between High Wycombe and Milt ...

. There is evidence of a church from Saxon times, but the present building was built sometime between 1200 and 1250, with various additions and alterations in the 14th, 15th, 19th and 20th century.

The church is one of the most recognisable sights of Aylesbury; its ornate clock tower dominates the skyline. The church is currently a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

as it is a building of exceptional interest.

History

Saxon period

Aylesbury

Aylesbury ( ) is the county town of Buckinghamshire, England. It is home to the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery and the Aylesbury Waterside Theatre, Waterside Theatre. It is located in central Buckinghamshire, midway between High Wycombe and Milt ...

possessed a church in Saxon times; 19th-century renovations to the chapel revealed the remains of an ancient crypt

A crypt (from Greek κρύπτη (kryptē) ''wikt:crypta#Latin, crypta'' "Burial vault (tomb), vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, Sarcophagus, sarcophagi, or Relic, religiou ...

, with stone steps leading from the church in the west end of the crypt, and were uncovered as fully as possible without encroaching on the south transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

. There is one prominent arch in it, which those competent to decide have unhesitatingly pronounced to be Saxon

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

. The crypt was probably the remains of an old Saxon church, possibly dating from circa 571 when Aylesbury was a Saxon settlement known as Aeglesburge.

Probably in troublous times this subterraneous chamber was used for worship but later it appears to have been used as a charnel house

A charnel house is a vault or building where human skeletal remains are stored. They are often built near churches for depositing bones that are unearthed while digging graves. The term can also be used more generally as a description of a plac ...

: piles of human bones were found within. These were removed and re-interred in the churchyard

In Christian countries, a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church (building), church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster S ...

.

It is not impossible that this may have been the very site of the Saxon

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

building where St. Osyth is said to have been buried in the 9th century. St. Osyth's burial site in Aylesbury became a site of great, though unauthorised pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a travel, journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) w ...

; following a papal decree

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden seal ('' bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal bulls have been in use at l ...

in 1500, the bones were removed from the church and buried in secret. However much, if any, of this has a historical basis; it is even uncertain whether there were two Osyths or one, since both Aylesbury and Chich claim her relics. However, what appears to be known is that following her death in AD 700 her father, King Redwald (in some accounts Penda), and mother, Wilburga, took her to Aylesbury to be interred.

12th century

The existence of an earlier building to the one now standing may be inferred from the beautiful Normanfont

In metal typesetting, a font is a particular size, weight and style of a ''typeface'', defined as the set of fonts that share an overall design.

For instance, the typeface Bauer Bodoni (shown in the figure) includes fonts " Roman" (or "regul ...

found within the church and the existence of other artefacts of the same age. These were found buried in debris beneath the church in the 19th century. The font in particular was found in three fragments and work was done to repair it. This font can be found at the west end of the church today and has given its name to a particular style of font known as the "Aylesbury Fonts". These fonts are normally dated late in the 12th century around the years 1170 to 1190.

The early ecclesiastical history of Aylesbury is confusing and difficult to unravel. The church was a prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the choir ...

in Lincoln Cathedral

Lincoln Cathedral, also called Lincoln Minster, and formally the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln, is a Church of England cathedral in Lincoln, England, Lincoln, England. It is the seat of the bishop of Lincoln and is the Mo ...

. It will be seen that the Prebendary of Aylesbury was attached to the See of Lincoln

The Diocese of Lincoln forms part of the Province of Canterbury in England. The present diocese covers the ceremonial county of Lincolnshire.

History

The diocese traces its roots in an unbroken line to the Pre-Reformation Diocese of Leice ...

as early as 1092. An early account states "It is said that a Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of Nort ...

, desired by the Pope, give the Personage of Aylesbury to a stranger, a kinsman of his, found means to make it a Prebend, and to incorporate it to Lincoln Church." Thus, in the reign of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, Aylesbury Church was part of the Deanery of Lincoln, and a separate stall in that cathedral was set aside for the dean.

During excavation work in recent years a 12th-century cloister and a conduit pipe were identified.

13th century

The church as it stands today is supposed to have been erected at some date between 1200 and 1250 with various additions and alterations during the reign of either King John orHenry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of John, King of England, King John and Isabella of Ang ...

. Originally the church was a strictly cruciform

A cruciform is a physical manifestation resembling a common cross or Christian cross. These include architectural shapes, biology, art, and design.

Cruciform architectural plan

Christian churches are commonly described as having a cruciform ...

design which is to say with a; chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

, nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

, transepts

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") churches, in particular within the Romanesque and Gothic Christian church architectu ...

and tower. It still retains substantially that form, though altered and modified at various periods.

During the 11th through 14th centuries, a wave of building of cathedrals

A cathedral is a church (building), church that contains the of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, Annual conferences within Methodism, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually s ...

and smaller parish churches occurred across Western Europe. Aylesbury seems to have been part of this. In addition to being a place of worship, the church at this time would have been used by the community in other ways. It could have served as a meeting place for guilds

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

or a hall for banquet

A banquet (; ) is a formal large meal where a number of people consume food together. Banquets are traditionally held to enhance the prestige of a host, or reinforce social bonds among joint contributors. Modern examples of these purposes inc ...

s. Mystery plays

Mystery plays and miracle plays (they are distinguished as two different forms although the terms are often used interchangeably) are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the represe ...

were sometimes performed, and they might also be used for fairs. The church could have also been used as a place to thresh and store grain.

14th century

One of the most interesting portions of church is that of the

One of the most interesting portions of church is that of the Lady Chapel

A Lady chapel or lady chapel is a traditional British English, British term for a chapel dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, particularly those inside a cathedral or other large church (building), church. The chapels are also known as a Mary chape ...

which is a beautiful erection of the 14th century. In this chapel an old sedilia

In church architecture, sedilia (plural of Latin ''sedīle'', "seat") are seats, typically made of stone, located on the liturgical south side of the altar—often within the chancel—intended for use by the officiating priest, deacon, an ...

(stone seats, found on the liturgical south side of an altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religion, religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, Church (building), churches, and other places of worship. They are use ...

) was found in the wall in their proper position.

It is supposed that the old fabric of the church extended no farther than the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

, having a high pitched roof springing from the walls. The light thus obtained being insufficient, it is thought that the clerestory

A clerestory ( ; , also clearstory, clearstorey, or overstorey; from Old French ''cler estor'') is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye-level. Its purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both.

Historically, a ''clerestory' ...

, and the flat roof, were added in the 15th century. The east ends of the north and south chapels were probably extended about the same time, so as to form two larger chapels known today as the Chapel of St George and the Chapter House

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole communi ...

.

15th century

In 1450, a religious institution called the Guild of St Mary was founded in Aylesbury byJohn Kemp

John Kemp ( 1380 – 22 March 1454) was a medieval English cardinal, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor of England.

Biography

Kemp was the son of Thomas Kempe, a gentleman of Olantigh, in the parish of Wye near Ashford, Ke ...

, Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

. Known popularly as the Guild of Our Lady it became a meeting place for local dignitaries and a hotbed of political intrigue. The guild was influential in the final outcome of the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses, known at the time and in following centuries as the Civil Wars, were a series of armed confrontations, machinations, battles and campaigns fought over control of the English throne from 1455 to 1487. The conflict was fo ...

. Its premises at the Chantry in Church Street, Aylesbury, are still there, though today the site is occupied mainly by almshouses

An almshouse (also known as a bede-house, poorhouse, or hospital) is charitable organization, charitable public housing, housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the Middle Ages. They were often built for the povert ...

. It is likely the incumbent at St Mary's would have been paid to perform a stipulated number of masses during a stipulated period of time for the guild in the chapel.

According to a tablet formerly in the church and dated as far back as 1494, John Stone of Aylesbury gave by will two tenements to the parish. The rents of which were to be applied to maintain a clock and chimes in the tower of Aylesbury Church for ever.

The tower piers began to fail at an early period, and from time to time various expedients were resorted to, to strengthen them. An arch between the south-east pier and the transept must evidently have been frightfully crushed as early at least as the 15th century when it was blocked up and the pier buttresses both towards the transept and the lady chapel

A Lady chapel or lady chapel is a traditional British English, British term for a chapel dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, particularly those inside a cathedral or other large church (building), church. The chapels are also known as a Mary chape ...

. At the same time the southern and eastern arches of the tower itself appear to have been much injured and to have lost their true curves. It might possibly have been about the same time that the arch on the west side of the transept was walled up and the south-west pier of the tower buttressed on its south side.

During this period it is thought the Lady Chapel

A Lady chapel or lady chapel is a traditional British English, British term for a chapel dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, particularly those inside a cathedral or other large church (building), church. The chapels are also known as a Mary chape ...

and sacristy

A sacristy, also known as a vestry or preparation room, is a room in Christianity, Christian churches for the keeping of vestments (such as the alb and chasuble) and other church furnishings, sacred vessels, and parish records.

The sacristy is us ...

(now called the vestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government of a parish in England, Wales and some English colony, English colonies. At their height, the vestries were the only form of local government in many places and spen ...

) was constructed on the east side of the north and south transept respectively. The sacristy is to appearances the oldest part of the building today. An oaken wardrobe in which is an ingeniously incorporated a swinging horse on which the priest's vestments were hung is still found in the church to this day and dates from the 15th century. There is also a strong locker in which it is supposed the sacred vessels were deposited. Above the sacristy is a room called the priest's chamber or priest's hole. The walls of this corner of the building are of immense strength, and the door is a very massive and remarkable one of the 15th century.

16th century

At a much later period (as is shown by the date 1596 upon the stonework) the remaining sides of the south-west pier were encased in stonework. A little later still in 1599 the same operation was performed on the north-west pier, and probably at the same time the arch abutting against it was walled up.King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

had himself declared Supreme Head of the Church in England in February 1531. The following acts which led to the dissolution of the monasteries impinged relatively little on English parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

church activity. Parishes that had formerly paid their tithes to support a religious house, now paid them to a lay impropriator, but rectors, vicars and other incumbents remained in place, their incomes unaffected and their duties unchanged. In 1534 the church became part of the newly formed Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, forever separated from the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

In 1536 almost a third of the county of Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (, abbreviated ''Bucks'') is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-east, Hertfordshir ...

became the personal property of King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

. Henry VIII was also responsible for making Aylesbury the official county town over Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

, which he is alleged to have been done in order to curry favour with Thomas Boleyn so that he could marry his daughter Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

. This set the church on a path of expansion to the church it is today.

Under his son, King Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

, more Protestant-influenced forms of worship were adopted. Under the leadership of the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a Oxford Martyrs, martyr ...

, a more radical reformation proceeded. A new pattern of worship was set out in the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

'' (1549 and 1552).

Henry VIII and his son Edward VI dismissed Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and its trimmings. Then pro-Catholic Mary Tudor became queen. She attempted to re-establish the Catholic faith, including efforts to replace damaged, defaced and destroyed church artefacts. Mary was too late to prevent the whitewashing of church interiors and many irreplaceable wall paintings were lost.

In the north transept is an alabaster monument to Lady Lee, wife of Sir Henry Lee of Quarrendon, personal Champion to Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

. It was formerly profusely ornamented with gold and colouring and is of the time of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

as Lady Lee died in 1584.

Aylesbury Grammar School

Aylesbury Grammar School is an 11–18 boys grammar school in Aylesbury, in the England, English county of Buckinghamshire, which educates approximately 1300 boys.

Founded in 1598 by Sir Henry Lee, Champion of Queen Elizabeth I, Aylesbury Gramm ...

was founded in 1598 following a bequest from Sir Henry Lee and its first home was inside the church. The grammar school ran from 9am and 2pm. One of the trustees of the school was the Vicar of Aylesbury

17th century

In 1611 the Aylesbury Grammar School moved to what was then church buildings. These buildings now house the County Museum. The school remained here until 1907. In 1622 the south-east pier underwent a secondbuttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient (typically Gothic) buildings, as a means of providing support to act ...

ing, and at perhaps some other period the casing was built round that to the north-east, and its arches walled up. This is proof that in one instance at least (that of the south-west pier) the second casing failed at an early date, as is shown by the large clamps which have been added to it. There have subsequently there been continued failures in casing of both of the western piers.

On Aylesbury Church there are no monuments from the 17th century or before, and it did not at the time of its restoration in the 18th century contain a single particle of ancient coloured glass. Therefore, the church during this period is said to have undergone some exceedingly rough usage. During restoration work in the 19th century, they opened some of the closed archways prior to beginning work. Injuries to the building were to be observed inflicted on the ornamental stone work, which could not have been the result of accident. This damage was ascribed to the period of the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

during the reign of King Charles I. Exposed as the Aylesbury district was to the full force of the mischievous effects of the civil commotions of that period, it would indeed have been extraordinary if this church above all others had escaped the ravages and excesses of those unfortunate times, when the noblest ecclesiastical structures of our country were plundered, defamed, and defaced. Let us not forget the so-called Battle of Aylesbury on 1 November 1642. Indeed, in August 1642, Nehemiah Wharton, a Parliamentarian soldier, writes from Aylesbury, telling his friends how they attacked a man called Penruddock, whom he called a Papist

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

. He said the attack was because he had been "basely affronted by Penruddock and his dog". Finally he adds that he and his men "showed their zeal" and "got into the church, defaced the ancient and sacred glazed pictures, and burned the holy rails".

A description of the church says how there was an old gallery in the church with its bird-cage pew. This pew was completely enclosed with lattice work and its front was ornamented with filigree

Filigree (also less commonly spelled ''filagree'', and formerly written ''filigrann'' or ''filigrene'') is a form of intricate metalwork used in jewellery and other small forms of metalwork.

In jewellery, it is usually of gold and silver, m ...

work, presenting the appearance of a box at the opera, and thus named the bird-cage. This was the old manor pew, and was occupied by the judges and high sheriff at the assize

The assizes (), or courts of assize, were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ex ...

sermon, and used upon other state occasions. The church also had a pulpit at the front which was nicknamed by the congregation a 'three-decker'.

Some of the pews in the body of the church were fitted with brass rails and hangings to make them more private. In the north chapel were the high pews which were raised some feet above the floor and reached by three or four steps. The whole of the nave was filled with panelled pews over which the occupiers claimed exclusive and permanent right; it was thought something grand to be known as the owner of a 'faculty pew'. The divisions which were exceedingly high, were adorned according to the various owners; some were lined with blue cloth and bedizened with an abundance of large brass-headed nails; others would be scarlet; green baize was the prevailing 'comfort', whilst some of less pretensions were satisfied with paint. These pews were of all shapes and sizes, without the least pretense to uniformity. There was a jealous feeling respecting possession of pews; and it was a common practice for many of the owners to keep the doors carefully locked. ''When the wicked man'' came into church, his arrival was announced by the clicking of the locks of pew doors.

The Commissioners and Visitors appointed to purify the church in the Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, was the English form of government lasting from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659, under which the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotl ...

of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

listed the Rev John Barton of Aylesbury a 'scandalous minister' and it was voted that he would be expelled. On 8 July 1642 information in writing was given to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

that John Barton had spoken against the Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. As a result, he was sent for and delivered to Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

in custody of the Sergeant-at-Arms. John Barton did not deny the words and was committed to the 'Gatehouse' on 18 July, but discharged on 26 July of the same month. Subsequently, he was driven from the vicarage

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or Minister (Christianity), ministers of a given religion, serving as both a home and a base for the occupant's ministry. Residences of this type can have a variety of n ...

.

In 1691 it was arranged at a parish vestry that John Aylward who was a clockmaker, of Aylesbury was to have the tenements left by John Stone in 1494 for a period of 31 years at a peppercorn rent providing he erected and maintained a substantial clock and chimes in the tower of the church. The estate was described commonly as the Clock and Chimes Estate.

The tower of the church is crowned by a small spire which is believed to date from the reign of Charles II.

18th century

The pews mentioned were still present in the 18th century. The Prebendal House was at times unoccupied for considerable periods and during which no use was made of the family pew. In 1759 'Dear Dell' seems to have askedJohn Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English Radicalism (historical), radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlese ...

to allow him to use the unoccupied pew, but notwithstanding the cordiality subsisting between them, and the obligations John Wilkes was under to 'Dear Dell', he is refused. John Wilkes writes in reply, "I cannot lend you my pew tho' I wou'd willingly assist your piety. I will tell you the particular reason (which you cannot guess) when I see you."

In 1756 it was proposed that a gallery should be erected. It was also agreed that the 'middle aisle' of the church be 'cieled'.

Also in 1756 a charge appears in the Aylesbury churchwardens

A churchwarden is a laity, lay official in a parish or congregation of the Anglicanism, Anglican Communion, Lutheranism, Lutheran Churches or Catholicism, Catholic Church, usually working as a part-time volunteer. In the Anglican tradition, holde ...

book 'for setting the yew tree

Yew is a common name given to various species of trees.

It is most prominently given to any of various coniferous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Taxus'':

* European yew or common yew (''Taxus baccata'')

* Pacific yew or western yew ('' Taxus b ...

in the Churchyard'. It is not very clearly shown why. Old writers have explained its cultivation as necessary for the purpose of keeping up a stock of bows for archers

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a Bow and arrow, bow to shooting, shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting ...

, and others that it was planted to screen the church from the effects of storms and tempests.

In the year 1765 the state of the fabric of the church excited the serious attention of the parishioners and a Mr. Keen, a surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. These points are usually on the ...

, was called in to report on its condition. His report confirmed the opinion of those assembled in vestry which was that the building was in a very unsafe state and required re-erection. It was resolved that his report be printed and published and copies sent to all the owners of estates in the parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

with a request that they would pay after the rate of sixpence in the pound on their rentals for the space of ten years. This proposition does not seem to have been very popular as no further efforts were then made to obtain the money from them.

Before a general restoration of the church in the 19th century a portion only of the building, partitioned off from the transepts, was used for public worship. At this time the south transept resembled a marine store; this considerable part of the building was then used as the receptacle of all the paraphernalia of the parish fire brigade.

19th century

In the times of the

In the times of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, the stock of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

required for the local regiments was stored in the innermost parts of the church.

In 1821 the churchwardens

A churchwarden is a laity, lay official in a parish or congregation of the Anglicanism, Anglican Communion, Lutheranism, Lutheran Churches or Catholicism, Catholic Church, usually working as a part-time volunteer. In the Anglican tradition, holde ...

expended £250 in erecting a stable, coach house, and washhouse; this outlay was not satisfactory to the Charity Commissioners. These properties were situated somewhere in the vicinity of Temple Square.

Extensive renovations works were carried out after a report from the 1830s. Prior to the restoration of the church the mural tablets were distributed in all parts of the building, but were mostly erected in the

Extensive renovations works were carried out after a report from the 1830s. Prior to the restoration of the church the mural tablets were distributed in all parts of the building, but were mostly erected in the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

and north transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

.

The church had been under the process of what is called 'churchwardening' for many years, and a considerable debt was incurred for worse than useless patching. The real work of restoration commenced as far back as the year 1842, during the church wardenship of Mr. Fowler and Mr. Field. They first tried their hands on the interior of the south transept. For their services they received the thanks of a vestry, accompanied by a request that they would continue their labours. It was, however, found that the expenses would be very great, and it was hopeless to expect to raise anything like the sum required, by church-rates or appeals to the parishioners only.

A surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. These points are usually on the ...

from London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

had been consulted upon the state of the church many years before 1848, and his report was a very concise one. He gave it as his opinion that the church might probably stand until he got to Watford

Watford () is a town and non-metropolitan district with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Hertfordshire, England, northwest of Central London, on the banks of the River Colne, Hertfordshire, River Colne.

Initially a smal ...

, but that it would fall before he reached home. On 24 September 1848, during the Sunday morning service, the chimes being silenced as usual, the fastenings by which they were held gave way, and caused a great clatter in the tower. Many thought the prophecy made by the surveyor had come to pass and that the church was actually falling. There was a panic, and a great rush made by many of the congregation to escape from the supposed falling ruins; some scrambled over the tops of the pews, some tumbled over each other in attempting to make their way out, and for a time there was utter confusion. When the more timid had reached the churchyard

In Christian countries, a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church (building), church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster S ...

, and their fears had become somewhat allayed by finding that there was nothing whatever the matter, they returned to their seats, and the service was resumed and continued.

An 1848 survey by Sir Gilbert Scott revealed considerable problems with the foundations, and thus the walls and the roof.

At a vestry held in 1849, this report was taken into consideration. Mr. Tindal received a mandate from the Archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denomina ...

to do the necessary repairs to the fabric of the building. The object of the vestry, therefore, was to sanction the borrowing of £3,000 for the purposes of repairs. This vestry was an exceedingly stormy one, the borrowing of the money being vehemently opposed by the leading Nonconformists. The vestry decided in favour of the plan, and a poll of the parish was demanded. The poll remained open two days, and ended in a majority of 281 in favour of the motion for obtaining the money by borrowing. At the Easter

Easter, also called Pascha ( Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in t ...

vestry which followed soon after, Mr. Z. D. Hunt was chosen parish churchwarden, when he requested that he might be allowed to state in what spirit he took office. It appeared to him that the grant of £3,000 should be laid out with the most scrupulous care, and only for those repairs which were necessary in furnishing the poor with religious instruction. Not one shilling of this money should be laid out in decorations or ornamental work of any kind. He was determined to carry out this principle. He believed this view of the case was not a peculiar one, as it was announced by the members of the scheme at the vestry and he had no doubt that the decorations needed in the church would be done by subscription raised in another way. Pews, galleries, partitions, and other impediments were swept away and sold, and contracts entered into, not only for necessary repairs, but also for the restoration of the interior. The church was closed, and public worship held in the County Hall.

An ecclesiastical census was carried out throughout England on 30 March 1851 to record the attendance at all places of worship. The returns issued by St Mary's at this time was that on the Sunday morning 700 people were in the congregation with 180 in Sunday school giving a total of 880. On Sunday evening it records 800 people were in the congregation with 180 in Sunday school giving a total of 980.

On Whitsun

Whitsun (also Whitsunday or Whit Sunday) is the name used in Britain, and other countries among Anglicans and Methodists, for the Christian holy day of Pentecost. It falls on the seventh Sunday after Easter and commemorates the descent of the H ...

1851, the congregation again met in the church for public worship, but the restoration was far from being complete. The seats had not been erected, and the worshippers were accommodated with chairs. The restoration of the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

had not yet been begun.

In May 1852, a vestry was convened by the churchwardens for considering the best mode of raising the necessary for reseating the church and the principle that it should be effected by voluntary contributions was also approved.

In the autumn of 1853, the work was revived in earnest, the only delay being caused by disputes raised by some few of the parishioners with regard to their supposed rights to seats, some demanding to occupy the same sites on which their old pews formerly stood. The seating was not completed until 1854, and the finishing touches were not yet given to the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

. Opening services were held about this time. The chancel remained unfinished but the north side of it had been restored at the expense of the Prettyman family. The remainder was left nearly untouched, and for a considerable time it was screened off from the rest of the church. This restoration was at length carried out in its entirety at a cost of about £1,000, and the chancel was reopened in 1855.

The interior of the church had not long been finished when the idea of crowning the work by the restoration of the exterior was entertained. It was not however until 1865 this was set about in earnest. At a private meeting of the subscribers of the voluntary Church Service Fund, held at the vestry-place in March of that year, a report of Mr. Scott, dated 7 November 1864, was read. In July following a public vestry was held for submitting Mr. Scott's estimate and report. The difficulty appeared to be the raising of the requisite funds. The question to be decided was the expediency of raising £1,500 by rate, and the remainder by voluntary contribution; the vestry drifted into a discussion on church-rates. Some churchmen were in favour of making a rate, others were reluctant to launch into a parish squabble. At length Mr, Acton Tindal, who was churchwarden, stated that he accepted this upon the condition that he should not be called upon to levy a church-rate by any compulsory means, a statement which had considerable effect. A Restoration Committee was appointed. Finding the general feeling of the vestry to be opposed to a church-rate, the committee depended entirely upon the voluntary principle for support, and their appeal for the necessary funds was well responded to.

By the following September £1,558 had been subscribed, and the first contract was entered into for the restoration of the west end, which was commenced in the spring of 1866, and as subscriptions came in liberally, it was determined to carry out the work in a more thorough manner than was at first contemplated. All the coverings of rough cast, with the ugly plinths of Roman cement, were removed, and a handsome wall facing of stone substituted; the buttresses were rebuilt on solid foundations reaching down to the rock, and good stone plinths added, following as nearly as possible the old lines. The foundations are now even more substantial than when the church was first erected.

The exterior of the building was extensively repaired and straightened. The completion of the work of restoration was celebrated with thanksgiving services on 28 September 1869, on which occasion Dr. Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public sp ...

, Bishop of Oxford

The Bishop of Oxford is the diocesan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Oxford in the Province of Canterbury; his seat is at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. The current bishop is Steven Croft (bishop), Steven Croft, following the Confirm ...

, and Dr. Harold Browne

Edward Harold Browne (6 March 1811 – 18 December 1891) was a bishop of the Church of England.

Early life and education

Browne was born on 6 March 1811 at Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, the second son of Robert Browne of Morton House in Buck ...

, Bishop of Ely

The Bishop of Ely is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Ely in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese roughly covers the county of Cambridgeshire (with the exception of the Soke of Peterborough), together with ...

, now of Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

(a native of the town), preached sermons. The proceedings of the day were more than usually of an imposing character; the church was handsomely and extensively decorated, and the bells rang merrily; between the services a public luncheon was held in the Corn Exchange

A corn exchange is a building where merchants trade grains. The word "corn" in British English denotes all cereal grains, such as wheat and barley; in the United States these buildings were called grain exchanges. Such trade was common in towns ...

, which was largely attended. The sum of £800 was subscribed at the celebration of the re-opening, leaving little or nothing remaining, to clear off the whole of the liabilities of the restoration, which, from first to last, amounted to a sum approaching £16,000 (£731,000 today).

20th century

In the 1970s the church was again considered perilously unstable, and at one time appeared to be facing demolition.

In January 1976 following storm damage the battlemented parapet at the top of the tower was removed.

Funds were raised and the church was closed in April 1978 for the work to commence. The building was virtually gutted so that a major restoration project could start. It was planned over the coming year to spend more than £250,000 to change it to a dual-purpose building for both religious and social activities. The work was completed within a year and a new; internal layout, floor, lighting, heating system etc. was installed.

A

In the 1970s the church was again considered perilously unstable, and at one time appeared to be facing demolition.

In January 1976 following storm damage the battlemented parapet at the top of the tower was removed.

Funds were raised and the church was closed in April 1978 for the work to commence. The building was virtually gutted so that a major restoration project could start. It was planned over the coming year to spend more than £250,000 to change it to a dual-purpose building for both religious and social activities. The work was completed within a year and a new; internal layout, floor, lighting, heating system etc. was installed.

A refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monastery, monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminary, seminaries. The name ...

was constructed in the old south porch

A porch (; , ) is a room or gallery located in front of an entrance to a building. A porch is placed in front of the façade of a building it commands, and forms a low front. Alternatively, it may be a vestibule (architecture), vestibule (a s ...

of the church moving the main entrance to one on the south transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

.

21st century

The building is once again looking at requiring renovation. A large amount of money needs to be spent on re-roofing the South side of the church due to issues with the roof leaking in the southtransept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

, chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole communi ...

, and refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monastery, monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminary, seminaries. The name ...

.

Churchyard

Thechurchyard

In Christian countries, a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church (building), church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster S ...

of St Mary’s appears to have been much bigger in the Late Saxon

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

and medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

periods. Skeletons have been found at 12 Church Street in a water main trench and in the cellars of 14 Temple Square and 2 St Mary’s Square. Documentary evidence suggests that St Mary’s was the site of a late Saxon

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

minster. Other documentary evidence suggests there was an 11th-century mint based here under Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was King of England from 1042 until his death in 1066. He was the last reigning monarch of the House of Wessex.

Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. He succeede ...

.

Some late Saxon and medieval activity other than burials have been identified in this area, such as 10th- to 12th-century ditches, pits and wells, pottery and animal remains at the corner of Temple and Bourbon Streets after house demolition. A Saxon ditch and 12th- to 14th-century pits and wells were found in the excavations at the Prebendal, the site of a medieval manor. Place-name evidence suggests that Aylesbury

Aylesbury ( ) is the county town of Buckinghamshire, England. It is home to the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery and the Aylesbury Waterside Theatre, Waterside Theatre. It is located in central Buckinghamshire, midway between High Wycombe and Milt ...

may have been the site of a Saxon burh

A burh () or burg was an Anglo-Saxon fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new constru ...

, but there is little physical evidence for this apart from the ditch at the Prebendal.

Tradition tells us that Aylesbury Churchyard used to be the rendezvous for the idle and dissolute characters of the town. It also tells us that all manners of sports and games were carried on there including cock-shying and the like. Soldiers are reported to have been flogged there. No proofs now exist of such proceedings but it is not at all improbable they occurred.

Even as late as at the commencement of the 18th century it was usual to hold the borough elections in the churchyard

In Christian countries, a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church (building), church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster S ...

. The candidates, their nominators and seconders one after another mounted an old tomb (now removed), to address the constituents. When no contest followed, the proceedings ended here, but in the case of a poll an adjournment was made to the County Hall, where the subsequent proceedings were held. The nominations at the contested election of 1802 were made on this old tomb; this was the last occasion, as after the addition of the Hundred (county division)

A hundred is an administrative division that is geographically part of a larger region. It was formerly used in England, Wales, some parts of the United States, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Norway, and in Cumberland County in the British Colony o ...

in 1804, the election no longer being a town matter only, all the proceedings were transferred to the County Hall.

Whilst there are no ancient memorials on the north side, there is ample proof that the south side was so crowded with interments that further burials in that part were impossible; and, there being no other parish burial place, it was imperative to make use of the unpopular portion which had been avoided by former generations. The victims of the law at Aylesbury who met with ignominious deaths at the hands of the hangman, and whose bodies escaped the experiments of the anatomist, or were not given over to their friends for interment, were buried "behind Church", without Christian burial, and so were the bodies of suicides and wayfarers.

Aylesbury Churchyard was intersected by several useless public footways, now stopped up; an entrance existed at the western comer, from which a public path ran parallel with the Prebendal wall to the west end of the church; another path from the same entrance led to the south door.

There was a public way in a line with Parson's Fee into Church Row, and an open path from Church Row to the church. There was also an unauthorised straggling path eastward of the chancel; there was no outside fence, nor did anything like the present palisade exist; a decayed post and rail ran round on the north side, but it was so dilapidated as to be useless. The churchyard was "an open sepulchre" the boys of the Aylesbury Grammar School

Aylesbury Grammar School is an 11–18 boys grammar school in Aylesbury, in the England, English county of Buckinghamshire, which educates approximately 1300 boys.

Founded in 1598 by Sir Henry Lee, Champion of Queen Elizabeth I, Aylesbury Gramm ...

; indeed, the boys of the town generally, made a playground of it, till the damage done was so considerable that an old parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

beadle

A beadle, sometimes spelled bedel, is an official who may usher, keep order, make reports, and assist in religious functions; or a minor official who carries out various civil, educational or ceremonial duties on the manor.

The term has pre- ...

was appointed to concentrate his energies in keeping order in the burial place. Aylesbury must not be considered to have been singular in regard to these shortcomings, as they were general in bygone years.

As a burial place Aylesbury Churchyard was much overcrowded; and it was with difficulty that grave space could be found for an interment without disturbing the remains of an already existing occupant. It was found imperative to close it, and it was closed at the end of the year 1857; the cemetery in the Tring Road was then consecrated and opened. Occasionally interments take place in the churchyard.

Music

Music performs a role in St Mary's church and community life, particularly at formal worship, and other activities that take place in the building.Bells

In 1773 a new peal of bells was opened, probably with consecration. Three old bells were exchanged with Pack and Chapman ofLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

for new ones. The total sum subscribed was £106 4s. The saints' bell in the tower is the oldest. It bears the date of 1612, and 'G.T." probably the initials of the bell founder. Today there are a total of nine bells: the sanctus bell, the six from 1773 and two bells from 1850 made by Mears of London.

Organ

The originalchurch organ

Carol Williams performing at the West_Point_Cadet_Chapel.html" ;"title="United States Military Academy West Point Cadet Chapel">United States Military Academy West Point Cadet Chapel.

In music, the organ is a keyboard instrument of one or mo ...

, a gift of a Mrs Mary Pitches, was accepted at a vestry meeting in February 1782. At the meeting £20 a year was voted to an organist

An organist is a musician who plays any type of organ (music), organ. An organist may play organ repertoire, solo organ works, play with an musical ensemble, ensemble or orchestra, or accompany one or more singers or instrumentalist, instrumental ...

, the sum to be raised by equal taxation on all parish dwelling houses rateable to the poor. Mrs Pitches, at her death in 1800, bequeathed £500 to provide dividends to be paid to an appointed church organist.

This organ was built by Green of Lichfield

Lichfield () is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated south-east of the county town of Stafford, north-east of Walsall, north-west of ...

; it was improved in 1858, and probably little of the original instrument now remains.

The organ has occupied different positions in the church. First, it was erected in an organ loft gallery which filled the tower and faced the nave with the organist and choir sat at its front. It was afterwards removed to the centre of the west end close to the west door. It remained there for a short time, and at the general restoration of the church in the 19th century was placed in a chamber or recess in the north transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

. J. W. Walkers had a two-manual organ which they maintained until the 1978 refit. This was then moved by raising it high into the north transfer (allegedly to allow gymnastics to take place across the floor space underneath, which never did occur). Hill Norman and Beard took over maintenance and also installed a small 'Chester' pipe organ of five extended ranks into the north side west end of the church. The choir also moved to sing from underneath the west window on a gallery designed for the purpose. The new organ and rebuild was opened by recital organist Peter Hurford in 1979.

The organ stopped working several years ago and an electric organ takes its place. The original organ though remains in non-functioning condition.

Choir

The choir helps to lead worship each Sunday at the ParishEucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

. It also sings at special civic services, carol services, and weddings.

The Friends of St Mary's

The Friends of St Mary's organises concerts of classical music at the church, including an extended evening concert about once a month.See also

* Vicars of the Parish Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Aylesbury *Prebendaries of Aylesbury

The prebendaries of Aylesbury can be traced back to Ralph in 1092. The prebend of Aylesbury was attached to the See of Lincoln as early as 1092. An early account states ''"It is said that a Bishop of Lincoln, desired by the Pope, give the Personag ...

References

Further reading

*External links

A Church Near You contains information about parish churches and the services and events that take place there

Classical music at St Mary's Church, Aylesbury

{{DEFAULTSORT:Saint Mary the Virgin, Aylesbury Aylesbury Diocese of Oxford Rebuilt churches in the United Kingdom Grade I listed churches in Buckinghamshire

Aylesbury

Aylesbury ( ) is the county town of Buckinghamshire, England. It is home to the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery and the Aylesbury Waterside Theatre, Waterside Theatre. It is located in central Buckinghamshire, midway between High Wycombe and Milt ...