St. Louis World's Fair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World's Fair, was an

In 1904, St. Louis hosted a

In 1904, St. Louis hosted a  The fair's site, designed by George Kessler,

The fair's site, designed by George Kessler,

KESSLER, GEORGE E.

. Retrieved May 18, 2006. was located at the present-day grounds of Forest Park and on the campus of Washington University, and was the largest fair (in area) to date. There were over 1,500 buildings, connected by some of roads and walkways. It was said to be impossible to give even a hurried glance at everything in less than a week. The Palace of Agriculture alone covered some . Exhibits were staged by approximately 50 foreign nations, the

George Kessler, who designed many urban parks in Texas and the Midwest, created the master design for the Fair.

A popular myth says that

George Kessler, who designed many urban parks in Texas and the Midwest, created the master design for the Fair.

A popular myth says that

As with the

As with the  The huge bird cage at the

The huge bird cage at the  Festival Hall, designed by

Festival Hall, designed by  Completed in 1913, the Jefferson Memorial building was built near the main entrance to the Exposition, at Lindell and DeBalivere. It was built with proceeds from the fair, to commemorate

Completed in 1913, the Jefferson Memorial building was built near the main entrance to the Exposition, at Lindell and DeBalivere. It was built with proceeds from the fair, to commemorate  The Swedish Pavilion is still preserved in Lindsborg, Kansas. Designed by Swedish architect

The Swedish Pavilion is still preserved in Lindsborg, Kansas. Designed by Swedish architect

The

The

Frank E. Fillis produced what was supposedly "the greatest and most realistic military spectacle known in the history of the world". Different portions of the concession featured a

Frank E. Fillis produced what was supposedly "the greatest and most realistic military spectacle known in the history of the world". Different portions of the concession featured a

The Louisiana World's Fair was opened by President,

The Louisiana World's Fair was opened by President,

File:Robert Livingston33 1904 Issue-1c.jpg, Robert Livingston

File:Thomas Jefferson22 Issue of 1904-4c.jpg, Thomas Jefferson

File:Monroe 1904 Issue-3c.jpg, James Monroe

File:McKinley1904-7.jpg, William McKinley

File:Louisiana Purchase7 1903 Issue-10c-crop.jpg, Map of the Louisiana Purchase

online

by the governor of Missouri.

Official website of the BIE

1904 World's Fair Society

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Glass Plate Negatives Collection

i

Digital Collections

a

St. Louis Public Library

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Miscellaneous Digital Collection

of publications, tickets, programs, invitations, and fliers at St. Louis Public Library

* ttp://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsmi/awal.0659 An Edison company film of the Asia pavilion at the

History of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

''Final Report of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Commission'' at gutenberg

Arthur Younger Ford (1861–1926) Photograph Albums (University of Louisville Photographic Archives)

– includes 69 photos taken at the fair.

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition: The 1904 St. Louis World's Fair from the University of Missouri Digital Library

– scanned copies of nearly 50 books, pamphlets, and other related material from and about the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (The 1904 St. Louis World's Fair) including issues of the World's Fair Bulletin from June 1901 through the close of the Fair in December 1904.

– approximately 380 links

The World's Fair: Comprising the Official Photographic Views of the Universal Exposition Held in Saint Louis, 1904

Official Guide to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

Official Catalogue of Exhibits, Universal Exposition St. Louis 1904

Kiralfy's Louisiana Purchase Spectacle

The Opening: Universal Exposition, 1904

On The Pike

Inside an American Factory: Films of the Westinghouse Works, 1904

Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis, sung by S.H. Dudley in 1904

Celebrating the Louisiana Purchase

online exhibit by St. Louis Public Library

The Rhode Island Building: Louisiana Purchase Exposition St. Louis

from the Rhode Island State Archives

World's Fair St. Louis Official Ground Plan

from the Rhode Island State Archives *

At The Fair: The Grandness of the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Collection

finding aid at St. Louis Public Library

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Sheet Music Collection

finding aid a

St. Louis Public Library

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Lantern Slides Finding Aid

at th

St. Louis Public Library

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Official Photographer Photos Finding Aid

at th

St. Louis Public Library

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Photo Albums Finding Aid

at th

St. Louis Public Library

Louisiana Purchase Exposition: Postcard Collection Finding Aid

at th

St. Louis Public Library

Louisiana Purchase Exposition: Stereograph Cards Collection Finding Aid

at th

St. Louis Public Library

Louisiana Purchase Exposition: Truman Ward Ingersoll Stereograph Cards Collection Finding Aid

at th

St. Louis Public Library

{{Authority control * 1900s in St. Louis 1904 in Missouri Festivals established in 1904 Human zoos

international exposition

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition, is a large global exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a perio ...

held in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

, United States, from April 30 to December 1, 1904. Local, state, and federal funds totaling $15 million (equivalent to $ in ) were used to finance the event. More than 60 countries and 43 of the then-45 American states maintained exhibition spaces at the fair, which was attended by nearly 19.7 million people.

Historians generally emphasize the prominence of the themes of race and imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

, and the fair's long-lasting impact on intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

s in the fields of history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

, architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

, and anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

. From the point of view of the memory of the average person who attended the fair, it primarily promoted entertainment, consumer goods, and popular culture. The monumental Greco-Roman architecture of this and other fairs of the era did much to influence permanent new buildings and master plans of major cities.

Background

In 1904, St. Louis hosted a

In 1904, St. Louis hosted a world's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition, is a large global exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a perio ...

to celebrate the centennial of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

. The idea for such a commemorative event seems to have emerged early in 1898, with Kansas City

The Kansas City metropolitan area is a bi-state metropolitan area anchored by Kansas City, Missouri. Its 14 counties straddle the border between the U.S. states of Missouri (9 counties) and Kansas (5 counties). With and a population of more t ...

and St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

initially presented as potential hosts for a fair based on their central location within the territory encompassed by the 1803 land annexation.

The exhibition was grand in scale and lengthy in preparation, with an initial $5 million committed by the city of St. Louis through the sale of city bonds, authorized by the Missouri state legislature in April 1899. An additional $5 million was generated through private donations by interested citizens and businesses from around Missouri, a fundraising target reached in January 1901. The final installment of $5 million of the exposition's $15 million capitalization came in the form of earmarked funds that were part of a congressional appropriations bill passed at the end of May 1900. The fundraising mission was aided by the active support of President of the United States William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

, which was won by organizers in a February 1899 White House visit.

While initially conceived as a centennial celebration to be held in 1903, the actual opening of the St. Louis exposition was delayed until April 30, 1904, to allow for full-scale participation by more states and foreign countries. The exposition operated until December 1, 1904. During the year of the fair, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition supplanted the annual St. Louis Exposition of agricultural, trade, and scientific exhibitions which had been held in the city since the 1880s.

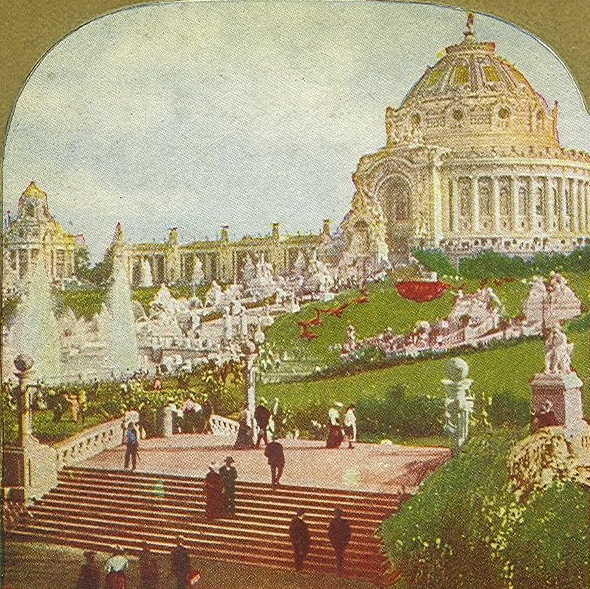

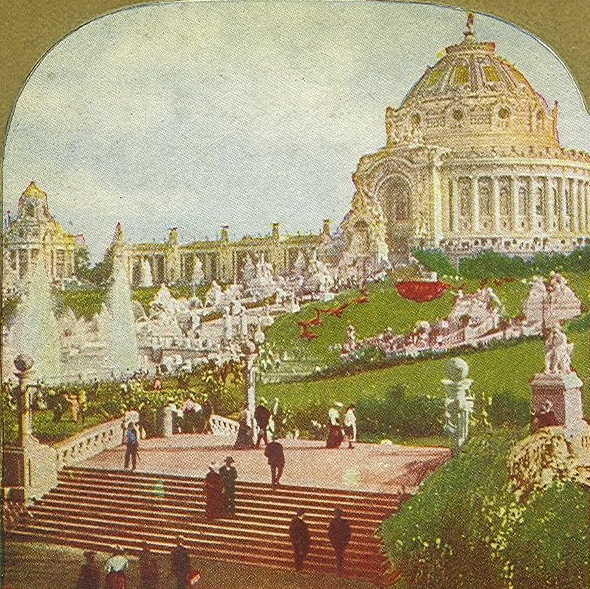

The fair's site, designed by George Kessler,

The fair's site, designed by George Kessler,Handbook of Texas Online

The Texas State Historical Association (TSHA) is an American nonprofit educational and research organization dedicated to documenting the history of Texas. It was founded in Austin, Texas, United States, on March 2, 1897. In November 2008, the ...

�KESSLER, GEORGE E.

. Retrieved May 18, 2006. was located at the present-day grounds of Forest Park and on the campus of Washington University, and was the largest fair (in area) to date. There were over 1,500 buildings, connected by some of roads and walkways. It was said to be impossible to give even a hurried glance at everything in less than a week. The Palace of Agriculture alone covered some . Exhibits were staged by approximately 50 foreign nations, the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

government, and 43 of the then-45 US states

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

. These featured industries, cities, private organizations and corporations, theater troupes, and music schools. There were also over 50 concession-type amusements found on "The Pike"; they provided educational and scientific displays, exhibits and imaginary 'travel' to distant lands, history and local boosterism

Boosterism is the act of promoting ("boosting") a town, city, or organization, with the goal of improving public perception of it. Boosting can be as simple as talking up the entity at a party or as elaborate as establishing a visitors' bureau.

...

(including Louis Wollbrinck's "Old St. Louis") and pure entertainment.

Over 19 million individuals were in attendance at the fair.

Aspects that attracted visitors included the buildings and architecture, new foods, popular music, and exotic people on display. American culture was showcased at the fair especially regarding innovations in communication, medicine, and transportation.

Architects

George Kessler, who designed many urban parks in Texas and the Midwest, created the master design for the Fair.

A popular myth says that

George Kessler, who designed many urban parks in Texas and the Midwest, created the master design for the Fair.

A popular myth says that Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822 – August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, Social criticism, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the U ...

, who had died the year before the Fair, designed the park and fair grounds. There are several reasons for this confusion. First, Kessler in his twenties had worked briefly for Olmsted as a Central Park

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City, and the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the List of parks in New York City, sixth-largest park in the ...

gardener. Second, Olmsted was involved with Forest Park in Queens, New York. Third, Olmsted had planned the renovations in 1897 to the Missouri Botanical Garden

The Missouri Botanical Garden is a botanical garden located at 4344 Shaw Boulevard in St. Louis, Missouri. It is also known informally as Shaw's Garden for founder and philanthropy, philanthropist Henry Shaw (philanthropist), Henry Shaw. I ...

several blocks to the southeast of the park. Finally, Olmsted's sons advised Washington University on integrating the campus with the park across the street.

In 1901, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Corporation selected prominent St. Louis architect Isaac S. Taylor as the Chairman of the Architectural Commission and Director of Works for the fair, supervising the overall design and construction. Taylor quickly appointed Emmanuel Louis Masqueray to be his Chief of Design. In the position for three years, Masqueray designed the following Fair buildings: Palace of Agriculture, the Cascades and Colonnades, Palace of Forestry, Fish, and Game, Palace of Horticulture and Palace of Transportation, all of which were widely emulated in civic projects across the United States as part of the City Beautiful movement

The City Beautiful movement was a reform philosophy of North American architecture and urban planning that flourished during the 1890s and 1900s with the intent of introducing beautification and monumental grandeur in cities. It was a part of th ...

. Masqueray resigned shortly after the Fair opened in 1904, having been invited by Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (often abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 311,527, making it Minnesota's second-most populous city a ...

to design a new cathedral for the city. The Palace of Electricity was designed by Messrs, Walker & Kimball, of Omaha, Nebraska. It covered and cost over $400,000 (equivalent to more than $ in ). Crowning the great towers were heroic groups of statuary typifying the various attributes of electricity.

Board of Commissioners

Florence Hayward, a successful freelance writer in St. Louis in the 1900s, was determined to play a role in the World's Fair. She negotiated a position on the otherwise all-male Board of Commissioners. Hayward learned that one of the potential contractors for the fair was not reputable and warned the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company (LPEC). In exchange for this information, she requested an appointment as roving commissioner to Europe. Former Mayor of St. Louis and Governor of MissouriDavid R. Francis

David Rowland Francis (October 1, 1850January 15, 1927) was an American politician and diplomat. He served in various positions including Mayor of St. Louis, the 27th Governor of Missouri, and United States Secretary of the Interior. He was th ...

, LPEC president, made the appointment and allowed Hayward to travel overseas to promote the fair, especially to women. The fair also had a Board of Lady Managers (BLM) who felt they had jurisdiction over women's activities at the fair and objected to Hayward's appointment without their knowledge. Despite this, Hayward set out for England in 1902. Hayward's most notable contribution to the fair was acquiring gifts Queen Victoria received for her Golden Jubilee and other historical items, including manuscripts from the Vatican. These items were all to be shown in exhibits at the fair.

Pleased with her success in Europe, Francis put her in charge of historical exhibits in the anthropology division, which had originally been assigned to Pierre Chouteau III. Despite being the only woman on the Board of Commissioners, creating successful anthropological exhibits, publicizing the fair, and acquiring significant exhibit items, Hayward's role in the fair was not acknowledged. When Francis published a history of the fair in 1913, he did not mention Hayward's contributions and she never forgave the slight.

Scientific contributions

Many of the inventions displayed were precursors to items which have become an integral part of today's culture. Novel applications of electricity and light waves for communication and medical use were displayed in the Palace of Electricity. According to an article he wrote for Harper's Weekly, W. E. Goldsborough, the Chief of the Department of Electricity for the Fair, wished to educate the public and dispel the misconceptions about electricity which many common people believed. New and updated methods of transportation also showcased at the World's Fair in the Palace of Transportation would come to revolutionize transportation for the modern day.Communication contributions

Wireless telephone – The "wireless telephony" unit or "radiophone

A radiotelephone (or radiophone), abbreviated RT, is a radio communication system for conducting a conversation; radiotelephony means telephony by radio. It is in contrast to ''radiotelegraphy'', which is radio transmission of telegrams (messag ...

" was invented by Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (; born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born Canadian Americans, Canadian-American inventor, scientist, and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He als ...

and installed at the St. Louis World Fair. This radiophone comprised a sound-light transmitter and a light-sound receiver, as an apparatus in the Palace of Electricity transmitted music or speech to a receiver in the courtyard. Visitors heard the transmission when holding the cordless receiver to the ear. It developed into the radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

and telephone.

Early fax machine – The telautograph

The telautograph is an ancestor of the modern fax machine. It transmits electrical signals representing the position of a pen or tracer at the sending station to repeating mechanisms attached to a pen at the receiving station, thus reproducing at ...

was invented in 1888 by American scientist Elisha Gray

Elisha Gray (August 2, 1835 – January 21, 1901) was an American electrical engineering, electrical engineer who co-founded the Western Electric, Western Electric Manufacturing Company. Gray is best known for his Invention of the telephone, dev ...

, who contested Alexander Graham Bell's invention of the telephone. A person wrote on one end of the telautograph, which electrically communicated with the receiving pen to recreate drawings on paper. In 1900, assistant Foster Ritchie improved the device to display at the 1904 World's Fair and market for the next thirty years. This developed into the fax machine

Fax (short for facsimile), sometimes called telecopying or telefax (short for telefacsimile), is the telephonic transmission of scanned printed material (both text and images), normally to a telephone number connected to a printer or other out ...

.

Medical contributions

Finsen light – The Finsen light, invented by Niels Ryberg Finsen, treated tuberculosis luposa. Finsen received the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology in 1903. This pioneeredphototherapy

Light therapy, also called phototherapy or bright light therapy is the exposure to direct sunlight or artificial light at controlled wavelengths in order to treat a variety of medical disorders, including seasonal affective disorder (SAD), circ ...

.

X-ray machine – The X-ray machine

An X-ray machine is a device that uses X-rays for a variety of applications including medicine, X-ray fluorescence, electronic assembly inspection, and measurement of material thickness in manufacturing operations. In medical applications, X-ra ...

was launched at the 1904 World's Fair. German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen

Wilhelm may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* William Charles John Pitcher, costume designer known professionally as "Wilhelm"

* Wilhelm (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

Other uses

* Wilhe ...

discovered X-rays studying electrification of low pressure gas. He X-rayed his wife's hand, capturing her bones and wedding ring to show colleagues. Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

and assistant Clarence Dally recreated the machine. Dally failed to test another X-ray machine at the 1901 World's Fair after President McKinley was assassinated. A perfected X-ray machine was successfully exhibited at the 1904 World's Fair. X-rays are now commonplace in hospitals and airports.

Infant incubator – Although infant incubators were invented in the year 1888 by Drs. Alan M. Thomas and William Champion, adoption was not immediate. To advertise the benefits, incubators containing preterm babies were displayed at the 1897

Events

January

* January 2 – The International Alpha Omicron Pi sorority is founded, in New York City.

* January 4 – A British force is ambushed by Chief Ologbosere, son-in-law of the ruler. This leads to a punitive expedit ...

, 1898

Events

January

* January 1 – New York City annexes land from surrounding counties, creating the City of Greater New York as the world's second largest. The city is geographically divided into five boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queen ...

, 1901, and 1904 World Fairs. These provided immunocompromised neonates a sanitary environment. Each incubator comprised an airtight glass box with a metal frame. Hot forced air thermoregulated the container. Newspapers advertised the incubators with "lives are being preserved by this wonderful method." During the 1904 World Fair, E. M. Bayliss exhibited these devices on The Pike where approximately ten nurses cared for twenty-four neonates. The entrance fee was 25 cents () while the adjoining shop and café offered souvenirs and refreshments. Proceeds totaling $181,632 (equivalent to $ in ) helped fund Bayliss's project. Inconsistent sanitation killed some babies, so glass walls were installed between them and visitors, shielding the infants. These developed into "isolettes" in modern neonatal intensive care units.

Transportation contributions

Electric streetcar – North American street railways from the early 19th century were being introduced to electric street railcars. An electric streetcar on a track demonstrated its speed, acceleration, and braking outside the Palace of Electricity. Many downtown trams today are electric. Personal automobile – The Palace of Transportation displayedautomobiles

A car, or an automobile, is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of cars state that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, peopl ...

and motor cars. The private automobile was revealed here. The automobile display contained 140 models including ones powered by gasoline, steam, and electricity. Inventor Lee de Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

demonstrated a prototype car radio

Vehicle audio is equipment installed in a car or other vehicle to provide in-car entertainment and information for the occupants. Such systems are popularly known as car stereos. Until the 1950s, it consisted of a simple AM radio. Additions si ...

. Four years later, the Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

began producing the affordable Ford Model T

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by the Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927. It is generally regarded as the first mass-affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. Th ...

.

Airplane – The 1904 World's Fair hosted the first "Airship Contest". Stationary air balloons demarcated a time trial

In many racing sports, an sportsperson, athlete (or occasionally a team of athletes) will compete in a time trial (TT) against the clock to secure the fastest time. The format of a time trial can vary, but usually follow a format where each athle ...

with a minimum speed limit of . Nobody won the $100,000 grand prize (equivalent to $ in ). The contest witnessed the first public dirigible

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat ( lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding ...

flight in America. A history of aviation in St. Louis followed, leading to the nickname Flight City.

Legacy

St. Louis' status as an up-and-coming city garnered interest from many reporters and photographers who attended the World's Fair and found its citizens constantly on the "go" and the streets "crowded with activity". One observer remarked that, at this time, St. Louis had more energy in its streets than any other northern city did.Buildings

With more and more people interested in the city, St. Louis government and architects were primarily concerned with their ports and access to the city. The city originating as a trading post, transportation by water was important. It was becoming even more important that the port be open, but efficient for all visitors. It also needed to show off some of the city's flair and excitement, which is why in many photographs one sees photos of St. Louis' skyscrapers in the background. In addition to a functioning port, theEads Bridge

The Eads Bridge is a combined road and railway bridge over the Mississippi River connecting the cities of St. Louis, Missouri, and East St. Louis, Illinois. It is located on the St. Louis riverfront between Laclede's Landing, St. Louis, Lacled ...

was constructed, which was considered one of St. Louis' "sights". At long, it connected Missouri and Illinois, and was the first large-scale application of steel as a structural material.  As with the

As with the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in Chicago from May 5 to October 31, 1893, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The ...

in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

in 1893, all but one of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition's grand, neo-Classical exhibition palaces were temporary structures, designed to last but a year or two. They were built with a material called " staff", a mixture of plaster of Paris

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "re ...

and hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a plant in the botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial and consumable use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest ...

fibers, on a wood frame. As at the Chicago World's Fair, buildings and statues deteriorated during the months of the Fair and had to be patched.

The Administration Building, designed by Cope & Stewardson, is now Brookings Hall, the defining landmark on the campus of Washington University. A similar building was erected at Northwest Missouri State University

Northwest Missouri State University (NW Missouri) is a public university in Maryville, Missouri, United States. It has an enrollment of 9,152 students. Founded in 1905 as a teachers college, its campus is based on the design for Forest Park (St. ...

founded in 1905 in Maryville, Missouri. The grounds' layout was also recreated in Maryville and now is designated as the official Missouri State Arboretum.

The Palace of Fine Art, designed by architect Cass Gilbert

Cass Gilbert (November 24, 1859 – May 17, 1934) was an American architect. An early proponent of Early skyscrapers, skyscrapers, his works include the Woolworth Building, the United States Supreme Court building, the state capitols of Minneso ...

, featured a grand interior sculpture court based on the Roman Baths of Caracalla

The Baths of Caracalla () in Rome, Italy, were the city's second largest Ancient Rome, Roman public baths, or ''thermae'', after the Baths of Diocletian. The baths were likely built between AD 212 (or 211) and 216/217, during the reigns of empero ...

. Standing at the top of Art Hill, it now serves as the home of the St. Louis Art Museum.

Saint Louis Zoological Park

The Saint Louis Zoo, officially known as the Saint Louis Zoological Park, is a zoo in Forest Park in St. Louis, Missouri. It is recognized as a leading zoo in animal management, research, conservation, and education. The zoo is accredited by t ...

, dates to the fair. A Jain temple

A Jain temple, Derasar (Gujarati: દેરાસર) or Basadi (Kannada: ಬಸದಿ) is the place of worship for Jains, the followers of Jainism. Jain architecture is essentially restricted to temples and monasteries, and Jain buildings ge ...

carved out of teak stood within the Indian Pavilion near the Ferris Wheel

A Ferris wheel (also called a big wheel, giant wheel or an observation wheel) is an amusement ride consisting of a rotating upright wheel with multiple passenger-carrying components (commonly referred to as passenger cars, cabins, tubs, gondola ...

. It was dismantled after the exhibition and was reconstructed in Las Vegas at the Castaways hotel. It has recently been reassembled and is now on display at the Jain Center of Southern California at Los Angeles. Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Jefferson County, Alabama, Jefferson County. The population was 200,733 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List ...

's iconic cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

Vulcan statue was first exhibited at the Fair in the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy. Additionally, a plaster reproduction of ''Alma Mater'' at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

by Daniel Chester French

Daniel Chester French (April 20, 1850 – October 7, 1931) was an American sculpture, sculptor in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His works include ''The Minute Man'', an 1874 statue in Concord, Massachusetts, and his Statue of Abr ...

was displayed at the Grand Sculpture Court of the exhibition.

The Missouri State building was the largest of the state buildings, as Missouri was the host state. Though it had sections with marble floors and heating and air conditioning, it was planned to be a temporary structure. However, it burned the night of November 18–19, just eleven days before the Fair was to end. Most interior contents were destroyed, but furniture and much of the Model Library were undamaged. The fair being almost over, the building was not rebuilt. In 1909–10, the current World's Fair Pavilion in Forest Park was built on the site of the Missouri building with profits from the fair.

Festival Hall, designed by

Festival Hall, designed by Cass Gilbert

Cass Gilbert (November 24, 1859 – May 17, 1934) was an American architect. An early proponent of Early skyscrapers, skyscrapers, his works include the Woolworth Building, the United States Supreme Court building, the state capitols of Minneso ...

and used for large-scale musical pageants, contained the largest organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

in the world at the time, built by the Los Angeles Art Organ Company (which went bankrupt as a result). The great organ was debuted by the fair's official organist, Charles Henry Galloway. Though the opening concert was scheduled for the first day of the fair, complications related to its construction resulted in the opening concert being postponed until June 9. After the fair, the organ was placed into storage, and eventually purchased by John Wanamaker

John Wanamaker (July 11, 1838December 12, 1922) was an American merchant and religious, civic and political figure, considered by some to be a proponent of advertising and a "pioneer in marketing". He served as United States Postmaster General ...

for his new Wanamaker's

Wanamaker's was an American department store chain founded in 1861 by John Wanamaker. It was one of the first department stores in the United States, and peaked at 16 locations along the Delaware Valley in the 20th century. Wanamaker's was pur ...

store in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

where it was tripled in size and became known as the Wanamaker Organ. The famous Bronze Eagle in the Wanamaker Store also came from the Fair. It features hundreds of hand-forged bronze feathers and was the centerpiece of one of the many German exhibits. Wanamaker's

Wanamaker's was an American department store chain founded in 1861 by John Wanamaker. It was one of the first department stores in the United States, and peaked at 16 locations along the Delaware Valley in the 20th century. Wanamaker's was pur ...

became a Lord & Taylor

Lord & Taylor was an American department store chain founded in 1826 by Samuel Lord. It had 86 full-line stores in the Northeastern United States at its peak in the 2000s, and 38 locations at the time of its liquidation in 2021. The Lord & Tay ...

store and more recently, a Macy's

Macy's is an American department store chain founded in 1858 by Rowland Hussey Macy. The first store was located in Manhattan on Sixth Avenue between 13th and 14th Streets, south of the present-day flagship store at Herald Square on West 34 ...

store.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, who initiated the Louisiana Purchase, as was the first memorial to the third President. It became the headquarters of the Missouri History Museum

The Missouri History Museum in Forest Park, St. Louis, Missouri, showcases Missouri history. It is operated by the Missouri Historical Society, which was founded in 1866. Museum admission is free through a public subsidy by the Metropolita ...

, and stored the Exposition's records and archives when the Louisiana Purchase Exposition company completed its mission. The building is now home to the Missouri History Museum, and the museum was significantly expanded in 2002–3.

The State of Maine Building, which was a rustic cabin, was transported to Point Lookout, Missouri where it overlooked the White River by sportsmen who formed the Maine Hunting and Fishing Club. In 1915, when the main building at the College of the Ozarks

College of the Ozarks is a Private college, private Christian college in Point Lookout, Missouri, United States. The college has an enrollment of 1,426 and over 30 academic majors in Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science programs.

The colleg ...

in Forsyth, Missouri

Forsyth is a city in Taney County, Missouri, United States. The population was 2,730 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Taney County. The town is part of the Branson micropolitan area. Forsyth is located on Lake Taneycomo on U.S. Ro ...

burned, the school relocated to Point Lookout, where the Maine building was renamed the Dobyns Building in honor of a school president. The Dobyns Building burned in 1930 and the college's signature church was built in its place. In 2004, a replica of the Maine building was built on the campus. The Keeter Center is named for another school president.

The observation tower

An observation tower is a tower used to view events from a long distance and to create a full 360 degree range of vision to conduct long distance observations. Observation towers are usually at least tall and are made from stone, iron, and woo ...

erected by the American DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company was brought to the Fair when it became a hazard near Niagara Falls and needed to be removed because in the wintertime, ice from the fall's mist would form on the steel structure, and eventually fall onto the buildings below. It served as a communications platform for Lee DeForest's work in wireless telegraphy and a platform to view the fair. As Niagara Falls was near Buffalo New York, it was also called the Buffalo Tower After the World's Fair, it was moved to Creve Coeur Lake to be part of that park.

The Swedish Pavilion is still preserved in Lindsborg, Kansas. Designed by Swedish architect

The Swedish Pavilion is still preserved in Lindsborg, Kansas. Designed by Swedish architect Ferdinand Boberg

Gustaf Ferdinand Boberg (11 April 1860 – 7 May 1946) was a Swedish architect.

Biography

Boberg was born in Falun. He became one of the most productive and prominent architects of Stockholm around the turn of the 20th century. Among his most ...

, it is the only one of his international exposition buildings in existence today. After the fair, the Pavilion was moved to Bethany College in Lindsborg, where it was used for classroom, library, museum and department facilities for the art department. In 1969, it was moved to the Lindsborg Old Mill & Swedish Heritage Museum where it serves as a venue for community events. The Pavilion was added to the National Historic Register in 1973.

Westinghouse Electric

The Westinghouse Electric Corporation was an American manufacturing company founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse and headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was originally named "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company" and was ...

sponsored the Westinghouse Auditorium, where they showed films of Westinghouse factories and products.

Some mansions from the Exposition's era survive along Lindell Boulevard at the north border of Forest Park.

Introduction of new foods

A number of foods are claimed to have been invented at the fair. The most popular claim is that of the waffle-styleice cream cone

An ice cream cone (England) or poke (Ireland) is a brittle, cone-shaped pastry, usually made of a wafer similar in texture to a waffle, made so ice cream can be carried and eaten without a bowl or spoon. Many styles of cones are made, includ ...

. However, its popularization, not invention, is widely believed to have taken place here. Dubious claims include the hamburger

A hamburger (or simply a burger) consists of fillings—usually a patty of ground meat, typically beef—placed inside a sliced bun or bread roll. The patties are often served with cheese, lettuce, tomato, onion, pickles, bacon, or chilis ...

and hot dog

A hot dog is a grilled, steamed, or boiled sausage served in the slit of a partially sliced bun. The term ''hot dog'' can also refer to the sausage itself. The sausage used is a wiener ( Vienna sausage) or a frankfurter ( Frankfurter Würs ...

(both traditional American and European foods of German origin), peanut butter

Peanut butter is a food Paste (food), paste or Spread (food), spread made from Grinding (abrasive cutting), ground, dry roasting, dry-roasted peanuts. It commonly contains additional ingredients that modify the taste or texture, such as salt, ...

, iced tea

Iced tea (or ice tea) is a form of cold tea. Though it is usually served in a glass with ice, it can refer to any tea that has been chilled or cooled. It may be sweetened with sugar or syrup, or remain unsweetened. Iced tea is also a popular pac ...

, and cotton candy

Cotton candy, also known as candy floss (candyfloss) and fairy floss, is a spun sugar confection that resembles cotton. It is made by heating and liquefying sugar, and spinning it centrifugally through minute holes, causing it to rapidly cool ...

. Again, popularization is more likely. Dr Pepper

Dr Pepper is a carbonated soft drink. Dr Pepper was created in the 1880s by the American pharmacist Charles Alderton in Waco, Texas, and was first nationally marketed in the United States in 1904. It is manufactured by Keurig Dr Pepper in t ...

and Puffed Wheat cereal were introduced to a national audience. Freeborn Annie Fisher received a gold medal for her beaten biscuits famous in her hometown of Columbia, Missouri

Columbia is a city in Missouri, United States. It was founded in 1821 as the county seat of Boone County, Missouri, Boone County and had a population of 126,254 as recorded in the 2020 United States census, making it the List of cities in Misso ...

. President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

enjoyed them on his 1911 visit to Missouri.

Though not the debut of as many foods as claimed, the fair offered what was essentially America's first food court. Visitors sampled a variety of fast foods, dined in dozens of restaurants, and strolled through the mile-long pike. As one historian said of the fair, "one could breakfast in France, take a mid-morning snack in the Philippines, lunch in Italy, and dine in Japan."

Influence on popular music and literature

The fair inspired the song " Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis", which was recorded by many artists, including Billy Murray. Both the fair and the song are focal points of the 1944 feature film '' Meet Me in St. Louis'' starringJudy Garland

Judy Garland (born Frances Ethel Gumm; June 10, 1922June 22, 1969) was an American actress and singer. Possessing a strong contralto voice, she was celebrated for her emotional depth and versatility across film, stage, and concert performance. ...

, which also inspired a Broadway musical version. Scott Joplin

Scott Joplin (November 24, 1868 – April 1, 1917) was an American composer and pianist. Dubbed the "King of Ragtime", he composed more than 40 ragtime pieces, one ragtime ballet, and two operas. One of his first and most popular pieces, the ...

wrote the rag "Cascades" in honor of the elaborate waterfalls in front of Festival Hall.

A book entitled ''Wild Song'', by Candy Gourlay

Candy Gourlay (née Quimpo) is a Filipino journalist and author based in the United Kingdom whose debut novel ''Tall Story'' (2010) was shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal (literary award), Carnegie Medal.

Biography

Gourlay was born and raised i ...

, was inspired by the Louisiana Purchase.

People on display

Following theSpanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

, the peace treaty

A peace treaty is an treaty, agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually country, countries or governments, which formally ends a declaration of war, state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an ag ...

granted the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

control over Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, and Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

. Puerto Rico had had a quasi-autonomous government as an "overseas province" of Spain, and the Philippines, having declared independence after the 1896–1899 Philippine Revolution

The Philippine Revolution ( or ; or ) was a war of independence waged by the revolutionary organization Katipunan against the Spanish Empire from 1896 to 1898. It was the culmination of the 333-year History of the Philippines (1565–1898), ...

, fought US annexation in the 1899–1902 Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

. These areas controversially became unincorporated territories of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indian reservations i ...

in 1899, and people were brought from these territories to be on "display" at the 1904 fair.

The fair displayed 1,102 Filipinos

Filipinos () are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. Filipinos come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Filipino language, Filipino, Philippine English, English, or other Philippine language ...

, 700 of them Philippine Scouts

The Philippine Scouts ( Filipino: ''Maghahanap ng Pilipinas''/''Hukbong Maghahanap ng Pilipinas'') was a military organization of the United States Army from 1901 until after the end of World War II. These troops were generally Filipinos and ...

and Philippine Constabulary

The Philippine Constabulary (PC; , ''HPP''; ) was a gendarmerie-type military police force of the Philippines from 1901 to 1991, and the predecessor to the Philippine National Police. It was created by the Insular Government, American occupat ...

, used for controlling conflict among Filipinos and between Filipinos and fair organizers. Displays included the Apache

The Apache ( ) are several Southern Athabaskan language-speaking peoples of the Southwestern United States, Southwest, the Southern Plains and Northern Mexico. They are linguistically related to the Navajo. They migrated from the Athabascan ho ...

of the American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

and the Igorots

The indigenous peoples of the Cordillera in northern Luzon, Philippines, often referred to by the exonym Igorot people, or more recently, as the Cordilleran peoples, are an ethnic group composed of nine main ethnolinguistic groups whose domains ...

of the Philippines, both of which peoples were noted as "primitive". Within the Philippine reservation, was a school which was actively teaching Igorot students. At least two Moros

In Greek mythology, Moros /ˈmɔːrɒs/ or Morus /ˈmɔːrəs/ (Ancient Greek: Μόρος means 'doom, fate') is the personified spirit of impending doom, who drives mortals to their deadly fate. It was also said that Moros gave people the abi ...

were photographed while praying at the fair. The Philippine reservation at the exposition cost $1.1 million (equivalent to $ in ) to create and operate. The people had been trafficked under harsh conditions, and many did not survive. Burial plots in two St. Louis cemeteries were prepared in advance. However, traditional burial practices were not allowed. Some of the people to be exhibited died en route or at the fair and their bodies were immediately removed. Funeral rites had to be conducted without the bodies in front of an oblivious public audience of fair attendees. Organizers choreographed ethnographic displays, having customs which marked special occasions restaged day after day.

Similarly, members of the Southeast Alaskan Tlingit

The Tlingit or Lingít ( ) are Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. , they constitute two of the 231 federally recognized List of Alaska Native tribal entities, Tribes of Alaska. Most Tlingit are Alaska Natives; ...

tribe accompanied fourteen totem pole

Totem poles () are monumental carvings found in western Canada and the northwestern United States. They are a type of Northwest Coast art, consisting of poles, posts or pillars, carved with symbols or figures. They are usually made from large t ...

s, two Native houses, and a canoe displayed at the Alaska Exhibit. Mary Knight Benson, a noted Pomo

The Pomo are a Indigenous peoples of California, Native American people of California. Historical Pomo territory in Northern California was large, bordered by the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast to the west, extending inland to ...

basket weaver whose work is curated at the Smithsonian Institution and National Museum of the American Indian

The National Museum of the American Indian is a museum in the United States devoted to the culture of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. It is part of the Smithsonian Institution group of museums and research centers.

The museum has three ...

, attended to demonstrate her basket making skills which are described as astounding. Athletic events such as a basketball tournament were held to demonstrate the success of the Indian Boarding Schools and other assimilation programs. These efforts were confirmed with the Fort Shaw Indian School girls basketball team who were declared "World Champions" after beating every team who faced them in these denominational games.

It has been argued that the "overriding purpose of the fair really centered on an effort to promote America's new role as an overseas imperial power", and that "While the juxtaposition of "modern" and "primitive" buttressed assumptions of racial superiority, representations of Native American and Filipino life created an impression of continuity between westward expansion across the continent and the new overseas empire." Racializing concepts and epithets used domestically were extended to the people of the overseas territories.

Ota Benga, a Congolese Pygmy, was featured at the fair. Later he was held captive at the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York City. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and the largest Metropolis, metropol ...

in New York, then featured in an exhibit on evolution alongside an orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ...

in 1906, but public protest ended that.

In contrast, the Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

pavilion advanced the idea of a modern yet exotic culture unfamiliar to the turn-of-the-century Western world, much as it had during the earlier Chicago World's Fair. The Japanese government spent lavishly: $400,000, plus $50,000 from the Japanese colonial government of Formosa

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The island of Taiwan, formerly known to Westerners as Formosa, has an area of and makes up 99% of the land under ROC control. It lies about across the Taiwan Strait f ...

, with an additional $250,000 coming from Japanese commercial interests and regional governments; all told, this totaled $700,000 (equivalent to $ in ). A garden, set on the hillside south of the Machinery Hall and Engine House, featured a replica of Kyoto's famous Kinkakuji, showing Japan's ancient sophistication, and a Formosa

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The island of Taiwan, formerly known to Westerners as Formosa, has an area of and makes up 99% of the land under ROC control. It lies about across the Taiwan Strait f ...

Mansion and Tea House, showing her modern colonial efforts. A second exhibition, "Fair Japan on the 'Pike'", organized by Kushibiki and Arai, welcomed the public through a large Niōmon-style gate into a realm of geisha-staffed exotic Japanese consumerism.

In 2025, a historical marker was placed in the Wydown-Skinker neighborhood to commemorate the location of the Philippine Village, following years of advocacy by Filipino American

Filipino Americans () are Americans of Filipino ancestry. Filipinos in North America were first documented in the 16th century and other small settlements beginning in the 18th century. Mass migration did not begin until after the end of the Sp ...

artist Janna Añonuevo Langholz.

Exhibits

After the fair was completed, many of the international exhibits were not returned to their country of origin, but were dispersed to museums in the United States. For example, the Philippine exhibits were acquired by the Museum of Natural History at theUniversity of Iowa

The University of Iowa (U of I, UIowa, or Iowa) is a public university, public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized int ...

. The Vulcan statue is today a prominent feature of the Vulcan Park and Museum in Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Jefferson County, Alabama, Jefferson County. The population was 200,733 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List ...

, where it was originally cast.

The

The Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

coordinated the US government exhibits. It featured a blue whale, the first full-cast of a blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

ever created.

The Fair also featured the original "Floatopia". Visitors floated on rafts of all sorts in the tiny Forest Park Lake. Many Floatopias have occurred since, including the infamous San Diego Floatopia of '83 and the Santa Barbara Floatopia that has been happening for years.

One exhibit of note was Beautiful Jim Key, the "educated" Arabian-Hambletonian cross horse in his Silver Horseshoe Pavilion. He was owned by Dr. William Key, an African-American/Native American former slave, who became a respected self-taught veterinarian, and promoted by Albert R. Rogers, who had Jim and Dr. Key on tour for years around the US, helping to establish a humane movement that encouraged people to think of animals as having feelings and thoughts, and not just "brutes". Jim and Dr. Key became national celebrities along the way. Rogers invented highly successful marketing strategies still in use today. Jim Key could add, subtract, use a cash register, spell with blocks, tell time and give opinions on the politics of the day by shaking his head yes or no. Jim thoroughly enjoyed his "act"—he performed more than just tricks and appeared to clearly understand what was going on. Dr. Key's motto was that Jim "was taught by kindness" instead of the whip, which he was indeed.

Daisy E. Nirdlinger's book, ''Althea, or, the children of Rosemont plantation'' (illustrated by Egbert Cadmus (1868–1939)) was adopted by the Commissioners of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition as the official souvenir for young people.

Olympics

The Fair hosted the 1904 Summer Olympic Games, the first Olympics to be held in the United States: the Games had originally been awarded to Chicago, but after St. Louis threatened to hold a rival international competition in the same timeframe, the Games were relocated. Nonetheless, the sporting events, spread out over several months, were overshadowed by the Fair. Due to high travel costs and European tensions arising from the Russo-Japanese War, many European athletes did not attend the Games, nor did the founder of the modern Olympics, BaronPierre de Coubertin

Charles Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin (; born Pierre de Frédy; 1 January 1863 – 2 September 1937), also known as Pierre de Coubertin and Baron de Coubertin, was a French educator and historian, co-founder of the International Olympic ...

.

Bullfight riot

On June 5, 1904, a bullfight scheduled for an arena just north of the fairgrounds, in conjunction with the fair, turned violent when Missouri governorAlexander Monroe Dockery

Alexander Monroe Dockery (February 11, 1845 – December 26, 1926) was an American physician and politician who served as the 30th governor of Missouri from 1901 to 1905. A Democrat, he was a member of the United States House of Represent ...

ordered police to halt the fight in light of Missouri's anti-bullfighting laws. Disgruntled spectators demanded refunds, and when they were turned away, they began throwing stones through the windows of the arena office. While police protected the office, they did not have sufficient numbers to protect the arena, which was burned to the ground by the mob. The exposition fire department responded to the fire, but disruption to the fair was minimal, as the riot took place on a Sunday, when the fair was closed.

Anglo-Boer War Concession

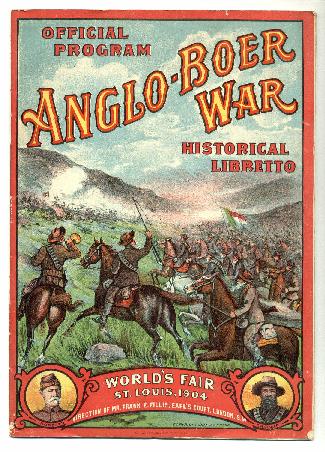

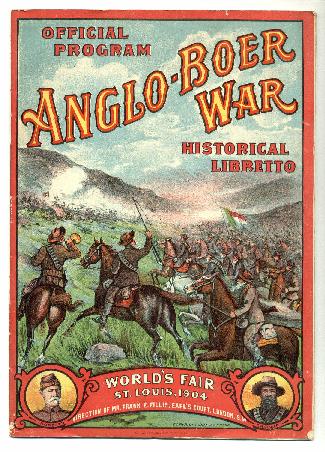

Frank E. Fillis produced what was supposedly "the greatest and most realistic military spectacle known in the history of the world". Different portions of the concession featured a

Frank E. Fillis produced what was supposedly "the greatest and most realistic military spectacle known in the history of the world". Different portions of the concession featured a British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

encampment, several South African native villages (including Zulu, San, Swazi, and Ndebele) and a arena in which soldiers paraded, sporting events and horse races were held and major battles from the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

were re-enacted twice a day. Battle recreations took 2–3 hours and included several generals and 600 veteran soldiers from both sides of the war. At the conclusion of the show, the Boer

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

general Christiaan de Wet

Christiaan Rudolf de Wet (7 October 1854 – 3 February 1922) was a Boer general, rebel leader and politician.

Life

Born on the Leeuwkop farm, in the district of Smithfield in the Boer Republic of the Orange Free State, he later resided at ...

would escape on horseback by leaping from a height of into a pool of water.

Admission ranged from 25 cents () for bleacher seats to one dollar () for box seats, and admission to the villages was another 25 cents. The concession cost $48,000 (equivalent to $ in ) to construct, grossed over $630,000 (equivalent to $ in ), and netted about $113,000 (equivalent to $ in ) to the fair—the highest-grossing military concession of the fair.

Notable attendees

The Louisiana World's Fair was opened by President,

The Louisiana World's Fair was opened by President, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, by telegraph, but he did not attend personally until after his reelection in November 1904, as he stated he did not wish to use the fair for political purposes. Attendees included John Philip Sousa

John Philip Sousa ( , ; November 6, 1854 – March 6, 1932) was an American composer and conductor of the late Romantic music, Romantic era known primarily for American military March (music), marches. He is known as "The March King" or th ...

, a musician, composer and conductor whose band performed on opening day and several times during the fair. Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

is claimed to have attended.

Ragtime

Ragtime, also spelled rag-time or rag time, is a musical style that had its peak from the 1890s to 1910s. Its cardinal trait is its Syncopation, syncopated or "ragged" rhythm. Ragtime was popularized during the early 20th century by composers ...

music was popularly featured at the Fair. Scott Joplin

Scott Joplin (November 24, 1868 – April 1, 1917) was an American composer and pianist. Dubbed the "King of Ragtime", he composed more than 40 ragtime pieces, one ragtime ballet, and two operas. One of his first and most popular pieces, the ...

wrote "The Cascades" specifically for the fair, inspired by the waterfalls at the Grand Basin, and presumably attended the fair.

Helen Keller

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880 – June 1, 1968) was an American author, disability rights advocate, political activist and lecturer. Born in West Tuscumbia, Alabama, she lost her sight and her hearing after a bout of illness when ...

, who was 24 and graduated from Radcliffe College

Radcliffe College was a Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that was founded in 1879. In 1999, it was fully incorporated into Harvard Colle ...

, gave a lecture in the main auditorium.

J. T. Stinson, a well-regarded fruit specialist, introduced the phrase "An apple a day keeps the doctor away

"An apple a day keeps the doctor away" is a common English-language proverb that appeared in the 19th century, advocating for the consumption of apples, and by extension, "if one eats healthful foods, one will remain in good health and will not nee ...

" (at a lecture during the exhibition).

The French organist Alexandre Guilmant played a series of 40 recitals from memory on the great organ in Festival Hall, then the largest pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurised air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a Musical keyboard, keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single tone and pitch, the pipes are provide ...

in the world, including ''Toccata in D minor'' (Op. 108, No. 1) by Albert Renaud, which Renaud had dedicated to Guilmant.

Geronimo

Gerónimo (, ; June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a military leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache bands the Tchihen ...

, the former war chief of the Apache

The Apache ( ) are several Southern Athabaskan language-speaking peoples of the Southwestern United States, Southwest, the Southern Plains and Northern Mexico. They are linguistically related to the Navajo. They migrated from the Athabascan ho ...

, was "on display" in a teepee in the Ethnology Exhibit.

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

, the 22nd and 24th president, attended the opening ceremony on April 30 and "overshadowed President Roosevelt in popular applause, when both stood on the same platform."

Henri Poincaré

Jules Henri Poincaré (, ; ; 29 April 185417 July 1912) was a French mathematician, Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosophy of science, philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathemati ...

gave a keynote address on mathematical physics

Mathematical physics is the development of mathematics, mathematical methods for application to problems in physics. The ''Journal of Mathematical Physics'' defines the field as "the application of mathematics to problems in physics and the de ...

, including an outline for what would eventually become known as special relativity

In physics, the special theory of relativity, or special relativity for short, is a scientific theory of the relationship between Spacetime, space and time. In Albert Einstein's 1905 paper, Annus Mirabilis papers#Special relativity,

"On the Ele ...

.

Jelly Roll Morton

Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe ( Lemott, later Morton; c. September 20, 1890 – July 10, 1941), known professionally as Jelly Roll Morton, was an American blues and jazz pianist, bandleader, and composer of Louisiana Creole descent. Morton was jazz ...

did not visit, stating in his later Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

interview and recordings that he expected jazz pianist Tony Jackson would attend and win a jazz piano competition at the Exposition. Morton said he was "quite disgusted" to later learn that Jackson had not attended either, and that the competition had been won instead by Alfred Wilson; Morton considered himself a better pianist than Wilson.

The poet T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biography''. New York: Oxford University ...

, who was born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri, visited the Igorot Village held in the Philippine Exposition section of the St. Louis World's Fair. Several months after the closing of the World's Fair, he published a short story entitled "The Man Who Was King" in the school magazine of Smith Academy, St. Louis, Missouri, where he was a student. Inspired by the ganza dance that the Igorot people presented regularly in the Village and their reaction to "civilization", the poet explored the interaction of a white man with the island culture. All this predates the poet's delving into the anthropological studies during his Harvard graduate years.

Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economy, political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sc ...

visited upon first coming to the United States in hopes of using some of his findings for a case study on capitalism.

Jack Daniel, the American distiller and the founder of Jack Daniel's Tennessee whiskey distillery, entered his Tennessee whiskey into the World's Fair whiskey competition. After four hours of deliberation, the eight judges awarded Jack Daniel's Tennessee Whiskey the Gold Medal for the finest whiskey in the world. The award was a boon for the Jack Daniel's distillery.

Novelist Kate Chopin

Kate Chopin (, also ; born Katherine O'Flaherty; February 8, 1850 – August 22, 1904) was an American author of short stories and novels based in Louisiana. She is considered by scholars to have been a forerunner of American 20th-century feminis ...

lived nearby and purchased a season ticket to the fair. After her visit on the hot day of August 20, she suffered a brain hemorrhage

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

and died two days later, on August 22, 1904.

Philadelphia mercantilist, John Wanamaker

John Wanamaker (July 11, 1838December 12, 1922) was an American merchant and religious, civic and political figure, considered by some to be a proponent of advertising and a "pioneer in marketing". He served as United States Postmaster General ...

, visited the exposition in November 1904 and purchased an entire collection of German furniture which included the giant ''jugendstil'' brass sculpture of an eagle that he would display in the rotunda of his Wanamaker's department store in Philadelphia. In 1909 Wanamaker also purchased the organ from the fair, which at the time was the biggest pipe organ in the world. It is still featured today, much enlarged, as the Wanamaker Organ in the Grand Court of his Philadelphia retail palace. Wanamaker purchased and donated an ancient Egyptian tomb, a mummy and other relics to the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania.

Benedictine monk, artist and museum founder, Fr. Gregory Gerrer, OSB, exhibited his recent portrait of Pope Pius X

Pope Pius X (; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing Modernism in the Catholic Church, modern ...

at the fair. Following the fair, Gerrer brought the painting to Shawnee, Oklahoma

Shawnee () is a city in and the county seat of Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma, Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 29,857 in 2010, a 4.9 percent increase from the figure of 28,692 in 2000. The city is part of the Oklah ...

, where it is now on display at the Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art

The Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art is a non-profit art museum in Shawnee, Oklahoma, USA. It is located on the former Oklahoma Baptist University Green Campus, being the campus of the former St. Gregory's University. In June 2024, over six years si ...

.

John McCormack, Irish tenor

A tenor is a type of male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. Composers typically write music for this voice in the range from the second B below m ...

, was brought to the fair by James A. Reardon, who was in charge of the Irish exhibit.

The Sundance Kid

Harry Alonzo Longabaugh (1867 – November 7, 1908), better known as the Sundance Kid, was an outlaw and member of Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch in the American Old West. He likely met Butch Cassidy (real name Robert LeRoy Parker) during a hunti ...

visited the exposition, accompanied by Etta Place

Etta Place ( , ?) was a companion of the American outlaws Robert LeRoy Parker, alias Butch Cassidy, and Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, alias Sundance Kid. The three were members of the outlaw gang known as Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch. She was princi ...

.

Commemoration

In conjunction with the Exposition the US Post Office issued a series of five commemorative stamps celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase. The 1-cent value portrays Robert Livingston, the ambassador who negotiated the purchase with France; the 2-cent value depictsThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, who executed the purchase; the 3-cent honors James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American Founding Father of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as presiden ...

, who participated in negotiations with the French; the 5-cent memorializes William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

, who was involved with early plans for the Exposition; and the 10-cent presents a map of the Louisiana Purchase.

See also

* Swedish Pavilion from the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair *1904 Summer Olympics

The 1904 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the III Olympiad and also known as St. Louis 1904) were an international multi-sport event held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from 1 July to 23 November 1904. Many events were conducted ...

* Central West End, St. Louis

* Forest Park

* '' Meet Me in St. Louis''

* Saint Louis Exposition (1884)

* St. Louis, Missouri