St Giles in the Fields is the

Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

of the

St Giles

Saint Giles (, , , , ; 650 - 710), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 7th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly legendary. A ...

district of

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. The parish stands within the

London Borough of Camden

The London Borough of Camden () is a London boroughs, borough in Inner London, England. Camden Town Hall, on Euston Road, lies north of Charing Cross. The borough was established on 1 April 1965 from the former Metropolitan boroughs of the Cou ...

and forms part of the

Diocese of London

The Diocese of London forms part of the Church of England's Province of Canterbury in England.

It lies directly north of the Thames, covering and all or part of 17 London boroughs. This corresponds almost exactly to the historic county of ...

. The church, named for

St Giles the Hermit, began as the chapel of a 12th-century

monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

and

leper hospital

A leper colony, also known by many other names, is an isolated community for the quarantining and treatment of lepers, people suffering from leprosy.

'' M. leprae'', the bacterium responsible for leprosy, is believed to have spread from East ...

in the fields between

Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

and the

City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

and now gives its name to the surrounding urban district of

St Giles

Saint Giles (, , , , ; 650 - 710), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 7th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly legendary. A ...

in the

West End of London, situated between

Seven Dials,

Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, part of the London Borough of Camden in England. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural institution, cultural, intellectual, and educational ...

,

Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

and

Soho

SoHo, short for "South of Houston Street, Houston Street", is a neighborhood in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Since the 1970s, the neighborhood has been the location of many artists' lofts and art galleries, art installations such as The Wall ...

. The present church is the third on the site since 1101 and was rebuilt most recently in 1731–1733 in

Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

style to designs by the architect

Henry Flitcroft

Henry Flitcroft (30 August 1697 – 25 February 1769) was a major English architect in the second generation of Palladianism. He came from a humble background; his father was a labourer in the gardens at Hampton Court. Flitcroft began his career a ...

.

History

12th–16th centuries

Hospital and chapel

The first recorded church on the site was a

chapel

A chapel (from , a diminutive of ''cappa'', meaning "little cape") is a Christianity, Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. First, smaller spaces inside a church that have their o ...

of the

Parish of Holborn attached to a monastery and leper hospital founded by

Matilda of Scotland

Matilda of Scotland (originally christened Edith, 1080 – 1 May 1118), also known as Good Queen Maud, was Queen consort of England and Duchess of Normandy as the first wife of King Henry I. She acted as regent of England on several occasions ...

, "Good Queen Maud", consort of

Henry I Henry I or Henri I may refer to:

:''In chronological order''

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry ...

between the years 1101 and 1109.

The foundation would later become attached as a "cell," or subordinate house, to the larger Hospital of the Lazar Brothers at

Burton Lazars

Burton Lazars is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Burton and Dalby, in the Borough of Melton, Melton district, in the county of Leicestershire, England. It is south-east of Melton Mowbray, having a population of c.450 in ...

, in

Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire to the north, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire to the south-east, Warw ...

.

At the time of its founding it stood well outside the

City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

and distant from the Royal

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster is the meeting place of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and is located in London, England. It is commonly called the Houses of Parliament after the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two legislative ch ...

, on the

main road

A "main road" may refer to:

* A major road in a town or village, or in a country area.

* A highway

* A trunk road, especially in British English

Main Road may refer to:

* Main Road, Hobart, Australia

* Main Road, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh

* Main ...

to

Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in London, Middlesex, England, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone. Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne ...

and

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

. Between 1169 and 1189, on

Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in many Western Christian liturgical calendars on 29 Se ...

,

Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

granted the Hospital the lands, gifts and privileges that were to secure its future. For this he has been credited as a 'second founder'.

The chapel probably began to function as the church of a

hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

that grew up round the hospital. Although there is no record of any presentation to the

living

Living or The Living may refer to:

Common meanings

*Life, a condition that distinguishes organisms from inorganic objects and dead organisms

** Living species, one that is not extinct

*Personal life, the course of an individual human's life

* ...

before the hospital was

suppressed in 1539, the fact that the

parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

of St. Giles was in existence at least as early as 1222 means that the church was at least partially used for parochial purposes from that time.

The Precinct of the Hospital probably included the whole of the island site now bounded by High Street,

Charing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street), which then merges into Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direc ...

and

Shaftesbury Avenue

Shaftesbury Avenue is a major road in the West End of London, named after The 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. It runs north-easterly from Piccadilly Circus to New Oxford Street, crossing Charing Cross Road at Cambridge Circus. From Piccadill ...

. As well as the Hospital church which stood on the site of the present St Giles there would have been other buildings connected to the hospital including the Master's House (subsequently called the Mansion House) to the west of the church, and the 'Spittle Houses', dwellings attached to the Hospital on the eastern end of the present churchyard including the Angel Inn, which remains on the same site.

St Giles's position halfway between the ancient cities of

Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

and

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

is perhaps no coincidence. As

George Walter Thornbury

George Walter Thornbury (13 November 1828 – 11 June 1876) was an English author. He was the first biographer of J. M. W. Turner.

Early life

George Thornbury was born on 13 November 1828, the son of a London solicitor, reared by his aunt and e ...

noted in London Old & New "it is remarkable that in almost every ancient town in England, the church of St. Giles stands either outside the walls, or, at all events, near its outlying parts, in allusion, doubtless, to the arrangements of the Israelites of old, who placed their lepers outside the camp."

Under the Lazar brothers

During the 13th century a Papal Bull confirmed the hospital's privileges and granted it special protection under the

See of Rome

See or SEE may refer to:

* Visual perception

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Music:

** ''See'' (album), studio album by rock band The Rascals

*** "See", song by The Rascals, on the album ''See''

** "See" (Tycho song), song by Tycho

* Televisio ...

.

The

Papal Bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

reveals that the lepers were trying to live as a

religious community Religious community may refer to:

* Church (congregation), a religious organization or congregation that meets in a particular location

* Confessional community, a group of people with similar religious beliefs

* Institute of consecrated life, a ...

and that the Hospital precinct included gardens and 8 acres of land adjoining the Hospital to the north and south. The hospital was supported by the Crown and administered by the City of London for its first 200 years, being known as a

Royal Peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch.

Definition

The church parish system dates from the ea ...

.

In 1299,

Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

assigned it to

Hospital of Burton Lazars in

Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire to the north, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire to the south-east, Warw ...

, a house of the order of

St. Lazarus of Jerusalem, a

chivalric order

An order of chivalry, order of knighthood, chivalric order, or equestrian order is a society, fellowship and college of knights, typically founded during or inspired by the original Catholic military orders of the Crusades ( 1099–1291) and pai ...

from the era of the

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

.

The 14th century was turbulent for the hospital, with frequent accusations of corruption and mismanagement from the City and Crown authorities and suggestions that members of the Order of Saint Lazarus (known as ''Lazar brothers)'' put the affairs of the monastery ahead of caring for the lepers.

In 1348 The Citizens contended to the King that since the Master and brothers of Burton Lazars had taken over St. Giles's the friars had ousted the lepers and replaced them by brothers and sisters of the Order of St. Lazarus, who were not diseased and ought not to associate with those who were.

The Hospital appears to have been governed by a Warden, who was subordinate to the Master of Burton Lazars. The King intervened on several occasions and appointed a new head of the hospital.

Eventually, in 1391,

Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Joan, Countess of Kent. R ...

sold the hospital, chapel and lands to the

Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

abbey of

St Mary de Graces by the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

. This was opposed by the Lazars and their new Master, Walter Lynton, who responded by leading a group of armed men to St Giles, recapturing it by force

and by the City of London, which withheld rent money in protest.

During this occupation the Order of St Lazarus opposed with armed force a visitation by the

Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

and many important documents and records were lost or destroyed.

The dispute was finally settled peacefully in court with the King claiming he had been misled about the ownership of St Giles and recognising Lynton as legal 'Master of St Giles Hospital' and the Hospital of Burton Lazarus

with the Cistercian sale being formally revoked in 1402 and the property returned to the Lazar Brothers.

The property at the time included of farmland and a survey-enumerated eight horses, twelve oxen, two cows, 156 pigs, 60 geese and 186 domestic fowl.

Lepers were cared for there until the mid-16th century, when the disease abated and the monastery took to caring for indigents instead.

The Precinct of the Hospital probably included the whole of the site now bounded by

St Giles High Street

St Giles is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Camden. It is in Central London and part of the West End. The area gets its name from the parish church of St Giles in the Fields. The combined parishes of St Gile ...

,

Charing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street), which then merges into Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direc ...

and

Shaftesbury Avenue

Shaftesbury Avenue is a major road in the West End of London, named after The 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. It runs north-easterly from Piccadilly Circus to New Oxford Street, crossing Charing Cross Road at Cambridge Circus. From Piccadill ...

; it was entered by a

Gatehouse

A gatehouse is a type of fortified gateway, an entry control point building, enclosing or accompanying a gateway for a town, religious house, castle, manor house, or other fortification building of importance. Gatehouses are typically the most ...

in St Giles High Street.

Lollardy and Oldcastle's Rising

In 1414, St Giles Fields served as the centre of

Sir John Oldcastle

''Sir John Oldcastle'' is an Elizabethan play about John Oldcastle, a controversial 14th-/15th-century rebel and Lollard who was seen by some of Shakespeare's contemporaries as a proto-Protestant martyr.

Publication

The play was originally ...

's abortive proto-Protestant

Lollard uprising directed against the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and the English king Henry V. In anticipation of

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

, Lollard beliefs were outlined in the 1395

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards which dealt with, among other things, their opposition to

capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

, rejection of

religious celibacy and belief that members of the

clergy should be held accountable to civil laws. Rebel

Lollards

Lollardy was a proto-Protestantism, proto-Protestant Christianity, Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic C ...

answered a summons to assemble among the 'dark thickets'

by St. Giles's Fields on the night of

Jan. 9, 1414. The King, however, was forewarned by his agents and the small group of

Lollards

Lollardy was a proto-Protestantism, proto-Protestant Christianity, Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic C ...

in assembly were captured or dispersed. The rebellion brought severe reprisals and marked the end of the

Lollards' overt political influence after many of the captured rebels were brutally executed. Of their number, 38 were

dragged on hurdles through the streets from

Newgate

Newgate was one of the historic seven gates of the London Wall around the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. Newgate lay on the west side of the wall and the road issuing from it headed over the River Fleet to Mid ...

to St Giles on January 12 and hanged side by side in batches of four while the bodies of the seven who had been formally condemned as

heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

by the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

were burned afterwards. Four more were hanged a week later. Finally, on 14 December 1417

Sir John Oldcastle

''Sir John Oldcastle'' is an Elizabethan play about John Oldcastle, a controversial 14th-/15th-century rebel and Lollard who was seen by some of Shakespeare's contemporaries as a proto-Protestant martyr.

Publication

The play was originally ...

himself was

hanged in chains

Gibbeting is the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of criminals were hanged on public display to deter other existing or potential criminals. Occasionally, the gibbet () was also used as a method of public exec ...

and

burnt 'gallows and all' in St Giles Fields.

The famous scene of the meeting of the Lollards at St Giles Fields was later memorialised by

Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (; 6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of ...

in his poem ''Sir John Oldcastle, Lord Cobham'':

16th century dissolution and decay.

Dissolution of the Hospital of St Giles and the first parish church

Under the reign

Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

, in 1536, the hospital's ownership of certain parcels of land was disputed by the King's commissioners and as a result it was stripped of almost all the lands gifted by parishioners and benefactors since its foundation. This included over 45 acres of St Giles Parish itself

and the avowdson of the ancient parish of St Dunstan's

Feltham

Feltham () is a town in West London, England, from Charing Cross. Historically part of Middlesex, it became part of the London Borough of Hounslow in 1965. The parliamentary constituency of Feltham and Heston (UK Parliament constituency), Felt ...

, which was among the earliest gifts to the Hospital

which were all handed over to the Crown. All this, however, merely anticipated the momentous events of 1544 when the entire hospital, along with the Hospital of Burton St Lazar, was finally

dissolved with all the Hospital lands, rights and privileges, excluding the chapel, being granted to the king

John Dudley, Lord Lisle in 1548.

The chapel survived as the local parish church, the first

Rector of St Giles being appointed in 1547 when the phrase "in the fields" was first added to the name to distinguish it from St Giles Cripplegate.

Perhaps nothing remains of the medieval church of St Giles however we can reconstruct something of its appearance from the historical record.

According to an order of the Vestry of 8 August 1623, the medieval parish church stood 153 feet by 65 feet and consisted of a nave and a chancel, both with pillars and clerestory walls above and with aisles on either side. in the 46th year of Henry III or 1262 there is a record of a bequest by Robert of Portpool to the Hospital chapel providing for the maintenance of a chaplain "to celebrate perpetually divine service in the chapel of St. Michael within the hospital church of S. Giles.". Thus we may surmise that the church building was of a tripartite structure likely consisting of side aisles supported on rounded Norman arches and lit by clerestory windows above, leading to separate chapels dedicated to St Michael and St Giles on either side of the central nave which lead to a chancel separated from the body of the church by a rood screen.

There is a further indication, in the Vestry minutes of 21 April 1617, that there was a sort of round tower,

spirelet or conical bell turret at the western end of the structure.

Intriguingly, the other remaining medieval relic of the order of

St. Lazarus of Jerusalem in England, the 12th-century Church of St James, which now serves as the parish church of

Burton Lazars

Burton Lazars is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Burton and Dalby, in the Borough of Melton, Melton district, in the county of Leicestershire, England. It is south-east of Melton Mowbray, having a population of c.450 in ...

,

Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire to the north, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire to the south-east, Warw ...

, appears quite closely to resemble the description of what St Giles may have looked like in its medieval state.

The Babington Plot

140 years after Oldcastle's rising, St Giles was the scene of another act of public treason when it played host to the

Babington Plot

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestantism, Protestant, and put Mary, Queen of Scots, her Catholic Church, Catholic cousin, on the English throne. It led to Mary's execution, a result of a letter s ...

.

The issuance of the

papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

''

Regnans in Excelsis

''Regnans in Excelsis'' ("Reigning on High") is a papal bull that Pope Pius V issued on 25 February 1570. It excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England, referring to her as "the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime," declared h ...

'' by

Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V, OP (; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (and from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 January 1566 to his death, in May 1572. He was an ...

on 25 February 1570 had granted English Catholics licence to overthrow the

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

English queen and in 1585 a cell of

recusants

Recusancy (from ) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign of Elizabeth I, and temporarily repea ...

,

crypto-Catholics and

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priests hatched a plan in the precincts of St Giles to murder

Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

and invite a Spanish invasion of England with the purpose of replacing her with Catholic

Queen Mary.

The chief conspirators in the plot were

Anthony Babington

Anthony Babington (24 October 156120 September 1586) was an English gentleman convicted of plotting the assassination of Elizabeth I of England and conspiring with the imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots, for which he was hanged, drawn and quartered ...

and

John Ballard. Babington, a young gentleman of

Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

, was recruited by Ballard, a

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest and Roman Catholic missionary who hoped to do away with the 'heretic' Queen Elizabeth and rescue the Scottish Queen Mary from her imprisonment at

Fotheringhay Castle

Fotheringhay Castle, also known as Fotheringay Castle, was a High Middle Age Norman Motte-and-bailey castle in the village of Fotheringhay to the north of the market town of Oundle, Northamptonshire, England (). It was probably founded ar ...

.

The plot was quickly uncovered by Queen Elizabeth's spymaster

Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her " spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wa ...

and used by him as a means to entrap Mary. The plan was conceived in talks in held at St Giles's Fields and the taverns of the parish and thus, when the plot was finally exposed, the conspirators were returned to St Giles churchyard to be

hanged, drawn, and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was a method of torturous capital punishment used principally to execute men convicted of high treason in medieval and early modern Britain and Ireland. The convicted traitor was fastened by the feet to a h ...

.

Ballard and Babington were executed on 20 September 1586 along with the other men who had been tried with them. Such was the public outcry at the horror of their execution that Elizabeth changed the order for the second group to be allowed to hang until "quite dead" before disembowelling and quartering.

The fact that Babington had solicited a letter from Mary Queen of Scots expressing tacit approval for the plot led to her execution on 8 February 1587.

The exposure of the plot and the role of the Catholic church in fomenting rebellion was to stoke anti-Catholic reaction in the century to come.

17th century, Civil War, Restoration and Plague.

Duchess Dudley's church

By the second decade of the 17th century, the medieval church had suffered a series of collapses, and the parishioners decided to erect a new church, which was begun 1623 and completed in 1630.

It was consecrated on 26 January 1630. mostly paid for by the

Duchess of Dudley, wife of

Sir Robert Dudley.

The 'poor players of

The Cockpit The Cockpit can refer to:

* Cockpit Theatre, a 17th-century theatre in London (also known as the Phoenix) that opened in 1616

* The Cockpit, a theatre in London, England that opened in 1970

* ''The Cockpit'' (OVA), a three-part anime series made ...

theatre' were also said to have contributed a sum of £20 towards the new church building.

The new church was handsomely appointed and sumptuously furnished. 123 feet long and the breadth 57 wide with a steeple in rubbed brick, galleries adorning the north and south aisles with a great east window of

coloured and painted glass.

The new building was consecrated by

William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I of England, Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Caroline era#Religion, Charles I's religious re ...

,

Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

.

An illuminated list of subscribers to the rebuilding is still kept in the church.

Civil War and sectarian conflict

The ruptures in church and state which would eventually lead to the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

were felt early in St Giles Parish. In 1628 the first rector of the newly consecrated church,

Roger Maynwaring

Roger Maynwaring (variously spelled Mainwaring or Manwaring; – 29 June 1653) was an English bishop in the Church of England. He was censured by Parliament in 1628 for sermons perceived as undermining the law and constitution.

Although his ex ...

was fined and deprived of his clerical functions by order of Parliament after two

sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present context ...

s, given on 4 May, which were considered to have impugned the rights of Parliament and advocated for the

Divine Right of the

Stuart Kings.

The controversy would be continued into the 1630s when

Archbishop Laud's former chaplain, William Heywood, was installed as Rector. It was Heywood, under Laud's patronage, who began to ornament and decorate St Giles in the

High Church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

,

Laudian

Laudianism, also called Old High Churchmanship, or Orthodox Anglicanism as they styled themselves when debating the Tractarians, was an early seventeenth-century reform movement within the Church of England that tried to avoid the extremes of Rom ...

fashion and to alter the ceremonial of the sacraments. This provoked the Protestant (particularly

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

) parishioners of St Giles to present Parliament with a petition listing and enumerating the 'popish reliques' with which Heywood had set up 'at needless expense to the parish'

as well as the 'Superstitious and Idolatrous manner of administration of the Sacrament of the Lords Supper'.

The offending ceremonial was closely described by the parishioners in their complaint to parliament:

''"They

he Clergyenter into the Sanctum Sanctorum in which place they reade their second Service, and it is divided into three parts, which is acted by them all three, with change of place, and many duckings before the Altar, with divers Tones in their Voyces, high and low, with many strange actions by their hands, now up then downe, This being ended, the Doctor takes the Cups from the Altar and delivers them to one of the Subdeacons who placeth' them upon a side Table, Then the Doctor kneeleth to the Altar, but what he doth we know not, nor what hee meaneth by it. . .

''

At this time the interior was heavily furnished by Heywood and provided with numerous

ornaments

An ornament is something used for decoration.

Ornament may also refer to:

Decoration

*Ornament (art), any purely decorative element in architecture and the decorative arts

*Ornamental turning

*Biological ornament, a characteristic of animals tha ...

, many of which were the gift of

Alice Dudley, Duchess of Dudley. Chief among them was an elaborate

screen of carved oak placed where one had formerly stood in the medieval church. This, as described in the petition to Parliament in 1640, was "in the figure of a beautiful gate, in which is carved two large pillars, and three large statues: on the one side is

Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

, with his sword; on the other

Barnabas

Barnabas (; ; ), born Joseph () or Joses (), was according to tradition an early Christians, Christian, one of the prominent Disciple (Christianity), Christian disciples in Jerusalem. According to Acts 4:36, Barnabas was a Cypriot Jews, Cyprio ...

, with his book; and over them

Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

with his keyes. They are all set above with winged

cherub

A cherub (; : cherubim; ''kərūḇ'', pl. ''kərūḇīm'') is one type of supernatural being in the Abrahamic religions. The numerous depictions of cherubim assign to them many different roles, such as protecting the entrance of the Garden of ...

ims, and beneath supported by lions."Elaborate and expensive

altar rail

The altar rail (also known as a communion rail or chancel rail) is a low barrier, sometimes ornate and usually made of stone, wood or metal in some combination, delimiting the chancel or the sanctuary and altar in a church, from the nave and ot ...

s would have separated the

altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religion, religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, Church (building), churches, and other places of worship. They are use ...

from congregation. This ornamental balustrade extended the full width of the

chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

and stood 7 or 8 feet east of the screen at the top of three steps while the altar stood close up to the east wall paved with marble.

The result of the parishioners' petition to Parliament was that most of the ornaments were stripped and sold in 1643, while Lady Dudley was still alive.

Dr Heywood was still the incumbent at the time of the outbreak of the

English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

in 1642. As well as Rector of St Giles he had, of course, been a domestic chaplain to

Archbishop Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms; he was arrested by Parliament in 164 ...

, chaplain in ordinary to

King Charles I and

prebendary

A prebendary is a member of the Catholic Church, Catholic or Anglicanism , Anglican clergy, a form of canon (priest) , canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in part ...

at

St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

. All this marked him out for special attention after the execution of the King and during the

Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

period he was imprisoned and suffered many hardships.

Heywood was forced to flee London, residing in

Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

until the

Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 when he was finally re-instated to the living of St Giles.

In 1645 the parish notes record the erection of a copy of the

Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August ...

in the nave of the church and in 1650, a year after the

execution of the King, with the fall of the monarchy seemingly irreversibly settled, an order was given for the 'taking down of the Kings Arms' in the church and the clear-glazing of the windows in the nave.

Following the interregnum, in 1660,

Charles II was

rapturously received back into London and the bells of St Giles were pealed for three days.

Royalism

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gover ...

was at its highest pitch.

William Heywood was reinstated to his living at St Giles for a short period before being succeeded by the

Dr Robert Boreman, previously

Clerk of the Green Cloth

The Clerk of the Green Cloth was a position in the British Royal Household. The clerk acted as secretary of the Board of Green Cloth, and was therefore responsible for organising royal journeys and assisting in the administration of the Royal H ...

to

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

and a fellow deprived Royalist. Revd. Boreman is remembered best for his bitter exchange with

Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter (12 November 1615 – 8 December 1691) was an English Nonconformist (Protestantism), Nonconformist church leader and theologian from Rowton, Shropshire, who has been described as "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". He ma ...

the

Nonconformist leader and occasional parishioner of St Giles.

Revd. John Sharp and the Glorious Revolution

In 1675

Dr. John Sharp was appointed to the position of Rector by the influence and patronage of

Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham

Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham, Privy Council of England, PC (23 December 162018 December 1682), Lord Chancellor of England, was descended from the old family of Earl of Winchilsea, Finch, many of whose members had attained high legal emi ...

and

Lord Keeper of the Great Seal

The Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England, and later of Great Britain, was formerly an officer of the English Crown charged with physical custody of the Great Seal of England. This position evolved into that of one of the Great Officers of ...

. Sharp's father had been a prominent

Bradford

Bradford is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in West Yorkshire, England. It became a municipal borough in 1847, received a city charter in 1897 and, since the Local Government Act 1972, 1974 reform, the city status in the United Kingdo ...

ian

puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

who enjoyed the favour of

Thomas Fairfax

Sir Thomas Fairfax (17 January 1612 – 12 November 1671) was an English army officer and politician who commanded the New Model Army from 1645 to 1650 during the English Civil War. Because of his dark hair, he was known as "Black Tom" to his l ...

and inculcated him in

Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

,

Low Church

In Anglican Christianity, the term ''low church'' refers to those who give little emphasis to ritual, often having an emphasis on preaching, individual salvation, and personal conversion. The term is most often used in a liturgical sense, denot ...

, doctrines, while his mother, being strong

Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

, instructed him in the liturgy of the

Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

. Thus he could be seen as bridging the divide within the reformed religion in England.

Sharp became deeply committed to his ministry at St Giles and indeed later declined the more profitable benefice of

St Martin in the Fields so as to continue ministering to the poor and turbulent parish of St Giles.

[ ]

The Rector would spend the next sixteen years reforming and reconstituting the parish from the disorder of the post-civil-war period. He

preached regularly (at least twice every Sunday at St Giles as well as weekly in other city churches) and with "much fluency, piety

ndgravity", becoming, according to

Bishop Burnet "one of the most popular preachers of the age". Sharp completely re-ordered the system of worship at St Giles around the Established Liturgy of the

Book Of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

, a liturgy he considered "almost perfectly designed".

He instituted, perhaps for the first time, a weekly

Holy Communion

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an ordinance in others. Christians believe that the rite was instituted by J ...

and restored the

Daily Offices in the church.

Sharp also insisted upon communicants kneeling to receive communion.

In the wider parish he was constant in his

catechising of young people and in performing

visitations of the sick, often at the hazard of his own life. Somehow he avoided serious illness despite "bear

nghis share of duty among the cellars and the garrets"

of a district already synonymous with plague and sickness. Indeed, his solicitude for his parishioners left him at risk in many ways. He once survived an attempted assassination by

Jacobite agents constructed around the pretence of luring him to visit a dying parishioner. He attended with an armed servant and the "parishioner" staged an "instant recovery".

In 1685 Sharp was tasked by the Lord Mayor with drawing up for the

Grand Jury of London their address of congratulations on the accession of

James II and on 20 April 1686 he became

chaplain in ordinary

''In ordinary'' is an English phrase with multiple meanings. In relation to the Royal Household and public officials more generally, it indicates that a position is a permanent one (in contrast to positions that are extraordinary). In naval matt ...

to the King. However, provoked by the subversion of his parishioners' faith by Jesuit priests and Jacobite agents, Sharp preached two sermons at St. Giles on 2 and 9 May, which were held to reflect adversely on the King's religious policy. As a result,

Henry Compton Henry Compton may refer to:

* Henry Compton (bishop) (1632–1713), English bishop and nobleman

* Henry Compton, 1st Baron Compton (1544–1589), English peer, MP for Old Sarum

* Henry Combe Compton (1789–1866), British Conservative Party polit ...

,

bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

, was ordered by the

Lord President of the Council

The Lord President of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. The Lor ...

, to summarily suspend Sharp from his position at St Giles. Compton refused, but in an interview at

Doctors' Commons

Doctors' Commons, also called the College of Civilians, was a society of lawyers practising civil law (legal system), civil (as opposed to common) law in London, namely ecclesiastical and admiralty law. Like the Inns of Court of the common lawye ...

on 18 May privately advised Sharp to "forbear the pulpit" for the present. On 1 July, by the advice of

Judge Jeffreys

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys (15 May 1645 – 18 April 1689), also known as "the Hanging Judge", was a Welsh judge. He became notable during the reign of King James II, rising to the position of Lord Chancellor (and serving as L ...

, he left London for

Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

; but when he returned to London in December his petition, revised by Jeffreys, was received, and in January 1687 he was reinstated.

In August 1688 Sharp was again in trouble. After refusing to read the

declaration of indulgence Declaration of Indulgence may refer to:

* Declaration of Indulgence (1672) by Charles II of England in favour of nonconformists and Catholics

* Declaration of Indulgence (1687) by James II of England granting religious freedom

See also

*Indulgence ...

he summoned before the

ecclesiastical commission of James II. He argued that though obedience was due to the king in preference to the archbishop, yet that obedience went no further than what was legal and honest. After the

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

he visited the imprisoned

'Bloody' Jeffreys in the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

and attempted to bring him to penitence and consolation for his crimes.

Soon after the

Revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

Sharp preached before the

Prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by the stadtholders of, and then the heirs apparent of ...

(soon to be

King William III

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702), also known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from 167 ...

) and three days later before the

Convention Parliament. On each occasion he included prayers for King James II on the ground that the lords had not yet concurred in the

abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the Order of succession, succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of ...

. On 7 September 1689 he was named

dean of Canterbury

The Dean of Canterbury is the head of the Chapter (religion), Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral, the Cathedral of Christ Church, Canterbury, England. The current office of dean (religion), Dean originated after the English Reformation, although Dea ...

succeeding

John Tillotson

John Tillotson (October 1630 – 22 November 1694) was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1691 to 1694.

Curate and rector

Tillotson was the son of a Puritan clothier at Haughend, Sowerby, Yorkshire. Little is known of his early youth; he stu ...

. He was installed as Archbishopric of York in 1691.

The Great Plague in St Giles

The

Bubonic Plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of Plague (disease), plague caused by the Bacteria, bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and ...

or

Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

had first appeared in London in 1348 and persisted recurrently for the next 318 years with the outbreaks of 1362, 1369, 1471, 1479 proving particularly severe.

St.Giles's parish enjoys the unfortunate distinction of having originated last and most severe instance of the plague in London, between 1665 and 1666, a period that has become known as the

Great Plague of London

The Great Plague of London, lasting from 1665 to 1666, was the most recent major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in England. It happened within the centuries-long Second plague pandemic, Second Pandemic, a period of intermittent buboni ...

.

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

records that the first persons to catch the disease were members of a family living at the top of

Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the boundary between the Covent Garden and Holborn areas of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of London Borough of Camden, Camden and the southern part in the City o ...

, 350 yards from the St Giles church. Two Frenchmen staying with a local family caught ill of the plague there and quickly died:

...the latter end of November or the beginning of December 1664 when two men, said to be Frenchmen, died of the plague in Long Acre, or rather at the upper end of Drury Lane

By 7 June 1665 the diarist

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

noticed in the parish of St Giles, for the first time, the dreaded scarlet

Plague Cross

The term plague cross can refer to either a mark placed on a building occupied by victims of plague; or a permanent structure erected, to enable plague sufferers to trade while minimising the risk of contagion. A wide variety of plague cross ...

painted on the doors of the dead and dieing:

I did in Drury-lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and "Lord have mercy upon us" writ there - which was a sad sight to me, being the first of that kind that to my remembrance I ever saw.

By September 1665, 8,000 people were dying a week in London and by the end of the plague year it had claimed an estimated 100,000 people—almost a quarter of

London's population, in 18 months.

By the end of the plague there had been a total 3,216 listed plague deaths in a St Giles parish which had fewer than 2,000 listed households. This is almost certainly an underestimate, however, as the non-reporting of deaths to avoid quarantine measures was widespread. By the end of 1666 the mortal remains of over 1000 parishioners had been deposited in the plague pit in St Giles churchyard with many other corpses being sent to pits at

Golden Square

Golden Square, in Soho, the City of Westminster, London, is a mainly hardscaped garden square planted with a few mature trees and raised borders in Central London flanked by classical office buildings. Its four approach ways are north and so ...

and a site which is now at the corner of Marshall Street and

Beak Street in Soho.

18th–19th centuries, rebuilding and urban expansion

The Henry Flitcroft church

The high number of plague victims buried in and around the church were the probable cause of a damp problem evident by 1711.

The excessive number of burials in the parish had led to the churchyard rising as much as eight feet above the nave floor.

The parishioners petitioned the

Commission for Building Fifty New Churches

The Commission for Building Fifty New Churches (in London and the surroundings) was an organisation set up by Act of Parliament in England in 1711, to implement the New Churches in London and Westminster Act 1710, with the purpose of building f ...

for a grant to rebuild. Initially refused as it was not a new foundation and the Act was intended for new parishes in under-churched areas, the parish was eventually allocated £8,000 (around £1.2 million adjusted for 2023 prices) and a new church was built in 1730–1734, designed by architect

Henry Flitcroft

Henry Flitcroft (30 August 1697 – 25 February 1769) was a major English architect in the second generation of Palladianism. He came from a humble background; his father was a labourer in the gardens at Hampton Court. Flitcroft began his career a ...

in the

Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

style.

The first stone was laid by the

Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the Ordinary (Catholic Church), ordinary of the Church of England Anglican Diocese of Norwich, Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of the county of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. Th ...

on

Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in many Western Christian liturgical calendars on 29 Se ...

, 29 September 1731.

The

Flitcroft rebuilding represents a shift from the

Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

to the

Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

form of church building in England and has been described as 'one of the least known but most significant episodes in

Georgian church design, standing at a crucial crossroads of radical architectural change and representing nothing less than the first

Palladian Revival

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Republic of Venice, Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetr ...

church to be erected in London...".

Nicholas Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor ( – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principal architects ...

had been an early choice to design the new church building at St Giles but tastes had begun to turn against his freewheeling

mannerist

Mannerism is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, when the Baroque style largely replaced it ...

style (his recent work on the nearby

St George's Bloomsbury

St George's, Bloomsbury, is a parish church in Bloomsbury, London Borough of Camden, United Kingdom. It was designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor and consecrated in 1730. The church crypt houses the #Museum of Comedy, Museum of Comedy.

History

The C ...

was strongly criticised).

Instead the young and inexperienced

Henry Flitcroft

Henry Flitcroft (30 August 1697 – 25 February 1769) was a major English architect in the second generation of Palladianism. He came from a humble background; his father was a labourer in the gardens at Hampton Court. Flitcroft began his career a ...

was chosen and he would take as his inspiration and guide the

Caroline buildings of

Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was an English architect who was the first significant Architecture of England, architect in England in the early modern era and the first to employ Vitruvius, Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmet ...

rather than the work of

Wren

Wrens are a family, Troglodytidae, of small brown passerine birds. The family includes 96 species and is divided into 19 genera. All species are restricted to the New World except for the Eurasian wren that is widely distributed in the Old Worl ...

,

Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor ( – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principal architects ...

or

James Gibbs

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was a Scottish architect. Born in Aberdeen, he trained as an architect in Rome, and practised mainly in England. He is an important figure whose work spanned the transition between English Ba ...

.

Only in the matter of the

spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spire ...

of the church, for which

Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one ...

had no model, did Flitcroft borrow as his model the steeple of

James Gibbs's St Martin's in the Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. Dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours, there has been a church on the site since at least the medieval pe ...

but even then, in altering the

Order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

and preferring a solid, belted summit, he made it all his own.

The

wooden model he made so that parishioners could see what they were commissioning, can still be seen in the church's north

transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

. The

Vestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government of a parish in England, Wales and some English colony, English colonies. At their height, the vestries were the only form of local government in many places and spen ...

House was built at the same time.

The Rookery

As London grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, so did the parish's population, eventually reaching 30,000 by 1831 which suggests an extremely high density.

It included two neighbourhoods noted for poverty and squalor: the St Giles

Rookery

A rookery is a colony of breeding rooks, and more broadly a colony of several types of breeding animals, generally gregarious birds.

Coming from the nesting habits of rooks, the term is used for corvids and the breeding grounds of colony-fo ...

between the church and

Great Russell Street

Great Russell Street is a street in Bloomsbury, London, best known for being the location of the British Museum. It runs between Tottenham Court Road (part of the A400 route) in the west, and Southampton Row (part of the A4200 route) in the e ...

, and the

Seven Dials north of

Long Acre

Long Acre is a street in the City of Westminster in central London. It runs from St Martin's Lane, at its western end, to Drury Lane in the east. The street was completed in the early 17th century and was once known for its Coach_(carriage), co ...

.

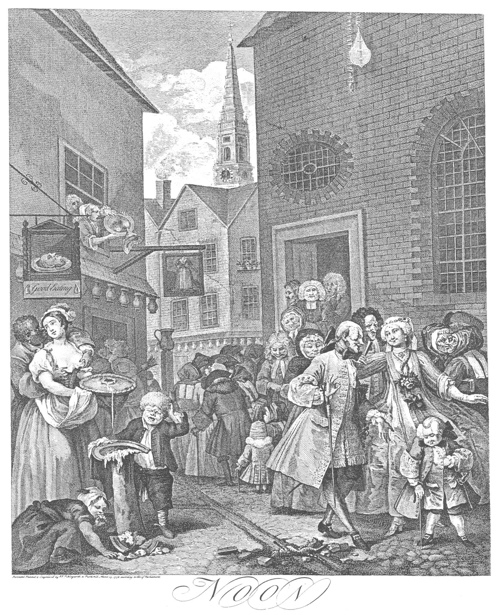

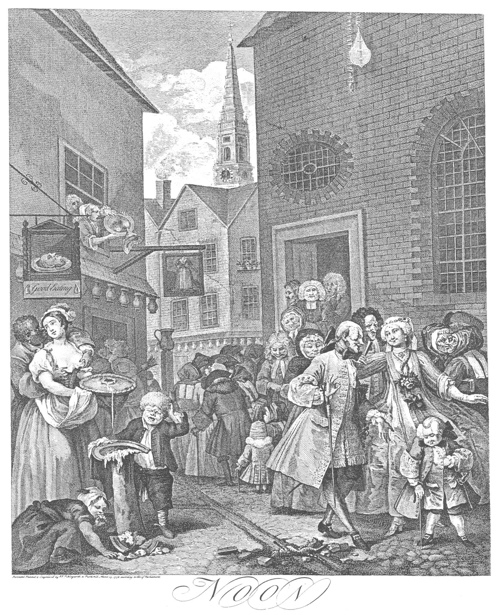

These became a centre for criminality and prostitution and the name St Giles became associated with the underworld, gambling houses and the consumption of gin.

St Giles's Roundhouse was a gaol and

St Giles' Greek a

thieves' cant

Thieves' cant (also known as thieves' argot, rogues' cant, or peddler's French) is a cant (language), cant, cryptolect, or argot which was formerly used by thieves, beggars, and hustlers of various kinds in Great Britain and to a lesser extent i ...

. As the population grew, so did their dead, and eventually there was no room in the graveyard: many burials of parishioners (including the architect

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professor of architecture at the Ro ...

) in the 18th and 19th centuries took place outside the parish in the churchyard of

St Pancras old church

St Pancras Old Church is a Church of England parish church on Pancras Road, Somers Town, London, Somers Town, in the London Borough of Camden. Somers Town is an area of the ancient parish and later Metropolitan Borough of St Pancras, London, St ...

John Wesley

John Wesley ( ; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a principal leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies ...

, the English cleric, theologian, and evangelist and leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as

Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

is believed to have preached occasionally at

Evening Prayer Evening Prayer refers to:

: Evening Prayer (Anglican), an Anglican liturgical service which takes place after midday, generally late afternoon or evening. When significant components of the liturgy are sung, the service is referred to as "Evensong". ...

at St Giles from the large pulpit dating from 1676 which survived the rebuild and, indeed, is still in use today. Also retained in the church is a smaller whitewashed box-pulpit originally belonging to the nearby

West Street Chapel

The West Street Chapel is a former chapel at 24 West Street, London WC2. It was John Wesley’s first Methodist chapel in London's West End.

History

The chapel was built for a Huguenot congregation who has previously worshipped in Newport Mar ...

used by both John and

Charles Wesley

Charles Wesley (18 December 1707 – 29 March 1788) was an English Anglican cleric and a principal leader of the Methodist movement. Wesley was a prolific hymnwriter who wrote over 6,500 hymns during his lifetime. His works include "And Can It ...

to preach the Gospel.

The dissolute nature of the area in the middle part of the 19th century is described in

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

' ''

Sketches by Boz

Sketch or Sketches may refer to:

* Sketch (drawing), a rapidly executed freehand drawing that is not usually intended as a finished work

Arts, entertainment and media

* Sketch comedy, a series of short scenes or vignettes called sketches

Fil ...

''.

Architects

Sir Arthur Blomfield

Sir Arthur William Blomfield (6 March 182930 October 1899) was an English architect. He became president of the Architectural Association in 1861; a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1867 and vice-president of the RIBA in ...

and

William Butterfield

William Butterfield (7 September 1814 – 23 February 1900) was a British Gothic Revival architect and associated with the Oxford Movement (or Tractarian Movement). He is noted for his use of polychromy.

Biography

William Butterfield was bo ...

made minor alterations to the church interior in 1875 and 1896.

20th century, war damage and restoration

Although St Giles escaped direct bombing hits in the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, high explosives still destroyed most of its Victorian stained glass and the roof of the nave was severely damaged.

The Vestry house was filled with rubble and the churchyard was fenced with chicken wire, while the Rectory on Great Russell Street had been entirely destroyed. The Parish itself was in as parlous a state with the theft of the PCC funds and the surrounding area ruined and parishioners dispersed by war. Into this position the Revd Gordon Taylor was appointed Rector and set about energetically rebuilding the church and parish.

The church was designated a Grade I

listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

on 24 October 1951 and Revd. Gordon Taylor raised funds for a major restoration of the church undertaken between 1952 and 1953. It adhered closely to Flitcroft's original intentions, on which the

Georgian Group and

Royal Fine Art Commission

The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) was an executive non-departmental public body of the UK government, established in 1999. It was funded by both the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and the Department for ...

were consulted The resulting works were praised by the journalist and poet

John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman, (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architect ...

as "one of the most successful post-war church restorations" (''Spectator'' 9 March 1956).

Revd. Gordon Taylor slowly rebuilt the congregation, refurbished the St Giles's

Almshouse

An almshouse (also known as a bede-house, poorhouse, or hospital) is charitable housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the Middle Ages. They were often built for the poor of a locality, for those who had held ce ...

s and reinvigorated the ancient parochial charities. He also worked successfully with Austen Williams of

St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. Dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours, there has been a church on the site since at least the medieval pe ...

to defeat the comprehensive redevelopment of

Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

, stopping the construction of a major road planned to run through the parish, which would have involved the demolition of the Almshouses and the destruction of this historic quarter of London, personally giving evidence before the public inquiry.

After initially welcoming the liturgical and pastoral innovations of the 1960s Rev. Taylor eventually came to see himself and St Giles as defenders and custodians of the traditions of the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, the Established Liturgy and the use of the