Spinoza's Ethics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

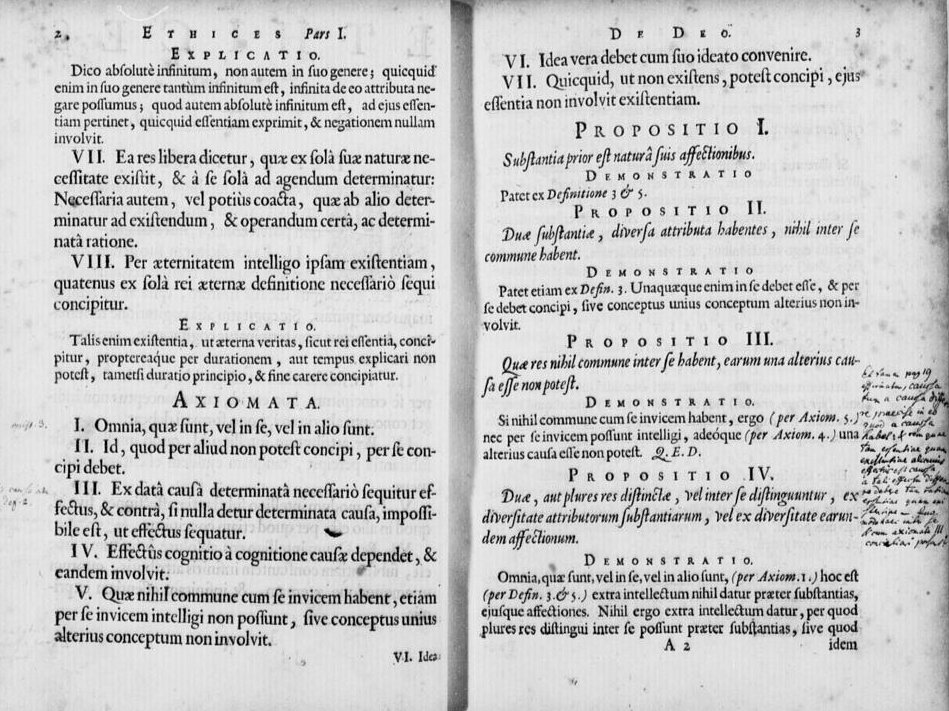

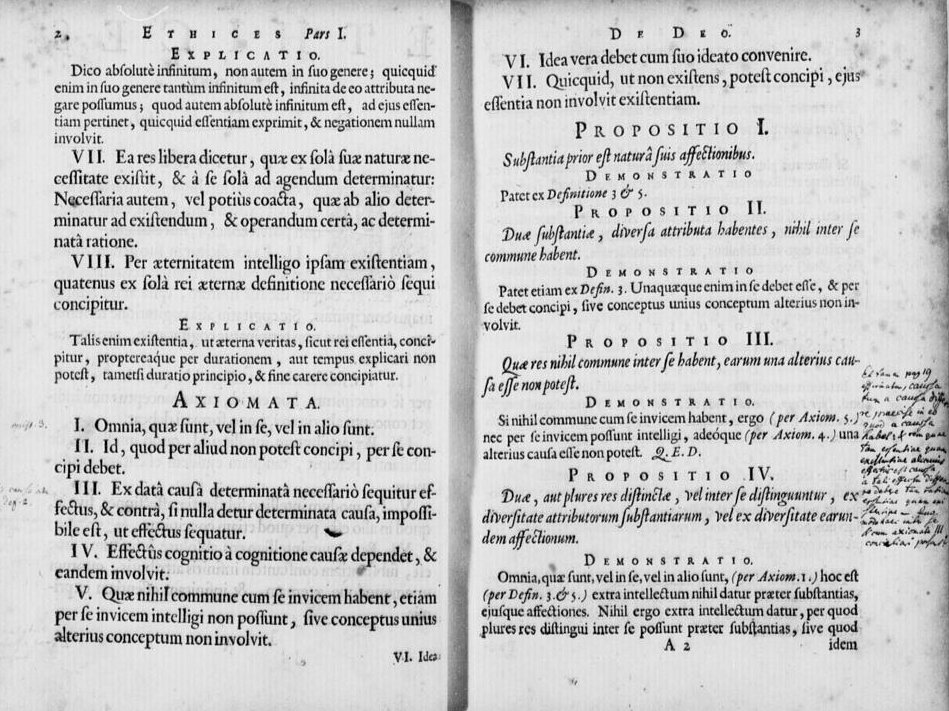

''Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order'' () is a philosophical

"Introduction to Spinoza's ''Ethics''"

, by Geoff Pynn,

According to Spinoza, God has "attributes". One attribute is 'extension', another attribute is 'thought', and there are infinitely many such attributes. Since Spinoza holds that to exist is to ''act'', some readers take 'extension' to refer to an activity characteristic of bodies (for example, the active process of taking up space, exercising physical power, or resisting a change of place or shape). They take 'thought' to refer to the activity that is characteristic of minds, namely thinking, the exercise of mental power. Each attribute has modes. All bodies are modes of extension, and all ideas are modes of thought.

According to Spinoza, God has "attributes". One attribute is 'extension', another attribute is 'thought', and there are infinitely many such attributes. Since Spinoza holds that to exist is to ''act'', some readers take 'extension' to refer to an activity characteristic of bodies (for example, the active process of taking up space, exercising physical power, or resisting a change of place or shape). They take 'thought' to refer to the activity that is characteristic of minds, namely thinking, the exercise of mental power. Each attribute has modes. All bodies are modes of extension, and all ideas are modes of thought.

— which respectively represent an interpretation and commentary of the philosopher's stance on "Modal Metaphysics", "Theory of Attributes", "Psychological Theory", "Physical Theory", and are currently cited as a reference within the present text.

For Spinoza, reality means activity, and the reality of anything expresses itself in a tendency to self-preservation — to exist is to persist. In the lowest kinds of things, in so-called inanimate matter, this tendency shows itself as a "will to live". Regarded physiologically the effort is called ''appetite''; when we are conscious of it, it is called ''desire''. The moral categories, good and evil, are intimately connected with desire, though not in the way commonly supposed. Man does not desire a thing because he thinks it is good, or shun it because he considers it bad; rather he considers anything good if he desires it, and regards it as bad if he has an aversion for it. Now whatever is felt to heighten vital activity gives pleasure; whatever is felt to lower such activity causes pain. Pleasure coupled with a consciousness of its external cause is called love, and pain coupled with a consciousness of its external cause is called hate — "love" and "hate" being used in the wide sense of "like" and "dislike". All human feelings are derived from pleasure, pain and desire. Their great variety is due to the differences in the kinds of external objects which give rise to them, and to the differences in the inner conditions of the individual experiencing them.

Spinoza gives a detailed analysis of the whole gamut of human feelings, and his account is one of the classics of

For Spinoza, reality means activity, and the reality of anything expresses itself in a tendency to self-preservation — to exist is to persist. In the lowest kinds of things, in so-called inanimate matter, this tendency shows itself as a "will to live". Regarded physiologically the effort is called ''appetite''; when we are conscious of it, it is called ''desire''. The moral categories, good and evil, are intimately connected with desire, though not in the way commonly supposed. Man does not desire a thing because he thinks it is good, or shun it because he considers it bad; rather he considers anything good if he desires it, and regards it as bad if he has an aversion for it. Now whatever is felt to heighten vital activity gives pleasure; whatever is felt to lower such activity causes pain. Pleasure coupled with a consciousness of its external cause is called love, and pain coupled with a consciousness of its external cause is called hate — "love" and "hate" being used in the wide sense of "like" and "dislike". All human feelings are derived from pleasure, pain and desire. Their great variety is due to the differences in the kinds of external objects which give rise to them, and to the differences in the inner conditions of the individual experiencing them.

Spinoza gives a detailed analysis of the whole gamut of human feelings, and his account is one of the classics of

''Journal of Philosophical Studies''

Vol. 3, No. 12 (Oct., 1928), pp. 544–545.

Project Gutenberg

Original Latin text on Wikisource

EthicaDB

hosts translations in several languages.

EarlyModernTexts

contains a simplified and abridged translation of the ''Ethics'', by Jonathan Bennett * *

Mapping Spinoza's ''Ethics''

: visual representations of the connections between propositions in the ''Ethics''.

Ethicaweb

Hyperlinked Ethica's propositions, including defined and undefined philosophical terms. {{Authority control 1677 non-fiction books 1677 in the Dutch Republic 17th-century books in Latin Ethics books Works by Baruch Spinoza Books published posthumously Books about emotions Treatises God in culture Censored books

treatise

A treatise is a Formality, formal and systematic written discourse on some subject concerned with investigating or exposing the main principles of the subject and its conclusions."mwod:treatise, Treatise." Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Acc ...

written in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

by Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

(). It was written between 1661 and 1675 and was first published posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award, an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication, publishing of creative work after the author's death

* Posthumous (album), ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1 ...

in 1677.

The ''Ethics'' is perhaps the most ambitious attempt to apply Euclid

Euclid (; ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of geometry that largely domina ...

's method

Method (, methodos, from μετά/meta "in pursuit or quest of" + ὁδός/hodos "a method, system; a way or manner" of doing, saying, etc.), literally means a pursuit of knowledge, investigation, mode of prosecuting such inquiry, or system. In re ...

in philosophy. Spinoza puts forward a small number of definitions and axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

s from which he attempts to derive hundreds of propositions

A proposition is a statement that can be either true or false. It is a central concept in the philosophy of language, semantics, logic, and related fields. Propositions are the object s denoted by declarative sentences; for example, "The sky ...

and corollaries

In mathematics and logic, a corollary ( , ) is a theorem of less importance which can be readily deduced from a previous, more notable statement. A corollary could, for instance, be a proposition which is incidentally proved while proving another ...

, such as "when the Mind imagines its own lack of power, it is saddened by it", "a free man thinks of nothing less than of death", and "the human Mind cannot be absolutely destroyed with the Body, but something of it remains which is eternal."

Summary

Part I: Of God

The first part of the book addresses the relationship between God and theuniverse

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

. Spinoza was engaging with a tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

that held that God exists outside of the universe, that God created the universe for a reason, and that God could have created a different universe according to his will. Spinoza denies each point. According to Spinoza, God ''is'' the natural world. Spinoza concludes that God is the substance comprising the universe; that God exists in itself, not outside of the universe; and that the universe exists as it does from necessity, not because of a divine theological reason or will.

Spinoza argues through propositions. He considers the conclusions he reaches to be the necessary logical result of combining the Definitions and Axioms he provides. He starts with the proposition that "there cannot exist in the universe two or more substances having the same nature or attribute." He then argues that objects and events must not merely be caused if they occur, but that they must be prevented if they do not. If something is non-contradictory, there is no reason that it should not exist. Spinoza builds from these starting ideas. If substance exists it must be infinite, because if it is not infinite another finite substance would have to exist to take up the remaining parts of its finite attributes, something that is impossible according to an earlier proposition. Spinoza then uses the Ontological Argument

In the philosophy of religion, an ontological argument is a deductive philosophical argument, made from an ontological basis, that is advanced in support of the existence of God. Such arguments tend to refer to the state of being or existing. ...

as the justification for the existence of God and argues that God must possess all attributes infinitely. Since no two things can share attributes, "besides God no substance can be granted or conceived."

As with many of Spinoza's claims, what this means is a matter of dispute. Spinoza claims that the things that make up the universe, including human beings, are God's "modes". This means that everything is, in some sense, dependent upon God. The nature of this dependence is disputed. Some scholars say that the modes are properties

Property is the ownership of land, resources, improvements or other tangible objects, or intellectual property.

Property may also refer to:

Philosophy and science

* Property (philosophy), in philosophy and logic, an abstraction characterizing an ...

of God in the traditional sense. Others say that modes are effect

Effect may refer to:

* A result or change of something

** List of effects

** Cause and effect, an idiom describing causality

Pharmacy and pharmacology

* Drug effect, a change resulting from the administration of a drug

** Therapeutic effect, ...

s of God. Either way, the modes are also logically dependent on God's essence, in this sense: everything that happens follows from the nature of God, just as it follows from the nature of a triangle that the sum of its angles are equal to two right angles or 180 degrees. Since God had to exist with the nature that he has, nothing that has happened could have been avoided; and, if God has fixed a particular fate for a particular mode, there is no escaping it. As Spinoza puts it, "A thing which has been determined by God to produce an effect cannot render itself undetermined."

Part II: Of the Nature & Origin of the Mind

The second part focuses on the human mind and body. Spinoza attacks several Cartesian positions: (1) that the mind and body are distinct substances that can affect one another; (2) that we know our minds better than we know our bodies; (3) that our senses may be trusted; (4) that despite being created by God we can make mistakes, namely, when we affirm, of our own free will, an idea that is not clear and distinct. Spinoza denies each of Descartes's points. Regarding (1), Spinoza argues that the mind and the body are a single thing that is being thought of in two different ways. The whole of nature can be fully described in terms of thoughts or in terms of bodies. However, we cannot mix these two ways of describing things, as Descartes does, and say that the mind affects the body or vice versa. Moreover, the mind's self-knowledge is not fundamental: it cannot know its own thoughts better than it knows the ways in which its body is acted upon by other bodies. Further, there is no difference between contemplating an idea and thinking that it is true, and there is no freedom of the will at all. Sensory perception, which Spinoza calls "knowledge of the first kind", is entirely inaccurate, since it reflects how our own bodies work more than how things really are. We can also have a kind of accurate knowledge called "knowledge of the second kind", or "reason". This encompasses knowledge of the features common to all things, and includes principles of physics and geometry. We can also have "knowledge of the third kind", or " intuitive knowledge". This is a sort of knowledge that, somehow, relates particular things to the nature of God.Part III: Of the Origin & Nature of Emotions

In the third part of the ''Ethics'', Spinoza argues that all things, including human beings, strive to preserve their perfection of power in being unaffected. Spinoza states thatvirtue

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be morality, moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is Value (ethics), valued as an Telos, end purpos ...

is equal to power

Power may refer to:

Common meanings

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power, a type of energy

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

Math ...

(i.e., self-control

Self-control is an aspect of inhibitory control, one of the core executive functions. Executive functions are cognitive processes that are necessary for regulating one's behavior in order to achieve specific goals.

Defined more independen ...

).

Spinoza explains how this desire

Desires are states of mind that are expressed by terms like "wanting", "wishing", "longing" or "craving". A great variety of features is commonly associated with desires. They are seen as propositional attitudes towards conceivable states of affa ...

("conatus

In the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza, conatus (; :wikt:conatus; Latin for "effort; endeavor; impulse, inclination, tendency; undertaking; striving") is an innate inclination of a thing to continue to exist and enhance itself. This ''thing'' may ...

") underlies the movement and complexity of our emotion

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiology, neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavior, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or suffering, displeasure. There is ...

s and passions (i.e., joy and sadness that are building blocks for all other emotions). Our mind is in certain cases active, and in certain cases passive. In so far as it has adequate ideas it is necessarily active, and in so far as it has inadequate ideas, it is necessarily passive.

Definitions of the Affects

Part IV: Of the Servitude of Humanity, or the Strength of the Emotions

The fourth part analyzes human passions, which Spinoza sees as aspects of the mind that direct us outwards to seek what gives pleasure and shun what gives pain. The "bondage" he refers to is domination by these passions or " affects" as he calls them. Spinoza considers how the affects, ungoverned, can torment people and make it impossible for mankind to live in harmony with one another.Part V: Of the Power of the Intellect, or the Liberty of Humanity

The fifth part argues that reason can govern the affects in the pursuit of virtue, which for Spinoza isself-preservation

Self-preservation is a behavior or set of behaviors that ensures the survival of an organism. It is thought to be universal among all living organisms.

Self-preservation is essentially the process of an organism preventing itself from being harm ...

: only with the aid of reason can humans distinguish the passions that truly aid virtue from those that are ultimately harmful. By reason, we can see things as they truly are, '' sub specie aeternitatis'', "under the aspect of eternity," and because Spinoza treats God and nature as indistinguishable, by knowing things as they are we improve our knowledge of God. Seeing that all things are determined by nature to be as they are, we can achieve the rational tranquility that best promotes our happiness, and liberate ourselves from being driven by our passions.

Themes

God or Nature

According to Spinoza, God is Nature and Nature is God (''Deus sive Natura''). This is hispantheism

Pantheism can refer to a number of philosophical and religious beliefs, such as the belief that the universe is God, or panentheism, the belief in a non-corporeal divine intelligence or God out of which the universe arisesAnn Thomson; Bodies ...

. In his previous book, '' Theologico-Political Treatise'', Spinoza discussed the inconsistencies that result when God is assumed to have human characteristics. In the third chapter of that book, he stated that the word "God" means the same as the word "Nature". He wrote: "Whether we say ... that all things happen according to the laws of nature, or are ordered by the decree and direction of God, we say the same thing." He later qualified this statement in his letter to Oldenburg by abjuring materialism

Materialism is a form of monism, philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental Substance theory, substance in nature, and all things, including mind, mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. Acco ...

. Nature, to Spinoza, is a metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

substance

Substance may refer to:

* Matter, anything that has mass and takes up space

Chemistry

* Chemical substance, a material with a definite chemical composition

* Drug, a chemical agent affecting an organism

Arts, entertainment, and media Music

* ' ...

, not physical matter. In this posthumously published book ''Ethics'', he equated God with nature by writing "God or Nature" four times. " r Spinoza, God or Nature—being one and the same thing—is the whole, infinite, eternal, necessarily existing, active system of the universe within which absolutely everything exists. This is the fundamental principle of the ''Ethics''...."

Spinoza holds that everything that exists is part of nature, and everything in nature follows the same basic laws. In this perspective, human beings are part of nature, and hence they can be explained and understood in the same way as everything else in nature. This aspect of Spinoza's philosophy — his naturalism — was radical for its time, and perhaps even for today. In the preface to Part III of ''Ethics'' (relating to emotions), he writes:

Therefore, Spinoza affirms that the passions of hatred, anger, envy, and so on, considered in themselves, "follow from this same necessity and efficacy of nature; they answer to certain definite causes, through which they are understood, and possess certain properties as worthy of being known as the properties of anything else". Humans are not different in kind from the rest of the natural world; they are part of it.Cf"Introduction to Spinoza's ''Ethics''"

, by Geoff Pynn,

Northern Illinois University

Northern Illinois University (NIU) is a public research university in DeKalb, Illinois, United States. It was founded as "Northern Illinois State Normal School" in 1895 by Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld, initially to provide the state with c ...

, Spring 2012.

Spinoza's naturalism can be seen as deriving from his firm commitment to the principle of sufficient reason

The principle of sufficient reason states that everything must have a Reason (argument), reason or a cause. The principle was articulated and made prominent by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, with many antecedents, and was further used and developed by ...

(), which is the thesis that everything has an explanation. He articulates the in a strong fashion, as he applies it not only to everything that is, but also to everything that is not:

And to continue with Spinoza's triangle example, here is one claim he makes about God:

Spinoza rejected the idea of an external Creator suddenly, and apparently capriciously, creating the world at one particular time rather than another, and creating it out of nothing. The solution appeared to him more perplexing than the problem, and rather unscientific in spirit as involving a break in continuity. He preferred to think of the entire system of reality as its own ground. This view was simpler; it avoided the impossible conception of creation out of nothing; and it was religiously more satisfying by bringing God and man into closer relationship. Instead of Nature, on the one hand, and a supernatural God, on the other, he posited one world of reality, at once Nature and God, and leaving no room for the supernatural. This so-called naturalism of Spinoza is only distorted if one starts with a crude materialistic idea of Nature and supposes that Spinoza degraded God. The truth is that he raised Nature to the rank of God by conceiving Nature as the fulness of reality, as the One and All. He rejected the specious simplicity obtainable by denying the reality of Matter, or of Mind, or of God. The cosmic system comprehends them all. In fact, God and Nature become identical when each is conceived as the Perfect Self-Existent. This constitutes Spinoza's ''Pantheism''.

Structure of reality

According to Spinoza, God has "attributes". One attribute is 'extension', another attribute is 'thought', and there are infinitely many such attributes. Since Spinoza holds that to exist is to ''act'', some readers take 'extension' to refer to an activity characteristic of bodies (for example, the active process of taking up space, exercising physical power, or resisting a change of place or shape). They take 'thought' to refer to the activity that is characteristic of minds, namely thinking, the exercise of mental power. Each attribute has modes. All bodies are modes of extension, and all ideas are modes of thought.

According to Spinoza, God has "attributes". One attribute is 'extension', another attribute is 'thought', and there are infinitely many such attributes. Since Spinoza holds that to exist is to ''act'', some readers take 'extension' to refer to an activity characteristic of bodies (for example, the active process of taking up space, exercising physical power, or resisting a change of place or shape). They take 'thought' to refer to the activity that is characteristic of minds, namely thinking, the exercise of mental power. Each attribute has modes. All bodies are modes of extension, and all ideas are modes of thought.

Substance, attributes, modes

Spinoza's ideas relating to the character and structure of reality are expressed by him in terms of ''substance'', ''attributes'', and ''modes''. These terms are very old and familiar, but not in the sense in which Spinoza employs them. To understand Spinoza, it is necessary to lay aside all preconceptions about them, and follow Spinoza closely. Spinoza found it impossible to understand the finite, dependent, transient objects and events of experience without assuming some reality not dependent on anything else but self-existent, not produced by anything else but eternal, not restricted or limited by anything else but infinite. Such an uncaused, self-sustaining reality he called ''substance''. So, for instance, he could not understand the reality of material objects and physical events without assuming the reality of a self-existing, infinite and eternal physical force which expresses itself in all the movements and changes which occur, as we say, inspace

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

.

This physical force he called ''extension'', and described it, at first, as a ''substance'', in the sense just explained. Similarly, he could not understand the various dependent, transient mental experiences with which we are familiar without assuming the reality of a self-existing, infinite and eternal consciousness, mental force, or mind-energy, which expresses itself in all these finite experiences of perceiving and understanding, of feeling and striving. This consciousness or mind-energy he called ''thought'', and described it also, at first, as a ''substance''.Especially valuable for these specific sections of Spinoza's thought as expounded in his ''Ethics'', have been the online pages by the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (''SEP'') is a freely available online philosophy resource published and maintained by Stanford University, encompassing both an online encyclopedia of philosophy and peer-reviewed original publication ...

'' at these four link— which respectively represent an interpretation and commentary of the philosopher's stance on "Modal Metaphysics", "Theory of Attributes", "Psychological Theory", "Physical Theory", and are currently cited as a reference within the present text.

Galilean

Generically, a Galilean (; ; ; ) is a term that was used in classical sources to describe the inhabitants of Galilee, an area of northern Israel and southern Lebanon that extends from the northern coastal plain in the west to the Sea of Galile ...

physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

tended to regard the whole world of physical phenomena

Physical may refer to:

*Physical examination

In a physical examination, medical examination, clinical examination, or medical checkup, a medical practitioner examines a patient for any possible medical signs or symptoms of a Disease, medical co ...

as the result of differences of motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

or momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (: momenta or momentums; more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. ...

. And, though erroneously conceived, the Cartesian conception of a constant quantity of motion in the world led Spinoza to conceive of all physical phenomena as so many varying expressions of that store of motion (or motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

and rest

REST (Representational State Transfer) is a software architectural style that was created to describe the design and guide the development of the architecture for the World Wide Web. REST defines a set of constraints for how the architecture of ...

).

Spinoza might, of course, have identified Extension with energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

of motion. But, with his usual caution, he appears to have suspected that motion may be only one of several types of physical energy. So he described motion simply as a mode of Extension, but as an ''infinite'' mode (because complete or exhaustive of all finite modes of motion) and as an ''immediate'' mode (as a direct expression of Extension). Again, the physical world (or "the face of the world as a whole", as Spinoza calls it) retains a certain sameness in spite of the innumerable changes in detail that are going on. Accordingly, Spinoza described also the physical world as a whole as an ''infinite'' mode of extension ("infinite" because exhaustive of all facts and events that can be reduced to motion), but as a ''mediate'' (or indirect) mode, because he regarded it as the outcome of the conservation of motion (itself a mode, though an ''immediate'' mode). The physical things and events of ordinary experience are ''finite'' modes. In essence each of them is part of the Attribute Extension, which is active in each of them. But the finiteness of each of them is due to the fact that it is restrained or hedged in, so to say, by other finite modes. This limitation or determination is negation in the sense that each finite mode is ''not'' the whole attribute Extension; it is not the other finite modes. But each mode is positively real and ultimate as part of the Attribute.

In the same kind of way the Attribute Thought exercises its activity in various mental processes, and in such systems of mental process as are called minds or souls. But in this case, as in the case of Extension, Spinoza conceives of the finite modes of Thought as mediated by infinite modes. The immediate infinite mode of Thought he describes as "the idea of God"; the mediate infinite mode he calls "the infinite idea" or "the idea of all things". The other Attributes (if any) must be conceived in an analogous manner. And the whole Universe or Substance is conceived as one dynamic system of which the various Attributes are the several world-lines along which it expresses itself in all the infinite variety of events.

Given the persistent misinterpretation of Spinozism it is worth emphasizing the dynamic character of reality as Spinoza conceived it. The cosmic system is certainly a logical or rational system, according to Spinoza, for Thought is a constitutive part of it; but it is not ''merely'' a logical system — it is dynamic as well as logical. His frequent use of geometrical illustrations affords no evidence at all in support of a purely logico-mathematical

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

interpretation of his philosophy; for Spinoza regarded geometrical figures, not in a Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

nic or static manner, but as things traced out by moving particles

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

or lines, etc., that is, dynamically.

Moral philosophy

For Spinoza, reality means activity, and the reality of anything expresses itself in a tendency to self-preservation — to exist is to persist. In the lowest kinds of things, in so-called inanimate matter, this tendency shows itself as a "will to live". Regarded physiologically the effort is called ''appetite''; when we are conscious of it, it is called ''desire''. The moral categories, good and evil, are intimately connected with desire, though not in the way commonly supposed. Man does not desire a thing because he thinks it is good, or shun it because he considers it bad; rather he considers anything good if he desires it, and regards it as bad if he has an aversion for it. Now whatever is felt to heighten vital activity gives pleasure; whatever is felt to lower such activity causes pain. Pleasure coupled with a consciousness of its external cause is called love, and pain coupled with a consciousness of its external cause is called hate — "love" and "hate" being used in the wide sense of "like" and "dislike". All human feelings are derived from pleasure, pain and desire. Their great variety is due to the differences in the kinds of external objects which give rise to them, and to the differences in the inner conditions of the individual experiencing them.

Spinoza gives a detailed analysis of the whole gamut of human feelings, and his account is one of the classics of

For Spinoza, reality means activity, and the reality of anything expresses itself in a tendency to self-preservation — to exist is to persist. In the lowest kinds of things, in so-called inanimate matter, this tendency shows itself as a "will to live". Regarded physiologically the effort is called ''appetite''; when we are conscious of it, it is called ''desire''. The moral categories, good and evil, are intimately connected with desire, though not in the way commonly supposed. Man does not desire a thing because he thinks it is good, or shun it because he considers it bad; rather he considers anything good if he desires it, and regards it as bad if he has an aversion for it. Now whatever is felt to heighten vital activity gives pleasure; whatever is felt to lower such activity causes pain. Pleasure coupled with a consciousness of its external cause is called love, and pain coupled with a consciousness of its external cause is called hate — "love" and "hate" being used in the wide sense of "like" and "dislike". All human feelings are derived from pleasure, pain and desire. Their great variety is due to the differences in the kinds of external objects which give rise to them, and to the differences in the inner conditions of the individual experiencing them.

Spinoza gives a detailed analysis of the whole gamut of human feelings, and his account is one of the classics of psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

. For the present purpose the most important distinction is that between "active" feelings and "passive" feelings (or "passions"). Man, according to Spinoza, is active or free in so far as any experience is the outcome solely of his own nature; he is passive, or a bondsman, in so far as any experience is due to other causes besides his own nature. The active feelings are all of them forms of self-realisation, of heightened activity, of strength of mind, and are therefore always pleasurable. It is the passive feelings (or "passions") which are responsible for all the ills of life, for they are induced largely by things outside us and frequently cause that lowered vitality which means pain. Spinoza next links up his ethics with his theory of knowledge, and correlates the moral progress of man with his intellectual progress. At the lowest stage of knowledge, that of "opinion", man is under the dominant influence of things outside himself, and so is in the bondage of the passions. At the next stage, the stage of "reason", the characteristic feature of the human mind, its intelligence, asserts itself, and helps to emancipate him from his bondage to the senses and external allurements. The insight gained into the nature of the passions helps to free man from their domination. A better understanding of his own place in the cosmic system and of the place of all the objects of his likes and dislikes, and his insight into the necessity which rules all things, tend to cure him of his resentments, regrets and disappointments. He grows reconciled to things, and wins peace of mind. In this way reason teaches acquiescence in the universal order, and elevates the mind above the turmoil of passion. At the highest stage of knowledge, that of "intuitive knowledge", the mind apprehends all things as expressions of the eternal cosmos

The cosmos (, ; ) is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos is studied in cosmologya broad discipline covering ...

. It sees all things in God, and God in all things. It feels itself as part of the eternal order, identifying its thoughts with cosmic thought and its interests with cosmic interests. Thereby it becomes eternal as one of the eternal ideas in which the Attribute Thought expresses itself, and attains to that "blessedness" which "is not the reward of virtue, but virtue itself", that is, the perfect joy which characterises perfect self-activity. This is not an easy or a common achievement. "But", says Spinoza, "everything excellent is as difficult as it is rare."Cf. also ''The correspondence of Spinoza'', G. Allen & Unwin ltd., 1928, p. 289. See also John Laird''Journal of Philosophical Studies''

Vol. 3, No. 12 (Oct., 1928), pp. 544–545.

Reception

Shortly after his death in 1677, Spinoza's works were placed on the Catholic Church's ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The (English: ''Index of Forbidden Books'') was a changing list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former dicastery of the Roman Curia); Catholics were forbidden to print or re ...

''. Condemnations soon appeared, such as Aubert de Versé's ''L'impie convaincu'' (1685). According to its subtitle, in this work "the foundations of pinoza'satheism are refuted". In June 1678—just over a year after Spinoza's death—the States of Holland The States of Holland and West Frisia () were the representation of the two Estates (''standen'') to the court of the Count of Holland. After the United Provinces were formed — and there no longer was a count, but only his "lieutenant" (the stad ...

banned his entire works, since they "contain very many profane, blasphemous and atheistic propositions". The prohibition included the owning, reading, distribution, copying, and restating of Spinoza's books, and even the reworking of his fundamental ideas.

For the next hundred years, if European philosophers read this so-called heretic, they did so almost entirely in secret. How much forbidden Spinozism they were sneaking into their diets remains a subject of continual intrigue. Locke, Hume, Leibniz and Kant all stand accused by later scholars of indulging in periods of closeted Spinozism. At the close of the 18th century, a controversy centering on the ''Ethics'' scandalized the German philosophy scene.

The first known translation of the ''Ethics'' into English was completed in 1856 by the novelist George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

, though not published until much later. The book next appeared in English in 1883, by the hand of the novelist Hale White. Spinoza rose clearly into view for Anglophone metaphysicians in the late nineteenth century, during the British craze for Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

. In his admiration for Spinoza, Hegel was joined in this period by his countrymen Schelling, Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

, Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work '' The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the manife ...

and Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche became the youngest pro ...

. In the twentieth century, the ghost of Spinoza continued to show itself, for example in the writings of Russell, Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language.

From 1929 to 1947, Witt ...

, Davidson, and Deleuze

Gilles Louis René Deleuze (18 January 1925 – 4 November 1995) was a French philosopher who, from the early 1950s until his death in 1995, wrote on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art. His most popular works were the two volumes o ...

. Among writers of fiction and poetry, the influential thinkers inspired by Spinoza include Clarice Lispector, Coleridge, George Eliot, Melville, Borges, and Malamud.

The first published Dutch translations were by the poet Herman Gorter

Herman Gorter (; 26 November 1864 – 15 September 1927) was a Dutch poet and council communist theoretician. He was a leading member of the Tachtigers, a highly influential group of Dutch writers who worked together in Amsterdam in the 1880 ...

(1895) and by Willem Meyer (1896).

Criticism

Number of attributes

Spinoza's contemporary, Simon de Vries, raised the objection that Spinoza fails to prove that substances may possess multiple attributes, but that if substances have only a single attribute, "where there are two different attributes, there are also different substances". This is a serious weakness in Spinoza's logic, which has yet to be conclusively resolved. Some have attempted to resolve this conflict, such as Linda Trompetter, who writes that "attributes are singly essential properties, which together constitute the one essence of a substance", but this interpretation is not universal, and Spinoza did not clarify the issue in his response to de Vries. On the other hand, Stanley Martens states that "an attribute of a substance ''is'' that substance; it is that substance insofar as it has a certain nature" in an analysis of Spinoza's ideas of attributes.Misuse of words

Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work '' The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the manife ...

claimed that Spinoza misused words. "Thus he calls 'God' that which is everywhere called 'the world'; 'justice' that which is everywhere called 'power'; and 'will' that which is everywhere called 'judgement'." Also, "that concept of ''substance''...with the definition of which Spinoza accordingly begins...appears on close and honest investigation to be a higher yet unjustified abstraction of the concept ''matter''."''Parerga and Paralipomena'', vol. I, "Fragments for the History of Philosophy", § 12, p. 76

English translations

* 1856 byGeorge Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

, unpublished until 1981 (Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, University of Salzburg

The University of Salzburg (, ), also known as the Paris Lodron University of Salzburg (''Paris-Lodron-Universität Salzburg'', PLUS), is an Austrian public university in Salzburg, Salzburg municipality, Salzburg (federal state), Salzburg State, ...

, Austria); edited by Thomas Deegan. New edition with an introduction and notes by Clare Carlisle (Princeton University Press, 2020).

* 1870 by Robert Willis, in ''Benedict de Spinoza: His Life, Correspondence, and Ethics'' (Trübner & Co., London).

* 1884 by R. H. L. Elwes, in the second volume of ''The Chief Works'' of Spinoza (George Bell & Sons, London). Many reprints and editions until today.

* 1910 by Andrew Boyle, with an Introduction by George Santayana

George Santayana (born Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás, December 16, 1863 – September 26, 1952) was a Spanish-American philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. Born in Spain, Santayana was raised and educated in the Un ...

(Dens & Sons, London); some reprints since then. Revised by G. H. R. Parkinson and newly edited as a part of the Oxford Philosophical Texts (London, 1989).

* 1982 by Samuel Shirley (Hacket Publications), with Spinoza's selected Letters. Added to his translation of the ''Complete Works'', with introduction and notes by Michael L. Morgan (also Hacket Publications, 2002).

* 1985 by Edwin Curley, in the first volume of ''The Collected Works of Spinoza'' (Princeton University Press). Separately reissued by Penguin Classics (2005), and with a selection of the Letters and other texts in ''A Spinoza Reader'' (Princeton University Press, 1994).

* 2018 by Michael Silverthorne and Matthew J. Kisner in the Cambridge Texts in History of Philosophy series.

See also

* '' Natura naturans'' * '' Natura naturata'' * Nature connectedness * '' Opera Posthuma'' *Pantheism

Pantheism can refer to a number of philosophical and religious beliefs, such as the belief that the universe is God, or panentheism, the belief in a non-corporeal divine intelligence or God out of which the universe arisesAnn Thomson; Bodies ...

* Philosophy of Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

References

Further reading

* * Carlisle, Clare. ''Spinoza's Religion: A New Reading of the 'Ethics. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2021. *Carlisle, Clare, ed. ''Spinoza's 'Ethics, translated byGeorge Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2020.

*Curley, Edwin, ed. ''The Collected Works of Spinoza''. vol. 1. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1985.

*________. ed. ''The Collected Works of Spinoza''. vol. 2. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2016.

* Curley, Edwin M. ''Behind the Geometrical Method. A Reading of Spinoza's Ethics'', Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

*Della Rocca, Michael, ed., 2018. ''The Oxford Handbook of Spinoza''. Oxford University Press.

* Israel, Jonathan, 2023. ''Spinoza: Life and Legacy''. New York: Oxford University Press.

*Kisner, Matthew J., ed. ''Spinoza: Ethics Demonstrated in Geometrical Order''. trans. Michael Silverthorne and Matthew J. Kisner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2018.

* Krop, H. A., 2002, ''Spinoza Ethica'', Amsterdam: Bert Bakker. Later editions, 2017, Amsterdam: Prometheus. In Dutch with Latin text by Spinoza.

* Lloyd, Genevieve, 1996. ''Spinoza and the Ethics''. Routledge.

*Lord, Beth. ''Spinoza's 'Ethics': An Edinburgh Philosophical Guide''. Edinburgh University Press 2010.

* Nadler, Steven. ''Spinoza: A Life''. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press 2018.

*______, ''Spinoza's Ethics: An Introduction'', 2006 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ).

External links

* The 1883 translation of the ''Ethics'' into English by R. H. M. Elwes is available in two places: **Wikisource

Wikisource is an online wiki-based digital library of free-content source text, textual sources operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole; it is also the name for each instance of that project, one f ...

*Project Gutenberg

Original Latin text on Wikisource

EthicaDB

hosts translations in several languages.

EarlyModernTexts

contains a simplified and abridged translation of the ''Ethics'', by Jonathan Bennett * *

Mapping Spinoza's ''Ethics''

: visual representations of the connections between propositions in the ''Ethics''.

Ethicaweb

Hyperlinked Ethica's propositions, including defined and undefined philosophical terms. {{Authority control 1677 non-fiction books 1677 in the Dutch Republic 17th-century books in Latin Ethics books Works by Baruch Spinoza Books published posthumously Books about emotions Treatises God in culture Censored books