Spike Island, County Cork on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spike Island () is an

It was possibly used by smugglers for a time, and a map of circa 1600 clearly shows some form of fortified tower on the island similar to a depiction of

It was possibly used by smugglers for a time, and a map of circa 1600 clearly shows some form of fortified tower on the island similar to a depiction of

In 1802, General

In 1802, General  Two alternative proposals had been made for accommodation within the fort. One envisaged six barrack blocks, one of which was actually constructed in the fort, this being the officers mess block, The ground floor of these blocks consisted of a series of bombproof brick vaulted rooms. The first floor was slate-roofed and open to destruction in the event of a bombardment. The second proposal was for six sets of bombproof casemates set into the ramparts. Two such sets of casemates were actually constructed, these being the north-east and north-west casemates. The second accommodation block to be constructed, the A Block, shows a divergence from the original plan in that the bombproofing is incorporated into the roof. The ground floor of a third block, the B Block, was intended to follow the design of the A block, was erected before the first phase of construction ended (circa 1817). The four

Two alternative proposals had been made for accommodation within the fort. One envisaged six barrack blocks, one of which was actually constructed in the fort, this being the officers mess block, The ground floor of these blocks consisted of a series of bombproof brick vaulted rooms. The first floor was slate-roofed and open to destruction in the event of a bombardment. The second proposal was for six sets of bombproof casemates set into the ramparts. Two such sets of casemates were actually constructed, these being the north-east and north-west casemates. The second accommodation block to be constructed, the A Block, shows a divergence from the original plan in that the bombproofing is incorporated into the roof. The ground floor of a third block, the B Block, was intended to follow the design of the A block, was erected before the first phase of construction ended (circa 1817). The four

Following its handover to Ireland, the island's installations were renamed Fort Mitchel - after

Following its handover to Ireland, the island's installations were renamed Fort Mitchel - after

In May 2006, the then Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell, announced plans to build a new prison on the island. However, in January 2007, it was decided to explore an alternative site for the new prison, and a local task group was set up to re-open Spike Island as a historical tourist site. In 2009, it was announced that ownership of the island would be transferred, free of charge, to

In May 2006, the then Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell, announced plans to build a new prison on the island. However, in January 2007, it was decided to explore an alternative site for the new prison, and a local task group was set up to re-open Spike Island as a historical tourist site. In 2009, it was announced that ownership of the island would be transferred, free of charge, to

Irish National Inventory of Architectural Heritage - Architectural detail on structures on the island

{{County Cork Islands of County Cork Cobh Former populated places in Ireland Prison islands Defunct prisons in the Republic of Ireland Tourist attractions in County Cork

island

An island or isle is a piece of land, distinct from a continent, completely surrounded by water. There are continental islands, which were formed by being split from a continent by plate tectonics, and oceanic islands, which have never been ...

of in Cork Harbour

Cork Harbour () is a natural harbour and river estuary at the mouth of the River Lee (Ireland), River Lee in County Cork, Ireland. It is one of several which lay claim to the title of "second largest natural harbour in the world by navigational ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. Originally the site of a monastic settlement, the island is dominated by an 18th-century bastion fort

A bastion fort or ''trace italienne'' (a phrase derived from non-standard French, meaning 'Italian outline') is a fortification in a style developed during the early modern period in response to the ascendancy of gunpowder weapons such as c ...

now named Fort Mitchel.

The island's strategic location within the harbour meant it was used at times for defence and as a prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where Prisoner, people are Imprisonment, imprisoned under the authority of the State (polity), state ...

. Since the early 21st century the island has been developed as a heritage tourist attraction, with €5.5 million investment in exhibition and visitor spaces and accompanying tourism marketing. There were in excess of 81,000 visitors to the island during 2019, a 21% increase on 2018 numbers. Spike Island was named top European tourist attraction at the 2017 World Travel Awards.

History

Early history

The principal evidence for a monastic foundation on Spike Island comes from Archdall's ''Monasticon Hibernicum'', which states that Saint Mochuda founded a monastery there in the 7th century. A grant to Saint Thomas's Abbey in Dublin in 1178 of the Church of Saint Rusien on Spike Island may lend credence to a monastic settlement, as the name and date both indicate a Celtic foundation. The ruins of a church were reported to exist on Spike Island in 1774.Ownership

The grant to St Thomas's abbey in 1178 coincides with the surrender of lands, including Spike Island, by Diarmid McCarthyKing of Desmond

The following is a list of monarchs of the Kingdom of Desmond. Most were of the MacCarthy Mór ("great MacCarthy"), the senior branch of the MacCarthy dynasty.

12th century MacCarthy

MacCarthy claimants

O'Brien claimants

MacCarthy

13th ...

to the Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

. In 1182, one Raymond Mangunel was granted or "enfeoff

In the Middle Ages, especially under the European feudal system, feoffment or enfeoffment was the deed by which a person was given land in exchange for a pledge of service. This mechanism was later used to avoid restrictions on the passage of t ...

ed" Spike Island. There are no further recorded changes in ownership until 1427. In this year, records suggest that William, son of John Reych, granted to John Pyke, ''amongst other lands and premises, the lands of Innyspyge, in the Comte Cork''. In 1490, Thomas Pyke granted to Maurice Ronan of Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork (city), Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a populatio ...

, his holdings in Spike Island. In the 17th century, the island was in the possession of the Roche and Galwey families until the rebellion of 1641, when these families forfeited possession of the island. Although this forfeiture was reversed on the accession of King Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651 and King of England, Scotland, and King of Ireland, Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest su ...

in 1660, they did not regain possession.

In 1698, the island was in the possession of Arnold Joost van Keppel, 1st Earl of Albemarle, who had accompanied William of Orange to England in 1688. In 1698, he conveyed the island to William Smith of Ballymore on the Great Island. In the 1770s, the island was in the hands of Nicholas Fitton. It would seem that the government leased part of the island for fortifications in the 1770s while the owner remained in residence, the house only being demolished during the construction of the present fort. Eventually, the entire island was rented.

Military use and fortification

It was possibly used by smugglers for a time, and a map of circa 1600 clearly shows some form of fortified tower on the island similar to a depiction of

It was possibly used by smugglers for a time, and a map of circa 1600 clearly shows some form of fortified tower on the island similar to a depiction of Belvelly Castle

Belvelly Castle is a 14th or 15th-century tower house in County Cork, Ireland. It is situated next to the small village of Belvelly, opposite and overlooking the only road bridge connecting Fota Island to Great Island (on which the town of Cobh ...

on the Great Island

Great Island () is an island in Cork Harbour, at the mouth of the River Lee and close to the city of Cork, Ireland. The largest town on the island is Cobh (called Queenstown from 1849 to 1920). The island's economic and social history has hist ...

also shown. The island's location at the entrance to Cork Harbour meant that the island held strategic importance. It was a significant site in the French intervention following the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

(1689).

Temporary fortification

The first artillery fortification on the island was built in 1779. Its construction was prompted by the outbreak of theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

in 1775, and in particular by the entry of France (1778) and Spain (1779) into the war on the American side. Cork Harbour was used as an assembly point for convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s to the Americas and at one point more than 400 vessels were assembled in the harbour. Additionally, Cork was a source of supplies for the British forces operating in the West Indies and North America. There was, therefore, a need to protect the harbour from potential attackers. The Spike Island Battery was a temporary work and armed with eighteen 24 pounder cannon moved from Cobh Fort. After the Treaty of Paris ended the war in 1783, this temporary work was demolished.

Fort Westmorland

In 1789, Colonel Charles Vallancey of the Corps of Irish Engineers, who had been made responsible for the fortification of the harbour during the American war, persuaded the then Lord LieutenantJohn Fane, 10th Earl of Westmorland

John Fane, 10th Earl of Westmorland, (1 June 175915 December 1841), styled Lord Burghersh between 1771 and 1774, was a British Tory politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, who served in most of the cabinets of the period, primari ...

to allow the construction of a permanent fortification on Spike Island. This work was undertaken by the Irish Board of Ordnance

The Board of Ordnance in the Kingdom of Ireland (1542–1800) performed the equivalent duties of the British Board of Ordnance: supplying arms and munitions, overseeing the Royal Irish Artillery and the Irish Engineers, and maintaining the fort ...

. In October 1790, the Earl visited the island and named the incomplete structure Fort Westmorland. In 1793, France declared war on Britain and a conflict began which, with one interlude, occupied the next two decades.

In 1794, on the departure of Westmorland, his successor as Lord Lieutenant, likely William Fitzwilliam, 4th Earl Fitzwilliam

William Wentworth-Fitzwilliam, 4th Earl Fitzwilliam (30 May 1748 – 8 February 1833), styled Viscount Milton until 1756, was a British Whig statesman of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In 1782 he inherited the estates of his uncle Cha ...

, halted construction of Fort Westmorland. Eventually, Vallancey was allowed to continue but the fort was still incomplete in 1797. It was, however, completed by 1802, as a plan of that date shows. By 1800, this fort was armed with three 13-inch, two 10-inch, two 8-inch and six 5.5-inch mortars

Mortar may refer to:

* Mortar (weapon), an indirect-fire infantry weapon

* Mortar (masonry), a material used to fill the gaps between blocks and bind them together

* Mortar and pestle, a tool pair used to crush or grind

* Mortar, Bihar, a village i ...

, 29 24-pounder guns, two 12-pounder guns and twelve 6-pounder cannon. Also included were two 6-pounder field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances (field artillery ...

s and two 5.5-inch howitzer

The howitzer () is an artillery weapon that falls between a cannon (or field gun) and a mortar. It is capable of both low angle fire like a field gun and high angle fire like a mortar, given the distinction between low and high angle fire break ...

s.

New fortress

The defences of Cork Harbour faced two threats. Firstly an attack by warships forcing entry into the harbour, either in a raid to destroy shipping or to effect a landing of troops. Secondly they faced the threat of attack from the land by forces which had been landed at an undefended point along the coast. Just such a landing had been attempted by the French atBantry Bay

Bantry Bay () is a bay located in County Cork, Ireland. The bay runs approximately from northeast to southwest into the Atlantic Ocean. It is approximately 3-to-4 km (1.8-to-2.5 miles) wide at the head and wide at the entrance.

Geograp ...

in 1796 with a force of 15,000 men. While unsuccessful, the attempt greatly alarmed the military. Vallancey was of the belief that had the French actually landed, they would have taken the Cork Harbour forts, including Fort Westmoreland.

In 1802, General

In 1802, General John Hope, 4th Earl of Hopetoun

General John Hope, 4th Earl of Hopetoun, (17 August 1765 – 27 August 1823), known as The Honourable John Hope from 1781 to 1814 and as Lord Niddry from 1814 to 1816, was a Scottish politician and British Army officer.

Military career

Hopetoun ...

, recommended that a major fortress be constructed on Spike Island, capable of holding 2,000 to 3,000 men. He considered Spike Island was "the true point of defence" for Cork Harbour. Lieutenant General David Dundas was consulted by the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of List of English monarchs, English (later List of British monarchs, British) monarchs ...

, Commander in Chief, who also recommended that a fortress should be erected on Spike Island. William Twiss of the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

concurred.

In 1801, the Acts of Union came into force and responsibility for fortifications in Ireland passed from the Irish Board of Ordnance, which was abolished, to the Board of Ordnance

The Board of Ordnance was a British government body. Established in the Tudor period, it had its headquarters in the Tower of London. Its primary responsibilities were 'to act as custodian of the lands, depots and forts required for the defence ...

in London. It was the job of this board to implement the decision to erect the fortress and it fell to Charles Holloway, Commanding Engineer Cork District, to begin the works. In 1804, the Hampshire Chronicle reported that the overall height of Spike island had been reduced by 25 feet and the spoil used as infill to create a level foundation. The same paper reported that, on 6 June 1804, General Sir Eyre Coote had laid the foundation stone of the new fortress.

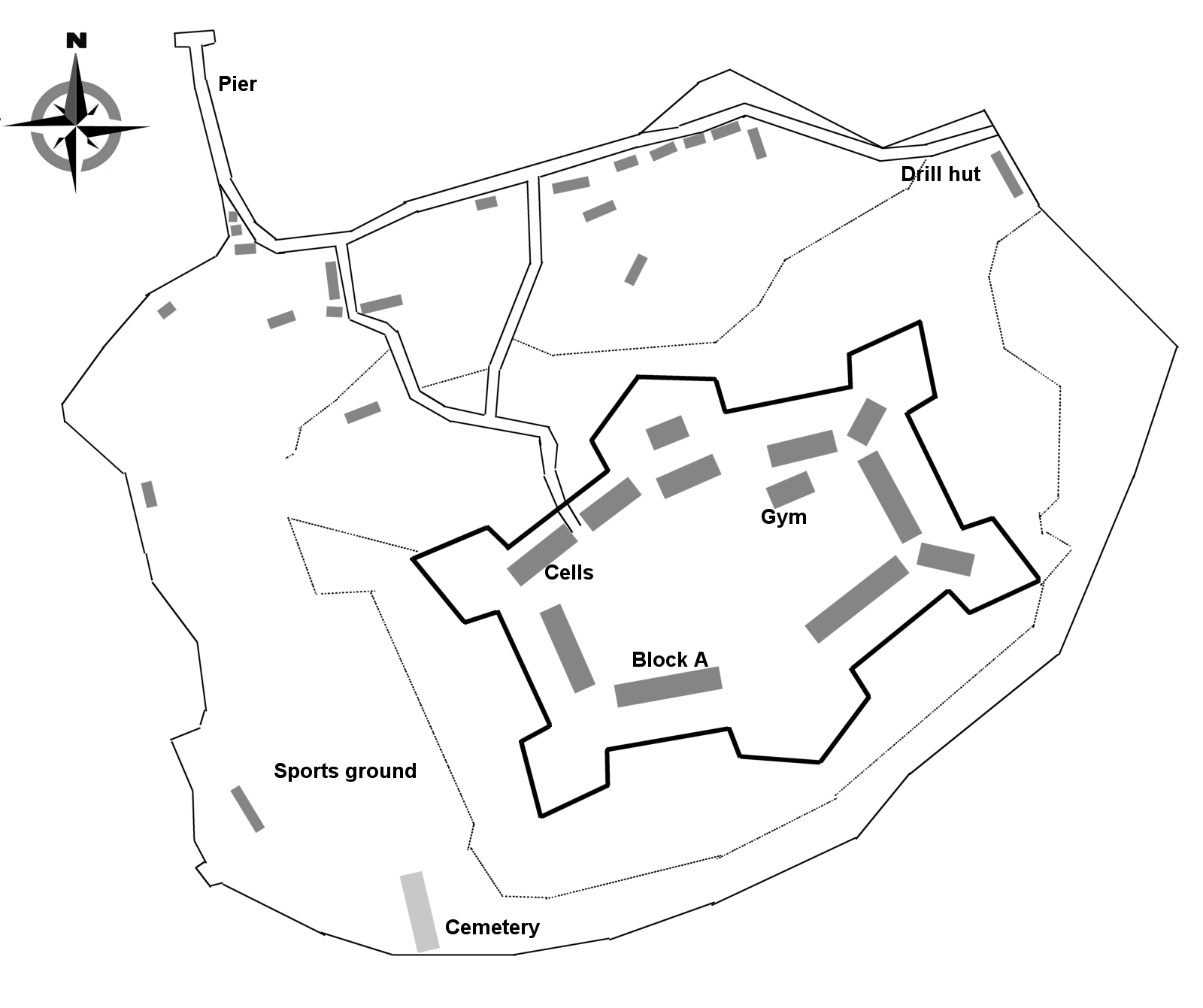

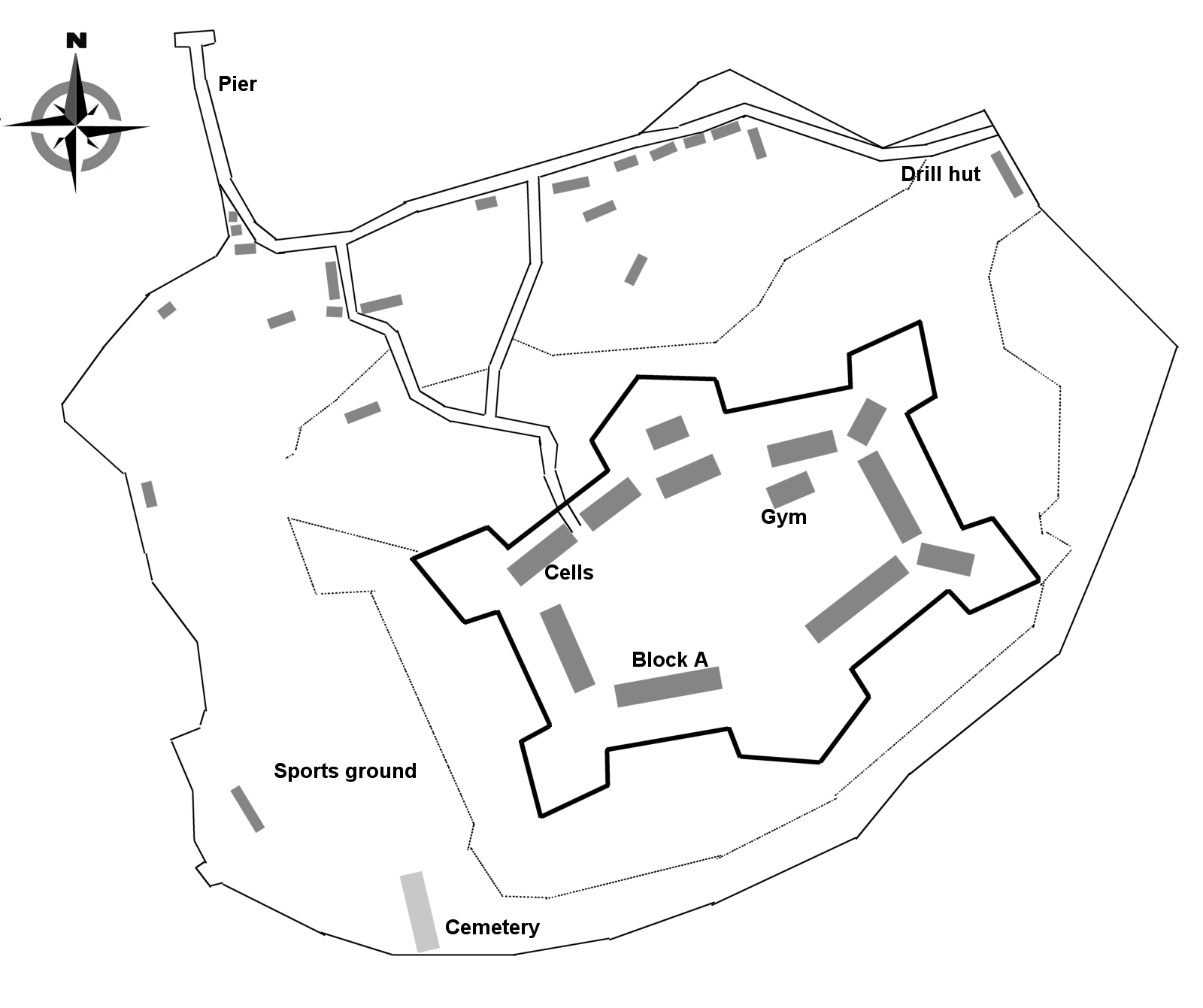

Two alternative proposals had been made for accommodation within the fort. One envisaged six barrack blocks, one of which was actually constructed in the fort, this being the officers mess block, The ground floor of these blocks consisted of a series of bombproof brick vaulted rooms. The first floor was slate-roofed and open to destruction in the event of a bombardment. The second proposal was for six sets of bombproof casemates set into the ramparts. Two such sets of casemates were actually constructed, these being the north-east and north-west casemates. The second accommodation block to be constructed, the A Block, shows a divergence from the original plan in that the bombproofing is incorporated into the roof. The ground floor of a third block, the B Block, was intended to follow the design of the A block, was erected before the first phase of construction ended (circa 1817). The four

Two alternative proposals had been made for accommodation within the fort. One envisaged six barrack blocks, one of which was actually constructed in the fort, this being the officers mess block, The ground floor of these blocks consisted of a series of bombproof brick vaulted rooms. The first floor was slate-roofed and open to destruction in the event of a bombardment. The second proposal was for six sets of bombproof casemates set into the ramparts. Two such sets of casemates were actually constructed, these being the north-east and north-west casemates. The second accommodation block to be constructed, the A Block, shows a divergence from the original plan in that the bombproofing is incorporated into the roof. The ground floor of a third block, the B Block, was intended to follow the design of the A block, was erected before the first phase of construction ended (circa 1817). The four magazine

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

s were also constructed around this time. A large workforce was employed in the construction, and included both troops and civilian workmen.

Later use

Later aprison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where Prisoner, people are Imprisonment, imprisoned under the authority of the State (polity), state ...

and convict depot, the island was used to house convicts prior to penal transportation

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies bec ...

. Opened in 1847 to deal with growing number of convictions for theft during the Great Famine, the prison grew into what "for a few years in the mid-19th century .was probably .the biggest prison in the British Empire". It later gained a reputation as "Ireland's Alcatraz

Alcatraz Island () is a small island about 1.25 miles offshore from San Francisco in San Francisco Bay, California, near the Golden Gate Strait. The island was developed in the mid-19th century with facilities for a lighthouse, a military fo ...

".

Spike Island was home to Ellen (Nellie) Organ who gained special permission to take First Communion

First Communion is a ceremony in some Christian traditions during which a person of the church first receives the Eucharist. It is most common in many parts of the Latin tradition of the Catholic Church, Lutheran Church and Anglican Communion (ot ...

shortly before her death at the age of 4. On hearing her story, the pope lowered the age at which communion could be taken, from 12 to 7.

The island remained in use as a garrison and prison through the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

, when IRA prisoners were held there. Richard Barrett was among those detained there, but escaped during the truce of 1921. Over 1400 men were held on the island at its peak until the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

.

On 6 December 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was concluded. It provided for the establishment of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

which happened on 6 December 1922. The Treaty included provisions by which the British would retain sovereignty over three strategically important ports known as the Treaty ports

Treaty ports (; ) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Qing dynasty of China (before th ...

, one of which is described in the Treaty as:

Accordingly, even after the establishment of the Irish Free State, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

continued to maintain its presence at Spike Island. Spike Island remained under British sovereignty until 11 July 1938 when pursuant to the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement of 25 April 1938, the territory was ceded to Ireland. The handover ceremonies were attended by senior military and political figures, including Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

and Frank Aiken

Francis Thomas Aiken (13 February 1898 – 18 May 1983) was an Irish revolutionary and politician. He was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army, chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army (1922–1969), Anti-Treaty IRA at the end of the I ...

.

History since handover

Following its handover to Ireland, the island's installations were renamed Fort Mitchel - after

Following its handover to Ireland, the island's installations were renamed Fort Mitchel - after John Mitchel

John Mitchel (; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist writer and journalist chiefly renowned for his indictment of British policy in Ireland during the years of the Great Famine (Ireland), Great Famin ...

, nationalist activist and political journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

who was held on the island for a time. (Similar Treaty Port fortifications at '' Fort Camden'' and '' Fort Carlisle'' were similarly renamed to ''Fort Meagher'' and ''Fort Davis'' respectively.)

The island remained the site of a prison and military base (for the regular Irish Army

The Irish Army () is the land component of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Defence Forces of Republic of Ireland, Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. ...

, the FCÁ and later the Navy) for some time. Late into the 20th century, it was used as a youth correctional facility. On 1 September 1985 inmates rioted and, as a subsequent Dáil committee reported, "civilians, prison officers and the Gardaí on the Island were virtual prisoners of the criminals". During the riot, one of the accommodation blocks, Block A, caught fire and is known as the Burnt Block. This prison facility closed in 2004.

The island also had a small civilian population; a small school, church and ferry (launch) service to Cobh

Cobh ( ,), known from 1849 until 1920 as Queenstown, is a seaport town on the south coast of County Cork, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. With a population of 14,148 inhabitants at the 2022 census of Ireland, 2022 census, Cobh is on the south si ...

served the population. The civilian population has since left the island.

Demographics

Tourism development

In May 2006, the then Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell, announced plans to build a new prison on the island. However, in January 2007, it was decided to explore an alternative site for the new prison, and a local task group was set up to re-open Spike Island as a historical tourist site. In 2009, it was announced that ownership of the island would be transferred, free of charge, to

In May 2006, the then Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell, announced plans to build a new prison on the island. However, in January 2007, it was decided to explore an alternative site for the new prison, and a local task group was set up to re-open Spike Island as a historical tourist site. In 2009, it was announced that ownership of the island would be transferred, free of charge, to Cork County Council

Cork County Council () is the local authority of County Cork, Ireland. As a county council, it is governed by the Local Government Act 2001, as amended. The council is responsible for housing and community, roads and transportation, urban pl ...

to enable its development as a tourist attraction. The Council formed a steering group to explore how Spike Island might be developed as a tourist site, and the Council subsequently licensed operators to give guided tours of the island.

Since 2015, tours depart from Cobh during the summer, taking in the fort, prison cells, gun emplacements, and key points of interest. Following additional €5.5m investment by Cork County Council, and Fáilte Ireland

Fáilte Ireland is the operating name of the National Tourism Development Authority of Ireland. This authority was established under the National Tourism Development Authority Act of 2003 to replace and build upon the functions of Bord Fáilte, i ...

, additional attractions and facilities were opened for the summer 2016 season. As well as the previously opened buildings and 6-inch gun emplacements, as of summer 2016, visitors to the "Fortress Spike Island" cultural heritage attraction can also tour the "punishment block", the 1980s cells (which include an exhibition on the 1985 Spike Island riot), the recreation of the hull of a "transportation ship", and an interpretative installation on John Mitchel, for whom the fort is named.

In September 2017, at the World Travel Awards, Spike Island was named "Europe's Leading Tourist Attraction".

References

External links

*Irish National Inventory of Architectural Heritage - Architectural detail on structures on the island

{{County Cork Islands of County Cork Cobh Former populated places in Ireland Prison islands Defunct prisons in the Republic of Ireland Tourist attractions in County Cork