Social History Of The United Kingdom (1979–present) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Host: James Lipton. ''

House prices tripled in the 20 years between 1995 and 2015. Growth was almost continuous during the period, save for a two-year period of decline around 2008 as a result of the

House prices tripled in the 20 years between 1995 and 2015. Growth was almost continuous during the period, save for a two-year period of decline around 2008 as a result of the

excerpt and text search

*

excerpt and text search

*

online review

* * *

excerpt and text search

* * Davie, Grace. ''Religion in Britain since 1945: Believing without belonging'' (Blackwell, 1994) * 310 pp. * 200+ short scholarly essays; covers 20th century * Gilley, Sheridan, and W. J. Sheils. ''A History of Religion in Britain: Practice and Belief from Pre-Roman Times to the Present'' (1994) 608pp * * * Hastings, Adrian. ''A History of English Christianity: 1920-1985'' (1986) 720pp; a major scholarly survey * Hilton, Matthew. ''Smoking in British Popular Culture 1800-2000: Perfect Pleasures'' (Manchester UP, 2000). * Leventhal, F.M. ''Twentieth-Century Britain: An Encyclopedia'' (2nd ed. 2002) 640pp; short articles by scholars * history of political ideas * * * * Panton, Kenneth J. and Keith A. Cowlard, eds. ''Historical Dictionary of the Contemporary United Kingdom'' (2008) 640 pp; biographies of people active 1979–2007 * Polley, Martin. ''Moving the Goalposts: A History of Sport and Society since 1945'' (1998

online

* Savage Mike. ''Identities and Social Change in Britain since 1940: The Politics of Method'' (Oxford UP, 2010) * essays by scholar

excerpt and text search

* *

excerpt and text search

* Booker, Christopher. ''The Seventies: The Decade That Changed the Future'' (1980) * Garnett, Mark. ''From Anger to Apathy: The Story of Politics, Society and Popular Culture in Britain since 1975''(2008

excerpt

* Marr, Andrew. ''A History of Modern Britain'' (2009); covers 1945–2005. * Marr, Andrew. ''Elizabethans: How Modern Britain Was Forged'' (2021), covers 1945 to 2020.. * Sampson, Anthony. ''The Essential Anatomy of Britain: Democracy in Crisis'' (1992) online free * Sampson, Anthony. ''Who Runs This Place?: The Anatomy of Britain in the 21st Century'' (2005) * Bering, Henrik. "Taking the great out of Britain". ''Policy Review'', no. 133, (2005), p. 88+

online review

* Stewart, Graham. ''Bang! A History of Britain in the 1980s'' (2013

excerpt and text search

560pp * Turner, Alwyn W. ''Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s'' (2008) ** Turner, Alwyn W. ''Rejoice! Rejoice!: Britain in the 1980s'' (2013). ** Turner, Alwyn W. ''A Classless Society: Britain in the 1990s'' (2013); 650 pp * Weight, Richard. ''MOD: From Bebop to Britpop, Britain's Biggest Youth Movement'' (2013), by a scholar * Whitehead, Phillip. ''The Writing on the Wall: Britain in the Seventies'' (Michael Joseph, 1985); 456 pp * Wilson, A. N. ''Our Times: The Age of Elizabeth II'' (2009); by a scholar

excerpt and text search

762 pp of social statistics * Wybrow, Robert J. ''Britain Speaks Out, 1937–87'' (1989), summaries of Gallup public opinion polls.

Online history of National Health Service by Geoffrey Rivett (2025)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Social history of the United Kingdom (1979-present) 20th century in the United Kingdom 21st century in the United Kingdom Contemporary British history Social history of the United Kingdom

social history

Social history, often called history from below, is a field of history that looks at the lived experience of the past. Historians who write social history are called social historians.

Social history came to prominence in the 1960s, spreading f ...

of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

(1979–present) began with Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

(1979–1990) entering government and rejecting the post-war consensus

The post-war consensus, sometimes called the post-war compromise, was the economic order and social model of which the major political parties in post-war Britain shared a consensus supporting view, from the end of World War II in Europe in 1 ...

in the 1980s. She privatised most state-owned industries and worked to weaken the power and influence of the trade unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

. The party remained in government throughout most of the 1990s albeit with growing internal difficulties under the leadership of Prime Minister John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

(1990–1997).

The "New Labour

New Labour is the political philosophy that dominated the history of the British Labour Party from the mid-late 1990s to 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The term originated in a conference slogan first used by the ...

" premiership of Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

(1997–2007) accepted many of Thatcher's economic policies, but he presided over a period of relative economic prosperity. Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

, the most prosperous and the last significant overseas territory was handed back to China in 1997, ending 156 years of British rule and the symbolic end of the empire. Blair's government grew unpopular after 2002, in part due to Britain's participation in the war on terror and, most controversially, the Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

. The brief premiership of Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. Previously, he was Chancellor of the Ex ...

(2007–2010) was predominantly defined by a series of crises including the 2008 financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), was a major worldwide financial crisis centered in the United States. The causes of the 2008 crisis included excessive speculation on housing values by both homeowners ...

and its consequences

Consequence may refer to:

Philosophy, science and social sciences

* Logical consequence, also known as a ''consequence relation'', or ''entailment''

* Consequent, in logic, the second half of a hypothetical proposition or consequences

* Consequent ...

.

The Coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

(2010–2015) formed by David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

and Nick Clegg

Sir Nicholas William Peter Clegg (born 7 January 1967) is a British retired politician and media executive who served as Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2015 and as Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 2007 to 2015. H ...

introduced a deficit reduction programme primarily via cuts to public spending. In 2014, a referendum on Scottish Independence was held where the electorate in Scotland voted by 55/45% to remain within the United Kingdom. Winning a majority in 2015, the conservatives held a referendum on the UK's membership of the EU the following year where the UK voted by 52/48% to leave the organisation. The premiership of Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Baroness May of Maidenhead (; ; born 1 October 1956), is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served as Home Secretar ...

(2016–2019) was defined by the UK's withdrawal from the EU which was completed under the premiership of Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

(2019–2022); his government was also defined by the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

.

Other shifts in the UK during the late 20th and early 21st century include the rise of the internet with computerised technology taking an ever greater role in most aspects of life, rising enrolment in further

Further or furthur, alternatively farther, may refer to:

* ''Furthur'' (bus), the Merry Pranksters' psychedelic bus

*Further (band), a 1990s American indie rock band

*Furthur (band)

Furthur was an American rock band founded in 2009 by former G ...

and higher education among older adolescents and young adults, as well as a diminishing interest in politics with 21st century elections seeing consistently lower turnout than their 20th century counterparts. The New Labour era and current period of consecutive conservative or conservative led governments have seen the devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territori ...

of substantial powers to Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and, to a lesser extent, parts of England.

Thatcher's Britain

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

was the dominant political force of the late twentieth century, often compared to Churchill and David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

for her transformative agenda commonly referred to as "Thatcherism

Thatcherism is a form of British conservative ideology named after Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher that relates to not just her political platform and particular policies but also her personal character a ...

". She was Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990, and prime minister from 1979 to 1990. She was often called the "Iron Lady" for her uncompromising politics and leadership style.

Political analyst Dennis Kavanagh

Dennis Kavanagh (born 27 March 1941) is a British political analyst and since 1996 has been Professor of Politics at the University of Liverpool, and now Emeritus Professor. He has written extensively on post- war British politics. With David Bu ...

concludes that the "Thatcher Government produced such a large number of far-reaching changes across much of the policy spectrum, that it passes 'reasonable' criteria of effectiveness, radicalism, and innovation".

The Labour Party under James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the L ...

(1976–79) contested the 1979 general election as unemployment passed the 1,000,000 mark and trade unions became more aggressive. The Conservatives used a highly effective poster created by advertisers Saatchi & Saatchi

Saatchi and Saatchi is a British multinational communications and advertising agency network with 114 offices in 76 countries and over 6,500 staff. It was founded in 1970 and is currently headquartered in London. The parent company of the agency ...

, showing an unemployment queue snaking into the distance, carrying the caption "Labour isn't working". The Conservatives received 43.9% of the vote and 339 seats to Labour's 269, for an overall majority of 44 seats at the 1979 general election. Labour was weakened by the steady long-term decline in the proportion of manual workers in the electorate. Twice as many manual workers normally voted Labour as voted Conservative, but they now constituted only 56% of the electorate. When the Labour Party led by Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

narrowly won the 1964 general election, manual workers had accounted for 63%. Furthermore, they were beginning to turn against the trade unions – alienated, perhaps, by the difficulties of the winter of 1978–9. In contrast, Conservative policies stressed wider home ownership, which Labour refused to match. Thatcher did best in districts where the economy was relatively strong and was weaker where it was contracting.

Thatcherism

As prime minister, she implemented policies focused oneconomic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism ...

, using populism

Populism is a essentially contested concept, contested concept used to refer to a variety of political stances that emphasize the idea of the "common people" and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite. It is frequently a ...

, and pragmatism, known as Thatcherism

Thatcherism is a form of British conservative ideology named after Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher that relates to not just her political platform and particular policies but also her personal character a ...

. Thatcher introduced a series of political and economic initiatives intended to reverse high unemployment and Britain's struggles in the wake of the Winter of Discontent

The Winter of Discontent was the period between late September 1978 and February 1979 in the United Kingdom characterised by widespread strikes by private, and later public sector trade unions demanding pay rises greater than the limits Prime ...

and an ongoing recession. Her political philosophy and economic policies emphasised deregulation

Deregulation is the process of removing or reducing state regulations, typically in the economic sphere. It is the repeal of governmental regulation of the economy. It became common in advanced industrial economies in the 1970s and 1980s, as a ...

(particularly of the financial sector), flexible labour markets, the privatisation of state-owned companies

A state-owned enterprise (SOE) is a business entity created or owned by a national or local government, either through an executive order or legislation. SOEs aim to generate profit for the government, prevent private sector monopolies, provide goo ...

and reducing the power and influence of trade unions. Due to recession and high unemployment, Thatcher's popularity during her first years in office waned until the beginning of 1982, a few months before the Falklands War

The Falklands War () was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British Overseas Territories, British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and Falkland Islands Dependenci ...

. The afterglow of her victory at that war produced a resounding victory at the polls. She was re-elected in 1983 with an increased majority.

Privatisation was an enduring legacy of Thatcherism; it was accepted by the future Labour ministry of Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

. Her policy was to privatise nationalised corporations (such as telephone and aerospace firms). She sold public housing to tenants, all on favourable terms. The policy developed an important electoral dimension during the second Thatcher government (1983–87). It involved more than denationalisation: wider share ownership was the second plank of the policy. Thatcher advocated an "enterprise society" in Britain, especially in widespread share-ownership, personal ownership of council houses, the marginalisation of trade unions and the expansion of private healthcare. These policies transformed many aspects of British society.

Thatcher was re-elected for a third term in 1987

Events January

* January 1 – Bolivia reintroduces the Boliviano currency.

* January 2 – Chadian–Libyan conflict – Battle of Fada: The Military of Chad, Chadian army destroys a Libyan armoured brigade.

* January 3 – Afghan leader ...

, although Labour made gains under the new leadership of Neil Kinnock

Neil Gordon Kinnock, Baron Kinnock (born 28 March 1942) is a Welsh politician who was Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1983 Labour Party le ...

compared to their landslide defeat at the previous election. During this period, her support for a Community Charge

The Community Charge, colloquially known as the Poll Tax, was a system of local taxation introduced by Margaret Thatcher's government whereby each taxpayer was taxed the same fixed sum (a "poll tax" or " head tax"), with the precise amount bei ...

(popularly referred to as the "poll tax") was widely unpopular (especially in Scotland where the tax was enforced one year earlier than the rest of the country) and her negative views on the European Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

were not shared by others in her Cabinet. She lost support from Conservative MPs and resigned as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party in November 1990.

Cultural movements

Environmentalism as a major public issue was brought to the forefront by Thatcher in 1988, when she included a manifesto warning about climate change. Theenvironmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related aspects of green ideology and politics, ecolog ...

movements of the 1980s reduced the emphasis on intensive farming

Intensive agriculture, also known as intensive farming (as opposed to extensive farming), conventional, or industrial agriculture, is a type of agriculture, both of arable farming, crop plants and of Animal husbandry, animals, with higher levels ...

, and promoted organic farming

Organic farming, also known as organic agriculture or ecological farming or biological farming,Labelling, article 30 o''Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2024 on organic production and labelling of ...

and conservation

Conservation is the preservation or efficient use of resources, or the conservation of various quantities under physical laws.

Conservation may also refer to:

Environment and natural resources

* Nature conservation, the protection and manage ...

of the countryside.

Protestant religious observance declined notably in Britain during the second half of the twentieth century. Catholicism (based on the Irish elements) held its own, while Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

grew rapidly due to immigration from Asia and the Middle East as well as higher birth rates from that sector of the general population. Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

attendance particularly dropped, although charismatic churches

() is a personal quality of magnetic charm, persuasion, or appeal.

In the fields of sociology and political science, psychology, and management, the term ''charismatic'' describes a type of leadership.

In Christian theology

Christian t ...

like Elim and AOG grew. The movement to Keep Sunday Special

Keep Sunday Special is a British campaign group set up in 1985 by Michael Schluter to oppose plans to introduce Sunday trading in England and Wales (there are different arrangements in Scotland and Northern Ireland). The Keep Sunday Special camp ...

seemed to have lost at the beginning of the 21st century.

LGBT rights under Thatcher

Although "homosexual acts" had been partially decriminalised for consenting men over the age of 21 inEngland and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Th ...

in 1967 (Sexual Offences Act 1967

The Sexual Offences Act 1967 (c. 60) is an act of Parliament in the United Kingdom. It legalised homosexual acts in England and Wales, on the condition that they were consensual, in private and between two men who had attained the age of 21. ...

), it was not until the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1980

The Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1980 (c. 62) is an act of Parliament in the United Kingdom. Most of the act's provisions were merely a consolidation of already existing legislation, and as such subject to little controversy, with the notable ...

that the same happened in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

. That same year, the documentary ''A Change of Sex

''A Change of Sex'' is a multi-part television documentary about English trans woman Julia Grant. The first chapter, initially titled ''George'', premiered on BBC2 in 1979. It is one of the first documentary films about transgender issues.

BBC2 ...

'' aired on BBC2

BBC Two is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's second flagship channel, and it covers a wide range of subject matter, incorporating genres such as comedy, drama and ...

, which enabled viewers to follow the social and medical transition of Julia Grant

Julia Boggs Grant (née Dent; January 26, 1826 – December 14, 1902) was the first lady of the United States and wife of President Ulysses S. Grant. As first lady, she became the first woman in the position to write a memoir. Her memoirs, '' Th ...

, and provided a snapshot of the Gender Identity Clinic at Charing Cross Hospital

Charing Cross Hospital is district general hospital and teaching hospital located in Hammersmith in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. The present hospital was opened in 1973, although it was originally established in 1818, approxim ...

in London. The Self Help Association for Transsexuals (SHAFT) was also formed as an information collecting and disseminating body for transgender

A transgender (often shortened to trans) person has a gender identity different from that typically associated with the sex they were sex assignment, assigned at birth.

The opposite of ''transgender'' is ''cisgender'', which describes perso ...

people, The first Black Gay and Lesbian Group was formed in the UK. and Lionel Blue

Lionel Blue (né Bluestein; 6 February 1930 – 19 December 2016) was a British Reform Judaism, Reform rabbi, journalist and broadcaster, described by ''The Guardian'' as "one of the most respected religious figures in the UK". He was best know ...

became the first British rabbi to come out as gay. The UK's first television series specifically aimed at a gay audience was broadcast on London Weekend Television

London Weekend Television (LWT; now part of the non-franchised ITV London region) was the ITV (TV network), ITV network franchise holder for Greater London and the Home Counties at weekends, broadcasting from Fridays at 5.15 pm (7:00&nbs ...

, called ''Gay Life

Gay Life was a weekly newspaper about gay culture published by the LGBT Community Center of Baltimore and Central Maryland. It was distributed in Baltimore, Maryland and throughout the Mid-Atlantic region.

History

In September 1979, the GCCB ...

''.

In 1981, the European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The court hears applications alleging that a co ...

in ''Dudgeon v United Kingdom

''Dudgeon v United Kingdom'' (1981) was a European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) case, which held that Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which criminalised male homosexual acts in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, breached ...

'' struck down Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

's criminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults the Homosexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 1982

The Homosexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 1982, No. 1536 (N.I. 19), is an Order in Council which decriminalized homosexual acts between consenting adults in Northern Ireland. The Order was adopted as a result of a European Court of Human R ...

later partially decriminalised "homosexual acts" in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

. The next year, Chris Smith, says: "My name is Chris Smith. I'm the Labour MP for Islington South and Finsbury

Islington South and Finsbury is a constituency created in 1974 and represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 2005 by Emily Thornberry of the Labour Party. Thornberry served as Shadow Foreign Secretary from 2016 until 2020 a ...

, and I'm gay", making him the first openly out gay politician in the UK parliament. The Politics of Bisexuality conference in 1984 signaled the growth of separate bisexual community organising. Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners

Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) was an alliance of lesbians and gay men who supported the National Union of Mineworkers (Great Britain), National Union of Mineworkers during the year-long UK miners' strike (1984–1985), strike of 1 ...

, a campaign of LGBT support for striking workers in the miners' strike

The following is a list of miners' strikes. Miners' strikes are when miners conduct strike actions.

See also

*List of strikes

*History of coal mining in the United States

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Miners' strikes

Miners' labor disputes, ...

of 1984 and 1985, was launched. In 1988, Princess Margaret

Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon (Margaret Rose; 21 August 1930 – 9 February 2002) was the younger daughter of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. She was the younger sister and only sibling of Queen Elizabeth II.

...

opened the UK's first residential support centre for people living with HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the im ...

and AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

in London at London Lighthouse.

In July 1990, following the murders in a short period of time, of four gay men, hundreds of lesbians and gay men marched from the park where Boothe had been killed to Ealing Town Hall

Ealing Town Hall is a municipal building in New Broadway, Ealing, London, England. It is a Grade II listed building.

History

The building was commissioned to replace the old town hall, designed by the town surveyor, Charles Jones, in The Mall ...

and held a candlelit vigil. The demonstration led to the formation of OutRage, who called for the police to start protecting gay men instead of arresting them. In September, lesbian and gay police officers established the Lesbian and Gay Police Association (Lagpa/GPA). The first gay pride

In the context of LGBTQ culture, pride (also known as LGBTQ pride, LGBTQIA pride, LGBT pride, queer pride, gay pride, or gay and lesbian pride) is the promotion of the rights, self-affirmation, dignity, Social equality, equality, and increas ...

event was held in Manchester. ''Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit

''Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit'' is a novel by Jeanette Winterson published in 1985 by Pandora Press. It is a coming-of-age story about a lesbian who grows up in an English Pentecostal community. Key themes of the book include transition from ...

'' by Jeanette Winterson

Jeanette Winterson (born 27 August 1959) is an English author.

Her first book, '' Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit'', was a semi-autobiographical novel about a lesbian growing up in an English Pentecostal community. Other novels explore gender ...

, a semi-autobiographical screenplay about her lesbian life was shown on BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

television. Justin Fashanu

Justinus Soni "Justin" Fashanu ( ; 19 February 1961 – 2 May 1998) was an English footballer who played for a variety of clubs between 1978 and 1997. He was known by his early clubs to be gay, and came out publicly later in his career, becoming ...

became the first professional footballer to come out in the press (he subsequently committed suicide). The Crown Dependency

The Crown Dependencies are three offshore island territories in the British Islands that are self-governing possessions of the British Crown: the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Bailiwick of Jersey, both located in the English Channel and toge ...

of Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

decriminalised homosexuality.

= AIDS

= The first UK case ofAIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

was recorded when a 49-year-old man was admitted to Royal Brompton Hospital

Royal Brompton Hospital is the largest specialist heart and lung medical centre in the United Kingdom. It is managed by Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust.

History Consumption in the 19th century

In the 19th century, consumption was a co ...

in London suffering from PCP ( Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia). He died ten days later. Terry Higgins died of AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

in St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. Administratively part of the Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, together with Guy's Hospital, Evelina London Children's Hospital, Royal Brompton Hospita ...

in London, and his friends and partner Martyn Butler set up the Terry Higgins Trust (which became the Terrence Higgins Trust

Terrence Higgins Trust is a British charity that campaigns about and provides services relating to HIV and sexual health. In particular, the charity aims to end the transmission of HIV in the UK; to support and empower people living with HIV, to ...

), the first UK AIDS charity. In 1983, Britain reported 17 cases of AIDS; gay men were asked not to donate blood. The next year, Britain reported 108 cases of AIDS with 46 deaths from the disease.

In 1985, AIDS hysteria grew in the UK when passengers on the ''Queen Elizabeth 2

''Queen Elizabeth 2'' (''QE2'') is a retired British ocean liner. Built for the Cunard Line, the ship was operated as a transatlantic liner and cruise ship from 1969 to 2008. She was laid up until converted into a floating hotel, operating sin ...

'' curtailed their holiday after a person with AIDS was discovered on board. Cunard

The Cunard Line ( ) is a British shipping and an international cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its four ships have been r ...

were criticised in the press for trying to cover this up. A London support group Body Positive was set up that year as a self-help group for people affected by HTLV-3 and AIDS. Health Minister

A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare spending and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental heal ...

, Kenneth Clarke

Kenneth Harry Clarke, Baron Clarke of Nottingham (born 2 July 1940) is a British politician who served as Home Secretary from 1992 to 1993 and Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1993 to 1997. A member of the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative ...

, enacted powers to detain people with AIDS in hospital against their will, potentially preventing people coming forward for treatment. In 1987, the first UK specialist HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the im ...

ward was opened by Diana, Princess of Wales

Diana, Princess of Wales (born Diana Frances Spencer; 1 July 1961 – 31 August 1997), was a member of the British royal family. She was the first wife of Charles III (then Prince of Wales) and mother of Princes William, ...

; at the opening she made a point of not wearing protective gloves or a mask when she shook hands with the patients. AZT

Zidovudine (ZDV), also known as azidothymidine (AZT), was the first antiretroviral medication used to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS. It is generally recommended for use in combination with other antiretrovirals. It may be used to prevent vertica ...

, the first HIV drug to show promise of suppressing the disease was made available in the UK for the first time.

= Section 28

= In 1987, Thatcher said at the Conservative Party conference: "Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay". Backbench Conservative MPs and Peers had already begun a backlash against the promotion of homosexuality and, in December 1987, Clause 28 was introduced into a bill on local governance by Jill Knight,Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

MP for Birmingham Edgbaston

Birmingham Edgbaston is a constituency, represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 2017 by Preet Gill, a Labour Co-op MP.

The most high-profile MP for the constituency was former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (1937–19 ...

.

In 1988, Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988

The Local Government Act 1988 (c. 9) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was famous for its controversial section 28. This section prohibited local authorities from promoting, in a specified category of schools, "the teaching ...

enacted as an amendment to the United Kingdom's Local Government Act 1986, on 24 May 1988 stated that a local authority

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of governance or public administration within a particular sovereign state.

Local governments typically constitute a subdivision of a higher-level political or administrative unit, such a ...

"shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality" or "promote the teaching in any maintained school

English state-funded schools, commonly known as state schools, provide education to pupils between the ages of 3 and 18 without charge. Approximately 93% of English schoolchildren attend 24,000 such schools. Since 2008 about 75% have attained "a ...

of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship". Almost identical legislation was enacted for Scotland by the Westminster Parliament. Sir Ian McKellen

Sir Ian Murray McKellen (born 25 May 1939) is an English actor. He has played roles on the screen and stage in genres ranging from Shakespearean dramas and modern theatre to popular fantasy and science fiction. He is regarded as a British cu ...

came out

Coming out of the closet, often shortened to coming out, is a metaphor used to describe LGBTQ people's self-disclosure of their sexual orientation, romantic orientation, or gender identity.

This is often framed and debated as a privacy issue, ...

on BBC Radio 3

BBC Radio 3 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. It replaced the BBC Third Programme in 1967 and broadcasts classical music and opera, with jazz, world music, Radio drama, drama, High culture, culture and the arts ...

in response to the governments proposed Section 28

Section 28 refers to a part of the Local Government Act 1988, which stated that Local government in the United Kingdom, local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales "shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with t ...

in the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

."Ian McKellen."Host: James Lipton. ''

Inside the Actors Studio

''Inside the Actors Studio'' is an American talk show that airs on Ovation. The series premiered on June 12, 1994 on Bravo, airing for 22 seasons and was hosted by James Lipton from its premiere until 2018. It is taped at the Michael Schimmel ...

''. Bravo. 8 December 2002. No. 5, season 9. McKellen has stated that he was influenced in his decision by the advice and support of his friends, among them the gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late ...

author Armistead Maupin

Armistead Jones Maupin, Jr. ( ; born May 13, 1944) is an American writer notable for '' Tales of the City'', a series of novels set in San Francisco.

Early life

Maupin was born in Washington, D.C., to Diana Jane (Barton) and Armistead Jones Maup ...

. In 1989, the campaign group Stonewall UK

Stonewall Equality Limited, trading as Stonewall, is a lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBTQ) rights charity in the United Kingdom. It is the largest LGBT rights organisation in Europe.

Named after the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York C ...

was set up to oppose Section 28 and other barriers to equality.

Economic change

Household prosperity

From 1964 to 1996, income per head doubled, while ownership of various household goods significantly increased. By 1996, two-thirds of households owned cars, 82% had central heating, most people owned a VCR, and one in five houses had a home computer. In 1971, 9% of households had no access to a shower or bathroom, compared with only 1% in 1990; largely due to demolition or modernisation of older properties that lacked such facilities. In 1971, only 35% had central heating, while 78% enjoyed this amenity in 1990. By 1990, 93% of households had colour television, 87% had telephones, 86% had washing machines, 80% had deep-freezers, 60% had video-recorders and 47% had microwave ovens. Holiday entitlements became more generous. In 1990, nine out of ten full-time manual workers were entitled to more than four weeks of paid holiday a year, while twenty years previously; only two-thirds had been allowed three weeks or more.Anthony Sampson, ''The Essential Anatomy of Britain: Democracy in Crisis'' (1993) p 64 The post-war period also witnessed significant improvements in housing conditions. In 1960, 14% of British households had no indoor toilet, while in 1967; 22% of all homes had no basic hot water supply. By the 1990s, however almost all homes had these amenities together with central heating.Troubles of 1970s and after

= Deindustrialisation

= After 1973 Britain experienced considerabledeindustrialisation

Deindustrialization is a process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial capacity or activity in a country or region, especially of heavy industry or manufacturing industry.

There are different interpr ...

, especially in both heavy industry (such as mining and steel) and light manufacturing. New jobs appeared with either low wages, or with high skill requirements that the laid-off workers lacked. Jim Tomlinson agrees that deindustrialisation is a major phenomenon but argues that it represents a stepping stone in the country's economic development rather than decline or failure.

After 1960, British industries were troubled, a phenomenon sometimes known as the " British Disease". The railways were decrepit, more textile mills closed than opened, steel employment fell sharply and the automotive industry practically disappeared, apart from some luxury models. Deindustrialisation meant the closure of many operations in mining, heavy industry and manufacturing, with the resulting loss of high paid working-class jobs. A certain amount of turnover had always taken place, with newer businesses replacing older ones. However, the 1970s were different, with a worldwide energy crisis and a dramatic influx of low-cost manufactured goods from Asia leading to more closures and fewer openings. Major sectors were hit hard between 1966 and 1982, with a 60% decline in textiles, 53% in metal manufacture, 43% in mining, 38% in construction, and 35% in vehicles.

Coal mining quickly collapsed and practically disappeared in the 21st century. The consumption of coal, mostly for electricity—fell from 157,000,000 tonnes in 1970 to 37,000,000 tonnes in 2015, nearly all of it imported. Coal mining jobs fell from a peak of 1,191,000 in 1920 to 695,000 in 1956, 247,000 in 1976, 44,000 in 1993 to 2,000 in 2015. In the 1970s, manufacturing accounted for 25% of the economy. Total employment in manufacturing fell from 7.1 million in 1979 to 4.5 million in 1992 and only 2.7 million in 2016, when it accounted for 10% of the economy.

In Scotland, deindustrialisation took place rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s, as most of the traditional industries drastically shrank or completely closed. A new service-oriented economy emerged to replace them. In 1954, Scottish shipyards built 12% of the world's tonnage, falling to 1% in 1968. North Sea oil

North Sea oil is a mixture of hydrocarbons, comprising liquid petroleum and natural gas, produced from petroleum reservoirs beneath the North Sea.

In the petroleum industry, the term "North Sea" often includes areas such as the Norwegian ...

created a major new industry after 1970, and some older firms successfully took advantage of the opportunity. John Brown & Company

John Brown and Company of Clydebank was a Scottish Naval architecture, marine engineering and shipbuilding firm. It built many notable and world-famous ships including , , , , , and ''Queen Elizabeth 2 (ship), Queen Elizabeth 2''.

At its heig ...

's shipyard at Clydebank transformed itself from a traditional shipbuilding business to a factor in the high technology offshore oil and gas drilling industry.

Popular response varied. According to economic sociologist Jacqueline O'Reilly, the political reverberations of deindustrialisation contributed towards a rise in support for UKIP

The UK Independence Party (UKIP, ) is a Eurosceptic, right-wing populist political party in the United Kingdom. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), member ...

among voters in former industrial areas, and eventually came to a head in the vote in favour of the UK leaving the EU at the EU referendum on 23 June 2016. Historian Tom Devine

Sir Thomas Martin Devine (born 30 July 1945), usually known as Sir Tom Devine, is a Scottish academic and author who specializes in the history of Scotland. He was knighted and made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for his contr ...

has argued that the experience of deindustrialisation had a particular impact on trust in the Conservative party among residents of Scotland and pushed political attitudes in a more left-wing, economically interventionist

A market intervention is a policy or measure that modifies or interferes with a market, typically done in the form of state action, but also by philanthropic and political-action groups. Market interventions can be done for a number of reason ...

direction contributing to support for Scottish Independence in the 21st Century.

Economic policies and patterns in the 1980s and 1990s

Thatcher's deregulation of the economy ended the post-war consensus about the planned economy. She was elected during a period of crises between the Labour Party and the trade unions, and an increasing trend of higher unemployment and deindustrialisation. She liberalised the City of London and privatised state-owned enterprises. Inflation fell and trade union influence was significantly reduced. The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) had for a long time, been one of the strongest trade unions. Its strikes had toppled the Heath ministry at the February 1974 general election. Thatcher drew the line and defeated it at the bitterly fought miners' strike of 1984–1985. The basic problem was that the easy coal had all been mined and what was left was expensive and uneconomical. The miners were fighting not just for higher wages, but for a way of life that, to continue, had to be subsidised by other workers. The Union split. In the end, almost all the coal mines were shut down. Britain turned to its vast reserves ofNorth Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

gas and oil, which brought in substantial tax and export revenues, to fuel a new economic boom.

Following the economic boom of the 1980s, a brief but severe recession occurred between 1990 and 1992, mostly under the ministry of John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

; who succeeded Thatcher as prime minister and Conservative Party leader in November 1990. The pound was ejected from the Exchange Rate Mechanism

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro (replacing ERM 1 and the euro's predecessor, the ECU) as ...

on Black Wednesday

Black Wednesday, or the 1992 sterling crisis, was a financial crisis that occurred on 16 September 1992 when the UK Government was forced to withdraw sterling from the (first) European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERMI), following a failed at ...

in September 1992, an event which was humiliating for the Conservative government but which helped boost the recovery.

The rest of the 1990s saw a period of continuous economic growth that lasted over sixteen years and was greatly expanded under Blair's New Labour

New Labour is the political philosophy that dominated the history of the British Labour Party from the mid-late 1990s to 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The term originated in a conference slogan first used by the ...

government following his landslide election victory at 1997 general election, with a rejuvenated Labour Party abandoning its commitment to old policies like nuclear disarmament and nationalisation of key industries, and no reversal of the Thatcher-led union reforms. Many traditional Labour supporters were unhappy with Blair abandoning socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and the restructuring of Clause IV in 1995; effectively tearing up the constitution which had put socialist values and common ownership of industry at the heart of party policy for nearly eighty years. Blair promoted the Labour Party as "New Labour

New Labour is the political philosophy that dominated the history of the British Labour Party from the mid-late 1990s to 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The term originated in a conference slogan first used by the ...

", a social democratic centrist party for the 21st century which promised to inject new life into Britain; with investment in education made a key priority.

Since 1997

Tony Blair and New Labour

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

became the Leader of the Labour Party in 1994, and served as prime minister from 1997 to 2007. With Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. Previously, he was Chancellor of the Ex ...

, he founded the movement known as New Labour. In domestic policy, Blair sought to modernise Britain's public services, encourage enterprise and innovation in its private sector and keep the economy open to international commerce. The Northern Irish, Scottish and Welsh devolutions took place under his premiership.

Kavanagh argues that by the 1980s, left-wing or socialist tendencies in the Labour Party divided the party and united its enemies:

Blair moved the Labour Party in new directions, minimising the left-wing or socialist factions. He thereby broadened the appeal to professionals and middle-class voters in "Middle England

The phrase "Middle England" is a socio-political term which generally refers to middle class or lower middle class people in England who hold traditional conservative or right-wing views.

Origins

The origins of the term "Middle England" are n ...

", who had traditionally voted Conservative.

Blair was also anxious to escape from the Labour Party's reputation for "tax-and-spend" domestic policies; he wanted instead to establish a reputation for fiscal prudence. He had undertaken in general terms measures to modernise the welfare state, but he had avoided undertaking measures to reduce poverty, achieve full employment, or reverse the increase in inequality that had occurred during the Thatcher years. Once in office, however, his government launched a package of social policies designed to reduce unemployment and poverty. The commitment to modernise the welfare state was tackled by the introduction of "welfare to work" programmes to motivate the unemployed to return to work instead of drawing benefit. Poverty reduction programmes were targeted at specific groups, including children and the elderly, and took the form of what were termed "New Deals".

There were also new Tax Credit allowances for low-income and single-parent families with children, and "Sure Start" programmes for under-fours in deprived areas. A "National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal" was launched in 2001 with the objective of ensuring that "within 10 to 20 years no-one should be seriously disadvantaged by where they live"; a "Social Exclusion Unit" was set up, and annual progress reports concerning the reduction of poverty and social exclusion were commissioned.

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. Previously, he was Chancellor of the Ex ...

replaced Blair as Prime Minister in 2007. Labour's popularity declined further with the onset of a worldwide recession in 2008, where the Conservatives led by David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

overtook Labour in the polls for the first time in many years. In Scotland, the SNP and Lib Dems

The Liberal Democrats, colloquially known as the Lib Dems, are a Liberalism, liberal political party in the United Kingdom, founded in 1988. They are based at Liberal Democrat Headquarters (UK), Liberal Democrat Headquarters, in Westminster, ...

managed to win seats from Labour at by-elections in a further blow to the government. Arguably, the controversial decision for the UK to support the invasion of Iraq in 2003 sparked the beginning of Labour's decline in popularity; as their majority was significantly reduced at the 2005 general election. Five years later, Labour lost 91 seats in the House of Commons at the 2010 general election, the party's biggest loss of seats at a single general election since 1931

Events

January

* January 2 – South Dakota native Ernest Lawrence invents the cyclotron, used to accelerate particles to study nuclear physics.

* January 4 – German pilot Elly Beinhorn begins her flight to Africa.

* January 22 – Sir I ...

. On 11 May 2010, Brown was succeeded as prime minister by David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

of the Conservative Party, and resigned as Leader of the Labour Party on the same day after nearly three years. The 2010 election was seen as marking the end of the "New Labour" era both in the country at large and the Labour Party with all candidates in the subsequent leadership election keen to separate themselves from the movement. Ed Miliband

Edward Samuel Miliband (born 24 December 1969) is a British politician who has served as Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero since July 2024. He has been Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for D ...

was elected as the new Labour leader on 25 September.

Conservatives return

The economic damage done by theGreat Recession

The Great Recession was a period of market decline in economies around the world that occurred from late 2007 to mid-2009.

weakened Labour's image and facilitated a Conservative comeback after thirteen years in opposition. Since his election as Conservative Party leader in 2005, David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

sought to rebrand the Conservatives, embracing an increasingly socially liberal position; as opposed to the socially conservative values the party traditionally advocated. The 2010 general election resulted in a hung parliament, the first in 36 years; and led to Cameron becoming prime minister as the head of a coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

with the centrist Liberal Democrats. His premiership was marked by the ongoing negative economic effects of the late 2000s worldwide financial crisis. He faced a large deficit in government finances that he sought to reduce through austerity measures. His government introduced large-scale changes to welfare

Welfare may refer to:

Philosophy

*Well-being (happiness, prosperity, or flourishing) of a person or group

* Utility in utilitarianism

* Value in value theory

Economics

* Utility, a general term for individual well-being in economics and decision ...

, immigration policy

Immigration law includes the national statutes, regulations, and legal precedents governing immigration into and deportation from a country. Strictly speaking, it is distinct from other matters such as naturalization and citizenship, although the ...

, education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

, and healthcare

Health care, or healthcare, is the improvement or maintenance of health via the preventive healthcare, prevention, diagnosis, therapy, treatment, wikt:amelioration, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other disability, physic ...

.

Cameron's government privatised the Royal Mail

Royal Mail Group Limited, trading as Royal Mail, is a British postal service and courier company. It is owned by International Distribution Services. It operates the brands Royal Mail (letters and parcels) and Parcelforce Worldwide (parcels) ...

and some other state assets, and legalised same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same legal Legal sex and gender, sex. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 38 countries, with a total population of 1.5 ...

in July 2013. He was re-elected in 2015, with 330 seats in the House of Commons; enabling him to form a majority government. This result was unexpected, as another hung parliament was predicted by most major polls. Cameron formed the first Conservative majority government since 1992

1992 was designated as International Space Year by the United Nations.

Events January

* January 1 – Boutros Boutros-Ghali of Egypt replaces Javier Pérez de Cuéllar of Peru as United Nations Secretary-General.

* January 6

** The Republ ...

, while Labour lost nearly all its Scottish seats to the SNP in the aftermath of the Scottish independence referendum

A referendum on Scottish independence from the United Kingdom was held in Scotland on 18 September 2014. The referendum question was "Should Scotland be an independent country?", which voters answered with "Yes" or "No". The "No" side won ...

and Miliband resigned as party leader. This unexpected result gave the governing Conservatives a mandate to renegotiate the terms of the UK's membership of the European Union during the autumn and winter of 2015–16 which was concluded in February 2016 and was then followed by a national referendum on the United Kingdom's continued membership to the European Union itself which was held on 23 June 2016.

On the morning of Friday 24 June 2016, when the results of the EU referendum were announced, Cameron announced his intention to step down as prime minister and Leader of Conservative Party at the Conservative Party conference in the autumn of that year following the British electorate's vote to Leave the European Union in a nationwide referendum; his government having campaigned for a "Remain" vote. He resigned earlier than intended on 13 July 2016, and was succeeded by former Home Secretary Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Baroness May of Maidenhead (; ; born 1 October 1956), is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served as Home Secretar ...

, who called another general election for 8 June 2017, resulting in a hung parliament. The Labour Party, now under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who has been Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for Islington North (UK Parliament constituency), Islington North since 1983. Now an Independent ...

, made a net gain of seats for the first time in 20 years, and 30 new seats were gained by Labour overall; 6 of which were in Scotland. Notably, Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

and Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

had never returned Labour MPs to Parliament before, but both were narrowly gained at the expense of the Conservative Party. There was a 9.6% swing from Conservative to Labour, which was the largest swing from one party to another since 1945

1945 marked the end of World War II, the fall of Nazi Germany, and the Empire of Japan. It is also the year concentration camps were liberated and the only year in which atomic weapons have been used in combat.

Events

World War II will be ...

.

The Liberal Democrat

Several political parties from around the world have been called the Liberal Democratic Party, Democratic Liberal Party or Liberal Democrats. These parties have usually followed liberalism as ideology, although they can vary widely from very progr ...

's former party leader and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg

Sir Nicholas William Peter Clegg (born 7 January 1967) is a British retired politician and media executive who served as Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2015 and as Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 2007 to 2015. H ...

lost his Sheffield Hallam seat to Labour, and former Secretary of State for Business Sir Vince Cable

Sir John Vincent Cable (born 9 May 1943) is a British politician who was Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 2017 to 2019. He was Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for Twickenham (UK Parliament constituency), Twic ...

regained the Twickenham seat from the Conservatives two years previously. Cable succeeded Tim Farron

Timothy James Farron (born 27 May 1970) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 2015 to 2017. He has been the Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for Westmorland and Lonsdale since ...

as Lib Dem leader after the election, and three new seats were gained for the party in Scotland. UKIP led by Paul Nuttall

Paul Andrew Nuttall (born 30 November 1976) is a British politician who served as Leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) from 2016 to 2017. He was elected to the European Parliament in 2009 as a UK Independence Party (UKIP) candidate, and ...

made no gains and lost the majority of its previous supporters to the Labour and Conservative parties; signifying an end to multi-party politics and a return to two-party politics. Nuttall stood at Boston and Skegness

Boston and Skegness is a Constituencies of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, constituency in Lincolnshire represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the UK Parliament by Richard Tice of Reform UK since the ...

, which was the constituency with the highest vote to leave the EU at the referendum. However, Nuttall finished in third place and resigned as UKIP leader. The Conservatives remained in power and Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Baroness May of Maidenhead (; ; born 1 October 1956), is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served as Home Secretar ...

remained as prime minister through a confidence and supply agreement made with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist, Ulster loyalism, loyalist, British nationalist and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who ...

.

The next couple of years were defined by political instability as the government attempted to conduct the process of withdrawing the United Kingdom from the EU in the context of a hung parliament. Both Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Baroness May of Maidenhead (; ; born 1 October 1956), is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served as Home Secretar ...

and her successor Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

failed to reach a consensus in Parliament for leaving the EU in a way they wished, eventually resulting in another general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

in late 2019. At this election, the Conservatives made a net gain of 48 seats and were returned with the largest majority for a governing party since 2001

The year's most prominent event was the September 11 attacks against the United States by al-Qaeda, which Casualties of the September 11 attacks, killed 2,977 people and instigated the global war on terror. The United States led a Participan ...

in what was regarded as a landslide victory, winning 43.6% of the vote (the highest share for any party since 1979

Events

January

* January 1

** United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim heralds the start of the ''International Year of the Child''. Many musicians donate to the ''Music for UNICEF Concert'' fund, among them ABBA, who write the song ...

) and 365 seats (the highest number for the party since 1987

Events January

* January 1 – Bolivia reintroduces the Boliviano currency.

* January 2 – Chadian–Libyan conflict – Battle of Fada: The Military of Chad, Chadian army destroys a Libyan armoured brigade.

* January 3 – Afghan leader ...

). Labour made a net loss of 60 seats, losing several of its constituencies in northern England, across the Midlands and Wales to the Conservatives in what was widely referred to as a collapse of the Red Wall. The SNP made a net gain of 13 seats across Scotland, winning 45% of the Scottish vote and 48 of the 59 Scottish seats. In Northern Ireland, more Irish Nationalist MPs were elected than British Unionists for the first time, although unionist parties still won more votes. After the Conservative victory, Parliament ratified the EU withdrawal agreement that Johnson had negotiated and the UK left the EU at the end of January the following year.

Early in 2020, the coronavirus pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

spread to the United Kingdom. The attempt to combat the disease led to disruptions in everyday life on a scale not seen since World War II, including closures of schools and other educational institutions, shops selling non-essential goods and most public facilities for eating, entertainment and leisure, as well as cancellations of events and restrictions on people's rights to gather in public places and leave their homes.

Economic growth and crises since 1995

Housing

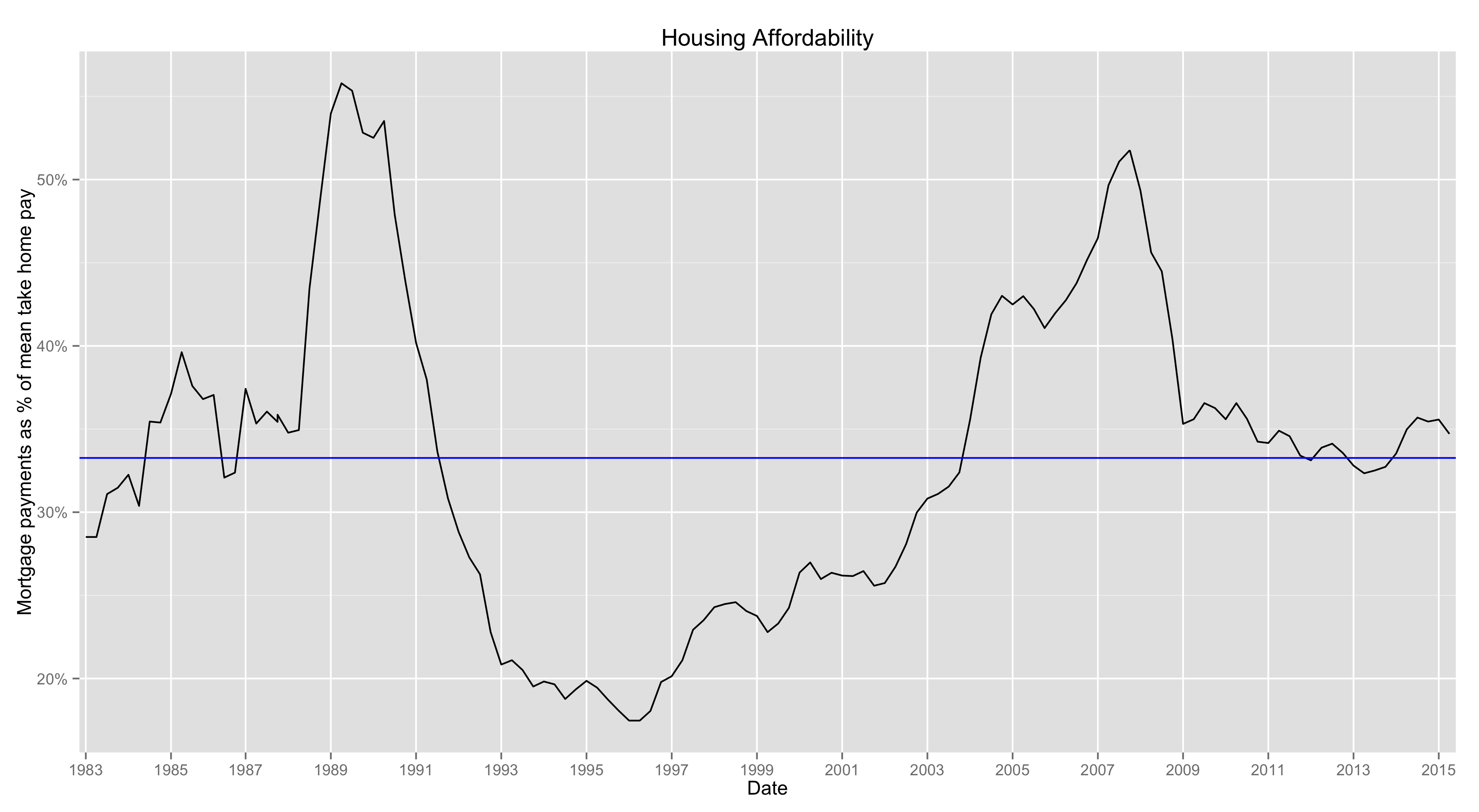

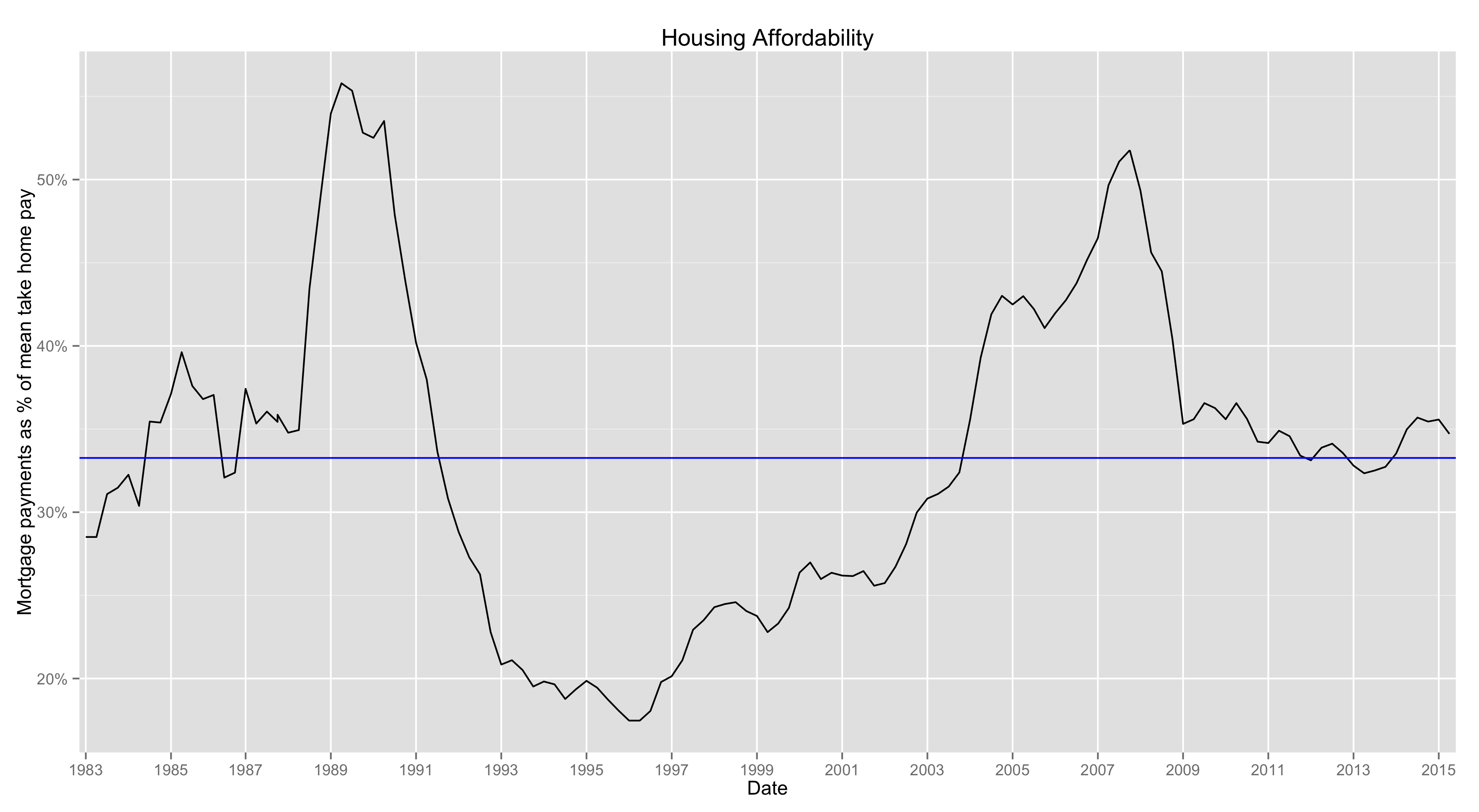

House prices tripled in the 20 years between 1995 and 2015. Growth was almost continuous during the period, save for a two-year period of decline around 2008 as a result of the

House prices tripled in the 20 years between 1995 and 2015. Growth was almost continuous during the period, save for a two-year period of decline around 2008 as a result of the banking crisis

A bank run or run on the bank occurs when many clients withdraw their money from a bank, because they believe the bank may fail in the near future. In other words, it is when, in a fractional-reserve banking system (where banks normally only ...

. The gap between income and house prices has changed in the last 20 years such that even in the most affordable regions of England and Wales buyers have to spend six times their income. It was most marked in London, where in 2013 the £300,000 median

The median of a set of numbers is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a Sample (statistics), data sample, a statistical population, population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as the “ ...

house price cost 12 times the median London income of £24,600.

Brexit

Economic and social issues caused political unrest, particularly in areas hurt by deindustrialization and globalization of the economy. TheUK Independence Party

The UK Independence Party (UKIP, ) is a Eurosceptic, right-wing populist political party in the United Kingdom. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two members of parliament (both through defect ...

(UKIP), a Eurosceptic

Euroscepticism, also spelled as Euroskepticism or EU-scepticism, is a political position involving criticism of the European Union (EU) and European integration. It ranges from those who oppose some EU institutions and policies and seek refor ...

political party, was founded in 1993. It rose to prominence after 2000, winning third place in the 2004 European elections, second place in the 2009 European elections

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Hindu–Arabic digit

Circa 300 BC, as part of the Brahmi numerals, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bot ...

and first place in the 2014 European elections, with 27.5% of the total vote. Cameron won reelection in 2015 in part by promising a referendum on the EU, which he expected would defeat Brexit

Brexit (, a portmanteau of "Britain" and "Exit") was the Withdrawal from the European Union, withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU).

Brexit officially took place at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February ...

.

The 'Leave' pro-Brexit campaign focused strongly on sovereignty and the need to control migration, whereas the 'Remain' campaign focused on the negative economic impacts of leaving the EU. Polls showed more cited both the EU (32%) and migration (48%) as important issues than cited the economy (27%). By 2018 as the complexities of leaving the EU dominated political discussions, economists produced gloomy projections of the damage to the British economy.

Social and cultural forces

Diana, Princess of Wales

During the summer of 1981, the nation's spirits were raised by thewedding

A wedding is a ceremony in which two people are united in marriage. Wedding traditions and customs vary greatly between cultures, ethnicity, ethnicities, Race (human categorization), races, religions, Religious denomination, denominations, Cou ...

of Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

and Lady Diana Spencer

Diana, Princess of Wales (born Diana Frances Spencer; 1 July 1961 – 31 August 1997), was a member of the British royal family. She was the first wife of Charles III (then Prince of Wales) and mother of Princes William ...

. The ceremony reached a global TV audience of 750 million people. It restored the royal family to the headlines where they would become a permanent fixture in tabloids and celebrity gossip publications, as well as a major tourist attraction. Diana became what Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

later called the "People's Princess", an iconic national figure, rivalling or surpassing the Queen, until her divorce. Her accidental death brought an unprecedented spasm of grief and mourning. Her brother, the 9th Earl Spencer, captured her role:Diana was the very essence of compassion, of duty, of style, of beauty. All over the world she was a symbol of selfless humanity. All over the world, a standard bearer for the rights of the truly downtrodden, a very British girl who transcended nationality. Someone with a natural nobility who was classless and who proved in the last year that she needed no royal title to continue to generate her particular brand of magic.

Religion

Secularisation