Sir Wilfrid Lawson, 2nd Baronet, Of Brayton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Wilfrid Lawson, 2nd Baronet (4 September 18291 July 1906) was an English temperance campaigner and

/ref> He was always an enthusiast in the cause of temperance and in 1879 he became president of the

On 13 November 1860, Lawson married Mary, daughter of Joseph Pocklington Senhouse of Netherhall,

On 13 November 1860, Lawson married Mary, daughter of Joseph Pocklington Senhouse of Netherhall,

The Lawsons shared the opinions of

The Lawsons shared the opinions of

Lawson was a member of innumerable societies and

Lawson was a member of innumerable societies and

After

After

Under normal circumstances Lawson should have returned to the House of Commons in 1865; however, during the previous year he had introduced the Permissive Bill. A Bill so unpopular, he struggled to find a member to

Under normal circumstances Lawson should have returned to the House of Commons in 1865; however, during the previous year he had introduced the Permissive Bill. A Bill so unpopular, he struggled to find a member to

As the 1874

As the 1874

On 30 June, though feeling tired and weary, Lawson went down to the House to record his vote. From where he returned to No 18, Ovington Square,

On 30 June, though feeling tired and weary, Lawson went down to the House to record his vote. From where he returned to No 18, Ovington Square,  The interment of the remains took place at

The interment of the remains took place at

On 6 June 1908, the Lawson family installed a stained glass window dedicated to the memory of their late patriarch, in the east end of Aspatria Church. The window is large and beautifully ornate, and symbolises the characters and scene of the last chapter of Revelations.

On 20 July 1909, the members of the

On 6 June 1908, the Lawson family installed a stained glass window dedicated to the memory of their late patriarch, in the east end of Aspatria Church. The window is large and beautifully ornate, and symbolises the characters and scene of the last chapter of Revelations.

On 20 July 1909, the members of the

radical

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

, anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influenc ...

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

politician who sat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

variously between 1859 and 1906. He was recognised as the leading humourist in the House of Commons.

Lawson was Member for Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from ) is a city in the Cumberland district of Cumbria, England.

Carlisle's early history is marked by the establishment of a settlement called Luguvalium to serve forts along Hadrian's Wall in Roman Britain. Due to its pro ...

, 1859–65, 1868–85; Cockermouth

Cockermouth is a market town and civil parish in the Cumberland unitary authority area of Cumbria, England. The name refers to the town's position by the confluence of the River Cocker into the River Derwent. At the 2021 census, the built u ...

, 1886–1900; Camborne

Camborne (from Cornish language, Cornish ''Cambron'', "crooked hill") is a town in Cornwall, England. The population at the 2011 Census was 20,845. The northern edge of the parish includes a section of the South West Coast Path, Hell's Mouth, C ...

, 1903–1906; and Cockermouth 1906. He was the son of Sir Wilfrid Lawson, 1st Baronet, of Brayton

Sir Wilfrid Lawson, 1st Baronet, of Brayton (5 October 1795 – 12 June 1867), was an English landowner, businessman and investor in the new industrial age. He was of the Lawson baronets.

Early life

After the death of Sir Wilfrid Lawson, 10t ...

, who changed his name from Wybergh, and Caroline Graham, daughter of Sir James Graham. He was privately educated at home. He was a founder member of both the National Liberal Club

The National Liberal Club (NLC) is a London private members' club, open to both men and women. It was established by William Ewart Gladstone in 1882 to provide club facilities for Liberal Party campaigners among the newly enlarged electorate f ...

and the Reform League

The Reform League was established in 1865 to press for manhood suffrage and the ballot in Great Britain. It collaborated with the more moderate and middle class Reform Union and gave strong support to the abortive Reform Bill 1866 and the su ...

, a prominent member of the Peace Society

The Peace Society, International Peace Society or London Peace Society, originally known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was a British pacifist organisation that was active from 1816 until the 1930s.

History Fo ...

, and the Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade. He was a director of the Maryport and Carlisle Railway

The Maryport & Carlisle Railway (M&CR) was an English railway company formed in 1836 which built and operated a small but eventually highly profitable railway to connect Maryport and Carlisle, Cumberland, Carlisle in Cumberland, England. There ...

and a Justice of the Peace for Cumberland.Debretts House of Commons and the Judicial Bench 1881/ref> He was always an enthusiast in the cause of temperance and in 1879 he became president of the

United Kingdom Alliance

The United Kingdom Alliance (UKA) was a British temperance organisation. It was founded in 1853 in Manchester to work for the prohibition of the trade in alcohol in the United Kingdom. This occurred in a context of support for the type of law p ...

. He was, like his younger brother William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

, a forward-thinking co-operator and agriculturalist.

Early days

Wilfrid Lawson the son ofSir Wilfrid Lawson, 1st Baronet, of Brayton

Sir Wilfrid Lawson, 1st Baronet, of Brayton (5 October 1795 – 12 June 1867), was an English landowner, businessman and investor in the new industrial age. He was of the Lawson baronets.

Early life

After the death of Sir Wilfrid Lawson, 10t ...

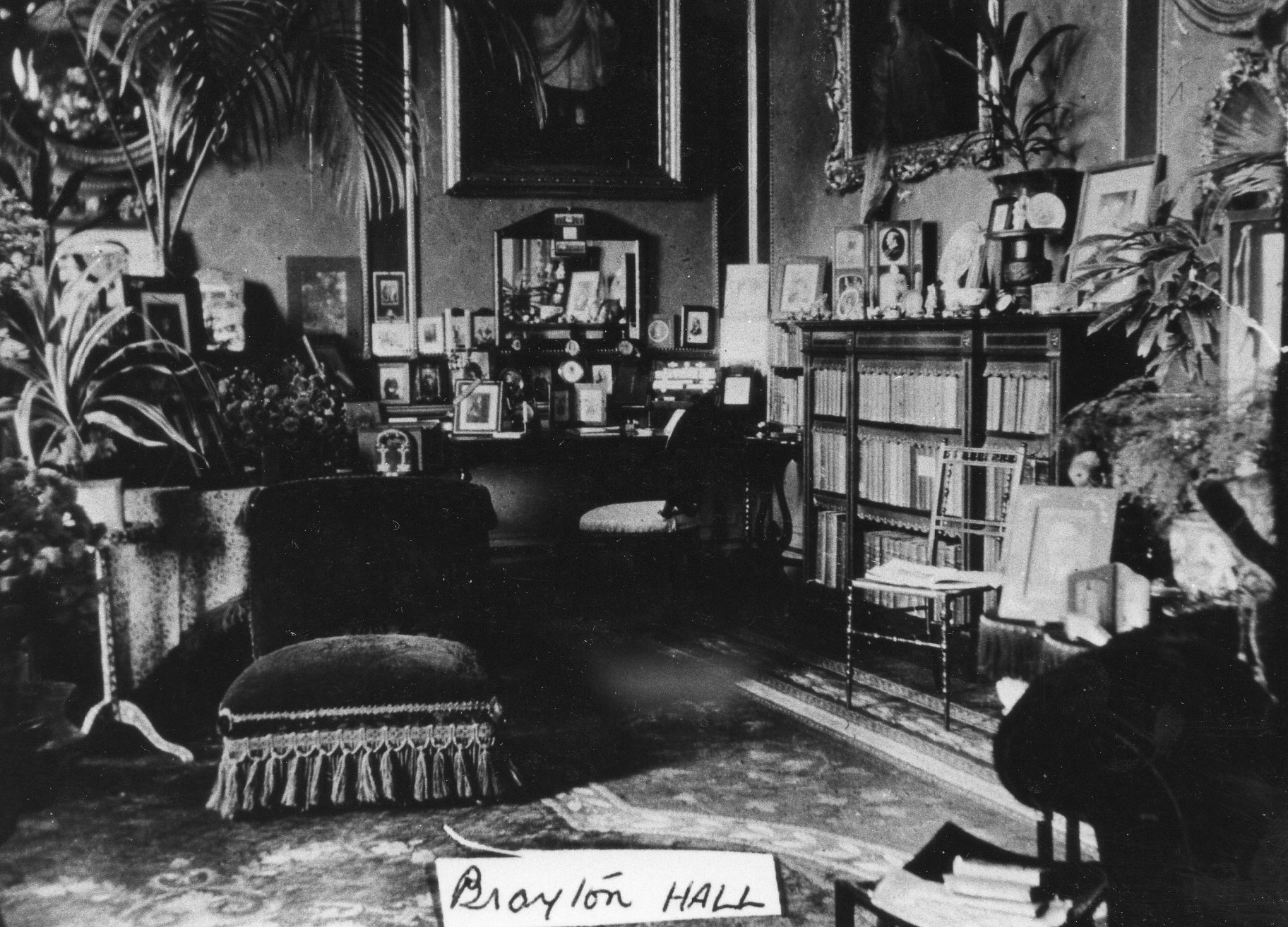

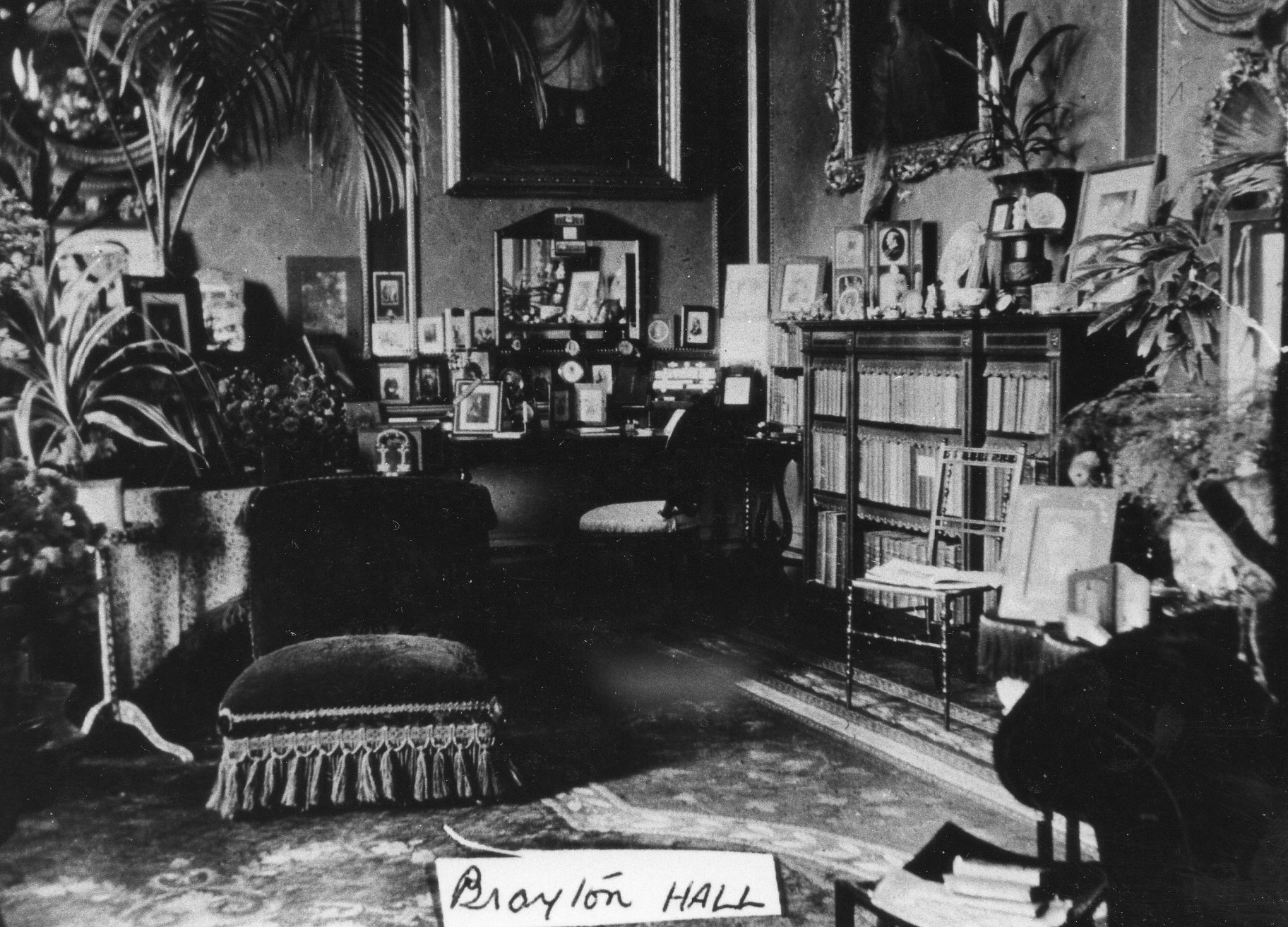

, was born at Brayton Hall, Aspatria

Aspatria is a town and civil parish in Cumberland, Cumbria, England. The town rests on the north side of the Ellen Valley, overlooking a panoramic view of the countryside, with Skiddaw to the South and the Solway Firth to the North. Its dev ...

, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is an area of North West England which was historically a county. The county was bordered by Northumberland to the north-east, County Durham to the east, Westmorland to the south-east, Lancashire to the south, and the Scottish ...

on 4 September 1829. Since the family preferred a simple sporting life, they encouraged their children to enjoy a string of outdoor pursuits, including fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment (Freshwater ecosystem, freshwater or Marine ecosystem, marine), but may also be caught from Fish stocking, stocked Body of water, ...

, shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missile ...

, ice skating

Ice skating is the Human-powered transport, self-propulsion and gliding of a person across an ice surface, using metal-bladed ice skates. People skate for various reasons, including recreation (fun), exercise, competitive sports, and commuting. ...

, cricket

Cricket is a Bat-and-ball games, bat-and-ball game played between two Sports team, teams of eleven players on a cricket field, field, at the centre of which is a cricket pitch, pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two Bail (cr ...

and the family obsession, foxhunting

Fox hunting is an activity involving the tracking, chase and, if caught, the killing of a fox, normally a red fox, by trained foxhounds or other scent hounds. A group of unarmed followers, led by a "master of foxhounds" (or "master of houn ...

. He bought John Peel's pack of hounds after Peel's death and became Master of the Cumberland Foxhounds. From early childhood, he developed an exceptional talent for mimicry and a talent for writing rapid, fluent, and vigorous verse that played so conspicuous a part in the serious correspondence of his mature life.

He received his education at home under the tutorship of John Oswald Jackson, a Congregational

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christianity, Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice Congregationalist polity, congregational ...

minister of some repute. In later life, both Lawson and his celebrated brother William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

openly declared their lack of formal education. Jackson predominantly taught his pupils Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

, complemented with mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

s, political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

and foreign history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

, with the elements of rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

and logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

to enhance the curriculum. Lawson also gained a fondness for poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

, in particular the works of Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

, whose lines often adorned his political speeches.

Family

On 13 November 1860, Lawson married Mary, daughter of Joseph Pocklington Senhouse of Netherhall,

On 13 November 1860, Lawson married Mary, daughter of Joseph Pocklington Senhouse of Netherhall, Maryport

Maryport is a town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Cumberland (unitary authority), Cumberland district of Cumbria, England. The town is on the coast of the Solway Firth and lies at the northern end of the former Cumberland Co ...

, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is an area of North West England which was historically a county. The county was bordered by Northumberland to the north-east, County Durham to the east, Westmorland to the south-east, Lancashire to the south, and the Scottish ...

. Their union produced eight children; four boys, Wilfrid, Mordaunt, Arthur and Godfrey; and four girls. Ellen, Mabel, Lucy and Josephine. Ellen married Arthur Henry Holland-Hibbert, 3rd Viscount Knutsford

Arthur is a masculine given name of uncertain etymology. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur.

A common spelling variant used in many Slavic, Romance, and Germanic languages is Artur. In Spanish and Ital ...

(1855–1935), they produced one daughter named Elsie and one son named Thurstan. In 1895, Mabel married Alan de Lancey Curwen of Workington Hall

Workington Hall, sometimes called Curwen Hall, is a ruined building on the Northeast outskirts of the town of Workington in Cumbria. It is a Grade I listed building.

History

A peel tower was built on the site in 1362. The present house dates b ...

, and they had three children. In 1896, Lucy married Edward Heathcote Thruston of Pennal

Pennal is a village and community on the A493 road in southern Gwynedd, Wales, on the north bank of the River Dyfi, near Machynlleth.

It lies in the historic county of Merionethshire () and is within the Snowdonia National Park.

Roman for ...

Tower, Mochgullith, North Wales

North Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, with Snowdon ...

In 1909, Josephine married Frederick William Chance, the member of Parliament for the city of Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from ) is a city in the Cumberland district of Cumbria, England.

Carlisle's early history is marked by the establishment of a settlement called Luguvalium to serve forts along Hadrian's Wall in Roman Britain. Due to its pro ...

. Mary's sister, Blanche, married Alfred Curzon, 4th Baron Scarsdale (1831–1916). Blanche was the mother of Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

, Viceroy of India

The governor-general of India (1833 to 1950, from 1858 to 1947 the viceroy and governor-general of India, commonly shortened to viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom in their capacity as the Emperor of ...

. Lawson succeeded to the baronetcy and estates upon the death of his father in 1867.

Early political influences

With limited access to his intellectual peers, Lawson received his political convictions from his father and a constant stream of influential household guests. In 1840, the family explored the consequences of adoptingfree trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

and the repeal of the iniquitous Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

. They eagerly digested the speeches of Granby, Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creat ...

, and the Duke of Richmond

Duke of Richmond is a title in the Peerage of England that has been created four times in British history. It has been held by members of the royal Tudor and Stuart families.

The current dukedom of Richmond was created in 1675 for Charles ...

on one side and of Cobden, Bright

Bright may refer to:

Common meanings

*Bright, an adjective meaning giving off or reflecting illumination; see Brightness

*Bright, an adjective meaning someone with intelligence

People

* Bright (surname)

* Bright (given name)

*Bright, the stage na ...

and Villiers on the other, with the caricatured comments of Mr. Punch, to enrich the subject.

The Lawsons shared the opinions of

The Lawsons shared the opinions of radicals

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

, who argued that aristocrats

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense economic, political, and social influence. In Western Christian co ...

were parasites of the state raising the price of the people's bread as a means of helping the landed interests and to add revenue to the state coffers which could be used for the anti-Christian purposes of corruption and foreign war. In 1843, after attending a series of travelling lectures given by Chalmers and Candlish Candlish is a Scottish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* James Smith Candlish (1835–1892), Scottish minister, son of Robert

* John Candlish (1816–1874), British glass bottle manufacturer and Liberal Party politician

* Louis ...

, they re-enacted the prominent debates relating to the question of Church and State

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

and discussed the Scottish church and its recent schism, when 451 ministers seceded, leaving the Kirk

Kirk is a Scottish and former Northern English word meaning 'church'. The term ''the Kirk'' is often used informally to refer specifically to the Church of Scotland, the Scottish national church that developed from the 16th-century Reformation ...

to form the Free Church of Scotland In contemporary usage, the Free Church of Scotland usually refers to:

* Free Church of Scotland (since 1900), that portion of the original Free Church which remained outside the 1900 merger; extant

It may also refer to:

* Free Church of Scotland (1 ...

. In 1843, they debated the Rebecca Riots

The Rebecca Riots () took place between 1839 and 1843 in West and Mid Wales. They were a series of protests undertaken by local farmers and agricultural workers in response to levels of taxation. The rioters, often men dressed as women, took ...

; and after Daniel O'Connell

Daniel(I) O’Connell (; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilisation of Catholic Irelan ...

electrified Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

with his desire to repeal the union they consumed endless hours debating the everlasting Irish Question. In 1848, they contemplated the events surrounding the revolution, when the morning newspapers reported some fresh upheaval, spreading relentlessly across Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, shaking kingdoms

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchic state or realm ruled by a king or queen.

** A monarchic chiefdom, represented or governed by a king or queen.

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and me ...

and thrones, causing terrific slaughter in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, provoking Chartist riots in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, and bringing home lessons of deep political importance. Throughout the 1840s, they debated the morality of war, with particular reference to the Afghan

Afghan or Afgan may refer to:

Related to Afghanistan

*Afghans, historically refers to the Pashtun people. It is both an ethnicity and nationality. Ethnicity wise, it refers to the Pashtuns. In modern terms, it means both the citizens of Afghanist ...

and the Chinese Opium Wars. As the wars concluded the question of peace came to the fore. The leaflets of Elihu Burritt

Elihu Burritt (December 8, 1810March 6, 1879) was an American diplomat, philanthropist, social activist, and blacksmith.Arthur Weinberg and Lila Shaffer Weinberg. ''Instead of Violence: Writings by the Great Advocates of Peace and Nonviolence Thr ...

' a leading peace campaigner were awaited and absorbed on publication, while another apostle of peace, Henry Richard

Henry Richard (3 April 1812 – 20 August 1888) was a Congregational minister and Wales, Welsh Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament between 1868–1888. Richard was an advocate of peace and international arbitration, ...

made a lecturing visit to Brayton. Lawson completed his education by reading The Nonconformist, edited by Edward Miall

Edward Miall (8 May 1809 – 30 April 1881) was an English journalist, apostle of Disestablishmentarianism, disestablishment, founder of the Liberation Society (Society for the Liberation of the Church from State Patronage and Control), and Libe ...

. Many of these early Whig refrains forged his character and formed his opinions and convictions pushing him along a path that led from romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

and Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

to Cobdenism

Cobdenism is an economic ideology (and the associated popular movement) which perceives international free trade and a non-interventionist foreign policy as the key requirements for prosperity and world peace. It is named after the British states ...

.

Political style

In his lifetime Lawson was one of Britain's most celebrated and popular political figures and yet he was not apamphleteer

A pamphleteer is a historical term used to describe someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (therefore inexpensive) booklets intended for wide circulation.

Context

Pamphlets were used to broadcast the writer's opinions: to articu ...

or an essayist, nor was he the owner of a newspaper or a periodical

Periodical literature (singularly called a periodical publication or simply a periodical) consists of Publication, published works that appear in new releases on a regular schedule (''issues'' or ''numbers'', often numerically divided into annu ...

like his radical colleagues, Joseph Cowen

Joseph Cowen, Jr., (9 July 1829 – 18 February 1900) was an English radical Liberal politician and journalist. He was a firm friend to Anglo-Jewry, and an early advocate of Jewish emancipation in the United Kingdom, Jewish emancipation, r ...

and Henry Labouchere

Henry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Henry (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters

* Henry (surname)

* Henry, a stage name of François-Louis Henry (1786–1855), French baritone

Arts and entertainment ...

. His strength of argument came from his unique way of transmitting the spoken word, which seldom lacked qualities of humour or entertainment such that his precise, logical, well-balanced arguments ranked high, when compared to contemporary political orators. Lawson became the chief jester

A jester, also known as joker, court jester, or fool, was a member of the household of a nobleman or a monarch kept to entertain guests at the royal court. Jesters were also travelling performers who entertained common folk at fairs and town ma ...

to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

, where he contributed a rich, racy style to debates, earning him the epithet the "witty baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

".

Lawson was a member of innumerable societies and

Lawson was a member of innumerable societies and pressure groups

Advocacy groups, also known as lobby groups, interest groups, special interest groups, pressure groups, or public associations, use various forms of advocacy or lobbying to influence public opinion and ultimately public policy. They play an impor ...

, and made many political speeches throughout his life on a wide variety of subjects and related incidents. Today he is widely remembered for his pursuit of the lost cause of temperance reform, when temperance was only one strand of a very complex set of ideas he espoused. Lawson was in fact, the most Cobdenite

Cobdenism is an economic ideology (and the associated popular movement) which perceives international free trade and a non-interventionist foreign policy as the key requirements for prosperity and world peace. It is named after the British states ...

of the Cobdenites and his contribution to the debate on radical reform, and foreign and colonial policy was significant. In the context of his radical philosophy as a whole, Lawson was a full-blooded radical, whose views covered a wide range and were almost always, very extreme. If the voting habits of an individual Member of Parliament can be used to place that person along the radical spectrum then Lawson belongs on the outer fringes, for it is doubtful if any member of any British political party or of any time in the history of the modern British parliamentary system, has ever voted in as many minority divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

as Lawson.

Political career

Entry into politics

AfterLord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

dissolved Parliament in 1857, Lawson came forward as a radical to contest the West Cumberland stronghold owned

Ownership is the state or fact of legal possession and control over property, which may be any asset, tangible or intangible. Ownership can involve multiple rights, collectively referred to as ''title'', which may be separated and held by diffe ...

by the Lowther family

This article summarises the relationships between various members of the family of Lowther baronets.

*Sir Christopher Lowther

**Sir John Lowther, of Lowther (d. 1637)

***Sir John Lowther, 1st Baronet, of Lowther, Sir John Lowther, 1st Baronet (160 ...

. The Lawsons were obsessed with the concept of political freedom and since the constituency

An electoral (congressional, legislative, etc.) district, sometimes called a constituency, riding, or ward, is a geographical portion of a political unit, such as a country, state or province, city, or administrative region, created to provi ...

had for over twenty years been denied the opportunity to select their representative Lawson senior was determined, at personal expense to offer the electorate a choice.The Carlisle Patriot, 10 April 1857 Lawson stood as a Little Englander

The Little Englanders were a British political movement who opposed empire-building and advocated complete independence for Britain's existing colonies. The ideas of Little Englandism first began to gain popularity in the late 18th century after ...

, with a radical programme endorsing the Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

watchwords, Peace, Retrenchment

Retrenchment (, an old form of ''retranchement'', from ''retrancher'', to cut down, cut short) is an act of cutting down or reduction, particularly of public expenditure.

Political usage

The word is familiar in its most general sense from the mot ...

and Reform. Lawson identified with the Manchester School of politics and consistently advocated their principles, particularly in response to conflict undertaken to promote selfish British interests. Although Lawson, a disappointing third in the poll, lost the election, the Manchester School in the form of Bright

Bright may refer to:

Common meanings

*Bright, an adjective meaning giving off or reflecting illumination; see Brightness

*Bright, an adjective meaning someone with intelligence

People

* Bright (surname)

* Bright (given name)

*Bright, the stage na ...

, Cobden, Miall, Milner Gibson and Layard all lost their seats.

1859 Carlisle election

After

After Lord Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby (29 March 1799 – 23 October 1869), known as Lord Stanley from 1834 to 1851, was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served three times as Prime Minister of the United K ...

dissolved Parliament in 1859, Lawson was invited to stand with his uncle, Sir James Graham for the Carlisle constituency. Although Graham's address was moderate, he informed his agent, "Lawson and his father sincerely entertain extreme opinions, and may be considered partisans of Mr Bright. Lawson would go the whole length, would pledge himself to the ballot

A ballot is a device used to cast votes in an election and may be found as a piece of paper or a small ball used in voting. It was originally a small ball (see blackballing) used to record decisions made by voters in Italy around the 16th cent ...

, and would go ahead of me." Lawson concurred; "I may honestly confess I am rather more of a radical than he (Graham)." When questioned on the lengths he would go in lowering the franchise, he replied, "As far as any proposition is likely to be brought into Parliament, which has the least chance of success." When the poll closed Graham stood at its head with 538 votes, Lawson trailed by 22 votes, 40 votes ahead of his Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

rival. As a result, he became a Member of Parliament. Lawson made his maiden speech on 20 March 1860, in a debate relating to the introduction of the Secret Ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ...

.

1865 Carlisle election

Under normal circumstances Lawson should have returned to the House of Commons in 1865; however, during the previous year he had introduced the Permissive Bill. A Bill so unpopular, he struggled to find a member to

Under normal circumstances Lawson should have returned to the House of Commons in 1865; however, during the previous year he had introduced the Permissive Bill. A Bill so unpopular, he struggled to find a member to second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

the proposal. Needless to say Lawson lost the division by 294 votes to 37. For suggesting that people had the right to restrict the access of others to the liquor shops, the full weight of public opinion favouring the liberty of the subject, backed by the Tories and brewing industry, rained down upon him. Although Lawson was popular for other reasons, and lost the election by a mere seventeen votes, it prompted ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' newspaper to run an article suggesting that no future sensible constituency would ever return him to the house. However, an opportunity arose for an early return to parliament in July 1866, after Lord Naas, the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

member for the small ancient borough

An ancient borough was a historic unit of lower-tier local government in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the co ...

of Cockermouth

Cockermouth is a market town and civil parish in the Cumberland unitary authority area of Cumbria, England. The name refers to the town's position by the confluence of the River Cocker into the River Derwent. At the 2021 census, the built u ...

became Chief Secretary of Ireland. When the redistribution of parliamentary seats became an electoral issue Lawson informed his would-be supporters that if elected he would not hesitate to do everything in his power, to support some form of borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

disenfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also disenfranchisement (which has become more common since 1982) or voter disqualification, is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing someo ...

. However, when his defeat became a forlorn conclusion he retired from the contest.

1868 Carlisle election

By openly supporting Gladstone's desire to disestablish the Irish Church Lawson endured the wrath of theChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

in the form of the Dean of Carlisle

The Dean of Carlisle is based in Carlisle, United Kingdom, and is the head of the Chapter of Carlisle Cathedral in the Church of England's Diocese of Carlisle. There have been 41 previous incumbents. The current dean is Jonathan Brewster; he took ...

, who proclaimed Lawson the greatest radical in all of Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

.Carlisle Journal, 1 September 1868 To those who accused Lawson of "robbing a poor man of his beer". He retorted, "Far from the truth I am trying to rob the rich man of his prey, out of the plunder he makes, from the homes and happiness of the working men of this country." He also supported the need for a national education policy

Education policy consists of the principles and policy decisions that influence the field of education, as well as the collection of laws and rules that govern the operation of education systems. Education governance may be shared between the local ...

based upon a secular system with the capacity to accommodate the various religious interests. Nationally the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

produced a landslide Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

victory with a majority of over one hundred. Lawson returned to parliament at the head of the Carlisle poll.

1874 Carlisle election

As the 1874

As the 1874 general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

approached, Lawson had good cause to feel satisfied with the progressive reforms introduced by the outgoing Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

government.Carlisle Journal, 16 January 1874 They had gone some way to pacify Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

by disestablishing the Irish church and introducing the Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870

The Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870 (33 & 34 Vict. c. 46) was an Act of Parliament (UK), act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1870.

Background

Between the Acts of Union 1800 and the year 1870, Parliament had passed ma ...

. They had introduced an Education Bill, which Lawson welcomed with a few reservations. They had introduced the Local Government Board Act 1871

The Local Government Board (LGB) was a British Government supervisory body overseeing local administration in England and Wales from 1871 to 1919.

The LGB was created by the Local Government Board Act 1871 ( 34 & 35 Vict. c. 70) and took over the ...

, which put the supervision of the Poor Law

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

under the Local Government Board

The Local Government Board (LGB) was a British Government supervisory body overseeing local administration in England and Wales from 1871 to 1919.

The LGB was created by the Local Government Board Act 1871 ( 34 & 35 Vict. c. 70) and took over the ...

. They had repealed the Ecclesiastical Titles Act

The Ecclesiastical Titles Act 1851 ( 14 & 15 Vict. c. 60) was an act of the British Parliament which made it a criminal offence for anyone outside the established "United Church of England and Ireland" to use any episcopal title "of any city, ...

and abolished the Religious test A religious test is a legal requirement to swear faith to a specific religion or sect, or to renounce the same.

In the United Kingdom

British Test Acts of 1673 and 1678

The Test Act 1673 in England obligated all persons filling any office, civ ...

s in the universities. They had introduced much-needed army reforms, instituted the abolition of the sale of commissions

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, officer's commissions in infantry and cavalry units of the English and British armies could be purchased. This avoided the need to wait to be promoted for merit or seniority, and was the usual way to obta ...

in the army and made peacetime flogging

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed ...

illegal. In foreign affairs they had settled the Alabama Claims

The ''Alabama'' Claims were a series of demands for damages sought by the government of the United States from the United Kingdom in 1869, for the attacks upon Union merchant ships by Confederate Navy commerce raiders built in British shipyard ...

by international arbitration

International arbitration can refer to arbitration between companies or individuals in different states, usually by including a provision for future disputes in a contract (typically referred to as international commercial arbitration) or betwee ...

to the benefit of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

; and kept Britain out of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

. They had introduced the Secret Ballot notwithstanding the serious opposition from the Tory party. Although parliament had passed the 1872 licensing act, Lawson had failed miserably to enact his Permissive Prohibitory Bill. In 1870, he had without success, introduced a resolution condemning the Opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

traffic, which he compared to the problems associated with alcohol: "We go on to this day merrily poisoning the Chinese

Chinese may refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people identified with China, through nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**Han Chinese, East Asian ethnic group native to China.

**'' Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic ...

with opium as we do our own people with alcohol." Lawson also voted in a minority division of two in support of Sir Charles Dilke

Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke, 2nd Baronet (4 September 1843 – 26 January 1911) was an English Liberal and Radical politician. A republican in the early 1870s, he later became a leader in the radical challenge to Whig control of the Libera ...

when heavily censured by parliament after seeking returns relating to the expenditure on the British Royal family

The British royal family comprises Charles III and other members of his family. There is no strict legal or formal definition of who is or is not a member, although the Royal Household has issued different lists outlining who is considere ...

. On 2 August 1870, at the time of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

, Lawson had opposed Gladstone, who sought parliament's permission to increase the army estimates by £2,000,000 and 20,000 men. Lawson saw the vote as a danger to Britain and represented the first step in a direction away from a policy of non-intervention

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is commonly understood as "a foreign policy of political or military non-involvement in foreign relations or in other countries' internal affairs". This is based on the grounds that a state should not inter ...

, war when not a necessity, as he emphasised, a crime and no war was justified unless strictly defensive. Although he threatened to walk through the lobbies unattended he received support from six radicals. During the election, Lawson expressed his opposition to the ongoing Ashanti war

The Anglo-Ashanti wars were a series of five conflicts that took place between 1824 and 1900 between the Ashanti Empire—in the Akan people, Akan interior of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast—and the British Empire and its African ...

which he saw as a continuation of the drive to open out Africa "We are opening out Africa to progress, civilisation and religion. I don't believe in the souls of a few being saved by destroying the bodies of many more out there. I don't believe in civilising and Christianising by the sword." Unlike many of his Liberal colleagues, Lawson was re-elected and would spend the vast majority of his time in the forthcoming parliament opposing Beaconsfieldism and what he saw as unnecessary conflict.

Beaconsfieldism

Lawson began his campaign against Disraeli'simperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

policies by opposing the annexation of the Fiji

Fiji, officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists of an archipelago of more than 330 islands—of which about ...

Islands. He supported Gladstone in his sustained attack on the British government's policy relating to the Eastern question by proposing, although unsuccessfully, Resolutions against the Vote of Credit for £6,000,000 and 20,000 men, and the calling out of the Reserve

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US v ...

. He opposed Britain's invasion of Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

, as he explained, on grounds of principle, honour, morality and justice. Between the years 1877 and 1881, Lawson was extremely busy protesting against the British government's imperial policies in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

. It began with a sustained attack against the annexation of the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

, which swiftly lead to the Zulu war

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in present-day South Africa from January to early July 1879 between forces of the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Two famous battles of the war were the Zulu victory at Isandlwana and the British defence at ...

and the role played by Sir Bartle Frere

Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere, 1st Baronet, (29 March 1815 – 29 May 1884) was a British colonial administrator. He had a successful career in India, rising to become Governor of Bombay (1862–1867). However, as High Commissioner for South ...

, the High Commissioner to the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, whom Lawson continuously asked parliament to recall. He led a successful opposition, following the death of Prince Louis Napoleon, thus preventing his burial in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. He also led a successful opposition to the annexation of Basutoland

Basutoland was a British Crown colony that existed from 1884 to 1966 in present-day Lesotho, bordered with the Cape Colony, Natal Colony and Orange River Colony until 1910 and completely surrounded by South Africa from 1910. Though the Basot ...

by the Cape colony, thus maintaining the country's eventual independence from South Africa. Lawson summarised Disraeli's policies with the following statement:

::"at the undertakings into which the Government had gone, the things they had done, or tried to do, or promised to do, or failed to do. They had set themselves up to frighten Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, protect Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, to annex the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

, to reform Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, to occupy Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, to manipulate Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, to invade Zululand, to catch Cetywayo, to smoke out Secocoeine, and to secure a scientific frontier for India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. How he asked, had they tried to do these things? They had shifted our Indian troops up and down, moved our fleet

Fleet may refer to:

Vehicles

* Fishing fleet

*Naval fleet

* Fleet vehicles, a pool of motor vehicles

* Fleet Aircraft, the aircraft manufacturing company

Places

Canada

* Fleet, Alberta, Canada, a hamlet

England

* The Fleet Lagoon, at Chesil Be ...

backwards and forwards, made secret treaties, sent ultimatums to everybody with whom they had the slightest quarrel, engaged in two cruel and unjust wars and paved the way for any number more."

Egyptian crisis

In 1880, the Carlisle constituency returned Lawson to parliament with an increased majority, while the country as a whole returned a Liberal government led by Gladstone. Lawson supported the claim of theatheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh (; 26 September 1833 – 30 January 1891) was an English political activist and atheist. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866, 15 years after George Holyoake had coined the term "secularism" in 1851.

In 1880, Br ...

, who sought religious freedom. In relation to Irish affairs, he supported Gladstone's introduction of the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881

The Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881 (44 & 45 Vict. c. 49) was the second Land Acts (Ireland), Irish land act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Background

The Liberal Party (UK), Liberal government of William Ewart Gladstone had previ ...

, only to oppose the government after Gladstone introduced the Protection of Person and Property Act 1881

The Protection of Persons and Property (Ireland) Act 1881,The Act had no official short title. It was referred to as ''Protection of Persons and Property (Ireland) Act'', or with ''Person'' in the singular, and/or with ''(Ireland)'' omitted. ( 44 ...

, which Lawson described as "starting once more on the hopeless, miserable, never-ending attempt to settle the Irish difficulty by force." In January 1881, Lawson became a leading spokesman for the Transvaal Independence Committee, from where he denounced the belligerence before applauding the negotiated settlement to end the First Boer War

The First Boer War (, ), was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and Boers of the Transvaal (as the South African Republic was known while under British ad ...

. The Egyptian crisis

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years ...

followed.

The British occupation of Egypt was the most important single act of British foreign policy during Gladstone's second administration and according to many historians has since become one of the classic case studies of the partition of Africa and of late nineteenth-century informal imperialism in general. Lawson's agitation against intervention in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

was completely in harmony with his support for the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

Boers

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

in their struggle against British rule; his support for Afghan

Afghan or Afgan may refer to:

Related to Afghanistan

*Afghans, historically refers to the Pashtun people. It is both an ethnicity and nationality. Ethnicity wise, it refers to the Pashtuns. In modern terms, it means both the citizens of Afghanist ...

tribesmen seeking to retain their independence; and his wish to see justice spread to encompass the needs of the Irish people

The Irish ( or ''Na hÉireannaigh'') are an ethnic group and nation native to the island of Ireland, who share a common ancestry, history and Culture of Ireland, culture. There have been humans in Ireland for about 33,000 years, and it has be ...

. Underlying all of these policies was an inherent distrust of the concept of empire and a cardinal belief in the traditional assertions of Cobden, that Britain should promote peace, and avoid interference in the political institutions of other nations. In many respects, Egypt was Lawson's defining moment as an anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influenc ...

radical

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

. He not only led the agitation but he disagreed with the opinions of many of his radical contemporaries, and colleagues he had and would later stand shoulder to shoulder with in agitating against similar imperialist concerns. For three long years he criticised British diplomats and argued against a government of his own making; against the European bondholders' control of the country; against the bombardment of Alexandria

The Bombardment of Alexandria in Egypt by the British Mediterranean Fleet took place on 11–13 July 1882.

Admiral Beauchamp Seymour was in command of a fleet of fifteen Royal Navy ironclad ships which had previously sailed to the harbor of Al ...

; and against the British armies destruction of the Egyptian force under Ahmed Orabi

Ahmed Urabi (; Arabic: ; 31 March 1841 – 21 September 1911), also known as Ahmed Ourabi or Orabi Pasha, was an Egyptian military officer. He was the first political and military leader in Egypt to rise from the '' fellahin'' (peasantry). Urabi ...

at the Battle of Tel el-Kebir

The Battle of Tel El Kebir (often spelled Tel-El-Kebir) was fought on 13 September 1882 at Tell El Kebir in Egypt, 110 km north-north-east of Cairo. An entrenched Egyptian force under the command of Ahmed ʻUrabi was defeated by a British ...

. He argued against parliament awarding a Vote of Thanks for Britain's military leaders; and in conjunction with Wilfrid Scawen Blunt

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (17 August 1840 – 10 September 1922), sometimes spelt Wilfred, was an English poet and writer. He and his wife Lady Anne Blunt travelled in the Middle East and were instrumental in preserving the Arabian horse bloodlines ...

campaigned for the release of Ahmed Orabi

Ahmed Urabi (; Arabic: ; 31 March 1841 – 21 September 1911), also known as Ahmed Ourabi or Orabi Pasha, was an Egyptian military officer. He was the first political and military leader in Egypt to rise from the '' fellahin'' (peasantry). Urabi ...

. On one occasion, in a blistering attack on the Government's forward policy, Lawson reminded his colleagues of their probable response had the bombardment occurred under a Conservative and not a Liberal administration.

::They would have had his right hon. friend the Secretary of State for the Home Department

The Home Office (HO), also known (especially in official papers and when referred to in Parliament) as the Home Department, is the United Kingdom's interior ministry. It is responsible for public safety and policing, border security, immigr ...

(Sir William Harcourt

Sir William George Granville Venables Vernon Harcourt, (14 October 1827 – 1 October 1904) was a British lawyer, journalist and Liberal statesman. He was Member of Parliament for Oxford, Derby, then West Monmouthshire (UK Parliament constitue ...

), (laughter and cheers) stumping the country and denouncing Government by ultimatum. They would have had the noble Marquesss, the Secretary of State for India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

( Lord Hartington) moving a Resolution condemning the proceeding's taken behind the back of Parliament. (Cheers from the Irish Members.) They would have had the President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. A committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, it was first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centur ...

(Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

) summoning the caucus. (Cheers and laughter.) They would have had the other right hon. Gentleman, the Member for Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster is a ministerial office in the Government of the United Kingdom. Excluding the prime minister, the chancellor is the highest ranking minister in the Cabinet Office, immediately after the prime minister ...

(John Bright

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade policies.

A Quaker, Bright is most famous for battling the Corn La ...

) declaiming in the Town Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

of Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

against the wicked Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

Government; and as for the Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

, they all knew there would not have been a railway train, (cheers and laughter) passing a roadside station, that he would not have pulled up to proclaim the doctrine of non-intervention

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is commonly understood as "a foreign policy of political or military non-involvement in foreign relations or in other countries' internal affairs". This is based on the grounds that a state should not inter ...

as the duty of the Government. (Laughter and cheers from the Irish Members). It was perfectly abominable to see men whom they respected, whom they believed in, whom they had placed in power, overturning every principle they had professed, carrying out a policy that was abhorrent to every lover of justice and of right.

As quickly as Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

began to solve one problem another arrived in the Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

. In 1881, an obscure tribesman and religious zealot named Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah bin Fahal (; 12 August 1843 – 21 June 1885) was a Sudanese religious and political leader. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi and led a war against Egyptian rule in Sudan, which culminated in a remarkable vi ...

, proclaimed himself the Mahdi

The Mahdi () is a figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, End of Times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad, and will appear shortly before Jesu ...

, who initiated a Jihad

''Jihad'' (; ) is an Arabic word that means "exerting", "striving", or "struggling", particularly with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it encompasses almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God in Islam, God ...

against the Egyptian military occupation. After 50,000 Mahdist tribesmen annihilated a 10,000-strong Egyptian army under the command of a reluctant British mercenary, general William Hicks Pasha, the Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

fully understood the serious nature of their involvement in Egypt. This resulted in the dispatch of General Charles George Gordon

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major-General Charles George Gordon Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, Gordon of Khartoum and General Gordon , was a British ...

to oversee the evacuation of Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile – flo ...

. After supporting a policy of "rescue and retire" Lawson quickly withdrew his support he could find no relationship between what Gladstone described as "a small service to humanity," and the killing of thousands of Arabs. After the death of Gordon, Lawson applauded Gladstone's decision to evacuate Sudan.

West Cumberland

In 1885, after the reduction of theCarlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from ) is a city in the Cumberland district of Cumbria, England.

Carlisle's early history is marked by the establishment of a settlement called Luguvalium to serve forts along Hadrian's Wall in Roman Britain. Due to its pro ...

seat to one member Lawson decided to contest the Lowther Lowther may refer to: Places

*River Lowther, Cumbria, England

*Lowther, Cumbria, civil parish in Cumbria, England

*Lowther, New Zealand, township in Southland, New Zealand

*Lowther, New South Wales, locality in Australia

*CFS Lowther, military in ...

dominated Cockermouth constituency. However, his attitude towards Gladstone's imperialist policies in Egypt had made enemies in his Cockermouth

Cockermouth is a market town and civil parish in the Cumberland unitary authority area of Cumbria, England. The name refers to the town's position by the confluence of the River Cocker into the River Derwent. At the 2021 census, the built u ...

constituency and on 5 December, the newly enfranchised electorate rejected his appeal by a small but decisive margin of ten votes. As a result, Lawson missed the parliamentary debates surrounding Irish home Rule

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of ...

and the subsequent schism of the Liberal party. Lawson was extremely critical of the newly formed Liberal Unionists

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

, particularly in the roles played by Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

and John Bright

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade policies.

A Quaker, Bright is most famous for battling the Corn La ...

. In Lawson's opinion, the turncoats had become the reactionary radical opposition and had placed Britain under the yoke of a Tory administration. He cared little for their names: Liberal Unionists

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

, Dissenting Liberals, Hartingtonians, Chamberlainites, Old Whigs, Randolphians, Tory democrats, Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

, Constitutionalists

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional to ...

, Ruling Councillors, Knight Harbingers, Union Jack

The Union Jack or Union Flag is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. The Union Jack was also used as the official flag of several British colonies and dominions before they adopted their own national flags.

It is sometimes a ...

s and Union Jackasses; they were all out and out Tories. Lawson returned to the House of Commons in the election of 1886, one of only three "Home Rulers" to capture a Conservative seat; converting a minority of ten into a majority of over one thousand. In parliament he vehemently opposed Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (; 25 July 184819 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary ...

's coercion measures.

He served as President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

of the second day of the 1887 Co-operative Congress

The Co-operative Congress is the national conference of the UK Co-operative Movement. The first of the modern congresses took place in 1869 following a series of meetings called the " Owenite Congress" in the 1830s. Members of Co-operatives UK ...

.

The Newcastle programme and the second home rule bill

In October 1891, the Liberal Party held their annual conference in the city ofNewcastle

Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England, United Kingdom

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England, United Kingdom

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area ...

, where delegates thrashed out a radical agenda to take them through the next general election, and beyond to the new century. Immediately but reluctantly endorsed by Gladstone, the Newcastle Programme as it became popularly known was a grandiose scheme that enshrined the majority of Lawson's outstanding reforms. Lawson had waited a lifetime for the realisation of these enactments, and boasted: "If the chartists could rise from their graves they would not believe that the Liberal party had absolutely homologated those great reforms."The West Cumberland Times, 20 June 1892 The election issue was no longer simply Home Rule; it was the full Newcastle programme, and Lawson was anxious to settle the Irish question to secure further domestic reforms. Back in parliament Lawson continued to support Gladstone, who introduced his Second Home Rule bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (known generally as the Second Home Rule Bill) was the second attempt made by Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland. ...

, which, except for a reduced number of Irish members at Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

mirrored its predecessor. As expected the bill's progress through Parliament was obstructed by the Opposition who emphasised all the inadequacies in the measure, which in turn justified the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...