Sir Charles Asgill, 2nd Baronet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Against his father's wishes, who offered a sizeable annual income to stay in England, Asgill entered the army on 27 February 1778, just before his 16th birthday, as an

Against his father's wishes, who offered a sizeable annual income to stay in England, Asgill entered the army on 27 February 1778, just before his 16th birthday, as an

From Lancaster Asgill was transferred to Chatham. Initially he was housed in the home of Colonel

From Lancaster Asgill was transferred to Chatham. Initially he was housed in the home of Colonel

pp. 120–121

and on 3 March 1790 he was promoted to command a company in the 1st Foot Guards, with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. Under the Duke of York he took part in the Flanders campaign in 1793. Two years later he rose to the rank of colonel, and later that year commanded a battalion of the Guards at Warley Camp, intended for foreign service.

The city of Kilkenny presented Asgill with a snuff box for his "energy and exertion" which was praised by the

The city of Kilkenny presented Asgill with a snuff box for his "energy and exertion" which was praised by the

Derbyshire Records Office hold twenty-three Asgill related records''Charles Asgill – setting the record straight''

– interview between Helen Tovey, Editor of Family Tree, and Anne Ammundsen, 7 March 2022 {{DEFAULTSORT:Asgill, Charles, 2nd Baronet 1762 births 1823 deaths Baronets in the Baronetage of Great Britain People educated at Westminster School, London British Army generals British Army personnel of the American Revolutionary War British Army personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars Devonshire Regiment officers People of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 Grenadier Guards officers American Revolutionary War prisoners of war held by the United States Equerries University of Göttingen alumni British prisoners sentenced to death Prisoners sentenced to death by the United States military Military personnel from London Burials at St James's Church, Piccadilly

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Charles Asgill, 2nd Baronet, (6 April 1762 – 23 July 1823) was a career soldier in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

. At the end of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

he became the principal of the so-called Asgill Affair of 1782, in which his retaliatory death sentence while a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

was commuted by the American forces who held him, due to the direct intervention of the government of France. Later in his career, he was involved in the Flanders campaign, the suppression of the Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 (; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ''The Turn out'', ''The Hurries'', 1798 Rebellion) was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The m ...

, and was Commander of the Eastern Division of Ireland during the Irish rebellion of 1803

The Irish rebellion of 1803 was an attempt by Irish Republicanism, Irish republicans to seize the seat of the British government in Ireland, Dublin Castle, and trigger a nationwide insurrection. Renewing the Irish Rebellion of 1798, struggle o ...

.

Early life and education

Charles Asgill was born on 6 April 1762, as the only son of a well-connected family. His father, Sir Charles Asgill, had been a formerLord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the Mayors in England, mayor of the City of London, England, and the Leader of the council, leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded Order of precedence, precedence over a ...

, and was a London banker. His mother, Sarah Theresa Pratviel, was of a French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

family, whose father was secretary to the ambassador to Spain. The family home was Richmond Place, now known as Asgill House, in Surrey. Asgill was educated at Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

and the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen (, commonly referred to as Georgia Augusta), is a Public university, public research university in the city of Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded in 1734 ...

.

Against his father's wishes, who offered a sizeable annual income to stay in England, Asgill entered the army on 27 February 1778, just before his 16th birthday, as an

Against his father's wishes, who offered a sizeable annual income to stay in England, Asgill entered the army on 27 February 1778, just before his 16th birthday, as an ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

in the 1st Foot Guards, a regiment today known as the Grenadier Guards

The Grenadier Guards (GREN GDS) is the most senior infantry regiment of the British Army, being at the top of the Infantry Order of Precedence. It can trace its lineage back to 1656 when Lord Wentworth's Regiment was raised in Bruges to protect ...

. Asgill became lieutenant in the First Foot Guards, promoted to the rank of captain, in February 1781.

The Asgill Affair

Prisoner of war

Asgill was ordered to North America at the beginning of 1781, to fight in theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. Serving under General Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805) was a British Army officer, Whig politician and colonial administrator. In the United States and United Kingdom, he is best known as one of the leading Britis ...

, he fought in the Siege of Yorktown

The siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown and the surrender at Yorktown, was the final battle of the American Revolutionary War. It was won decisively by the Continental Army, led by George Washington, with support from the Ma ...

, and became an American prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

following Cornwallis's capitulation in October 1781.

Even after the capitulation at Yorktown, violence persisted between the patriots

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

and loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

. When a loyalist named Philip White was killed by patriots, the loyalists retaliated. A captain of the Monmouth Militia and privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

, Joshua Huddy, was captured in the village of Toms River, New Jersey

Toms River is a Township (New Jersey), township and coastal town located on the Jersey Shore in Ocean County, New Jersey, Ocean County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Its mainland United States, mainland portion is also a census-designated ...

and taken to a prison in New York. Under the auspices of a prisoner exchange, Richard Lippincott took Huddy from British custody and had him hanged, by order of William Franklin

William Franklin (22 February 1730 – 17 November 1813) was an American-born attorney, soldier, politician, and colonial administrator. He was the acknowledged extra-marital son of Benjamin Franklin. William Franklin was the last colonial G ...

. New Jersey militia protested; to avoid further outbreaks of violence George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

ordered Moses Hazen

Moses Hazen (June 1, 1733 – February 5, 1803) was a brigadier general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Born in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, he saw action in the French and Indian War with Rogers' Ra ...

to select by lot a British officer likewise to be executed. His explicit orders were communicated in letters dated 3 and 18 May 1782.

On reading the letter of 18 May, James Gordon replied to Washington:

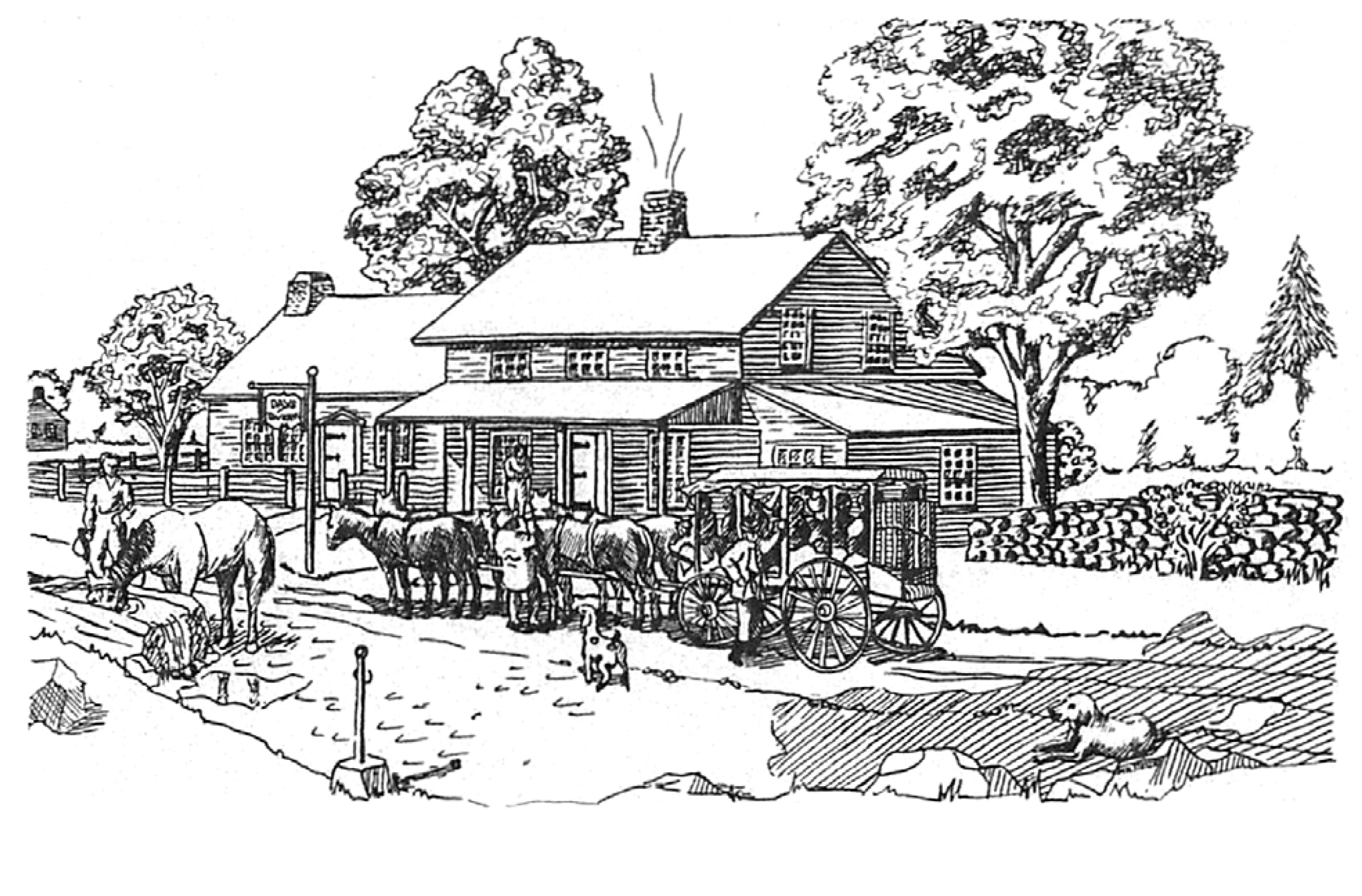

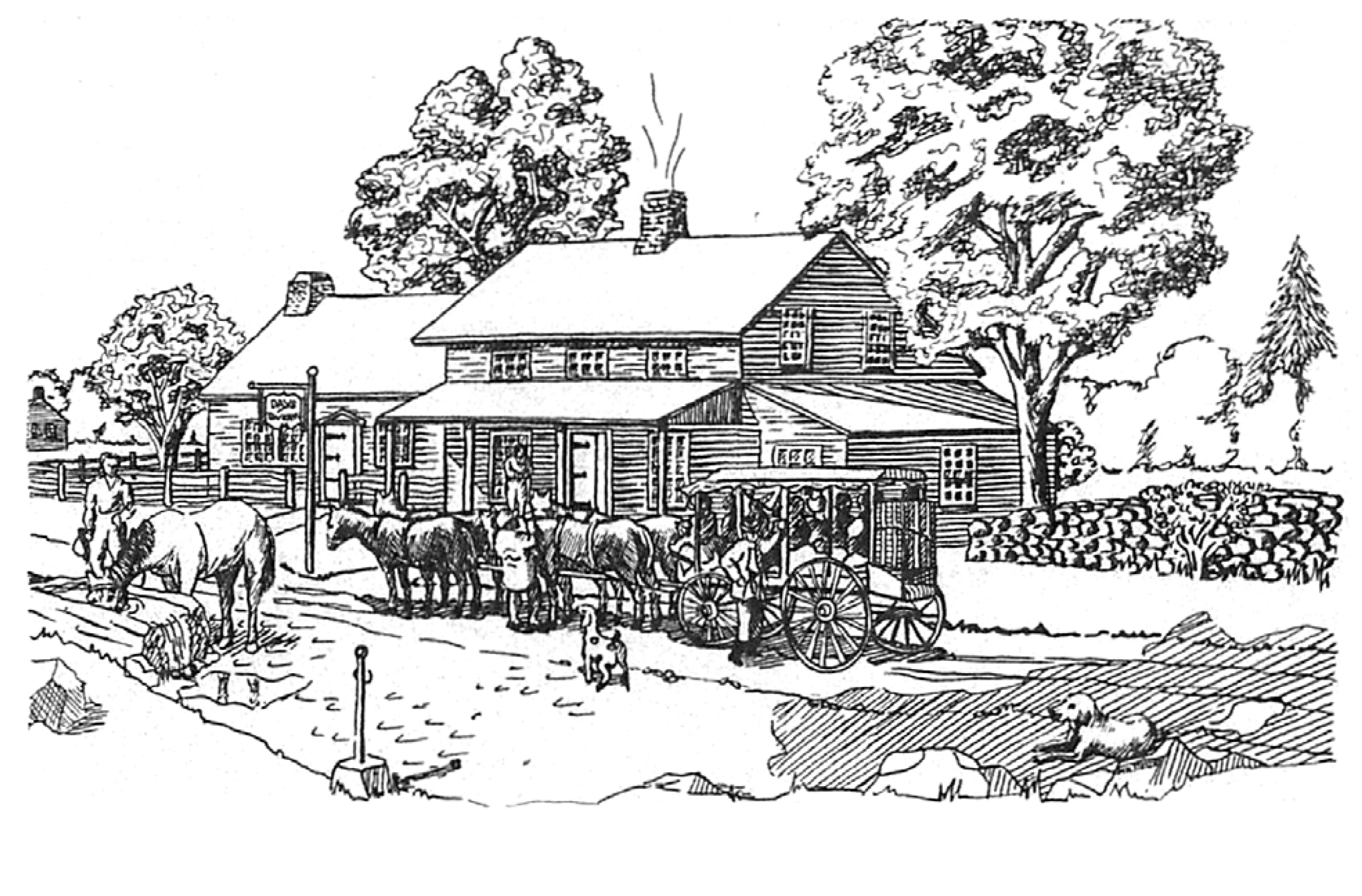

Lancaster 27th. May 1782. Sir It is with astonishment I read a Letter from your Excellency, dated 18th. May, directed to Brigadier General Hazen, Commanding at this Post, ordering him, to send a British Captain, taken at York-town, by Capitulation, with My Lord Cornwallis, Prisoner to Philadelphia, where 'tis said he is to suffer an ignominious Death, in the room of Capt. Huddy an American Officer...Hazen carried out Washington's orders on 27 May 1782. The selection was made at the Black Bear Tavern in Lancaster, where 13 British 'conditional' officers were assembled. Hazen hoped that the officers would make the selection themselves, but they refused, with one of the prisoners, Samuel Graham, writing that "With one voice we refused to have any share in a business which directly violated the terms of the treaty which placed us within General Washington's power". Lots were instead drawn by a drummer boy (some sources suggest that there were two or three drummer boys) and Asgill's was the one drawn alongside the word "unfortunate". According to William M. Fowler, as soon as Washington had given the order to take a hostage, he realised that what he had done was morally suspect and likely illegal. While Congress endorsed Washington's actions, others disagreed and

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

considered them "repugnant, wanton and unnecessary".

Soon afterwards Washington wrote to Hazen about Asgill's selection, asking why apparently available 'unconditional' prisoners were not chosen and suggesting to "remedy ..as soon as possible this Mistake".

Chatham

From Lancaster Asgill was transferred to Chatham. Initially he was housed in the home of Colonel

From Lancaster Asgill was transferred to Chatham. Initially he was housed in the home of Colonel Elias Dayton

Elias Dayton (May 1, 1737 – October 22, 1807) was an American merchant and military officer who served as captain and colonel of the local militia and in 1783 rose to become a brigadier general during the American Revolutionary War. After ...

, who commanded the Jersey Line, who treated Asgill well, especially when he became too ill to be moved. Washington ordered Asgill be held under guard. He was sent to Timothy Day's Tavern, where he suffered beatings; lack of edible food; spectators paid to watch his suffering; and deprivation of letters from his family about which he was receiving information that his father was very ill and had died. Although the British court martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

led Lippincott for Huddy's execution, he was found not guilty on the grounds that he was acting on orders from William Franklin

William Franklin (22 February 1730 – 17 November 1813) was an American-born attorney, soldier, politician, and colonial administrator. He was the acknowledged extra-marital son of Benjamin Franklin. William Franklin was the last colonial G ...

. Washington wanted Lippincott be released to the Americans in exchange for Asgill, but was refused.

During the months of Asgill's confinement, his fate drew considerable international public attention and also the direct intervention of the government of France on Asgill's behalf. Under pressure to spare Asgill, but unwilling to publicly back down from his position, Washington decided late that summer that the case had become "a great national concern, upon which an individual ought not to decide." He therefore sent the matter to be decided by the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

.

Reaction and release

When Asgill's mother, Sarah Theresa, Lady Asgill, heard about her son's fate, she turned to ministers inWhitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

and King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

became involved. She then wrote a letter to the comte de Vergennes

Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes (; 29 December 1719 – 13 February 1787) was a French statesman and diplomat. He served as Foreign Minister from 1774 to 1787 during the reign of Louis XVI of France, Louis XVI, notably during the American Wa ...

, the French Foreign Minister. Vergennes showed the letter to King Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

and Queen Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

, who in turn ordered Vergennes to write to Washington saying that any violation of the 14th Article of Capitulation would be a stain on the French nation, as well as the Americans, since both nations, along with the British, had signed that Treaty. Lady Asgill sent a copy of Vergennes' letter to Washington herself, by special courier, and her copies of correspondence reached Washington before the original from Paris.

Upon receipt of Vergennes' letter, enclosing that of Lady Asgill, Washington forwarded the correspondence to the Continental Congress, on 30 October as they were proposing to vote to hang Asgill. The letter was read aloud before the delegates. After several days of debate, on 7 November, "as a compliment to the King of France", Congress passed an Act releasing Asgill.

A week later Washington wrote a letter to Asgill, which he did not receive until 17 November 1782, enclosing a passport for him to return home on parole. Asgill left Chatham immediately that day.

Aftermath

Four years after the events of 1782, news reached Washington that Asgill was apparently spreading rumours of ill-treatment whilst in custody in America. Washington was outraged, maintaining that Asgill had been treated well. In response, Washington had his correspondence on the matter published in the ''New Haven Gazette and Connecticut Magazine'' on 16 November 1786 (with the exception of his letter of 18 May 1782 to Hazen which shows Washington's willingness to violate Article XIV of the Yorktown Articles of Capitulation). When Asgill read the account, he wrote to the editor on 20 December 1786, denying that he had spread rumours, and detailing his mistreatment while in captivity. Asgill's letter was not published until 2019, when a copy appeared in an issue of ''The Journal of Lancaster County’s Historical Society'' dedicated to the Asgill Affair. Peter Henriques writes that the Asgill Affair "could have left an ugly blot on George Washington's reputation", calling it "a blip that reminds us even the greatest of men make mistakes".Subsequent career

Asgill was appointedequerry

An equerry (; from French language, French 'stable', and related to 'squire') is an officer of honour. Historically, it was a senior attendant with responsibilities for the horses of a person of rank. In contemporary use, it is a personal attend ...

to Frederick, Duke of York in 1788; he would hold this post until his death. On 15 September 1788 he inherited the Asgill baronetcy upon the death of his father, G. E. C., ''The Complete Baronetage'', vol. V (1906pp. 120–121

and on 3 March 1790 he was promoted to command a company in the 1st Foot Guards, with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. Under the Duke of York he took part in the Flanders campaign in 1793. Two years later he rose to the rank of colonel, and later that year commanded a battalion of the Guards at Warley Camp, intended for foreign service.

Irish Rebellion of 1798

In June 1797, Asgill was appointed brigadier-general on the Staff in Ireland. He was granted the rank of major-general on 1 January 1798, and was promoted Third Major of the 1st Foot Guards in November that year. In his service records, he states he "was very actively employed against the Rebels during the Rebellion in 1798 and received the repeated thanks of the Commander of the Forces and the Government for my Conduct and Service." General Sir Charles Asgill marched fromKilkenny

Kilkenny ( , meaning 'church of Cainnech of Aghaboe, Cainnech'). is a city in County Kilkenny, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is located in the South-East Region, Ireland, South-East Region and in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinst ...

and attacked and dispersed the rebels.

The city of Kilkenny presented Asgill with a snuff box for his "energy and exertion" which was praised by the

The city of Kilkenny presented Asgill with a snuff box for his "energy and exertion" which was praised by the Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

.

On 9 May 1800 Asgill was transferred from the Foot Guards to be colonel commandant

Colonel commandant is a military title used in the armed forces of some English-speaking countries. The title, not a substantive military rank, could denote a senior colonel with authority over fellow colonels. Today, the holder often has an honor ...

of the 2nd Battalion, 46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot

The 46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1741. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 32nd (Cornwall) Regiment of Foot to form the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry in 1881, b ...

. He went onto half-pay

Half-pay (h.p.) was a term used in the British Army and Royal Navy of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries to refer to the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service.

Past usage United Kingdom

In the E ...

when the 2nd Battalion was disbanded in 1802. Later that year he was again appointed to the Staff in Ireland, commanding the garrison in Dublin and the instruction camps at the Curragh

The Curragh ( ; ) is a flat open plain in County Kildare, Ireland. This area is well known for horse breeding and training. The Irish National Stud is on the edge of Kildare town, beside the Irish National Stud#The Japanese Gardens, Japane ...

.

Service in Dublin

In 1801, before being appointed to the garrison in Dublin, Asgill found himself defending the right of Henry Ellis (in the neighbourhood of Kilkenny) to be properly remunerated for the invaluable intelligence he had provided during the rebellion. His information had made a significant contribution to the suppression of the rebels, but he paid a severe price for his loyalty after the fighting was over. His neighbours persecuted him; tried to kill him; and ruined his business as a miller. The British were very slow to pay hisannuity

In investment, an annuity is a series of payments made at equal intervals based on a contract with a lump sum of money. Insurance companies are common annuity providers and are used by clients for things like retirement or death benefits. Examples ...

of £30 per annum for life. Sir Charles Asgill and Lord Castlereagh

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, (18 June 1769 – 12 August 1822), usually known as Lord Castlereagh, derived from the courtesy title Viscount Castlereagh ( ) by which he was styled from 1796 to 1821, was an Irish-born British st ...

took up his cause (with a Mr A. Marsden) to see that he was properly compensated.

In his service records Asgill states: "On the 18th March 1803 I was reappointed to the Staff of Ireland, and placed in the Command of the Eastern District, in which the Garrison of Dublin is included; I was in Command during the Rebellion which broke out in the City in July 1803."

Asgill was promoted to lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

in January 1805.

Asgill was appointed Colonel of the Regiment

Colonel (Col) is a rank of the British Army and Royal Marines, ranking below Brigadier (United Kingdom), brigadier, and above Lieutenant colonel (United Kingdom), lieutenant colonel. British colonels are not usually field commanders; typically ...

of the 5th West India Regiment

The West India Regiments (WIR) were infantry units of the British Army recruited from and normally stationed in the British colonies of the Caribbean between 1795 and 1927. In 1888 the two West India Regiments then in existence were reduced t ...

(February 1806); of the 85th Regiment of Foot

The 85th (Bucks Volunteers) Regiment of Foot was a British Army line infantry regiment, raised in 1793. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 53rd (Shropshire) Regiment of Foot to form the King's Shropshire Light Infantry in 1881.

...

(October 1806); and of the 11th (North Devonshire) Regiment (25 February 1807), for which he raised a second battalion in the space of six months. Asgill mentions the men of the 11th in his will, in a codicil written on 15 July 1823, eight days before his death.

Asgill, having established a second battalion of the 11th Regiment of Foot, had to pay to equip his men out of his own pocket – he then experienced difficulty receiving a refund from the Treasury.

Retirement

Asgill received a letter from the Duke of York, on 3 January 1812, telling him that on account of Lieutenant General Sir John Hope's appointment to the Command of the Forces in Ireland, that "you will unavoidably be discontinued on the staff of the Army." Asgill was almost 50 years old at the time, and explains, in his reply to Colonel John McMahon, Private Secretary to the Prince Regent: "I shall for the first time in my life return to England with a reduced income, and without any employment, which is not very pleasant to my feelings after an uninterrupted service of thirty four years, fifteen of which have been spent on the Staff of Ireland." Asgill continued to serve on the Staff until 1812, and on 4 June 1814 he was promoted togeneral

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

. In 1820 he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Hanoverian Guelphic Order.

Personal life and death

On 28 August 1790 Asgill married Jemima Sophia (1770–1819), sixth daughter of Admiral Sir Chaloner Ogle, 1st Baronet. From 1791 to 1821 Asgill lived at No. 6 York Street, offSt James's Square

St James's Square is the only square in the St James's district of the City of Westminster and is a garden square. It has predominantly Georgian architecture, Georgian and Neo-Georgian architecture. For its first two hundred or so years it was ...

. The Asgills were associated with the duchess of Devonshire's circle. They enjoyed the theatre as well, frequently in the company of Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 17517 July 1816) was an Anglo-Irish playwright, writer and Whig politician who sat in the British House of Commons from 1780 to 1812, representing the constituencies of Stafford, Westminster and I ...

, a personal friend. Lady Asgill died in York Street on 30 May 1819.

Asgill died in 1823. The final two years of Asgill's life were spent at the home of his mistress, Mary Ann Goodchild, otherwise Mansel. Two codicils to his will were written and signed there shortly before his death. Upon his death, the Asgill baronetcy became extinct. One source states that Sophia bore him children.

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

* * * *Further reading

* * * Haffner, Gerald O., (1957) "Captain Charles Asgill, An Incident of 1782," ''History Today,'' vol. 7, no. 5. * Melbourne, Lady Elizabeth Milbanke Lamb (1998) ''Byron's "Corbeau Blanc" The Life and Letters of Lady Melbourne'' Edited by Jonathan David Gross. p. 412, * Pakenham, Thomas, (1969) ''The Year of Liberty: The Great Irish Rebellion of 1798.'' London: Hodder and Stoughton. * Pierce, Arthur D., (1960) ''Smugglers' Woods: Jaunts and Journeys in Colonial and Revolutionary New Jersey.'' New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. * Smith, Jayne E, (2007) ''Vicarious atonement: revolutionary justice and the Asgill case.'' New Mexico State University. * Tombs, Robert and Tombs, Isabelle, (2006) ''That Sweet Enemy: The British and the French from the Sun King to the Present.'' London: William Heinemann. *External links

Derbyshire Records Office hold twenty-three Asgill related records

– interview between Helen Tovey, Editor of Family Tree, and Anne Ammundsen, 7 March 2022 {{DEFAULTSORT:Asgill, Charles, 2nd Baronet 1762 births 1823 deaths Baronets in the Baronetage of Great Britain People educated at Westminster School, London British Army generals British Army personnel of the American Revolutionary War British Army personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars Devonshire Regiment officers People of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 Grenadier Guards officers American Revolutionary War prisoners of war held by the United States Equerries University of Göttingen alumni British prisoners sentenced to death Prisoners sentenced to death by the United States military Military personnel from London Burials at St James's Church, Piccadilly