Siege of Constantinople (674–678) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Following the disastrous

Following the disastrous

Accordingly, in 672 three great Muslim fleets were dispatched to secure the sea lanes and establish bases between Syria and the Aegean. Muhammad ibn Abdallah's fleet wintered at

Accordingly, in 672 three great Muslim fleets were dispatched to secure the sea lanes and establish bases between Syria and the Aegean. Muhammad ibn Abdallah's fleet wintered at

In 674, the Arab fleet sailed from its bases in the eastern Aegean and entered the Sea of Marmara. According to the account of Theophanes, they landed on the

In 674, the Arab fleet sailed from its bases in the eastern Aegean and entered the Sea of Marmara. According to the account of Theophanes, they landed on the  The details of the clashes around Constantinople are unclear, as Theophanes condenses the siege in his account of the first year, and the Arab chroniclers do not mention the siege at all but merely provide the names of leaders of unspecified expeditions into Byzantine territory. Thus from the Arab sources it is only known that Abdallah ibn Qays and Fadhala ibn 'Ubayd raided Crete and wintered there in 675, while in the same year Malik ibn Abdallah led a raid into Asia Minor. The Arab historians Ibn Wadih and

The details of the clashes around Constantinople are unclear, as Theophanes condenses the siege in his account of the first year, and the Arab chroniclers do not mention the siege at all but merely provide the names of leaders of unspecified expeditions into Byzantine territory. Thus from the Arab sources it is only known that Abdallah ibn Qays and Fadhala ibn 'Ubayd raided Crete and wintered there in 675, while in the same year Malik ibn Abdallah led a raid into Asia Minor. The Arab historians Ibn Wadih and

Later Arab sources dwell extensively on the events of Yazid's 669 expedition and supposed attack on Constantinople, including various mythical anecdotes, which are taken by modern scholarship to refer to the events of the 674–678 siege. Several important personalities of early Islam are mentioned as taking part, such as

Later Arab sources dwell extensively on the events of Yazid's 669 expedition and supposed attack on Constantinople, including various mythical anecdotes, which are taken by modern scholarship to refer to the events of the 674–678 siege. Several important personalities of early Islam are mentioned as taking part, such as

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

was besieged by the Arabs in 674–678, in what was the first culmination of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member o ...

's expansionist strategy against the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. Caliph Mu'awiya I

Mu'awiya I (–April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and immediately after the four Rashid ...

, who had emerged in 661 as the ruler of the Muslim Arab empire following a civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, renewed aggressive warfare against Byzantium after a lapse of some years and hoped to deliver a lethal blow by capturing the Byzantine capital of Constantinople.

As reported by the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor, the Arab attack was methodical: in 672–673 Arab fleets secured bases along the coasts of Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and then installed a loose blockade around Constantinople. They used the peninsula of Cyzicus

Cyzicus ( ; ; ) was an ancient Greek town in Mysia in Anatolia in the current Balıkesir Province of Turkey. It was located on the shoreward side of the present Kapıdağ Peninsula (the classical Arctonnesus), a tombolo which is said to have or ...

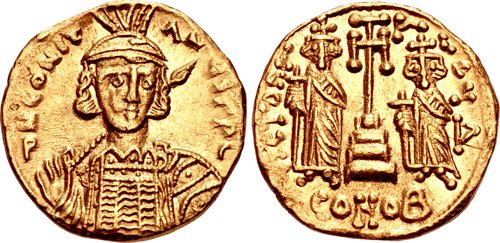

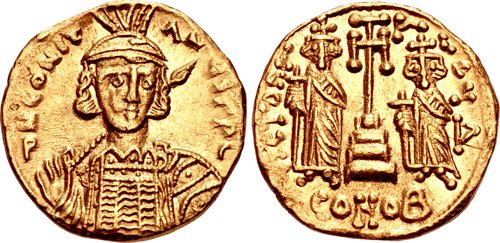

near the city as a base to spend the winter and returned every spring to launch attacks against the city's fortifications. Finally the Byzantines, under Emperor Constantine IV

Constantine IV (); 650 – 10 July 685), called the Younger () and often incorrectly the Bearded () out of confusion with Constans II, his father, was Byzantine emperor from 668 to 685. His reign saw the first serious check to nearly 50 years ...

, destroyed the Arab navy using a new invention, the liquid incendiary substance known as Greek fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon system used by the Byzantine Empire from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries. The recipe for Greek fire was a closely-guarded state secret; historians have variously speculated that it was based on saltp ...

. The Byzantines also defeated the Arab land army in Asia Minor, forcing them to lift the siege. The Byzantine victory was of major importance for the survival of the Byzantine state, as the Arab threat receded for a time. A peace treaty was signed soon after, and following the outbreak of another Muslim civil war, the Byzantines even experienced a brief period of ascendancy over the Caliphate. The siege was arguably the first major Arab defeat in 50 years of expansion and temporarily stabilized the Byzantine Empire after decades of war and defeats.

The siege left several traces in the legends of the nascent Muslim world, although it is conflated with accounts of another expedition against the city in 669, led by Mu'awiya's son, the future ruler Yazid. As a result, the veracity of Theophanes's account was questioned in 2010 by Oxford scholar James Howard-Johnston, and more recently by Marek Jankowiak. Their analyses have placed more emphasis on the Arabic and Syriac sources, but have drawn different conclusions about the dating and existence of the siege. News of a large-scale siege of Constantinople and a subsequent peace treaty reached China, where they were recorded in later histories of the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

.

Background

Following the disastrous

Following the disastrous Battle of the Yarmuk

The Battle of the Yarmuk (also spelled Yarmouk; ) was a major battle between the Byzantine army, army of the Byzantine Empire and the Arab Muslim Rashidun army, forces of the Rashidun Caliphate. The battle consisted of a series of engagements ...

in 636, the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

withdrew the bulk of its remaining forces from the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

into Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, which was shielded from the Muslim expansion by the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains (Turkish language, Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar,'' Greek language, Greek'':'' Ταύρος) are a mountain range, mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coastal reg ...

. This left the field open for the warriors of the nascent Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate () is a title given for the reigns of first caliphs (lit. "successors") — Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali collectively — believed to Political aspects of Islam, represent the perfect Islam and governance who led the ...

to complete their conquest

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or Coercion (international relations), coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or ...

of Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, with Egypt too falling shortly after. Muslim raids against the Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

n frontier zone and deep into Asia Minor began as early as 640, and continued under Mu'awiya

Mu'awiya I (–April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and immediately after the four Rashid ...

, then governor of the Levant. Mu'awiya also spearheaded the development of a Muslim navy, which within a few years grew sufficiently strong to occupy Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and raid as far as Kos, Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

and Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

. Finally, the young Muslim navy scored a crushing victory over its Byzantine counterpart in the Battle of the Masts in 655. Following the murder of Caliph Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan (17 June 656) was the third caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruling from 644 until his assassination in 656. Uthman, a second cousin, son-in-law, and notable companion of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, played a major role ...

and the outbreak of the First Muslim Civil War, Arab attacks against Byzantium stopped. In 659, Mu'awiya even concluded a truce with Byzantium, including payment of tribute to the Empire.

The peace lasted until the end of the Muslim civil war in 661, from which Mu'awiya and his clan emerged victorious, establishing the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member o ...

. From the next year, Muslim attacks recommenced, with pressure mounting as Muslim armies began wintering on Byzantine soil west of the Taurus range, maximizing the disruption caused to the Byzantine economy. These land expeditions were sometimes coupled with naval raids against the coasts of southern Asia Minor. In 668, the Arabs sent aid to Saborios, of the Armeniac Theme, who had rebelled and proclaimed himself emperor. The Arab troops under Fadala ibn Ubayd

Fadala ibn Ubayd al-Ansari (; died 673 or 678/79) was the qadi of Damascus and a commander under the Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I (). The Islamic and Byzantine sources variously report several military campaigns, including a number of naval raids, hea ...

arrived too late to assist Saborios, who had died after falling from his horse, and they spent the winter in the Hexapolis around Melitene awaiting reinforcements.

In early 669, after receiving additional troops, Fadala entered Asia Minor and advanced as far as Chalcedon

Chalcedon (; ; sometimes transliterated as ) was an ancient maritime town of Bithynia, in Asia Minor, Turkey. It was located almost directly opposite Byzantium, south of Scutari (modern Üsküdar) and it is now a district of the city of Ist ...

, on the Asian shore of the Bosporus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

across from the Byzantine capital, Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. The Arab attacks on Chalcedon were repelled, and the Arab army was decimated by famine and disease. Mu'awiya dispatched another army, led by his son (and future Caliph) Yazid, to Fadala's aid. Accounts of what followed differ. The Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor reports that the Arabs remained before Chalcedon for a while before returning to Syria, and that on their way they captured and garrisoned Amorium

Amorium, also known as Amorion (), was a city in Phrygia, Asia Minor which was founded in the Hellenistic period, flourished under the Byzantine Empire, and declined after the Sack of Amorium, Arab sack of 838. It was situated on the Byzantine m ...

. This was the first time the Arabs tried to hold a captured fortress in the interior of Asia Minor beyond the campaigning season, and probably meant that the Arabs intended to return next year and use the town as their base, but Amorium was retaken by the Byzantines during the subsequent winter. Arab sources on the other hand report that the Muslims crossed over into Europe and launched an unsuccessful attack on Constantinople itself, before returning to Syria. Given the lack of any mention of such an assault in Byzantine sources, it is most probable that the Arab chroniclers—taking account of Yazid's presence and the fact that Chalcedon is a suburb of Constantinople—"upgraded" the attack on Chalcedon to an attack on the Byzantine capital itself.

Opening moves: the campaigns of 672 and 673

The campaign of 669 clearly demonstrated to the Arabs the possibility of a direct strike at Constantinople, as well as the necessity of having a supply base in the region. This was found in the peninsula ofCyzicus

Cyzicus ( ; ; ) was an ancient Greek town in Mysia in Anatolia in the current Balıkesir Province of Turkey. It was located on the shoreward side of the present Kapıdağ Peninsula (the classical Arctonnesus), a tombolo which is said to have or ...

on the southern shore of the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara, also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, is a small inland sea entirely within the borders of Turkey. It links the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea via the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, separating Turkey's E ...

, where a raiding fleet under Fadhala ibn 'Ubayd wintered in 670 or 671. Mu'awiya now began preparing his final assault on the Byzantine capital. In contrast to Yazid's expedition, Mu'awiya intended to take a coastal route to Constantinople. The undertaking followed a careful, phased approach: first the Muslims had to secure strongpoints and bases along the coast, and then, with Cyzicus as a base, Constantinople would be blockaded by land and sea and cut off from the agrarian hinterland that supplied its food.

Accordingly, in 672 three great Muslim fleets were dispatched to secure the sea lanes and establish bases between Syria and the Aegean. Muhammad ibn Abdallah's fleet wintered at

Accordingly, in 672 three great Muslim fleets were dispatched to secure the sea lanes and establish bases between Syria and the Aegean. Muhammad ibn Abdallah's fleet wintered at Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

, a fleet under a certain Qays (perhaps Abdallah ibn Qais

Abdallah ibn Qais () (Κάϊσος, ''Kaisos'' and , ''Abdelas'' in Greek sources) was an Umayyad military leader active against the Byzantine Empire in the 670s. In ca. 672/673 he led a raid into Cilicia and Lycia, and wintered there before retur ...

) wintered in Lycia

Lycia (; Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; , ; ) was a historical region in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is today the provinces of Antalya and Muğ ...

and Cilicia, and a third fleet, under Khalid, joined them later. According to the report of Theophanes, the Emperor Constantine IV

Constantine IV (); 650 – 10 July 685), called the Younger () and often incorrectly the Bearded () out of confusion with Constans II, his father, was Byzantine emperor from 668 to 685. His reign saw the first serious check to nearly 50 years ...

(), upon learning of the Arab fleets' approach, began equipping his own fleet for war. Constantine's armament included siphon-bearing ships intended for the deployment of a newly developed incendiary substance, Greek fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon system used by the Byzantine Empire from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries. The recipe for Greek fire was a closely-guarded state secret; historians have variously speculated that it was based on saltp ...

. In 673, another Arab fleet, under Junada ibn Abi Umayya, captured Tarsus in Cilicia, as well as Rhodes. The latter, midway between Syria and Constantinople, was converted into a forward supply base and centre for Muslim naval raids. Its garrison of 12,000 men was regularly rotated back to Syria, a small fleet was attached to it for defence and raiding, and the Arabs even sowed wheat and brought along animals to graze on the island. The Byzantines attempted to obstruct the Arab plans with a naval attack on Egypt, but it was unsuccessful. Throughout this period, overland raids into Asia Minor continued, and the Arab troops wintered on Byzantine soil.

Arab attacks and related expeditions in 674–678

In 674, the Arab fleet sailed from its bases in the eastern Aegean and entered the Sea of Marmara. According to the account of Theophanes, they landed on the

In 674, the Arab fleet sailed from its bases in the eastern Aegean and entered the Sea of Marmara. According to the account of Theophanes, they landed on the Thracian

The Thracians (; ; ) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Southeast Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area that today is shared between north-eastern Greece, ...

shore near Hebdomon in April, and until September were engaged in constant clashes with the Byzantine troops. As the Byzantine chronicler reports, "Every day there was a military engagement from morning until evening, between the outworks of the Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by ...

and the Kyklobion, with thrust and counter-thrust". Then the Arabs departed and made for Cyzicus, which they captured and converted into a fortified camp to spend the winter. This set the pattern that continued throughout the siege: each spring, the Arabs crossed the Marmara and assaulted Constantinople, withdrawing to Cyzicus for the winter. In fact, the "siege" of Constantinople was a series of engagements around the city, which may even be stretched to include Yazid's 669 attack. Both Byzantine and Arab chroniclers record the siege as lasting for seven years instead of five. This can be reconciled either by including the opening campaigns of 672–673, or by counting the years until the final withdrawal of the Arab troops from their forward bases, in 680.

The details of the clashes around Constantinople are unclear, as Theophanes condenses the siege in his account of the first year, and the Arab chroniclers do not mention the siege at all but merely provide the names of leaders of unspecified expeditions into Byzantine territory. Thus from the Arab sources it is only known that Abdallah ibn Qays and Fadhala ibn 'Ubayd raided Crete and wintered there in 675, while in the same year Malik ibn Abdallah led a raid into Asia Minor. The Arab historians Ibn Wadih and

The details of the clashes around Constantinople are unclear, as Theophanes condenses the siege in his account of the first year, and the Arab chroniclers do not mention the siege at all but merely provide the names of leaders of unspecified expeditions into Byzantine territory. Thus from the Arab sources it is only known that Abdallah ibn Qays and Fadhala ibn 'Ubayd raided Crete and wintered there in 675, while in the same year Malik ibn Abdallah led a raid into Asia Minor. The Arab historians Ibn Wadih and al-Tabari

Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Jarīr ibn Yazīd al-Ṭabarī (; 839–923 CE / 224–310 AH), commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Sunni Muslim scholar, polymath, historian, exegete, jurist, and theologian from Amol, Tabaristan, present- ...

report that Yazid was dispatched by Mu'awiya with reinforcements to Constantinople in 676, and record that Abdallah ibn Qays led a campaign in 677, the target of which is unknown.

At the same time, the preoccupation with the Arab threat had reduced Byzantium's ability to respond to threats elsewhere: in Italy, the Lombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

used the opportunity to conquer most of Calabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

, including Tarentum and Brundisium, while in the Balkans, a coalition of Slavic tribes attacked the city of Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area) and the capital city, capital of the geographic reg ...

and launched seaborne raids in the Aegean, even penetrating into the Sea of Marmara.

Finally, in late 677 or early 678 Constantine IV resolved to confront the Arab besiegers in a head-on engagement. His fleet, equipped with Greek fire, routed the Arab fleet. It is probable that the death of admiral Yazid ibn Shagara, reported by Arab chroniclers for 677/678, is related to this defeat. At about the same time, the Muslim army in Asia Minor, under the command of Sufyan ibn 'Awf, was defeated by the Byzantine army under the generals Phloros, Petron and Cyprian, losing 30,000 men according to Theophanes. These defeats forced the Arabs to abandon the siege in 678. On its way back to Syria, the Arab fleet was almost annihilated in a storm off Syllaion.

The essential outline of Theophanes' account may be corroborated by the only near-contemporary Byzantine reference to the siege, a celebratory poem by the otherwise unknown Theodosius Grammaticus, which was earlier believed to refer to the second Arab siege of 717–718. Theodosius' poem commemorates a decisive naval victory before the walls of the city—with the detail that the Arab fleet too possessed fire-throwing ships—and makes a reference to "the fear of their returning shadows", which may be interpreted as confirming the recurring Arab attacks each spring from their base in Cyzicus.

Importance and aftermath

Constantinople was the nerve centre of the Byzantine state. Had it fallen, the empire's remaining provinces would have been unlikely to hold together and thus become easy prey for the Arabs. At the same time, the failure of the Arab attack on Constantinople was a momentous event in itself. It marked the culmination of Mu'awiya's campaign of attrition, which had been pursued steadily since 661. Immense resources were poured into the undertaking, including the creation of a huge fleet. Its failure had similarly important repercussions and represented a major blow to the Caliph's prestige. Conversely, Byzantine prestige reached new heights, especially in the West. Constantine IV received envoys from the Avars and the Balkan Slavs, who bore gifts and congratulations and acknowledging Byzantine supremacy. The subsequent peace also gave a much-needed respite from constant raiding to Asia Minor and allowed the Byzantine state to recover its balance and consolidate itself after the cataclysmic changes of the previous decades. The failure of the Arabs before Constantinople coincided with the increased activity of the Mardaites, a Christian group living in the mountains of Syria that resisted Muslim control and raided the lowlands. Faced with the new threat and after the immense losses suffered against the Byzantines, Mu'awiya began negotiations for a truce, with embassies exchanged between the two courts. They were drawn out until 679, which gave the Arabs time for a last raid into Asia Minor under 'Amr ibn Murra, perhaps intended to put pressure on the Byzantines. The peace treaty, of a nominal 30-year duration, provided that the Caliph would pay an annual tribute of 3,000 gold pieces, 50 horses and 50 slaves. The Arab garrisons were withdrawn from their bases on the Byzantine coastlands, including Rhodes, in 679–680. Soon after the Arab retreat from his capital, Constantine IV sent an expedition against the Slavs in the area of Thessalonica, curtailed their piracy, relieved the city and restored imperial control over the city's surroundings. After the conclusion of peace, he moved against the mounting Bulgar menace in the Balkans, but his huge army, comprising all the available forces of the empire, was decisively beaten, which opened the way for the establishment of a Bulgar state in the northeastern Balkans. In the Muslim world, after the death of Mu'awiya in 680, the various forces of opposition within the Caliphate manifested themselves. The Caliphate's division during theSecond Muslim Civil War

The Second Fitna was a period of general political and military disorder and civil war in the Islamic community during the early Umayyad Caliphate. It followed the death of the first Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I in 680, and lasted for about twelve y ...

allowed Byzantium to achieve not only peace but also a position of predominance on its eastern frontier. Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

and Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

reverted for a time to Byzantine control, and Cyprus became a condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership regime in which a building (or group of buildings) is divided into multiple units that are either each separately owned, or owned in common with exclusive rights of occupation by individual own ...

between Byzantium and the Caliphate. The peace lasted until Constantine IV's son and successor, Justinian II

Justinian II (; ; 668/69 – 4 November 711), nicknamed "the Slit-Nosed" (), was the last Byzantine emperor of the Heraclian dynasty, reigning from 685 to 695 and again from 705 to 711. Like his namesake, Justinian I, Justinian II was an ambitio ...

(), broke it in 692, with devastating consequences since the Byzantines were defeated, Justinian was deposed and a twenty-year period of anarchy followed. Muslim incursions intensified, leading to a second Arab attempt at conquering Constantinople in 717–718, which also proved unsuccessful.

Cultural impact

Ibn Abbas

ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbbās (; c. 619 – 687 CE), also known as Ibn ʿAbbās, was one of the cousins of the Prophets and messengers in Islam, prophet Muhammad. He is considered to be the greatest Tafsir#Conditions, mufassir of the Quran, Qur'an. ...

, Ibn Umar and Ibn al-Zubayr

Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam (; May 624October/November 692) was the leader of a caliphate based in Mecca that rivaled the Umayyads from 683 until his death.

The son of al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam and Asma bint Abi Bakr, and grandson of ...

. The most prominent among them in later tradition is Abu Ayyub al-Ansari

Abu Ayyub al-Ansari (, , died c. 674) — born Khalid ibn Zayd ibn Kulayb ibn Tha'laba () in Yathrib — was from the tribe of Banu Najjar, and a close companion (Arabic: الصحابه, ''sahaba'') and the standard-bearer of the Prophets and mes ...

, one of the early companions ('' Anṣār'') and standard-bearer of Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

, who died of illness before the city walls

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications such as curtain walls with to ...

during the siege and was buried there. According to Muslim tradition, Constantine IV threatened to destroy his tomb, but the Caliph warned that if he did so, the Christians under Muslim rule would suffer. Thus the tomb was left in peace, and even became a site of veneration by the Byzantines, who prayed there in times of drought. The tomb was "rediscovered" after the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

to the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks () were a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in Anatolia. Originally from Central Asia, they migrated to Anatolia in the 13th century and founded the Ottoman Empire, in which they remained socio-politically dominant for the e ...

in 1453 by the dervish

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from ) in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity (''tariqah''), or more narrowly to a religious mendicant, who chose or accepted material poverty. The latter usage is found particularly in Persi ...

Sheikh Ak Shams al-Din, and Sultan Mehmed II

Mehmed II (; , ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror (; ), was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from August 1444 to September 1446 and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

In Mehmed II's first reign, ...

() ordered the construction of a marble tomb and a mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

adjacent to it. It became a tradition that Ottoman sultans were girt with the Sword of Osman at the Eyüp mosque upon their accession. Today it remains one of the holiest Muslim shrines in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

.

This siege is even mentioned in the Chinese dynastic histories of the ''Old Book of Tang

The ''Old Book of Tang'', or simply the ''Book of Tang'', is the first classic historical work about the Tang dynasty, comprising 200 chapters, and is one of the Twenty-Four Histories. Originally compiled during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdo ...

'' and ''New Book of Tang

The ''New Book of Tang'', generally translated as the "New History of the Tang" or "New Tang History", is a work of official history covering the Tang dynasty in ten volumes and 225 chapters. The work was compiled by a team of scholars of the So ...

''.. They record that the large, well-fortified capital city of ''Fu lin'' (拂菻, i.e. Byzantium) was besieged by the ''Da shi'' (大食, i.e. the Umayyad Arabs) and their commander "Mo-yi" ( Chinese: 摩拽伐之, Pinyin

Hanyu Pinyin, or simply pinyin, officially the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet, is the most common romanization system for Standard Chinese. ''Hanyu'' () literally means 'Han Chinese, Han language'—that is, the Chinese language—while ''pinyin' ...

: ''Mó zhuāi fá zhī''), who Friedrich Hirth

Friedrich Hirth Ph.D. (16 April 1845 in Tonna, Germany, Gräfentonna, Saxe-Gotha – 10 January 1927 in Munich) was a German-American Sinology, sinologist.

Biography

He was educated at the universities of University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Humbo ...

has identified as Mu'awiya. The Chinese histories then explain that the Arabs forced the Byzantines to pay tribute afterwards as part of a peace settlement. In these Chinese sources, was directly related to the earlier , which is now considered by modern sinologists

Sinology, also referred to as China studies, is a subfield of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on China. It is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of the Chinese civilization ...

as the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. Henry Yule

Colonel (United Kingdom), Colonel Sir Henry Yule (1 May 1820 – 30 December 1889) was a Scottish Oriental studies, Orientalist and geographer. He published many travel books, including translations of the work of Marco Polo and ''Mirabil ...

remarked with some surprise the accuracy of the account in Chinese sources, which even named the negotiator of the peace settlement as 'Yenyo', or Ioannes Pitzigaudes, the unnamed envoy sent to Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

in Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English essayist, historian, and politician. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for ...

's account in which he mentions an augmentation of tributary payments a few years later due to the Umayyads facing some financial troubles.

Modern reassessment of events

The narrative of the siege accepted by modern historians relies largely on Theophanes' account, while the Arab and Syriac sources do not mention any siege but rather individual campaigns, only a few of which reached as far as Constantinople. Thus the capture of an island named Arwad "in the sea of " is recorded for 673/674, but it is unclear if it refers to the Sea of Marmara or the Aegean, and Yazid's 676 expedition is also said to have reached Constantinople. The Syriac chroniclers also disagree with Theophanes in placing the decisive battle and destruction of the Arab fleet by Greek fire in 674 during an Arab expedition against the coasts of Lycia and Cilicia, rather than Constantinople. That was followed by the landing of Byzantine forces in Syria in 677/678, which began the Mardaite uprising that threatened the Caliphate's grip on Syria enough to result in the peace agreement of 678/679. Constantin Zuckerman believes that an obscure passage in Cosmas of Jerusalem's commentary onGregory of Nazianzus

Gregory of Nazianzus (; ''Liturgy of the Hours'' Volume I, Proper of Saints, 2 January. – 25 January 390), also known as Gregory the Theologian or Gregory Nazianzen, was an early Roman Christian theologian and prelate who served as Archbi ...

, written in the early eighth century, must refer to the Arab blockade of Constantinople. It mentions how Constantine IV had ships driven (probably on wheels) across the Thracian Chersonese

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning 'b ...

from the Aegean to the Sea of Marmara, a major undertaking for imperial navy ships that makes sense only if the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

was blocked by the Arabs at Cyzicus.

Based on a re-evaluation of the original sources used by the medieval historians, the Oxford scholar James Howard-Johnston, in his 2010 book ''Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century'', rejects the traditional interpretation of events, based on Theophanes, in favour of the Syriac chroniclers' version. Howard-Johnston asserts that no siege actually took place because of not only its absence in the eastern sources but also the logistical impossibility of such an undertaking for the duration reported. Instead, he believes that the reference to a siege was a later interpolation, influenced by the events of the second Arab siege of 717–718, by an anonymous source that was later used by Theophanes. According to Howard-Johnston, "The blockade of Constantinople in the 670s is a myth which has been allowed to mask the very real success achieved by the Byzantines in the last decade of Mu'awiya's caliphate, first by sea off Lycia and then on land, through an insurgency which, before long, aroused deep anxiety among the Arabs, conscious as they were that they had merely coated the Middle East with their power".

On the other hand, the historian Marek Jankowiak argues that a major Arab siege occurred but that Theophanes (writing about 140 years after the events, based on an anonymous source, which was itself written about 50 years after the events) misdated and garbled the events and that the proper dating of the siege should be 667–669, with the major attack in early 668.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Siege of Constantinople (674-78) 670s conflicts 670s in the Byzantine Empire 674 678 Amphibious operations Constantinople 674 Constantinople 674 Constantinople 674 Constantinople 674 674 Constantinople 674 Abu Ayyub al-Ansari