Seaplane on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A seaplane is a powered

A seaplane is a powered

The Frenchman

The Frenchman

Henri Fabre (1882–1984)."

''Monash University Centre for Telecommunications and Information Engineering,'' May 15, 2002. Retrieved: 9 May 2008 Fabre's first successful take off and landing by a powered seaplane inspired other aviators, and he designed floats for several other flyers. The first hydro-aeroplane competition was held in In 1911−12, François Denhaut constructed the first seaplane with a fuselage forming a hull, using various designs to give hydrodynamic lift at take-off. Its first successful flight was on 13 April 1912.

Throughout 1910 and 1911, American pioneering aviator

In 1911−12, François Denhaut constructed the first seaplane with a fuselage forming a hull, using various designs to give hydrodynamic lift at take-off. Its first successful flight was on 13 April 1912.

Throughout 1910 and 1911, American pioneering aviator

In 1913, the ''

In 1913, the ''

At Felixstowe, Porte made advances in flying-boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch".

Porte's first design to be implemented in Felixstowe was the Felixstowe Porte Baby, a large, three-engined

At Felixstowe, Porte made advances in flying-boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch".

Porte's first design to be implemented in Felixstowe was the Felixstowe Porte Baby, a large, three-engined  The Felixstowe F.5 was intended to combine the good qualities of the F.2 and F.3, with the prototype first flying in May 1918. The prototype showed superior qualities to its predecessors but, to ease production, the production version was modified to make extensive use of components from the F.3, which resulted in lower performance than the F.2A or F.5.

Porte's final design at the Seaplane Experimental Station was the 123-foot-span five-engined Felixstowe Fury triplane (also known as the "Porte Super-Baby" or "PSB")."Felixstowe Flying-Boats."

The Felixstowe F.5 was intended to combine the good qualities of the F.2 and F.3, with the prototype first flying in May 1918. The prototype showed superior qualities to its predecessors but, to ease production, the production version was modified to make extensive use of components from the F.3, which resulted in lower performance than the F.2A or F.5.

Porte's final design at the Seaplane Experimental Station was the 123-foot-span five-engined Felixstowe Fury triplane (also known as the "Porte Super-Baby" or "PSB")."Felixstowe Flying-Boats."

''Will Higgs Co, United Kingdom.'' Retrieved: 24 December 2009. F.2, F.3, and F.5 flying boats were extensively employed by the Royal Navy for coastal patrols and to search for German

In September 1919, British company

In September 1919, British company

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies:

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies:

Many modern civilian aircraft have a floatplane variant, usually as utility transports to lakes and other remote areas. Most of these are offered as third-party modifications under a supplemental type certificate (STC), although there are several aircraft manufacturers that build floatplanes from scratch, and a few that continue to build

Many modern civilian aircraft have a floatplane variant, usually as utility transports to lakes and other remote areas. Most of these are offered as third-party modifications under a supplemental type certificate (STC), although there are several aircraft manufacturers that build floatplanes from scratch, and a few that continue to build

A seaplane is a powered

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air aircraft, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using aerodynamic lift. Fixed-wing aircraft are distinct from rotary-wing aircraft (in which a rotor mounted on a spinning shaft generate ...

capable of taking off and landing

Landing is the last part of a flight, where a flying animal, aircraft, or spacecraft returns to the ground. When the flying object returns to water, the process is called alighting, although it is commonly called "landing", "touchdown" or " spl ...

(alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteristics: floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

s and flying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

s; the latter are generally far larger and can carry far more. Seaplanes that can also take off and land on airfields are in a subclass called amphibious aircraft

An amphibious aircraft, or amphibian, is an aircraft that can Takeoff, take off and Landing, land on both solid ground and water. These aircraft are typically Fixed-wing aircraft, fixed-wing, though Amphibious helicopter, amphibious helicopte ...

, or amphibians. Seaplanes were sometimes called ''hydroplanes'', but currently this term applies instead to motor-powered watercraft that use the technique of hydrodynamic lift to skim the surface of water when running at speed.

The use of seaplanes gradually tapered off after World War II, partially because of the investments in airports during the war but mainly because landplanes were less constrained by weather conditions that could result in sea states being too high to operate seaplanes while landplanes could continue to operate. In the 21st century, seaplanes maintain a few niche uses, such as for aerial firefighting

Aerial firefighting, also known as waterbombing, is the use of aircraft and other aerial resources to Wildfire suppression, combat wildfires. The types of aircraft used include fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters. Smokejumpers and rappellers ar ...

, air transport around archipelagos, and access to undeveloped or roadless areas, some of which have numerous lakes. In British English, seaplane is sometimes used specifically to refer to a floatplane, rather than a flying boat.

Types

The word "seaplane" is used to describe two types of air/water vehicles: the floatplane and theflying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

.

* A floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

has slender floats, mounted under the fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

. Two floats are common, but other configurations are possible. Only the floats of a floatplane normally come into contact with water. The fuselage remains above water. Some small land aircraft can be modified to become float planes, and in general, floatplanes are small aircraft. Floatplanes are limited by their inability to handle wave heights typically greater than 12 inches (0.31 m). The floats add to the empty weight of the airplane and to the drag coefficient, resulting in reduced payload capacity, slower rate of climb, and slower cruise speed.

* In a flying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

, the main source of buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

is the fuselage, which acts like a ship's hull in the water because the fuselage's underside has been hydrodynamically shaped to allow water to flow around it. Most flying boats have small floats mounted on their wings to keep them stable. Not all small seaplanes have been floatplanes, but most large seaplanes have been flying boats, with their great weight supported by their hulls.

The term "seaplane" is used by some to mean "floatplane". This is the standard British usage. This article treats both flying boats and floatplanes as types of seaplane, in the US fashion.

An amphibious aircraft

An amphibious aircraft, or amphibian, is an aircraft that can Takeoff, take off and Landing, land on both solid ground and water. These aircraft are typically Fixed-wing aircraft, fixed-wing, though Amphibious helicopter, amphibious helicopte ...

can take off and land both on conventional runway

In aviation, a runway is an elongated, rectangular surface designed for the landing and takeoff of an aircraft. Runways may be a human-made surface (often asphalt concrete, asphalt, concrete, or a mixture of both) or a natural surface (sod, ...

s and water. A true seaplane can only take off and land on water. There are amphibious flying boats and amphibious floatplanes, as well as some hybrid designs, ''e.g.'', floatplanes with retractable floats.

Modern (2019) production seaplanes range in size from flying-boat type light-sport aircraft

A light-sport aircraft (LSA), or light sport aircraft, is a category of small, lightweight aircraft that are simple to fly. LSAs tend to be heavier and more sophisticated than ultralight (aka "microlight") aircraft, but LSA restrictions on weigh ...

amphibians, such as the Icon A5 and AirMax SeaMax, to the 100,000 lb ShinMaywa US-2 and Beriev Be-200

The Beriev Be-200 ''Altair'' () is a jet aircraft, jet-powered amphibious aircraft, amphibious flying boat of utility type designed and built by the Beriev, Beriev Aircraft Company. Marketed as being designed for aerial firefighting, fire figh ...

multi-role amphibians. Examples in between include the Dornier Seastar

The Dornier Seastar is a turboprop-powered amphibious aircraft built largely of composite materials. Developed by of Germany, it first flew in 1984. The design is owned by Claudius Jr's son, Conrado, who founded Dornier Seawings AG (now Dornier ...

flying-boat type, 12-seat, utility amphibian and the Canadair CL-415

The Canadair CL-415 (Super Scooper, later Bombardier 415) and the De Havilland Canada DHC-515 are a series of amphibious aircraft built originally by Canadair and subsequently by Bombardier and De Havilland Canada. The CL-415 is based on the ...

amphibious water-bomber. The Viking Air DHC-6 Twin Otter and Cessna Caravan

The Cessna 208 Caravan is a utility aircraft produced by Cessna.

The project was commenced on November 20, 1981, and the prototype first flew on December 9, 1982.

The production model was certified by the FAA in October 1984 and its Cargoma ...

utility aircraft have landing gear options which include amphibious floats.

History

Taking off on water was attempted by some early flight attempts, but water take off and landing began in earnest in the 1910s and seaplanes pioneered transatlantic routes, and were used in World War I. They continued to develop before World War II, and had widespread use. After World War II, the creation of so many land airstrips meant water landings began to drift into special applications. They continued in niches such as access in remote areas, forest fire fighting, and maritime patrol.Early pioneers

The Frenchman

The Frenchman Alphonse Pénaud

Alphonse Pénaud (31 May 1850 – 22 October 1880), was a 19th-century French pioneer of aviation design and engineering. He was the originator of the use of twisted rubber to power model aircraft, and his 1871 model airplane, which he called ...

filed the first patent for a flying machine with a boat hull and retractable landing gear in 1876, but Austrian Wilhelm Kress

Wilhelm Kress (29 July 1836 in Saint Petersburg – 24 February 1913 in Vienna) Born of German (Bavarian) parents in St. Petersburg in 1836. Moved to Vienna in 1873, where his self-propelled flying models attracted much attention. He became a na ...

is credited with building the first seaplane, '' Drachenflieger,'' in 1898, although its two Daimler engines were inadequate for take-off, and it later sank when one of its two floats collapsed.''Flying Boats & Seaplanes: A History from 1905'', Stéphane Nicolaou pp. 10, 15-17, 24

On 6 June 1905, Gabriel Voisin took off and landed on the River Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plat ...

with a towed kite glider on floats. The first of his unpowered flights was . He later built a powered floatplane in partnership with Louis Blériot

Louis Charles Joseph Blériot ( , also , ; 1 July 1872 – 1 August 1936) was a French aviator, inventor, and engineer. He developed the first practical headlamp for cars and established a profitable business manufacturing them, using much of t ...

, but the machine was unsuccessful.

Other pioneers also attempted to attach floats to aircraft in Britain, Australia, France and the United States.

On 28 March 1910, Frenchman Henri Fabre flew the first successful powered seaplane, the Gnome Omega

The Gnome 7 Omega (commonly called the Gnome 50 hp) is a French seven-cylinder, air-cooled aero engine produced by Gnome et Rhône. It was shown at the Paris Aero Salon held in December 1908 and was first flown in 1909. It was the world's ...

-powered ''hydravion'', a trimaran floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

.Naughton, RussellHenri Fabre (1882–1984)."

''Monash University Centre for Telecommunications and Information Engineering,'' May 15, 2002. Retrieved: 9 May 2008 Fabre's first successful take off and landing by a powered seaplane inspired other aviators, and he designed floats for several other flyers. The first hydro-aeroplane competition was held in

Monaco

Monaco, officially the Principality of Monaco, is a Sovereign state, sovereign city-state and European microstates, microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria, in Western Europe, ...

in March 1912, featuring aircraft using floats from Fabre, Curtiss, Tellier and Farman. This led to the first scheduled seaplane passenger services, at Aix-les-Bains

Aix-les-Bains (, ; ; ), known locally and simply as Aix, is a Communes of France, commune in the southeastern French Departments of France, department of Savoie.French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

ordered its first floatplane in 1912. On May 10, 1912 Glenn L. Martin flew a homemade seaplane in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, setting records for distance and time.

In 1911−12, François Denhaut constructed the first seaplane with a fuselage forming a hull, using various designs to give hydrodynamic lift at take-off. Its first successful flight was on 13 April 1912.

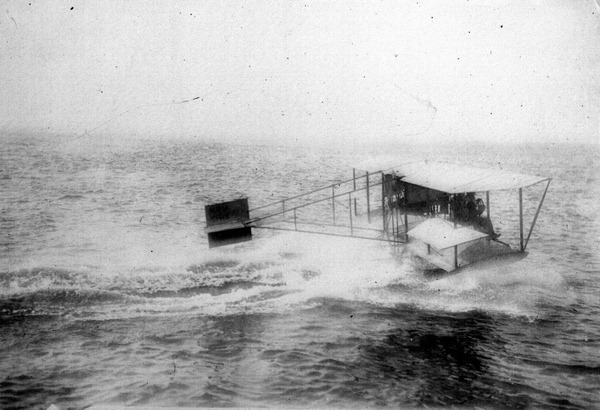

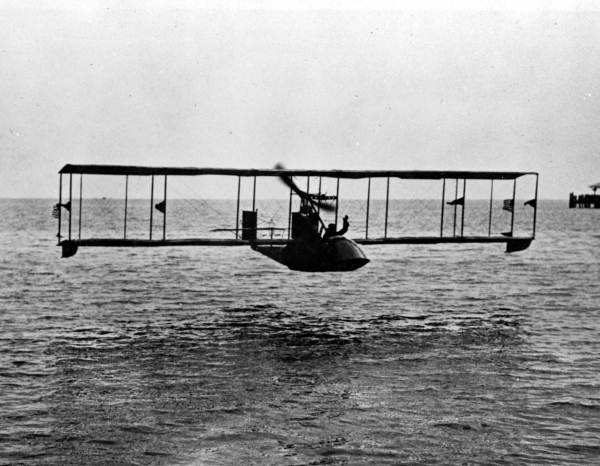

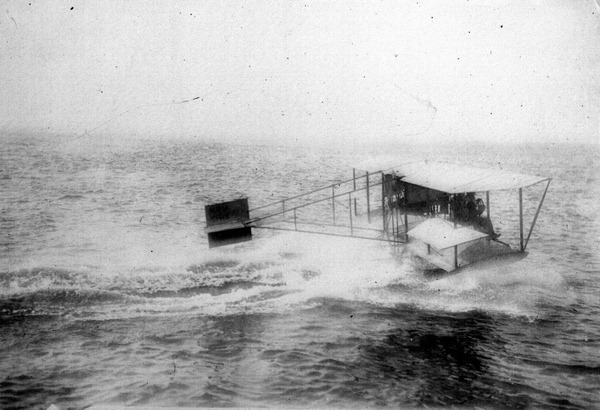

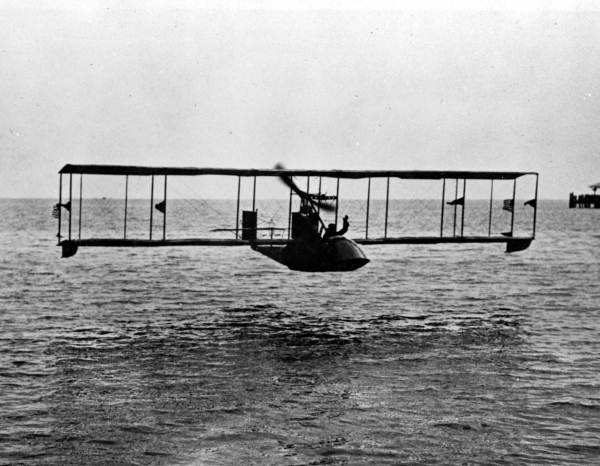

Throughout 1910 and 1911, American pioneering aviator

In 1911−12, François Denhaut constructed the first seaplane with a fuselage forming a hull, using various designs to give hydrodynamic lift at take-off. Its first successful flight was on 13 April 1912.

Throughout 1910 and 1911, American pioneering aviator Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early a ...

developed his floatplane into the successful Curtiss Model D

The 1911 Curtiss Model D (or frequently "Curtiss Pusher") is an early United States pusher aircraft with the engine and propeller behind the pilot's seat. It was among the first aircraft in the world to be built in any quantity, during an era o ...

land-plane, which used a larger central float and sponsons. Combining floats with wheels, he made the first amphibian flights in February 1911 and was awarded the first Collier Trophy

The Robert J. Collier Trophy is awarded annually "for the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics in America, with respect to improving the performance, efficiency, and safety of air or space vehicles, the value of which has been t ...

for US flight achievement. From 1912, his experiments with a hulled seaplane resulted in the 1913 Model E and Model F, which he called "flying-boats".

In February 1911, the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

took delivery of the Curtiss Model E

The Curtiss Model E is an early aircraft developed by Glenn Curtiss in the United States in 1911.

Design

Essentially a refined and enlarged version of the later "headless" Curtiss Model D, Model D, variants of the Model E made important step ...

and soon tested landings on and take-offs from ships, using the Curtiss Model D.

There were experiments by aviators to adapt the Wright Model B to a water landing. The first motion picture recorded from an airplane was from a Wright Model B floatplane, by Frank Coffyn in 1911. The Wright Brothers, widely celebrated for their breakthrough aircraft designs, were slower to develop a seaplane; Wilbur died in 1912, and the company was bogged down in lawsuits. However, by 1913, the Wright Brother company developed the Wright Model CH Flyer. In 1913, the Wright company also came out withe Wright Model G Aerboat, which was a seaplane with an enclosed cabin (a first for the company);the chief engineer of this version was Grover Loening.

In Britain, Captain Edward Wakefield and Oscar Gnosspelius began to explore the feasibility of flight from water in 1908. They decided to make use of Windermere

Windermere (historically Winder Mere) is a ribbon lake in Cumbria, England, and part of the Lake District. It is the largest lake in England by length, area, and volume, but considerably smaller than the List of lakes and lochs of the United Ki ...

in the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

, England's largest lake

A lake is often a naturally occurring, relatively large and fixed body of water on or near the Earth's surface. It is localized in a basin or interconnected basins surrounded by dry land. Lakes lie completely on land and are separate from ...

. The latter's first attempts to fly attracted large crowds, though the aircraft failed to take off and required a re-design of the floats incorporating features from the boat hulls of the lake's motor boat racing club member Isaac Borwick. Meanwhile, Wakefield ordered a floatplane similar to the design of the 1910 Fabre Hydravion. By November 1911, both Gnosspelius and Wakefield had aircraft capable of flight from water and awaited suitable weather conditions. Gnosspelius's flight was short-lived, as the aircraft crashed into the lake. Wakefield's pilot, however, taking advantage of a light northerly wind, successfully took off and flew at a height of to Ferry Nab, where he made a wide turn and returned for a perfect landing on the lake's surface.

In Switzerland, Émile Taddéoli equipped the Dufaux 4 biplane with swimmers and successfully took off in 1912. A seaplane was used during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

in 1913, when a Greek "Astra Hydravion" did a reconnaissance of the Turkish fleet and dropped four bombs.

Birth of an industry

Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

'' newspaper put up a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic, which was soon "enhanced by a further sum" from the ''Women's Aerial League of Great Britain''.

American businessman Rodman Wanamaker

Lewis Rodman Wanamaker (February 13, 1863 – March 9, 1928) was an American businessman and heir to the Wanamaker's department store fortune. In addition to operating stores in Philadelphia, New York City, and Paris, he was a patron of the ar ...

became determined that the prize should go to an American aircraft and commissioned the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (1909–1929) was an American aircraft manufacturer originally founded by Glenn Curtiss, Glenn Hammond Curtiss and Augustus Moore Herring in Hammondsport, New York. After significant commercial success in ...

to design and build an aircraft capable of making the flight. Curtiss's development of the ''Flying Fish'' flying boat in 1913 brought him into contact with John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Colonel John Cyril Porte, (26 February 1884 – 22 October 1919) was a British flying boat aviation pioneer, pioneer associated with the First World War Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.

Early life and career

Porte was b ...

, a retired Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

Lieutenant, aircraft designer and test pilot who was to become an influential British aviation pioneer. Recognising that many of the early accidents were attributable to a poor understanding of handling while in contact with the water, the pair's efforts went into developing practical hull designs to make the transatlantic crossing possible.The Felixstowe Flying Boats, ''Flight'' 2 December 1955

The two years before World War I's breakout also saw the privately produced pair of Benoist XIV __NOTOC__

The Benoist XIV, also called ''The Lark of Duluth'', was a small biplane flying boat built in the United States in 1913 in the hope of using it to carry paying passengers. The two examples built were used to provide the first heavier-th ...

biplane flying boats, designed by Thomas W. Benoist

Thomas W. Benoist (December 29, 1874 – June 14, 1917) was an American aviator and aircraft manufacturer. In an aviation career of only ten years, he formed the world's first aircraft parts distribution company, established one of the leading e ...

, initiate the start of the first heavier-than-air airline service anywhere in the world, and the first airline service of any kind at all in the United States.

At the same time, the British boat-building firm J. Samuel White

J. Samuel White was a British shipbuilding firm based in Cowes, taking its name from John Samuel White (1838–1915).

It came to prominence during the Victorian era. During the 20th century it built destroyers and other naval craft for both the ...

of Cowes

Cowes () is an England, English port, seaport town and civil parish on the Isle of Wight. Cowes is located on the west bank of the estuary of the River Medina, facing the smaller town of East Cowes on the east bank. The two towns are linked b ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

set up a new aircraft division and produced a flying boat in the United Kingdom. This was displayed at the London Air Show at Olympia in 1913.Hull, Norman. ''Flying Boats of the Solent: A Portrait of a Golden Age of Air Travel'' (Aviation Heritage). Great Addington, Kettering, Northants, UK: Silver Link Publishing, 2002. . In that same year, a collaboration between the S. E. Saunders boatyard of East Cowes

East Cowes is a town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the north of the Isle of Wight, on the east bank of the River Medina, next to its west bank neighbour Cowes. It has a population of 8,428 according to the United Kingdom Census ...

and the Sopwith Aviation Company

The Sopwith Aviation Company was a British aircraft company that designed and manufactured aeroplanes mainly for the British Royal Naval Air Service, the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force during the First World War, most famously ...

produced the "Bat Boat", an aircraft with a consuta

Consuta was a form of construction of watertight hulls for boats and marine aircraft, comprising four Wood veneer, veneers of mahogany planking interleaved with waterproofed Calico (textile), calico and stitched together with copper wire. The na ...

laminated hull that could operate from land or on water, which today is called an amphibious aircraft

An amphibious aircraft, or amphibian, is an aircraft that can Takeoff, take off and Landing, land on both solid ground and water. These aircraft are typically Fixed-wing aircraft, fixed-wing, though Amphibious helicopter, amphibious helicopte ...

. The "Bat Boat" completed several landings on sea and on land and was duly awarded the Mortimer Singer Prize. It was the first all-British aeroplane capable of making six return flights over five miles within five hours.

In the US, Wanamaker's commission built on Glen Curtiss's previous development and experience with the Curtiss Model F for the U.S. Navy, which rapidly resulted in the ''America'', designed under Porte's supervision following his study and rearrangement of the flight plan; the aircraft was a conventional biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

design with two-bay, unstaggered wings of unequal span with two pusher inline engines mounted side-by-side above the fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

in the interplane gap. Wingtip pontoons were attached directly below the lower wings near their tips. The design (later developed into the Model H) resembled Curtiss's earlier flying boats but was built considerably larger so it could carry enough fuel to cover . The three crew members were accommodated in a fully enclosed cabin.

Trials of the ''America'' began 23 June 1914 with Porte also as Chief Test Pilot; testing soon revealed serious shortcomings in the design; it was under-powered, so the engines were replaced with more powerful tractor engines. There was also a tendency for the nose of the aircraft to try to submerge as engine power increased while taxiing on water. This phenomenon had not been encountered before, since Curtiss's earlier designs had not used such powerful engines nor large fuel/cargo loads and so were relatively more buoyant. In order to counteract this effect, Curtiss fitted fins

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foil (fluid mechanics), foils that produce lift (force), lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while travelin ...

to the sides of the bow to add hydrodynamic lift, but soon replaced these with sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, Instantaneous stability, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercra ...

s, a type of underwater pontoon mounted in pairs on either side of a hull. These sponsons (or their engineering equivalents) and the flared, notched hull would remain a prominent feature of flying-boat hull design in the decades to follow. With the problem resolved, preparations for the crossing resumed. While the craft was found to handle "heavily" on takeoff, and required rather longer take-off distances than expected, the full moon on 5 August 1914 was selected for the trans-Atlantic flight; Porte was to pilot the ''America'' with George Hallett as co-pilot and mechanic.

World War I (1914–1918)

Curtiss and Porte's plans were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. Porte sailed for England on 4 August 1914 and rejoined the Navy as a member of theRoyal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British ...

. Appointed Squadron Commander of Royal Navy Air Station Hendon, he soon convinced the Admiralty of the potential of flying boats and was put in charge of the naval air station

A Naval Air Station (NAS) is a military air base, and consists of a permanent land-based operations locations for the military aviation division of the relevant branch of a navy (Naval aviation). These bases are typically populated by squadron ...

at Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town and civil parish in the East Suffolk District, East Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest Containerization, containe ...

in 1915. Porte persuaded the Admiralty to commandeer (and later, purchase) the ''America'' and a sister craft from Curtiss. This was followed by an order for 12 more similar aircraft, one Model H-2 and the remaining as Model H-4s. Four examples of the latter were assembled in the UK by Saunders

Saunders is a surname of English and Scottish origin, derived from ''Sander'', a mediaeval form of Alexander.See also: Sander (name)

People

* Ab Saunders (1851–1883), American cowboy and gunman

* Al Saunders (born 1947), American football c ...

. All of these were similar to the design of the ''America'' and, indeed, were all referred to as ''America''s in Royal Navy service. The engines, however, were changed from the under-powered 160 hp Curtiss engines to 250 hp Rolls-Royce Falcon

The Rolls-Royce Falcon is an aircraft engine, aero engine developed in 1915. It was a smaller version of the Rolls-Royce Eagle, a liquid-cooled V-12 of 867 Cubic inch, cu in (14.2 Litre, L) Engine displacement, capacity. Fitted to many British ...

engines. The initial batch was followed by an order for 50 more (totalling 64 ''Americas'' overall during the war). Porte also acquired permission to modify and experiment with the Curtiss aircraft.

The Curtiss H-4s were soon found to have a number of problems; they were underpowered, their hulls were too weak for sustained operations, and they had poor handling characteristics when afloat or taking off.Bruce ''Flight'' 2 December 1955, p. 844.London 2003, pp. 16–17. One flying boat pilot, Major Theodore Douglas Hallam, wrote that they were "comic machines, weighing well under two tons; with two comic engines giving, when they functioned, 180 horsepower; and comic control, being nose heavy with engines on and tail heavy in a glide."Hallam 1919, pp. 21–22.

At Felixstowe, Porte made advances in flying-boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch".

Porte's first design to be implemented in Felixstowe was the Felixstowe Porte Baby, a large, three-engined

At Felixstowe, Porte made advances in flying-boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch".

Porte's first design to be implemented in Felixstowe was the Felixstowe Porte Baby, a large, three-engined biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

flying boat, powered by one central pusher and two outboard tractor Rolls-Royce Eagle

The Rolls-Royce Eagle was the first aircraft engine to be developed by Rolls-Royce Limited. Introduced in 1915 to meet British military requirements during World War I, it was used to power the Handley Page Type O bombers and a number of oth ...

engines.

Porte modified an H-4 with a new hull whose improved hydrodynamic qualities made taxiing, take-off and landing much more practical and called it the Felixstowe F.1.

Porte's innovation of the "Felixstowe notch" enabled the craft to overcome suction from the water more quickly and break free for flight much more easily. This made operating the craft far safer and more reliable. The "notch" breakthrough would soon after evolve into a "step", with the rear section of the lower hull sharply recessed above the forward lower hull section, and that characteristic became a feature of both flying-boat hulls and seaplane floats. The resulting aircraft would be large enough to carry sufficient fuel to fly long distances and could berth alongside ships to take on more fuel.

Porte then designed a similar hull for the larger Curtiss H-12 flying boat which, while larger and more capable than the H-4s, shared failings of a weak hull and poor water handling. The combination of the new Porte-designed hull, this time fitted with two steps, with the wings of the H-12 and a new tail, and powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle

The Rolls-Royce Eagle was the first aircraft engine to be developed by Rolls-Royce Limited. Introduced in 1915 to meet British military requirements during World War I, it was used to power the Handley Page Type O bombers and a number of oth ...

engines, was named the Felixstowe F.2 and first flew in July 1916,London 2003, pp. 24–25. proving greatly superior to the Curtiss on which it was based. It was used as the basis for all future designs.Bruce ''Flight'' 2 December 1955, p. 846. It entered production as the Felixstowe F.2A, being used as a patrol aircraft, with about 100 being completed by the end of World War I. Another seventy were built, and these were followed by two F.2c, which were built at Felixstowe.

In February 1917, the first prototype of the Felixstowe F.3 was flown. It was larger and heavier than the F.2, giving it greater range and heavier bomb load, but poorer agility. Approximately 100 Felixstowe F.3s were produced before the end of the war.

The Felixstowe F.5 was intended to combine the good qualities of the F.2 and F.3, with the prototype first flying in May 1918. The prototype showed superior qualities to its predecessors but, to ease production, the production version was modified to make extensive use of components from the F.3, which resulted in lower performance than the F.2A or F.5.

Porte's final design at the Seaplane Experimental Station was the 123-foot-span five-engined Felixstowe Fury triplane (also known as the "Porte Super-Baby" or "PSB")."Felixstowe Flying-Boats."

The Felixstowe F.5 was intended to combine the good qualities of the F.2 and F.3, with the prototype first flying in May 1918. The prototype showed superior qualities to its predecessors but, to ease production, the production version was modified to make extensive use of components from the F.3, which resulted in lower performance than the F.2A or F.5.

Porte's final design at the Seaplane Experimental Station was the 123-foot-span five-engined Felixstowe Fury triplane (also known as the "Porte Super-Baby" or "PSB")."Felixstowe Flying-Boats."''Will Higgs Co, United Kingdom.'' Retrieved: 24 December 2009. F.2, F.3, and F.5 flying boats were extensively employed by the Royal Navy for coastal patrols and to search for German

U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s.

In 1918, they were towed on lighters towards the northern German ports to extend their range; on 4 June 1918, this resulted in three F.2As engaging in a dogfight with ten German seaplanes, shooting down two confirmed and four probables at no loss. As a result of this action, British flying boats were dazzle-painted to aid identification in combat.

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (1909–1929) was an American aircraft manufacturer originally founded by Glenn Curtiss, Glenn Hammond Curtiss and Augustus Moore Herring in Hammondsport, New York. After significant commercial success in ...

independently developed its designs into the small Model F, the larger Model K (several of which were sold to the Russian Naval Air Service), and the Model C for the U.S. Navy. Curtiss, among others, also built the Felixstowe F.5 as the Curtiss F5L, based on the final Porte hull designs and powered by American Liberty engine

The Liberty L-12 is an American water-cooled 45° V-12 engine, displacing and making , designed for a high power-to-weight ratio and ease of mass production. It was designed principally as an aircraft engine and saw wide use in aero applicat ...

s.

Meanwhile, the pioneering flying-boat designs of François Denhaut had been steadily developed by the Franco-British Aviation Company into a range of practical craft. Smaller than the Felixstowes, several thousand FBAs served with almost all of the Allied forces as reconnaissance craft, patrolling the North Sea, Atlantic and Mediterranean Oceans.

In Italy, several seaplanes were developed, starting with the L series and progressing with the M series. The Macchi M.5, in particular, was extremely manoeuvrable and agile and matched the land-based aircraft it had to fight. Two hundred forty-four were built in total.

Towards the end of World War I, the aircraft were flown by Italian Navy Aviation, United States Navy and United States Marine Corps airmen. Ensign Charles Hammann won the first Medal of Honor awarded to a United States naval aviator in an M.5

The German aircraft manufacturing company Hansa-Brandenburg built flying boats starting with the model Hansa-Brandenburg GW in 1916, and had a degree of military success with their Hansa-Brandenburg W.12 two-seat floatplane fighter the following year, being the primary aircraft flown by Imperial Germany's maritime fighter ace, Friedrich Christiansen. The Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

firm Lohner-Werke

Bombardier Transportation Austria GmbH is an Austrian subsidiary company of Bombardier Transportation located in Vienna, Austria.

It was founded in the 19th century by Jacob Lohner as Lohner-Werke or simply ''Lohner'' as a luxury coachbuilding f ...

began building flying boats, starting with the Lohner E in 1914 and the later (1915) widely copied Lohner L

The Lohner L was a reconnaissance flying boat produced in Austria-Hungary during World War I. It was a two-bay biplane of typical configuration for the flying boats of the day, with its Pusher configuration, pusher engine mounted on struts in th ...

.

Between the wars

In September 1919, British company

In September 1919, British company Supermarine

Supermarine was a British aircraft manufacturer. It is most famous for producing the Spitfire fighter plane during World War II. The company built a range of seaplanes and flying boats, winning the Schneider Trophy for seaplanes with three cons ...

started operating the first flying-boat service in the world, from Woolston to Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, but it was short-lived.

A Curtiss NC-4 became the first airplane to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in 1919, crossing with multiple stops via the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

. Of the four that made the attempt, only one completed the flight.

In 1923, the first successful commercial flying-boat service was introduced, with flights to and from the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

. After frequent appeals by the industry for subsidies, the Government decided that nationalization was necessary and ordered five aviation companies to merge to form the state-owned Imperial Airways

Imperial Airways was an early British commercial long-range airline, operating from 1924 to 1939 and principally serving the British Empire routes to South Africa, India, Australia and the Far East, including Malaya and Hong Kong. Passengers ...

of London (IAL). IAL became the international flag-carrying British airline, providing flying-boat passenger and mail-transport links between Britain and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

using aircraft such as the Short S.8 Calcutta.

In 1928, four Supermarine Southampton

The Supermarine Southampton was a flying boat of the interwar period designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Supermarine. It was one of the most successful flying boats of the era.

The Southampton was derived from the expe ...

flying boats of the RAF Far East flight arrived in Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. The flight was considered proof that flying boats had become a reliable means of long-distance transport.

In the 1930s, flying boats made it possible to have regular air transport between the U.S. and Europe, opening up new air travel routes to South America, Africa, and Asia. Foynes

Foynes (; ) is a town and major port in County Limerick in the midwest of Ireland, located at the edge of hilly land on the southern bank of the Shannon Estuary. The population of the town was 512 as of the 2022 census.

Foynes's role as sea ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

and Botwood, Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the populatio ...

were the terminals for many early transatlantic flights. In areas where there were no airfields for land-based aircraft, flying boats could stop at small river, lake or coastal stations to refuel and resupply. The Pan Am

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and more commonly known as Pan Am, was an airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States for ...

Boeing 314 "Clipper" flying boats brought new exotic destinations like the Far East within reach and came to represent the romance of flight.

By 1931, mail from Australia was reaching Britain in 16 days, or less than half the time taken by sea. In that year, government tenders on both sides of the world invited applications to run new passenger and mail services between the ends of the Empire, and Qantas

Qantas ( ), formally Qantas Airways Limited, is the flag carrier of Australia, and the largest airline by fleet size, international flights, and international destinations in Australia and List of largest airlines in Oceania, Oceania. A foundi ...

and IAL were successful with a joint bid. A company under combined ownership was then formed, Qantas Empire Airways. The new ten-day service between Rose Bay, New South Wales

Rose Bay is a harbourside Eastern Suburbs (Sydney), eastern suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Rose Bay is located seven kilometres east of the Sydney central business district, in the Local government in Australia, lo ...

, (near Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

) and Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

was such a success that the volume of mail soon exceeded aircraft storage space.

A solution was found by the British government, who had requested Short Brothers

Short Brothers plc, usually referred to as Shorts or Short, is an aerospace company based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Shorts was founded in 1908 in London, and was the first company in the world to make production aeroplanes. It was particu ...

to design a large long-range monoplane for IAL in 1933. Partner Qantas purchased six Short Empire flying boats.

Delivering the mail as quickly as possible generated much competition and some innovative designs. One variant of the Short Empire flying boats was the strange-looking ''Maia'' and ''Mercury''. It was a four-engined floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

''Mercury'' (the winged messenger) fixed on top of ''Maia'', a heavily modified Short Empire flying boat. The larger Maia took off, carrying the smaller Mercury loaded to a weight greater than it could take off with. This allowed the Mercury to carry sufficient fuel for a direct trans-Atlantic flight with the mail. Unfortunately, this was too complex, and the Mercury had to be returned from America by ship. The Mercury did set some distance records before in-flight refuelling was adopted.

Sir Alan Cobham devised a method of in-flight refuelling in the 1930s. In the air, the Short Empire could be loaded with more fuel than it could take off with. Short Empire flying boats serving the trans-Atlantic crossing were refueled over Foynes; with the extra fuel load, they could make a direct trans-Atlantic flight. A Handley Page H.P.54 Harrow was used as the fuel tanker.

The German Dornier Do X flying boat was noticeably different from its UK and U.S.-built counterparts. It had wing-like protrusions from the fuselage, called sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, Instantaneous stability, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercra ...

s, to stabilize it on the water without the need for wing-mounted outboard floats. This feature was pioneered by Claudius Dornier

Claude (Claudius) Honoré Désiré Dornier (14 May 1884 – 5 December 1969) was a France–Germany relations, Franco-German airplane designer and founder of Dornier GmbH. His notable designs include the 12-engine Dornier Do X flying boat, f ...

during World War I on his Dornier Rs. I giant flying boat and perfected on the Dornier Wal in 1924. The enormous Do X was powered by 12 engines and carried 170 people. It flew across the Atlantic to the Americas in 1929, It was the largest flying boat of its time, but was severely underpowered and was limited by a very low operational ceiling. Only three were built, with a variety of engines installed, in an attempt to overcome the lack of power. Two of these were sold to Italy.

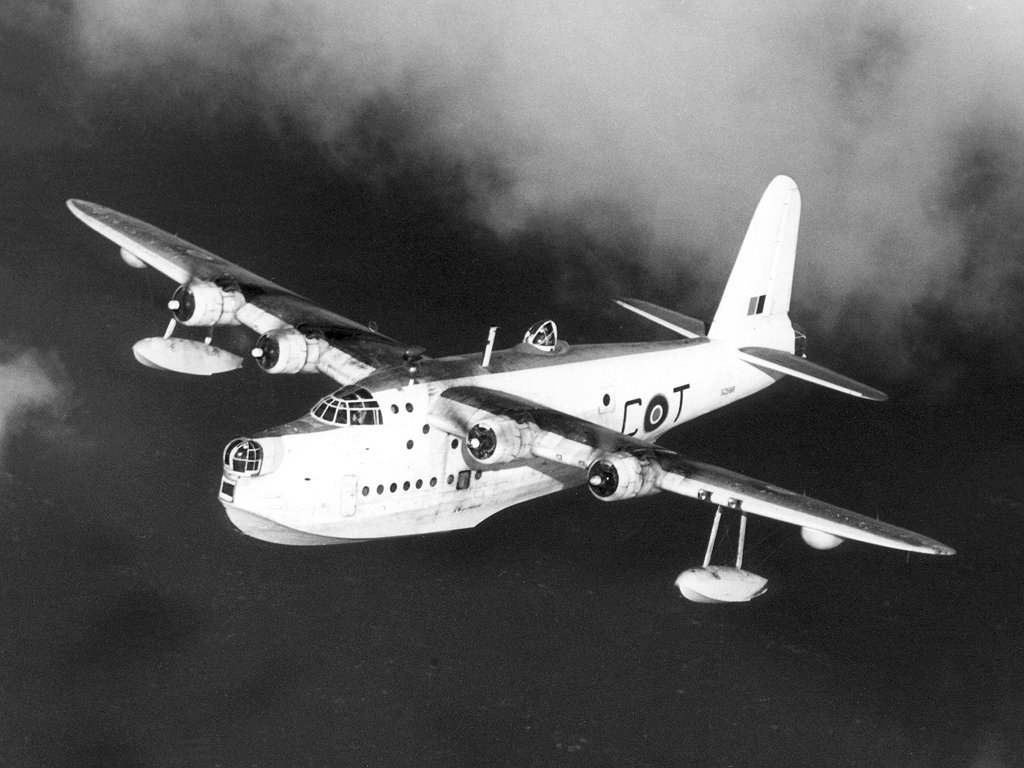

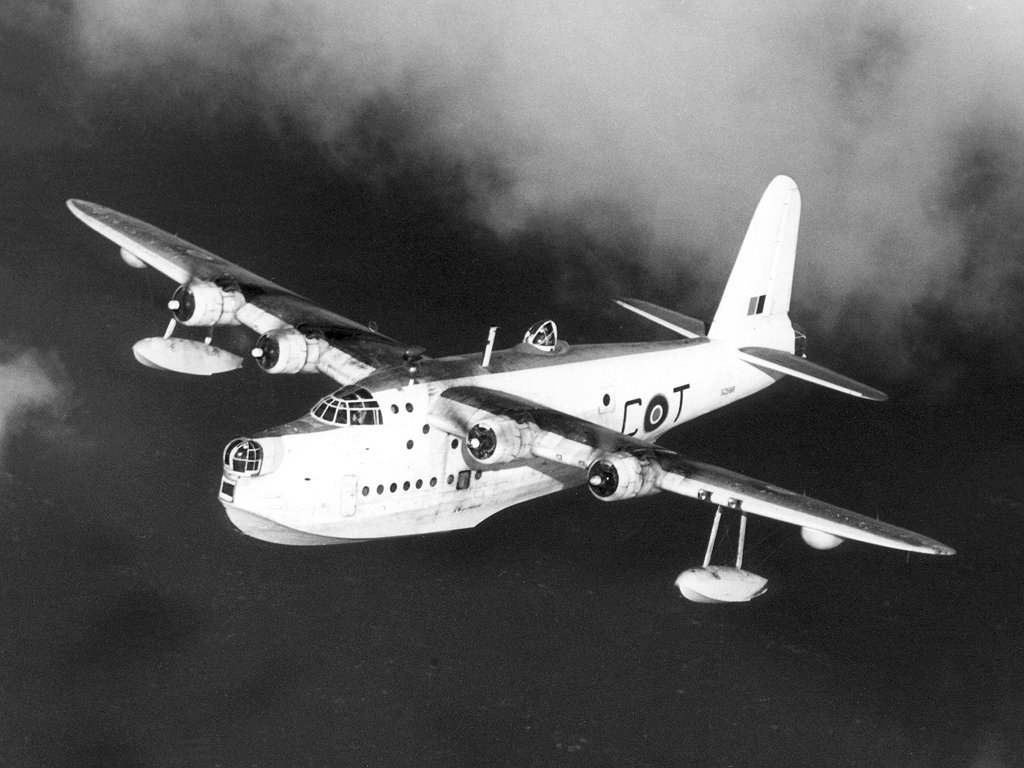

World War II

The military value of flying boats was well-recognized, and every country bordering on water operated them in a military capacity at the outbreak of the war. They were utilized in various tasks fromanti-submarine

An anti-submarine weapon (ASW) is any one of a number of devices that are intended to act against a submarine and its crew, to destroy (sink) the vessel or reduce its capability as a weapon of war. In its simplest sense, an anti-submarine weapon ...

patrol to air-sea rescue

Air-sea rescue (ASR or A/SR, also known as sea-air rescue), and aeronautical and maritime search and rescue (AMSAR) by the ICAO and International Maritime Organization, IMO, is the coordinated search and rescue (SAR) of the survivors of emergenc ...

and gunfire spotting for battleships. Aircraft such as the PBM Mariner

The Martin PBM Mariner is a twin-engine American patrol bomber flying boat of World War II and the early Cold War era. It was designed to complement the Consolidated PBY Catalina and PB2Y Coronado in service. A total of 1,366 PBMs were built ...

patrol bomber, PBY Catalina

The Consolidated Model 28, more commonly known as the PBY Catalina (U.S. Navy designation), is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft designed by Consolidated Aircraft in the 1930s and 1940s. In U.S. Army service, it was designated as the O ...

, Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland is a British flying boat Maritime patrol aircraft, patrol bomber, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF). The aircraft took its service name from the town (latterly, city) and port of ...

, and Grumman Goose recovered downed airmen and operated as scout aircraft over the vast distances of the Pacific Theater and Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

. They also sank numerous submarines and found enemy ships. In May 1941, the German battleship ''Bismarck'' was discovered by a PBY Catalina flying out of Castle Archdale Flying boat base, Lower Lough Erne, Northern Ireland.

The largest flying boat of the war was the Blohm & Voss BV 238

The Blohm & Voss BV 238 was a large six-engined flying boat designed and built by the German aircraft manufacturer Blohm & Voss. Developed during the Second World War, it was the heaviest aircraft ever built when it first flew in 1944, and was t ...

, which was also the heaviest plane to fly during World War II and the largest aircraft built and flown by any of the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

.

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies:

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies: British European Airways

British European Airways (BEA), formally British European Airways Corporation, was a British airline which existed from 1946 until 1974.

BEA operated to Europe, North Africa and the Middle East from airports around the United Kingdom. The ...

, British Overseas Airways Corporation

British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the United Kingdom, British state-owned national airline created in 1939 by the merger of Imperial Airways and British Airways Ltd. It continued operating overseas services throughout World War II ...

(BOAC), and British South American Airways (which merged with BOAC in 1949), with the change being made official on 1 April 1940. BOAC continued to operate flying-boat services from the (slightly) safer confines of Poole Harbour

Poole Harbour is a large natural harbour in Dorset, southern England, with the town of Poole on its shores. The harbour is a drowned valley ( ria) formed at the end of the last ice age and is the estuary of several rivers, the largest being th ...

during wartime, returning to Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

in 1947. When Italy entered the war in June 1940, the Mediterranean was closed to Allied planes and BOAC and Qantas

Qantas ( ), formally Qantas Airways Limited, is the flag carrier of Australia, and the largest airline by fleet size, international flights, and international destinations in Australia and List of largest airlines in Oceania, Oceania. A foundi ...

operated the Horseshoe Route between Durban and Sydney using Short Empire flying boats.

The Martin Company produced the prototype XPB2M Mars based on their PBM Mariner patrol bomber, with flight tests between 1941 and 1943. The Mars was converted by the Navy into a transport aircraft designated the XPB2M-1R. Satisfied with the performance, twenty of the modified JRM-1 Mars were ordered. The first, named ''Hawaii Mars'', was delivered in June 1945, but the Navy scaled back their order at the end of World War II, buying only the five aircraft which were then on the production line. The five Mars were completed, and the last delivered in 1947.Goebel, Greg. ''Vectorsite.'' Retrieved: May 20, 2012.

Post-War

After World War II, the use of flying boats rapidly declined for several reasons. The ability to land on water became less of an advantage owing to the considerable increase in the number and length of land-based runways during World War II. Further, as the speed and range of land-based aircraft increased, the commercial competitiveness of flying boats diminished; their design compromised aerodynamic efficiency and speed to accomplish the feat of waterborne takeoff and landing. Competing with new civilian jet aircraft like thede Havilland Comet

The de Havilland DH.106 Comet is the world's first commercial jet airliner. Developed and manufactured by de Havilland in the United Kingdom, the Comet 1 prototype first flew in 1949. It features an aerodynamically clean design with four ...

and Boeing 707

The Boeing 707 is an early American long-range Narrow-body aircraft, narrow-body airliner, the first jetliner developed and produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

Developed from the Boeing 367-80 prototype, the initial first flew on Decembe ...

proved impossible.

The Hughes H-4 Hercules

The Hughes H-4 Hercules (commonly known as the ''Spruce Goose''; Aircraft registration, registration NX37602) is a prototype strategic airlift flying boat designed and built by the Hughes Aircraft Company. Intended as a transatlantic flight t ...

, in development in the U.S. during the war, was even larger than the BV 238, but it did not fly until 1947. The "Spruce Goose", as the 180-ton H-4 was nicknamed, was the largest flying boat ever to fly. Carried out during Senate hearings into Hughes's use of government funds on its construction, the short hop of about a mile (1.6 km) at above the water by the "Flying Lumberyard" was claimed by Hughes as vindication of his efforts. Cutbacks in expenditure after the war and the disappearance of its intended mission as a transatlantic transport left it no purpose.

In 1944, the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

began development of a small jet-powered flying boat that it intended to use as an air defence

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface (Submarine#Armament, submarine-lau ...

aircraft optimised for the Pacific, where the relatively calm sea conditions around the many archipelagos made the use of seaplanes easier. By making the aircraft jet-powered, it was possible to design it with a hull rather than making it a floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

. The Saunders-Roe SR.A/1 prototype first flew in 1947 and was relatively successful in terms of its performance and handling. However, by the end of the war, carrier-based aircraft were becoming more sophisticated, and the need for the SR.A/1 evaporated.

During the Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, roa ...

(which lasted from June 1948 until August 1949), ten Sunderlands and two Hythes were used to transport goods from Finkenwerder on the Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

near Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

to isolated Berlin, landing on the Havelsee beside RAF Gatow until it iced over. The Sunderlands were particularly used for transporting salt, as their airframes were already protected against corrosion from seawater. Transporting salt in standard aircraft risked rapid and severe structural corrosion in the event of a spillage. In addition, three Aquila flying boats were used during the airlift. This is the only known operational use of flying boats within central Europe.

BOAC ceased flying boat services out of Southampton in November 1950.

Bucking the trend, in 1948, Aquila Airways was founded to serve destinations that were still inaccessible to land-based aircraft. This company operated Short S.25 and Short S.45 flying boats out of Southampton on routes to Madeira

Madeira ( ; ), officially the Autonomous Region of Madeira (), is an autonomous Regions of Portugal, autonomous region of Portugal. It is an archipelago situated in the North Atlantic Ocean, in the region of Macaronesia, just under north of ...

, Las Palmas

Las Palmas (, ; ), officially Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, is a Spanish city and capital of Gran Canaria, in the Canary Islands, in the Atlantic Ocean.

It is the capital city of the Canary Islands (jointly with Santa Cruz de Tenerife) and the m ...

, Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

, Mallorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest of the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, seventh largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.

The capital of the island, Palma, Majorca, Palma, i ...

, Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, Capri

Capri ( , ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. A popular resort destination since the time of the Roman Republic, its natural beauty ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Montreux

Montreux (, ; ; ) is a Municipalities of Switzerland, Swiss municipality and List of towns in Switzerland, town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Swiss Alps, Alps. It belongs to the Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut (district), Riviera-Pays ...

and Santa Margherita. From 1950 to 1957, Aquila also operated a service from Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

to Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

and Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

. The flying boats of Aquila Airways were also chartered for one-off trips, usually to deploy troops where scheduled services did not exist or where there were political considerations. The longest charter, in 1952, was from Southampton to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; ), commonly referred to as The Falklands, is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and from Cape Dub ...

. In 1953, the flying boats were chartered for troop-deployment trips to Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

and Lagos

Lagos ( ; ), or Lagos City, is a large metropolitan city in southwestern Nigeria. With an upper population estimated above 21 million dwellers, it is the largest city in Nigeria, the most populous urban area on the African continent, and on ...

, and there was a special trip from Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually shortened to Hull, is a historic maritime city and unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Est ...

to Helsinki

Helsinki () is the Capital city, capital and most populous List of cities and towns in Finland, city in Finland. It is on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and is the seat of southern Finland's Uusimaa region. About people live in the municipali ...

to relocate a ship's crew. The airline ceased operations on 30 September 1958.

The technically advanced Saunders-Roe Princess first flew in 1952 and later received a certificate of airworthiness

A standard certificate of airworthiness is a permit for commercial passenger or cargo operation, issued for an aircraft by the civil aviation authority in the state/nation in which the aircraft is registered. For other aircraft such as crop-spray ...

. Despite being the pinnacle of flying-boat development, none were sold, though Aquila Airways reportedly attempted to buy them. Of the three Princesses

Princess is a title used by a female member of a regnant monarch's family or by a female ruler of a principality. The male equivalent is a prince (from Latin '' princeps'', meaning principal citizen). Most often, the term has been used for ...

that were built, two never flew, and all were scrapped in 1967. In the late 1940s, Saunders-Roe also produced the jet-powered SR.A/1 flying-boat fighter, which did not progress beyond flying prototypes.

The U.S. Navy continued to operate flying boats (notably the Martin P5M Marlin

The Martin P5M Marlin (P-5 Marlin after 1962), built by the Glenn L. Martin Company of Middle River, Maryland, is a twin piston-engined flying boat that entered service in 1951, and served into the late 1960s with the United States Navy perform ...

) until the early 1970s. The Navy even experimented with the Martin Seamaster jet-powered seaplane bomber, as well as the Convair F2Y Sea Dart supersonic interceptor.

The U.S. Coast Guard operated HU-16 Albatross (affectionately known as the 'goat') well into the 1980s, retiring them as the airframes clocked out their flying 11 thousand flying hours. About twenty were still in service in the 1970s, and the last operation flight was in 1983. The aircraft was very popular with the Coast Guard due to its unique capabilities compared to other types, and was noted for its versatility, range, and ability to land on water which was especially useful for water rescues.

Ansett Australia

Ansett Australia, originally Ansett Airways, was a major Australian airline group based in Melbourne, Victoria. The company operated domestically within Australia, and from the 1990s, to destinations in Asia. Following 65 years of operation, ...

operated a flying-boat service from Rose Bay to Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, part of the Australian state of New South Wales. It lies directly east of mainland Port ...

until 1974, using Short Sandringhams.

On 18 December 1990, Pilot Tom Casey completed the first round-the-world flight in a floatplane with only water landings using a Cessna 206 named Liberty II.

Uses and operation

Many modern civilian aircraft have a floatplane variant, usually as utility transports to lakes and other remote areas. Most of these are offered as third-party modifications under a supplemental type certificate (STC), although there are several aircraft manufacturers that build floatplanes from scratch, and a few that continue to build

Many modern civilian aircraft have a floatplane variant, usually as utility transports to lakes and other remote areas. Most of these are offered as third-party modifications under a supplemental type certificate (STC), although there are several aircraft manufacturers that build floatplanes from scratch, and a few that continue to build flying boats

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull (watercraft), hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for b ...

. Some older flying boats remain in service for firefighting duty, as well as the Canadair CL-415

The Canadair CL-415 (Super Scooper, later Bombardier 415) and the De Havilland Canada DHC-515 are a series of amphibious aircraft built originally by Canadair and subsequently by Bombardier and De Havilland Canada. The CL-415 is based on the ...

which remains in production as of 2022, and Chalk's Ocean Airways operated a fleet of Grumman Mallards in passenger service until service was suspended after a crash on December 19, 2005, which was linked to maintenance, not to design of the aircraft. Purely water-based seaplanes have largely been supplanted by amphibious aircraft.

Seaplanes can only take off and land on water with little or no wave

In physics, mathematics, engineering, and related fields, a wave is a propagating dynamic disturbance (change from List of types of equilibrium, equilibrium) of one or more quantities. ''Periodic waves'' oscillate repeatedly about an equilibrium ...

action and, like other aircraft, have trouble in extreme weather. The size of waves a given design can withstand depends on, among other factors, the aircraft's size, hull or float design, and its weight, all making for a much more unstable aircraft, limiting actual operational days.

Flying boats can typically handle rougher water and are generally more stable than floatplanes while on the water.

Seaplanes are also used in remote areas such as the Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

n and Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

wilderness, especially in areas with a large number of lake

A lake is often a naturally occurring, relatively large and fixed body of water on or near the Earth's surface. It is localized in a basin or interconnected basins surrounded by dry land. Lakes lie completely on land and are separate from ...

s convenient for takeoff and landing. They may operate on a charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the ...

basis, provide scheduled service, or be operated by residents of the area for personal use. There are seaplane operators that offer services between islands such as in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

or the Maldives

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives, and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in South Asia located in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, abou ...

. Usually these are converted from reliable commercial models, and fitted for floats.

One floatplane conversion under consideration in the 2020s is a floatplane version of the C-130

The Lockheed C-130 Hercules is an American four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft designed and built by Lockheed Corporation, Lockheed (now Lockheed Martin). Capable of using unprepared runways for takeoffs and landings, the C-130 w ...

for special military applications.

See also

*List of flying boats and floatplanes

The following is a list of seaplanes, which includes floatplanes and flying boats. A seaplane is any airplane that has the capability of landing and taking off from water, while an amphibian is a seaplane which can also operate from land. (They d ...

* Ground effect vehicle

A ground-effect vehicle (GEV), also called a wing-in-ground-effect (WIGE or WIG), ground-effect craft/machine (GEM), wingship, flarecraft, surface effect vehicle or ekranoplan (), is a vehicle that is able to move over the surface by gaining su ...

* IAR 111

The IAR-111 Excelsior was a supersonic mothership project, designed by ARCA Space Corporation, intended to transport a rocket payload up to and for developing space tourism related technologies. The aircraft was supposed to be constructed almost ...

* Navalised aircraft

* Aerosub

* Observation seaplane

Observation seaplanes are military aircraft with flotation devices allowing them to land on and take off from water. Their primary purpose was to observe and report enemy movements or to spot the fall of shot from naval artillery, but some were a ...

* Seaplane tender

A seaplane tender is a boat or ship that supports the operation of seaplanes. Some of these vessels, known as seaplane carriers, could not only carry seaplanes but also provided all the facilities needed for their operation; these ships are rega ...

References

External links

* {{Authority control