Sea Adventure Films on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the

The sea is the interconnected system of all the Earth's oceanic waters, including the

The sea is the interconnected system of all the Earth's oceanic waters, including the

Lesson 7: The Water Cycle

" in ''Ocean Explorer''. The scientific study of

Drinking Seawater Can Be Deadly to Humans

".

Technical Summary

. I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, and New York, pp. 33–144.

. USGS. By Richard Z. Poore, Richard S. Williams, Jr., and Christopher Tracey. For at least the last 100 years, sea level has been rising at an average rate of about per year. Most of this rise can be attributed to an increase in the temperature of the sea due to

''Essentials of Oceanography''

. 6th ed. pp. 204 ff. Brooks/Cole, Belmont. . Most waves are less than high and it is not unusual for strong storms to double or triple that height;

A tsunami is an unusual form of wave caused by an infrequent powerful event such as an underwater earthquake or landslide, a meteorite impact, a volcanic eruption or a collapse of land into the sea. These events can temporarily lift or lower the surface of the sea in the affected area, usually by a few feet. The potential energy of the displaced seawater is turned into kinetic energy, creating a shallow wave, a tsunami, radiating outwards at a velocity proportional to the square root of the depth of the water and which therefore travels much faster in the open ocean than on a continental shelf. In the deep open sea, tsunamis have wavelengths of around , travel at speeds of over and usually have a height of less than three feet, so they often pass unnoticed at this stage. In contrast, ocean surface waves caused by winds have wavelengths of a few hundred feet, travel at up to and are up to high.

As a tsunami moves into shallower water its speed decreases, its wavelength shortens and its amplitude increases enormously, behaving in the same way as a wind-generated wave in shallow water but on a vastly greater scale. Either the trough or the crest of a tsunami can arrive at the coast first. In the former case, the sea draws back and leaves subtidal areas close to the shore exposed which provides a useful warning for people on land. When the crest arrives, it does not usually break but rushes inland, flooding all in its path. Much of the destruction may be caused by the flood water draining back into the sea after the tsunami has struck, dragging debris and people with it. Often several tsunami are caused by a single geological event and arrive at intervals of between eight minutes and two hours. The first wave to arrive on shore may not be the biggest or most destructive.

A tsunami is an unusual form of wave caused by an infrequent powerful event such as an underwater earthquake or landslide, a meteorite impact, a volcanic eruption or a collapse of land into the sea. These events can temporarily lift or lower the surface of the sea in the affected area, usually by a few feet. The potential energy of the displaced seawater is turned into kinetic energy, creating a shallow wave, a tsunami, radiating outwards at a velocity proportional to the square root of the depth of the water and which therefore travels much faster in the open ocean than on a continental shelf. In the deep open sea, tsunamis have wavelengths of around , travel at speeds of over and usually have a height of less than three feet, so they often pass unnoticed at this stage. In contrast, ocean surface waves caused by winds have wavelengths of a few hundred feet, travel at up to and are up to high.

As a tsunami moves into shallower water its speed decreases, its wavelength shortens and its amplitude increases enormously, behaving in the same way as a wind-generated wave in shallow water but on a vastly greater scale. Either the trough or the crest of a tsunami can arrive at the coast first. In the former case, the sea draws back and leaves subtidal areas close to the shore exposed which provides a useful warning for people on land. When the crest arrives, it does not usually break but rushes inland, flooding all in its path. Much of the destruction may be caused by the flood water draining back into the sea after the tsunami has struck, dragging debris and people with it. Often several tsunami are caused by a single geological event and arrive at intervals of between eight minutes and two hours. The first wave to arrive on shore may not be the biggest or most destructive.

Surface currents only affect the top few hundred metres of the sea, but there are also large-scale flows in the ocean depths caused by the movement of deep water masses. A main deep ocean current flows through all the world's oceans and is known as the

Surface currents only affect the top few hundred metres of the sea, but there are also large-scale flows in the ocean depths caused by the movement of deep water masses. A main deep ocean current flows through all the world's oceans and is known as the

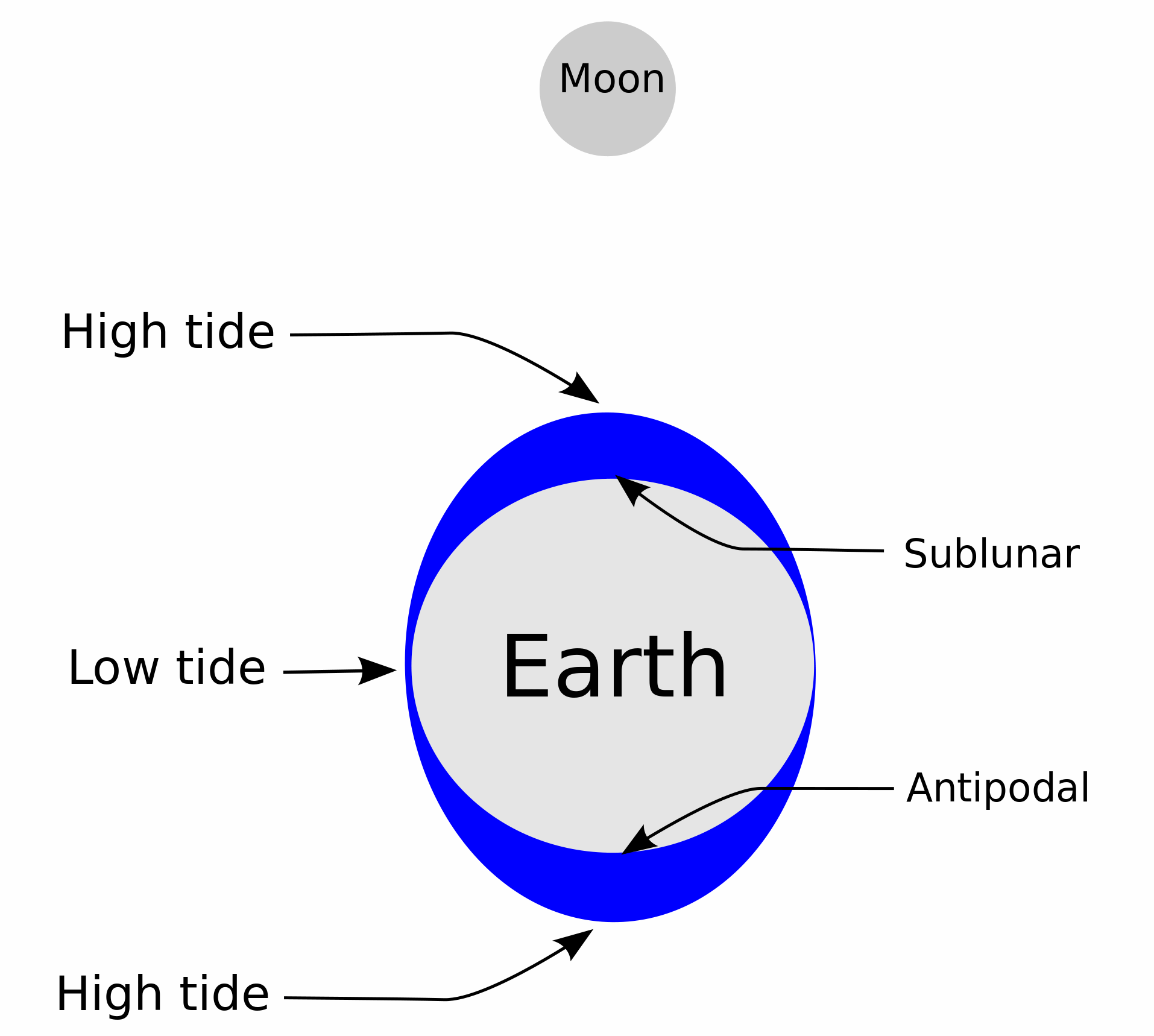

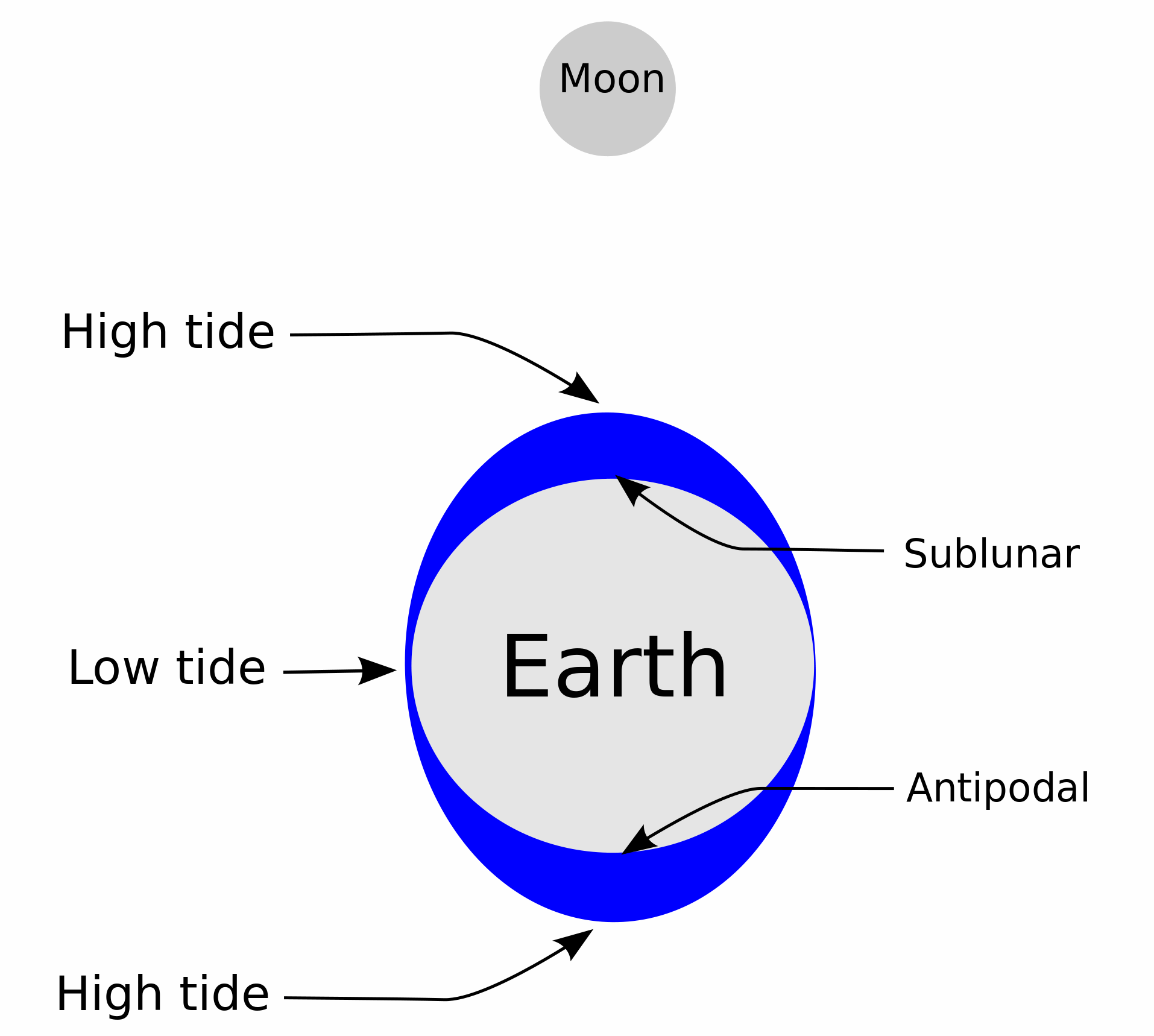

Tides are the regular rise and fall in water level experienced by seas and oceans in response to the gravitational influences of the Moon and the Sun, and the effects of the Earth's rotation. During each tidal cycle, at any given place the water rises to a maximum height known as "high tide" before ebbing away again to the minimum "low tide" level. As the water recedes, it uncovers more and more of the

Tides are the regular rise and fall in water level experienced by seas and oceans in response to the gravitational influences of the Moon and the Sun, and the effects of the Earth's rotation. During each tidal cycle, at any given place the water rises to a maximum height known as "high tide" before ebbing away again to the minimum "low tide" level. As the water recedes, it uncovers more and more of the

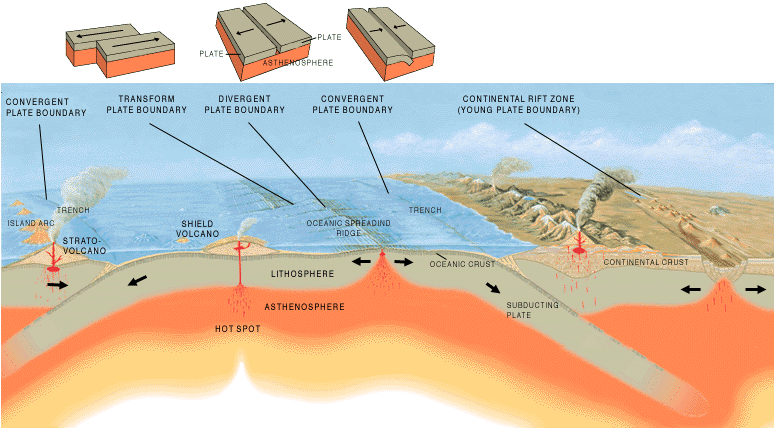

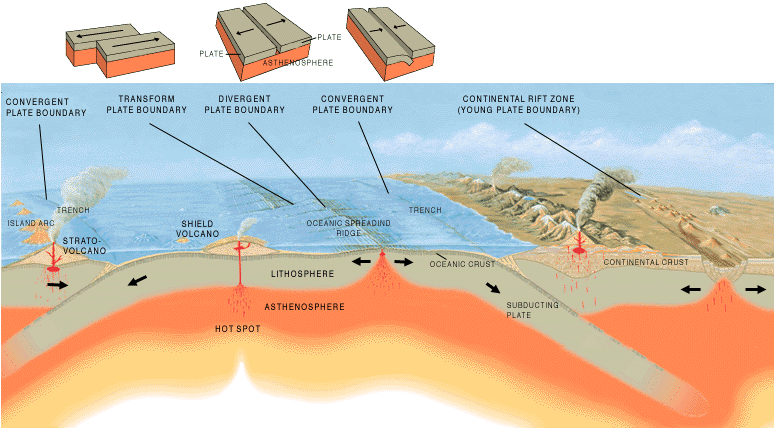

The Earth is composed of a magnetic central core, a mostly liquid mantle and a hard rigid outer shell (or

The Earth is composed of a magnetic central core, a mostly liquid mantle and a hard rigid outer shell (or

The oceans are home to a diverse collection of life forms that use it as a habitat. Since sunlight illuminates only the upper layers, the major part of the ocean exists in permanent darkness. As the different depth and temperature zones each provide habitat for a unique set of species, the marine environment as a whole encompasses an immense diversity of life. Marine habitats range from surface water to the deepest

The oceans are home to a diverse collection of life forms that use it as a habitat. Since sunlight illuminates only the upper layers, the major part of the ocean exists in permanent darkness. As the different depth and temperature zones each provide habitat for a unique set of species, the marine environment as a whole encompasses an immense diversity of life. Marine habitats range from surface water to the deepest

Humans have Navigation, travelled the seas since they first built sea-going craft. Ubaid period, Mesopotamians were using bitumen#ancient times, bitumen to caulking, caulk their reed boat#History, reed boats and, a little later, masted sails.Carter, Robert (2012). ''A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East''. Ch. 19: "Watercraft", pp. 347 ff. Wiley-Blackwell. . By c. 3000 BC, Austronesian people, Austronesians on Taiwan had begun spreading into maritime Southeast Asia. Subsequently, the Austronesian "Lapita" peoples displayed great feats of navigation, reaching out from the Bismarck Archipelago to as far away as Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa. Their descendants Polynesian navigation, continued to travel thousands of miles between tiny islands on outrigger canoe#History, outrigger canoes, and in the process they found many new islands, including Hawaii, Easter Island (Rapa Nui), and New Zealand.

The Ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians explored the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and Red Sea with the Egyptian Hannu reaching the Arabian Peninsula and the African Coast around 2750 BC. In the first millennium BC, Phoenicians and Greeks established colonies throughout the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Around 500 BC, the Carthage, Carthaginian navigator Hanno the Navigator, Hanno left a detailed periplus of an Atlantic journey that reached at least Senegal and possibly Mount Cameroon. In the Dark Ages (historiography), early Mediaeval period, the Vikings crossed the North Atlantic and even reached the northeastern fringes of North America. Novgorod Republic, Novgorodians had also been sailing the White Sea since the 13th century or before. Meanwhile, the seas along the eastern and southern Asian coast were used by Arab and Chinese traders. The Chinese Ming Dynasty had a fleet of 317 ships with 37,000 men under Zheng He in the early fifteenth century, sailing the Indian and Pacific Oceans. In the late fifteenth century, Western European mariners started making longer voyages of exploration in search of trade. Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487 and Vasco da Gama reached India via the Cape in 1498. Christopher Columbus sailed from Cadiz in 1492, attempting to reach the eastern lands of India and Japan by the novel means of travelling westwards. He made landfall instead on an island in the Caribbean Sea and a few years later, the Venetian navigator John Cabot reached Newfoundland. The Italian Amerigo Vespucci, after whom America was named, explored the South American coastline in voyages made between 1497 and 1502, discovering the mouth of the Amazon River. In 1519 the Portugal, Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan led the Spanish Timeline of the Magellan–Elcano circumnavigation, Magellan-Elcano expedition which would be the first to sail around the world.

Humans have Navigation, travelled the seas since they first built sea-going craft. Ubaid period, Mesopotamians were using bitumen#ancient times, bitumen to caulking, caulk their reed boat#History, reed boats and, a little later, masted sails.Carter, Robert (2012). ''A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East''. Ch. 19: "Watercraft", pp. 347 ff. Wiley-Blackwell. . By c. 3000 BC, Austronesian people, Austronesians on Taiwan had begun spreading into maritime Southeast Asia. Subsequently, the Austronesian "Lapita" peoples displayed great feats of navigation, reaching out from the Bismarck Archipelago to as far away as Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa. Their descendants Polynesian navigation, continued to travel thousands of miles between tiny islands on outrigger canoe#History, outrigger canoes, and in the process they found many new islands, including Hawaii, Easter Island (Rapa Nui), and New Zealand.

The Ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians explored the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and Red Sea with the Egyptian Hannu reaching the Arabian Peninsula and the African Coast around 2750 BC. In the first millennium BC, Phoenicians and Greeks established colonies throughout the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Around 500 BC, the Carthage, Carthaginian navigator Hanno the Navigator, Hanno left a detailed periplus of an Atlantic journey that reached at least Senegal and possibly Mount Cameroon. In the Dark Ages (historiography), early Mediaeval period, the Vikings crossed the North Atlantic and even reached the northeastern fringes of North America. Novgorod Republic, Novgorodians had also been sailing the White Sea since the 13th century or before. Meanwhile, the seas along the eastern and southern Asian coast were used by Arab and Chinese traders. The Chinese Ming Dynasty had a fleet of 317 ships with 37,000 men under Zheng He in the early fifteenth century, sailing the Indian and Pacific Oceans. In the late fifteenth century, Western European mariners started making longer voyages of exploration in search of trade. Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487 and Vasco da Gama reached India via the Cape in 1498. Christopher Columbus sailed from Cadiz in 1492, attempting to reach the eastern lands of India and Japan by the novel means of travelling westwards. He made landfall instead on an island in the Caribbean Sea and a few years later, the Venetian navigator John Cabot reached Newfoundland. The Italian Amerigo Vespucci, after whom America was named, explored the South American coastline in voyages made between 1497 and 1502, discovering the mouth of the Amazon River. In 1519 the Portugal, Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan led the Spanish Timeline of the Magellan–Elcano circumnavigation, Magellan-Elcano expedition which would be the first to sail around the world.

As for the history of navigational instrument, a compass was first used by the ancient Greeks and Chinese to show where north lies and the direction in which the ship is heading. The latitude (an angle which ranges from 0° at the equator to 90° at the poles) was determined by measuring the angle between the Sun, Moon or a specific star and the horizon by the use of an astrolabe, Jacob's staff or Sextant (astronomical), sextant. The longitude (a line on the globe joining the two poles) could only be calculated with an accurate Marine chronometer, chronometer to show the exact time difference between the ship and a fixed point such as the Prime meridian (Greenwich), Greenwich Meridian. In 1759, John Harrison, a clockmaker, designed such an instrument and James Cook used it in his voyages of exploration. Nowadays, the Global Positioning System (GPS) using over thirty satellites enables accurate navigation worldwide.

With regards to maps that are vital for navigation, in the second century, Ptolemy mapped the whole known world from the "Fortunatae Insulae", Cape Verde or Canary Islands, eastward to the Gulf of Thailand. This map was used in 1492 when Christopher Columbus set out on his voyages of discovery. Subsequently, Gerardus Mercator made a practical map of the world in 1538, his map projection conveniently making rhumb lines straight. By the eighteenth century better maps had been made and part of the objective of James Cook on his voyages was to further map the ocean. Scientific study has continued with the depth recordings of the ''USS Tuscarora (1861), Tuscarora'', the oceanic research of the Challenger expedition, Challenger voyages (1872–1876), the work of the Scandinavian seamen Roald Amundsen and Fridtjof Nansen, the Michael Sars expedition in 1910, the German Meteor expedition of 1925, the Antarctic survey work of ''RRS Discovery II, Discovery II'' in 1932, and others since. Furthermore, in 1921, the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) was set up, and it constitutes the world authority on Hydrography, hydrographic surveying and nautical charting. A fourth edition draft was published in 1986 but so far several naming disputes (such as the one over the Sea of Japan naming dispute, Sea of Japan) have prevented its ratification.

As for the history of navigational instrument, a compass was first used by the ancient Greeks and Chinese to show where north lies and the direction in which the ship is heading. The latitude (an angle which ranges from 0° at the equator to 90° at the poles) was determined by measuring the angle between the Sun, Moon or a specific star and the horizon by the use of an astrolabe, Jacob's staff or Sextant (astronomical), sextant. The longitude (a line on the globe joining the two poles) could only be calculated with an accurate Marine chronometer, chronometer to show the exact time difference between the ship and a fixed point such as the Prime meridian (Greenwich), Greenwich Meridian. In 1759, John Harrison, a clockmaker, designed such an instrument and James Cook used it in his voyages of exploration. Nowadays, the Global Positioning System (GPS) using over thirty satellites enables accurate navigation worldwide.

With regards to maps that are vital for navigation, in the second century, Ptolemy mapped the whole known world from the "Fortunatae Insulae", Cape Verde or Canary Islands, eastward to the Gulf of Thailand. This map was used in 1492 when Christopher Columbus set out on his voyages of discovery. Subsequently, Gerardus Mercator made a practical map of the world in 1538, his map projection conveniently making rhumb lines straight. By the eighteenth century better maps had been made and part of the objective of James Cook on his voyages was to further map the ocean. Scientific study has continued with the depth recordings of the ''USS Tuscarora (1861), Tuscarora'', the oceanic research of the Challenger expedition, Challenger voyages (1872–1876), the work of the Scandinavian seamen Roald Amundsen and Fridtjof Nansen, the Michael Sars expedition in 1910, the German Meteor expedition of 1925, the Antarctic survey work of ''RRS Discovery II, Discovery II'' in 1932, and others since. Furthermore, in 1921, the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) was set up, and it constitutes the world authority on Hydrography, hydrographic surveying and nautical charting. A fourth edition draft was published in 1986 but so far several naming disputes (such as the one over the Sea of Japan naming dispute, Sea of Japan) have prevented its ratification.

Control of the sea is important to the security of a maritime nation, and the naval blockade of a port can be used to cut off food and supplies in time of war. Battles have been fought on the sea for more than 3,000 years. In about 1210 B.C., Suppiluliuma II, the king of the Hittites, defeated and burned a fleet from Alashiya (modern Cyprus). In the decisive 480 B.C. Battle of Salamis, the Greek general Themistocles trapped the far larger fleet of the Persian king Xerxes II of Persia, Xerxes in a narrow channel and attacked vigorously, destroying 200 Persian ships for the loss of 40 Greek vessels. At the end of the Age of Sail, the British Royal Navy, led by Horatio Nelson, broke the power of the combined French and Spanish fleets at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar.

With steam and the industrial production of steel plate came greatly increased firepower in the shape of the dreadnought battleships armed with long-range guns. In 1905, the Japanese fleet decisively defeated the Russian fleet, which had travelled over , at the Battle of Tsushima. Dreadnoughts fought inconclusively in the First World War at the 1916 Battle of Jutland between the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet. In the Second World War, the British victory at the 1940 Battle of Taranto showed that naval air power was sufficient to overcome the largest warships, foreshadowing the decisive sea-battles of the Pacific War including the Battles of the Battle of the Coral Sea, Coral Sea, Battle of Midway, Midway, Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Philippine Sea, and the climactic Battle of Leyte Gulf, in all of which the dominant ships were aircraft carriers.

Submarines became important in naval warfare in World War I, when German submarines, known as U-boats, sank nearly 5,000 Allied merchant ships, including the RMS Lusitania, which helped to bring the United States into the war. In World War II, almost 3,000 Allied ships were sunk by U-boats attempting to block the flow of supplies to Britain, but the Allies broke the blockade in the Battle of the Atlantic, which lasted the whole length of the war, sinking 783 U-boats. Since 1960, several nations have maintained fleets of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, vessels equipped to launch ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads from under the sea. Some of these are kept permanently on patrol.

Control of the sea is important to the security of a maritime nation, and the naval blockade of a port can be used to cut off food and supplies in time of war. Battles have been fought on the sea for more than 3,000 years. In about 1210 B.C., Suppiluliuma II, the king of the Hittites, defeated and burned a fleet from Alashiya (modern Cyprus). In the decisive 480 B.C. Battle of Salamis, the Greek general Themistocles trapped the far larger fleet of the Persian king Xerxes II of Persia, Xerxes in a narrow channel and attacked vigorously, destroying 200 Persian ships for the loss of 40 Greek vessels. At the end of the Age of Sail, the British Royal Navy, led by Horatio Nelson, broke the power of the combined French and Spanish fleets at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar.

With steam and the industrial production of steel plate came greatly increased firepower in the shape of the dreadnought battleships armed with long-range guns. In 1905, the Japanese fleet decisively defeated the Russian fleet, which had travelled over , at the Battle of Tsushima. Dreadnoughts fought inconclusively in the First World War at the 1916 Battle of Jutland between the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet. In the Second World War, the British victory at the 1940 Battle of Taranto showed that naval air power was sufficient to overcome the largest warships, foreshadowing the decisive sea-battles of the Pacific War including the Battles of the Battle of the Coral Sea, Coral Sea, Battle of Midway, Midway, Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Philippine Sea, and the climactic Battle of Leyte Gulf, in all of which the dominant ships were aircraft carriers.

Submarines became important in naval warfare in World War I, when German submarines, known as U-boats, sank nearly 5,000 Allied merchant ships, including the RMS Lusitania, which helped to bring the United States into the war. In World War II, almost 3,000 Allied ships were sunk by U-boats attempting to block the flow of supplies to Britain, but the Allies broke the blockade in the Battle of the Atlantic, which lasted the whole length of the war, sinking 783 U-boats. Since 1960, several nations have maintained fleets of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, vessels equipped to launch ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads from under the sea. Some of these are kept permanently on patrol.

Maritime trade has existed for millennia. The Ptolemaic dynasty had developed trade with India using the Red Sea ports, and in the first millennium BC, the Arabs, Phoenicians, Israelites and Indians traded in luxury goods such as spices, gold, and precious stones. The Phoenicians were noted sea traders and under the Greeks and Romans, commerce continued to thrive. With the collapse of the Roman Empire, European trade dwindled but it continued to flourish among the kingdoms of Africa, the Middle East, India, China and southeastern Asia. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, over a period of 400 years, about 12–13 million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic to be sold as slaves in the Americas as part of the Atlantic slave trade.

Large quantities of goods are transported by sea, especially across the Atlantic and around the Pacific Rim. A major trade route passes through the Pillars of Hercules, across the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean and through the Straits of Malacca; much trade also passes through the English Channel. Shipping lanes are the routes on the open sea used by cargo vessels, traditionally making use of trade winds and currents. Over 60 percent of the world's container traffic is conveyed on the top twenty trade routes. Increased melting of Arctic ice since 2007 enables ships to travel the Northwest Passage for some weeks in summertime, avoiding the longer routes via the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal.

Shipping is supplemented by air freight, a more expensive process mostly used for particularly valuable or perishable cargoes. Seaborne trade carries more than US$4 trillion worth of goods each year. Bulk cargo in the form of liquids, powder or particles are carried loose in the Hold (ship), holds of bulk carriers and include Petroleum, crude oil, grain, coal, ore, Scrap, scrap metal, sand and gravel. Other cargo, such as manufactured goods, is usually transported within Shipping container, standard-sized, lockable containers, loaded on purpose-built container ships at Container port, dedicated terminals. Before the rise of containerization in the 1960s, these goods were loaded, transported and unloaded piecemeal as Breakbulk cargo, break-bulk cargo. Containerization greatly increased the efficiency and decreased the cost of moving goods by sea, and was a major factor leading to the rise of globalization and exponential increases in international trade in the mid-to-late 20th century.

Maritime trade has existed for millennia. The Ptolemaic dynasty had developed trade with India using the Red Sea ports, and in the first millennium BC, the Arabs, Phoenicians, Israelites and Indians traded in luxury goods such as spices, gold, and precious stones. The Phoenicians were noted sea traders and under the Greeks and Romans, commerce continued to thrive. With the collapse of the Roman Empire, European trade dwindled but it continued to flourish among the kingdoms of Africa, the Middle East, India, China and southeastern Asia. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, over a period of 400 years, about 12–13 million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic to be sold as slaves in the Americas as part of the Atlantic slave trade.

Large quantities of goods are transported by sea, especially across the Atlantic and around the Pacific Rim. A major trade route passes through the Pillars of Hercules, across the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean and through the Straits of Malacca; much trade also passes through the English Channel. Shipping lanes are the routes on the open sea used by cargo vessels, traditionally making use of trade winds and currents. Over 60 percent of the world's container traffic is conveyed on the top twenty trade routes. Increased melting of Arctic ice since 2007 enables ships to travel the Northwest Passage for some weeks in summertime, avoiding the longer routes via the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal.

Shipping is supplemented by air freight, a more expensive process mostly used for particularly valuable or perishable cargoes. Seaborne trade carries more than US$4 trillion worth of goods each year. Bulk cargo in the form of liquids, powder or particles are carried loose in the Hold (ship), holds of bulk carriers and include Petroleum, crude oil, grain, coal, ore, Scrap, scrap metal, sand and gravel. Other cargo, such as manufactured goods, is usually transported within Shipping container, standard-sized, lockable containers, loaded on purpose-built container ships at Container port, dedicated terminals. Before the rise of containerization in the 1960s, these goods were loaded, transported and unloaded piecemeal as Breakbulk cargo, break-bulk cargo. Containerization greatly increased the efficiency and decreased the cost of moving goods by sea, and was a major factor leading to the rise of globalization and exponential increases in international trade in the mid-to-late 20th century.

Tidal power uses generators to produce electricity from tidal flows, sometimes by using a dam to store and then release seawater. The Rance barrage, long, near St Malo in Brittany opened in 1967; it generates about 0.5 GW, but it has been followed by few similar schemes.

The large and highly variable energy of waves gives them enormous destructive capability, making affordable and reliable wave machines problematic to develop. A small 2 MW commercial wave power plant, "Osprey", was built in Northern Scotland in 1995 about offshore. It was soon damaged by waves, then destroyed by a storm.

Offshore wind power is captured by wind turbines placed out at sea; it has the advantage that wind speeds are higher than on land, though wind farms are more costly to construct offshore. The first offshore wind farm was installed in Denmark in 1991, and the installed capacity of worldwide offshore wind farms reached 34 GW in 2020, mainly situated in Europe.

Tidal power uses generators to produce electricity from tidal flows, sometimes by using a dam to store and then release seawater. The Rance barrage, long, near St Malo in Brittany opened in 1967; it generates about 0.5 GW, but it has been followed by few similar schemes.

The large and highly variable energy of waves gives them enormous destructive capability, making affordable and reliable wave machines problematic to develop. A small 2 MW commercial wave power plant, "Osprey", was built in Northern Scotland in 1995 about offshore. It was soon damaged by waves, then destroyed by a storm.

Offshore wind power is captured by wind turbines placed out at sea; it has the advantage that wind speeds are higher than on land, though wind farms are more costly to construct offshore. The first offshore wind farm was installed in Denmark in 1991, and the installed capacity of worldwide offshore wind farms reached 34 GW in 2020, mainly situated in Europe.

Seafloor massive sulfide deposits, Seafloor massive sulphide deposits are potential sources of silver, gold, copper, lead and zinc and trace metals since their discovery in the 1960s. They form when Geothermal gradient, geothermally heated water is emitted from deep sea hydrothermal vents known as "black smokers". The ores are of high quality but prohibitively costly to extract.

There are large deposits of petroleum and natural gas, in rocks beneath the seabed. Oil platform, Offshore platforms and drilling rigs Offshore drilling, extract the oil or gas and store it for transport to land. Offshore oil and gas production can be difficult due to the remote, harsh environment. Drilling for oil in the sea has environmental impacts. Animals may be disorientated by seismic waves used to locate deposits, and there is debate as to whether this causes the Beached whale, beaching of whales. Toxic substances such as mercury, lead and arsenic may be released. The infrastructure may cause damage, and oil may be spilt.

Large quantities of methane clathrate exist on the seabed and in ocean sediment, of interest as a potential energy source. Also on the seabed are manganese nodules formed of layers of iron, manganese and other hydroxides around a core. In the Pacific, these may cover up to 30 percent of the deep ocean floor. The minerals precipitate from seawater and grow very slowly. Their commercial extraction for nickel was investigated in the 1970s but abandoned in favour of more convenient sources. In suitable locations, diamonds are gathered from the seafloor using suction hoses to bring gravel ashore. In deeper waters, mobile seafloor crawlers are used and the deposits are pumped to a vessel above. In Namibia, more diamonds are now collected from marine sources than by conventional methods on land.

Seafloor massive sulfide deposits, Seafloor massive sulphide deposits are potential sources of silver, gold, copper, lead and zinc and trace metals since their discovery in the 1960s. They form when Geothermal gradient, geothermally heated water is emitted from deep sea hydrothermal vents known as "black smokers". The ores are of high quality but prohibitively costly to extract.

There are large deposits of petroleum and natural gas, in rocks beneath the seabed. Oil platform, Offshore platforms and drilling rigs Offshore drilling, extract the oil or gas and store it for transport to land. Offshore oil and gas production can be difficult due to the remote, harsh environment. Drilling for oil in the sea has environmental impacts. Animals may be disorientated by seismic waves used to locate deposits, and there is debate as to whether this causes the Beached whale, beaching of whales. Toxic substances such as mercury, lead and arsenic may be released. The infrastructure may cause damage, and oil may be spilt.

Large quantities of methane clathrate exist on the seabed and in ocean sediment, of interest as a potential energy source. Also on the seabed are manganese nodules formed of layers of iron, manganese and other hydroxides around a core. In the Pacific, these may cover up to 30 percent of the deep ocean floor. The minerals precipitate from seawater and grow very slowly. Their commercial extraction for nickel was investigated in the 1970s but abandoned in favour of more convenient sources. In suitable locations, diamonds are gathered from the seafloor using suction hoses to bring gravel ashore. In deeper waters, mobile seafloor crawlers are used and the deposits are pumped to a vessel above. In Namibia, more diamonds are now collected from marine sources than by conventional methods on land.

The sea holds large quantities of valuable dissolved minerals. The most important, Sea salt, Salt for table and industrial use has been harvested by solar evaporation from shallow ponds since prehistoric times. Bromine, accumulated after being leached from the land, is economically recovered from the Dead Sea, where it occurs at 55,000 parts per million (ppm).

The sea holds large quantities of valuable dissolved minerals. The most important, Sea salt, Salt for table and industrial use has been harvested by solar evaporation from shallow ponds since prehistoric times. Bromine, accumulated after being leached from the land, is economically recovered from the Dead Sea, where it occurs at 55,000 parts per million (ppm).

The sea appears in human culture in contradictory ways, as both powerful but serene and as beautiful but dangerous. It has its place in literature, art, poetry, film, theatre, classical music, mythology and dream interpretation. The Ancient history, Ancients personified it, believing it to be under the control of a List of water deities, being who needed to be appeased, and symbolically, it has been perceived as a hostile environment populated by fantastic creatures; the Leviathan of the Bible, Scylla in Greek mythology, Isonade in Japanese mythology, and the kraken of late Norse mythology.

The sea and ships have been Marine art, depicted in art ranging from simple drawings on the walls of huts in Lamu Archipelago, Lamu to seascapes by J. M. W. Turner, Joseph Turner. In Dutch Golden Age painting, artists such as Jan Porcellis, Hendrick Dubbels, Willem van de Velde the Elder and Willem van de Velde the Younger, his son, and Ludolf Bakhuizen celebrated the sea and the Dutch navy at the peak of its military prowess. The Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai created colour Printmaking, prints of the moods of the sea, including ''The Great Wave off Kanagawa''.

In Islam, Islamic tradition, the sea symbolizes both the mercy and might of God, serving as a powerful sign (ayah) of divine creation and control over nature. The Quran, Qur’an frequently references the sea to illustrate God’s benevolence, as in: ''"It is He who subjected the sea so that you may eat fresh meat from it and extract ornaments which you wear"'' (Qur’an 16:14), while also portraying it as a place of trial and humility, as seen in verses that describe the helplessness of humans during storms at sea (Qur’an 10:22). The sea’s dual nature, as a source of sustenance and a manifestation of divine power, reflects a broader Islamic perspective that views natural elements as signs pointing to the oneness and majesty of God. This contrasts with certain other religious traditions; for instance, the sea in biblical literature is often associated with chaos and danger , while in Hinduism, Hindu mythology, it plays a role in cosmic cycles such as the Samudra Manthana, Samudra Manthan, the churning of the ocean. Islamic scholarship, including classical Tafsir, tafsir (Qur’anic exegesis), emphasizes that the sea is not merely a physical reality but a theological symbol that calls believers to reflect on God’s greatness and their own dependence on Him.

Music too has been inspired by the ocean, sometimes by composers who lived or worked near the shore and saw its many different aspects. Sea shanty, Sea shanties, songs that were chanted by mariners to help them perform arduous tasks, have been woven into compositions and impressions in music have been created of calm waters, crashing waves and storms at sea.

As a symbol, the sea has for centuries played a role in literature, poetry and dreams. Sometimes it is there just as a gentle background but often it introduces such themes as storm, shipwreck, battle, hardship, disaster, the dashing of hopes and death. In his epic poetry, epic poem the ''Odyssey'', written in the eighth century BC, Homer describes the ten-year voyage of the Greek hero Odysseus who struggles to return home across the sea's many hazards after the war described in the ''Iliad''. The sea is a recurring theme in the Haiku poems of the Japanese Edo period poet Matsuo Bashō (松尾 芭蕉) (1644–1694). In the works of psychiatrist Carl Jung, the sea symbolizes the personal and the collective unconscious in dream interpretation, the depths of the sea symbolizing the depths of the unconscious mind.

The sea appears in human culture in contradictory ways, as both powerful but serene and as beautiful but dangerous. It has its place in literature, art, poetry, film, theatre, classical music, mythology and dream interpretation. The Ancient history, Ancients personified it, believing it to be under the control of a List of water deities, being who needed to be appeased, and symbolically, it has been perceived as a hostile environment populated by fantastic creatures; the Leviathan of the Bible, Scylla in Greek mythology, Isonade in Japanese mythology, and the kraken of late Norse mythology.

The sea and ships have been Marine art, depicted in art ranging from simple drawings on the walls of huts in Lamu Archipelago, Lamu to seascapes by J. M. W. Turner, Joseph Turner. In Dutch Golden Age painting, artists such as Jan Porcellis, Hendrick Dubbels, Willem van de Velde the Elder and Willem van de Velde the Younger, his son, and Ludolf Bakhuizen celebrated the sea and the Dutch navy at the peak of its military prowess. The Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai created colour Printmaking, prints of the moods of the sea, including ''The Great Wave off Kanagawa''.

In Islam, Islamic tradition, the sea symbolizes both the mercy and might of God, serving as a powerful sign (ayah) of divine creation and control over nature. The Quran, Qur’an frequently references the sea to illustrate God’s benevolence, as in: ''"It is He who subjected the sea so that you may eat fresh meat from it and extract ornaments which you wear"'' (Qur’an 16:14), while also portraying it as a place of trial and humility, as seen in verses that describe the helplessness of humans during storms at sea (Qur’an 10:22). The sea’s dual nature, as a source of sustenance and a manifestation of divine power, reflects a broader Islamic perspective that views natural elements as signs pointing to the oneness and majesty of God. This contrasts with certain other religious traditions; for instance, the sea in biblical literature is often associated with chaos and danger , while in Hinduism, Hindu mythology, it plays a role in cosmic cycles such as the Samudra Manthana, Samudra Manthan, the churning of the ocean. Islamic scholarship, including classical Tafsir, tafsir (Qur’anic exegesis), emphasizes that the sea is not merely a physical reality but a theological symbol that calls believers to reflect on God’s greatness and their own dependence on Him.

Music too has been inspired by the ocean, sometimes by composers who lived or worked near the shore and saw its many different aspects. Sea shanty, Sea shanties, songs that were chanted by mariners to help them perform arduous tasks, have been woven into compositions and impressions in music have been created of calm waters, crashing waves and storms at sea.

As a symbol, the sea has for centuries played a role in literature, poetry and dreams. Sometimes it is there just as a gentle background but often it introduces such themes as storm, shipwreck, battle, hardship, disaster, the dashing of hopes and death. In his epic poetry, epic poem the ''Odyssey'', written in the eighth century BC, Homer describes the ten-year voyage of the Greek hero Odysseus who struggles to return home across the sea's many hazards after the war described in the ''Iliad''. The sea is a recurring theme in the Haiku poems of the Japanese Edo period poet Matsuo Bashō (松尾 芭蕉) (1644–1694). In the works of psychiatrist Carl Jung, the sea symbolizes the personal and the collective unconscious in dream interpretation, the depths of the sea symbolizing the depths of the unconscious mind.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

{{Featured article Seas, Bodies of water Coastal and oceanic landforms Lists of landforms Oceans, * Articles containing video clips

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Indian, Southern Ocean ...

, the interconnected body of seawater

Seawater, or sea water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximat ...

s that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order sections of the oceanic sea (e.g. the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

), or certain large, nearly landlocked bodies of water.

The salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

of water bodies varies widely, being lower near the surface and the mouths of large river

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside Subterranean river, caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of ...

s and higher in the depths of the ocean; however, the relative proportions of dissolved salts vary little across the oceans. The most abundant solid dissolved in seawater

Seawater, or sea water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximat ...

is sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

. The water also contains salts

In chemistry, a salt or ionic compound is a chemical compound consisting of an assembly of positively charged ions ( cations) and negatively charged ions (anions), which results in a compound with no net electric charge (electrically neutral). ...

of magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

, calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

, potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

, and mercury, among other elements, some in minute concentrations. A wide variety of organisms, including bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, protist

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancest ...

s, algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

, plants, fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, and animals live in various marine habitat

A marine habitat is a habitat that supports marine life. Marine life depends in some way on the seawater, saltwater that is in the sea (the term ''marine'' comes from the Latin ''mare'', meaning sea or ocean). A habitat is an ecological or Na ...

s and ecosystems

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

throughout the seas. These range vertically from the sunlit surface and shoreline

A coast (coastline, shoreline, seashore) is the land next to the sea or the line that forms the boundary between the land and the ocean or a lake. Coasts are influenced by the topography of the surrounding landscape and by aquatic erosion, su ...

to the great depths and pressures of the cold, dark abyssal zone

The abyssal zone or abyssopelagic zone is a layer of the pelagic zone of the ocean. The word ''abyss'' comes from the Greek word (), meaning "bottomless". At depths of , this zone remains in perpetual darkness. It covers 83% of the total area ...

, and in latitude from the cold waters under polar ice cap

A polar ice cap or polar cap is a high-latitude region of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite that is covered in ice.

There are no requirements with respect to size or composition for a body of ice to be termed a polar ice cap, nor a ...

s to the warm waters of coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

s in tropical regions. Many of the major groups of organisms evolved in the sea and life may have started there.

The ocean moderates Earth's climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in a region, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteoro ...

and has important roles in the water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

, carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

, and nitrogen cycle

The nitrogen cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which nitrogen is converted into multiple chemical forms as it circulates among atmosphere, atmospheric, terrestrial ecosystem, terrestrial, and marine ecosystems. The conversion of nitrogen can ...

s. The surface of water interacts with the atmosphere, exchanging properties such as particle

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

s and temperature, as well as currents

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (hy ...

. Surface currents are the water currents that are produced by the atmosphere's currents and its winds

Wind is the natural movement of atmosphere of Earth, air or other gases relative to a planetary surface, planet's surface. Winds occur on a range of scales, from thunderstorm flows lasting tens of minutes, to local breezes generated by heatin ...

blowing over the surface of the water, producing wind wave

In fluid dynamics, a wind wave, or wind-generated water wave, is a surface wave that occurs on the free surface of bodies of water as a result of the wind blowing over the water's surface. The contact distance in the direction of the wind is ...

s, setting up through drag slow but stable circulations of water, as in the case of the ocean sustaining deep-sea ocean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of seawater generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours, sh ...

s. Deep-sea currents, known together as the global conveyor belt, carry cold water from near the poles to every ocean and significantly influence Earth's climate. Tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s, the generally twice-daily rise and fall of sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an mean, average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal Body of water, bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical ...

s, are caused by Earth's rotation and the gravitational effects of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

and, to a lesser extent, of the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

. Tides may have a very high range

Range may refer to:

Geography

* Range (geographic), a chain of hills or mountains; a somewhat linear, complex mountainous or hilly area (cordillera, sierra)

** Mountain range, a group of mountains bordered by lowlands

* Range, a term used to i ...

in bays or estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environm ...

. Submarine earthquake

A submarine, undersea, or underwater earthquake is an earthquake that occurs underwater at the seabed, bottom of a body of water, especially an ocean. They are the leading cause of tsunamis. The magnitude can be measured scientifically by the use ...

s arising from tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

movements under the oceans can lead to destructive tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

s, as can volcanoes, huge landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, rockslips or rockslides, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, mudflows, shallow or deep-seated slope failures and debris flows. Landslides ...

s, or the impact of large meteorite

A meteorite is a rock (geology), rock that originated in outer space and has fallen to the surface of a planet or Natural satellite, moon. When the original object enters the atmosphere, various factors such as friction, pressure, and chemical ...

s.

The seas have been an integral element for humans throughout history and culture. Humans harnessing and studying the seas have been recorded since ancient times and evidenced well into prehistory

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

, while its modern scientific study is called oceanography

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of to ...

and maritime space is governed by the law of the sea

Law of the sea (or ocean law) is a body of international law governing the rights and duties of State (polity), states in Ocean, maritime environments. It concerns matters such as navigational rights, sea mineral claims, and coastal waters juris ...

, with admiralty law

Maritime law or admiralty law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and conflict of laws, private international law governing the relations ...

regulating human interactions at sea. The seas provide substantial supplies of food for humans, mainly fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, but also shellfish

Shellfish, in colloquial and fisheries usage, are exoskeleton-bearing Aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrates used as Human food, food, including various species of Mollusca, molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish ...

, mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

and seaweed

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of ''Rhodophyta'' (red), '' Phaeophyta'' (brown) and ''Chlorophyta'' (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such as ...

, whether caught by fishermen or farmed underwater. Other human uses of the seas include trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

, travel, mineral extraction

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

, power generation, warfare

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of State (polity), states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or betwe ...

, and leisure activities such as swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, such as saltwater or freshwater environments, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Swimmers achieve locomotion by coordinating limb and body movements to achieve hydrody ...

, sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship, sailboat, raft, Windsurfing, windsurfer, or Kitesurfing, kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat) or on ''land'' (Land sa ...

, and scuba diving

Scuba diving is a Diving mode, mode of underwater diving whereby divers use Scuba set, breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface breathing gas supply, and therefore has a limited but variable endurance. The word ''scub ...

. Many of these activities create marine pollution

Marine pollution occurs when substances used or spread by humans, such as industrial waste, industrial, agricultural pollution, agricultural, and municipal solid waste, residential waste; particle (ecology), particles; noise; excess carbon dioxi ...

.

Definition

Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

, Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

, Indian, Southern and Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

s. "Sea." ''Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary'', Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sea . Accessed 14 March 2021. However, the word "sea" can also be used for many specific, much smaller bodies of seawater, such as the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

or the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

. There is no sharp distinction between seas and ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Indian, Southern Ocean ...

s, though generally seas are smaller, and are often partly (as marginal sea

This is a list of seas of the World Ocean, including marginal seas, areas of water, various gulfs, bights, bays, and straits. In many cases it is a matter of tradition for a body of water to be named a sea or a bay, etc., therefore all these ...

s or particularly as a mediterranean sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

) or wholly (as inland seas

An inland sea (also known as an epeiric sea or an epicontinental sea) is a continental body of water which is very large in area and is either completely surrounded by dry land (landlocked), or connected to an ocean by a river, strait or " arm of ...

) enclosed by land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of Earth not submerged by the ocean or another body of water. It makes up 29.2% of Earth's surface and includes all continents and islands. Earth's land sur ...

. However, an exception to this is the Sargasso Sea

The Sargasso Sea () is a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by four currents forming an ocean gyre. Unlike all other regions called seas, it is the only one without land boundaries. It is distinguished from other parts of the Atlantic Oc ...

which has no coastline and lies within a circular current, the North Atlantic Gyre

The North Atlantic Gyre of the Atlantic Ocean is one of five great oceanic gyres. It is a circular ocean current, with offshoot eddies and sub-gyres, across the North Atlantic from the Intertropical Convergence Zone (calms or doldrums) to the pa ...

. Seas are generally larger than lakes and contain salt water, but the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee (, Judeo-Aramaic languages, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ), also called Lake Tiberias, Genezareth Lake or Kinneret, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth ...

is a freshwater lake. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international treaty that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , 169 sov ...

states that all of the ocean is "sea".

Legal definition

Thelaw of the sea

Law of the sea (or ocean law) is a body of international law governing the rights and duties of State (polity), states in Ocean, maritime environments. It concerns matters such as navigational rights, sea mineral claims, and coastal waters juris ...

has at its centre the definition of the boundaries of the ocean, clarifying its application in marginal sea

This is a list of seas of the World Ocean, including marginal seas, areas of water, various gulfs, bights, bays, and straits. In many cases it is a matter of tradition for a body of water to be named a sea or a bay, etc., therefore all these ...

s. But what bodies of water other than the sea the law applies to is being crucially negotiated in the case of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

and its status as "sea", basically revolving around the issue of the Caspian Sea about either being factually an oceanic sea or only a saline body of water and therefore solely a sea in the sense of the common use of the word, like all other saltwater lakes called sea.

Physical science

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

is the only known planet

A planet is a large, Hydrostatic equilibrium, rounded Astronomical object, astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets b ...

with seas of liquid water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

on its surface, although Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

possesses ice caps

In glaciology, an ice cap is a mass of ice that covers less than of land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of Earth not submerged by the ocean or another body of water. It makes up 29.2% ...

and similar planets in other solar systems may have oceans. Earth's of sea contain about 97.2 percent of its known water and covers approximately 71 percent of its surface. Another 2.15% of Earth's water is frozen, found in the sea ice covering the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

, the ice cap covering Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

and its adjacent seas, and various glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s and surface deposits around the world. The remainder (about 0.65% of the whole) form underground reservoirs or various stages of the water cycle

The water cycle (or hydrologic cycle or hydrological cycle) is a biogeochemical cycle that involves the continuous movement of water on, above and below the surface of the Earth across different reservoirs. The mass of water on Earth remains fai ...

, containing the freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include non-salty mi ...

encountered and used by most terrestrial life: vapor

In physics, a vapor (American English) or vapour (Commonwealth English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is a substance in the gas phase at a temperature lower than its critical temperature,R ...

in the air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

, the cloud

In meteorology, a cloud is an aerosol consisting of a visible mass of miniature liquid droplets, frozen crystals, or other particles, suspended in the atmosphere of a planetary body or similar space. Water or various other chemicals may ...

s it slowly forms, the rain

Rain is a form of precipitation where water drop (liquid), droplets that have condensation, condensed from Water vapor#In Earth's atmosphere, atmospheric water vapor fall under gravity. Rain is a major component of the water cycle and is res ...

falling from them, and the lake

A lake is often a naturally occurring, relatively large and fixed body of water on or near the Earth's surface. It is localized in a basin or interconnected basins surrounded by dry land. Lakes lie completely on land and are separate from ...

s and river

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside Subterranean river, caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of ...

s spontaneously formed as its waters flow again and again to the sea.NOAA

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA ) is an American scientific and regulatory agency charged with forecasting weather, monitoring oceanic and atmospheric conditions, charting the seas, conducting deep-sea exploratio ...

.Lesson 7: The Water Cycle

" in ''Ocean Explorer''. The scientific study of

water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

and Earth's water cycle

The water cycle (or hydrologic cycle or hydrological cycle) is a biogeochemical cycle that involves the continuous movement of water on, above and below the surface of the Earth across different reservoirs. The mass of water on Earth remains fai ...

is hydrology

Hydrology () is the scientific study of the movement, distribution, and management of water on Earth and other planets, including the water cycle, water resources, and drainage basin sustainability. A practitioner of hydrology is called a hydro ...

; hydrodynamics

In physics, physical chemistry and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids – liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including (the study of air and other gases in ...

studies the physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

of water in motion. The more recent study of the sea in particular is oceanography

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of to ...

. This began as the study of the shape of the ocean's currents

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (hy ...

but has since expanded into a large and multidisciplinary

An academic discipline or academic field is a subdivision of knowledge that is taught and researched at the college or university level. Disciplines are defined (in part) and recognized by the academic journals in which research is published, ...

field:Monkhouse, F.J. (1975) ''Principles of Physical Geography''. pp. 327–328. Hodder & Stoughton. . it examines the properties of seawater

Seawater, or sea water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximat ...

; studies waves

United States Naval Reserve (Women's Reserve), better known as the WAVES (for Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), was the women's branch of the United States Naval Reserve during World War II. It was established on July 21, 1942, ...

, tides

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

, and currents

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (hy ...

; charts coastlines and maps the seabeds; and studies marine life

Marine life, sea life or ocean life is the collective ecological communities that encompass all aquatic animals, aquatic plant, plants, algae, marine fungi, fungi, marine protists, protists, single-celled marine microorganisms, microorganisms ...

. The subfield dealing with the sea's motion, its forces, and the forces acting upon it is known as physical oceanography

Physical oceanography is the study of physical conditions and physical processes within the ocean, especially the motions and physical properties of ocean waters.

Physical oceanography is one of several sub-domains into which oceanography is div ...

. Marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

(biological oceanography) studies the plants

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria to produce sugars f ...

, animals

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a ...

, and other organisms inhabiting marine ecosystems. Both are informed by chemical oceanography

Marine chemistry, also known as ocean chemistry or chemical oceanography, is the study of the chemical composition and processes of the world’s oceans, including the interactions between seawater, the atmosphere, the seafloor, and marine organ ...

, which studies the behavior of elements and molecules

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry ...

within the oceans: particularly, at the moment, the ocean's role in the carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is a part of the biogeochemical cycle where carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of Earth. Other major biogeochemical cycles include the nitrogen cycle and the water cycl ...

and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

's role in the increasing acidification of seawater. Marine and maritime geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

charts the shape and shaping of the sea, while marine geology

Marine geology or geological oceanography is the study of the history and structure of the ocean floor. It involves geophysical, Geochemistry, geochemical, Sedimentology, sedimentological and paleontological investigations of the ocean floor and ...

(geological oceanography) has provided evidence of continental drift

Continental drift is a highly supported scientific theory, originating in the early 20th century, that Earth's continents move or drift relative to each other over geologic time. The theory of continental drift has since been validated and inc ...

and the composition

Composition or Compositions may refer to:

Arts and literature

*Composition (dance), practice and teaching of choreography

* Composition (language), in literature and rhetoric, producing a work in spoken tradition and written discourse, to include ...

and structure of the Earth

The internal structure of Earth are the layers of the Earth, excluding its atmosphere and hydrosphere. The structure consists of an outer silicate solid crust, a highly viscous asthenosphere, and solid mantle, a liquid outer core whose flow g ...

, clarified the process of sedimentation

Sedimentation is the deposition of sediments. It takes place when particles in suspension settle out of the fluid in which they are entrained and come to rest against a barrier. This is due to their motion through the fluid in response to th ...

, and assisted the study of volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism, volcanicity, or volcanic activity is the phenomenon where solids, liquids, gases, and their mixtures erupt to the surface of a solid-surface astronomical body such as a planet or a moon. It is caused by the presence of a he ...

and earthquakes

An earthquakealso called a quake, tremor, or tembloris the shaking of the Earth's surface resulting from a sudden release of energy in the lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from those so weak they c ...

.

Seawater

Salinity

A characteristic of seawater is that it is salty. Salinity is usually measured in parts per thousand ( ‰ or per mil), and the open ocean has about solids per litre, a salinity of 35 ‰. The Mediterranean Sea is slightly higher at 38 ‰, while the salinity of the northern Red Sea can reach 41‰. In contrast, some landlockedhypersaline lake

A hypersaline lake is a landlocked body of water that contains significant concentrations of sodium chloride, brines, and other salts, with saline levels surpassing those of ocean water (3.5%, i.e. ).

Specific microbial species can thrive i ...

s have a much higher salinity, for example, the Dead Sea