Schlesinger Jr., Arthur M. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

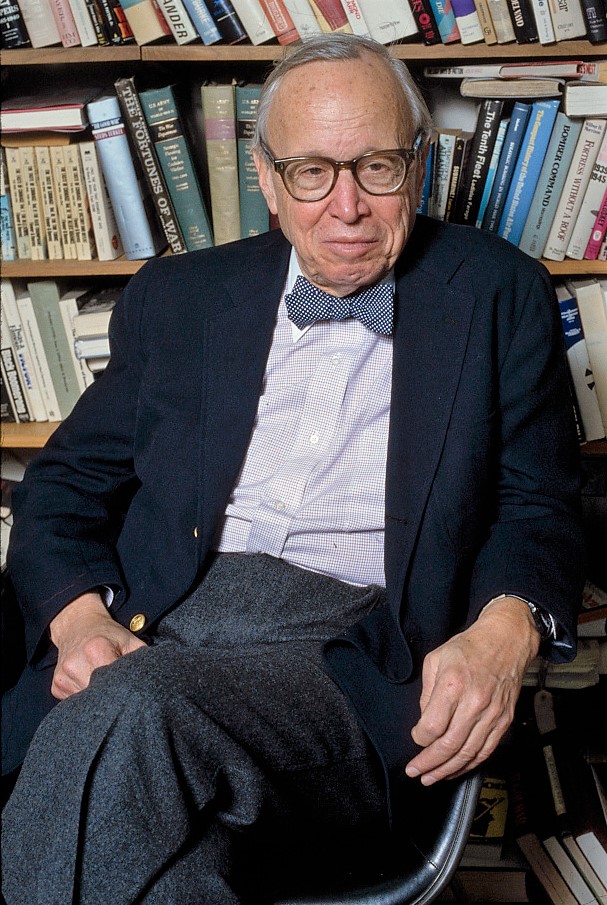

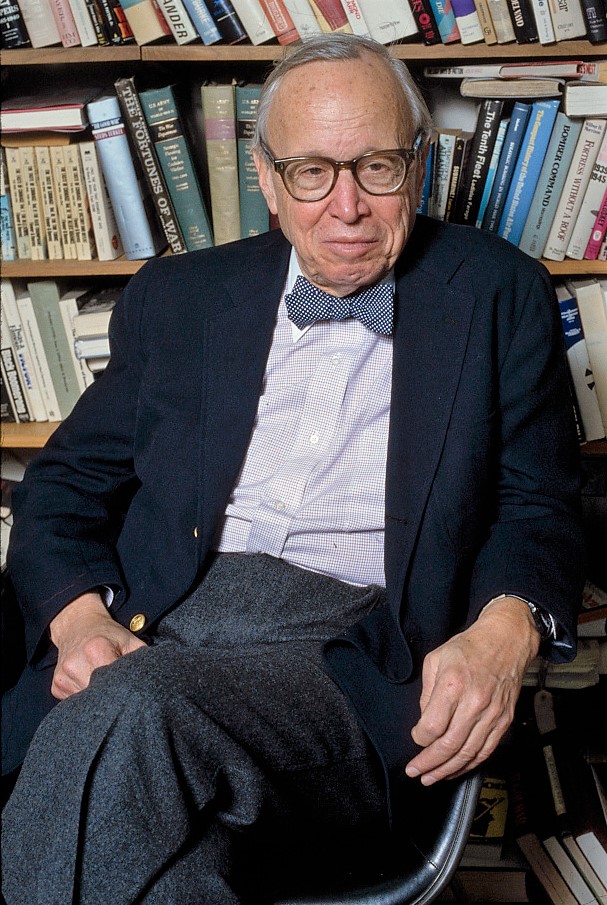

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. (; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a specialist in American history, much of Schlesinger's work explored the history of 20th-century American liberalism. In particular, his work focused on leaders such as Harry S. Truman, Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Robert F. Kennedy. In the 1952 and 1956 presidential campaigns, he was a primary speechwriter and adviser to the Democratic presidential nominee, Adlai Stevenson II. Schlesinger served as special assistant and "court historian" to President Kennedy from 1961 to 1963. He wrote a detailed account of the Kennedy administration, from the 1960 presidential campaign to the president's state funeral, titled '' A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House'', which won the 1966

Schlesinger returned to teaching in 1966 as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of the Humanities at the CUNY Graduate Center. After his retirement from teaching in 1994, he remained an active member of the Graduate Center community as an emeritus professor until his death.

Schlesinger returned to teaching in 1966 as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of the Humanities at the CUNY Graduate Center. After his retirement from teaching in 1994, he remained an active member of the Graduate Center community as an emeritus professor until his death.

"The Future of Socialism"

'' Partisan Review'', May/June 1947.

"The Crisis of American Masculinity"

''Esquire'', November 1958.

"The Many Faces of Communism, Part 1: The Theological Society"

''

"Origins of the Cold War"

''

"Against Academic Apartheid"

'' The Social Contract'', Vol. 1, No. 1, Inaugural Issue, Fall 1990.

''Orestes A. Brownson: A Pilgrim's Progress''

*194

''The Age of Jackson''

*1949 '' The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom'' *1950 ''What About Communism?'' *1951 ''The General and the President, and the Future of American Foreign Policy'' *195

''The Crisis of the Old Order: 1919–1933'' (''The Age of Roosevelt'', Vol. I)

*195

''The Coming of the New Deal: 1933–1935'' (''The Age of Roosevelt'', Vol. II)

*196

''The Politics of Upheaval: 1935–1936'' (''The Age of Roosevelt'', Vol. III)

*1960 ''Kennedy or Nixon: Does It Make Any Difference?'' *196

''The Politics of Hope''

*1963 ''Paths of American Thought'' (ed. with Morton White) *1965 '' A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House'' *1965 ''The MacArthur Controversy and American Foreign Policy'' *196

''The Bitter Heritage: Vietnam and American Democracy, 1941–1966''

*1967 ''Congress and the Presidency: Their Role in Modern Times'' *196

''Violence: America in the Sixties''

*1969 ''The Crisis of Confidence: Ideas, Power, and Violence in America'' *197

''The Origins of the Cold War''

*1973 '' The Imperial Presidency'' – reissued in 1989 (with epilogue) and 2004 *197

''Robert Kennedy and His Times''

– adapted into a 1985 TV miniseries *1983 ''Creativity in Statecraft'' *1983 ''

''Journals 1952–2000''

*2011 ''Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life With John F Kennedy'' (Mrs. Kennedy's interview shortly after her husband's assassination) Besides writing biographies he also wrote a foreword to a book on Vladimir Putin which came out in 2003 under the same name and was published by

Niebuhr Medal

Awarded by Elmhurst College to an individual who exemplifies the ideals of Reinhold and

online book review

* Diggins, John Patrick, ed. ''The Liberal Persuasion: Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and the Challenge of the American Past,'' Princeton UP, 1997

online free

*Feller, Daniel, "Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.," in Robert Allen Rutland, ed. ''Clio's Favorites: Leading Historians of the United States, 1945–2000'' U of Missouri Press, 2000; pp. 156–169. * Martin, John Bartlow. ''Adlai Stevenson of Illinois.'' New York: Doubleday. 1976. * Thomas Meaney, "The

''Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.''

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum, February 15, 2006. * Wilentz, Sean, "The High Table Liberal" (review of

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. papers 1922–2007

held by the Manuscripts and Archives Division,

''In Depth'' interview with Schlesinger, December 3, 2000

* Eisler, Kim.

, ''Washingtonian'', March 6, 2008.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and "court philosopher" of the Kennedy administration was 89 when he died.

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. 1917 births 2007 deaths 20th-century American historians American male non-fiction writers 21st-century American historians 21st-century American male writers American cultural critics American people of Austrian descent American people of English descent American people of German-Jewish descent American Unitarians Cold War historians Critics of multiculturalism Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Historians of the United States Kennedy administration personnel Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters National Book Award winners National Humanities Medal recipients New York (state) Democrats People of the Office of Strategic Services People of the United States Office of War Information Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography winners Bancroft Prize winners Pulitzer Prize for History winners Phillips Exeter Academy alumni Harvard College alumni Harvard Fellows Harvard University faculty Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Social critics World War II spies for the United States The Century Foundation 20th-century American male writers Presidents of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Members of the American Philosophical Society

Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography

The Pulitzer Prize for Biography is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It has been presented since 1917 for a distinguished biography, autobiography or memoir by an American author o ...

.

In 1968, Schlesinger actively supported the presidential campaign of Senator Robert F. Kennedy, which ended with Kennedy's assassination in Los Angeles. Schlesinger wrote a popular biography, ''Robert Kennedy and His Times'', several years later. He later popularized the term " imperial presidency" during the Nixon administration in his 1973 book of the same name.

Early life and career

Schlesinger was born inColumbus, Ohio

Columbus () is the state capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest, after Chicago, and t ...

, the son of Elizabeth Harriet (née Bancroft) and Arthur M. Schlesinger

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Sr. (; February 27, 1888 – October 30, 1965) was an American historian who taught at Harvard University, pioneering social history and urban history. He was a Progressive Era intellectual who stressed material cau ...

(1888–1965), who was an influential social historian at Ohio State University and Harvard University, where he directed many PhD dissertations in American history. His paternal grandfather was a Prussian Jew who converted to Protestantism and then married an Austrian Catholic. His mother, a Mayflower descendant

The General Society of ''Mayflower'' Descendants — commonly called the Mayflower Society — is a hereditary organization of individuals who have documented their descent from at least one of the 102 passengers who arrived on the ''Mayflower'' ...

, was of German and New England ancestry, as well as a relative of historian George Bancroft, according to family tradition. His family practiced Unitarianism.

Schlesinger attended the Phillips Exeter Academy

(not for oneself) la, Finis Origine Pendet (The End Depends Upon the Beginning) gr, Χάριτι Θεοῦ (By the Grace of God)

, location = 20 Main Street

, city = Exeter, New Hampshire

, zipcode ...

, New Hampshire, and received his first degree at the age of 20 from Harvard College, where he graduated ''summa cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some Sou ...

'' in 1938. After spending the 1938–1939 academic year at Peterhouse, Cambridge

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Today, Peterhouse has 254 undergraduates, 116 full-time graduate students and 54 fellows. It is quite ...

as a Henry Fellow, he was appointed to a three-year Junior Fellowship in the Harvard Society of Fellows in the fall of 1939. At the time, Fellows were not allowed to pursue advanced degrees, "a requirement intended to keep them off the standard academic treadmill"; as such, Schlesinger would never earn a doctorate. His fellowship was interrupted by the United States entering World War II. After failing his military medical examination, Schlesinger joined the Office of War Information. From 1943 to 1945, he served as an intelligence analyst in the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

, a precursor to the CIA.

Schlesinger's service in the OSS allowed him time to complete his first Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

–winning book, ''The Age of Jackson'', in 1945. From 1946 to 1954, he was an associate professor at Harvard, becoming a full professor in 1954.

Political activities before 1960

In 1947, Schlesinger, together with former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Minneapolis mayor and futureSenator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and Vice President Hubert Humphrey, economist and longtime friend John Kenneth Galbraith, and Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, founded Americans for Democratic Action. Schlesinger acted as the ADA's national chairman from 1953 to 1954.

After President Harry S. Truman announced he would not run for a second full term in the 1952 presidential election, Schlesinger became the primary speechwriter for and an ardent supporter of Governor Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois. In the 1956 election, Schlesinger, along with 30-year-old Robert F. Kennedy, again worked on Stevenson's campaign staff. Schlesinger supported the nomination of Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy as Stevenson's vice-presidential running mate, but at the Democratic convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

, Kennedy came second in the vice-presidential balloting, losing to Senator Estes Kefauver

Carey Estes Kefauver (;

July 26, 1903 – August 10, 1963) was an American politician from Tennessee. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1939 to 1949 and in the Senate from 1949 until his d ...

of Tennessee.

Schlesinger had known John F. Kennedy since attending Harvard and increasingly socialized with Kennedy and his wife Jacqueline in the 1950s. In 1954, '' The Boston Post'' publisher John Fox Jr. planned a series of newspaper pieces labeling several Harvard figures, including Schlesinger, as " reds"; Kennedy intervened on Schlesinger's behalf, which Schlesinger recounted in ''A Thousand Days''.

During the 1960 campaign, Schlesinger supported Kennedy, causing much consternation to Stevenson loyalists. At the time, however, Kennedy was an active candidate while Stevenson refused to run unless he was drafted at the convention. After Kennedy won the nomination, Schlesinger helped the campaign as a (sometime) speechwriter, speaker, and member of the ADA. He also wrote the book ''Kennedy or Nixon: Does It Make Any Difference?'' in which he lauded Kennedy's abilities and scorned Vice President Richard M. Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

as having "no ideas, only methods.... He cares about winning."

Kennedy administration

After the election, the president-elect offered Schlesinger an ambassadorship and Assistant Secretary of State for Cultural Relations before Robert Kennedy proposed that Schlesinger serve as a "sort of roving reporter and troubleshooter." Schlesinger quickly accepted, and on January 30, 1961, he resigned from Harvard and was appointed Special Assistant to the President. He worked primarily on Latin American affairs and as a speechwriter during his tenure in the White House. In February 1961, Schlesinger was first told of the "Cuba operation," which would eventually become the Bay of Pigs Invasion. He opposed the plan in a memorandum to the president: "at one stroke you would dissipate all the extraordinary good will which has been rising toward the new Administration through the world. It would fix a malevolent image of the new Administration in the minds of millions."''A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House'', Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. He, however, suggested, During the Cabinet deliberations, he "shrank into a chair at the far end of the table and listened in silence" as the Joint Chiefs and CIA representatives lobbied the president for an invasion. Along with his friend, Senator William Fulbright, Schlesinger sent several memos to the president opposing the strike; however, during the meetings, he held back his opinion, reluctant to undermine the President's desire for a unanimous decision. Following the overt failure of the invasion, Schlesinger later lamented, "In the months after the Bay of Pigs, I bitterly reproached myself for having kept so silent during those crucial discussions in the cabinet room. ... I can only explain my failure to do more than raise a few timid questions by reporting that one's impulse to blow the whistle on this nonsense was simply undone by the circumstances of the discussion." After the furor died down, Kennedy joked that Schlesinger "wrote me a memorandum that will look pretty good when he gets around to writing his book on my administration. Only he better not publish that memorandum while I'm still alive!" During theCuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, Schlesinger was not a member of the executive committee of the National Security Council ( EXCOMM) but helped UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson Adlai Stevenson may refer to:

* Adlai Stevenson I (1835–1914), U.S. Vice President (1893–1897) and Congressman (1879–1881)

* Adlai Stevenson II (1900–1965), Governor of Illinois (1949–1953), U.S. presidential candida ...

draft his presentation of the crisis to the UN Security Council.

In October 1962, Schlesinger became afraid of ''"a tremendous advantage"'', which ''"all-out Soviet commitment to cybernetics

Cybernetics is a wide-ranging field concerned with circular causality, such as feedback, in regulatory and purposive systems. Cybernetics is named after an example of circular causal feedback, that of steering a ship, where the helmsperson m ...

"'' would provide the Soviets. Schlesinger further warned that ''"by 1970 the USSR may have a radically new production technology, involving total enterprises or complexes of industries, managed by closed-loop, feedback control employing self-teaching computer

Machine learning (ML) is a field of inquiry devoted to understanding and building methods that 'learn', that is, methods that leverage data to improve performance on some set of tasks. It is seen as a part of artificial intelligence.

Machine ...

s"''. The cause was a pre-vision of an algorithmic governance of economy by an internet-like computer network authored by Soviet scientists, particularly Alexander Kharkevich.

After President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, Schlesinger resigned his position in January 1964. He wrote a memoir/history of the Kennedy administration, ''A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House'', which won him his second Pulitzer Prize in 1965.

Later career

Schlesinger returned to teaching in 1966 as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of the Humanities at the CUNY Graduate Center. After his retirement from teaching in 1994, he remained an active member of the Graduate Center community as an emeritus professor until his death.

Schlesinger returned to teaching in 1966 as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of the Humanities at the CUNY Graduate Center. After his retirement from teaching in 1994, he remained an active member of the Graduate Center community as an emeritus professor until his death.

Later politics

After his service for the Kennedy administration, he continued to be a Kennedy loyalist for the rest of his life, campaigning for Robert Kennedy's tragic presidential campaign in 1968 and for SenatorEdward M. Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

in 1980. Upon the request of Robert Kennedy's widow, Ethel Kennedy, he wrote the biography ''Robert Kennedy and His Times'', which was published in 1978.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, he greatly criticized Richard Nixon as both a candidate and president. His prominent status as a liberal Democrat and outspoken disdain of Nixon led to his placement on the master list of Nixon's political opponents

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

. Ironically, Nixon would become his next-door neighbor in the years following the Watergate scandal.

After he retired from teaching, he remained involved in politics for the rest of his life through his books and public speaking tours. Schlesinger was a critic of the Clinton Administration, resisting President Clinton's cooptation of his "Vital Center" concept in an article for Slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

in 1997. Schlesinger was also a critic of the 2003 Iraq War and called it a misadventure. He put much blame on the media for not covering a reasoned case against the war.

Personal life

Schlesinger's name at birth was Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; since his mid-teens, he had instead used the signature ''Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.'' He had five children, four from his first marriage to author and artist Marian Cannon Schlesinger and a son and stepson from his second marriage, to Alexandra Emmet, also an artist. * Stephen Schlesinger (b. 1942), a notable author of books on foreign affairs and former director of the World Policy Institute *Katharine Kinderman (1942–2004), an author and producer, who was married to Gibbs Kinderman and later Thomas Tiffany *Christina Schlesinger

Christina Schlesinger (born November 19, 1946) is an American painter and muralist. Daughter of historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., she sought independence from her family's fame, practiced “protest art”, and came out as a lesbian. She made s ...

(b. 1946), a prominent artist and muralist

*Andrew Schlesinger, writer and editor

*Robert Schlesinger

Robert Schlesinger is an American writer and liberal commentator focusing on politics and political communications.

Biography

A New York City native, he is a graduate of Middlebury College. He now lives in Alexandria, Virginia, with his wife and t ...

, writer and editor

As a prominent Democrat and historian, Schlesinger maintained a very active social life. His wide circle of friends and associates included politicians, actors, writers, and artists, spanning several decades. Among his friends and associates were President John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Edward M. Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

, Adlai E. Stevenson, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis ( ; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was an American socialite, writer, photographer, and book editor who served as first lady of the United States from 1961 to 1963, as the wife of President John F. Kennedy. A pop ...

, John Kenneth Galbraith, W. Averell and Pamela Harriman, Steve

''yes'Steve is a masculine given name, usually a short form (hypocorism) of Steven or Stephen

Notable people with the name include:

steve jops

* Steve Abbott (disambiguation), several people

* Steve Adams (disambiguation), several people

* Steve ...

and Jean Kennedy Smith, Ethel Skakel Kennedy

Ethel Kennedy (' Skakel; born April 11, 1928) is an American human rights advocate. She is the widow of U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a sister-in-law of President John F. Kennedy, and the sixth child of George Skakel and Ann Brannack. Shortly a ...

, Ted Sorensen, Eleanor Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr., Alice Roosevelt Longworth, Hubert Humphrey, Henry Kissinger, Marietta Peabody Tree, Ben Bradlee, Joseph Alsop, Evangeline Bruce, William vanden Heuvel, Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer

Nachem Malech Mailer (January 31, 1923 – November 10, 2007), known by his pen name Norman Kingsley Mailer, was an American novelist, journalist, essayist, playwright, activist, filmmaker and actor. In a career spanning over six decades, Mailer ...

, Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

and Katharine Graham, Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

, Walter Lippmann, President Lyndon B. Johnson, Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979), sometimes referred to by his nickname Rocky, was an American businessman and politician who served as the 41st vice president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of t ...

, Lauren Bacall

Lauren Bacall (; born Betty Joan Perske; September 16, 1924 – August 12, 2014) was an American actress. She was named the 20th-greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema by the American Film Institute and received an Academy Honorary Aw ...

, Marlene Dietrich, George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pres ...

, Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy

McGeorge "Mac" Bundy (March 30, 1919 – September 16, 1996) was an American academic who served as the U.S. National Security Advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 through 1966. He was president of the Ford Founda ...

, Jack Valenti

Jack Joseph Valenti (September 5, 1921 – April 26, 2007) was an American political advisor and lobbyist who served as a Special Assistant to U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. He was also the longtime president of the Motion Picture Association ...

, Bill Moyers, Richard Goodwin, Al Gore

Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (born March 31, 1948) is an American politician, businessman, and environmentalist who served as the 45th vice president of the United States from 1993 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton. Gore was the Democratic Part ...

, President Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton.

Career

Education

*1933Phillips Exeter Academy

(not for oneself) la, Finis Origine Pendet (The End Depends Upon the Beginning) gr, Χάριτι Θεοῦ (By the Grace of God)

, location = 20 Main Street

, city = Exeter, New Hampshire

, zipcode ...

*1938 A.B. ''summa cum laude'', Harvard University

*1938–1939 Henry Fellow, Peterhouse, Cambridge

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Today, Peterhouse has 254 undergraduates, 116 full-time graduate students and 54 fellows. It is quite ...

*1939–1942 Society of Fellows, Harvard University

World War II service

*1942–1943 Office of War Information *1943–1945Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

Educator

*1946–1954 Associate Professor of History, Harvard University *1954–1962 Professor of History, Harvard University *1966 Visiting Fellow, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey *1966–1994 Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities, CUNY Graduate Center (Emeritus, 1994–2007)Democratic Party activist

*Among the founders of Americans for Democratic Action *Speechwriter forAdlai Stevenson Adlai Stevenson may refer to:

* Adlai Stevenson I (1835–1914), U.S. Vice President (1893–1897) and Congressman (1879–1881)

* Adlai Stevenson II (1900–1965), Governor of Illinois (1949–1953), U.S. presidential candida ...

's two presidential campaigns in 1952

Events January–February

* January 26 – Black Saturday in Egypt: Rioters burn Cairo's central business district, targeting British and upper-class Egyptian businesses.

* February 6

** Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, becomes m ...

and 1956

Events

January

* January 1 – The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Anglo-Egyptian Condominium ends in Sudan.

* January 8 – Operation Auca: Five U.S. evangelical Christian Missionary, missionaries, Nate Saint, Roger Youderian, Ed McCully, Jim ...

*Speechwriter for John F. Kennedy's campaign in 1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events

January

* Ja ...

*1961–1964 Special Assistant to the President for Latin American affairs and speechwriting

*Speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy's campaign in 1968

The year was highlighted by protests and other unrests that occurred worldwide.

Events January–February

* January 5 – "Prague Spring": Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

* Januar ...

*Speechwriter for George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pres ...

's campaign in 1972

Within the context of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) it was the longest year ever, as two leap seconds were added during this 366-day year, an event which has not since been repeated. (If its start and end are defined using Solar time, me ...

*Active in the presidential campaign of Ted Kennedy in 1980

Events January

* January 4 – U.S. President Jimmy Carter proclaims a grain embargo against the USSR with the support of the European Commission.

* January 6 – Global Positioning System time epoch begins at 00:00 UTC.

* January 9 – ...

Death

On February 28, 2007, Schlesinger had a heart attack while dining with family at a steakhouse in Manhattan. He was taken to New York Downtown Hospital, where he died at the age of 89. His '' New York Times'' obituary described him as a "historian of power." He is buried inMount Auburn Cemetery

Mount Auburn Cemetery is the first rural cemetery, rural, or garden, cemetery in the United States, located on the line between Cambridge, Massachusetts, Cambridge and Watertown, Massachusetts, Watertown in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Middl ...

in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Works

He won aPulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

for History in 1946 for his book ''The Age of Jackson'', covering the intellectual environment of Jacksonian democracy.

His 1949 book '' The Vital Center'' made a case for the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt and was harshly critical of both unregulated capitalism and of those liberals such as Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. S ...

who advocated coexistence with communism.

In his book ''The Politics of Hope'' (1962), Schlesinger terms conservatives the "party of the past" and liberals "the party of hope" and calls for overcoming the division between both parties.

He won a second Pulitzer in the Biography category in 1966 for ''A Thousand Days''.

His 1986 book ''The Cycles of American History,'' a collection of essays and articles, contains "The Cycles of American Politics," an early work on the topic; it was influenced by his father's work on cycles.

He became a leading opponent of multiculturalism in the 1980s and articulated this stance in his book '' The Disuniting of America'' (1991).

Published posthumously in 2007, ''Journals 1952–2000'' is the 894-page distillation of 6,000 pages of Schlesinger diaries on a wide variety of subjects, edited by Andrew and Stephen Schlesinger.

Selected bibliography

This is a partial listing of Schlesinger's published works:Articles

"The Future of Socialism"

'' Partisan Review'', May/June 1947.

"The Crisis of American Masculinity"

''Esquire'', November 1958.

"The Many Faces of Communism, Part 1: The Theological Society"

''

Harper's Magazine

''Harper's Magazine'' is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. Launched in New York City in June 1850, it is the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the U.S. (''Scientific American'' is older, b ...

'', January 1960."Origins of the Cold War"

''

Foreign Affairs

''Foreign Affairs'' is an American magazine of international relations and U.S. foreign policy published by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, membership organization and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and ...

'', Vol. 46, No. 1, October 1967."Against Academic Apartheid"

'' The Social Contract'', Vol. 1, No. 1, Inaugural Issue, Fall 1990.

Books

*193''Orestes A. Brownson: A Pilgrim's Progress''

*194

''The Age of Jackson''

*1949 '' The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom'' *1950 ''What About Communism?'' *1951 ''The General and the President, and the Future of American Foreign Policy'' *195

''The Crisis of the Old Order: 1919–1933'' (''The Age of Roosevelt'', Vol. I)

*195

''The Coming of the New Deal: 1933–1935'' (''The Age of Roosevelt'', Vol. II)

*196

''The Politics of Upheaval: 1935–1936'' (''The Age of Roosevelt'', Vol. III)

*1960 ''Kennedy or Nixon: Does It Make Any Difference?'' *196

''The Politics of Hope''

*1963 ''Paths of American Thought'' (ed. with Morton White) *1965 '' A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House'' *1965 ''The MacArthur Controversy and American Foreign Policy'' *196

''The Bitter Heritage: Vietnam and American Democracy, 1941–1966''

*1967 ''Congress and the Presidency: Their Role in Modern Times'' *196

''Violence: America in the Sixties''

*1969 ''The Crisis of Confidence: Ideas, Power, and Violence in America'' *197

''The Origins of the Cold War''

*1973 '' The Imperial Presidency'' – reissued in 1989 (with epilogue) and 2004 *197

''Robert Kennedy and His Times''

– adapted into a 1985 TV miniseries *1983 ''Creativity in Statecraft'' *1983 ''

The Almanac of American History

''The Almanac of American History'' (1983) (revised edition 2004) is a reference work on American history in chronology format. Its general editor is Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., and the executive editor is John S. Bowman.

Schlesinger wrote the ...

'' – revised edition, 2004

*1986 ''The Cycles of American History''

*1988 ''JFK Remembered''

*1988 ''War and the Constitution: Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt''

*1988 ''Cleopatra'', New York: Chelsea House, ( Hoobler, Dorothy; Hoobler, Thomas; introductory essay "On leadership" by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. )

*1990 ''Is the Cold War Over?''

*1991 '' The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society''

*2000 ''20th Century Day by Day: 100 Years Of News From January 1, 1900, to December 31, 1999''

*2000 ''A Life in the 20th Century, Innocent Beginnings, 1917–1950''

*2004 ''War and the American Presidency''

*200''Journals 1952–2000''

*2011 ''Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life With John F Kennedy'' (Mrs. Kennedy's interview shortly after her husband's assassination) Besides writing biographies he also wrote a foreword to a book on Vladimir Putin which came out in 2003 under the same name and was published by

Chelsea House Publishers

Infobase Publishing is an American publisher of reference book titles and textbooks geared towards the North American library, secondary school, and university-level curriculum markets. Infobase operates a number of prominent imprints, including ...

.

Schlesinger's papers will be available at the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

.

Awards

*1946 Pulitzer Prize for History – ''The Age of Jackson'' *1955 Elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences *1958 Bancroft Prize – ''The Crisis of the Old Order'' *1958 Francis Parkman Prize – ''The Crisis of the Old Order'' *1966 National Book Award in History and Biography – ''A Thousand Days'' *1966 Pulitzer Prize for Biography – ''A Thousand Days'' *1978 Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement *1979 National Book Award in Biography – ''Robert Kennedy and His Times'' *1987 Elected member of the American Philosophical Society *1998 National Humanities Medal *2003Four Freedoms Award

The Four Freedoms Award is an annual award presented to "those men and women whose achievements have demonstrated a commitment to those principles which United States, US President of the United States, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt proclaime ...

*2006 Paul Peck Award

*200Niebuhr Medal

Awarded by Elmhurst College to an individual who exemplifies the ideals of Reinhold and

H. Richard Niebuhr

Helmut Richard Niebuhr (September 3, 1894 – July 5, 1962) is considered one of the most important Christian theological ethicists in 20th-century America, best known for his 1951 book ''Christ and Culture'' and his posthumously published boo ...

. Schlesinger was greatly influenced by Reinhold Niebuhr.

Footnotes

Further reading

* Aldous, Richard. ''Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian'' (W.W. Norton, 2017online book review

* Diggins, John Patrick, ed. ''The Liberal Persuasion: Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and the Challenge of the American Past,'' Princeton UP, 1997

online free

*Feller, Daniel, "Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.," in Robert Allen Rutland, ed. ''Clio's Favorites: Leading Historians of the United States, 1945–2000'' U of Missouri Press, 2000; pp. 156–169. * Martin, John Bartlow. ''Adlai Stevenson of Illinois.'' New York: Doubleday. 1976. * Thomas Meaney, "The

Hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies migh ...

Factory" (review of Richard Aldous

Richard Aldous is a British historian and biographer.

Born in Essex, Aldous was educated at the University of Cambridge. In 2006 he was made head of school at the department of history and archives in UCD. Aldous wrote books about Malcolm Sarge ...

, ''Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian'', Norton, 486 pp., ), ''London Review of Books

The ''London Review of Books'' (''LRB'') is a British literary magazine published twice monthly that features articles and essays on fiction and non-fiction subjects, which are usually structured as book reviews.

History

The ''London Review of ...

'', vol. 40, no. 3 (8 February 2018), pp. 13–15. "Aldous has chosen an apt subtitle for his biography: Schlesinger was an 'imperial' historian in his willingness to take up the burden of the American empire's PR, though 'The Imperious Publicist' would have served just as well." (p. 14)

*Sue Saunders''Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.''

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum, February 15, 2006. * Wilentz, Sean, "The High Table Liberal" (review of

Richard Aldous

Richard Aldous is a British historian and biographer.

Born in Essex, Aldous was educated at the University of Cambridge. In 2006 he was made head of school at the department of history and archives in UCD. Aldous wrote books about Malcolm Sarge ...

, ''Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian'', Norton, 486 pp.), '' The New York Review of Books'', vol. LXV, no. 2 (8 February 2018), pp. 31–33. " e subtitle of Richard Aldous's otherwise solid biography is... erroneous. Arthur Schlesinger Jr. was in no way an 'imperial' historian; he was an anti-imperial historian." (p. 31)

Primary sources

*Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. ''A Thousand days: John F Kennedy in the White House''. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1965. *Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. ''A Life in the Twentieth Century: Innocent Beginnings, 1917–1950''. (2000), autobiography, vol 1. *Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. ''Journals: 1952–2000'' (2007)External links

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. papers 1922–2007

held by the Manuscripts and Archives Division,

New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

*

''In Depth'' interview with Schlesinger, December 3, 2000

* Eisler, Kim.

, ''Washingtonian'', March 6, 2008.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and "court philosopher" of the Kennedy administration was 89 when he died.

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. 1917 births 2007 deaths 20th-century American historians American male non-fiction writers 21st-century American historians 21st-century American male writers American cultural critics American people of Austrian descent American people of English descent American people of German-Jewish descent American Unitarians Cold War historians Critics of multiculturalism Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Historians of the United States Kennedy administration personnel Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters National Book Award winners National Humanities Medal recipients New York (state) Democrats People of the Office of Strategic Services People of the United States Office of War Information Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography winners Bancroft Prize winners Pulitzer Prize for History winners Phillips Exeter Academy alumni Harvard College alumni Harvard Fellows Harvard University faculty Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Social critics World War II spies for the United States The Century Foundation 20th-century American male writers Presidents of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Members of the American Philosophical Society