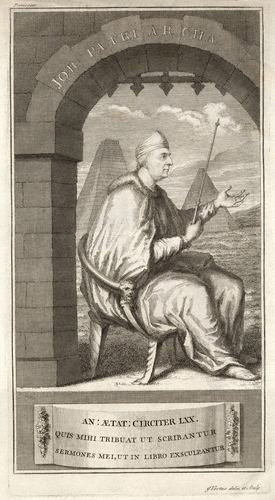

Samuel Wesley (poet, Died 1735) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Wesley (17 December 1662 – 25 April 1735) was a clergyman of the

The "Essay on Heroic Poetry", serving as Preface to ''The Life of Our Blessed Lord and Saviour'', reveals something of its author's erudition. Among the critics, he was familiar with

The "Essay on Heroic Poetry", serving as Preface to ''The Life of Our Blessed Lord and Saviour'', reveals something of its author's erudition. Among the critics, he was familiar with

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, a poet, and a writer. He was the father of John Wesley

John Wesley ( ; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a principal leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies ...

and Charles Wesley

Charles Wesley (18 December 1707 – 29 March 1788) was an English Anglican cleric and a principal leader of the Methodist movement. Wesley was a prolific hymnwriter who wrote over 6,500 hymns during his lifetime. His works include "And Can It ...

, the founders of Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

.

Family and early life

Samuel Wesley was the second son of Rev. John Westley or Wesley, rector of Winterborne Whitechurch,Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

. His mother was the daughter of John White, the rector of Trinity Church, Dorchester.

Following grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a Latin school, school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented Se ...

education in Dorchester, Wesley was sent away from home to prepare for ministerial training under Theophilus Gale. Gale's death in 1678 forestalled this plan. Instead, he attended another grammar school. After that, he studied at dissenting academies

The dissenting academies were schools, colleges and seminaries (often institutions with aspects of all three) run by English Dissenters, that is, Protestants who did not conform to the Church of England. They formed a significant part of educatio ...

under Edward Veel in Stepney

Stepney is an area in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London. Stepney is no longer officially defined, and is usually used to refer to a relatively small area. However, for much of its history the place name was applied to ...

and then Charles Morton in Newington Green

Newington Green is an open space in North London between Islington and Hackney. It gives its name to the surrounding area, roughly bounded by Ball's Pond Road to the south, Petherton Road to the west, Green Lanes and Matthias Road to the north, ...

, where Gale had lived. Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

also attended Morton's school. This school was situated "probably on the site of the current Unitarian church", contemporaneously with Wesley. Samuel resigned his place and his annual scholarship among the Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

. After that, he walked all the way to Oxford, where he enrolled at Exeter College as a "poor scholar". He functioned as a "servitor

In certain university, universities (including some Colleges of the University of Oxford, colleges of University of Oxford and the University of Edinburgh), a servitor was an undergraduate student who received free accommodation (and some free mea ...

", which means he sustained himself financially by waiting upon wealthy students. He also published a small book of poems, entitled ''Maggots: or Poems on Several Subjects never before Handled'' in 1685. The unusual title is explained in a few lines from the first page of the work:

Wesley married Susanna Annesley in 1688. He fathered, among others, Samuel (the younger), Mehetabel, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Charles Wesley

Charles Wesley (18 December 1707 – 29 March 1788) was an English Anglican cleric and a principal leader of the Methodist movement. Wesley was a prolific hymnwriter who wrote over 6,500 hymns during his lifetime. His works include "And Can It ...

. He had 19 children, nine of whom died in infancy. Three boys and seven girls survived.

In 1688 he became curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are as ...

at St. Botolph's, Aldersgate, London, serving there for about one year. In 1689 he was made chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

on a British Man-o-war. In 1690 he became curate at Newington Butts, Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

. Then, in 1691 the rector of South Ormsby, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

. By 1697 he was resident as rector of Epworth, Lincolnshire

Epworth is a market town and civil parish on the Isle of Axholme, in the North Lincolnshire unitary authority of Lincolnshire, England.OS Explorer Map 280: Isle of Axholme, Scunthorpe and Gainsborough: (1:25,000) : The town lies on the A161 ro ...

.

In 1697 he was appointed to the living at Epworth, Lincolnshire

Epworth is a market town and civil parish on the Isle of Axholme, in the North Lincolnshire unitary authority of Lincolnshire, England.OS Explorer Map 280: Isle of Axholme, Scunthorpe and Gainsborough: (1:25,000) : The town lies on the A161 ro ...

through the benevolence of Queen Mary. He may have come to the queen's attention because of his heroic poem, "The Life of Christ" (1693). He dedicated this poem to her. Wesley's high-church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, nd sacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although used in connection with various Christia ...

liturgies, academic proclivities, and loyalist Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

politics were a complete mismatch for some of his illiterate parishioners. He was not warmly received, and his ministry was not widely appreciated. Wesley was soon deep in debt and much of his life would be spent trying to make financial ends meet. In 1709 his parsonage

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of a given religion, serving as both a home and a base for the occupant's ministry. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, pa ...

was destroyed by fire, and his son John was barely rescued from the flames. The parsonage was rebuilt and is now known as the Old Rectory, Epworth.

Career

His poetic career began in 1685 with the publication of ''Maggots'', a collection of juvenile verses on trivial subjects, the preface to which apologizes to the reader because the book is neither grave nor gay. The poems appear to be an attempt to prove that poetic language can create beauty out of the most revolting subject. The first poem, "On a Maggot", is composed in hudibrastics, with a diction obviously Butlerian, and it is followed by facetious poetic dialogues and byPindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

ics of the Cowleian sort but on such subjects as "On the Grunting of a Hog". In 1688 Wesley took his B.A, at Exeter College, Oxford

Exeter College (in full: The Rector and Scholars of Exeter College in the University of Oxford) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, and the fourth-oldest college of the university.

The college was founde ...

, following which he became a naval chaplain and, in 1690, rector of South Ormsby. In 1694 he took his MA from Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Corpus Christi College (full name: "The College of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary", often shortened to "Corpus") is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. From the late 14th c ...

, and the following year he became rector of Epworth. During the run of the '' Athenian Gazette'' (1691–1697) he joined with Richard Sault and John Norris in assisting John Dunton, the promoter of the undertaking. His second venture in poetry, the ''Life of Our Blessed Lord and Saviour'', an epic largely in heroic couplets with a prefatory discourse on heroic poetry, appeared in 1693, was reissued in 1694, and was honoured with a second edition in 1697. In 1695 he dutifully came forward with ''Elegies'', lamenting the deaths of Queen Mary II and Archbishop Tillotson. The ''Epistle to a Friend Concerning Poetry'' (1700) was followed by at least four other volumes of verse, the last of which was issued in 1717. His poetry appears to have had readers on a certain level, but it stirred up little pleasure among wits, writers, or critics. Judith Drake confessed that she was lulled to sleep by Blackmore's ''Prince Arthur'' and by Wesley's "heroics" (''Essay in Defence of the Female Sex'', 1696, p. 50). And he was satirized as a mere poetaster

Poetaster (), like rhymester or versifier, is a derogatory term applied to bad or inferior poets. Specifically, ''poetaster'' has implications of unwarranted pretensions to artistic value. The word was coined in Latin by Erasmus in 1521. It was f ...

in Garth's ''Dispensary'', in Swift's ''The Battle of the Books'', and in the earliest issues of the '' Dunciad''.

Controversy

For a few years in the early eighteenth century, Wesley found himself in the vortex of controversy. Brought up in the dissenting tradition, he had swerved into conformity at some point during the 1680s, possibly under the influence of Tillotson, whom he greatly admired (cf. ''Epistle to a Friend'', pp. 5–6). In 1702 there appeared his ''Letter from a Country Divine to his friend in London concerning the education of dissenters in their private academies'', apparently written about 1693. This attack upon dissenting academies was published at an unfortunate time, when the public mind was inflamed by the intolerance of overzealous churchmen. Wesley was furiously answered; he replied in ''A Defence of a Letter'' (1704), and again in ''A Reply to Mr. Palmer's Vindication'' (1707). It is scarcely to Wesley's credit that in this quarrel he stood shoulder to shoulder with that most hot-headed of all contemporary bigots, Henry Sacheverell. His prominence in the controversy earned him the ironic compliments ofDaniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

, who recalled that our "Mighty Champion of this very High-Church Cause" had once written a poem to satirize frenzied Tories (''Review'', II, no. 87, 22 September 1705). About a week later, Defoe, having got wind of a collection being taken up for Wesley – who in consequence of a series of misfortunes was badly in debt – intimated that High-Church pamphleteering had turned out very profitably for both Lesley and Wesley (2 October 1705). But in such snarling and bickering Wesley was out of his element, and he seems to have avoided future quarrels.

His literary criticism is small in bulk. But though it is neither brilliant nor well written (Wesley apparently composed at a break-neck clip), it is not without interest. Pope observed in 1730 that he was a "learned" man (letter to Swift, in ''Works'', ed. Elwin-Courthope, VII, 184). The observation was correct, but it should be added that Wesley matured at the end of an age famous for its great learning, an age whose most distinguished poet was so much the scholar that he appeared more the pedant than the gentleman to critics of the succeeding era; Wesley was not singular for erudition among his seventeenth-century contemporaries.

"Essay on Heroic Poetry"

The "Essay on Heroic Poetry", serving as Preface to ''The Life of Our Blessed Lord and Saviour'', reveals something of its author's erudition. Among the critics, he was familiar with

The "Essay on Heroic Poetry", serving as Preface to ''The Life of Our Blessed Lord and Saviour'', reveals something of its author's erudition. Among the critics, he was familiar with Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC), Suetonius, Life of Horace commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). Th ...

, Longinus, Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus (,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary style was ''atticistic'' – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.

...

, Heinsius, Bochart, Balzac, Rapin, Le Bossu, and Boileau. But this barely hints at the extent of his learning. In the notes on the poem itself the author displays an interest in classical scholarship, Biblical commentary, ecclesiastical history, scientific inquiry, linguistics and philology, British antiquities, and research into the history, customs, architecture, and geography of the Holy Land; he shows, an intimate acquaintance with Grotius

Hugo Grotius ( ; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Hugo de Groot () or Huig de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, statesman, poet and playwright. A teenage prodigy, he was born in Delft an ...

, Henry Hammond

Henry Hammond (18 August 1605 – 25 April 1660) was an English churchman, church historian and theologian, who supported the Royalist cause during the English Civil War.

Early life

He was born at Chertsey in Surrey on 18 August 1605, the y ...

, Joseph Mede

Joseph Mede (1586 in Berden – 1639) was an English scholar with a wide range of interests. He was educated at Christ's College, Cambridge, where he became a Fellow in 1613. He is now remembered as a biblical scholar. He was also a naturalist ...

, Spanheim, Sherlock, Lightfoot, and Gregory, with Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; ; ; ), also called , was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

The only event in Philo's life that can be decisively dated is his representation of the Alexandrian J ...

, Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

, Fuller, Walker, Camden, and Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Society of Jesus, Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jes ...

; and he shows an equal readiness to draw upon Ralph Cudworth

Ralph Cudworth (; 1617 – 26 June 1688) was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian Hebraist, classicist, theologian and philosopher, and a leading figure among the Cambridge Platonists who became 11th Regius Professor of Hebrew (Cambr ...

's ''True Intellectual System'' and Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

's new theories concerning the nature of light. In view of such a breadth of knowledge it is somewhat surprising to find him quoting as extensively as he does in the "Essay" from Le Bossu and Rapin, and apparently leaning heavily upon them.

The "Essay" was composed at a time when the prestige of Rymer and neo-Aristotelianism in England was already declining, and though Wesley expressed some admiration for Rapin and Le Bossu, he is by no means docile under their authority. Whatever the weight of authority, he says, "I see no cause why Poetry should not be brought to the Test f reason as well as Divinity...." As to the sacred example of Homer, who based his great epic on mythology, Wesley remarks, "But this ythologybeing now antiquated, I cannot think we are oblig'd superstitiously to follow his Example, any more than to make Horses speak, as he does that of Achilles." To the question of the formidable Boileau, "What Pleasure can it be to hear the howlings of repining Lucifer?" our critic responds flippantly, "I think 'tis easier to answer than to find out what shew of Reason he had for asking it, or why Lucifer mayn't howl as pleasantly as either Cerberus, or Knoeladus." Without hesitation or apology he takes issue with Rapin's conception of Decorum in the epic. But Wesley is empiricist as well as rationalist, and the judgment of authority can be upset by appeal to the court of experience. To Balzac's suggestion that, to avoid difficult and local proper names in poetry, generalized terms be used, such as ''Ill-luck'' for the ''Fates'' and the ''Foul Fiend'' for ''Lucifer'', our critic replies with jaunty irony, "... and whether this wou'd not sound extremely Heroical, I leave any Man to judge", and thus he dismisses the matter. Similarly, when Rapin objects to Tasso's mingling of lyric softness in the majesty of the epic, Wesley points out sharply that no man of taste will part with the fine scenes of tender love in Tasso, Dryden, Ovid, Ariosto, and Spenser "for the sake of a fancied Regularity". He had set out to defend the Biblical epic, the Christian epic, and the propriety of Christian machines in epic, and no rules or authority could deter him. As good an example as any of his independence of mind can be seen in a note on Bk. I, apropos of the poet's use of obsolete words (''Life of Our Blessed Lord'', 1697, p. 27): It may be in vicious imitation of Milton and Spenser, he says in effect, but I have a fondness for old words, they please my ear, and that is all the reason I can give for employing them.

Wesley's resistance to a strict application of authority and the rules grew partly out of the rationalistic and empirical temper of Englishmen in his age, but it also sprang from his learning. From various sources he drew the theory that Greek and Latin were but corrupted forms of ancient Phoenician, and that the degeneracy of Greek and Latin in turn had produced all, or most, of the present European tongues (''ibid.'', p. 354). In addition, he believed that the Greeks had derived some of their thought from older civilizations, and specifically that Plato had received many of his notions from the Jews (''ibid''., p. 230)—an idea which recalls the argument that Dryden in ''Religio Laioi'' had employed against the deists, furthermore, he had, like many of his learned contemporaries, a profound respect for Hebrew culture and the sublimity of the Hebrew scriptures, going so far as to remark in the "Essay on Heroic Poetry" that "most, even of he heathen poets'beat Fancies and Images, as well as Names, were borrow'd from the Antient Hebrew Poetry and Divinity." In short, however faulty his particular conclusions, he had arrived at an historical viewpoint, from which it was no longer possible to regard the classical standards—much less the standards of French critics—as having the holy sanction of Nature herself.

Literary tastes

Some light is shed on the literary tastes of his period by the ''Epistle to a Friend Concerning Poetry'' (1700) and the ''Essay on Heroic Poetry'' (1697), which with a few exceptions were in accord with the prevailing current. ''The Life of Our Blessed Lord'' shows strongly the influence of Cowley's ''Davideis''. Wesley's great admiration persisted after the tide had turned away from Cowley; and his liking for the "divine Herbert" and for Crashaw represented the tastes of sober and unfashionable readers. Although he professed unbounded admiration for Homer as the greatest genius in nature, in practice he seemed more inclined to follow the lead of Cowley, Virgil, and Vida. Although there was much in Ariosto that he enjoyed, he preferred Tasso; the irregularities in both, however, he felt bound to deplore. To Spenser's ''Faerie Queene

''The Faerie Queene'' is an English Epic poetry, epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books IIII were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IVVI. ''The Faerie Queene'' is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and ov ...

'' he allowed extraordinary merit. If the plan of it was noble, he thought, and the mark of a comprehensive genius, yet the action of the poem seemed confused. Nevertheless, like Prior later, Wesley was inclined to suspend judgment on this point because the poem had been left incomplete. To Spenser's "thoughts" he paid the highest tribute, and to his "Expressions flowing natural and easie, with such a prodigious Poetical Copia as never any other must expect to enjoy." Like most of the Augustans Wesley did not care greatly for '' Paradise Regained'', but he partly atoned by his praise for ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an Epic poetry, epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The poem concerns the Bible, biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their ex ...

'', which was an "original" and therefore "above the common Rules". Though defective in its action, it was resplendent with sublime thoughts perhaps superior to any in Virgil or Homer, and full of incomparable and exquisitely moving passages. In spite of his belief that Milton's blank verse was a mistake, making for looseness and incorrectness, he borrowed lines and images from it, and in Bk. IV of ''The Life of Our Blessed Lord'' he incorporated a whole passage of Milton's blank verse in the midst of his heroic couplets.

Wesley's attitude toward Dryden deserves a moment's pause. In the "Essay on Heroic Poetry" he observed that a speech of Satan's in ''Paradise Lost'' is nearly equalled in Dryden's ''State of Innocence''. Later in the same essay he credited a passage in Dryden's ''King Arthur'' with showing an improvement upon Tasso. There is no doubt as to his vast respect for the greatest living poet, but his remarks do not indicate that he ranked Dryden with Virgil, Tasso, or Milton; for he recognized as well as we that the power to embellish and to imitate successfully does not constitute the highest excellence in poetry. In the ''Epistle to a Friend'' he affirmed his admiration for Dryden's matchless style, his harmony, his lofty strains, his youthful fire, and even his wit—in the main, qualities of style and expression. But by 1700 Wesley had absorbed enough of the new puritanism that was rising in England to qualify his praise; now he deprecated the looseness and indecency of the poetry, and called upon the poet to repent. One other point calls for comment. Wesley's scheme for Christian machinery in the epic, as described in the "Essay on Heroic Poetry", is remarkably similar to Dryden's. Dryden's had appeared in the essay on satire prefaced to his translation of Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ; 55–128), was a Roman poet. He is the author of the '' Satires'', a collection of satirical poems. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, but references in his works to people f ...

, published late in October 1692; Wesley's scheme appeared soon after June 1693.

The ''Epistle to a Friend Concerning Poetry'' is neither startling nor contemptible; it has, in fact, much more to say than the rhymed treatises on verse by Roscommon and Mulgrave. Its remarks on Genius are fresh, though tantalizing in their brevity, and it defends the Moderns with both neatness and energy. Much of its advice is cautious and commonplace—but such was the tradition of the poetical treatise on verse. Appearing within two years of Collier's first attack upon the stage, it reinforces some of that worthy's contentions, but we are not aware of its having had much effect.

Theology

Samuel Wesley held Anglican Arminianist views. TheArminian

Arminianism is a movement of Protestantism initiated in the early 17th century, based on the Christian theology, theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed Church, Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius and his historic supporters known as Remo ...

Hugo Grotius, was his favourite biblical commentator. Through his sermons, he demonstrated beliefs in the tenets of Arminianism and especially in its distinctive prevenient grace

Prevenient grace (or preceding grace or enabling grace) is a Christian theological concept that refers to the grace of God in a person's life which precedes and prepares to conversion. The concept was first developed by Augustine of Hippo (354 ...

.

See also

*Charles Wesley

Charles Wesley (18 December 1707 – 29 March 1788) was an English Anglican cleric and a principal leader of the Methodist movement. Wesley was a prolific hymnwriter who wrote over 6,500 hymns during his lifetime. His works include "And Can It ...

* John Wesley

John Wesley ( ; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a principal leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies ...

Notes and references

This material was originally from the introduction of Augustan Reprint Society's edition of ''An Epistle to a Friend Concerning Poetry'' (1700) and the ''Essay on Heroic Poetry'' (second edition, 1697)'', volume 5 in the Augustan Reprint series, part of series 2, Essay on Poetry: No. 2, first printed in 1947. It was written by Edward Niles Hooker. It was published in the US without acopyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive legal right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, ...

notice, which at the time meant it fell into the public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no Exclusive exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly Waiver, waived, or may be inapplicable. Because no one holds ...

.

Citations

Sources

* * * *External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wesley, Samuel 01 1662 births 1735 deaths 17th-century Christian clergy 17th-century English poets 17th-century English male writers 18th-century British Christian clergy 18th-century English poets 18th-century English male writers Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford Arminian ministers Arminian writers Burials in Lincolnshire English Christian religious leaders English male non-fiction writers English male poets English military chaplains English non-fiction writers Royal Navy chaplainsSamuel

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venera ...

British poets