Robin Hyde on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

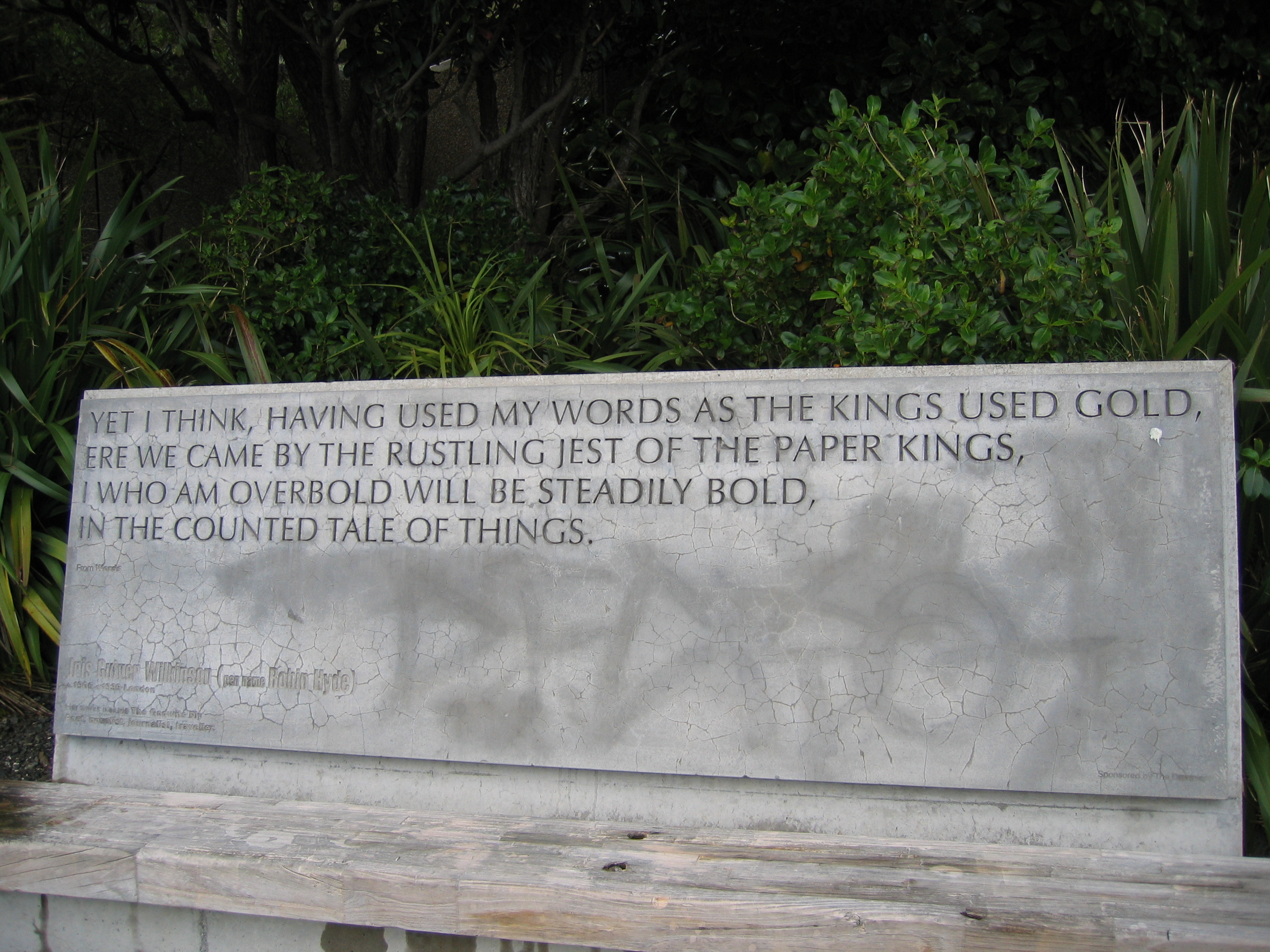

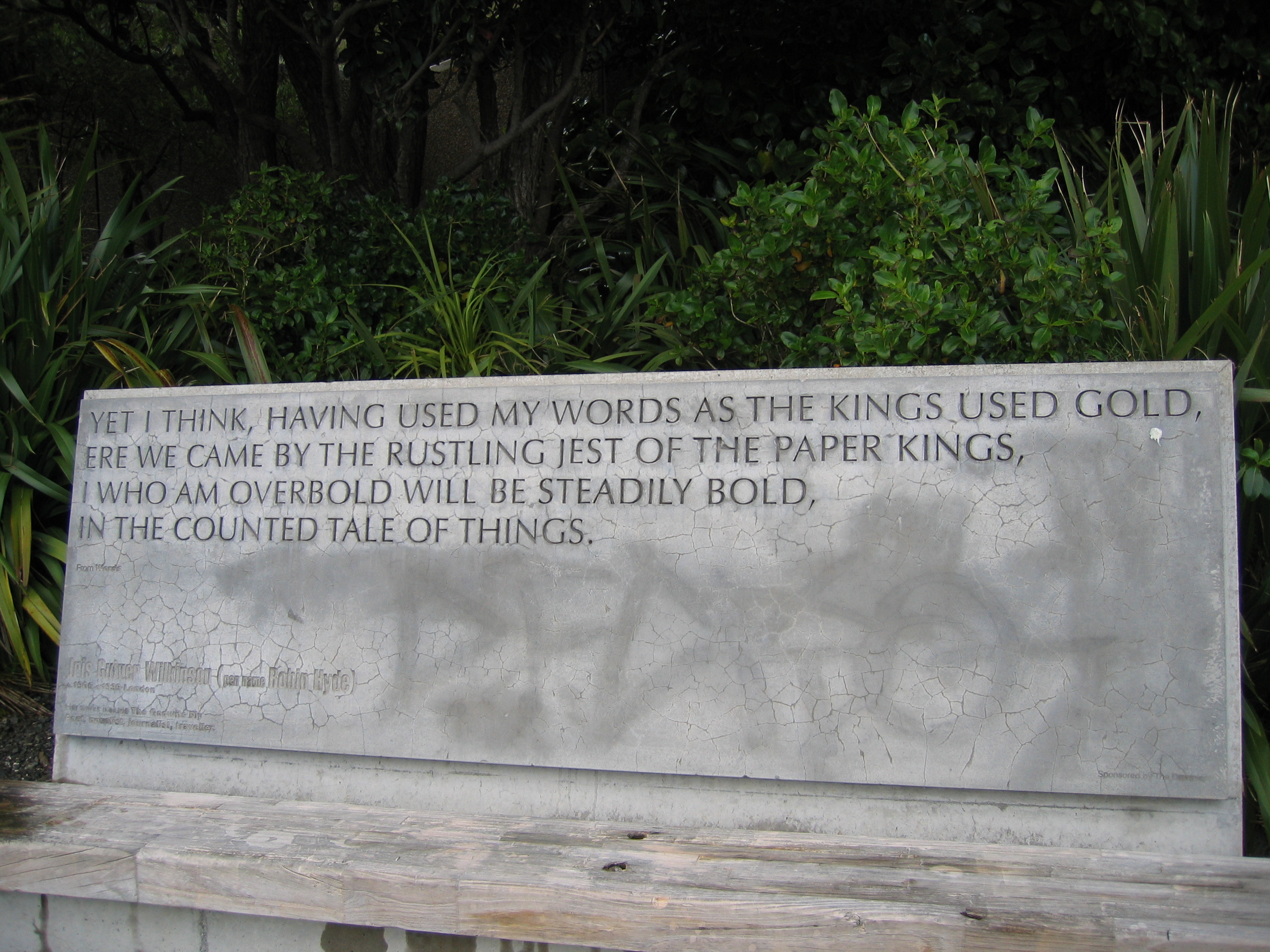

Robin Hyde, the pseudonym used by Iris Guiver Wilkinson (19 January 1906 – 23 August 1939), was a

Robin Hyde, the pseudonym used by Iris Guiver Wilkinson (19 January 1906 – 23 August 1939), was a

]

]

Profile from ''The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature''

at the New Zealand Book Council

New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre: Online works and articles

* ttp://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-PopKowh-t1-body-d12.html Poems in ''Kowhai Gold'' (1930)

Te Ara: 1966 article from ''An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand''Robin Hyde in China

at the NZEPC, Auckland University

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hyde, Robin 1906 births 1939 deaths 1939 suicides 20th-century New Zealand novelists 20th-century New Zealand poets 20th-century New Zealand journalists 20th-century New Zealand women writers New Zealand women poets New Zealand women novelists New Zealand people of English descent South African emigrants to New Zealand People educated at Wellington Girls' College Victoria University of Wellington alumni New Zealand autobiographers Women autobiographers Suicides in Kensington Drug-related suicides in England

Robin Hyde, the pseudonym used by Iris Guiver Wilkinson (19 January 1906 – 23 August 1939), was a

Robin Hyde, the pseudonym used by Iris Guiver Wilkinson (19 January 1906 – 23 August 1939), was a South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

n-born New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

poet, journalist and novelist.

Early life

Wilkinson was born inCape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

to an English father and an Australian mother, and was taken to Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

before her first birthday. She had her secondary education at Wellington Girls' College

Wellington Girls' College was founded in 1883 in Wellington, New Zealand. At that time it was called Wellington Girls' High School. Wellington Girls' College is a year 9 to 13 state secondary school, located in Thorndon in central Wellington.

H ...

, where she wrote poetry and short stories for the school magazine. After school she briefly attended Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington ( mi, Te Herenga Waka) is a university in Wellington, New Zealand. It was established in 1897 by Act of Parliament, and was a constituent college of the University of New Zealand.

The university is well know ...

. When she was 18, Hyde suffered a knee injury which required a hospital operation. Lameness and pain haunted her for the rest of her life. In 1925 she became a journalist for Wellington's ''Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

'' newspaper, mostly writing for the women's pages. She continued to support herself through journalism throughout her life.

Later life

While working at the ''Dominion'', she had a brief love affair with Harry Sweetman, who left her to travel to England. In 1926, in Rotorua for a holiday and treatment for her tubercular knee, Hyde had an affair with Frederick de Mulford Hyde. When Hyde fell pregnant, Frederick paid for her to have the child inSydney, Australia

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and List of cities in Oceania by population, Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metro ...

. Their son, Christopher Robin Hyde, was stillborn. She was to adopt the name 'Robin Hyde' as a 'nom de guerre', to preserve his memory. On her return to New Zealand in December 1926, she discovered that Frederick had married. Traumatised by the loss of her child, Hyde was hospitalised at Queen Mary Hospital in Hanmer Springs

Hanmer Springs is a small town in the Canterbury region of the South Island of New Zealand. The Māori name for Hanmer Springs is Te Whakatakanga o te Ngārahu o te ahi a Tamatea, which means “where the ashes of Tamate’s (sic) fire lay� ...

and then cared for at the family home in Wellington, though only her mother knew of the pregnancy.

After a period of recovery, she began to write again, publishing poetry in several New Zealand newspapers in 1927. She was also engaged to write columns for the Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River / ...

''Sun'', and the ''Mirror''. However, she became frustrated at the lack of creative input, as the papers merely wanted a social column. Social columns or women's pages were the main outlet available to women journalists during the period. These experiences contributed to her treatise on journalism in New Zealand, ''Journalese'', published in 1934.

In 1930, while working for the ''Wanganui Chronicle'', Hyde had an affair with the Marton-based journalist Harry Lawson Smith. Their son, Derek Arden Challis, was born in Picton that October. Lawson Smith was married, and his only relationship with Hyde and their son was to provide sporadic maintenance payments. In time Hyde's mother learned of Derek's existence, but her father was never told.

In 1929 Hyde published her first book of poetry, ''The Desolate Star''. Between 1935 and 1938 she published five novels: ''Passport to Hell'' (1936), ''Check To Your King'' (1936), ''Wednesday's Children'' (1937), ''Nor the Years Condemn'' (1938), and ''The Godwits Fly'' (1938). A manuscript of her unpublished autobiography was given to Auckland Libraries

Auckland Libraries is the public library system for the Auckland Region of New Zealand. It was created when the seven separate councils in the Auckland region merged in 2010. It is currently the largest public-library network in the Southern He ...

by Dr Gilbert Tothill.

]

]

Final years and death

In early 1938 she left New Zealand and travelled toHong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

, arriving in early February. At the time, much of eastern China was under Japanese occupation, after the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

. Hyde was meant to travel to Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whic ...

then Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

to take the trans-Siberian railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

to Europe. When the connection was delayed she made her way to Japanese-occupied Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

, where she met fellow New Zealander Rewi Alley

Rewi Alley (known in China as 路易•艾黎, Lùyì Àilí, 2 December 1897 – 27 December 1987) was a New Zealand-born writer and political activist. A member of the Chinese Communist Party, he dedicated 60 years of his life to the cause a ...

. Various peregrinations through China followed, including Canton and Hankow

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers whe ...

, the latter of which was the centre of Chinese resistance to Japanese occupation. She moved north to visit the battlefront and was in Hsuchow when Japanese forces took the city on 19 May.

Hyde attempted to flee the area by walking along the railway lines and was eventually escorted by Japanese officials to the port city of Tsing Tao where she was handed over to British authorities. Shortly after she resumed her journey to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

via sea, arriving in Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

on 18 September 1938. She died by her own hand with an overdose of Benzedrine

Amphetamine (contracted from alpha- methylphenethylamine) is a strong central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, and obesity. It is also commonly used a ...

at 1 Pembridge Square, Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West End of London, West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up b ...

, a boarding house where she had been living.''Journal of New Zealand Literature'', Issues 15-17 (1997), p. 25 She was survived by a son, Derek Challis, and was buried in the Kensington New Cemetery, at Gunnersbury

Gunnersbury is an area of West London, England.

Toponymy

The name "Gunnersbury" means "Manor house of a woman called Gunnhildr", and is from an old Scandinavian personal name + Middle English -''bury'', manor or manor house.

Development

Gunne ...

.

References

External links

*Profile from ''The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature''

at the New Zealand Book Council

New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre: Online works and articles

* ttp://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-PopKowh-t1-body-d12.html Poems in ''Kowhai Gold'' (1930)

Te Ara: 1966 article from ''An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand''

at the NZEPC, Auckland University

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hyde, Robin 1906 births 1939 deaths 1939 suicides 20th-century New Zealand novelists 20th-century New Zealand poets 20th-century New Zealand journalists 20th-century New Zealand women writers New Zealand women poets New Zealand women novelists New Zealand people of English descent South African emigrants to New Zealand People educated at Wellington Girls' College Victoria University of Wellington alumni New Zealand autobiographers Women autobiographers Suicides in Kensington Drug-related suicides in England