Reza Shah Pahlavi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

,

, spouse = Maryam Savadkoohi

Tadj ol-Molouk Ayromlu (queen consort)

Princess Shams

Princess Ashraf

Prince Ali Reza

Prince Gholam Reza

Prince Abdul Reza

Prince Ahmad Reza

Prince Mahmoud Reza

Princess Fatemeh

Prince Hamid Reza , house = Pahlavi , father = Abbas-Ali Khan , mother = Noush-Afarin , religion = , birth_date = , birth_place =

, module =

Reza Shah Pahlavi ( fa, رضا شاه پهلوی; ; originally Reza Khan (); 15 March 1878 – 26 July 1944) was an Iranian

, module =

Reza Shah Pahlavi ( fa, رضا شاه پهلوی; ; originally Reza Khan (); 15 March 1878 – 26 July 1944) was an Iranian

Reza Shah Pahlavi was born in the town of

Reza Shah Pahlavi was born in the town of

In the aftermath of the

In the aftermath of the  On 14 January 1921, the commander of the British Forces in Iran, General Edmund "Tiny" Ironside, promoted Reza Khan, who had been leading the Tabriz battalion, to lead the entire brigade. About a month later, under British direction, Reza Khan led his 3,000-4,000 strong detachment of the Cossack Brigade, based in Niyarak, Qazvin, and Hamadan, to Tehran and seized the capital. He forced the dissolution of the previous government and demanded that Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabaee be appointed Prime Minister. para. 2, 3 Reza Khan's first role in the new government was as commander of the Iranian Army, which he combined with the post of

On 14 January 1921, the commander of the British Forces in Iran, General Edmund "Tiny" Ironside, promoted Reza Khan, who had been leading the Tabriz battalion, to lead the entire brigade. About a month later, under British direction, Reza Khan led his 3,000-4,000 strong detachment of the Cossack Brigade, based in Niyarak, Qazvin, and Hamadan, to Tehran and seized the capital. He forced the dissolution of the previous government and demanded that Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabaee be appointed Prime Minister. para. 2, 3 Reza Khan's first role in the new government was as commander of the Iranian Army, which he combined with the post of

From the beginning of the appointment of Reza Khan as the minister of war, there was ever increasing tension with

From the beginning of the appointment of Reza Khan as the minister of war, there was ever increasing tension with

While the Shah left behind no major thesis, or speeches giving an overarching policy, his reforms indicated a striving for an Iran which—according to scholar

While the Shah left behind no major thesis, or speeches giving an overarching policy, his reforms indicated a striving for an Iran which—according to scholar

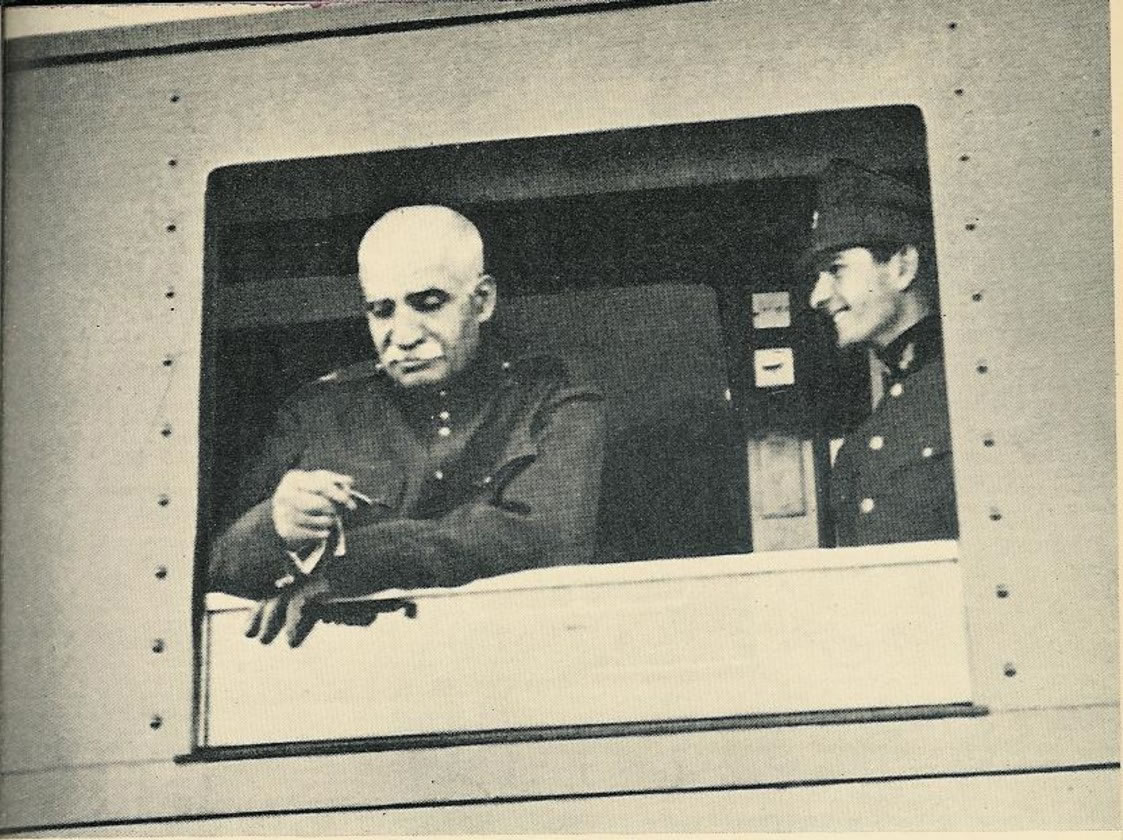

During Reza Shah's sixteen years of rule, major developments, such as large road construction projects and the

During Reza Shah's sixteen years of rule, major developments, such as large road construction projects and the  Along with the modernization of the nation, Reza Shah was the ruler during the time of the Women's Awakening (1936–1941). This movement sought the elimination of the

Along with the modernization of the nation, Reza Shah was the ruler during the time of the Women's Awakening (1936–1941). This movement sought the elimination of the

Parliamentary elections during the Shah's reign were not democratic. The general practice was to "draw up, with the help of the police chief, a list of parliamentary candidates for the interior minister. The interior minister then passed the same names onto the provincial governor-general. ... hohanded down the list to the supervisory electoral councils that were packed by the Interior Ministry to oversee the ballots. Parliament ceased to be a meaningful institution, and instead became a decorative garb covering the nakedness of military rule."

Reza Shah discredited and eliminated a number of his ministers. His minister of Imperial Court,

Parliamentary elections during the Shah's reign were not democratic. The general practice was to "draw up, with the help of the police chief, a list of parliamentary candidates for the interior minister. The interior minister then passed the same names onto the provincial governor-general. ... hohanded down the list to the supervisory electoral councils that were packed by the Interior Ministry to oversee the ballots. Parliament ceased to be a meaningful institution, and instead became a decorative garb covering the nakedness of military rule."

Reza Shah discredited and eliminated a number of his ministers. His minister of Imperial Court,

In the

In the

Persia or Iran, Persian or Farsi

, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) Although (internally) the country had been referred to as Iran throughout much of its history since the

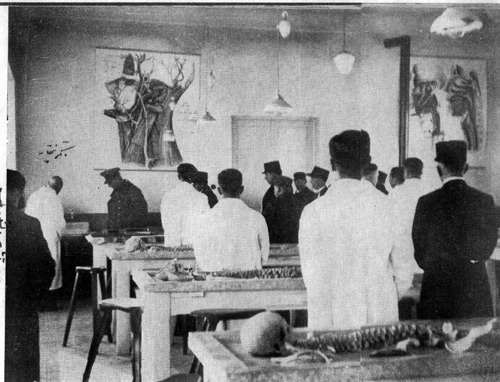

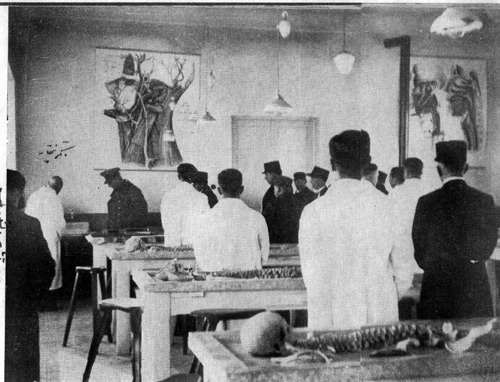

The devout were also angered by policies that allowed mixing of the sexes. Women were allowed to study in the colleges of law and medicine, and in 1934 a law set heavy fines for cinemas, restaurant, and hotels that did not open their doors to both sexes. Doctors were permitted to dissect human bodies. He restricted public mourning observances to one day and required mosques to use chairs instead of the traditional sitting on the floors of mosques.

By the mid-1930s, Reza Shah's rule had caused intense dissatisfaction of the

The devout were also angered by policies that allowed mixing of the sexes. Women were allowed to study in the colleges of law and medicine, and in 1934 a law set heavy fines for cinemas, restaurant, and hotels that did not open their doors to both sexes. Doctors were permitted to dissect human bodies. He restricted public mourning observances to one day and required mosques to use chairs instead of the traditional sitting on the floors of mosques.

By the mid-1930s, Reza Shah's rule had caused intense dissatisfaction of the

Reza Shah initiated change in foreign affairs as well. He worked to balance British influence with other foreigners and generally to diminish foreign influence in Iran.

One of the first acts of the new government after the 1921 entrance into Tehran was to tear up the treaty with the

Reza Shah initiated change in foreign affairs as well. He worked to balance British influence with other foreigners and generally to diminish foreign influence in Iran.

One of the first acts of the new government after the 1921 entrance into Tehran was to tear up the treaty with the

British government

In his campaign against foreign influence, he annulled the 19th-century capitulations to Europeans in 1928. Under these, Europeans in Iran had enjoyed the privilege of being subject to their own consular courts rather than to the Iranian judiciary. The right to print money was moved from the British Imperial Bank to his National Bank of Iran (Bank-i Melli Iran), as was the administration of the telegraph system, from the

In his campaign against foreign influence, he annulled the 19th-century capitulations to Europeans in 1928. Under these, Europeans in Iran had enjoyed the privilege of being subject to their own consular courts rather than to the Iranian judiciary. The right to print money was moved from the British Imperial Bank to his National Bank of Iran (Bank-i Melli Iran), as was the administration of the telegraph system, from the

The Shah's reign is sometimes divided into periods. All the worthwhile efforts of Reza Shah's reign were either completed or conceived in the 1925–1938 period, a period during which he required the assistance of reformists to gain the requisite legitimacy to consolidate this modern reign. In particular, Abdolhossein

The Shah's reign is sometimes divided into periods. All the worthwhile efforts of Reza Shah's reign were either completed or conceived in the 1925–1938 period, a period during which he required the assistance of reformists to gain the requisite legitimacy to consolidate this modern reign. In particular, Abdolhossein  Reza Shah attempted to forge a regional alliance with Iran's Middle Eastern neighbors, particularly

Reza Shah attempted to forge a regional alliance with Iran's Middle Eastern neighbors, particularly

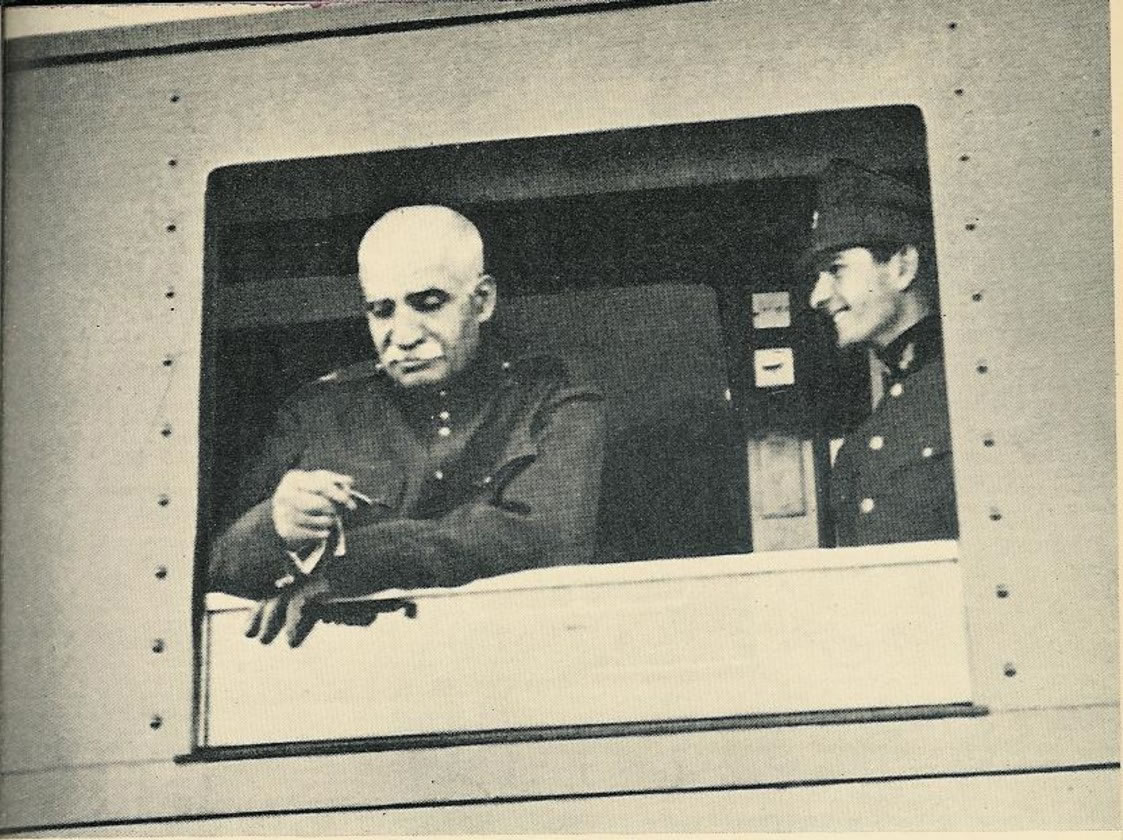

In August 1941 the Allied powers, the

In August 1941 the Allied powers, the  The Shah ordered pro-British

The Shah ordered pro-British  Reza Shah was forced by the invading British to

Reza Shah was forced by the invading British to

Like his son after him, Reza Shah died in exile. After the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union invaded and occupied Iran on 25 August 1941, the British offered to keep his family in power if Reza Shah agreed to a life of exile. Reza Shah abdicated and the British forces quickly took him and his children to

Like his son after him, Reza Shah died in exile. After the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union invaded and occupied Iran on 25 August 1941, the British offered to keep his family in power if Reza Shah agreed to a life of exile. Reza Shah abdicated and the British forces quickly took him and his children to

12 December 2010 He was sixty-six years old at the time of his death. After his death, his body was carried to

Satellite map

The Iranian parliament (Majlis) later designated the title "the Great" to be added to his name. On 14 January 1979, shortly before the

Under Reza Shah's reign, a number of new concepts were introduced between 1923 and 1941. Some of these significant changes, achievements, concepts and laws included:

* Successful suppression of separatist movements and reunification of Iran under a powerful central government.

* Foundation of the first

Under Reza Shah's reign, a number of new concepts were introduced between 1923 and 1941. Some of these significant changes, achievements, concepts and laws included:

* Successful suppression of separatist movements and reunification of Iran under a powerful central government.

* Foundation of the first

Reza Shah married, for the first time, Maryam Savadkoohi, who was his cousin, in 1894. The marriage lasted until Maryam's death in 1904, the couple had a daughter:

* Princess

Reza Shah married, for the first time, Maryam Savadkoohi, who was his cousin, in 1894. The marriage lasted until Maryam's death in 1904, the couple had a daughter:

* Princess

IRANNOTES.com , High Quality IRANIAN Banknotes and Coins

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Shah, Reza People of Pahlavi Iran 1878 births 1944 deaths 20th-century monarchs of Persia 20th-century Iranian people People from Mazandaran Province Commanders-in-Chief of Iran Critics of Islamism Critics of religions Iranian anti-communists Iranian nationalists Iranian secularists Leaders who took power by coup Mazandarani people Prime Ministers of Iran World War II political leaders Monarchs who abdicated Collars of the Order of the White Lion People from Savadkuh Imperial Iranian Army brigadier generals Exiled politicians People exiled to Mauritius Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland)

Tadj ol-Molouk Ayromlu (queen consort)

Turan Amirsoleimani

Turan Amirsoleimani ( fa, توران امیرسلیمانی, born Qamar ol-Molouk Amirsoleimani, (); 4 February 1905 – 24 July 1995) was an Iranian royal and the third wife of Reza Shah, with whom she had a son named Gholam Reza Pahlavi.

Biograp ...

Esmat Dowlatshahi

Esmat Dowlatshahi ( fa, عصمتالملوک دولتشاهی; 1905 – 25 July 1995) was an Iranian royal and the fourth and last wife of Reza Shah.

Early life

Dowlatshahi was born in 1905. She was a member of the Qajar dynasty. Her father w ...

, issue = Princess HamdamsaltanehPrincess Shams

Mohammad Reza Shah

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi ( fa, محمدرضا پهلوی, ; 26 October 1919 – 27 July 1980), also known as Mohammad Reza Shah (), was the last ''Shah'' (King) of the Imperial State of Iran from 16 September 1941 until his overthrow in the Irani ...

Princess Ashraf

Prince Ali Reza

Prince Gholam Reza

Prince Abdul Reza

Prince Ahmad Reza

Prince Mahmoud Reza

Princess Fatemeh

Prince Hamid Reza , house = Pahlavi , father = Abbas-Ali Khan , mother = Noush-Afarin , religion = , birth_date = , birth_place =

Alasht

Alasht ( fa, آلاشت, ', meaning ''Eagle Sanctuary'', also Romanized as Ālāsht) is a city in the Central District of Savadkuh County, Mazandaran Province, Iran. At the 2016 census, its population was 1,193.

Alasht is isolated by surroundin ...

, Savadkuh

Savadkuh County ( fa, شهرستان سوادكوه, ''Ŝahrestāne Sawādkuh''; also Savadkooh and Savadkouh) is located in Mazandaran province, Iran. The capital of the county is Pol Sefid. At the 2006 census, the county's population (includi ...

, Mazandaran, Sublime State of Persia

, death_date =

, death_place = Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

, Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

, burial_place = 7 May 1950Mausoleum of Reza Shah

The mausoleum of Reza Shah ( fa, آرامگاه رضاشاه), located in Ray south of Tehran, was the burial ground of Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878–1944), the penultimate ''Shahanshah'' (Emperor) of Iran. It was built close to Shah-Abdol-Azim sh ...

, Shah Abdol-Azim Shrine

The Shāh Abdol-Azīm Shrine ( fa, شاه عبدالعظیم), also known as Shabdolazim, located in Rey, Iran, contains the tomb of ‘Abdul ‘Adhīm ibn ‘Abdillāh al-Hasanī (aka Shah Abdol Azim). Shah Abdol Azim was a fifth generation de ...

, Rey

, signature = military officer

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent context ...

, politician (who served as minister of war

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

and prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

), and first shah

Shah (; fa, شاه, , ) is a royal title that was historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies.Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) It was also used by a variety of ...

of the House of Pahlavi

The Pahlavi dynasty ( fa, دودمان پهلوی) was the last Iranian royal dynasty, ruling for almost 54 years between 1925 and 1979. The dynasty was founded by Reza Shah Pahlavi, a non-aristocratic Mazanderani soldier in modern times, who ...

of the Imperial State of Iran

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas

...

and father of the last shah of Iran. He reigned from 15 December 1925 until he was forced to abdicate

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

by the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran on 16 September 1941. Reza Shah introduced many social, economic, and political reforms during his reign, ultimately laying the foundation of the modern Iranian state. Therefore, he is regarded as the founder of modern Iran.

At the age of 14 he joined the Iranian Cossack Brigade, and also served in the army. In 1911, he was promoted to first lieutenant, by 1912 he was elevated to the rank of captain and by 1915 he became a colonel. In February 1921, as leader of the entire Cossack Brigade based in Qazvin, he marched towards Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

and seized the capital. He forced the dissolution of the government and installed Zia ol Din Tabatabaee

Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabataba'i (June 1889 – 29 August 1969; fa, سید ضیاءالدین طباطبایی) was an Iranian journalist and politician who, with the help of Reza Shah, Reza Khan Savadkuhi, led the 1921 Persian coup d'état, and su ...

as the new prime minister. Reza Khan's first role in the new government was commander-in-chief of the army and the minister of war.

Two years after the coup, Seyyed Zia appointed Reza Pahlavi as Iran's prime minister, backed by the compliant national assembly of Iran. In 1925, Reza Pahlavi was appointed as the legal monarch of Iran by the decision of Iran's constituent assembly. The assembly deposed Ahmad Shah Qajar

Ahmad Shah Qajar ( fa, احمد شاه قاجار; 21 January 1898 – 21 February 1930) was Shah of Persia (Iran) from 16 July 1909 to 15 December 1925, and the last ruling member of the Qajar dynasty.

Ahmad Shah was born in Tabriz on 21 Janu ...

, the last Shah

Shah (; fa, شاه, , ) is a royal title that was historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies.Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) It was also used by a variety of ...

of the Qajar dynasty

The Qajar dynasty (; fa, دودمان قاجار ', az, Qacarlar ) was an IranianAbbas Amanat, ''The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896'', I. B. Tauris, pp 2–3 royal dynasty of Turkic peoples ...

, and amended Iran's 1906 constitution to allow selection of Reza Pahlavi as the Shah of Iran. He founded the Pahlavi dynasty that lasted until overthrown in 1979 during the Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

.

In the spring of 1950, he was posthumously named as Reza Shah the Great () by Iran's National Consultative Assembly

The National Consultative Assembly ( fa, مجلس شورای ملی, Mad̲j̲les-e s̲h̲ūrā-ye mellī) or simply Majles, was the national legislative body of Iran from 1906 to 1979.

It was elected by universal suffrage, excluding the armed for ...

.''تاریخ بیست ساله ایران''، حسین مکی، نشر ناشر، ۱۳۶۳ تهراننجفقلی پسیان و خسرو معتضد، ''از سوادکوه تا ژوهانسبورگ: زندگی رضاشاه پهلوی''، نشر ثالث، ۷۸۶ صفحه، چاپ سوم، ۱۳۸۲، ویژه:منابع کتاب/

His legacy remains controversial to this day. His defenders assert that he was an essential reunification modernization force for Iran (whose international prominence had sharply declined during Qajar rule), while his detractors assert that his reign was often despotic, with his failure to modernize Iran's large peasant population eventually sowing the seeds for the Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

nearly four decades later, which ended 2,500 years of Persian monarchy. Moreover, his insistence on ethnic

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

and cultural unitarism, along with forced detribalization and sedentarization

In cultural anthropology, sedentism (sometimes called sedentariness; compare sedentarism) is the practice of living in one place for a long time. , the large majority of people belong to sedentary cultures. In evolutionary anthropology and ar ...

, resulted in the suppression of several ethnic and social groups. Although he himself was of Iranian Mazanderani descent, his government carried out an extensive policy of Persianization

Persianization () or Persification (; fa, پارسیسازی), is a sociological process of cultural change in which a non-Persian society becomes "Persianate", meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Persian ...

trying to create a single, united and largely homogeneous nation, similar to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

's policy of Turkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

after the fall of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

.

Early life

Reza Shah Pahlavi was born in the town of

Reza Shah Pahlavi was born in the town of Alasht

Alasht ( fa, آلاشت, ', meaning ''Eagle Sanctuary'', also Romanized as Ālāsht) is a city in the Central District of Savadkuh County, Mazandaran Province, Iran. At the 2016 census, its population was 1,193.

Alasht is isolated by surroundin ...

in Savadkuh County

Savadkuh County ( fa, شهرستان سوادكوه, ''Ŝahrestāne Sawādkuh''; also Savadkooh and Savadkouh) is located in Mazandaran province, Mazandaran province, Iran. The capital of the county is Pol Sefid, Mazandaran, Pol Sefid. At the 20 ...

, Mazandaran Province, in 1878, to son of Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

Abbas-Ali Khan and wife Noush-Afarin. His mother was a Georgian

Georgian may refer to:

Common meanings

* Anything related to, or originating from Georgia (country)

** Georgians, an indigenous Caucasian ethnic group

** Georgian language, a Kartvelian language spoken by Georgians

**Georgian scripts, three scrip ...

Muslim immigrant from Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

(then part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

), whose family had emigrated to Qajar Iran

Qajar Iran (), also referred to as Qajar Persia, the Qajar Empire, '. Sublime State of Persia, officially the Sublime State of Iran ( fa, دولت علیّه ایران ') and also known then as the Guarded Domains of Iran ( fa, ممالک م ...

when it was forced to cede all of its territories in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

following the Russo-Persian Wars

The Russo-Persian Wars or Russo-Iranian Wars were a series of conflicts between 1651 and 1828, concerning Iran, Persia (Iran) and the Russian Empire. Russia and Persia fought these wars over disputed governance of territories and countries in th ...

several decades prior to Reza Shah's birth. His father was a Mazanderani, commissioned in the 7th Savadkuh

Savadkuh County ( fa, شهرستان سوادكوه, ''Ŝahrestāne Sawādkuh''; also Savadkooh and Savadkouh) is located in Mazandaran province, Iran. The capital of the county is Pol Sefid. At the 2006 census, the county's population (includi ...

Regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

, and served in the Siege of Herat in 1856. Abbas-Ali died suddenly on 26 November 1878, when Reza was barely 8 months old. Upon his father's death, Reza and his mother moved to her brother's house in Tehran. She remarried in 1879 and left Reza to the care of his uncle. In 1882, his uncle in turn sent Reza to a family friend, Amir Tuman Kazim Khan, an officer in the Persian Cossack Brigade, in whose home he had a room of his own and a chance to study with Kazim Khan's children with the tutors who came to the house. When Reza was sixteen years old, he joined the Persian Cossack Brigade

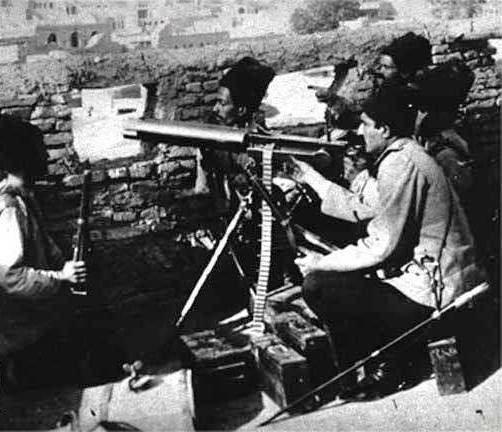

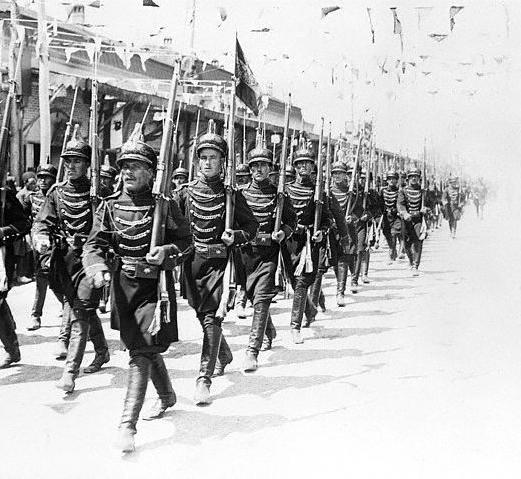

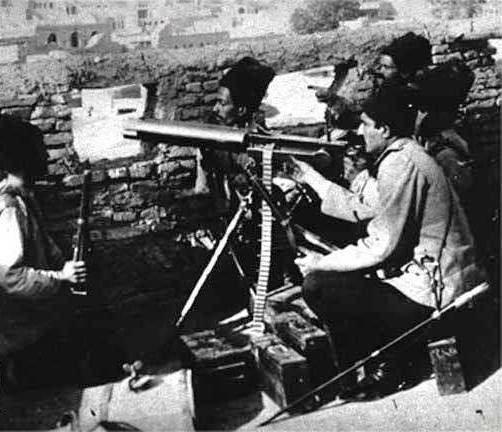

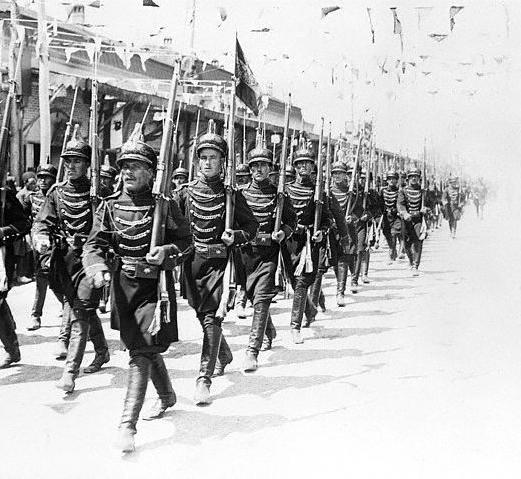

, image = Persian Cossack Brigade.jpg

, caption = Persian Cossack Brigade in Tabriz in 1909

, dates = 1879–1921

, disbanded = 6 December 1921

, count ...

. In 1903, when he was 25 years old, he is reported to have been guard and servant to the Dutch consul general Fridolin Marinus Knobel.

He also served in the Imperial Army. His initial career started as a private under Qajar Prince Abdol-Hossein Farman Farma

Prince Abdol-Hossein Farman Farma ( fa, عبدالحسین فرمانفرما 1857 – November, 1939) was one of the most prominent Qajar princes, and one of the most influential politicians of his time in Persia. He was born in Tehran to P ...

's command. Farman Farma noted that Reza had potential and sent him to military school where he gained the rank of gunnery sergeant. In 1911, he gave a good account of himself in later campaigns and was promoted to First Lieutenant. His proficiency in handling machine guns elevated him to the rank equivalent to captain in 1912. By 1915, he was promoted to the rank of Colonel. His record of military service eventually led him to a commission as a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in the Persian Cossack Brigade

, image = Persian Cossack Brigade.jpg

, caption = Persian Cossack Brigade in Tabriz in 1909

, dates = 1879–1921

, disbanded = 6 December 1921

, count ...

. He was the last commanding officer of the Brigade, and the only Iranian commander in its history, succeeding to this position the Russian colonel Vsevolod Starosselsky Vsevolod Starosselsky (Vsevolod Dmitryevich Staroselsky, russian: Все́волод Дми́триевич Старосе́льский; 7 March 1875 – 29 June 1935) was a Russian military officer of Russian and Georgian noble background, known ...

, whom Reza Shah had helped, in 1918, take over the brigade.

In November 1919, he chose the last name Pahlavi for himself, which later became the name of the dynasty he founded.

Rise to power

1921 coup

In the aftermath of the

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

, Persia had become a battleground. In 1917, Britain used Iran as the springboard for the launching of an expedition into Russia as part of their intervention in the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

on the side of the White movement. The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

responded by annexing portions of northern Persia, creating the Persian Socialist Soviet Republic

The Persian Socialist Soviet Republic ( fa, ), also known as the Soviet Republic of Iran or Socialist Soviet Republic of Gilan, was a short-lived unrecognized state, a Soviet republic in the Iranian province of Gilan that lasted from June 1920 ...

. The Soviets extracted ever more humiliating concessions from the Qajar government, whose ministers Ahmad Shah was often unable to control. By 1920, the government had lost virtually all power outside its capital: British and Soviet forces exercised control over most of the Iranian mainland.

In late 1920, the Soviets in Rasht

Rasht ( fa, رشت, Rašt ; glk, Rəšt, script=Latn; also romanized as Resht and Rast, and often spelt ''Recht'' in French and older German manuscripts) is the capital city of Gilan Province, Iran. Also known as the "City of Rain" (, ''Ŝahre B ...

prepared to march on Tehran with "a guerrilla force of 1,500 Jangalis, Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ir ...

, Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, ''hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

, and Azerbaijanis

Azerbaijanis (; az, Azərbaycanlılar, ), Azeris ( az, Azərilər, ), or Azerbaijani Turks ( az, Azərbaycan Türkləri, ) are a Turkic people living mainly in northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. They are the second-most numer ...

", reinforced by the Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

. This, along with various other unrest in the country, created "an acute political crisis in the capital."

On 14 January 1921, the commander of the British Forces in Iran, General Edmund "Tiny" Ironside, promoted Reza Khan, who had been leading the Tabriz battalion, to lead the entire brigade. About a month later, under British direction, Reza Khan led his 3,000-4,000 strong detachment of the Cossack Brigade, based in Niyarak, Qazvin, and Hamadan, to Tehran and seized the capital. He forced the dissolution of the previous government and demanded that Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabaee be appointed Prime Minister. para. 2, 3 Reza Khan's first role in the new government was as commander of the Iranian Army, which he combined with the post of

On 14 January 1921, the commander of the British Forces in Iran, General Edmund "Tiny" Ironside, promoted Reza Khan, who had been leading the Tabriz battalion, to lead the entire brigade. About a month later, under British direction, Reza Khan led his 3,000-4,000 strong detachment of the Cossack Brigade, based in Niyarak, Qazvin, and Hamadan, to Tehran and seized the capital. He forced the dissolution of the previous government and demanded that Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabaee be appointed Prime Minister. para. 2, 3 Reza Khan's first role in the new government was as commander of the Iranian Army, which he combined with the post of Minister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

. He took the title Sardar Sepah ( fa, سردار سپاه), or Commander-in-Chief of the Army, by which he was known until he became Shah. While Reza Khan and his Cossack brigade secured Tehran, the Persian envoy in Moscow negotiated a treaty with the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s for the removal of Soviet troops from Persia. Article IV of the Russo-Persian Treaty of Friendship allowed the Soviets to invade and occupy Persia, should they believe foreign troops were using it as a staging area for an invasion of Soviet territory. As Soviets interpreted the treaty, they could invade if events in Persia should prove threatening to Soviet national security. This treaty would cause enormous tension between the two nations until the Anglo-Soviet Invasion of Iran.

The coup d'état of 1921 was partially assisted by the British government, which wished to halt the Bolsheviks' penetration of Iran, particularly because of the threat it posed to the British possessions in India. It is thought that the British provided "ammunition, supplies and pay" for Reza's troops. On 8 June 1932, a British Embassy report states that the British were interested in helping Reza Shah create a centralizing power. General Ironside

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal William Edmund Ironside, 1st Baron Ironside, (6 May 1880 – 22 September 1959) was a senior officer of the British Army who served as Chief of the General Staff (United Kingdom), Chief of the Impe ...

gave a situation report to the British War Office saying that a capable Persian officer was in command of the Cossacks and this "would solve many difficulties and enable us to depart in peace and honour".

Reza Khan spent the rest of 1921 securing Iran's interior, responding to a number of revolts that erupted against the new government. Among the greatest threats to the new administration were the Persian Soviet Socialist Republic, which had been established in Gilan, and the Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ir ...

of Khorasan

Khorasan may refer to:

* Greater Khorasan, a historical region which lies mostly in modern-day northern/northwestern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

* Khorasan Province, a pre-2004 province of Ira ...

.

Overthrow of the Qajar dynasty

From the beginning of the appointment of Reza Khan as the minister of war, there was ever increasing tension with

From the beginning of the appointment of Reza Khan as the minister of war, there was ever increasing tension with Zia ol Din Tabatabaee

Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabataba'i (June 1889 – 29 August 1969; fa, سید ضیاءالدین طباطبایی) was an Iranian journalist and politician who, with the help of Reza Shah, Reza Khan Savadkuhi, led the 1921 Persian coup d'état, and su ...

, who was prime minister at the time. Zia ol Din Tabatabaee wrongly calculated that when Reza Khan was appointed as the minister of war, he would relinquish his post as the head of the Persian Cossack Brigade

, image = Persian Cossack Brigade.jpg

, caption = Persian Cossack Brigade in Tabriz in 1909

, dates = 1879–1921

, disbanded = 6 December 1921

, count ...

, and that Reza Khan would wear civilian clothing instead of the military attire. This erroneous calculation by Zia ol Din Tabatabaee backfired and instead it was apparent to people who observed Reza Khan, including members of parliament, that he (and not Zia ol Din Tabatabaee) was the one who wielded power.

By 1923, Reza Khan had largely succeeded in securing Iran's interior from any remaining domestic and foreign threats. Upon his return to the capital he was appointed Prime Minister, which prompted Ahmad Shah to leave Iran for Europe, where he would remain (at first voluntarily, and later in exile) until his death. It induced the Parliament to grant Reza Khan dictatorial powers, who in turn assumed the symbolic and honorific styles of ''Janab

Janab, Janaab or Janob (Persian spelling) (; ) is an Islamic honorary title, which means "Sir" in English. The title has been carried by many Islamic poet and writers. The compound style Janab-e-Ashraf (جانبِ الشرف ''janāb-i ashraf'' - ...

-i-Ashraf'' (His Serene Highness) and ''Hazrat

''Hazrat, , ,'' or ' ( ar, حَضْرَة, ḥaḍra, pl. ''ḥaḍrāt''; Persian: pronounced or ) is a common Bangladeshi, Indian, Pakistani, Iranian, Afghan, and honorific Arabic and Turkish title used to honour a person. It literally deno ...

-i-Ashraf'' on 28 October 1923. He quickly established a political cabinet in Tehran to help organize his plans for modernization and reform.

By October 1925, he succeeded in pressuring the Majlis

( ar, المجلس, pl. ') is an Arabic term meaning "sitting room", used to describe various types of special gatherings among common interest groups of administrative, social or religious nature in countries with linguistic or cultural conne ...

to depose and formally exile Ahmad Shah, and instate him as the next Shah of Iran. Initially, he had planned to declare the country a republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

, as his contemporary Atatürk had done in Turkey, but abandoned the idea in the face of British and clerical opposition.

The Majlis, convening as a constituent assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

, declared him the Shah

Shah (; fa, شاه, , ) is a royal title that was historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies.Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) It was also used by a variety of ...

(King) of Iran on 12 December 1925, pursuant to the Persian Constitution of 1906

The Persian Constitution of 1906 ( fa, قانون اساسی مشروطه, Qanun-e Asasi-ye Mishirutâh), was the first constitution of the Sublime State of Persia (Qajar Iran), resulting from the Persian Constitutional Revolution and it was w ...

. Three days later, on 15 December, he took his imperial oath and thus became the first shah of the Pahlavi dynasty

The Pahlavi dynasty ( fa, دودمان پهلوی) was the last Iranian royal dynasty, ruling for almost 54 years between 1925 and 1979. The dynasty was founded by Reza Shah Pahlavi, a non-aristocratic Mazanderani soldier in modern times, who ...

. Reza Shah's coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

took place much later, on 25 April 1926. It was at that time that his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 October ...

, was proclaimed crown prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the wif ...

.

Rule as the Shah

While the Shah left behind no major thesis, or speeches giving an overarching policy, his reforms indicated a striving for an Iran which—according to scholar

While the Shah left behind no major thesis, or speeches giving an overarching policy, his reforms indicated a striving for an Iran which—according to scholar Ervand Abrahamian

Ervand Abrahamian; hy, Երուանդ Աբրահամեան (born 1940) is an Iranian-American historian of the Middle East. He is Distinguished Professor of History at Baruch College and the Graduate Center, CUNY, Graduate Center of the City Un ...

—would be "free of clerical influence, nomadic uprisings, and ethnic differences", on the one hand, and on the other hand would contain "European-style educational institutions, Westernized women active outside the home, and modern economic structures with state factories, communication networks, investment banks, and department stores."

Reza is said to have avoided political participation and consultation with politicians or political personalities, instead embracing the slogan "every country has its own ruling system and ours is a one man system." He is also said to have preferred punishment to reward in dealing with subordinates or citizens.

Reza Shah's reign has been said to have consisted of "two distinct periods". From 1925 to 1933, figures such as Abdolhossein Teymourtash

Abdolhossein Teymourtash ( fa, عبدالحسین تیمورتاش; 25 September 1883 – 3 October 1933) was an influential Iranian statesman who served as the first minister of court of the Pahlavi dynasty from 1925 to 1932, and is credited w ...

, Nosrat ol Dowleh Firouz, and Ali-Akbar Davar

Ali-Akbar Dāvar ( fa, علیاکبر داور also known as Mirza Ali-Akbar Khan-e Dāvar, 1885 – 9 February 1937) was an Iranian politician and judge and the founder of the modern judicial system of Iran.

Biography

Born in 1885

and many other western-educated Iranians emerged to implement modernist plans, such as the construction of railways, a modern judiciary and educational system, and the imposition of changes in traditional attire, and traditional and religious customs and mores. In the second half of his reign (1933–41), which the Shah described as "one-man rule", strong personalities like Davar and Teymourtash were removed, and secularist and Western policies and plans initiated earlier were implemented.

Modernization

During Reza Shah's sixteen years of rule, major developments, such as large road construction projects and the

During Reza Shah's sixteen years of rule, major developments, such as large road construction projects and the Trans-Iranian Railway

The Trans-Iranian Railway ( fa, راهآهن سراسری ایران) was a major railway building project started in Pahlavi Iran in 1927 and completed in 1938, under the direction of the then-Iranian monarch Reza Shah. It was entirely built ...

were built, modern education was introduced and the University of Tehran

The University of Tehran (Tehran University or UT, fa, دانشگاه تهران) is the most prominent university located in Tehran, Iran. Based on its historical, socio-cultural, and political pedigree, as well as its research and teaching pro ...

, the first Iranian university, was established. The government sponsored European education for many Iranian students The number of modern industrial plants increased 17-fold under Reza Shah (excluding oil installations), and the number of miles of highway increased from 2,000 to 14,000.

Along with the modernization of the nation, Reza Shah was the ruler during the time of the Women's Awakening (1936–1941). This movement sought the elimination of the

Along with the modernization of the nation, Reza Shah was the ruler during the time of the Women's Awakening (1936–1941). This movement sought the elimination of the chador

A chādor ( Persian, ur, چادر, lit=tent), also variously spelled in English as chadah, chad(d)ar, chader, chud(d)ah, chadur, and naturalized as , is an outer garment or open cloak worn by many women in the Persian-influenced countries of I ...

from Iranian working society. Supporters held that the veil impeded physical exercise and the ability of women to enter society and contribute to the progress of the nation. This move met opposition from the Mullahs from the religious establishment. The unveiling issue and the Women's Awakening are linked to the Marriage Law of 1931 and the Second Congress of Eastern Women in Tehran in 1932.

Reza Shah was the first Iranian Monarch in 1400 years who paid respect to the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

by praying in the synagogue when visiting the Jewish community of Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

; an act that boosted the self-esteem of the Iranian Jews

Persian Jews or Iranian Jews ( fa, یهودیان ایرانی, ''yahudiān-e-Irāni''; he, יהודים פרסים ''Yəhūdīm Parsīm'') are the descendants of Jews who were historically associated with the Persian Empire, whose successor s ...

and made Reza Shah their second most respected Iranian leader after Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

. Reza Shah's reforms opened new occupations to Jews and allowed them to leave the ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

. This point of view, however, may be refuted by the claims that the anti-Jewish incidents of September 1922 in parts of Tehran was a plot by Reza Khan.

He forbade photographing aspects of Iran he considered backwards such as camels, and he banned clerical dress and chadors in favor of Western dress.

Parliament and ministers

Parliamentary elections during the Shah's reign were not democratic. The general practice was to "draw up, with the help of the police chief, a list of parliamentary candidates for the interior minister. The interior minister then passed the same names onto the provincial governor-general. ... hohanded down the list to the supervisory electoral councils that were packed by the Interior Ministry to oversee the ballots. Parliament ceased to be a meaningful institution, and instead became a decorative garb covering the nakedness of military rule."

Reza Shah discredited and eliminated a number of his ministers. His minister of Imperial Court,

Parliamentary elections during the Shah's reign were not democratic. The general practice was to "draw up, with the help of the police chief, a list of parliamentary candidates for the interior minister. The interior minister then passed the same names onto the provincial governor-general. ... hohanded down the list to the supervisory electoral councils that were packed by the Interior Ministry to oversee the ballots. Parliament ceased to be a meaningful institution, and instead became a decorative garb covering the nakedness of military rule."

Reza Shah discredited and eliminated a number of his ministers. His minister of Imperial Court, Abdolhossein Teymourtash

Abdolhossein Teymourtash ( fa, عبدالحسین تیمورتاش; 25 September 1883 – 3 October 1933) was an influential Iranian statesman who served as the first minister of court of the Pahlavi dynasty from 1925 to 1932, and is credited w ...

, was accused and convicted of corruption, bribery, misuse of foreign currency regulations, and plans to overthrow the Shah. He was removed as the minister of court in 1932 and died under suspicious circumstances while in prison in September 1933. The minister of finance, Prince Firouz Nosrat-ed-Dowleh III

Prince Firouz Nosrat-ed-Dowleh III, GCMG (1889–1937) was the eldest son of Prince Abdol-Hossein Farmanfarma and Princess Ezzat-ed-Dowleh Qajar. He was born in 1889 and died in April 1937. He was the grandson of his namesake, Nosrat Dowleh Firou ...

, who played an important role in the first three years of his reign, was convicted on similar charges in May 1930, and also died in prison, in January 1938. Ali-Akbar Davar

Ali-Akbar Dāvar ( fa, علیاکبر داور also known as Mirza Ali-Akbar Khan-e Dāvar, 1885 – 9 February 1937) was an Iranian politician and judge and the founder of the modern judicial system of Iran.

Biography

Born in 1885

, his minister of justice, was suspected of similar charges and committed suicide in February 1937. The elimination of these ministers "deprived" Iran "of her most dynamic figures ... and the burden of government fell heavily on Reza Shah" according to historian Cyrus Ghani.

Replacement of ''Persia'' with ''Iran''

In the

In the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

, Persia (or its cognates) was historically the common name for Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. In 1935, Reza Shah asked foreign delegates and League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

to use the term Iran ("Land of the Aryans

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

"), the endonym of the country, used by its native people, in formal correspondence. Since then, in the Western World, the use of the word "Iran" has become more common. This also changed the usage of the names for the Iranian nationality, and the common adjective for citizens of Iran changed from Persian to Iranian. In 1959, the government of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 Octobe ...

, Reza Shah Pahlavi's son and successor, announced that both "Persia" and "Iran" could officially be used interchangeably, nonetheless use of "Iran" continued to subplant "Persia", especially in the West. Though the predominant and official language of the country was the Persian language

Persian (), also known by its endonym Farsi (, ', ), is a Western Iranian language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian subdivision of the Indo-European languages. Persian is a pluricentric language predominantly spoken and ...

, many did not consider themselves ethnic Persians, whereas "Iranians" made for a much more neutral and unifying reference too all the ethnic groups of Iran, further, "Persia" (locally known as Pars) was geographically confusing at times as it was also the name of one of Iran's significant cultural provinces. Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi

, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) Although (internally) the country had been referred to as Iran throughout much of its history since the

Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

, many countries including the English-speaking world

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the '' Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest languag ...

knew the country as Persia, largely a legacy of the Ancient Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

name for the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

.

Support and opposition

Support for the Shah came principally from three sources. The central "pillar" was the military, where the shah had begun his career. The annual defense budget of Iran "increased more than fivefold from 1926 to 1941." Officers were paid more than other salaried employees. The new modern and expanded state bureaucracy of Iran was another source of support. Its ten civilian ministries employed 90,000 full-time government workers. Patronage controlled by the Shah's royal court served as the third "pillar". This was financed by the Shah's considerable personal wealth which had been built up by forced sales and confiscations of estates, making him "the richest man in Iran". On his abdication Reza Shah "left to his heir a bank account of some three million pounds sterling and estates totaling over 3 million acres." Opposition to the Shah came not so much from the landed upper class as from "the tribes, the clergy, and the young generation of the new intelligentsia. The tribes bore the brunt of the new order."Clash with the clergy

As his reign became more secure, Reza Shah clashed with Iran's clergy and devout Muslims on many issues. In March 1928, he violated the sanctuary of Qom'sFatima Masumeh Shrine

The Shrine of Fatima Masumeh ( fa, حرم فاطمه معصومه translit. ''haram-e fateme-ye masumeh'') is located in Qom, which is considered by Shia Muslims to be the second most sacred city in Iran after Mashhad.

Fatima Masumeh was the ...

to beat a cleric who had angrily admonished Reza Shah's wife for temporarily exposing her face a day earlier while on pilgrimage to Qom. In December of that year he instituted a law requiring everyone (except Shia jurisconsults who had passed a special qualifying examination) to wear Western clothes. This angered devout Muslims because it included a hat with a brim which prevented the devout from touching their foreheads on the ground during salat

(, plural , romanized: or Old Arabic ͡sˤaˈloːh, ( or Old Arabic ͡sˤaˈloːtʰin construct state) ), also known as ( fa, نماز) and also spelled , are prayers performed by Muslims. Facing the , the direction of the Kaaba wit ...

as required by Islamic law.Abrahamian, ''History of Modern Iran'', (2008), pp. 93–94 The Shah also encouraged women to discard hijab

In modern usage, hijab ( ar, حجاب, translit=ḥijāb, ) generally refers to headcoverings worn by Muslim women. Many Muslims believe it is obligatory for every female Muslim who has reached the age of puberty to wear a head covering. While ...

. He announced that female teachers could no longer come to school with head coverings. One of his daughters reviewed a girls' athletic event with an uncovered head.

The devout were also angered by policies that allowed mixing of the sexes. Women were allowed to study in the colleges of law and medicine, and in 1934 a law set heavy fines for cinemas, restaurant, and hotels that did not open their doors to both sexes. Doctors were permitted to dissect human bodies. He restricted public mourning observances to one day and required mosques to use chairs instead of the traditional sitting on the floors of mosques.

By the mid-1930s, Reza Shah's rule had caused intense dissatisfaction of the

The devout were also angered by policies that allowed mixing of the sexes. Women were allowed to study in the colleges of law and medicine, and in 1934 a law set heavy fines for cinemas, restaurant, and hotels that did not open their doors to both sexes. Doctors were permitted to dissect human bodies. He restricted public mourning observances to one day and required mosques to use chairs instead of the traditional sitting on the floors of mosques.

By the mid-1930s, Reza Shah's rule had caused intense dissatisfaction of the Shia clergy

In Shi'a Islam the guidance of clergy and keeping such a structure holds a great importance. The clergy structure depends on the branch of Shi'ism is being referred to.

Twelver

Usooli and Akhbari Shia Twelver Muslims believe that the study o ...

throughout Iran. In 1935, a rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

erupted in the Imam Reza Shrine in Mashhad

Mashhad ( fa, مشهد, Mašhad ), also spelled Mashad, is the List of Iranian cities by population, second-most-populous city in Iran, located in the relatively remote north-east of the country about from Tehran. It serves as the capital of R ...

. Responding to a cleric who denounced the Shah's "heretical" innovations, corruption and heavy consumer taxes, many bazaaris and villagers took refuge in the shrine, chanting slogans such as "The Shah is a new Yezid." For four full days local police and army refused to violate the shrine. The standoff was ended when troops from Iranian Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan or Azarbaijan ( fa, آذربایجان, ''Āzarbāijān'' ; az-Arab, آذربایجان, ''Āzerbāyjān'' ), also known as Iranian Azerbaijan, is a historical region in northwestern Iran that borders Iraq, Turkey, the Nakhchivan ...

arrived and broke into the shrine, killing dozens and injuring hundreds, and marking a final rupture between the clergy and the Shah. Some of the Mashed clergy even left their jobs, such as the Keeper of the Keys of the shrine Hassan Mazloumi, later named Barjesteh, who stated he did not want to listen to the orders of a dog.

The Shah intensified his controversial changes following the incident with the ''Kashf-e hijab

On 8 January 1936, Reza Shah of Iran (Persia) issued a decree known as ''Kashf-e hijab'' (also Romanized as "Kashf-e hijāb" and "Kashf-e hejāb", fa, کشف حجاب, lit=Unveiling) banning all Islamic veils (including hijab and chador), a ...

'' decree, banning the chador

A chādor ( Persian, ur, چادر, lit=tent), also variously spelled in English as chadah, chad(d)ar, chader, chud(d)ah, chadur, and naturalized as , is an outer garment or open cloak worn by many women in the Persian-influenced countries of I ...

and ordering all citizens – rich and poor – to bring their wives to public functions without head coverings.

Foreign affairs and influence

Reza Shah initiated change in foreign affairs as well. He worked to balance British influence with other foreigners and generally to diminish foreign influence in Iran.

One of the first acts of the new government after the 1921 entrance into Tehran was to tear up the treaty with the

Reza Shah initiated change in foreign affairs as well. He worked to balance British influence with other foreigners and generally to diminish foreign influence in Iran.

One of the first acts of the new government after the 1921 entrance into Tehran was to tear up the treaty with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. The Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

condemned the aggressive foreign policy of Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

, promised never to interfere in Persia's internal affairs, but reserved the right to occupy it temporarily in the event another power used Persia for an attack on Soviet Russia.

In 1934 he made an official state visit to Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

and met Turkish President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

. During their meeting Reza Shah spoke in Azerbaijani, and Atatürk in Turkish.

In 1931, he refused to allow Imperial Airways

Imperial Airways was the early British commercial long-range airline, operating from 1924 to 1939 and principally serving the British Empire routes to South Africa, India, Australia and the Far East, including Malaya and Hong Kong. Passenger ...

to fly in Persian airspace, instead giving the concession to German-owned Lufthansa Airlines. The next year, 1932, he surprised the British by unilaterally canceling the oil concession awarded to William Knox D'Arcy

William Knox D'Arcy (11 October 18491 May 1917) was a British businessman who was one of the principal founders of the oil and petrochemical industry in Persia (Iran). The D’Arcy Concession was signed in 1901 and allowed D'Arcy to explore, o ...

(and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) was a British company founded in 1909 following the discovery of a large oil field in Masjed Soleiman, Persia (Iran). The British government purchased 51% of the company in 1914, gaining a controlling number ...

), which was slated to expire in 1961. The concession granted Persia 16% of the net profits from APOC oil operations. The Shah wanted 21%. The British took the dispute before the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. However, before a decision was made by the League, the company and Iran compromised and a new concession was signed on 26 April 1933.

He previously hired American consultants to develop and implement Western-style financial and administrative systems. Among them was U.S. economist Arthur Millspaugh

Arthur Chester Millspaugh, PhD, (1883–1955) was a former adviser at the U.S. State Department’s Office of the Foreign Trade, who was hired to re-organize the Finance Ministry of Iran from 1922–1927 and 1942-1945.

With his help, Iran became ...

, who acted as the nation's finance minister. Reza Shah also purchased ships from Italy and hired Italians to teach his troops the intricacies of naval warfare. He also imported hundreds of German technicians and advisors for various projects. Mindful of Persia's long period of subservience to British and Russian authority, Reza Shah was careful to avoid giving any one foreign nation too much control. He also insisted that foreign advisors be employed by the Persian government, so that they would not be answerable to foreign powers. This was based upon his experience with Anglo-Persian, which was owned and operated by thBritish government

Indo-European Telegraph Company

Siemens Communications was the communications and information business arm of German industrial conglomerate Siemens AG, until 2006. It was the largest division of Siemens, and had two business units – Mobile Networks and Fixed Networks; and En ...

to the Iranian government, in addition to the collection of customs by Belgian officials. He eventually fired Millspaugh, and prohibited foreigners from administering schools, owning land or traveling in the provinces without police permission.

Not all observers agree that the Shah minimized foreign influence. One complaint about his development program was that the north–south railway line he had built was uneconomical, only serving the British, who had a military presence in the south of Iran and desired the ability to transfer their troops north to Russia, as part of their strategic defence plan. In contrast, the Shah's regime did not develop what critics believe was an economically justifiable east–west railway system.

On 21 March 1935, he issued a decree asking foreign delegates to use the term ''Iran'' in formal correspondence, as ''Persia'' is a term used for a country identified as ''Iran'' in the Persian language

Persian (), also known by its endonym Farsi (, ', ), is a Western Iranian language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian subdivision of the Indo-European languages. Persian is a pluricentric language predominantly spoken and ...

. It was, however, attributed more to the Iranian people than others, as ''Iran'' means "Land of the Aryans". This wisdom of this decision continues to be debated.

Tired of the opportunistic policies of both Britain and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, the Shah circumscribed contacts with foreign embassies. Relations with the Soviet Union had already deteriorated because of that country's commercial policies, which in the 1920s and 1930s adversely affected Iran. In 1932, the Shah offended Britain by canceling the agreement under which the Anglo-Persian Oil Company produced and exported Iran's oil. Although a new and improved agreement was eventually signed, it did not satisfy Iran's demands and left bad feeling on both sides.

To counterbalance British and Soviet influence, Reza Shah encouraged German commercial enterprise in Iran. On the eve of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Germany was Iran's largest trading partner. The Germans agreed to sell the Shah the steel factory he coveted and considered a ''sine qua non'' of progress and modernity. Reza Shah's foreign policy, which had consisted largely on playing the Soviet Union off against the United Kingdom, failed when the German invasion of the USSR in 1941, resulted in those two powers becoming sudden allies in the fight against the Axis powers. Seeking to guarantee the continued supply for to United Kingdom and in order to secure a route of supply to provide Soviet forces with war material, the two allies jointly launched a surprise invasion in August 1941. Caught off guard, out gunned and diplomatically isolated, Reza Shah decided not to the resist the Anglo-Soviet invasion, ordering his forces to surrender before agreeing to abdicate the throne in favor of his son. Reza Shah then went into exile while Iran would remain under Allied occupation until 1946.

Later years of reign

The Shah's reign is sometimes divided into periods. All the worthwhile efforts of Reza Shah's reign were either completed or conceived in the 1925–1938 period, a period during which he required the assistance of reformists to gain the requisite legitimacy to consolidate this modern reign. In particular, Abdolhossein

The Shah's reign is sometimes divided into periods. All the worthwhile efforts of Reza Shah's reign were either completed or conceived in the 1925–1938 period, a period during which he required the assistance of reformists to gain the requisite legitimacy to consolidate this modern reign. In particular, Abdolhossein Teymourtash

Abdolhossein Teymourtash ( fa, عبدالحسین تیمورتاش; 25 September 1883 – 3 October 1933) was an influential Iranian statesman who served as the first minister of court of the Pahlavi dynasty from 1925 to 1932, and is credited ...

assisted by Farman Farma, Ali-Akbar Davar

Ali-Akbar Dāvar ( fa, علیاکبر داور also known as Mirza Ali-Akbar Khan-e Dāvar, 1885 – 9 February 1937) was an Iranian politician and judge and the founder of the modern judicial system of Iran.

Biography

Born in 1885

and a large number of modern educated Iranians, proved adept at masterminding the implementation of many reforms demanded since the failed constitutional revolution of 1905–1911. The preservation and promotion of the country's historic heritage, the provision of public education, construction of a national railway, abolition of capitulation agreements, and the establishment of a national bank had all been advocated by intellectuals since the tumult of the constitutional revolution.

The later years of his reign were dedicated to institutionalizing the educational system of Iran and also to the industrialization of the country. He knew that the system of the constitutional monarchy in Iran after him had to stand on a solid basis of the collective participation of all Iranians, and that it was indispensable to create educational centers all over Iran.

Reza Shah attempted to forge a regional alliance with Iran's Middle Eastern neighbors, particularly

Reza Shah attempted to forge a regional alliance with Iran's Middle Eastern neighbors, particularly Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. The death of Ataturk in 1938, followed by the start of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

shortly thereafter, prevented these projects from being realized.

The parliament assented to his decrees, the free press was suppressed, and the swift incarceration of political leaders like Mossadegh, the murder of others such as Teymourtash, Sardar Asad, Firouz, Modarres, Arbab Keikhosro and the suicide of Davar, ensured that any progress towards democratization was stillborn and organized opposition to the Shah, impossible. Reza Shah treated the urban middle class, the managers, and technocrats

Technocracy is a form of government in which the decision-maker or makers are selected based on their expertise in a given area of responsibility, particularly with regard to scientific or technical knowledge. This system explicitly contrasts wi ...

with an iron fist; as a result his state-owned industries remained underproductive and inefficient. The bureaucracy fell apart, since officials preferred sycophancy, when anyone could be whisked away to prison for even the whiff of disobeying his whims.Rubin, ''Paved with Good Intentions''. He confiscated land from the Qajars and from his rivals and into his own estates. The corruption continued under his rule and even became institutionalized. Progress toward modernization was spotty and isolated as it could only take place with Shah's approval.Nikki R. Keddie and Yann Richard

Yann is a French male given name, specifically, the Breton form of "Jean" (French for "John").

Notable persons with the name Yann include:

__NOTOC__

In arts and entertainment

*Yann Martel (born 1963), Canadian author

*Yann Moix (born 1968), Fr ...

, ''Roots of Revolution'' (Yale University, 1981: ). Eventually the Shah became totally dependent on the military and secret police to retain power; in return, these state organs regularly received funding up to 50 percent of available public revenue to ensure their loyalty.

Although the landed aristocracy lost most of their influence during Reza Shah's reign, his regime aroused opposition not from them or the gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest ...

but from Iran's: "tribes, the clergy, and the young generation of the new intelligentsia. The tribes bore the brunt of the new order."

World War II and forced abdication

In August 1941 the Allied powers, the

In August 1941 the Allied powers, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

invaded and occupied neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

Iran by a massive air, land, and naval assault without a declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state (polity), state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a nationa ...

. By 28–29 August, the Iranian military situation was in complete chaos. The Allies had complete control over the skies of Iran, and large sections of the country were in their hands. Major Iranian cities (such as Tehran) were suffering repeated air raids. In Tehran itself, the casualties had been light, but the Soviet Air Force dropped leaflets over city, warning the population of an upcoming massive bombing raid and urging them to surrender before they suffered imminent destruction. Tehran's water and food supply had faced shortages, and soldiers fled in fear of the Soviets killing them upon capture. Faced with total collapse, the royal family (except the Shah and the Crown Prince) fled to Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

.

The collapse of the army that Reza Shah had spent so much time and effort creating was humiliating. Many Iranian commanders behaved incompetently, others secretly sympathized with the British and sabotaged Iranian resistance. The army generals met in secret to discuss surrender options. When the Shah learned of the generals' actions, he beat armed forces chief General Ahmad Nakhjavan with a cane and physically stripped him of his rank. Nakhjavan was nearly shot by the Shah on the spot, but at the insistence of the Crown Prince, he was sent to prison instead.

The Shah ordered pro-British

The Shah ordered pro-British Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Ali Mansur

Ali Khan Mansur ( fa, علی خان منصور, also known as ''Mansur ul-Mulk'' (); 1886 – 8 December 1974) was the Prime Minister of Iran for two terms between 1940 and 1941 and in 1950.

Biography

Born in Tehran, he served as Govern ...

, whom he blamed for demoralising the military, to resign, replacing him with former prime minister Mohammad Ali Foroughi

Mohammad Ali Foroughi ( fa, محمدعلی فروغی; early August 1877 – 26 or 27 November 1942), also known as Zoka-ol-Molk ( Persian: ذُکاءُالمُلک), was a writer, diplomat and politician who served three terms as Prime Mini ...

.